Consumer Attitudes, Buying Behaviour, and Sustainability Concerns Toward Fresh Pork: Insights from the Black Slavonian Pig

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainability Concerns in Pig Farming

1.2. Consumer Preferences and Market Potential for Sustainable Meat

- What are the key dimensions of consumer pork-purchasing attitudes?

- What distinct consumer segments exist based on these dimensions?

- What demographic and behavioural factors predict segment membership?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development and Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Consumer Perceptions of Fresh Pork from the Black Slavonian Pig: Purchasing and Sustainability Concerns

3.3. Consumer Perspectives on Fresh Black Slavonian Pig Pork: Segmentation and Predictive Analysis of Buying Behaviour and Sustainability Concerns

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Consumers’ Attitudes

4.2. Consumers’ Segments

4.3. Predictors of Consumer Segment Membership

4.4. Impact on Policy Makers, Retailers, and Producers

4.4.1. Policy Recommendations

4.4.2. Retail and Producer Strategies

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable diets and biodiversity: Directions and solutions for policy, research and action. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium on Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity: Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action (No. RESEARCH), Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i3004e/i3004e00.htm (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Viti, D. Consumers’ Purchasing Intentions on the Legume Market as Evidence of Sustainable Behaviour. Agriculture 2020, 10, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Dutra de Barcellos, M.; Kügler, J.O.; Verbeke, W.; Grunert, K.G. Attitudes of European citizens towards pig production systems. Livest. Sci. 2009, 126, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Boekhorst, L.J.S.; Oosting, S.J.; Sørensen, J.T. Socio-cultural sustainability of pig production: Citizen perceptions in the Netherlands and Denmark. Livest. Sci. 2011, 140, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budimir, K.; Margeta, V.; Kralik, G.; Margeta, P. Silvopastoral keeping of the Black Slavonian Pigs. Krmiva Časopis o Hranidbi Zivotinj. Proizv. i Tehnol. Krme 2013, 55, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Senčić, Đ.; Samac, D. Preserving biodiversity of Black Slavonian pigs through production and evaluation of traditional meat products. Poljoprivreda 2017, 23, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, A.; Walenia, A. Native Pig Breeds as a Source of Biodiversity—Breeding and Economic Aspects. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, S.; Ribani, A.; Muñoz, M.; Alves, E.; Araujo, J.P.; Bozzi, R.; Candek-Potokar, M.; Charneca, R.; Di Palma, F.; Etherington, G.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing of European autochthonous and commercial pig breeds allows the detection of signatures of selection for adaptation of genetic resources to different breeding and production systems. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2020, 52, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, B.; Ferenčaković, M.; Šalamon, D.; Čačić, M.; Orehovački, V.; Iacolina, L.; Curik, I.; Cubric-Curik, V. Conservation Genomic Analysis of the Croatian Indigenous Black Slavonian and Turopolje Pig Breeds. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kušec, G.; Komlenić, M.; Gvozdanović, K.; Sili, V.; Krvavica, M.; Radišić, Ž.; Kušec, I.D. Carcass Composition and Physicochemical Characteristics of Meat from Pork Chains Based on Native and Hybrid Pigs. Processes 2022, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić Milković, S.; Lončarić, R.; Kralik, I.; Kristić, J.; Crnčan, A.; Djurkin Kušec, I.; Canavari, M. Consumers’ Preference for the Consumption of the Fresh Black Slavonian Pig’s Meat. Foods 2023, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić Milković, S.; Crnčan, A.; Kristić, J.; Kralik, I.; Djurkin Kušec, I.; Gvozdanović, K.; Kušec, G.; Kralik, Z.; Lončarić, R. Consumer Preferences for Cured Meat Products from the Autochthonous Black Slavonian Pig. Foods 2023, 12, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M. Utilizing Indigenous Animal Genetic Resources—Based on Research into Indigenous Cattle Breeds in the Basque Country in Northern Spain and Indigenous Pig Breeds in Vietnam. Anim. Sci. J. 2025, 96, E70046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerjak, M.; Faletar, I.; Šmit, G.; Ivanković, A. Breeding Motives and Attitudes Towards Stakeholders: Implications for the Sustainability of Local Croatian Breeds. Agriculture 2025, 15, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato d Nassivera, F.; Bujgatti, M.; Torquati, B. Consumers Demand for Social Farming Products: An Analysis with Discrete Choice Experiments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, S.; Arvidsson Segerkvist, K.; Wallgren, T.; Hansson, H.; Sonesson, U. A Systematic Mapping of Research on Sustainability Dimensions at Farm-level in Pig Production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Van der Werf, H.M.G. Perception of the environmental impacts of current and alternative modes of pig production by stakeholder groups. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Vitale, M.; Gil, J.M. Health Innovation in Patty Products. The Role of Food Neophobia in Consumers’ Non-Hypothetical Willingness to Pay, Purchase Intention and Hedonic Evaluation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čandek-Potokar, M.; Fontanesi, L.; Lebret, B.; Gil, J.H.; Ovilo, C.; Nieto, R.; Fernandez, A.; Pugliese, C.; Oliver, M.A.; Bozzi, R. Introductory Chapter: Concept and Ambition of Project TREASURE. In European Local Pig Breeds—Diversity and Performance. A Study of Project TREASURE; Intechopen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marsoner, T.; Vigl, L.E.; Manck, F.; Jaritz, G.