Poisson’s Ratio as the Master Variable: A Single-Parameter Energy-Conscious Model (PNE-BI) for Diagnosing Brittle–Ductile Transition in Deep Shales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Triaxial Compression Tests on Shale Under Different Confining Pressures

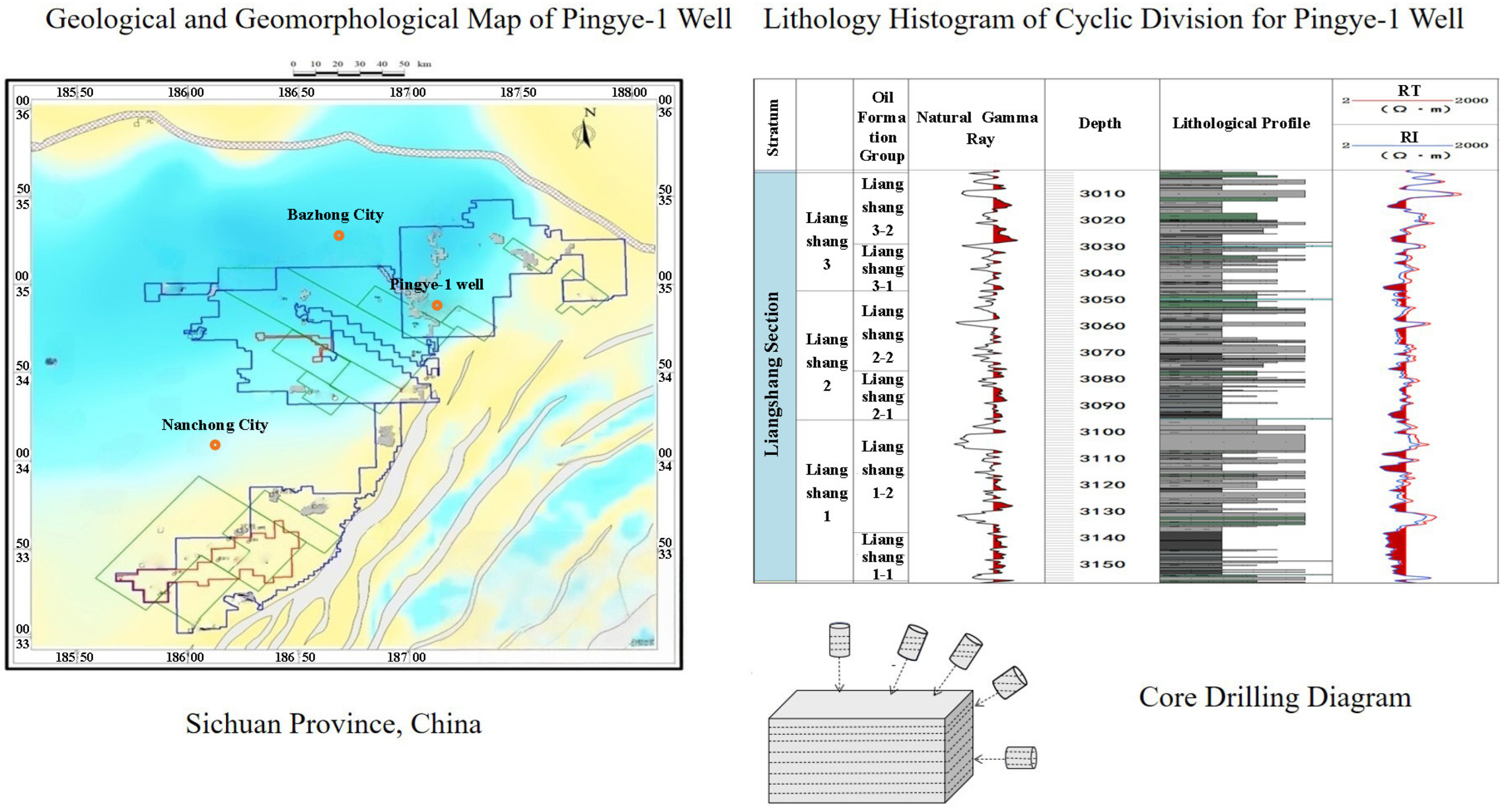

2.1. Geological Characteristics and Sample Preparation

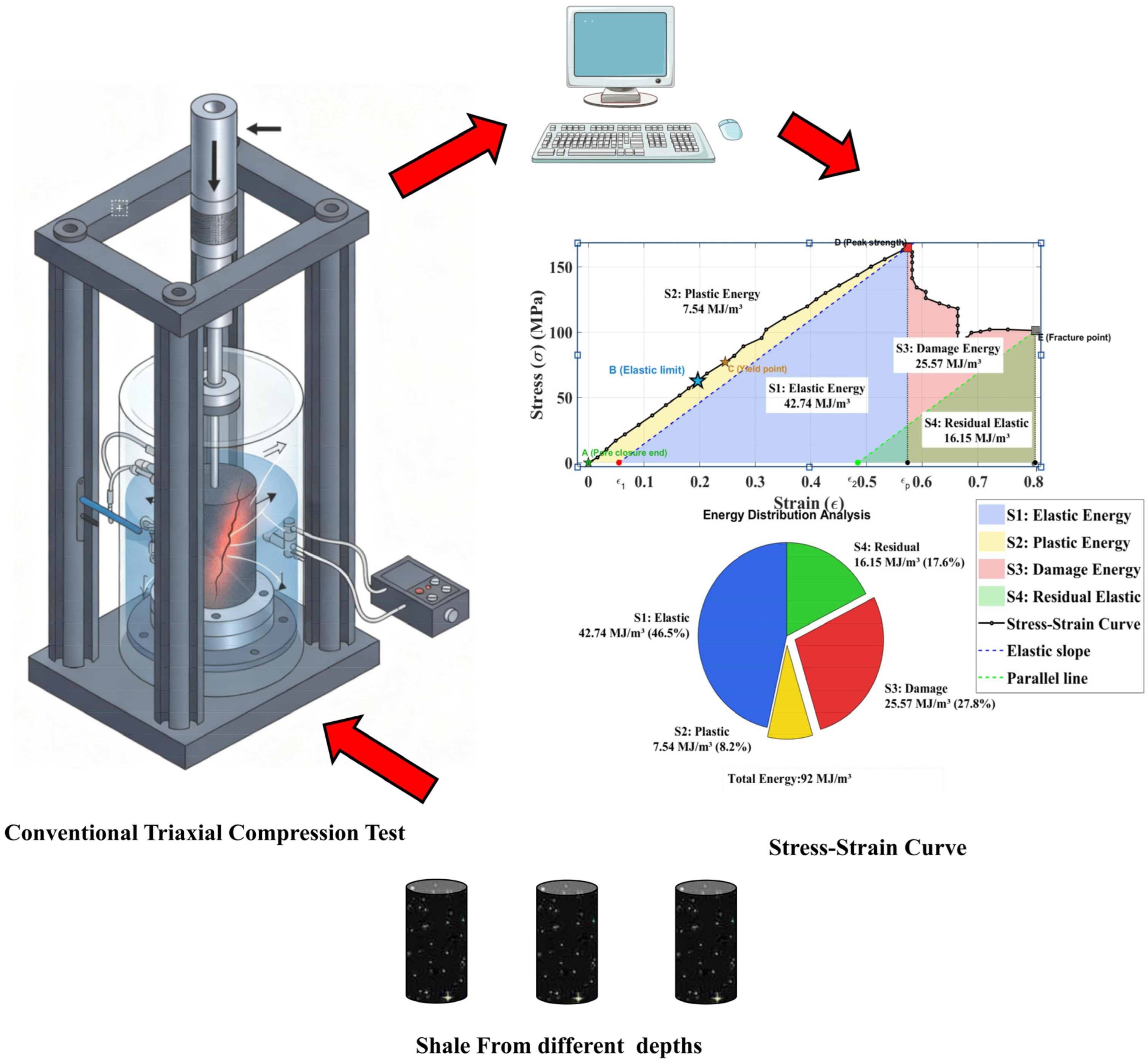

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Protocol

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

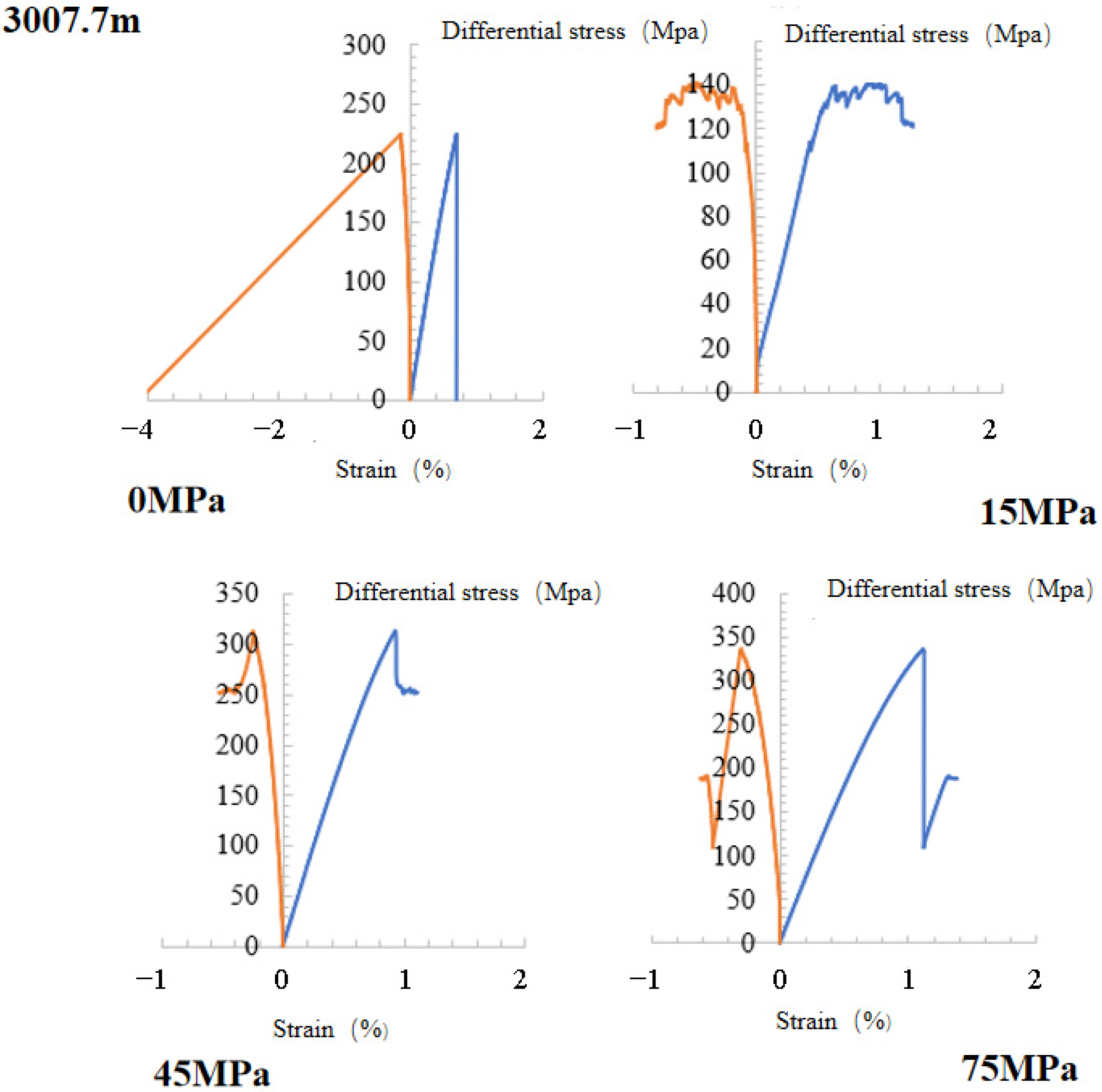

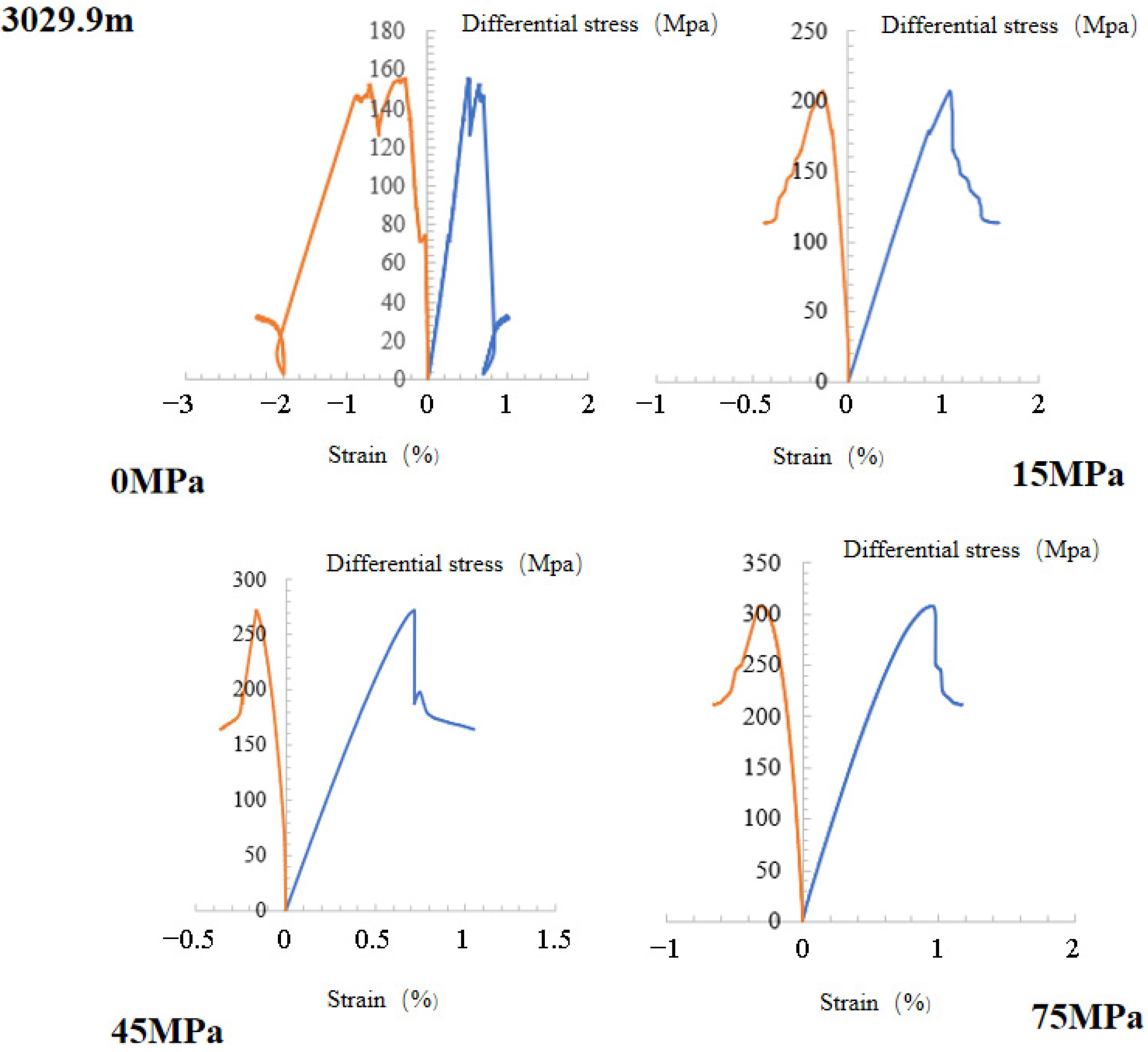

