1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has established ambitious goals under its sustainability agenda, such as achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 and transitioning to a circular economy. Within this context, the concept of zero-waste manufacturing emerges as a key enabler, aiming to minimize waste, reduce defects, and enhance resource efficiency across production processes [

1]. Thus, sustainable manufacturing practices have become a key enabler to enhance operational efficiency while mitigating the environmental impacts of industries. Focusing in detail on zero-waste manufacturing (ZWM), this concept was created to support countries’ transition to a circular economy by developing manufacturing technologies and systems that eliminate waste through the entire manufacturing process [

2]. Among the different industries, the composites sector, characterized by its resource-intensive processes and high environmental impact, faces unique challenges in aligning with these goals [

3]. Composite manufacturing involves significant material waste and energy consumption, as well as end-of-life management issues, which limit recycling and reuse capacity [

4]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for tools that assess both process efficiency and eco-efficiency, enabling industries to identify opportunities for improvement while supporting decision-making aligned with EU sustainability targets [

5]. Achieving these objectives requires improving operational efficiency but also addressing environmental sustainability through integrated assessment methodologies. In this context, eco-efficiency emerges as a critical framework, since it integrates economic and environmental performance indicators to evaluate the sustainability of manufacturing processes. This assessment will enable the identification of processes that require improvement actions, supporting informed decision-making regarding the selection of the most suitable technologies or approaches to implement on the shop floor. By prioritizing improvement actions, risks and high investment costs are mitigated, allowing for focusing on process steps that will enhance the overall performance, resource efficiency, and waste reduction.

Studies on efficiency and eco-efficiency assessment have been widely explored to optimize industrial processes and minimize environmental impact. While efficiency assessment focuses on evaluating resource utilization, energy consumption, and productivity to improve operational performance [

6], eco-efficiency assessment expands the scope by integrating environmental performance into traditional efficiency metrics [

7]. This approach was globally promoted by the World Business for Sustainable Development in 1991 by declaring that “eco-efficiency is achieved through the delivery of competitively priced goods and services that satisfy human needs and bring quality of life while progressively reducing environmental impacts of goods and resource intensity throughout the entire life-cycle to a level at least in line with the Earth’s estimated carrying capacity” [

8]. In a more mathematical language, eco-efficiency evaluates the ratio of economic value generated to environmental impact caused, promoting practices that align with sustainable development goals [

9]. Tools such as Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Material Flow Analysis (MFA) are frequently applied for this purpose, enabling industries to measure their environmental performance and identify areas for improvement [

10]. In recent years, hybrid models combining efficiency and environmental impacts have gained attention for their holistic approach to process evaluation. For example, Lean–Green Manufacturing integrates lean principles with eco-efficiency metrics to simultaneously address economic and environmental challenges [

11]. Recently, ref. [

12] proposed an efficiency framework based on a holistic approach, which combines different assessment methods and tools to support improvement on a continuous basis and increase eco-competitiveness.

Table 1 summarizes key frameworks identified in the literature, combining Value Stream Mapping (VSM), Water Scarcity Footprint (WSF) analysis, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), Life-Cycle Cost (LCC) and LCA, and Multi-layer Stream Mapping (MSM). An industrial use case application linked to each framework is also mentioned to highlight the applicability of these models.

Although the reviewed methodologies, presented in

Table 1, enable the calculation of eco-efficiency, using specific variables that allow to estimate both process efficiency and environmental impact, they present limitations in terms of flexibility and scalability. For example, LCA is highly effective in identifying manufacturing processes that generate a high quantity of waste. However, if not complemented by a careful analysis of the process, it becomes difficult to identify the root causes of inefficiencies and to implement actions or integrate methods and technologies to eliminate them. To promote the scalability of the efficiency and eco-efficiency assessment, it is important to provide the industry with intuitive tools that support their decision-making process, and this starts with a correct characterization of the process steps and sub-steps. Moreover, it is important to consider multiple streams such as time, energy, materials, and consumables and, at each step, analyze the variables that “add value” to the process. This detailed characterization will allow detection of different forms of waste and inefficiencies contributing to the ZDM.

In this context, this work introduces a methodology that integrates Multi-layer Stream Mapping (MSM) concepts, cited by [

11,

19,

20], with Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI) analysis. By combining these two approaches, the proposed method is implemented in order to identify inefficiencies across multiple stages of composite manufacturing processes, enhancing process transparency and resource tracking, and supporting the strategic decision-making of the companies toward zero-waste. The methodology was designed to be straightforward, highly flexible, and adaptable, allowing its implementation across different industrial sectors and assessing several manufacturing processes based on real operational data. By guiding companies through a detailed analysis that considers the real characteristics of the process, variables can be accurately identified and monitored, supporting the implementation of solutions in specific process steps that allow achievement of ZDM goals.

This study is integrated into the FLASHCOMP EU project, whose main objective consists of developing a fast and reliable quality control solution that uses artificial intelligence to help identify and remove defects during composite manufacturing processes, reducing waste and increasing process performance. To identify the most critical process steps and enable the efficient implementation of targeted solutions, a comprehensive baseline assessment will be conducted for two industrial use cases from the aerospace and shipbuilding sectors. This study allows the assessment of the current state of their production processes and characterizes process performance across environmental, economic, and operational domains. The process steps were selected due to their critical role in resource utilization, labor intensity, and environmental impact. By analyzing process workflows, cost structure, and environmental impacts, inefficiencies, such as excessive non-value-added activities and high material waste, can be identified.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the methods applied to conduct the study,

Section 3 shows and discusses the main results obtained for the two use cases;

Section 4 focuses on the main lessons learned from the implementation of the present framework; and finally,

Section 5 concludes by highlighting the relevance of the work in contributing to zero-waste practices in composite manufacturing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Studies

The case studies of this work have been conducted in two industrial companies, one from the aerospace sector and another from the shipbuilding sector.