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. Indigenous livestock breeds as indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A spatial analysis within the Alpine Space. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, C.; Sirtori, F. Quality of meat and meat products produced from southern European pig breeds. Meat Sci. 2012, 9, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, G. Consumers’ perception of farm animal welfare: An Italian and European perspective. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljenstolpe, C. Valuing animal welfare with choice experiments: An application to Swedish pig production. In Proceedings of the 11th Congress of the EAAE (European Association of Agricultural Economists), Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–27 August 2005; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Segmentation based on consumers’ perceived importance and attitude toward farm animal welfare. Int. J. Sociol. Food Agric. 2007, 15, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasevic, I.; Bahelka, I.; Ćitek, J.; Čandek-Potokar, M.; Djekić, I.; Getya, A.; Guerrero, L.; Ivanova, S.; Kušec, G.; Nakov, D.; et al. Attitudes and Beliefs of Eastern European Consumers Towards Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebig, D.G.; Keane, M.P.; Louviere, J.; Wasi, N. The Generalised Multinomial Logit Model: Accounting for Scale and Coefficient Heterogeneity. Mark. Sci. 2010, 29, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, L.E.; Bennett, R.M.; Tranter, R.B.; Wooldridge, M.J. Consumption of welfare-friendly food products in Great Britain, Italy and Sweden, and how it may be influenced by consumer attitudes to, and behaviour towards, animal welfare attributes. Int. J. Sociol. Food Agric. 2007, 15, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerwagen, L.R.; Mørkbak, M.R.; Denver, S.; Sandøe, P.; Christensen, T. The Role of Quality Labels in Market-Driven Animal Welfare. Agric Environ. Ethics 2014, 28, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Stakeholder, citizen, and consumer interests in farm animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2009, 18, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawse, J. Consumer attitudes towards farm animals and their welfare: A pig production case study. Biosci. Horiz. 2010, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Curry Raper, K.; Lusk, J.L. The Impact of Hormone Use Perception on Consumer Meat Preference. In Proceedings of the Southern Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Mobile, AL, USA, 4–7 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kehlbacher, A.; Bennett, R.; Balcombe, K. Measuring the consumer benefits of improving farm animal welfare to inform welfare labelling. Food Policy 2012, 37, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y. Urban Chinese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Pork with Certified Labels: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Silva, J.; Tirapicos Nunes, J.L. Inventory and characterisation of traditional Mediterranean pig production systems. Advantages and constraints towards its development. Acta Agric. Slov. 2013, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahelices, A.; Mesías, F.H.; Escribano, M.; Gaspar, P.; Elghannam, A. Are quality regulations displacing PDOs? A choice experiment study on Iberian meat products in Spain. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 16, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gong, X.; Qin, S.; Chen, X.; Zhu, D.; Hu, W.; Li, Q. Consumer preferences for pork attributes related to traceability, in-formation certification, and origin labeling: Based on China’s Jiangsu Province. Agribusiness 2017, 33, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Sonntag, W.I.; Glanz-Chanos, V.; Forum, S. Consumer interest in environmental impact, safety, health, and animal welfare aspects of modern pig production: Results of a cross-national choice experiment. Meat Sci. 2018, 137, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillman, D.; Smyth, J.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/997936/internet-phone-mail-and-mixedmode-surveys-the-tailored-design-method-pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Khachatryan, H.; Rihn, A.; Wei, X. Consumers’ Preferences for Eco-labels on Plants: The Influence of Trust and Consequentiality Perceptions. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021, 91, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariel, P.; Hoyos, D.; Meyerhoff, J.; Czajkowski, M.; Dekker, T.; Glenk, K.; Jacobsen, B.; Liebe, U.; Olsen, S.B.; Sagebiel, J.; et al. Environmental Valuation with Discrete Choice Experiments, Guidance on Design, Implementation and Data Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnichsen, O.; Olsen, S.B. Correcting for non-response bias in contingent valuation surveys concerning environmental non-market goods: An empirical investigation using an online panel. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Caso, G.; Cembalo, L.; Borrello, M. Is respondents’ inattention in online surveys a major issue for research? Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2020, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESOMAR. ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics; ESOMAR & GRBN: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019; (Licensed to Faculty of Economics in Osijek). [Google Scholar]

