1. Introduction

Buildings account for a significant share of global energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, accounting for roughly 40% of total energy use and associated emissions in advanced economies [

1]. In the European Union, the residential sector alone accounts for a substantial share of final energy demand, driven by heating, cooling, lighting, and appliance loads [

2]. In Cyprus, residential buildings account for over 30% of national energy consumption, and this figure is expected to rise without targeted interventions to increase energy efficiency and integrate renewable energy sources (RESs) [

2]. Consequently, enhancing the energy performance of residential buildings has become a central objective of contemporary sustainable development strategies, both to mitigate climate change and to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels.

The dependence on conventional energy sources for electricity and heat generation not only contributes to elevated GHG emissions but also exposes households to volatile energy prices and security risks. Cyprus’s insulated electricity grid and heavy reliance on imported fuels underscore the urgency of transitioning to locally available renewable energy solutions, especially given the island’s high solar irradiation levels and Mediterranean climate [

3]. The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its recent revisions reinforce this imperative by mandating zero-emission standards for new buildings and requiring Member States to support solar readiness and RES deployment in the building sector by 2030 [

4]. These policy shifts reflect broader EU goals to decarbonize residential energy use and to promote nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEBs) as benchmarks for future construction and retrofit efforts.

Among RESs, solar energy technologies—including photovoltaic (PV) and solar thermal systems—have emerged as particularly promising for residential applications due to their scalability and compatibility with existing building forms. In Cyprus, solar thermal systems for domestic hot water production have achieved widespread penetration, with installation rates exceeding 90% of dwellings, mainly owing to favorable climatic conditions and supportive policy frameworks [

5]; this prevalence has enabled the island to exceed EU targets for renewable heating and cooling in buildings [

6]. Despite this success, rooftop PV solar electricity generation remains underutilized relative to its potential, suggesting that further integration of solar systems could yield significant gains in energy performance and emissions reductions.

Energy performance research globally has increasingly focused on integrating renewable energy technologies (RETs) with advanced control systems to achieve sustainable, high-performance building outcomes. Recent reviews highlight that integrating PVs with efficient energy management systems and building energy management systems (BEMS) can substantially improve building energy performance and occupant comfort while reducing operational emissions [

2,

3,

7]. For instance, hybrid energy systems combining PV arrays, solar thermal collectors, and smart IoT-based controls have demonstrated significant improvements in energy efficiency and load balancing compared with conventional configurations [

8]. Moreover, the deployment of BEMS and smart readiness indicators has been linked to more adaptive, responsive control of HVAC, lighting, and energy storage systems, thereby further enhancing energy performance under variable environmental conditions [

9].

Despite these advances, there remains a clear need for context-specific research examining the performance of solar RESs and smart technologies within Cyprus’s unique climatic, architectural, and regulatory environment. While the impacts of renewable energy systems and building energy management systems on building energy demand have been examined in previous studies, the results presented here should be understood as a complementary, context-specific contribution that extends existing knowledge through a typology-based, climate-responsive assessment for Cyprus.

Furthermore, existing studies of Mediterranean residential buildings have shown that integration of building-applied photovoltaics (BAPV) or building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) can materially improve energy balance and reduce net energy demand when appropriately configured with building orientation and typology [

10]. However, research specifically assessing real-world combinations of solar systems and digitalized energy management strategies in Cyprus is limited. Compounding this gap are findings that Cyprus’s official energy performance simulation standards—such as iSBEM-Cy—may significantly misestimate actual energy consumption, particularly for cooling loads, highlighting the need for more empirical and simulation-based studies to align modeled performance with lived outcomes [

5,

6,

10].

Smart building technologies, encompassing sensors, automation, and IoT-enabled controls, offer additional pathways to improve energy performance by optimizing energy flows, predicting consumption patterns, and enabling demand-side management. A growing body of literature suggests that advanced control systems improve energy efficiency by enabling real-time responses to environmental and occupancy changes, reducing waste, and enhancing the integration of intermittent RESs, such as solar PV [

10]. The Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI) framework, recently developed within the EU, underscores the importance of digital readiness in supporting adaptive energy management features that complement the deployment of renewable technologies [

11]. However, the combined impact of solar RESs and smart building technologies on energy performance—especially in existing residential buildings with diverse construction eras, orientations, and occupancy patterns—remains underexplored.

