Energy Transitions in the Digital Economy: Interlinking Supply Chain Innovation, Growth, and Policy Stringency in OECD Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Method

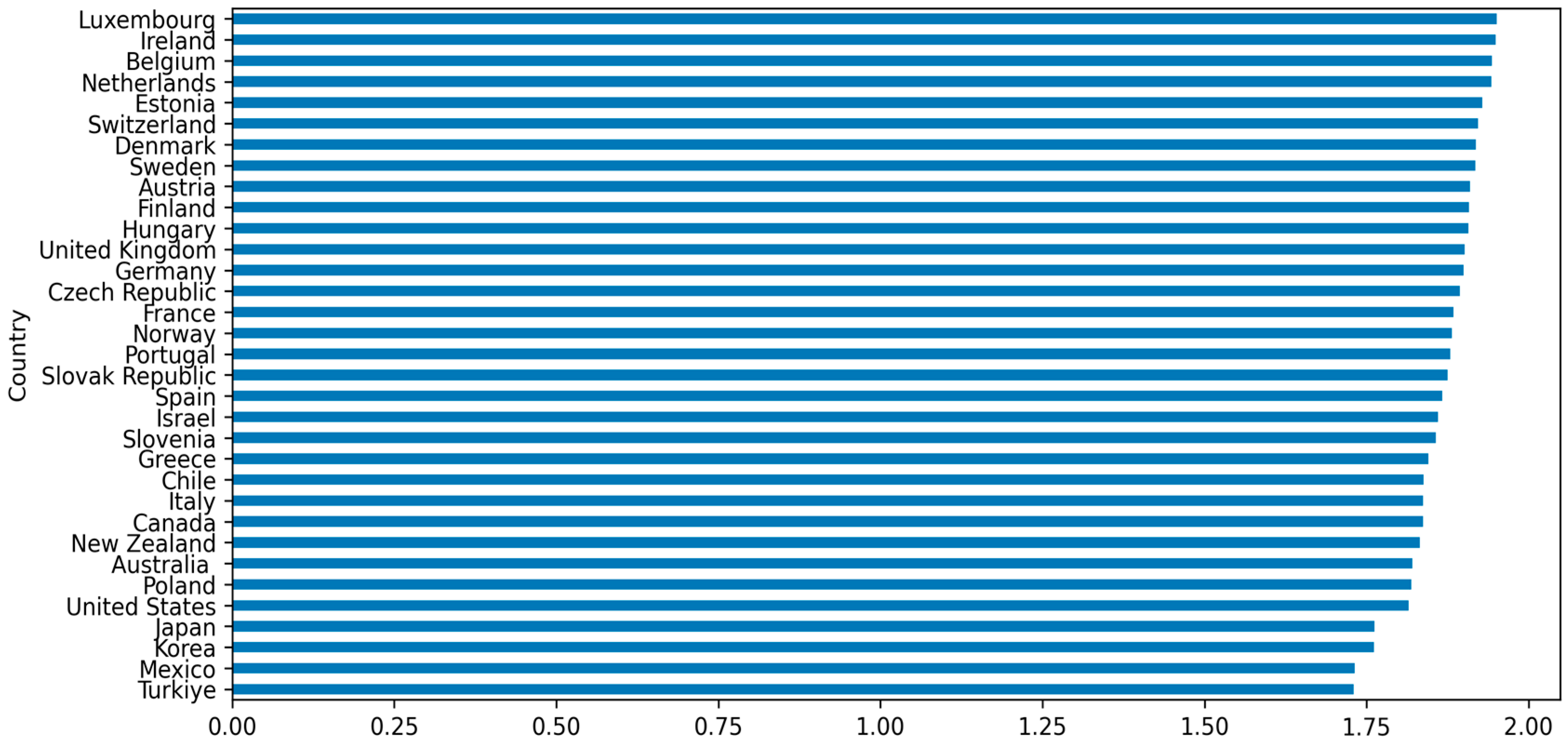

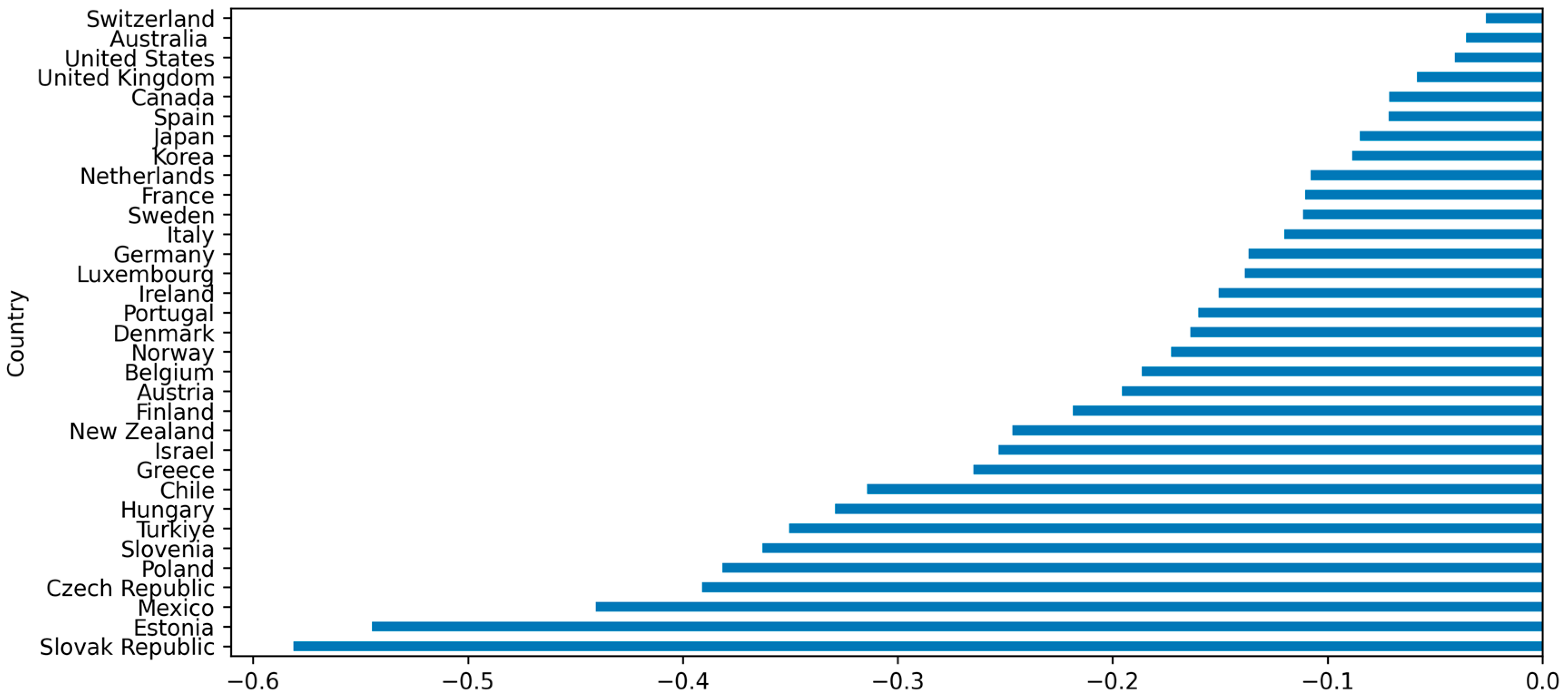

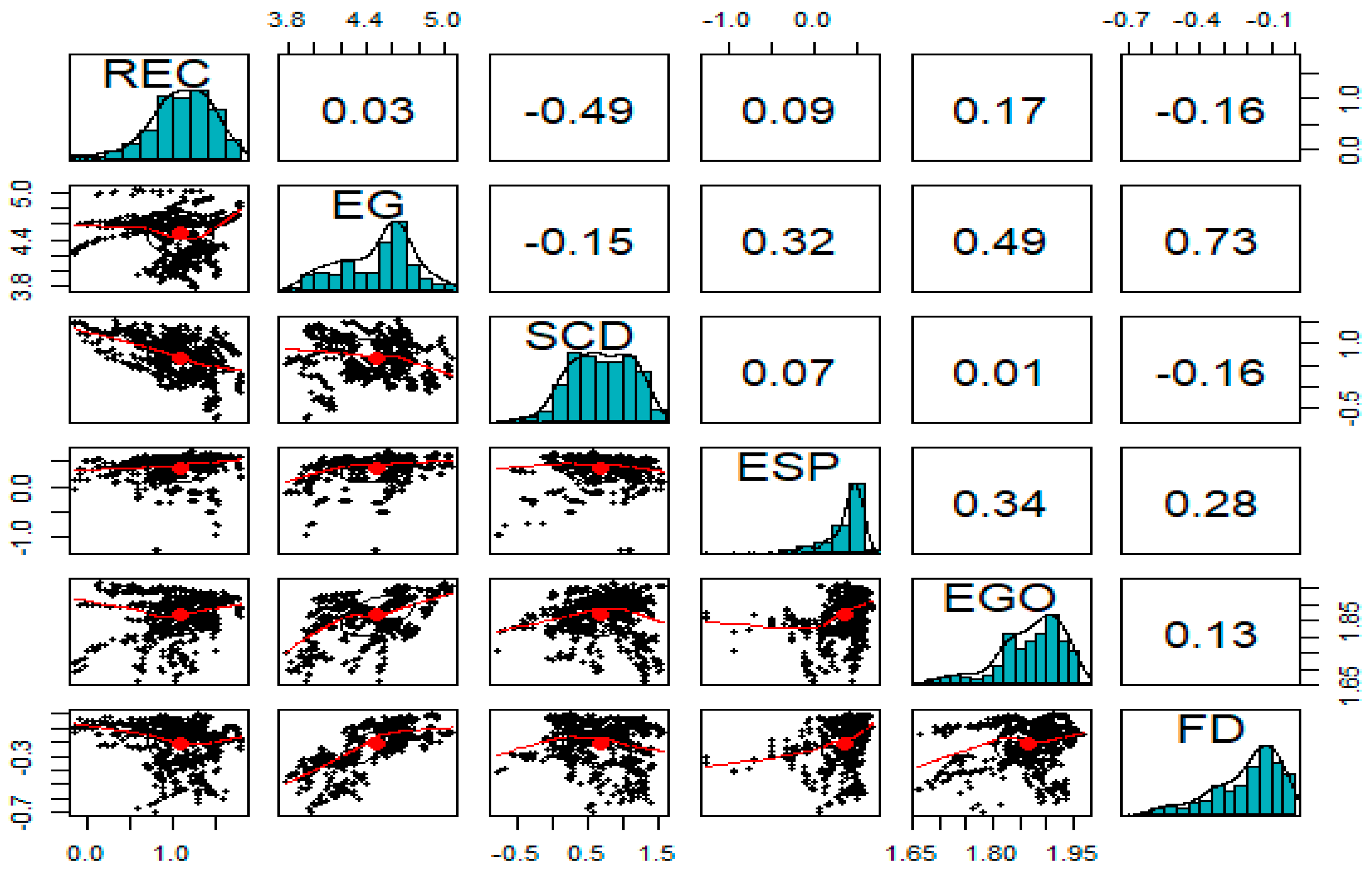

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Model Specification

3.3. Econometric Estimation Strategy

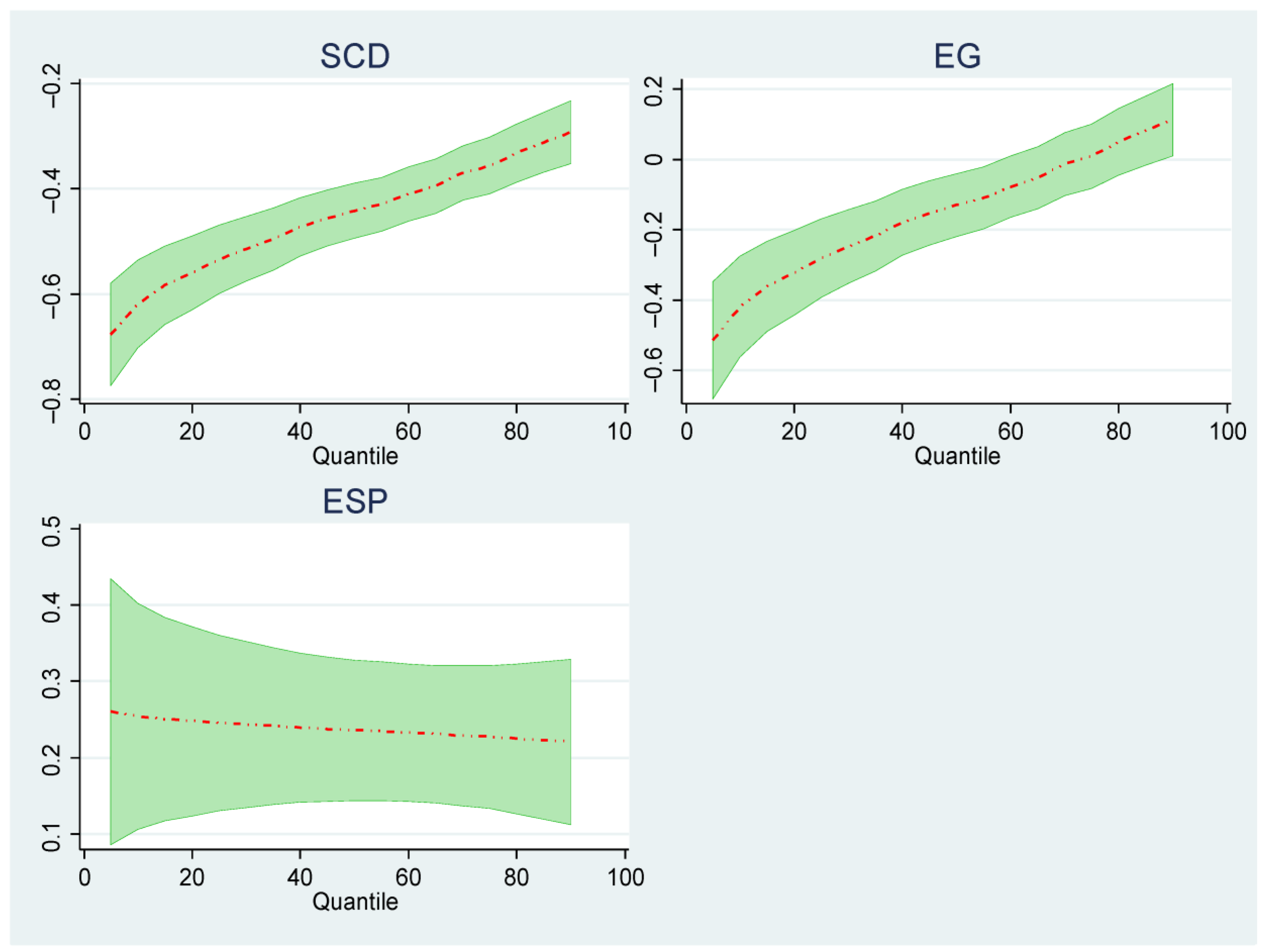

4. Presentation and Discussions

4.1. CSD Analysis

4.2. Unit Root Test Analysis

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| REC | Renewable Energy Consumption |

| SCD | Supply Chain Digitalization |

| ESP | Environmental Stringency Policy |

| EG | Economic Growth |

| EGO | Economic Globalization |

| FD | Financial Development |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| MMQR | Method of Moments Quantile Regression |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| EKC | Environmental Kuznets Curve |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| CO2 | Carbon Emissions |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| AMG | Augmented Mean Group |

| FMOLS | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares |

| DCCE | Dynamic Common Correlated Effects |

References

- Can, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Mercan, M.; Kalugina, O.A. The role of trading environment-friendly goods in environmental sustainability: Does green openness matter for OECD countries? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zafar, M.W.; Usman, M.; Kalugina, O.A.; Khan, I. Internalizing negative environmental externalities through environmental technologies: The contribution of renewable energy in OECD countries. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Yi, B. Sustainable development and supply chain management in renewable-based community based self-sufficient utility: An analytical review of social and environmental impacts and trade-offs in digital twin. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 65, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedghorban, Z.; Tahernejad, H.; Meriton, R.; Graham, G. Supply chain digitalization: Past, present and future. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Trevisan, A.H.; Yang, M.; Mascarenhas, J. A framework of digital technologies for the circular economy: Digital functions and mechanisms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 2171–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Uzun, B. Sustainability Under Uncertainty: A Time-Frequency Perspective on Brazil’s Nuclear Energy Pathway, Digital Evolution, and Financial Risk Exposure. Geol. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamreklidze, E. Cyber security in developing countries, a digital divide issue: The case of Georgia. J. Int. Commun. 2014, 20, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Taiwo, T.S.; Uzun, B. Consolidating sustainable development in G7 economies: The role of green production process, energy transition, environmental policy stringency, and economic globalization. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2025, 33, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Hu, X.; Alnafisah, H.; Zeast, S.; Akhtar, M.R. Enhancing climate action in OECD countries: The role of environmental policy stringency for energy transitioning to a sustainable environment. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Luo, R.; Nadeem, M.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Advancing sustainable growth and energy transition in the United States through the lens of green energy innovations, natural resources and environmental policy. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shinwari, R.; Zhao, S.; Dagestani, A.A. Energy transition, geopolitical risk, and natural resources extraction: A novel perspective of energy transition and resources extraction. Resour. Policy 2023, 83, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadov, A.K.; van der Borg, C. Do natural resources impede renewable energy production in the EU? A mixed-methods analysis. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingru, L.; Onifade, S.T.; Ramzan, M.; AL-Faryan, M.A.S. Environmental perspectives on the impacts of trade and natural resources on renewable energy utilization in Sub-Sahara Africa: Accounting for FDI, income, and urbanization trends. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.Y.; Sadiq, M.; Chien, F. The role of natural resources and eco-financing in producing renewable energy and carbon neutrality: Evidence from ten Asian countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zakari, A.; Youn, I.J.; Tawiah, V. The impact of natural resources on renewable energy consumption. Resour. Policy 2023, 83, 103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.Z.; Doğan, B.; Husain, S.; Huang, S.; Shahzad, U. Role of economic complexity to induce renewable energy: Contextual evidence from G7 and E7 countries. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.; Ahmed, Z. Towards sustainable development in the European Union countries: Does economic complexity affect renewable and non-renewable energy consumption? Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B.; Nguyen, N.H.; Shahbaz, M. Energy security as new determinant of renewable energy: The role of economic complexity in top energy users. Energy 2023, 263, 125799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K. The role of energy security and economic complexity in renewable energy development: Evidence from G7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 56073–56093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.B.; Kenku, O.T.; Oliyide, J.A.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S.; Ogunjemilua, O.D. Does economic complexity drive energy efficiency and renewable energy transition? Energy 2023, 278, 127712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, G.; Afshan, S.; Awosusi, A.A.; Abbas, S. Transition towards sustainable energy: The role of economic complexity, financial liberalization and natural resources management in China. Resour. Policy 2023, 83, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Demir, E.; Padhan, H. The impact of economic globalization on renewable energy in the OECD countries. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, H.; Padhang, P.C.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ahmed, R.; Hammoudeh, S. Renewable energy consumption and robust globalization(s) in OECD countries: Do oil, carbon emissions and economic activity matter? Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 32, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Raghutla, C.; Chittedi, K.R.; Fareed, Z. How economic policy uncertainty and financial development contribute to renewable energy consumption? The importance of economic globalization. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Rjoub, H.; Dördüncü, H.; Kirikkaleli, D. Does the potency of economic globalization and political instability reshape renewable energy usage in the face of environmental degradation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 22686–22701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayale, N.; Ali, E.; Tchagnao, A.-F.; Nakumuryango, A. Determinants of renewable energy production in WAEMU countries: New empirical insights and policy implications. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Determinants of renewable energy consumption: Importance of democratic institutions. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ahmad, M.; Ali, S. The impact of trade, environmental degradation and governance on renewable energy consumption: Evidence from selected ASEAN countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, B.M.; Taspinar, N.; Gokmenoglu, K.K. The impact of financial development and economic growth on renewable energy consumption: Empirical analysis of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 663, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, G. Analyzing the impacts of economic growth, pollution, technological innovation and trade on renewable energy production in selected Latin American countries. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-H.; Huang, C.-M.; Lee, M.-C. Threshold effect of the economic growth rate on the renewable energy development from a change in energy price: Evidence from OECD countries. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 5796–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Nasreen, S.; Anwar, M.A. Impact of equity market development on renewable energy consumption: Do the role of FDI, trade openness and economic growth matter in Asian economies? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 130244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Lee, H. The role of energy prices and economic growth in renewable energy capacity expansion—Evidence from OECD Europe. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- World Bank GDP per Capita (Constant 2015 US$)|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- OECD. Measuring Environmental Policy Stringency in OECD Countries: An Update of the OECD Composite EPS Indicator; OECD Economics Department Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; Volume 1703. [Google Scholar]