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Available online: https://dzs.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/657 (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Croatia in Figures, Zagreb, 2020. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/5locv4mx/croinfig_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Lin, W.; Ortega, D.L.; Caputo, V.; Lusk, J.L. Personality traits and consumer acceptance of controversial food technology: A cross-country investigation of genetically modified animal products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.; Lee, N.; Hötzel, M.; de Luna, M.; Sharma, A.; Idris, M.; Derkley, T.; Li, C.; Islam, M.; Iyasere, O.; et al. International perceptions of animals and the importance of their welfare. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 960379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić Milković, S.; Lončarić, R.; Crnčan, A.; Kristić, J.; Canavari, M. Consumer segments and preferences for PDO-labelled fresh pork: A choice experiment on the black Slavonian pig in Croatia. Meat Sci. 2025, 232, 110002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font i Furnols, M.; Skrlep, M.; Aluwé, M. Attitudes and beliefs of consumers towards pig welfare and pork quality. In Proceedings of the 60th International Meat Industry Conference MEATCON2019, Kopaonik, Serbia, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 1–8, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volume 333. [Google Scholar]

- 51; Akaichi, F.; Glenk, K.; Revoredo-Giha, C. Substitutes or Complements? Consumers’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Animal Welfare, Organic, Local and Low-Fat Food Attributes. In Proceedings of the 90th Annual Conference of the Agricultural Economics Society, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 4–6 April 2016; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoli, R.; Scarpa, R.; Napolitano, F.; Piasentier, E.; Naspetti, S.; Bruschi, V. Organic label as an identifier of environmentally related quality: A consumer choice experiment on beef in Italy. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012, 28, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velčovská, Š.; Del Chiappa, G. The food quality labels: Awareness and willingness to pay in the context of the Czech Republic. Acta Univ. Agric. et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2015, 63, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlino, V.M.; Borra, D.; Verduna, T.; Massaglia, S. Household Behavior with Respect to Meat Consumption: Differences between Households with and without Children. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font i Furnols, M.; Guerrero, L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabolek, I.; Miikuš, T.; Pavičić, Ž.; Matković, K.; Antunović, B.; Mesić, Ž. Regional differences in the attitudes of veterinary students in Croatia towards welfare of farm and companion animals. Vet. Stanica 2021, 52, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovato, S.; Pinto, A.; Di Martino, G.; Mascarello, G.; Rizzoli, V.; Marcolin, S.; Ravarotto, L. Purchasing Habits, Sustainability Perceptions, and Welfare Concerns of Italian Consumers Regarding Rabbit Meat. Foods 2022, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, S. How New Consumers’ Consumption Patterns Caused Changes in Food Distribution Channels in Croatia. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiru, C.; Thölke, H. Buying behaviour insights regarding animal welfare and environmental factors in North Western Germany. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Contemporary Marketing Issues (ICCMI), Thessaloniki, Greece, 21–23 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Narodne Novine. Pravilnik o Provedbi Izravne Potpore Poljoprivredi i IAKS Mjera Ruralnog Razvoja za 2022. Godinu [Regulation on the Implementation of Direct Payments in Agriculture and IAKS Rural Development Measures in 2022]. NN 27/2022. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2022_03_27_352.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Narodne Novine. Pravilnik o Provedbi Izravne Potpore Poljoprivredi i IAKS Mjera Ruralnog Razvoja za 2024. Godinu., 2023. [Regulation on the Implementation of Direct Payments in Agriculture and IAKS Rural Development Measures in 2022]. NN 157/2023. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2023_12_157_2415.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- HAPIH-Croatian Agency for Agriculture and Food. Pig Breeding, Annual Report for 2023, 2024. Available online: https://www.hapih.hr/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Svinjogojstvo-Godisnje-izvjesce-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Zakon o Poljoprivredi (”Narodne novine”, br. 118/18, 44/20, 127/20.—Odluka Ustavnog suda RH, 52/21 i 152/22). Pravilnik o Izmjenama i Dopunama Pravilnika o Provedbi Intervencija za Potporu Ulaganjima u Primarnu Poljoprivrednu Proizvodnju i Preradu Poljoprivrednih Proizvoda iz Strateškog Plana Zajedničke Poljoprivredne Politike Republike Hrvatske 2023–2027. [Regulation Amending the Regulation on the Implementation of Interventions to Support Investments in Primary Agricultural Production and Processing of Agricultural Products from the Strategic Plan of the Common Agricultural Policy of the Republic of Croatia 2023–2027]. NN 7/2024. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2024_01_7_134.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Dokazana Kvaliteta [Certified Quality], 2025. Available online: https://poljoprivreda.gov.hr/istaknute-teme/hrana-111/oznake-kvalitete/dokazana-kvaliteta/4226 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Croatian Agency for Agriculture and Food. Meat from Croatian Farms, 2025. Available online: https://hhfp.hapih.hr/meso/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