In Cyprus, although solar thermal solutions have historically dominated renewable energy penetration, there is growing attention to solar PV and smart technologies as means to further decarbonize residential energy use. Empirical assessments in Northern Cyprus, for example, have examined the performance and initial investment costs of solar domestic hot water (SDHW) systems, indicating favorable outcomes for renewable integration when economic variables are considered [

9,

10,

11]. However, comprehensive studies that simultaneously evaluate the potential of solar PV generation, smart energy management interventions, and their combined effects on overall energy performance are scarce. This gap is particularly salient given the Mediterranean climate’s influence on both energy demand and solar resource availability.

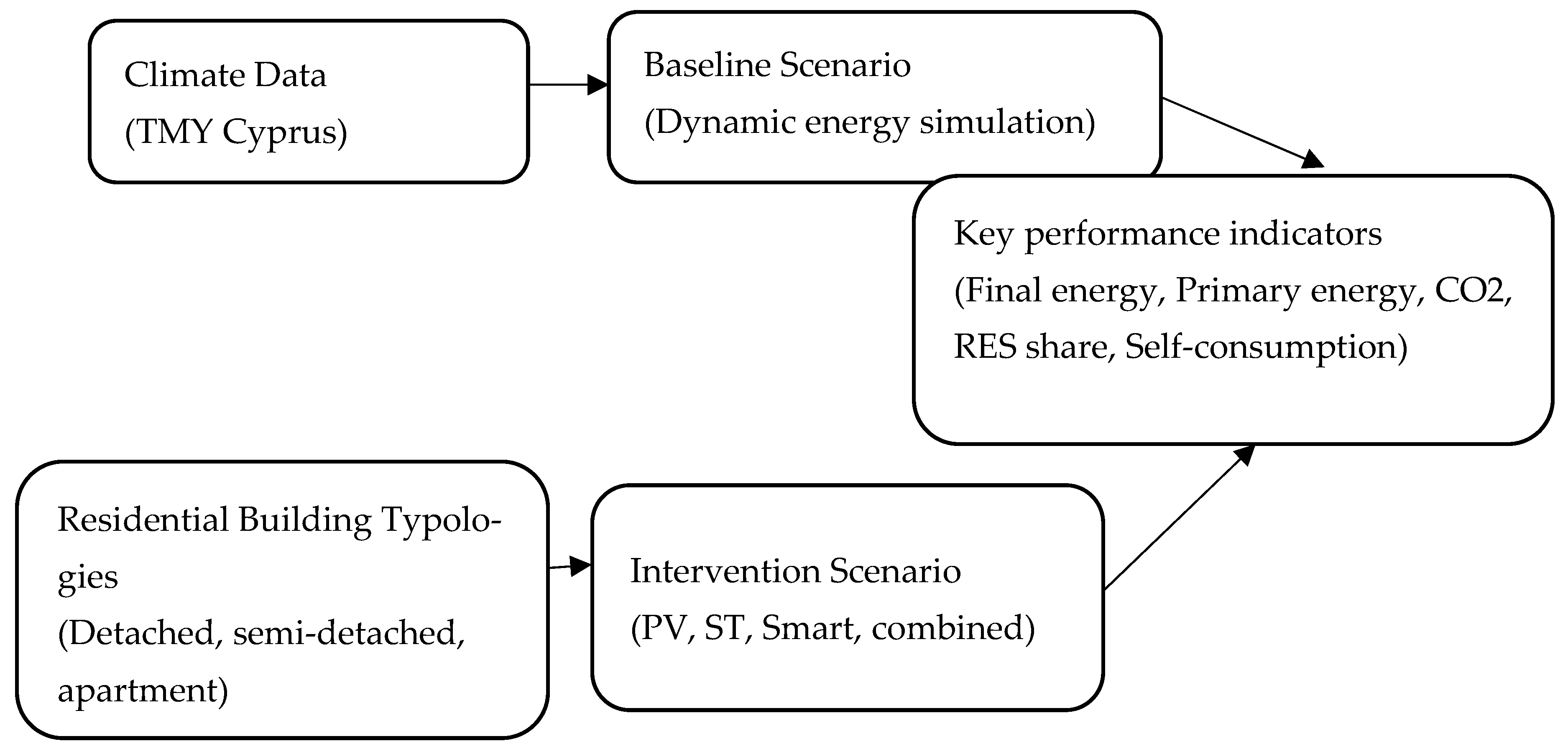

The present study addresses these gaps by systematically evaluating how solar renewable energy systems and smart building technologies can improve the energy performance of residential buildings in Cyprus. Through a combination of energy performance simulation, scenario modeling, and analysis of policy and technical barriers, this research aims to quantify the impacts of on-site solar systems augmented by digital control strategies on key performance indicators, including primary energy consumption, peak load reduction, and GHG emissions. By focusing on typical residential typologies in Cyprus and leveraging recent policy directives and technological advances, the study contributes to both scholarly understanding and practical guidance for advancing sustainable residential energy practices in Mediterranean climates. The research framework is presented in

Figure 1.

5. Results

Table 2 presents the baseline annual energy performance indicators for the three representative residential building typologies examined in this study, prior to the introduction of solar renewable energy systems or smart building technologies. Results are reported using both absolute values (kWh/year, kg/year) and normalized intensity indicators (per m

2) to enable meaningful comparison across building types of different sizes, in line with the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD).