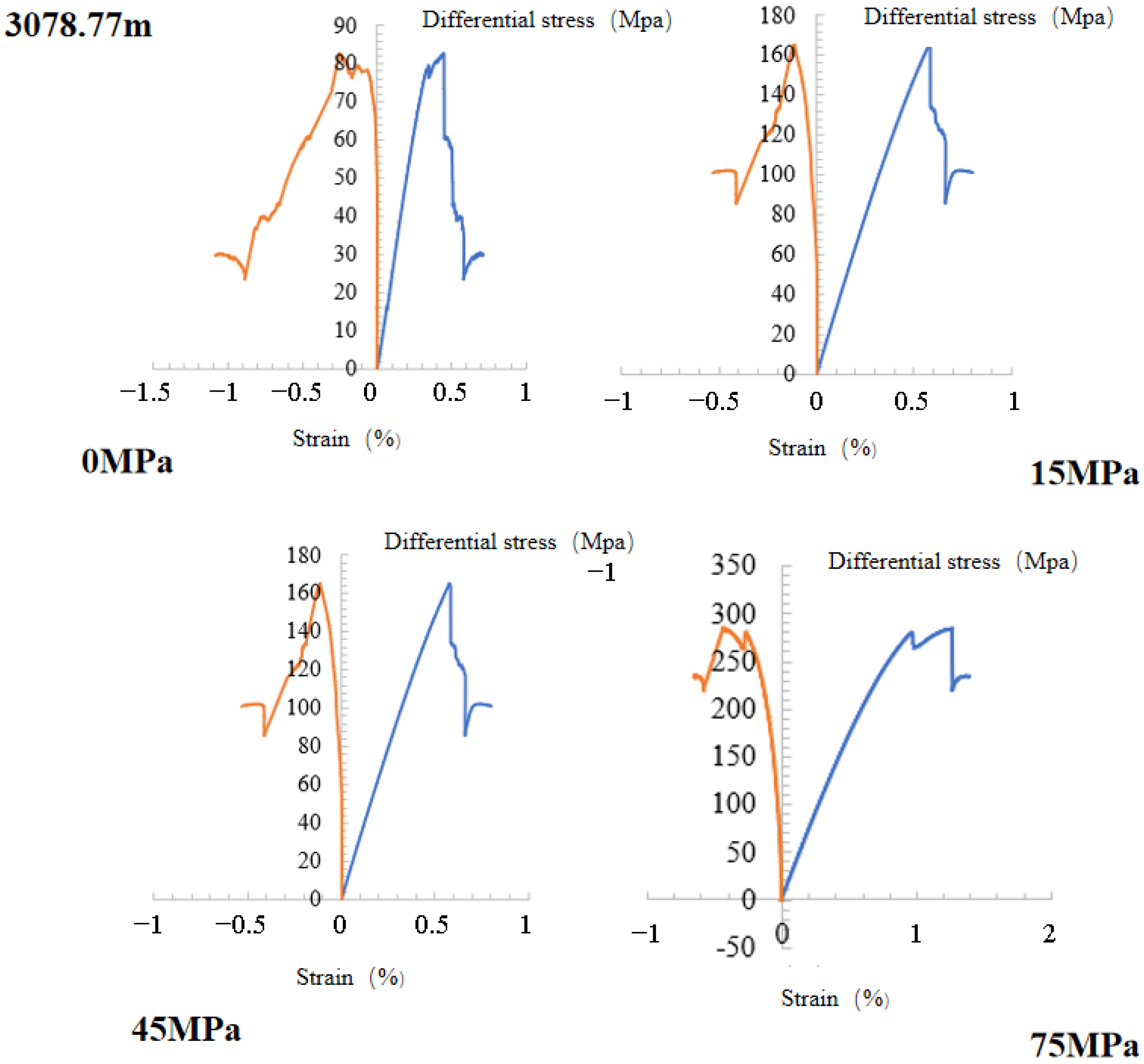

3.1. Stress–Strain Curves

3.2. Triaxial Test Results

4. Poisson’s Ratio-Based Brittle-Ductile Evaluation Model and Verification

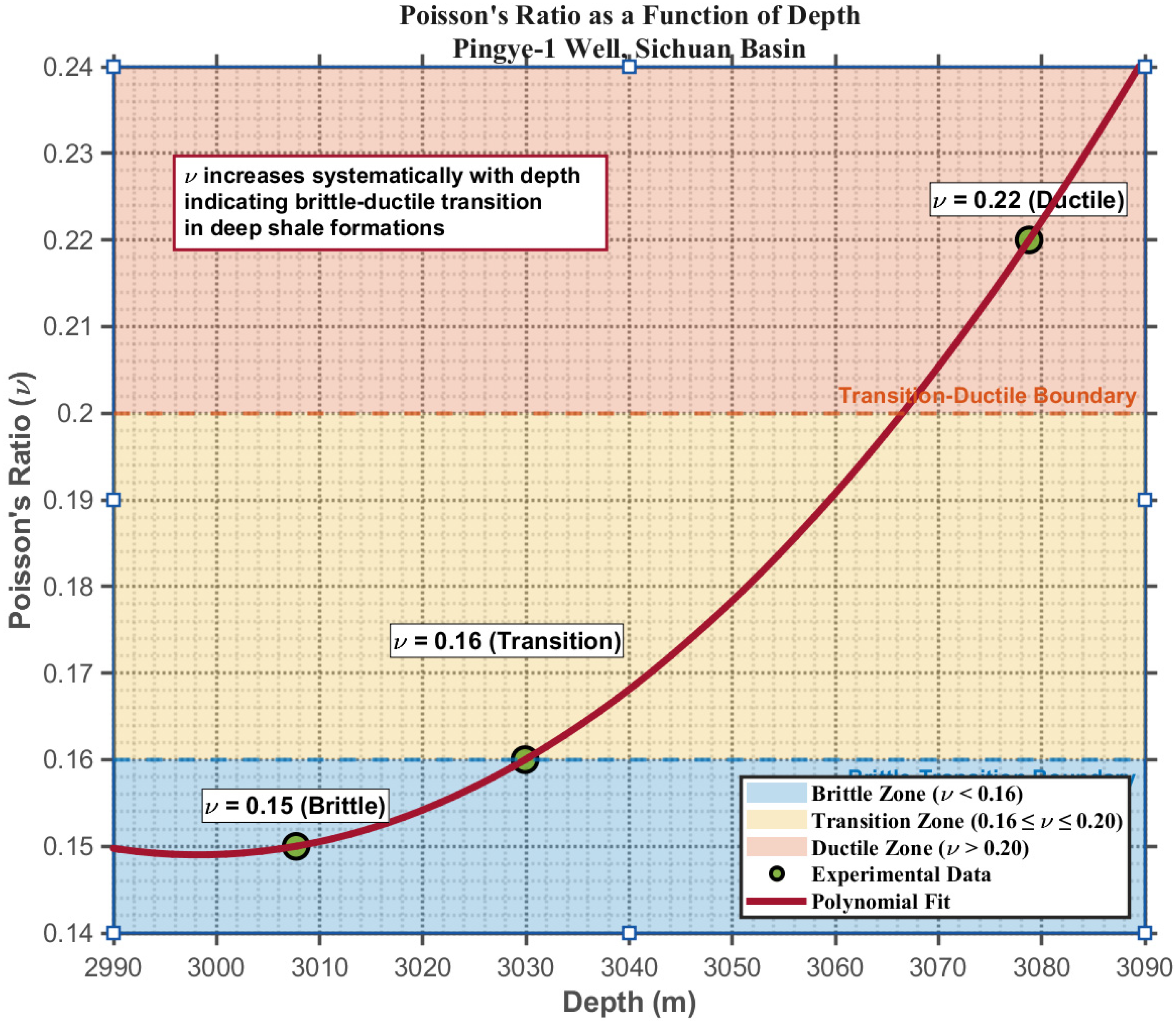

4.1. Poisson’s Ratio-Dominated Brittle-Ductile Transition Mechanism

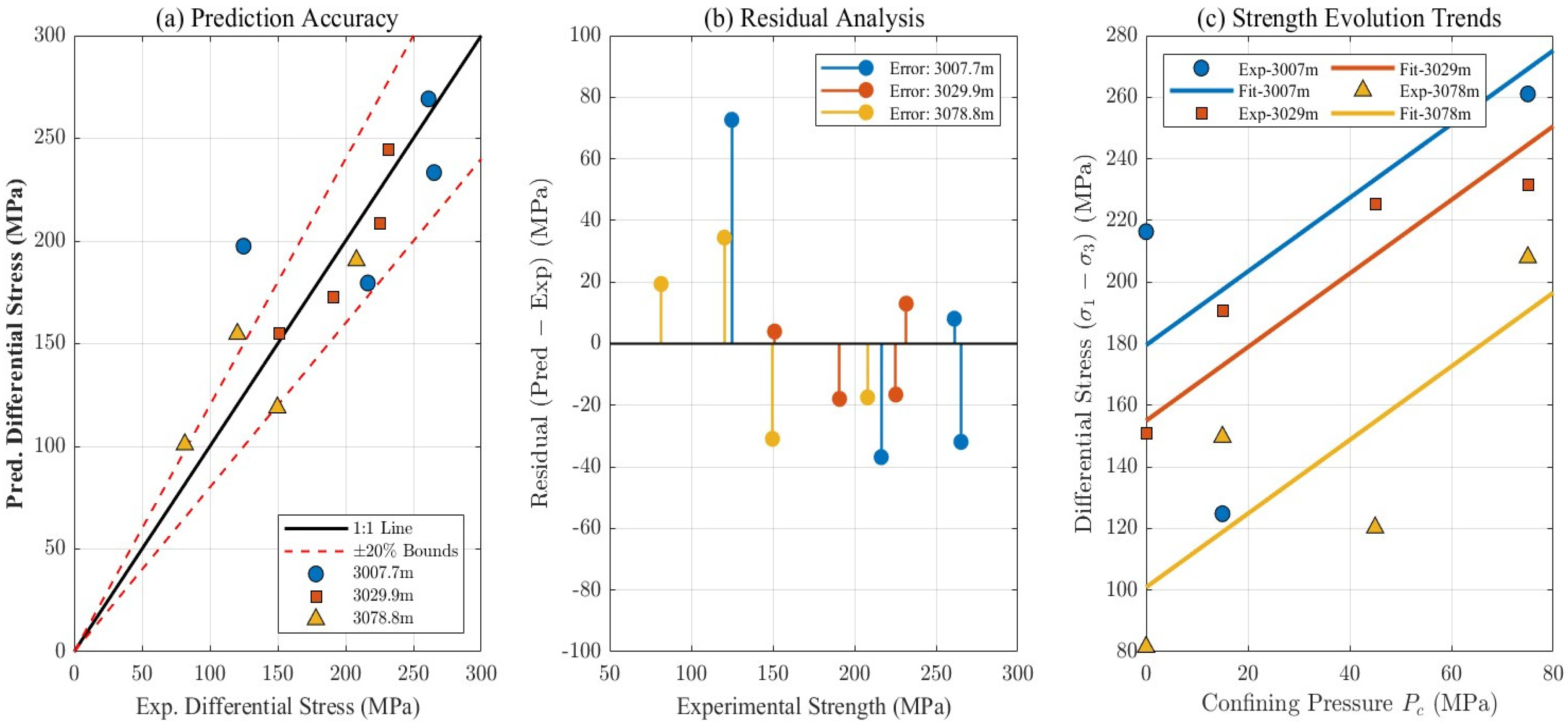

4.2. Modified Mohr-Coulomb Criterion

4.3. Brittle-Ductility Evaluation Model

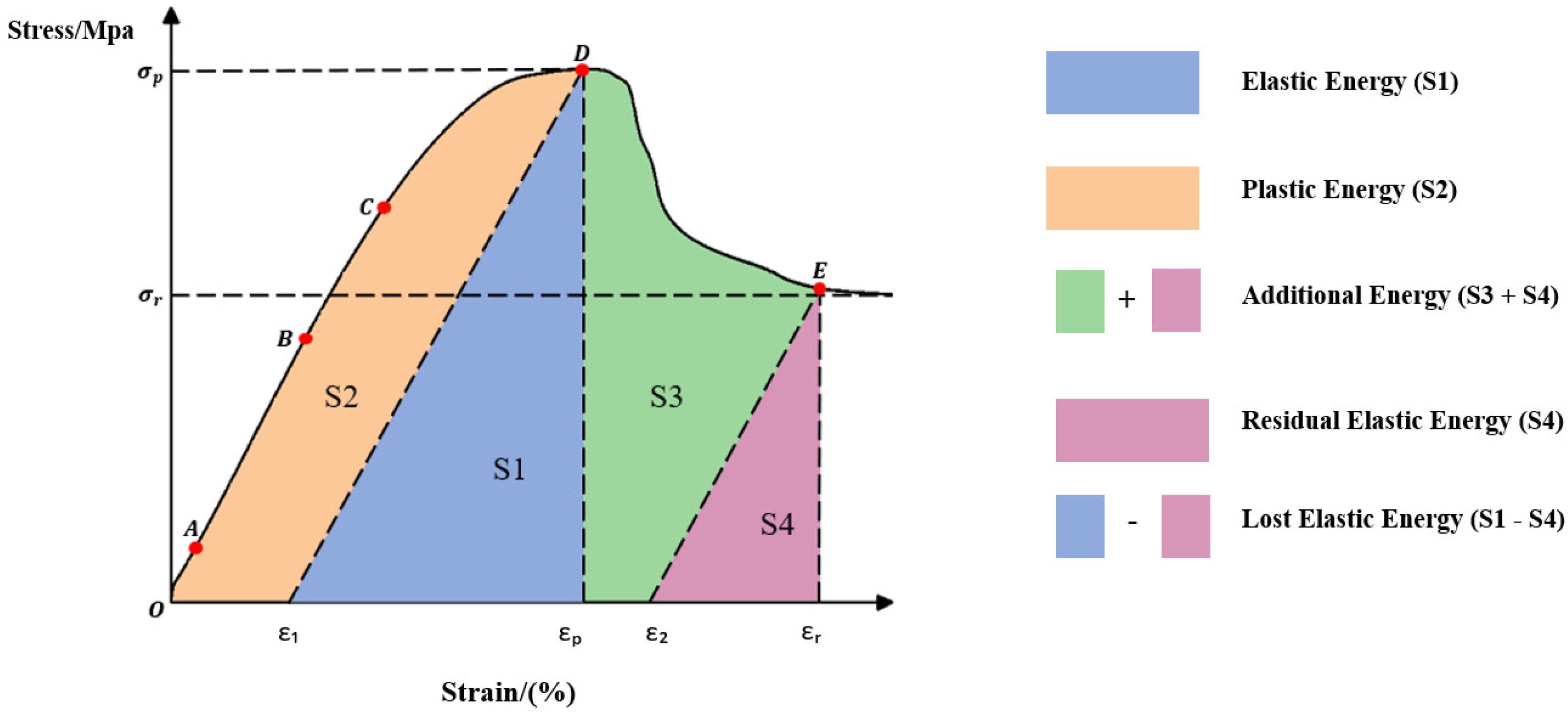

4.4. Innovative Poisson’s-Ratio-Regulated Energy Brittle-Ductile Model

4.5. Model Validation and Analysis

5. Field Application and Discussion

5.1. Representativeness of Thresholds