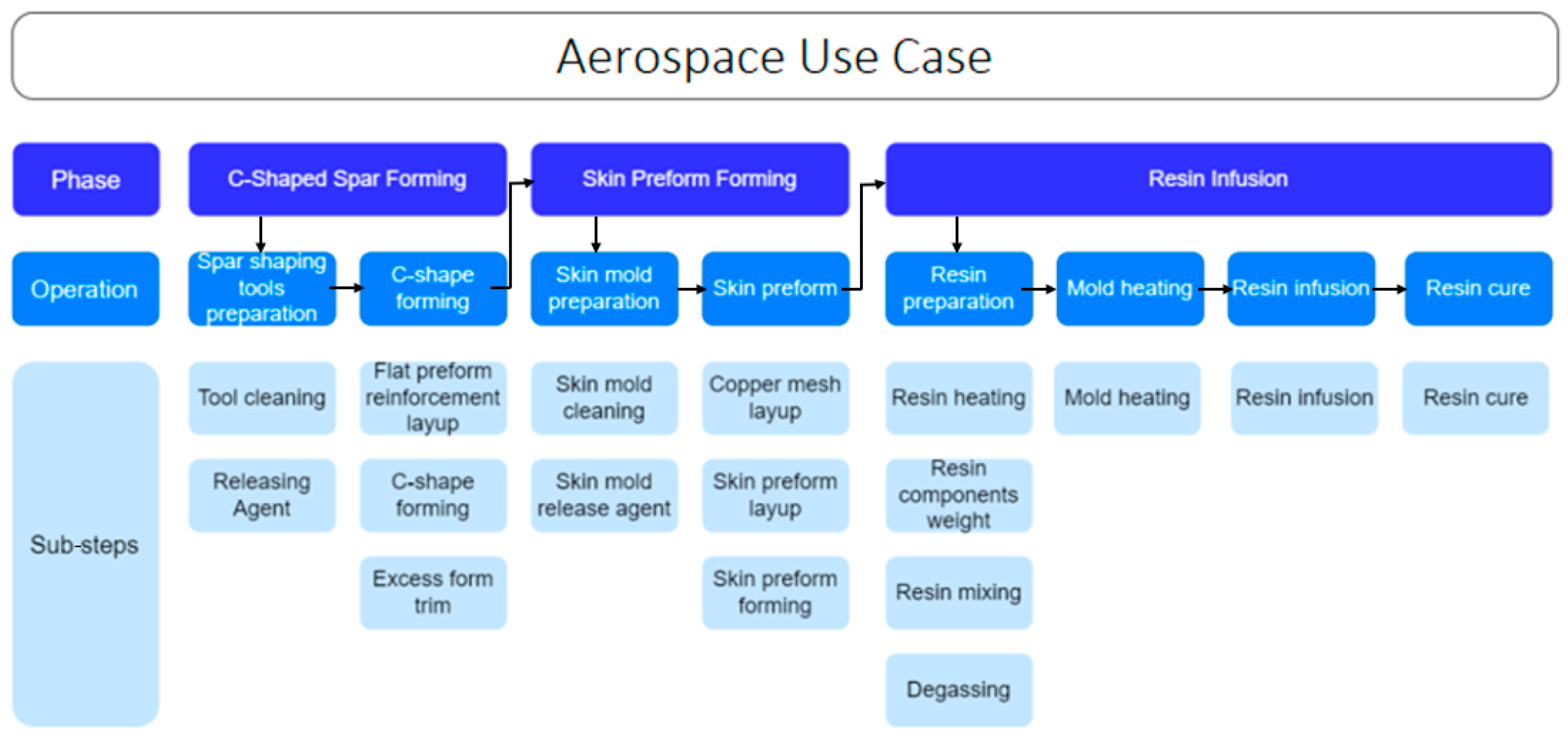

Use case from the aerospace sector: This use case is a prominent player in the aerospace sector, specializing in the development and production of advanced systems for both defense and commercial applications. The company operates in a highly regulated and competitive environment, where precision, quality, and operational efficiency are critical to maintaining industry leadership. Within its manufacturing processes, depicted in

Figure 1, the company employs cutting-edge techniques to ensure the production of high-performance components that meet stringent industry standards.

To optimize its production flow and align with sustainability goals, the use case selected critical phases of its manufacturing process for in-depth analysis and baseline formulation. The focus was placed on the following process phases:

C-shaped-spar forming—This phase involves shaping composite materials into specific structural components, requiring precise execution to ensure the integrity and performance of the final product;

Skin preform forming—In this phase, preformed composite materials are shaped and prepared for integration, demanding careful handling to avoid defects or misalignments that could compromise quality;

Resin infusion—This phase entails the infusion of resin into composite structures, ensuring proper bonding and structural integrity. It is a time-sensitive and material-intensive operation, critical for achieving desired mechanical properties.

Each phase comprises a series of operations that can be further divided into sub-steps. This multi-level analysis enables the identification of inefficiencies within specific process phases, facilitating targeted interventions and reducing the likelihood of errors.

The analysis of these phases was focused on the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) which were selected by resin infusion experts and validated by the company. Particular attention was given to identifying NVA activities and exploring opportunities for process improvement. Additionally, the integration of sensor-based monitoring during the project is expected to enhance process control and reduce inefficiencies, contributing to a more sustainable and streamlined production system.

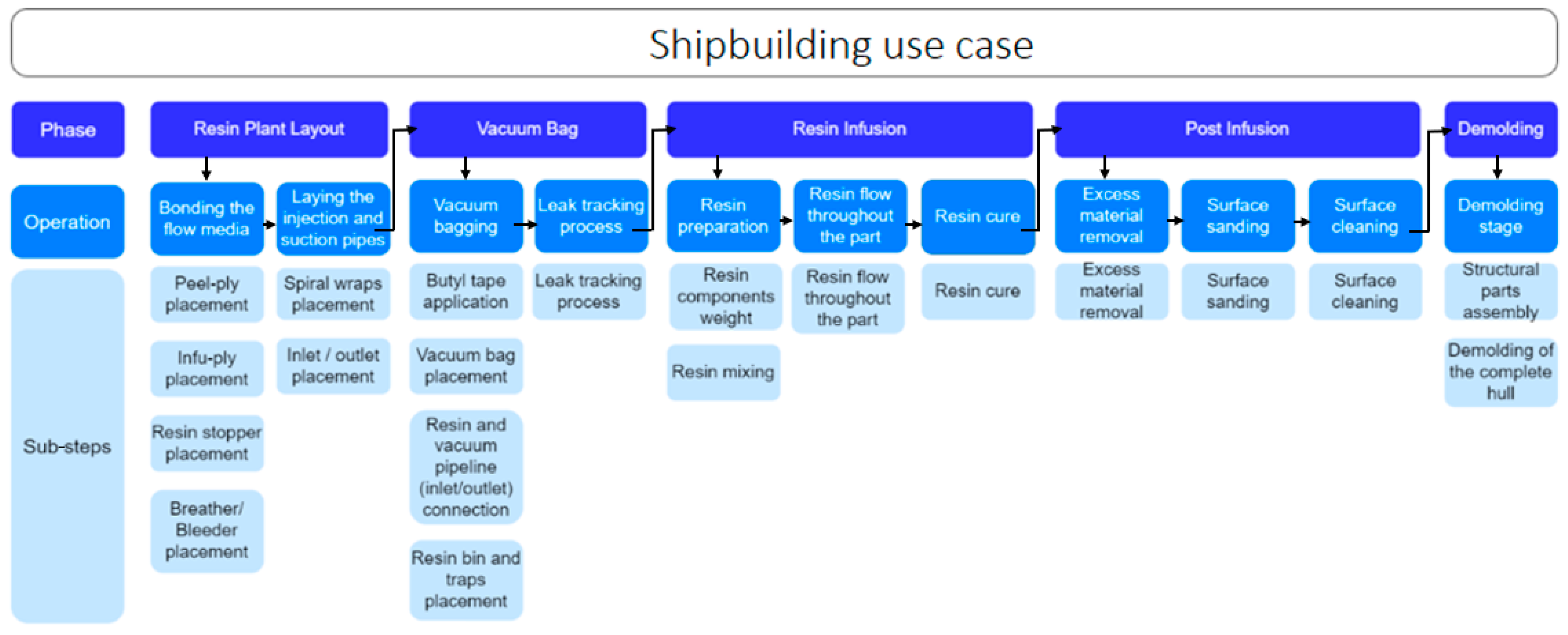

Shipbuilding use case: This use case is a leading manufacturer in the luxury boat industry, renowned for its innovative designs, craftsmanship, and technological advancements. Operating in a competitive market where aesthetics, durability, and sustainability are key factors, the company consistently invests in improving its manufacturing processes to maintain its reputation for excellence.

To enhance its production efficiency and align with sustainability objectives, the use case identified key phases in its manufacturing process for detailed analysis and baseline formulation. The focus was placed on the following process phases, depicted in

Figure 2:

Resin plant layout—This phase involves preparing the resin distribution system to ensure accurate and efficient delivery to the mold. It is a preparatory step that has no direct value-added activities but is essential for maintaining process flow.

Vacuum bagging—This critical step involves sealing the composite structure under a vacuum, ensuring optimal resin infusion and void reduction. Proper execution is vital for achieving the desired material properties.

Resin infusion—During this phase, resin is infused into the composite structure, a process that directly impacts the strength, durability, and overall quality of the final product.

Post-Infusion—This phase includes curing and stabilizing the structure to achieve its final mechanical properties, often requiring precise environmental controls to ensure consistency.

Demolding—The final stage involves carefully removing the cured composite structure from the mold. This labor-intensive phase requires attention to avoid damaging the finished product.

The analysis of these phases was focused on the KPIs, which were selected by resin infusion experts and validated by the company. The baseline formulation provides a comprehensive understanding of the current process performance, setting a foundation for implementing advanced manufacturing solutions.