| M | Me | Mo | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshness and meat appearance (colour, marbling, drip loss) are important factors when I purchase fresh pork. | 4.28 | 4 | 4 | 0.840 |

| Breeding indigenous pig breeds (such as Black Slavonian pig) promotes sustainability and provides support to local farmers. | 4.26 | 4 | 5 | 0.846 |

| Local food production contributes to preserving traditional breeds and production methods. | 4.22 | 4 | 4 | 0.821 |

| Products should clearly indicate whether the meat comes from an indigenous breed (such as Black Slavonian pig) or from modern pig breeds. | 4.14 | 4 | 4 | 0.851 |

| Outdoor rearing of Black Slavonian pigs represents a more environmentally friendly production system. | 4.12 | 4 | 4 | 0.819 |

| I consider the taste of meat to be the most important factor. | 4.07 | 4 | 4 | 0.785 |

| Products should indicate whether pigs were reared according to higher welfare standards. | 4.03 | 4 | 4 | 0.863 |

| I consistently check the price when purchasing fresh boneless pork ham. | 4.02 | 4 | 4 | 1.031 |

| Locally produced food is healthier and more natural (produced using traditional methods). | 3.95 | 4 | 4 | 0.898 |

| Pigs should have the opportunity to express natural behaviours on the farm (rooting, wallowing in mud, etc.). | 3.94 | 4 | 4 | 0.838 |

| Meat from indigenous pig breeds (such as the Black Slavonian pig) has superior taste, juiciness, tenderness, and overall quality. | 3.90 | 4 | 4 | 0.849 |

| Higher animal welfare standards result in better meat quality. | 3.88 | 4 | 4 | 0.913 |

| Knowing the production location and methods for pork is important to me. | 3.87 | 4 | 4 | 0.851 |

| Product labels and information are very important as they indicate quality and food safety. | 3.87 | 4 | 4 | 0.884 |

| Indoor (intensive) pig farming leads to environmental problems (e.g., high water consumption, energy use, greenhouse gas emissions). | 3.74 | 4 | 4 | 0.897 |

| I prefer purchasing locally produced food even when it costs more. | 3.74 | 4 | 4 | 0.934 |

| I believe intensive (indoor) pig farming is cruel. | 3.63 | 4 | 4 | 0.985 |

| I link meat quality with the geographical origin of the breed. | 3.57 | 4 | 4 | 0.939 |

| Farm animal welfare is a concern of mine. | 3.57 | 4 | 3 | 0.954 |

| The rearing conditions of pigs are unimportant because they are unaware of better alternatives. | 3.51 | 4 | 3 | 1.079 |