5.2. Quantitative Fracture Characterization and Field Verification

5.3. Quantitative Sensitivity Analysis and Justification for the Single-Parameter Model

5.4. Limitations and Future Scope

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Poisson’s ratio () emerges as the pivotal parameter governing brittle-ductile transition in deep shale, with triaxial experimental data confirming its systematic increase with depth—directly controlling fundamental shifts in rock failure modes. At < 0.16 (brittle zone), failure manifests as tensile-dominated longitudinal splitting. When ν reaches the critical threshold of 0.16–0.20 (transitional zone), failure shifts to conjugate shear. At > 0.22, clay mineral hydration intensifies, reducing intergranular sliding resistance; plastic flow dissipates > 70% of energy, triggering barreling deformation and suppressing macroscopic fracture. Energy evolution analyses (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10) reveal that rising weakens rock resistance to volumetric compression, inhibits brittle dilatant crack propagation, and redirects energy dissipation paths from elastic storage to plastic-damage synergy, ultimately driving the brittle-ductile transition.

- (2)

- The proposed Poisson’s Ratio-regulated Energy-based Brittleness Index (PNE-BI) uses ν as its sole input parameter. Through the innovative formula (where , the model quantifies energy rebalancing for engineering-grade diagnostics. The model validity was rigorously verified through multi-scale independent data. On the formation scale, the model accurately segmented the continuous lithological profile, aligning strictly with mineralogical boundaries (Quartz-rich vs. Clay-rich). On the micro-scale, physical CT scanning confirmed that the predicted brittle/ductile states correspond precisely to the transition from complex network fracturing to simple bedding-parallel slip. Increased ν elevates plastic dissipation efficiency (λ(ν) ↑ 25.0% as ν ↑ 0.15 → 0.22), significantly suppressing crack growth (S3 damage energy ↓ 65.4% at 3078.77 m/75 MPa versus 0 MPa), and reveals ν-confinement synergy: confining pressure enhances elastic storage when ν < 0.16 (PNE-BI ↑ 21.3% at 3007.7 m), maintaining the transitional state, whereas depth effects accelerate ductility when ν ≥ 0.22 (PNE-BI = 0.314 at 3078.77 m). Unlike traditional multi-variable models (e.g., Table 1’s Drucker-Prager), PNE-BI requires only conventional-log-derived ν, bypassing complex integrals to provide real-time quantitative criteria for deep fracturing.

- (3)