2.2. Methodological Approach

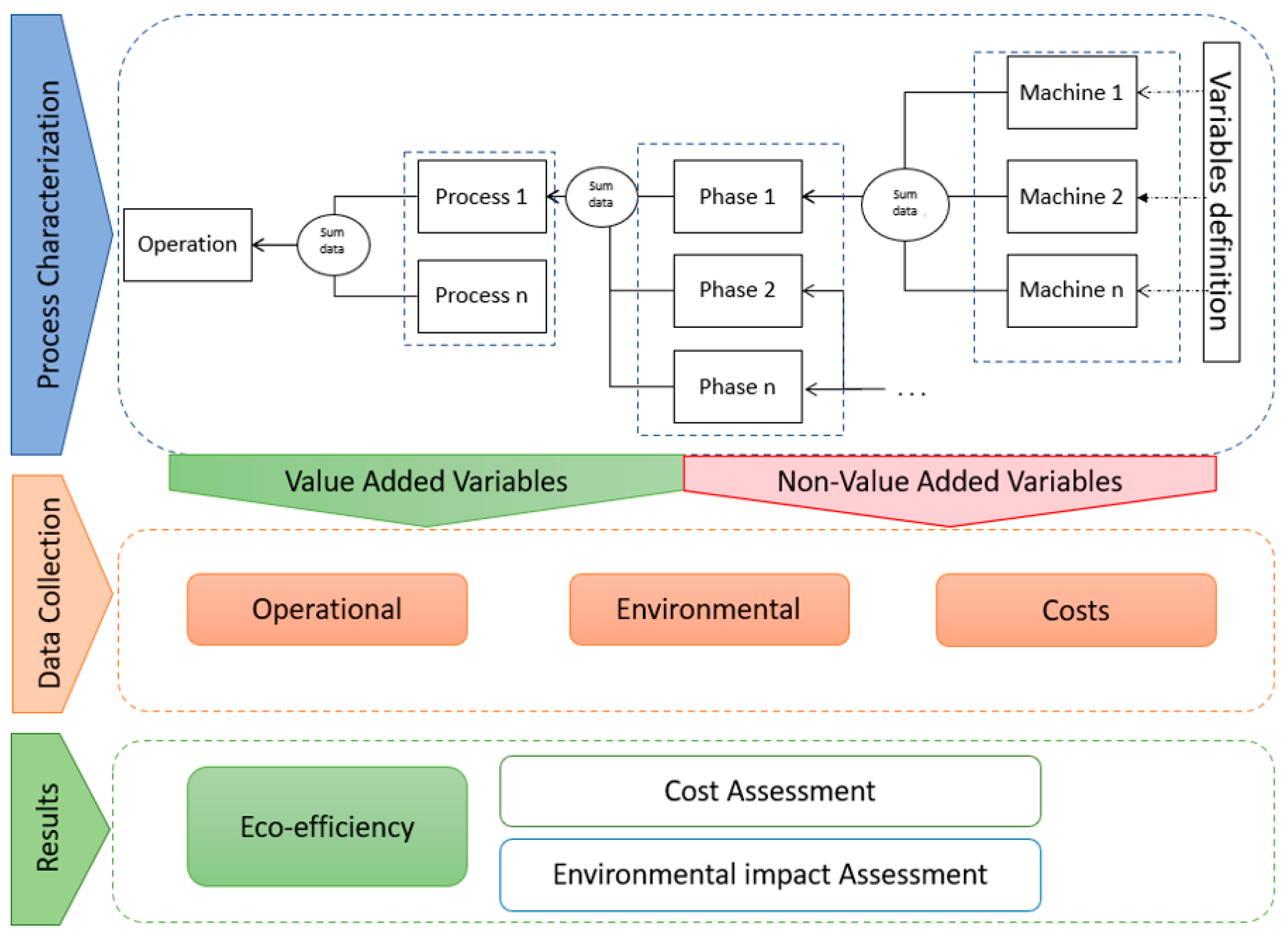

To conduct the eco-efficiency assessment, the methodology presented by [

11] was used as a foundation. The principles of the MSM approach were considered to conduct the analytical mapping of the processes, through the definition of a set of specific KPIs that reflects the efficiency of resource utilization, the costs related to misuses and inefficiencies, and other variables such as environmental ones. This tool was specifically developed to assess the overall performance of a production system through the non-dimensionalization of the different variables in a ratio between the portion of the “added value” variables and the sum of the “added and non-added value” variables, as expressed in [

11]. Ratios below 100% reflect inefficiencies, allowing us to identify process steps that should be carefully analyzed to improve the overall performance.

In this context, the method applied in this study involves a multi-level analysis implemented by following the diagram illustrated in

Figure 3. Operational, environmental and economic data were collected by the companies throughout the entire process flow, from the overall operation sequence down to the individual machines involved in each step. Due to the difficulty of collecting some data, some assumptions were considered, such as waste generation and time spent on visual inspection. These assumptions were based on workers’ expertise and the company’s historical data. Each phase was analyzed and classified as either value-added (VA) or non-value-added (NVA). VA activities are those that transform the product from raw material into a finished component, involving physical or chemical changes such as machining or assembly. In contrast, NVA activities do not generate changes in the product’s characteristics, even though they are often necessary within the process, such as inspection, cleaning, or transportation. Due to the difficulty in defining target values for each process step, mainly related to the complexity of the process, to conduct this baseline assessment, only the MSM concepts related to VA, NVA, and process characterization were used. Furthermore, the eco-efficiency was assessed using costs and Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI) data. The implementation of this methodology was intended to assess the performance of the process in several domains, namely operational, resource costs, and environmental impact, providing a global overview of the process efficiency.

2.3. Eco-Efficiency Assessment

Eco-efficiency evaluates the correlation between environmental and economic performance and is generally expressed by the ratio between economic value and environmental influence, represented by Equation (1) [

11].

This parameter emphasizes activities that deliver higher value while minimizing material, energy inputs, and emissions, combining cost assessments with a systematic evaluation of environmental impacts.

The cost analysis provides a detailed understanding of operational expenses, including labor, materials, and energy costs. Labor costs, influenced by task completion time, play a critical role in accurate cost allocation. The integration of cost analysis with process flow analysis reveals cost dynamics and highlights phases with significant expenses. In turn, the environmental assessment involves the compilation of a comprehensive Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI), cataloging inputs and outputs for each manufacturing phase. Key data points include resource consumption, energy use, and waste generation. Using the LCI, impact assessments translate collected data into quantifiable environmental impacts across categories.

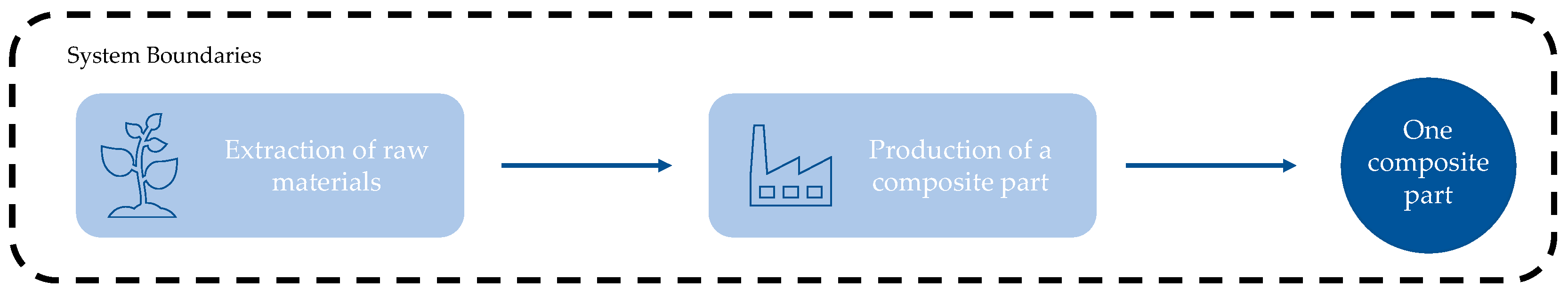

The environmental assessment applies the standardized LCA methodology (ISO 14040 and 14044 [

21,

22]) to determine the potential environmental impacts of the composite components throughout their production processes. The goal of the LCA was to identify environmental hotspots in the manufacturing of two representative composite components and to support industrial decision-making for material and process selection.