The primary energy demand was calculated using Cyprus-specific primary energy factors for electricity, while CO2 emissions were derived using the national electricity emission factor (0.72 kg CO2/kWh). Although detached houses exhibit the highest absolute energy consumption due to larger floor areas, apartment units display the highest energy and emissions intensity per square meter, reflecting lower envelope performance and greater reliance on cooling. These baseline results confirm the cooling-dominated energy profile of the Cypriot residential sector and provide the reference case against which all solar, smart, and combined intervention scenarios are evaluated in subsequent sections.

Table 3 disaggregates the baseline final energy consumption presented in

Table 1 into its principal end-use components: cooling, space heating, domestic hot water (DHW), lighting, and appliances. This breakdown is derived from the dynamic energy simulations and reflects typical occupancy schedules, internal gains, and system efficiencies for residential buildings in Cyprus. The results clearly demonstrate that cooling constitutes the dominant end-use energy demand across all residential typologies, accounting for approximately 44–48% of total final energy consumption. This finding explains why photovoltaic (PV) electricity generation delivers greater performance benefits than solar thermal systems in subsequent scenarios and underscores the importance of electricity-based renewable solutions in cooling-dominated Mediterranean climates. Space heating and DHW account for smaller shares of total demand due to Cyprus’s mild winter conditions and widespread use of solar thermal systems for hot water. Lighting and appliance loads remain non-negligible, particularly in detached houses, reinforcing the role of smart building technologies in optimizing electricity use and enhancing photovoltaic self-consumption.

Table 4 summarizes the effect of solar renewable energy systems—PV, solar thermal (ST), and combined PV + ST—on energy performance indicators. Solar PV systems (EnergyIntel Group, Nicosia) achieve greater primary energy and CO