- KOF. KOF Globalisation Index. Available online: https://kof.ethz.ch/en/forecasts-and-indicators/indicators/kof-globalisation-index.html (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Salahuddin, M.; Alam, K. Information and Communication Technology, electricity consumption and economic growth in OECD countries: A panel data analysis. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 76, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H. Is what we think of as “rebound” really just income effects in disguise? Energy Policy 2013, 57, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Jevons’ Paradox revisited: The evidence for backfire from improved energy efficiency. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1456–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Rjoub, H.; Ağa, M.; Onyenegecha, I.P. An insight into the asymmetric effect of economic globalization on renewable energy in Australia: Evidence from the nonlinear ARDL approach and wavelet coherence. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 3600–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godawska, J.; Wyrobek, J. The Impact of Environmental Policy Stringency on Renewable Energy Production in the Visegrad Group Countries. Energies 2021, 14, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsagr, N. How environmental policy stringency affects renewable energy investment? Implications for green investment horizons. Util. Policy 2023, 83, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphus, J.; Arminen, H.; Pekkanen, T.-L. The effect of institutions on clean energy investments and environmental degradation across income groups: Evidence based on the Method of Moments Quantile estimation. Energy 2025, 324, 136018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.; Silva, J.S. Quantiles via moments. J. Econom. 2019, 213, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels. Empir. Econ. 2021, 60, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Pohl, J.; Santarius, T. Digitalization and energy consumption. Does ICT reduce energy demand? Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhou, Y. Role of supply chain disruptions and digitalization on renewable energy innovation: Evidence from G7 nations. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirikkaleli, D.; Adebayo, T.S. Political risk and environmental quality in Brazil: Role of green finance and green innovation. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, A.-M.; Kistemann, T.; Dehbi, Y.; Kötter, T. (Un)just Distribution of Visible Green Spaces? A Socio-Economic Window View Analysis on Residential Buildings: The City of Cologne as Case Study. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 2025, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Rong, Z.; Ji, Q. Green innovation and firm performance: Evidence from listed companies in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Signs | Names of Variables | Measurements Unit | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