The functional unit adopted corresponds to one manufactured composite component (either an aerospace or a shipbuilding application). The reference flow consists of the amount of materials and energy required to manufacture one complete part. Primary data were collected directly from the industrial partners covering material inputs, energy use, and waste outputs for each process step. For the aerospace case study, the conditions of Italy were considered, whereas for the shipbuilding case study, Israel’s conditions were applied. Whenever feasible, European conditions were considered; otherwise, global conditions were assumed. The LCA study follows a cradle-to-gate system boundary, including raw material extraction and manufacturing of one composite part. Infrastructure emissions were excluded. The system boundaries are presented in

Figure 4.

For the environmental analysis, the inventory was constructed based on information provided by the manufacturers through Excel files containing information related to materials and energy consumption. The collected data were cross-referenced with the processes in the Ecoinvent life-cycle database version 3.7.1 to obtain background data on mass and energy flows related to the extraction and production of raw materials. Allocation at the point of substitution (APOS) was chosen for the modeling as it accounts for the entire production system, reflecting all connections with other systems whilst including all potential flows for secondary materials.

Table 2 shows the correspondence between materials and energy in the ecoinvent v3.7.1.

The collected LCI was modeled in the SimaPro v9.2.0.2 software using the ReCiPe 2016 Hierarchist (H) method to quantify the environmental impacts at the Endpoint level. At the Endpoint level, environmental impacts are assessed in terms of their long-term consequences, emphasizing broad areas of protection such as human health, ecosystem integrity, and the availability of natural resources. The Endpoints were then aggregated into three damage categories: human health, expressed in Disability-Adjusted Life Years; ecosystems, expressed in species.yr; and resources, expressed in USD. The overall impact score for each analyzed process was calculated as the sum of the normalized and weighted indicators expressed in ecopoints (Pt). In the end, the results are comparable across the manufacturing phase.

The proposed methodology aligns environmental and cost data in order to quantify the eco-efficiency of manufacturing processes, in this case related to the production of boats and aircraft structural components. The following chapter presents the results obtained from the implementation of this dual approach. Process steps characterized by high-cost and high-impact operations will be identified, allowing the definition of targeted strategies to reduce costs and environmental impacts, in order to optimize both economic and environmental performance.

3. Results and Discussion

This section focuses on the main results regarding cost, environmental impact, and eco-efficiency assessment of the two use cases from the aerospace and shipbuilding sectors.

3.1. Data Collection

Data were collected by the use cases in their production site and analyzed and classified based on VA and NVA activities. This procedure was carefully conducted by process engineers, following their own measurements and data collection methods.

The process flow related to the aerospace use case, and presented in

Figure 1, was analyzed in detail, focusing on the time required for each phase, consumed energy, labor costs, and the VA/NVA classification for each task. The results presented in

Table 3 demonstrate that specific phases, such as resin infusion, spent a higher amount of time on NVA activities, due to the time required for resin curing. That represents a potential opportunity for improvements, if additional developments allow the reduction of this sub-step. Lastly, the labor cost of each process phase was established by the company, considering the operation time and the number of workers, as expressed in

Table 3. Moreover, considering the relevance of visual inspection in this process, this variable was estimated and identified in the sub-steps where that task was conducted. Based on this preliminary assessment, the cost analysis was performed by combining the material, energy, and labor costs. Due to data confidentiality, costs per operation are not provided, nor is the list of consumables and equipment, nor the energy consumed by them.

The same approach was conducted for the shipbuilding use case. Starting with the VA/NVA classification, the results presented in

Table 4 demonstrate that some phases, such as resin plant layout and demolding, do not have activities that add value to the final product, representing a potential opportunity for improvements.

3.2. Aerospace Use Case Assessment

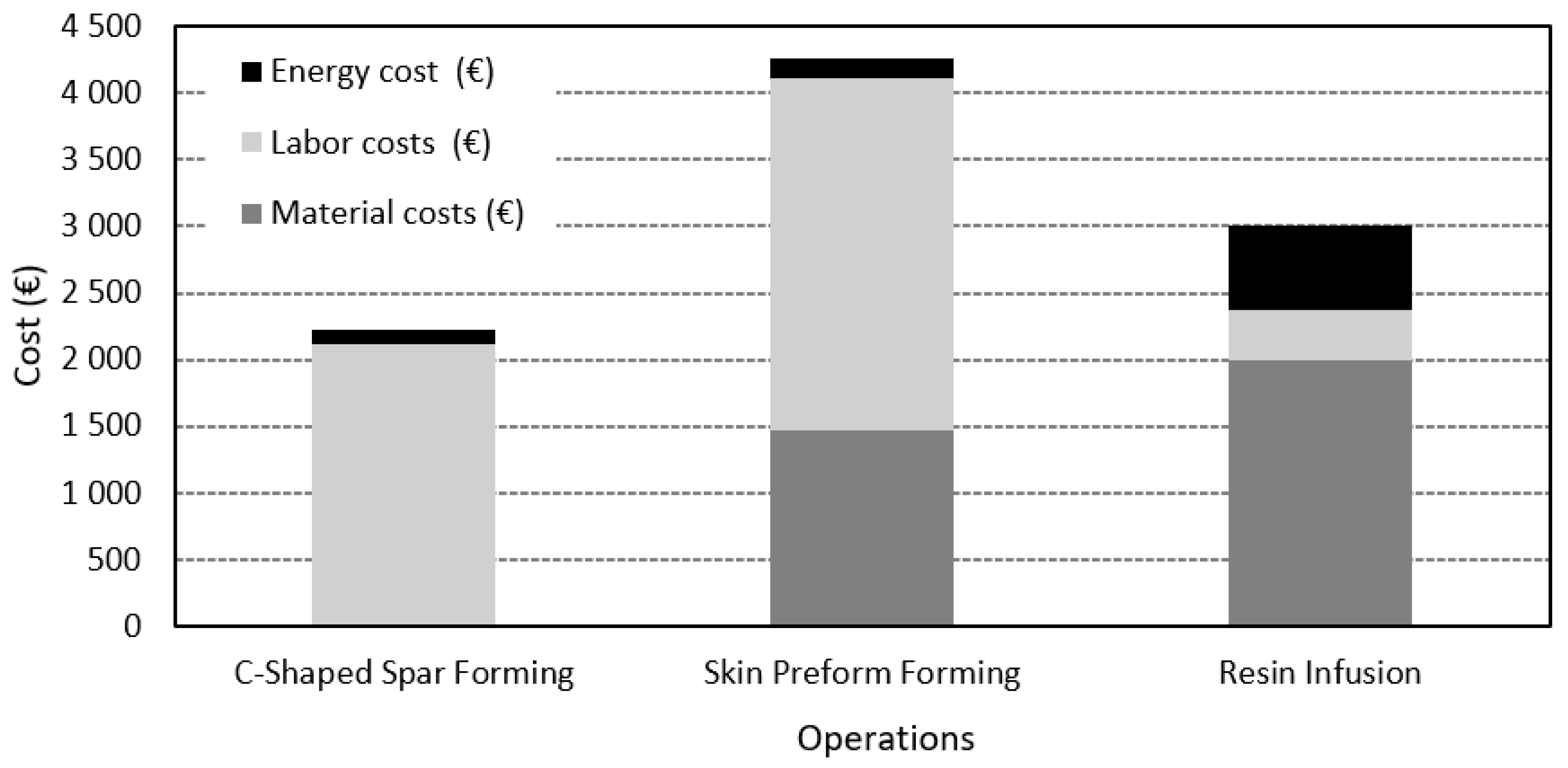

Based on the data collected, a cost assessment of the manufacturing process was conducted, including material, energy, and labor expenses. As illustrated in

Figure 5, labor costs emerged as the primary contributor, accounting for approximately 54% of the total costs. Among the various process operations, skin preform forming was identified as the most expensive, followed by C-shaped-spar forming and resin infusion.