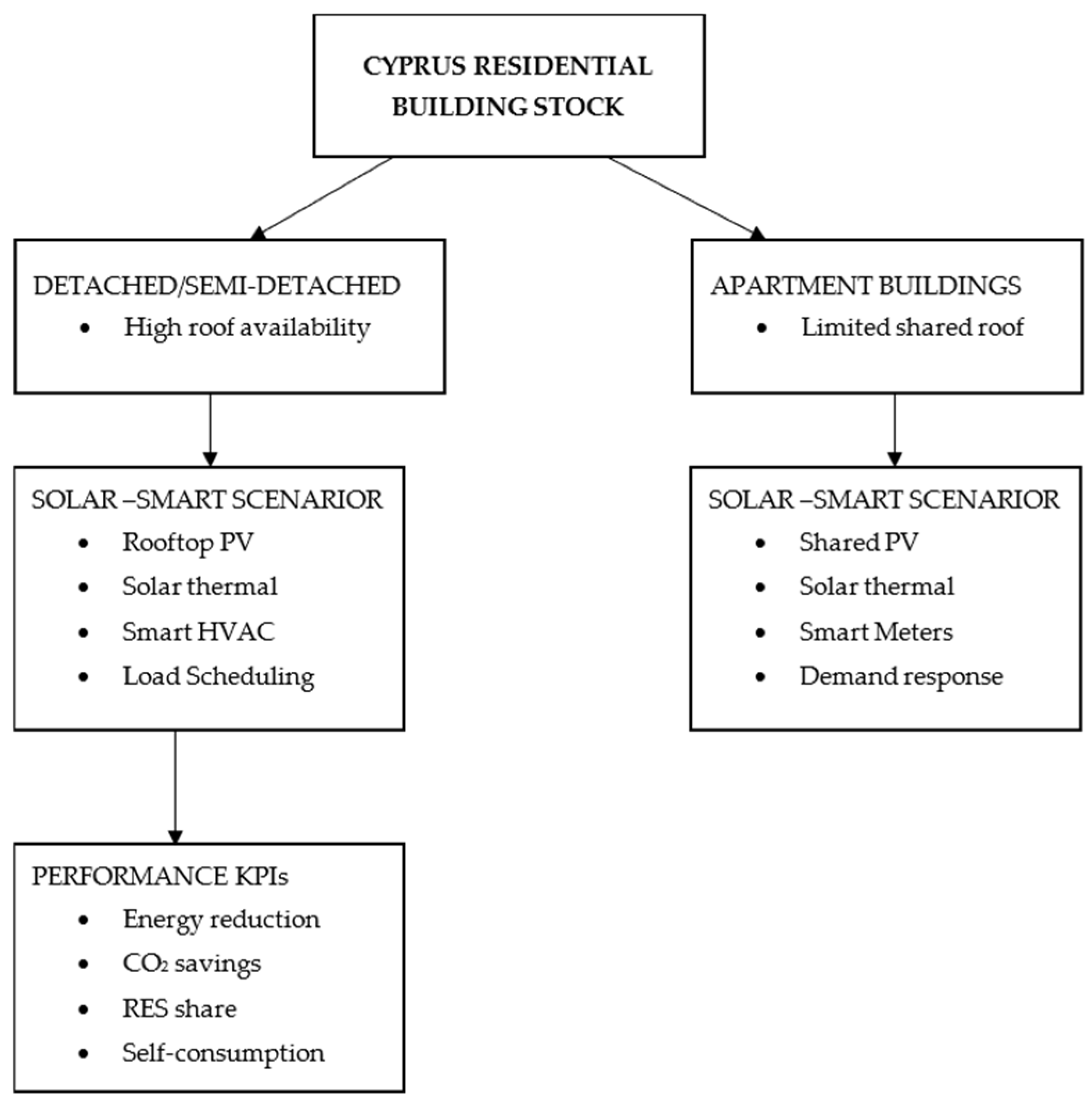

2 reductions than solar thermal systems across all typologies, reflecting the electricity-intensive cooling demand in Cyprus. Solar thermal systems contribute more modestly, primarily by offsetting domestic hot water loads. The combined PV + ST scenario consistently delivers the highest performance gains, achieving up to 45% reduction in primary energy in detached houses.

Apartment buildings demonstrate lower absolute gains due to limited roof availability, confirming the structural constraints identified in the literature. These results demonstrate that solar systems—especially PV—are highly effective in improving residential energy performance in Cyprus.

Table 5 presents the performance improvements achieved solely through smart building technologies. Smart technologies deliver moderate but consistent reductions in energy consumption, primarily by optimizing HVAC operation and enabling load shifting. Notably, peak load reductions are substantial, reaching up to 28% in apartment units, which is particularly relevant given Cyprus’s summer grid stress conditions. Although smart systems alone do not achieve the deep decarbonization levels observed with solar RESs, they significantly enhance operational efficiency. These findings directly confirm the added value of smart technologies in optimizing residential energy use.

The integrated effect of solar RESs and smart technologies is shown in

Table 6. The combined scenarios outperform all individual interventions, confirming a synergistic effect between solar generation and smart control. Smart technologies increase PV self-consumption by 25–30 percentage points, reducing grid exports and improving system efficiency. Detached and semi-detached houses approach nearly zero-energy performance, while apartment buildings achieve meaningful but constrained improvements. These results demonstrate that integrated solar–smart systems are the most effective strategy for enhancing energy performance.