| I am willing to pay a premium for pork produced under higher animal welfare standards. | 3.51 | 4 | 3 | 1.033 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm animal welfare is a concern of mine. | 0.842 | 0.079 | 0.163 | 0.089 |

| I believe intensive (indoor) pig farming is cruel. | 0.787 | 0.115 | 0.054 | 0.061 |

| Higher animal welfare standards result in better meat quality. | 0.742 | 0.166 | 0.181 | 0.180 |

| I am willing to pay a premium for pork produced under higher animal welfare standards. | 0.722 | 0.152 | 0.413 | −0.052 |

| Pigs should have the opportunity to express natural behaviours on the farm. | 0.700 | 0.235 | 0.134 | 0.115 |

| Products should indicate whether pigs were reared according to higher welfare standards. | 0.682 | 0.326 | 0.252 | 0.082 |

| Indoor (intensive) pig farming leads to environmental problems. | 0.501 | 0.478 | 0.181 | −0.029 |

| The rearing conditions of pigs are unimportant because they are unaware of better alternatives. | 0.450 | 0.171 | −0.371 | 0.120 |

| Breeding indigenous pig breeds (such as the Black Slavonian pig) promotes sustainability and provides support to local farmers. | 0.176 | 0.783 | 0.169 | 0.307 |

| Outdoor rearing of Black Slavonian pigs represents a more environmentally friendly production system. | 0.293 | 0.781 | 0.088 | 0.030 |

| Local food production contributes to preserving traditional breeds and production methods. | 0.181 | 0.721 | 0.221 | 0.402 |

| Products should clearly indicate whether the meat comes from an indigenous breed (such as the Black Slavonian pig) or from modern pig breeds. | 0.247 | 0.601 | 0.395 | 0.154 |

| Meat from indigenous pig breeds (such as Black Slavonian pig) has superior taste, juiciness, tenderness, and overall quality. | 0.134 | 0.598 | 0.487 | 0.168 |

| Locally produced food is healthier and more natural (produced using traditional methods). | 0.137 | 0.564 | 0.435 | 0.303 |

| I link meat quality with the geographical origin of the breed. | 0.163 | 0.277 | 0.746 | 0.030 |

| Knowing the production location and methods for pork is important to me. | 0.292 | 0.207 | 0.699 | 0.262 |

| Product labels and information are very important as they indicate quality and food safety. | 0.214 | 0.365 | 0.586 | 0.127 |

| I prefer purchasing locally produced food even when it costs more. | 0.324 | 0.432 | 0.551 | −0.152 |

| I consistently check the price when purchasing fresh boneless pork ham. | −0.010 | 0.123 | −0.179 | 0.782 |

| Freshness and meat appearance (colour, marbling, drip loss) are important factors when I purchase fresh pork. | 0.227 | 0.241 | 0.237 | 0.719 |

| I consider the taste of meat to be the most important factor. | 0.137 | 0.186 | 0.423 | 0.629 |

| % Variance Explained | 41.367 | 10.474 | 7.300 | 4.812 |

| Eigenvalues | 8.687 | 2.200 | 1.533 | 1.011 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.772 | 0.875 | 0.807 | 0.668 |