In the case of resin infusion, the high costs are mostly attributed to material consumption, specifically resin. Material waste in this process results in significant expenses, underscoring the importance of implementing mechanisms to monitor and control resin usage, thereby minimizing inefficiencies. On the other hand, energy consumption was found to contribute the least to overall costs across the three operations.

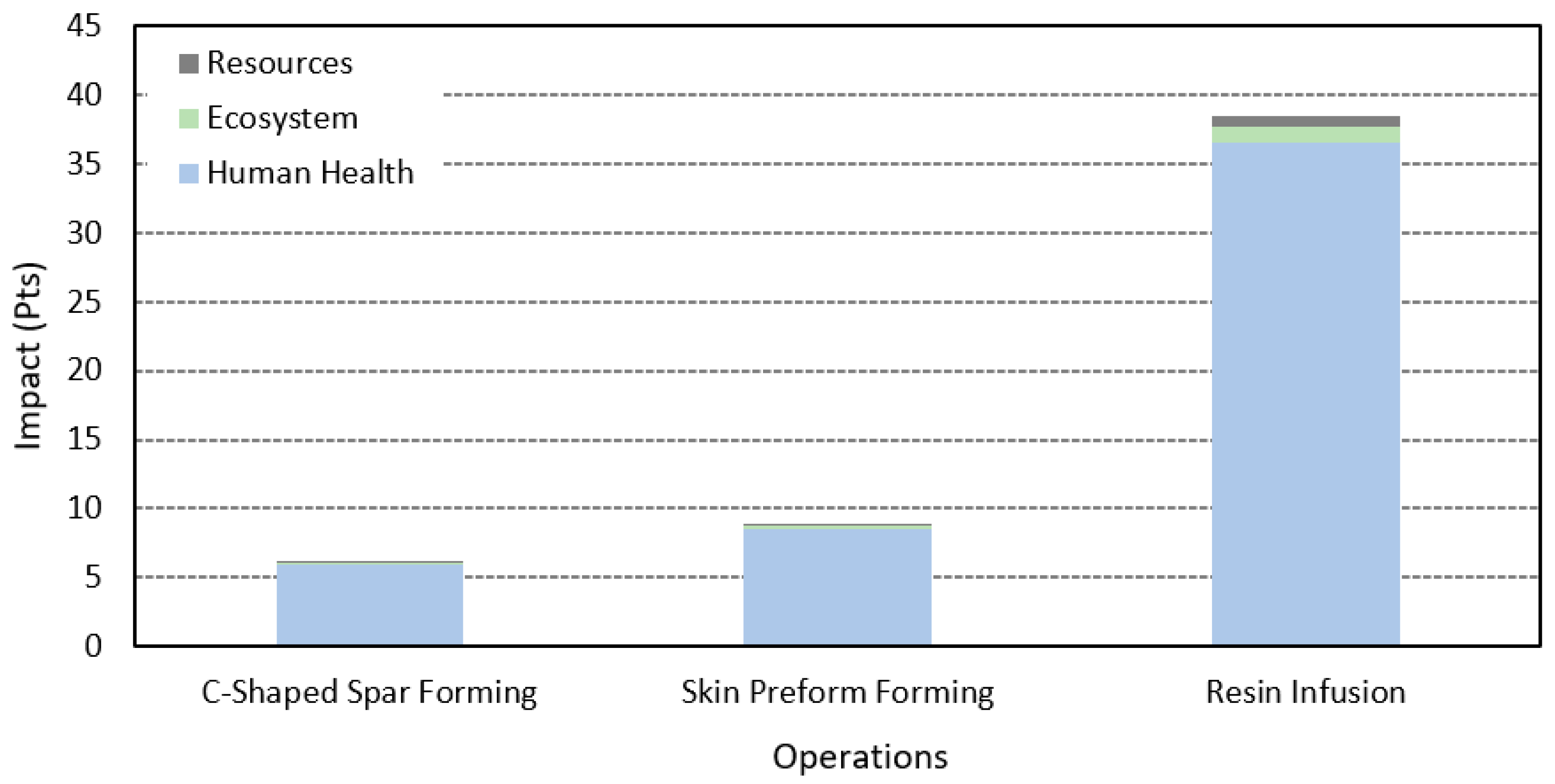

The environmental impacts related to the manufacturing process are summarized in

Figure 6, presented on an ecopoint (Pt) scale reflecting the damage caused by resource usage. The results reveal that the resin infusion phase accounts for the majority of the environmental impacts, followed by the skin preform forming phase. Together, these two operations represent approximately 88% of the total impacts, which is consistent with the relatively low resource and energy usage during the C-shaped-spar forming phase. Human health emerged as the most critical concern, primarily due to the risks faced by workers during manufacturing. These risks are linked to exposure, inhalation, and direct contact with hazardous compounds, which can lead to respiratory issues and long-term health effects.

Additionally, the difficulty in accurately quantifying waste generated during the process reduces the apparent impact on ecosystems; therefore, this factor is likely to be underestimated. Recommendations were provided to the company to improve its waste measurement process in order to obtain a realistic evaluation of the environmental effects caused by the process.