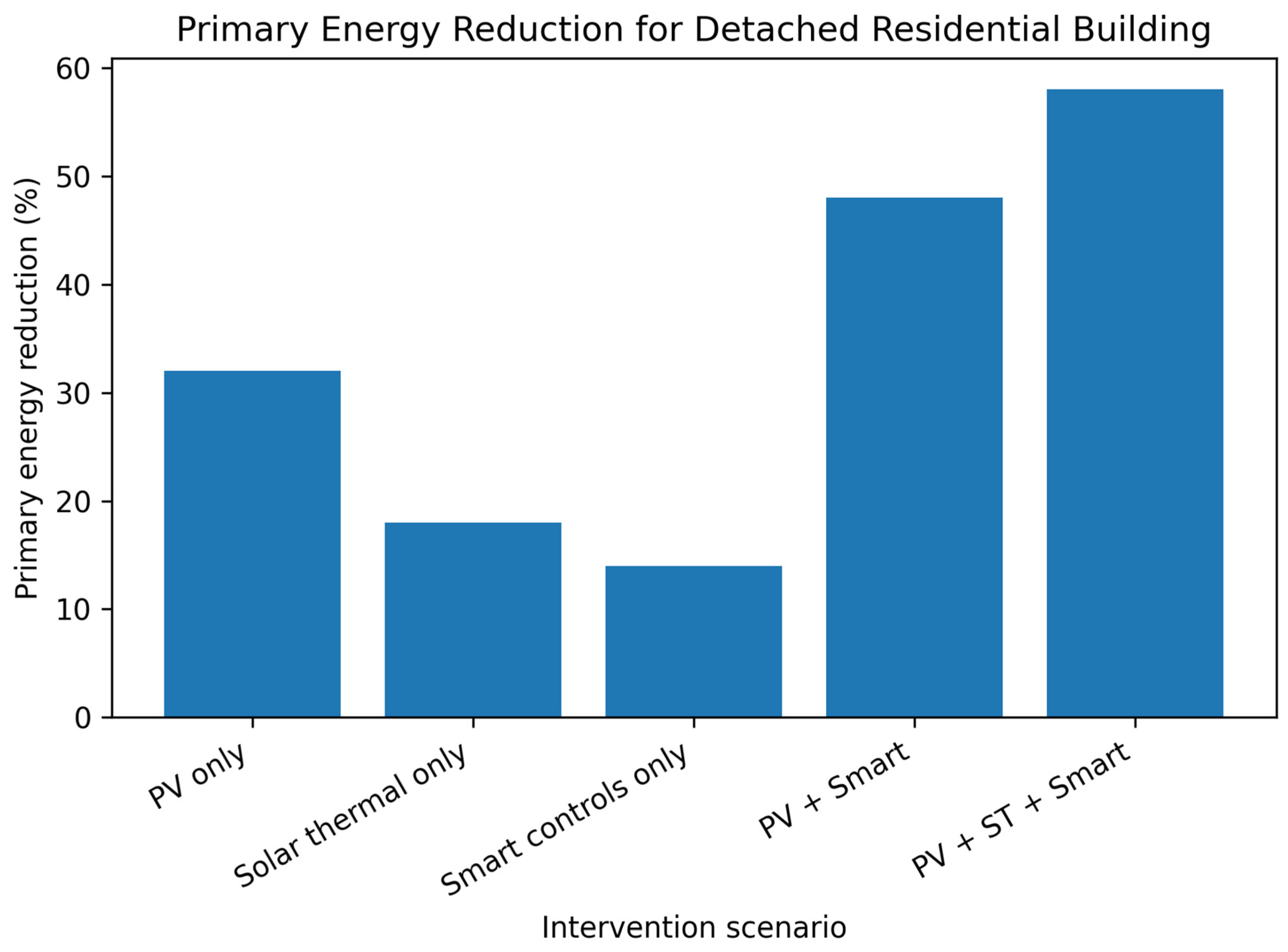

Figure 3 compares standalone and integrated solar-smart technology scenarios, highlighting the superior performance of combined solar–smart configurations.

Figure 3 reinforces the quantitative findings, clearly showing that integrated interventions deliver the highest performance gains, while single-measure approaches yield diminishing returns. Altogether, baseline residential buildings in Cyprus exhibit high cooling-driven energy demand. Solar PV systems provide the most considerable standalone energy and emissions reductions. Smart building technologies significantly reduce peak loads and enhance operational efficiency. Combined solar–smart systems deliver the highest energy performance improvements, achieving up to 58% reduction in primary energy. Building typology strongly influences achievable performance, highlighting the need for differentiated strategies. Collectively, these results provide robust evidence for integrating solar renewable energy systems and smart building technologies as a cornerstone for improving residential energy performance in Cyprus.