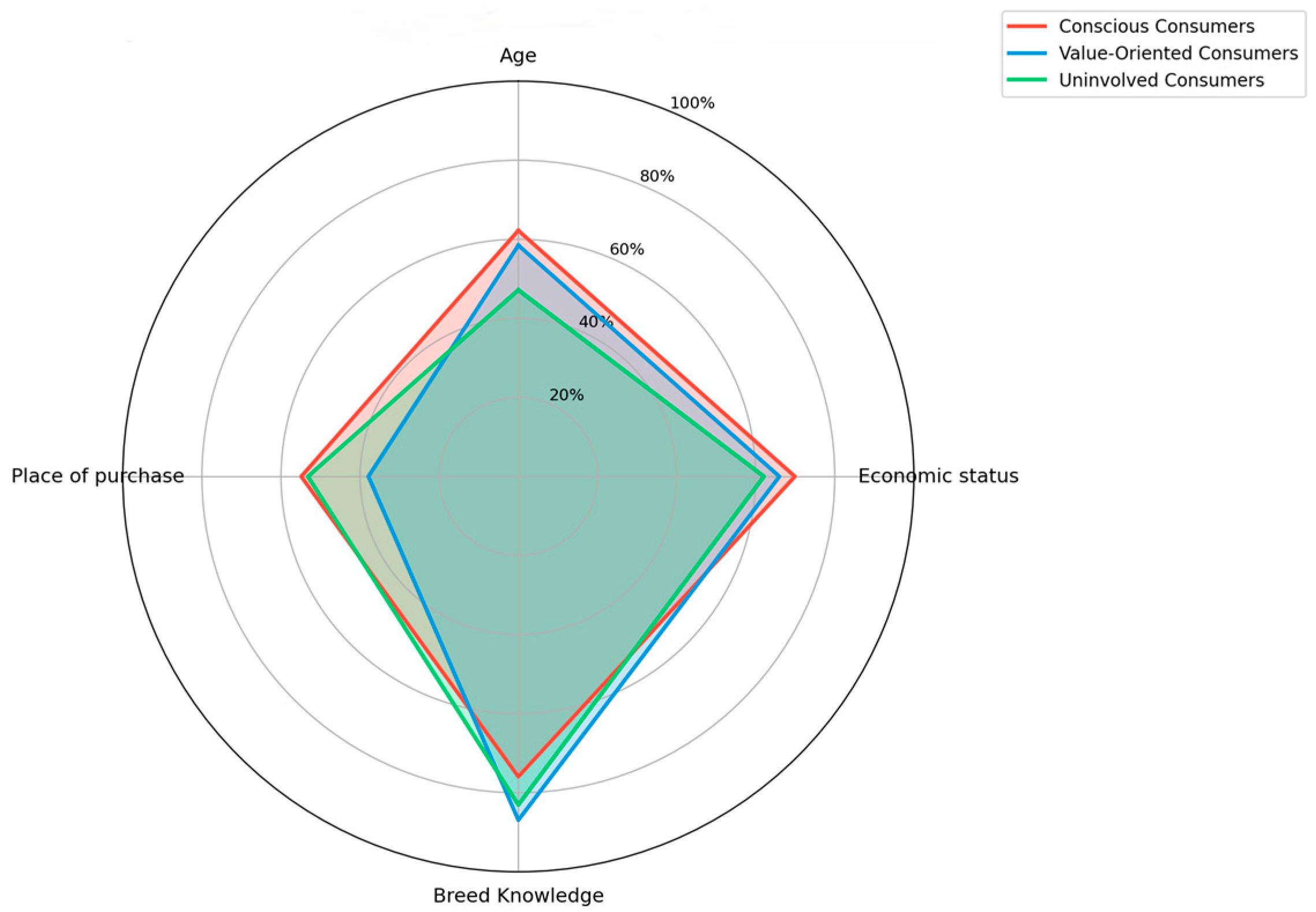

| Cluster 1 (n = 133) Conscious Consumers | Cluster 2 (n = 153) Value-Oriented Consumers | Cluster 3 (n = 124) Uninvolved Consumers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention to animal welfare | 0.63692 | −0.76926 | 0.26602 |

| Supporting local production and biodiversity | 0.71895 | 0.22839 | −1.05293 |

| Origin and information | −0.43028 | 0.44339 | −0.08557 |

| Price and intrinsic quality | 0.12743 | −0.11144 | 0.00082 |

| Model Fit Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Value | ||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 791.689 | ||

| Model χ2 (df = 60) | 103.211 *** | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.251 | ||

| McFadden R2 | 0.115 | ||

| Classification Accuracy (%) | 52.9 | ||

| Likelihood ratio tests | |||

| Predictor | χ2 | df | p |

| Gender | 1.028 | 2 | 0.598 |

| Age | 17.907 | 8 | 0.022 * |

| Residence | 0.212 | 2 | 0.899 |

| Region | 25.658 | 8 | 0.001 *** |

| Occupation | 3.568 | 8 | 0.894 |

| Education | 7.469 | 4 | 0.113 |

| Household size | 1.038 | 4 | 0.904 |

| Number of children in the household | 2.778 | 4 | 0.596 |

| Number of elders in the household | 0.949 | 4 | 0.917 |

| Family economic status | 19.932 | 6 | 0.003 ** |

| Purchase place | 15.949 | 4 | 0.003 ** |

| Paying price | 6.270 | 4 | 0.180 |

| Breed knowledge | 2.462 | 2 | 0.292 |

| B | SE | Wald | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscious Consumers vs. Uninvolved Meat Consumers | |||||