- The synergy between rising confinement and increasing depth systematically reshapes energy evolution pathways (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). High confinement (>45 MPa) markedly suppresses brittle fracture, reducing elastic energy (S1) from 47.2% (68.89 MJ/m3) at 3007.7 m/0 MPa to 48.7% (147.70 MJ/m3) at the same depth under 75 MPa, while plastic (S2) and damage energies (S3) jointly account for substantial dissipation (S2 + S3 = 35.7% at 75 MPa). Depth effects amplified via rising dramatically intensify damage: under 0 MPa confinement, S3 energy surges 44-fold (from 0.7%/0.96 MJ/m3 at = 0.15 to 31.1%/10.86 MJ/m3 at = 0.22), exposing reduced microcrack initiation barriers due to deep clay hydration (Figure 10 red zones). Ultimately, dissipation paths exhibit depth-dependent transitions: shallow zones (3007.7 m) prioritize elastic storage; deep zones (3078.77 m) emphasize damage-plasticity under low confinement; and high confinement (75 MPa) shifts dominance to plastic dissipation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. China Mineral Resources Report 2016; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Suo, Y.; Wei, X.; Cao, W.; Pan, Z.; Hou, B.; Huang, B.; Li, Y. Review on specimen structure and bedding plane effects in mode-I fracture toughness testing of shale. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 328, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, G.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Deep shale gas exploration and development in the southern Sichuan Basin: New progress and challenges. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2023, 10, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Peng, S.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, H.; Ren, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, N.; Wu, J.; Song, Y.; Shen, C. Shale brittleness evaluation under high temperature and high confining stress based on energy evolution. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2025, 43, 989–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Handin, J. An application of high pressure in geophysics: Experimental rock deformation. Trans. ASME 1953, 75, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Guan, W.; Dong, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; He, W.; Fu, X.; Pan, Z.; Guo, B. Study on the heat extraction patterns of fractured hot dry rock reservoirs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 262, 125286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, H.; Zoback, M.D. Mechanical properties of shale-gas reservoir rocks—Part 1: Static and dynamic elastic properties and anisotropy. Geophysics 2013, 78, D381–D392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Han, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, X. Dynamic Mechanical Properties and Fracturing Behavior of Marble Specimens Containing Single and Double Flaws in SHPB Tests. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1623–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Song, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiao, H. Experimental Study on Influence of Loading Rate on Brittleness Indexes of Marble. J. Min. Sci. 2025, 61, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zuo, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, C. Criterion for residual strength and brittle-ductile transition of brittle rock under triaxial stress conditions. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pel, L.; You, Z.; Smeulders, D. Brittleness indices for chemically corroded rocks under unloading confining pressure. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 288, 110032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Jiang, C.; Yin, W.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Liu, Q. Experimental study on mechanical and damage characteristics of coal under true triaxial cyclic disturbance. Eng. Geol. 2021, 295, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcinovic, D.; Silva, M.A.G. Statistical aspect of the continuous damage theory. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1982, 18, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybacki, E.; Meier, T.; Dresen, G. What controls the mechanical properties of shale rocks?—Part II: Brittleness. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 158, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Su, X.H.; He, W.Y.; Fu, X.F.; Pan, Z.J. Fracability evaluation of sandstone-shale interbedded reservoir in Daqingzijing area, Songliao Basin. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2024, 43, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, J.C.; Cook, N.G.W.; Zimmerman, R.W. Fundamentals of Rock Mechanics, 4th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Raj, A.; Singh, B. Modified Mohr–Coulomb criterion for non-linear triaxial and polyaxial strength of jointed rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybacki, E.; Meier, T.; Dresen, G. What controls the mechanical properties of shale rocks?—Part I: Strength and Young’s modulus. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 144, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.C.; Prager, W. Soil mechanics and plastic analysis or limit design. Q. Appl. Math. 1952, 10, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A. Numerical simulation of progressive rock failure and associated seismicity. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997, 34, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre, J. A continuous damage mechanics model for ductile fracture. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1985, 107, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.G.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.J. Statistical damage model with strain softening and hardening for rocks under the influence of voids and volume changes. Can. Geotech. J. 2010, 47, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, W.G.; Su, Y.H. A statistical damage constitutive model for softening behavior of rocks. Eng. Geol. 2012, 143–144, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, J.X.; Jiang, Y. Mohr-Coulomb elastoplastic damage constitutive model for rocks and its principal stress implicit return mapping algorithm. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Gu, D.S. On a statistical damage constitutive model for rock materials. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. A unified hardening/softening elastoplastic model for rocks undergoing brittle-ductile transition with strength-mapping and fractional plastic flow rule. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 173, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.C.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, J.G.; Lu, Z.T.; Li, S.Y. A thermo-mechanical damage constitutive model for deep rock considering brittleness-ductility transition characteristics. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 2379–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, P.; Hu, K.; Zhao, L. Constitutive modeling of brittle–ductile transition in porous rocks: Formulation, identification and simulation. Acta Mech. 2023, 234, 2103–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Peng, L.; Liu, D.; Zuo, J. Microstructure effect of mechanical and cracking behaviors on brittle rocks using image-based fast Fourier transform method. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeim, B.; Javadzade Khiavi, A.; Khajavi, E.; Taghavi Khanghah, A.R.; Asgari, A.; Taghipour, R.; Bagheri, M. Machine Learning Approaches for Fatigue Life Prediction of Steel and Feature Importance Analyses. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.F.; Baud, P. The brittle-ductile transition in porous rock: A review. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 44, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadoullahtabar, S.R.; Asgari, A.; Tabari, M.M.R. Assessment, identifying, and presenting a plan for the stabilization of loessic soils exposed to scouring in the path of gas pipelines, case study: Maraveh-Tappeh city. Eng. Geol. 2024, 342, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafshgarkolaei, H.J.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M.A.; Mojtahedi, A. A modified orthonormal polynomial series expansion tailored to thin beams undergoing slamming loads. Ocean Eng. 2019, 182, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Method/Model | Equation/Key Features | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drucker-Prager | Drucker-Prager Elasto-Plastic Model | Captures plastic flow/yield under high confinement; lacks accuracy for brittle failure (e.g., microcrack growth, post-peak softening) at low pressure | [19] |

| Tang et al. | Statistical Meso-Damage Mechanics Model | Integrates statistical heterogeneity (Weibull) with damage mechanics to simulate progressive brittle fracture and crack propagation | [20] |

| Lemaitre | Continuum Damage Mechanics (CDM) | Tracks macroscale damage evolution based on effective stress; establishes the | [21] |

| Cao et al. | Statistical Damage-Void Model | Integrates void evolution and volume changes into statistical damage mechanics to simulate both strain softening and hardening behaviors. | [22] |

| Li et al. | Statistical Softening Damage Model | Incorporates damage thresholds and statistical distribution to accurately simulate the strain-softening behavior and failure evolution of rocks. | [23] |

| Cao Wengui et al. | Statistical Damage Model | Incorporates loading conditions and rock properties; extended to simulate void-compaction strain softening | [24] |

| Deng & Gu | MaxEnt Statistical Damage Model | Proposes the Maximum Entropy Distribution (instead of Weibull) to describe micro-element strength for more flexible damage prediction. | [25] |

| Tang et al. | Fractional Plasticity BDT Model | Utilizes strength-mapping and fractional plastic flow rules to capture strain hardening/softening and brittle-ductile transition. | [26] |

| Chen Liang et al. | Granite Damage-Plasticity Model | Models brittle-ductile behavior in deep granite | [27] |

| Liu H et al. | Damage-Plastic Work Coupling | Simulates concurrent damage accumulation and plastic flow under high pressure via energy dissipation | [28] |

| Zhang L et al. | Stiffness-Plasticity Coupling Model | Unifies brittle fracture and ductile flow using internal variables | [29] |

| Li et al. | Image-based FFT Micromechanical Model | Reconstructs heterogeneous microstructure via Digital Image Processing (DIP) and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to predict nonlinear cracking behaviors. | [30] |