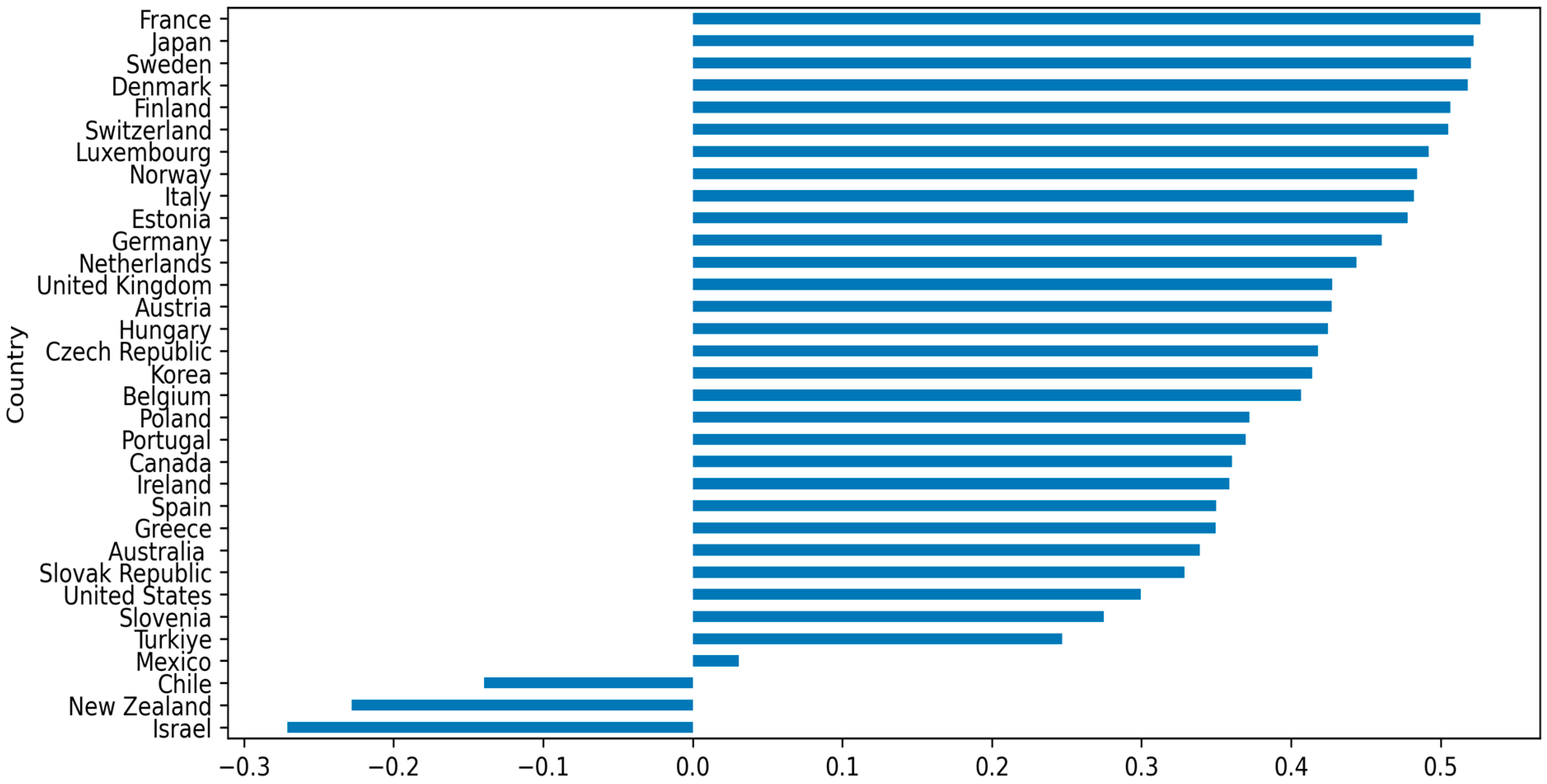

| REC | Renewable energy consumption | percentage of total final energy consumption | [34] |

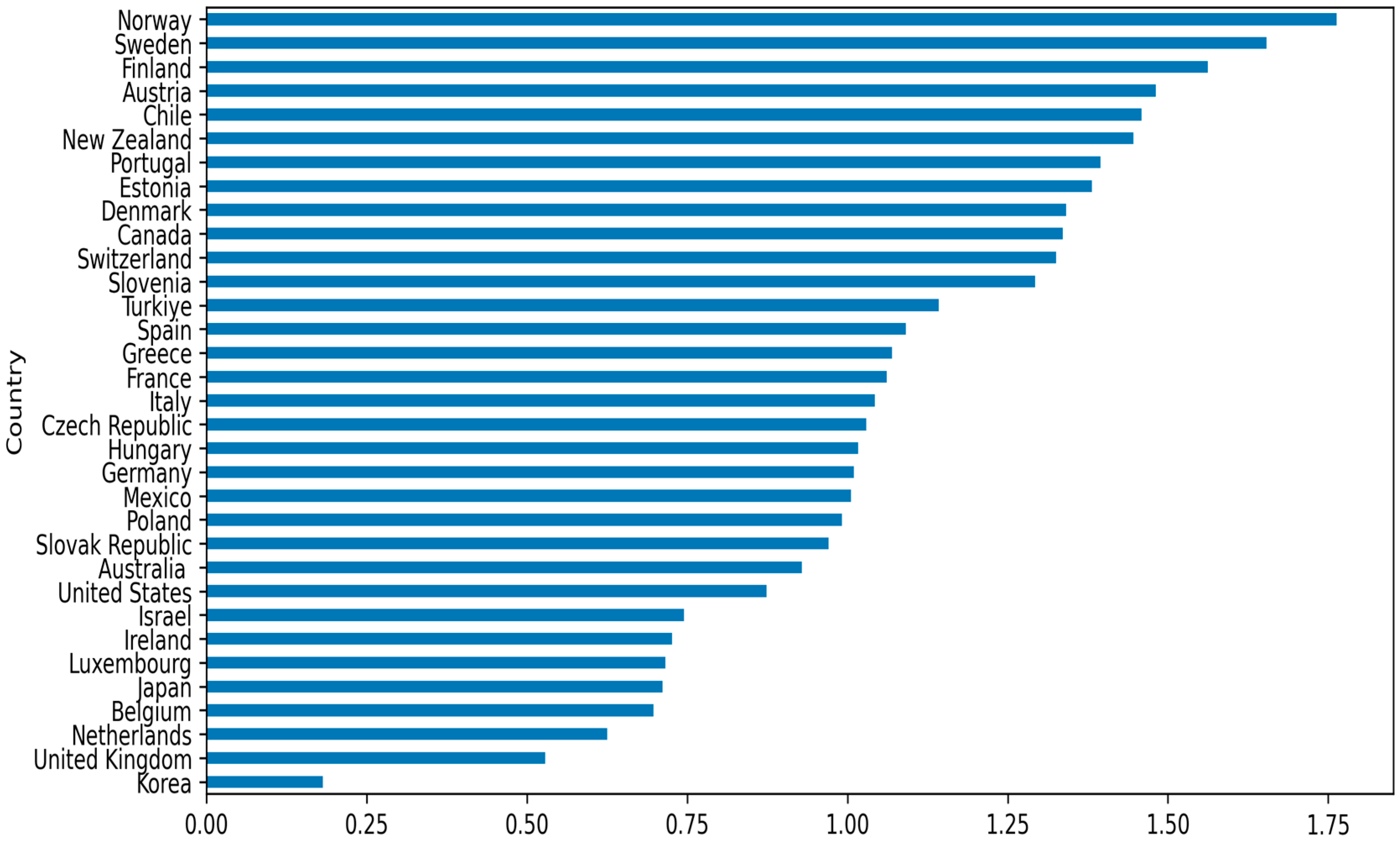

| SCD | Supply chain digitalization | ICT goods exports (% of total goods exports) | [34] |

