Elevating Morals, Elevating Actions: The Interplay of CSR, Transparency, and Guest Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Hotels

Abstract

1. Introduction

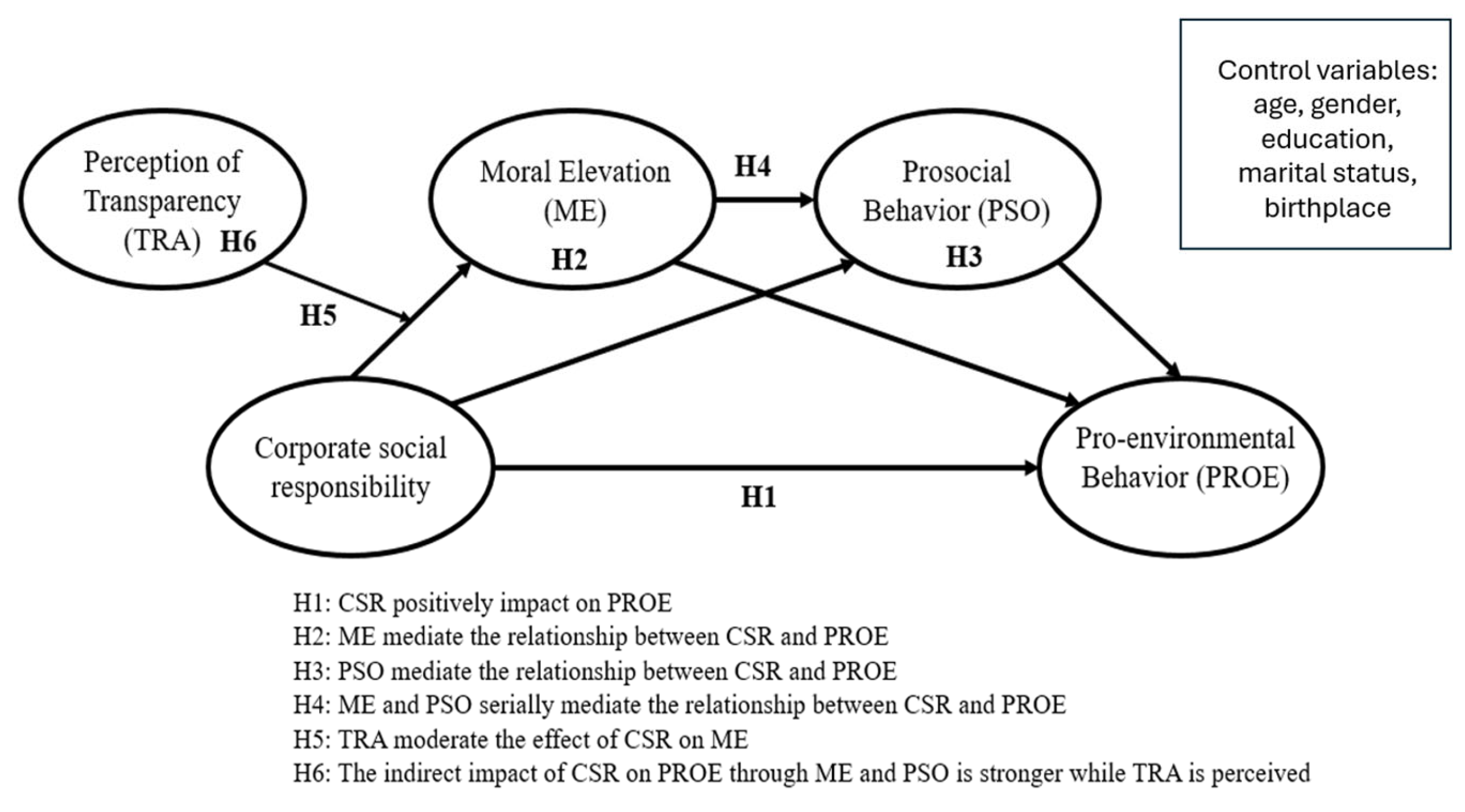

2. Theoretical Framework, Hypotheses, and Research Model

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.2. The Mediating Role of Moral Elevation