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpreting Energy Performance Enhancement in the Cypriot Context

The results demonstrate that significant improvements in residential energy performance in Cyprus are achievable through the combined deployment of solar renewable energy systems and smart building technologies. The observed reductions in primary energy demand (up to 58%) and CO

2 emissions (up to 55%) place integrated solar–smart configurations within the performance range associated with nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEBs), corroborating findings from Mediterranean and Southern European studies [

13,

24]. However, the magnitude of improvement achieved in this study exceeds that reported in several previous works that examined renewable or smart interventions in isolation [

18,

20].

These findings reinforce the theoretical position that energy performance enhancement is a systemic outcome, rather than the result of individual technological measures. As argued in the literature on integrated building systems, renewable energy technologies realize their full potential only when aligned with adaptive control strategies and occupant-responsive operation [

21,

25]. In the Cypriot context, where cooling demand dominates and solar availability is high, this alignment proves particularly effective.

At the same time, the differential performance across building typologies highlights the importance of contextual specificity, a theme emphasized in recent critiques of universal NZEB models [

23]. While detached and semi-detached houses approach near-zero energy performance, apartment buildings remain structurally constrained by limited roof access and fragmented ownership. This finding confirms earlier research that identified multi-owner residential buildings as a critical bottleneck to large-scale decarbonization [

34].

6.2. Policy Implications: From Technology Deployment to System Integration

From a policy perspective, the results underscore the need to move beyond technology-specific incentives toward integrated policy frameworks that explicitly encourage the coupling of renewable energy systems with smart building technologies. While Cyprus has successfully promoted solar thermal adoption and increasingly supports rooftop PV deployment [

30,

37], current policy instruments do not sufficiently address demand-side management, smart readiness, and self-consumption optimization.

The strong performance of combined solar–smart scenarios suggests that future revisions of national building regulations and subsidy schemes should prioritize system-level performance metrics, such as primary energy reduction and PV self-consumption ratios, rather than installed capacity alone. This aligns with recent developments in the EPBD and the introduction of the Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI), which recognizes digitalization as a core component of building energy performance [

4].

Moreover, the pronounced peak load reductions achieved through smart technologies have implications for Cyprus’s isolated electricity system. By mitigating summer peak demand, smart-enabled residential buildings can help stabilize the grid and reduce the need for costly infrastructure upgrades. Policymakers could leverage this potential by integrating residential demand-response mechanisms into national energy planning and by accelerating the rollout of smart meters [

38].

From a green building certification perspective, the findings of this study align most closely with LEED v4.1 Energy & Atmosphere (EA) credits, particularly those related to optimized energy performance, on-site renewable energy generation, and operational energy efficiency. The emphasis on integrated solar photovoltaic systems and smart energy management strategies aligns with LEED’s growing focus on measured and operational performance rather than prescriptive design measures.

By contrast, the relevance of the present analysis to Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) and Materials and Resources credits is inherently more limited, as these categories depend primarily on indoor comfort parameters, material selection, embodied impacts, and construction practices, which are beyond the scope of this energy-focused assessment. Nevertheless, smart HVAC control strategies may indirectly support IEQ objectives by improving thermal comfort stability and reducing overheating risks, particularly in cooling-dominated Mediterranean climates. Future research integrating indoor comfort metrics and life-cycle material assessments would be needed to address these LEED credit categories explicitly.

6.3. Indicative Economic Performance

To complement the energy and emissions analysis, an indicative economic assessment was carried out to contextualize the financial implications of the evaluated solar–smart configurations. Although a complete life-cycle cost analysis is beyond the scope of this study, representative capital costs were estimated using typical residential market values in Cyprus, consistent with recent national reports and installer price ranges.

For solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, installed costs were assumed to range between 1200 and 1400 €/kWp, reflecting current turnkey prices for small-scale residential installations. Solar thermal systems for domestic hot water preparation were assumed to cost 700–900 € per system, in line with widely adopted flat-plate collector solutions. Smart building technologies, including smart thermostats, basic energy monitoring systems, and automated load control devices, were estimated at 800–1200 € per dwelling, depending on system complexity and level of automation.

Based on these cost assumptions and the simulated energy savings, simple payback periods were estimated for the main intervention configurations. Standalone PV systems achieve payback periods of approximately 7–9 years, primarily driven by reductions in grid electricity consumption. When PV systems are combined with smart control technologies, payback periods are reduced to 6–8 years, reflecting enhanced photovoltaic self-consumption and improved load matching. Fully integrated configurations combining PV, solar thermal systems, and smart controls exhibit slightly more extended payback periods of 7–10 years, due to higher upfront investment costs, despite delivering the highest overall energy and emissions reductions.