| Wong & Baud | Micromechanical Failure Mechanism | Systematically differentiates brittle faulting (dilatancy) from cataclastic flow (pore collapse) to describe the brittle-ductile transition in porous rocks. | [31] |

| Sample ID (Depth) | Lithology | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Cohesion (MPa) | Internal Friction Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pingye-1 Well-3007.7 m | Interbedded mud-silt Siltstone | 38.98 | 0.15 | 71.5 | 25.98 |

| Pingye-1 Well-3029.9 m | Interbedded mud-silt | 43.71 | 0.16 | 47.50 | 30.44 |

| Pingye-1 Well-3078.77 m | Interbedded mud-silt | 34.21 | 0.22 | 26.70 | 34.46 |

| Range | Failure Mode | Brittle-Ductile State | Mechanical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.16 | Longitudinal splitting (Brittle-dominated) | Brittle Zone | Uniaxial residual strength ratio > 60% |

| 0.16 ≤ ≤ 0.20 | Conjugate shear (Transition) | Transition Zone | Strain hardening under confining pressure > 45 MPa |

| > 0.20 | Barreling deformation (Ductile-dominated) | Ductile Zone | Peak strain > 2.0% |

| Mechanical Quantity | Expression | Relationship with | Impact on Brittle-Ductile Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Modulus () | Reduced volumetric stiffness → Enhanced compressibility over brittle dilatancy | ||

| Dilatancy Tendency | Suppresses brittle crack propagation → Promotes energy dissipation via plastic flow |

| Core Sample Depth (m) | Confining Pressure (MPa) | S1 (MJ/m3) | S2 (MJ/m3) | S3 (MJ/m3) | S4 (MJ/m3) | Total Energy (MJ/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3007.7 | 0 | 68.89 | 9.06 | 0.96 | 65.85 | 145.77 |

| 3007.7 | 15 | 47.80 | 40.70 | 52.10 | 36.40 | 177.00 |

| 3007.7 | 45 | 125.40 | 33.90 | 42.90 | 83.30 | 285.60 |

| 3007.7 | 75 | 147.70 | 61.80 | 46.60 | 47.50 | 303.60 |

| 3029.9 | 0 | 41.30 | 0 | 40.40 | 1.90 | 83.70 |

| 3029.9 | 15 | 48.80 | 11.20 | 24.30 | 17.50 | 101.80 |

| 3029.9 | 45 | 48.00 | 12.00 | 24.30 | 17.30 | 101.50 |

| 3029.9 | 75 | 89.67 | 82.28 | 60.12 | 41.74 | 273.80 |

| 3078.77 | 0 | 14.76 | 7.41 | 10.86 | 1.94 | 34.96 |

| 3078.77 | 15 | 42.74 | 7.54 | 25.57 | 16.15 | 92.00 |

| 3078.77 | 45 | 40.69 | 9.74 | 25.56 | 15.52 | 91.52 |

| 3078.77 | 75 | 108.11 | 120.07 | 31.76 | 74.19 | 334.13 |

| Core Sample Depth (m) | Confining Pressure (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio ν | (MJ/m3) | (MJ/m3) | λ( ) | PNE-BI | PNE-BI Trend | Brittleness State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3007.7 | 0 | 0.15 | 68.89 | 74.91 | 0.971 | 0.479 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3007.7 | 15 | 0.15 | 47.80 | 77.10 | 0.971 | 0.390 | Distinct Ductility | Ductile Region |

| 3007.7 | 45 | 0.15 | 125.40 | 117.20 | 0.971 | 0.524 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3007.7 | 75 | 0.15 | 147.70 | 109.30 | 0.971 | 0.581 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3029.9 | 0 | 0.16 | 41.30 | 1.90 | 1.000 | 0.956 | High Brittleness | Brittle Region |

| 3029.9 | 15 | 0.16 | 48.80 | 28.70 | 1.000 | 0.630 | Moderate Brittleness | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3029.9 | 45 | 0.16 | 48.00 | 29.30 | 1.000 | 0.621 | Moderate Brittleness | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3029.9 | 75 | 0.16 | 89.67 | 124.02 | 1.000 | 0.420 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3078.77 | 0 | 0.22 | 14.76 | 9.35 | 1.214 | 0.565 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3078.77 | 15 | 0.22 | 42.74 | 23.69 | 1.214 | 0.599 | Moderate Brittleness | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3078.77 | 45 | 0.22 | 40.69 | 25.26 | 1.214 | 0.572 | Brittle-Ductile Transition | Brittle-Ductile Transition Region |

| 3078.77 | 75 | 0.22 | 108.11 | 194.26 | 1.214 | 0.314 | Distinct Ductility | Ductile Region |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, B.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Feng, J.; Shao, H.; Liu, L.; Cao, X.; Wang, T.; Zhao, J. Poisson’s Ratio as the Master Variable: A Single-Parameter Energy-Conscious Model (PNE-BI) for Diagnosing Brittle–Ductile Transition in Deep Shales. Sustainability 2026, 18, 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020985

Gao B, Wang J, Li B, Li J, Feng J, Shao H, Liu L, Cao X, Wang T, Zhao J. Poisson’s Ratio as the Master Variable: A Single-Parameter Energy-Conscious Model (PNE-BI) for Diagnosing Brittle–Ductile Transition in Deep Shales. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020985

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Bo, Jiping Wang, Binhui Li, Junhui Li, Jun Feng, Hongmei Shao, Lu Liu, Xi Cao, Tangyu Wang, and Junli Zhao. 2026. "Poisson’s Ratio as the Master Variable: A Single-Parameter Energy-Conscious Model (PNE-BI) for Diagnosing Brittle–Ductile Transition in Deep Shales" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020985

APA StyleGao, B., Wang, J., Li, B., Li, J., Feng, J., Shao, H., Liu, L., Cao, X., Wang, T., & Zhao, J. (2026). Poisson’s Ratio as the Master Variable: A Single-Parameter Energy-Conscious Model (PNE-BI) for Diagnosing Brittle–Ductile Transition in Deep Shales. Sustainability, 18(2), 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020985