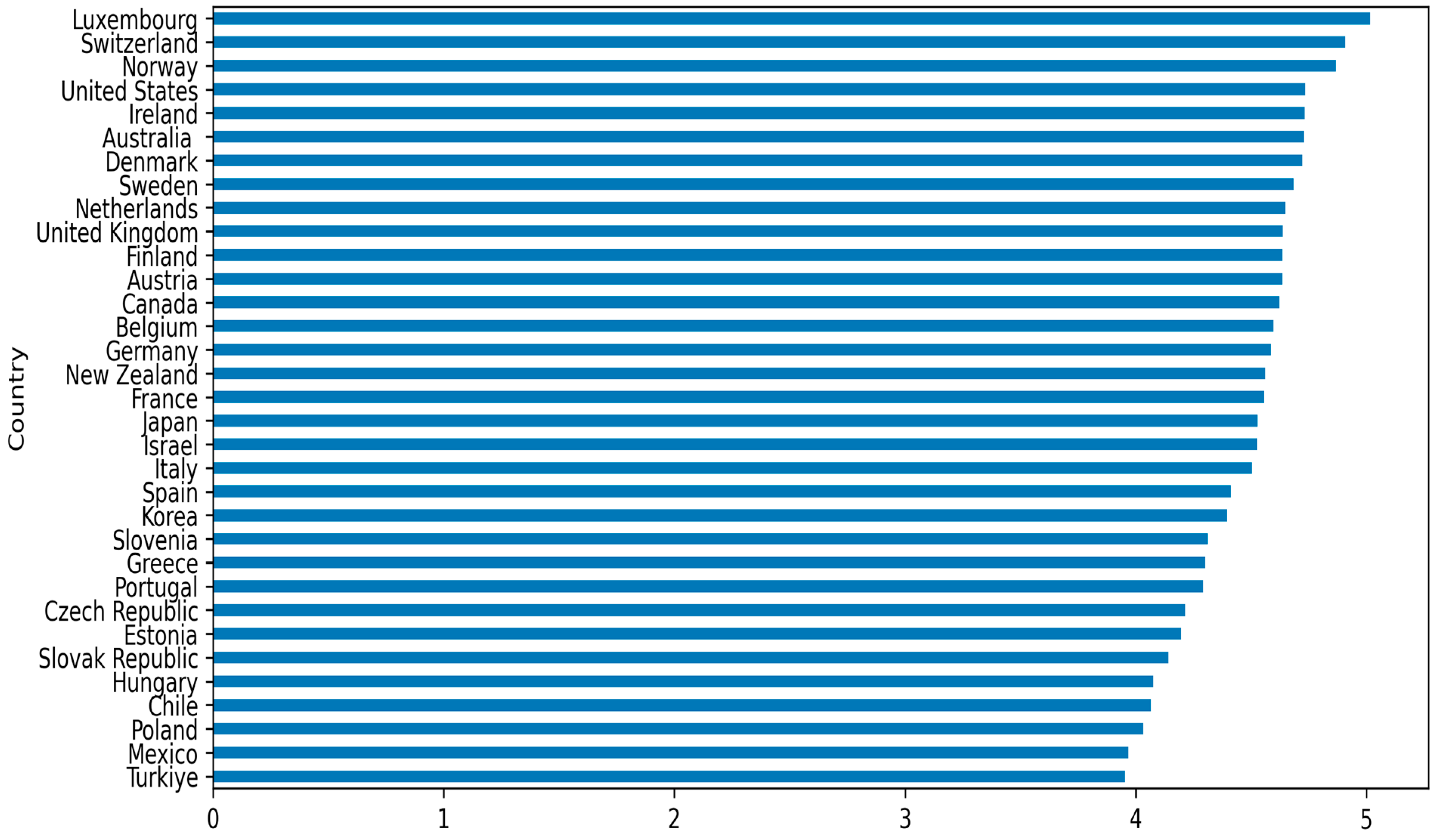

| EG | Economic growth | GDP per capita (Constant 2015 US$) | [35] |

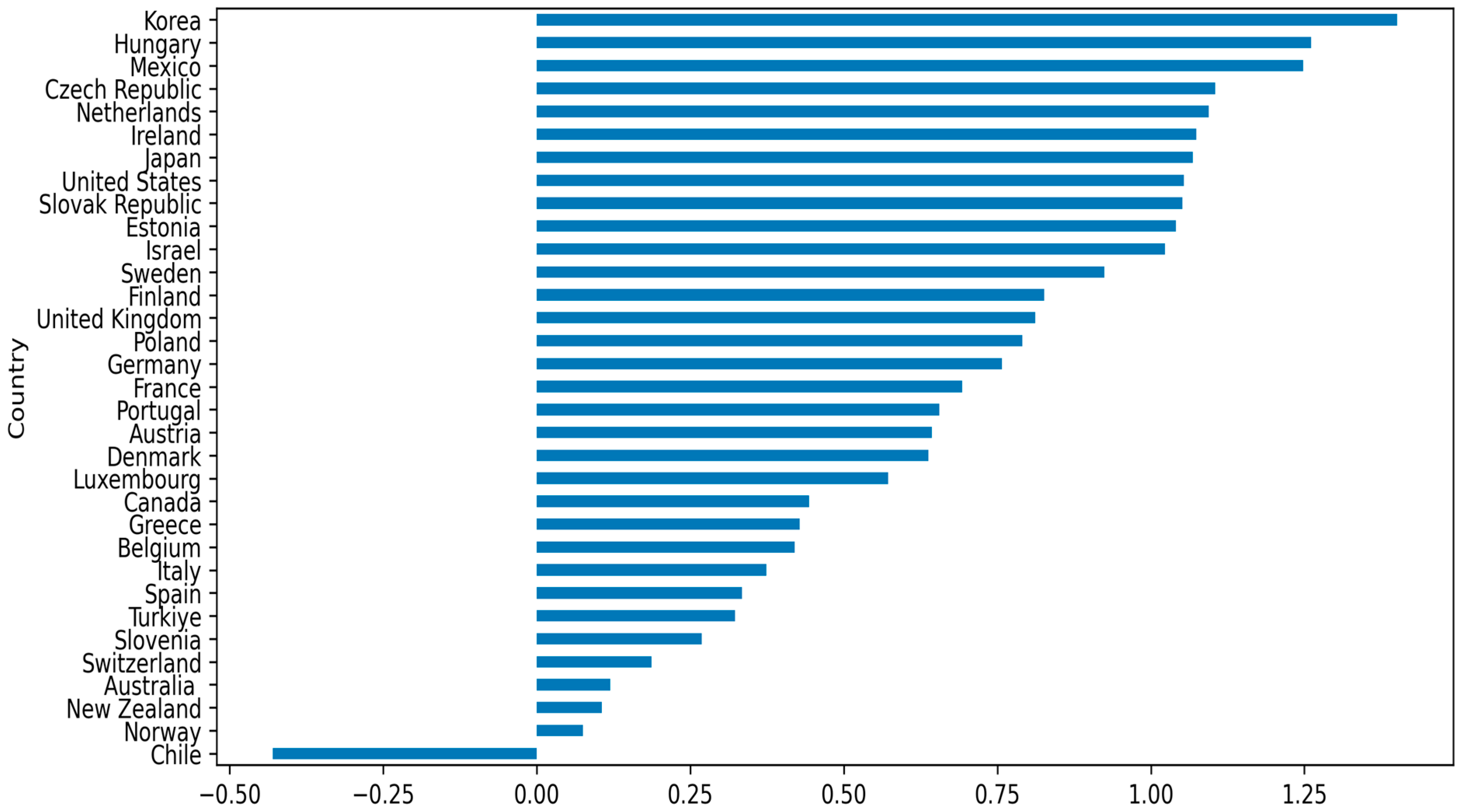

| ESP | Environmental stringency policy | Index | [36] |

| EGO | Economic globalization | Index | [37] |

| FD | Financial development | Index | International Monetary Fund Database |

| Variable | Level | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC | Overall | 1.078 | 0.388 | −0.154 | 1.788 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.352 | 0.181 | 1.763 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.174 | 0.453 | 1.683 | T = 22 | ||

| EG | Overall | 4.478 | 0.281 | 3.777 | 5.050 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.280 | 3.953 | 5.016 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.051 | 4.280 | 4.694 | T = 22 | ||

| SCD | Overall | 0.678 | 0.450 | −0.795 | 1.562 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.421 | −0.429 | 1.400 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.174 | 0.089 | 1.259 | T = 22 | ||

| ESP | Overall | 0.348 | 0.268 | −1.255 | 0.689 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.206 | −0.271 | 0.526 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.174 | −0.635 | 0.794 | T = 22 | ||