These indicative results suggest that integrated solar–smart solutions are not only technically effective but also economically viable under current Cypriot conditions, particularly when smart technologies are used to enhance photovoltaic performance. The findings reinforce the importance of assessing renewable energy systems and digital control technologies as integrated investments, rather than as isolated measures, especially in cooling-dominated Mediterranean climates.

While the present study primarily focuses on operational energy consumption and associated CO2 emissions, it is important to acknowledge the life-cycle environmental implications of the proposed solar–smart systems. In residential buildings, operational emissions typically dominate total life-cycle impacts, particularly in electricity-intensive and cooling-dominated climates such as Cyprus. Existing life-cycle assessments of solar photovoltaic systems indicate that their embodied greenhouse gas emissions are generally offset within the first few years of operation, after which net environmental benefits accumulate over the system lifetime. Similarly, smart building technologies are characterized by relatively low material intensity and short energy payback periods, given the operational energy savings they enable.

Although embodied impacts related to photovoltaic modules, inverters, and control hardware are not explicitly quantified in this study, available evidence suggests that the operational CO2 reductions identified here significantly outweigh the embodied emissions over typical system lifetimes. A comprehensive life-cycle assessment integrating embodied energy, material flows, and end-of-life considerations would further strengthen the environmental evaluation and is recommended as a priority for future research.

6.4. Economic Implications: Cost-Effectiveness and Investment Priorities

Although this study does not conduct a complete life-cycle cost analysis, the results offer important insights into the economic logic of energy performance enhancement. Solar PV systems deliver higher primary energy and emissions reductions than solar thermal systems, suggesting that investment priorities may need to be recalibrated in cooling-dominated climates such as Cyprus. This finding contrasts with earlier Cypriot studies that emphasized solar thermal systems primarily on the basis of short payback periods [

9], suggesting a shift in optimal strategies as electricity demand grows.

The role of smart technologies further complicates traditional cost–benefit assessments. While smart systems yield smaller standalone energy savings compared to solar RESs, their capacity to enhance PV self-consumption and reduce peak loads significantly improves the overall economic performance of integrated systems. These synergistic benefits are often underestimated in conventional economic evaluations, which tend to assess technologies in isolation [

26].

For apartment buildings, the lower performance gains highlight the need for collective investment models, such as renewable energy communities (RECs) and shared PV systems. Without such mechanisms, economic barriers related to scale, ownership, and governance are likely to persist, limiting the diffusion of high-performance solutions in dense urban areas.

6.5. Design Implications: Rethinking Residential Architecture and Retrofit Strategies

The findings carry important implications for architectural and engineering design practice in Cyprus. First, the strong influence of roof availability on energy performance outcomes underscores the need to treat solar integration as a design determinant, rather than a post-design add-on. New residential developments should prioritize roof orientation, shading control, and structural readiness for PV and solar thermal systems, consistent with emerging green architecture principles [

8].

Second, the effectiveness of innovative building technologies in reducing peak loads and improving self-consumption suggests that design for flexibility and adaptability is increasingly critical. This includes provisions for sensor integration, control infrastructure, and future upgrades, particularly in retrofit projects where physical constraints are more pronounced.

Finally, the results challenge purely performance-driven design paradigms by highlighting the role of occupant interaction and behavioral adaptation. Smart systems function most effectively when residents are engaged and informed, underscoring the need for participatory, user-centered design approaches. This aligns with broader theoretical arguments that energy-efficient buildings are socio-technical systems shaped as much by human practices as by technological configurations [

21].

6.6. Positioning the Study Within Current Research and Practice

By demonstrating the superior performance of integrated solar–smart solutions under Cyprus-specific conditions, this study contributes to a growing body of literature advocating for holistic, context-sensitive energy performance strategies. It extends previous research by quantitatively linking renewable generation, intelligent control, and building typology within a single analytical framework, addressing gaps identified in both Mediterranean and island energy studies [

23,

39].