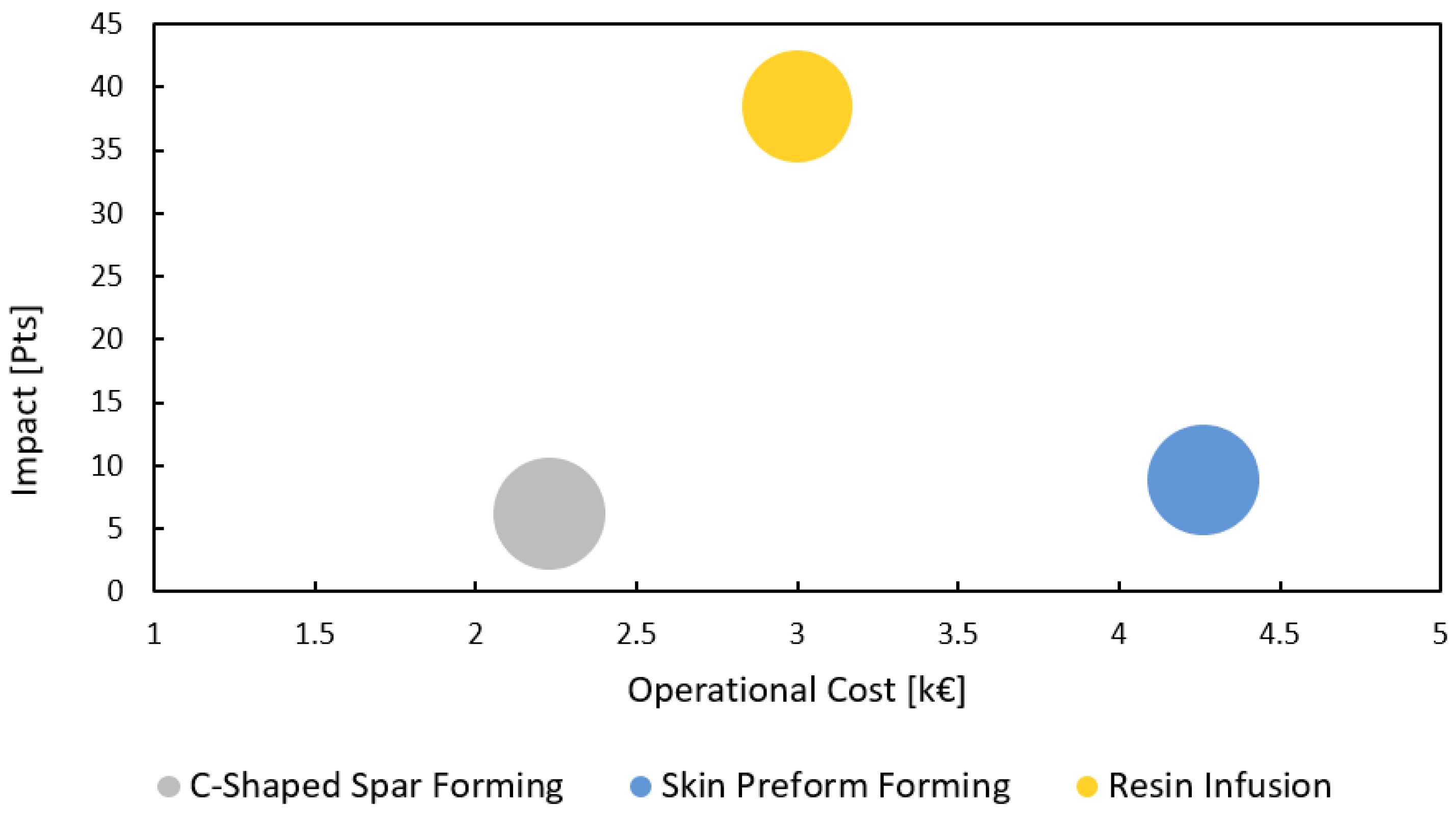

Combining the information obtained from the previous analysis, the eco-efficiency analysis was conducted to compare the environmental impacts with the associated process costs.

Figure 7 shows the eco-efficiency chart, where the

y-axis corresponds to the environmental impacts (Pts) and the

x-axis corresponds to the total operational costs (kEUR) associated with the selected process phases.

The analysis of the chart reveals distinct trends in the environmental and operational cost impacts of the manufacturing operations. The C-shaped-spar-forming phase shows the lowest combined impact and cost, whereas resin infusion has the highest environmental impact, and skin preform forming incurs the highest operational costs. These findings highlight the need to closely examine process variables that significantly influence these outcomes.

This insight reveals the importance of adopting digitalization solutions as enablers to improve ZWM. The integration of an advanced monitoring and data acquisition system, especially in the resin infusion process, is expected to enhance the overall eco-efficiency of the process. Furthermore, as noted earlier, the implementation of additional control points and measurement systems in high-impact operations is crucial. Such measures will allow for more precise process characterization, leading to reduced waste, minimized inefficiencies, and improved sustainability throughout the manufacturing life cycle.

3.3. Shipbuilding Use Case Assessment

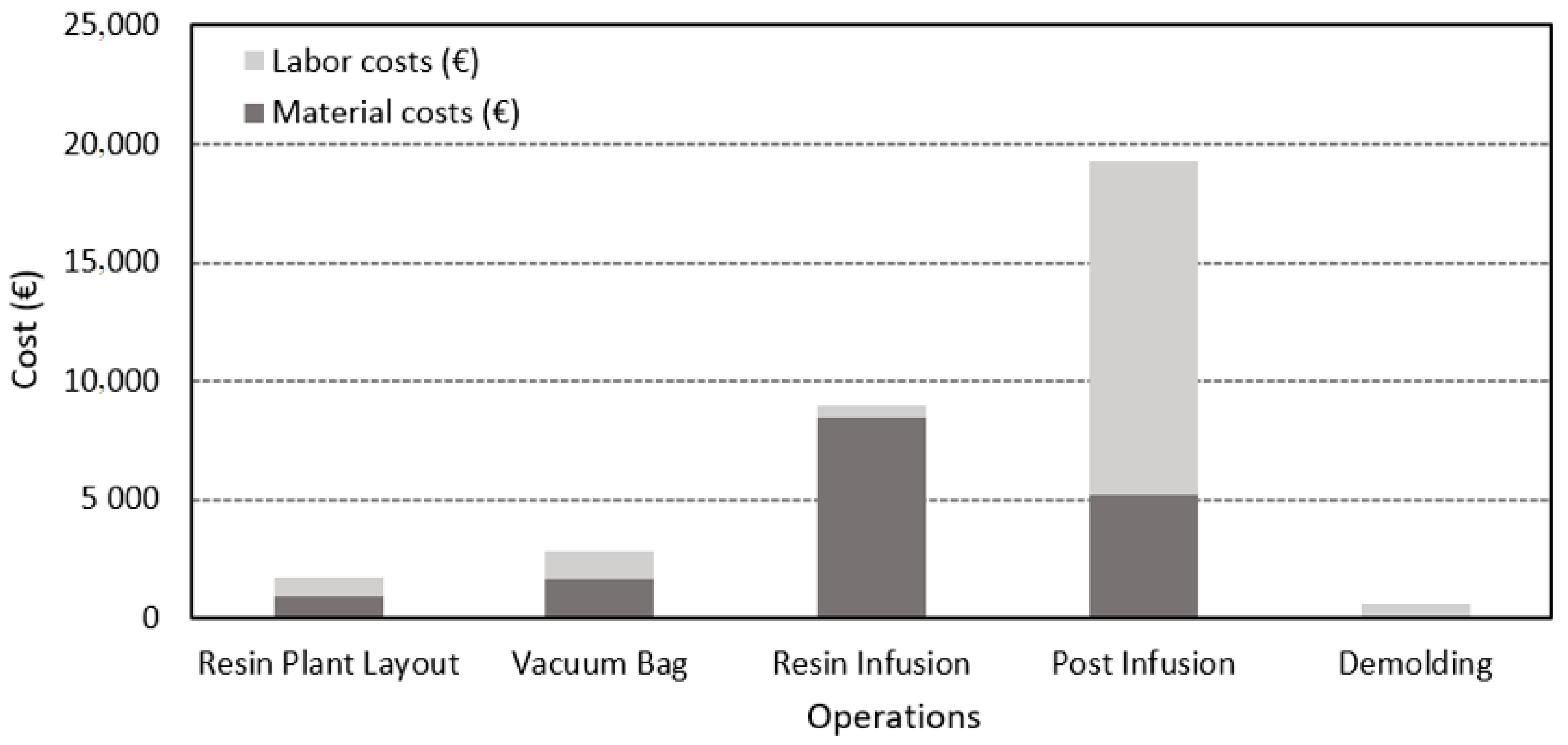

Building on the evaluations outlined in earlier sections, a cost analysis of the shipbuilding manufacturing process was conducted by integrating material and labor expenses. Due to current limitations, energy consumption costs for this use case could not be measured and were, therefore, excluded from this analysis. However, as indicated in

Figure 8, the Post-Infusion phase emerges as the largest contributor to overall costs, accounting for approximately 57% of the total. This is primarily attributed to its significant labor requirements, as this phase involves a huge amount of time among those assessed.

A detailed assessment of the Post-Infusion phase is essential to identify any inefficiencies that may be extending labor time and driving up costs, or to integrate technologies and methods that support operators in their manual activities. Additionally, resin infusion stands out as having the highest material costs. Monitoring this process closely and implementing strategies to minimize material waste are critical steps to enhance efficiency and reduce overall expenses.