| EGO | Overall | 1.867 | 0.063 | 1.661 | 1.968 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.060 | 1.730 | 1.950 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.020 | 1.742 | 1.934 | T = 22 | ||

| FD | Overall | −0.209 | 0.148 | −0.699 | −0.001 | N = 726 |

| Between | 0.146 | −0.581 | −0.026 | n = 33 | ||

| Within | 0.036 | −0.387 | −0.103 | T = 22 |

| Variable | CSD Test | p-Value | Corr | Abs (Corr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC | 57.82 * | 0.000 | 0.537 | 0.763 |

| SCD | 41.75 * | 0.000 | 0.388 | 0.665 |

| ESP | 88.89 * | 0.000 | 0.826 | 0.826 |

| EG | 77.42 * | 0.000 | 0.719 | 0.807 |

| EGO | 31.52 * | 0.000 | 0.293 | 0.494 |

| FD | 30.66 * | 0.000 | 0.285 | 0.422 |

| Variable | CIPS | CADF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (0) | I (1) | I (0) | I (1) | |

| REC | −2.390 | −4.727 * | −2.630 | −5.035 * |

| SCD | −2.348 | −4.132 * | −2.520 | −4.211 * |

| ESP | −2.911 | −4.771 * | −3.073 | −4.721 * |

| EG | −1.495 | −3.199 * | −1.670 | −3.417 * |

| EGO | −2.269 | −4.445 * | −2.493 | −4.673 * |

| FD | −2.257 | −5.212 * | −3.457 | −5.277 * |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | |

| Modified variance ratio | −5.219 * | 0.000 | −6.180 * | 0.000 |

| Modified Phillips–Perron t | 2.1290 ** | 0.016 | 3.976 * | 0.0000 |

| Phillips–Perron t | 0.364 | 0.357 | −0.010 | 0.495 |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | 1.023 | 0.153 | 0.481 | 0.315 |