Notably, the findings caution against uncritically transferring building energy models across climatic and regulatory contexts. Instead, they support an approach to residential energy performance enhancement that is technically integrated, policy-aligned, economically informed, and design-driven. In doing so, the study provides actionable insights for policymakers, designers, and energy planners seeking to advance sustainable residential development in Cyprus and comparable Mediterranean regions.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the potential for improving the energy performance of residential buildings in Cyprus through the integrated application of solar renewable energy systems and smart building technologies. By combining typology-based modeling, performance indicators, and scenario analysis, the research provided a comprehensive assessment of how different residential forms respond to renewable and digital interventions under Mediterranean climatic conditions.

The results demonstrate that Cyprus’s residential building stock holds substantial untapped potential for energy performance enhancement. Baseline analysis confirmed that cooling-driven electricity demand remains the dominant contributor to primary energy use and carbon emissions. Solar photovoltaic systems emerged as the most effective standalone renewable technology, achieving significantly higher energy and emissions reductions than solar thermal systems. Smart building technologies, while producing more moderate reductions in final energy demand, proved particularly effective in lowering peak loads and increasing photovoltaic self-consumption. Most importantly, the integrated deployment of solar and smart systems yielded synergistic effects, enabling primary energy reductions of up to 58% and CO2 reductions of up to 55%, approaching near-zero energy performance for low-rise residential typologies.

These findings confirm that energy performance enhancement in residential buildings is inherently systemic, requiring coordinated technological, regulatory, and design interventions rather than isolated measures. The study contributes empirical evidence to ongoing debates on the role of digitalization in building decarbonization and provides a climate-specific reference for Mediterranean and island contexts.

7.1. Implications

Based on the results, several policy-oriented recommendations emerge. National support schemes should move beyond isolated subsidies for solar technologies and explicitly encourage integrated solar–smart solutions. Incentive structures that reward performance outcomes—such as primary energy reduction, self-consumption rates, and peak load mitigation—would better align with system-level decarbonization goals.

The incorporation of smart readiness requirements into national building codes, aligned with the EU Smart Readiness Indicator framework, would accelerate the adoption of digital energy management systems and enhance the effectiveness of renewable energy integration. Apartment buildings face structural and ownership-related constraints that limit the deployment of renewable energy. Policies facilitating renewable energy communities, shared PV systems, and collective self-consumption models are essential to ensure equitable access to high-performance solutions. The demonstrated peak load reductions highlight the potential of smart residential buildings to support grid stability. Policymakers should integrate residential demand-response mechanisms into national energy strategies, particularly as electrification increases.

While this study provides a robust analytical foundation, several avenues for future research remain. Future studies should incorporate detailed life-cycle cost analyses, including capital costs, operational savings, and payback periods, to strengthen the economic case for integrated solar–smart systems. Empirical research on occupant engagement with smart technologies would improve understanding of behavioral influences on energy performance and inform user-centered design strategies. Extending the analysis from individual buildings to neighborhood and district scales would enable assessment of collective energy strategies, grid interactions, and renewable energy communities. Further work should explore how integrated systems influence indoor comfort and resilience under future climate scenarios, particularly during extreme heat events.

7.2. Limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, the results are based on modeled scenarios and representative building typologies, which, while grounded in national data, may not capture the full variability of the existing residential stock. Second, economic indicators were not explicitly quantified, limiting direct assessment of financial feasibility. Results are based on modeled scenarios using representative typologies. Occupant behavior was assumed to be semi-static, though a sensitivity analysis confirms its influence on cooling demand. Empirical validation through monitored case studies is recommended for future research. Addressing these limitations through empirical monitoring and longitudinal studies would further strengthen the evidence base.

The results presented in this study are derived from dynamic energy simulation scenarios and therefore represent modeled estimates of energy and emissions performance under defined assumptions. While simulation-based approaches are widely used to evaluate building-scale energy interventions, empirical validation through field measurements, monitored case studies, or long-term operational data would further strengthen confidence in the magnitude of predicted savings. In the Cypriot context, such empirical datasets remain limited, particularly for integrated solar–smart residential systems. Future research should therefore focus on combining simulation with post-occupancy monitoring and real-world performance evaluation to validate and refine the findings presented here.

This research demonstrates that integrating solar renewable energy systems and smart building technologies offers a technically robust, policy-relevant, and design-informed pathway to improve the energy performance of residential buildings in Cyprus. The findings support a transition toward holistic, system-oriented approaches to building decarbonization that are adaptable to Mediterranean climates and transferable to similar regional contexts.