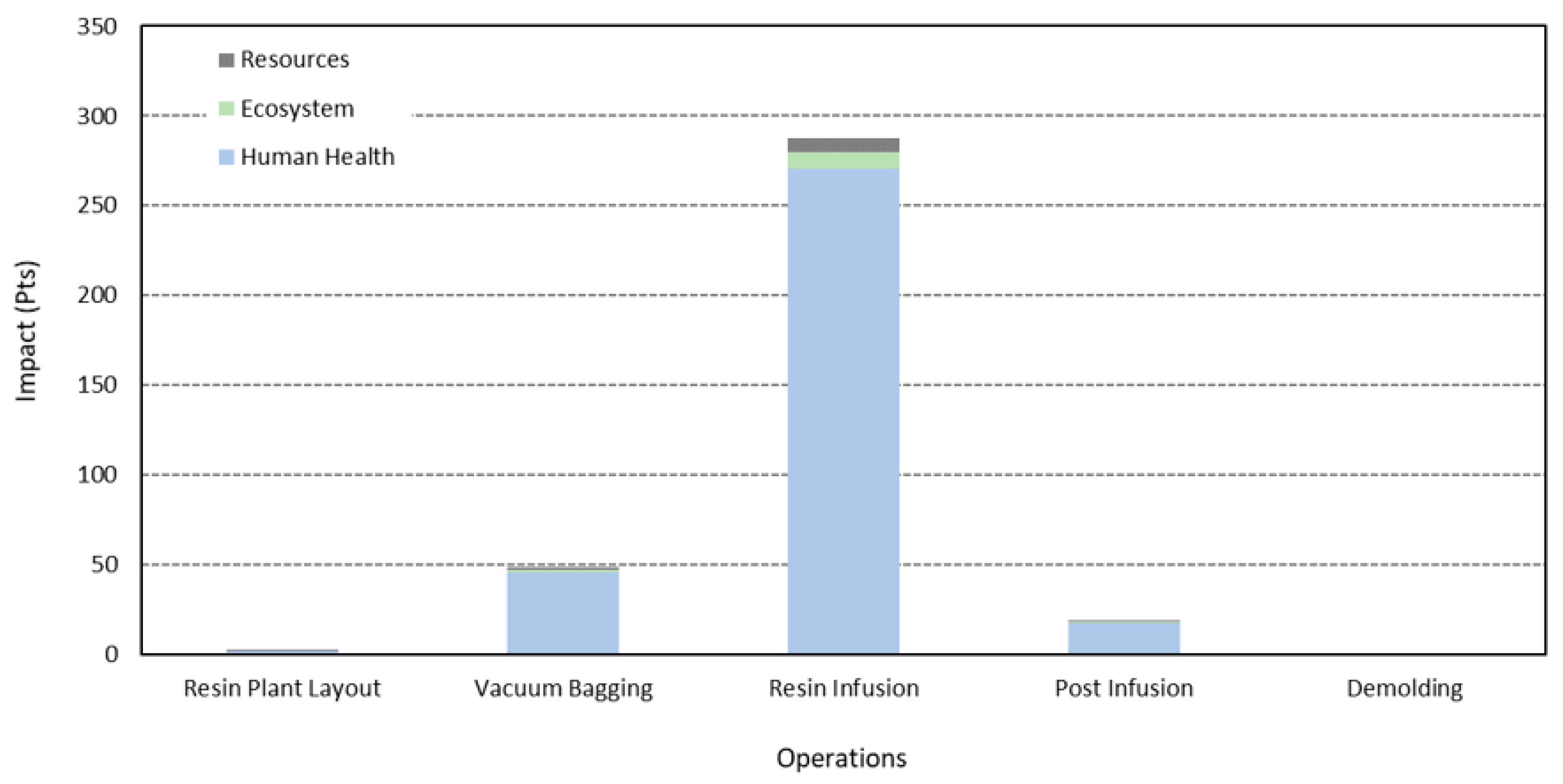

The environmental impact assessment is illustrated in

Figure 9, following the same approach previously detailed. The resin infusion phase accounts for the highest proportion of environmental impacts, approximately 79% of the total, primarily due to resin consumption. Following this, the vacuum-bagging phase contributes around 13% of the overall impact. These findings highlight the need to minimize waste generated during these processes, particularly in resin infusion, to mitigate their environmental footprint. Accurate tracking of total material consumption is essential to identify where significant losses occur in the process and to develop strategies or operational improvements to minimize waste and enhance process efficiency.

When analyzing the impact across various domains, a pattern similar to that observed in the aerospace case study emerges. The greatest concern lies in human health, mainly due to risks associated with the manufacturing process. A thorough assessment of each process stage’s impact on worker safety is strongly recommended to identify potential hazards and implement effective mitigation measures.

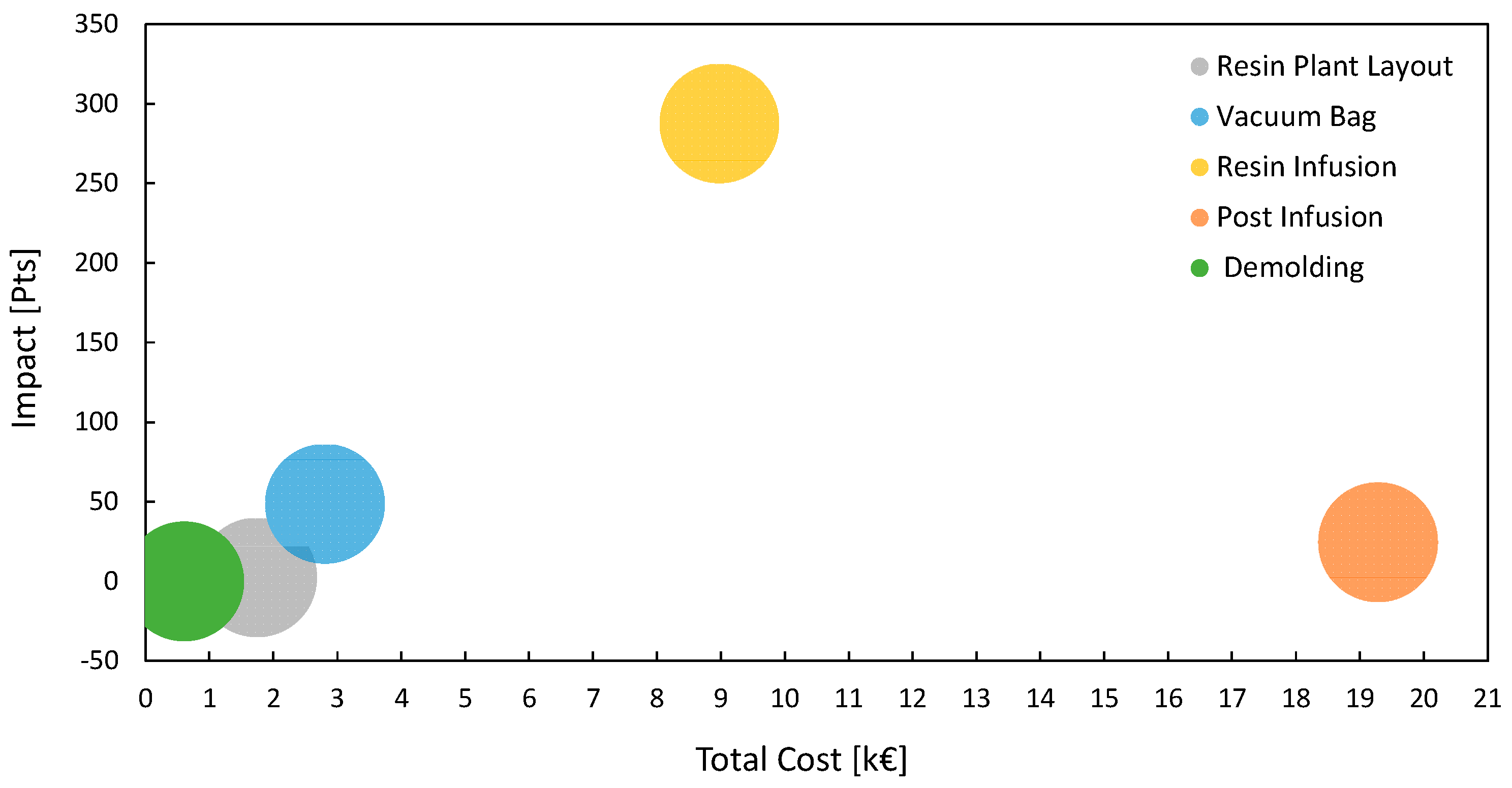

The eco-efficiency analysis was performed using the collected data to evaluate the relationship between environmental impacts and associated process costs. Thus,

Figure 10 presents the eco-efficiency result, following the approach previously presented. The analysis reveals that significant resources and environmental impacts are allocated to activities with low VA-to-NVA ratios.