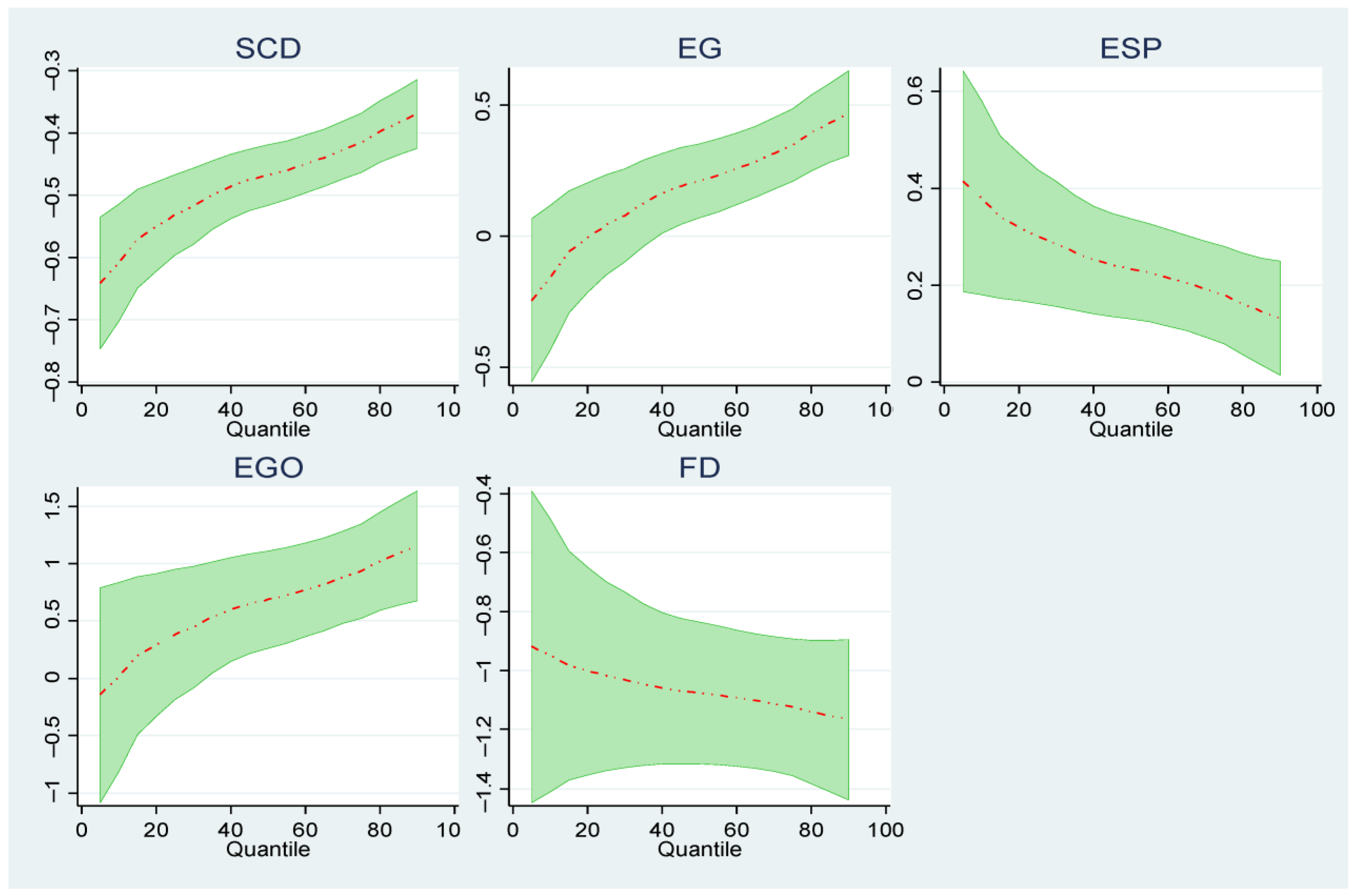

| Variables | Location | Scale | Quantiles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ = 0.10 | τ = 0.20 | τ = 0.30 | τ = 0.40 | τ = 0.50 | τ = 0.60 | τ = 0.70 | τ = 0.80 | τ = 0.90 | |||

| SCD | −0.447 * [−16.89] | 0.100 * [6.46] | −0.620 * [14.50] | −0.560 * [−15.62] | −0.515 * [−16.43] | −0.472 * [−16.75] | −0.442 * [−16.63] | −0.409 * [−15.64] | −0.369 * [−13.88] | −0.332 * [−11.80] | −0.291 * [−9.54] |

| EG | −0.137 * [−3.04] | 0.161 * [6.05] | −0.415 * [−5.87] | −0.318 * [−5.20] | −0.246 * [−4.59] | −0.178 * [−3.69] | −0.129 * [−2.84] | −0.077 *** [−1.73] | −0.013 [−0.29] | 0.046 [0.97] | 0.112 ** [2.14] |

| ESP | 0.236 * [4.99] | −0.011 [−0.40] | 0.255 * [3.38] | 0.249 * [3.94] | 0.244 * [4.41] | 0.239 * [4.82] | 0.236 * [5.02] | 0.232 * [5.08] | 0.228 * [4.89] | 0.224 * [4.50] | 0.219 * [3.98] |

| Constant | 1.917 * [9.75] | −0.524 * [−4.54] | 2.818 * [8.93] | 2.504 * [9.48] | 2.269 * [9.82] | 2.048 * [9.86] | 1.889 * [9.63] | 1.720 * [8.94] | 1.512 * [7.72] | 1.317 * [6.34] | 1.105 * [4.87] |

| N | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 |

| Variables | Location | Scale | Quantiles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ = 0.10 | τ = 0.20 | τ = 0.30 | τ = 0.40 | τ = 0.50 | τ = 0.60 | τ = 0.70 | τ = 0.80 | τ = 0.90 | |||

| SCD | −0.473 * [−18.78] | 0.070 * [4.29] | −0.610 * [−12.74] | −0.551 * [−15.19] | −0.517 * [−16.71] | −0.485 * [−18.28] | −0.467 * [−18.97] | −0.449 * [−18.93] | −0.426 * [−17.92] | −0.396 * [−15.71] | −0.367 * [−13.08] |

| EG | 0.195 * [2.63] | 0.180 * [3.75] | −0.156 [−1.11] | −0.004 [−0.04] | 0.081 [0.89] | 0.164 ** [2.11] | 0.211 * [2.91] | 0.257 * [3.69] | 0.316 * [4.54] | 0.394 * [5.32] | 0.468 * [5.67] |

| ESP | 0.240 * [4.45] | −0.072 ** [−2.07] | 0.382 * [3.75] | 0.321 * [4.14] | 0.286 * [4.35] | 0.252 * [4.46] | 0.234 * [4.42] | 0.215 [4.24] | 0.191 * [3.80] | 0.160 * [2.99] | 0.130 ** [2.17] |

| EGO | 0.656 * [2.96] | 0.329 ** [2.29] | 0.016 [0.04] | 0.292 [0.92] | 0.448 *** [1.66] | 0.601 * [2.59] | 0.686 * [3.16] | 0.770 * [3.69] | 0.878 * [4.24] | 1.019 * [4.63] | 1.154 * [4.69] |

| FD | −1.071 * [−8.57] | −0.063 [−0.78] | −0.947 * [−4.03] | −1.001 * [−5.59] | −1.031 * [−6.79] | −1.060 * [−8.11] | −1.076 * [−8.80] | −1.093 * [−9.31] | −1.113 [−9.59] | −1.140 * [−9.24] | −1.167 * [−8.42] |

| Constant | −1.007 [2.71] | −1.224 [−5.07] | 1.371 [1.93] | 0.343 [0.64] | −0.235 [−0.51] | −0.802 [−2.04] | −1.118 [−3.08] | −1.430 [−4.08] | −1.832 [−5.18] | −2.355 [−6.29] | −2.859 [−6.89] |

| N | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 | 726 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hashim, M.; Ojekemi, O.S. Energy Transitions in the Digital Economy: Interlinking Supply Chain Innovation, Growth, and Policy Stringency in OECD Countries. Sustainability 2026, 18, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020981

Hashim M, Ojekemi OS. Energy Transitions in the Digital Economy: Interlinking Supply Chain Innovation, Growth, and Policy Stringency in OECD Countries. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020981

Chicago/Turabian StyleHashim, Majdi, and Opeoluwa Seun Ojekemi. 2026. "Energy Transitions in the Digital Economy: Interlinking Supply Chain Innovation, Growth, and Policy Stringency in OECD Countries" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020981

APA StyleHashim, M., & Ojekemi, O. S. (2026). Energy Transitions in the Digital Economy: Interlinking Supply Chain Innovation, Growth, and Policy Stringency in OECD Countries. Sustainability, 18(2), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020981