| Age (Reference: 55+) | |||||

| 18–24 years | −1.69 | 0.71 | 5.63 * | 0.18 | [0.05, 0.75] |

| 25–34 years | −1.24 | 0.48 | 6.60 ** | 0.29 | [0.11, 0.75] |

| 35–44 years | −0.86 | 0.52 | 2.75 | 0.42 | [0.15, 1.17] |

| 45–54 years | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 1.12 | [0.42, 3.02] |

| Region (Reference: Middle and South Adriatic) | |||||

| Central Croatia | −1.33 | 0.51 | 6.90 ** | 0.26 | [0.10, 0.71] |

| Central Croatia North-Western Croatia | −1.03 | 0.50 | 4.17 * | 0.36 | [0.13, 0.96] |

| Eastern Croatia | −0.40 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.67 | [0.23, 1.91] |

| Northern Adriatic and Lika | −1.18 | 0.54 | 4.74 * | 0.31 | [0.11, 0.89] |

| Economic Status (Reference: Above Average) | |||||

| Significantly Below Average | −2.28 | 0.87 | 6.88 ** | 0.10 | [0.02, 0.56] |

| Below Average | −1.25 | 0.50 | 6.30 * | 0.29 | [0.11, 0.76] |

| Average | −0.69 | 0.37 | 3.48 | 0.50 | [0.24, 1.04] |

| Value-Oriented Consumers vs. Uninvolved Meat Consumers | |||||

| Region (Reference: Middle and South Adriatic) | |||||

| Central Croatia | −1.92 | 0.52 | 13.68 *** | 0.15 | [0.05, 0.41] |

| Central Croatia North-Western Croatia | −1.35 | 0.51 | 7.17 ** | 0.26 | [0.10, 0.70] |

| Eastern Croatia | −0.32 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.73 | [0.26, 2.06] |

| Northern Adriatic and Lika | −1.03 | 0.53 | 3.75 | 0.36 | [0.13, 1.01] |

| Economic Status (Reference: Above Average) | |||||

| Significantly Below Average | −0.75 | 1.19 | 9.94 ** | 0.24 | [0.00, 0.24] |

| Below Average | −0.76 | 0.48 | 2.52 | 0.47 | [0.18, 1.20] |

| Average | −0.62 | 0.38 | 2.67 | 0.54 | [0.25, 1.13] |

| Purchase Place (Reference: Supermarket) | |||||

| Direct From Producer | −0.98 | 0.61 | 2.59 | 0.38 | [0.11, 1.24] |

| Butcher Shop | −0.93 | 0.30 | 9.42 ** | 0.39 | [0.22, 0.71] |

| Price Paid (Reference: ≥€10.04) | |||||

| €3.30–5.94 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 2.76 | 2.47 | [0.85, 7.20] |

| €6.08–9.90 | 1.26 | 0.54 | 5.34 * | 3.51 | [1.21, 10.19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jelić Milković, S.; Lončarić, R.; Kristić, J.; Crnčan, A.; Kralik, I.; Pečurlić, L.; Kranjac, D.; Canavari, M. Consumer Attitudes, Buying Behaviour, and Sustainability Concerns Toward Fresh Pork: Insights from the Black Slavonian Pig. Sustainability 2026, 18, 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020980

Jelić Milković S, Lončarić R, Kristić J, Crnčan A, Kralik I, Pečurlić L, Kranjac D, Canavari M. Consumer Attitudes, Buying Behaviour, and Sustainability Concerns Toward Fresh Pork: Insights from the Black Slavonian Pig. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020980

Chicago/Turabian StyleJelić Milković, Sanja, Ružica Lončarić, Jelena Kristić, Ana Crnčan, Igor Kralik, Lucija Pečurlić, David Kranjac, and Maurizio Canavari. 2026. "Consumer Attitudes, Buying Behaviour, and Sustainability Concerns Toward Fresh Pork: Insights from the Black Slavonian Pig" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020980

APA StyleJelić Milković, S., Lončarić, R., Kristić, J., Crnčan, A., Kralik, I., Pečurlić, L., Kranjac, D., & Canavari, M. (2026). Consumer Attitudes, Buying Behaviour, and Sustainability Concerns Toward Fresh Pork: Insights from the Black Slavonian Pig. Sustainability, 18(2), 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020980