From the chart, it is evident that the Resin Plant Layout and demolding phases exhibit the lowest impact and cost values, which aligns with expectations, as these phases are characterized by a high proportion of NVA activities. In contrast, the resin infusion phase shows considerably higher environmental impacts when compared to other process steps and needs attention since it is the primary factor for the decreasing of the product’s overall sustainability. The efficiency of the material used, resin losses, and scrap rates play an important role in contributing to the reduction in the process’s performance. In this context, the FLASHCOMP project is working on the implementation of a digital process through computer vision that intends to contribute to the improvement of this process. Although the Post-Infusion phase demonstrates a low environmental impact, it is associated with high operational costs due to the extensive time required. This discrepancy highlights inefficiencies related to process duration rather than material consumption, highlighting the opportunity for optimization through improved process control and cycle-time reduction. A detailed analysis of this process step is recommended to identify opportunities for improvement and to implement strategies that enhance its overall efficiency.

3.4. Comparative Analysis Between the Two Use Cases

Across both sectors, aerospace and shipbuilding, the study revealed that resin infusion is consistently the most critical and resource-intensive phase, contributing significantly to environmental impact and material costs. This similarity highlights the cross-sector relevance of monitoring, automation, and process optimization technologies, which can improve eco-efficiency regardless of the application. Moreover, in both cases, NVA activities such as setup, inspection, and material handling were identified as major sources of inefficiency, reinforcing the need for digital tools for process monitoring and data-driven decision support. Sector-specific findings were also observed: in the aerospace sector, the focus on precision and defect minimization drives high labor costs and strict quality assurance, while in shipbuilding, manual operations and large-scale part handling contribute to longer cycle times and waste generation. These differences reflect the contrast in the production scales and certification requirements.

Table 5 summarizes the main similarities and differences in process characteristics, efficiency drivers, and sustainability priorities between both sectors, allowing us to highlight the relevance of the results obtained and supporting the adaptability of the proposed eco-efficiency framework to different industrial contexts.

4. Main Challenges and Lessons Learned

The implementation of eco-efficiency assessment methodologies in complex manufacturing environments revealed several challenges and key lessons learned. These are mainly related to data availability, methodological limitations, and the accuracy of performance indicators.

The collection of reliable data emerged as one of the most critical and complex aspects of the study. Not all parameters and variables are systematically recorded or monitored by the companies, due to the complexity of the process, which limits the accuracy of the datasets. Therefore, data gathering became an iterative process, requiring multiple rounds of refinement to define how KPIs could be effectively collected and used to characterize the process efficiency with accuracy. In many cases, environmental impact data were based on assumptions rather than direct measurements, which further increased the uncertainty of the results. Another limitation concerned the measurement of waste generation. Quantifying the exact amount of waste across different process stages proved to be difficult, and the collected data often required further validation to ensure accuracy. Similarly, assessing process quality and the impact of vision detection technologies throughout the production stages required a more detailed analysis, particularly in defining precise metrics such as the percentage of reworked or repaired parts.

Another limitation detected was related to the use of the overall MSM as a methodology to quantify process efficiency, since it requires the comparison between target values and measured values. For the baseline scenario, however, the difficulty in defining appropriate target values constrained the application of MSM. Consequently, the baselines presented in this work were primarily built on the actual values collected from the use cases. While these provided a useful quantification of the selected KPIs, the reliance on assumptions and incomplete reference targets limited the robustness of the analysis. This deviation highlights that, although MSM provides a valuable structure for integrating multi-dimensional efficiency indicators, its implementation requires consistent and well-defined benchmarks, which were not always available in industry.

From these challenges, several important lessons were obtained. First, the results highlight the urgent need for companies to invest in measurement systems and monitoring methods that enable the continuous and consistent collection of data. Such systems would allow for real-time tracking of process performance, enabling inefficiencies to be detected at early stages rather than only retrospectively. Second, the study showed that the detailed characterization of process steps is essential for accurate eco-efficiency assessment. Given the complexity of composite manufacturing, specific data will inevitably be difficult to quantify, and need assumptions. However, these assumptions must be carefully validated to avoid significant discrepancies between estimated and real values, which can undermine the reliability of the conclusions. Finally, the collaboration with industrial partners was crucial in highlighting the practical limitations of data collection in real-world settings.

This work provided valuable insights, mainly that the success of eco-efficiency assessments in manufacturing is strongly dependent on the availability of accurate, continuous, and standardized data. By addressing these challenges through improved measurement systems and better-defined targets, future applications of the present eco-efficiency method and similar approaches can deliver more robust, actionable insights for both environmental and operational performance improvements. Furthermore, this study highlights that eco-efficiency assessments play a pivotal role in advancing zero-waste manufacturing goals. By systematically linking resource consumption, waste generation, and process performance, eco-efficiency provides the quantitative information needed to identify where waste is produced and how it can be prevented at the source. Unlike traditional waste management approaches that focus on end-of-line solutions, eco-efficiency enables the integration of preventive strategies directly into process design and operation. This proactive perspective is essential for zero-waste manufacturing, as it shifts the focus from merely reducing waste to its elimination through an optimized material flow, improved process control, and continuous monitoring. This work demonstrates that eco-efficiency acts as a diagnostic tool and as a strategic enabler, guiding companies toward manufacturing processes that are both resource-efficient and environmentally sustainable.

5. Conclusions

The comprehensive eco-efficiency assessment of composite manufacturing processes provided valuable insights into the interaction between environmental and economic performance across production phases. The analysis identified resin infusion as a major hotspot, primarily due to its high material consumption and associated costs, underscoring the need for material optimization strategies. Additionally, labor-intensive stages, such as Post-Infusion finishing and skin preform forming, were found to significantly influence total process costs, revealing potential inefficiencies in workflow design. These findings highlight priority areas for process innovation, automation, and resource efficiency improvements to enhance both sustainability and competitiveness in composite manufacturing. This baseline provides relevant information that allows researchers to identify, select, and prioritize the technological solutions to be developed and integrated into the manufacturing process. This will ensure that further improvements address the most impactful inefficiencies and sustainability challenges.

The eco-efficiency assessments highlighted that the high environmental impact of resin infusion needs enhanced waste monitoring and process optimization, while the labor-heavy operations require streamlined workflows to reduce operational time and associated costs. Implementing digitalization solutions, such as advanced monitoring systems and control points, has been shown to offer substantial potential for improving the eco-efficiency of processes. These systems enable precise characterization of resource consumption and waste generation, fostering informed decision-making for sustainability improvements.

Additionally, human health risks associated with hazardous compounds in processes like resin infusion highlight the need for rigorous safety protocols and exposure reduction strategies. Addressing these issues is expected to enhance worker well-being and align with broader sustainability goals. This work shows the advantages of the integration of eco-efficiency assessments into manufacturing workflows, offering a strategic pathway to balance environmental and economic objectives.

Finally, the integration of eco-efficiency assessments with zero-waste manufacturing principles identifies unnecessary resource use and minimizes environmental burdens. By quantifying material and energy flows, eco-efficiency provides a structured framework to reveal where waste is generated and how it impacts both costs and sustainability. Through this assessment, companies can build on those insights and establish process improvements that prevent material losses, optimize resource utilization, and reduce non-value-added activities, in the direction of zero-waste manufacturing. This alignment contributes to environmental footprint reduction and enhances competitiveness and process resilience, leading companies toward more sustainable and resource-efficient composite manufacturing.