2.3. The Mediating Role of Pro-Social Behavior

2.4. Moral Elevation and Pro-Social Behavior as the Serial Mediators

2.5. The Moderating Role of Perception of Transparency

3. Method

3.1. Analysis Strategy

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis and Common Method Bias Check

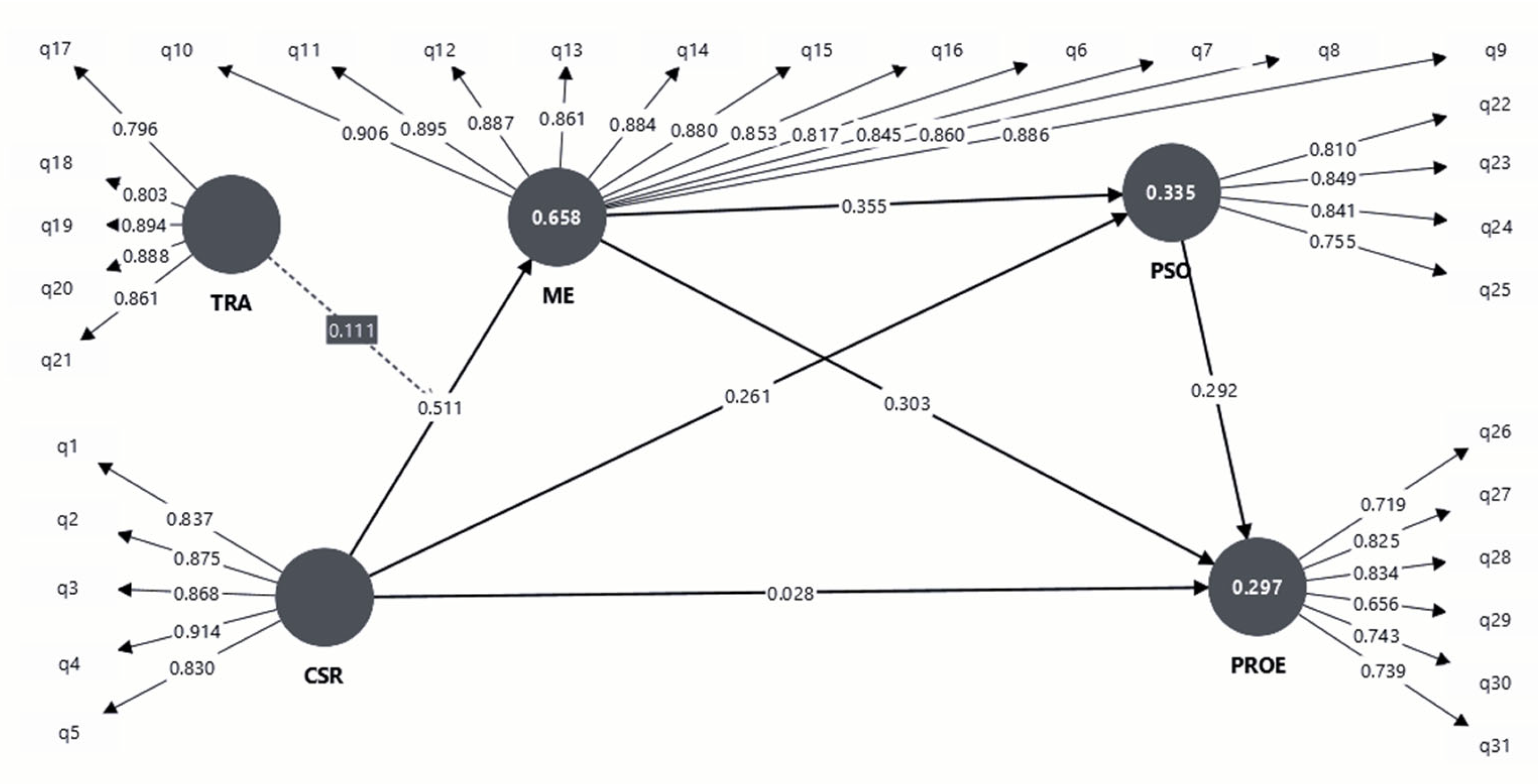

4.2. Measurement Model Quality

4.3. Discriminant Validity

4.4. Structural Model Assessment

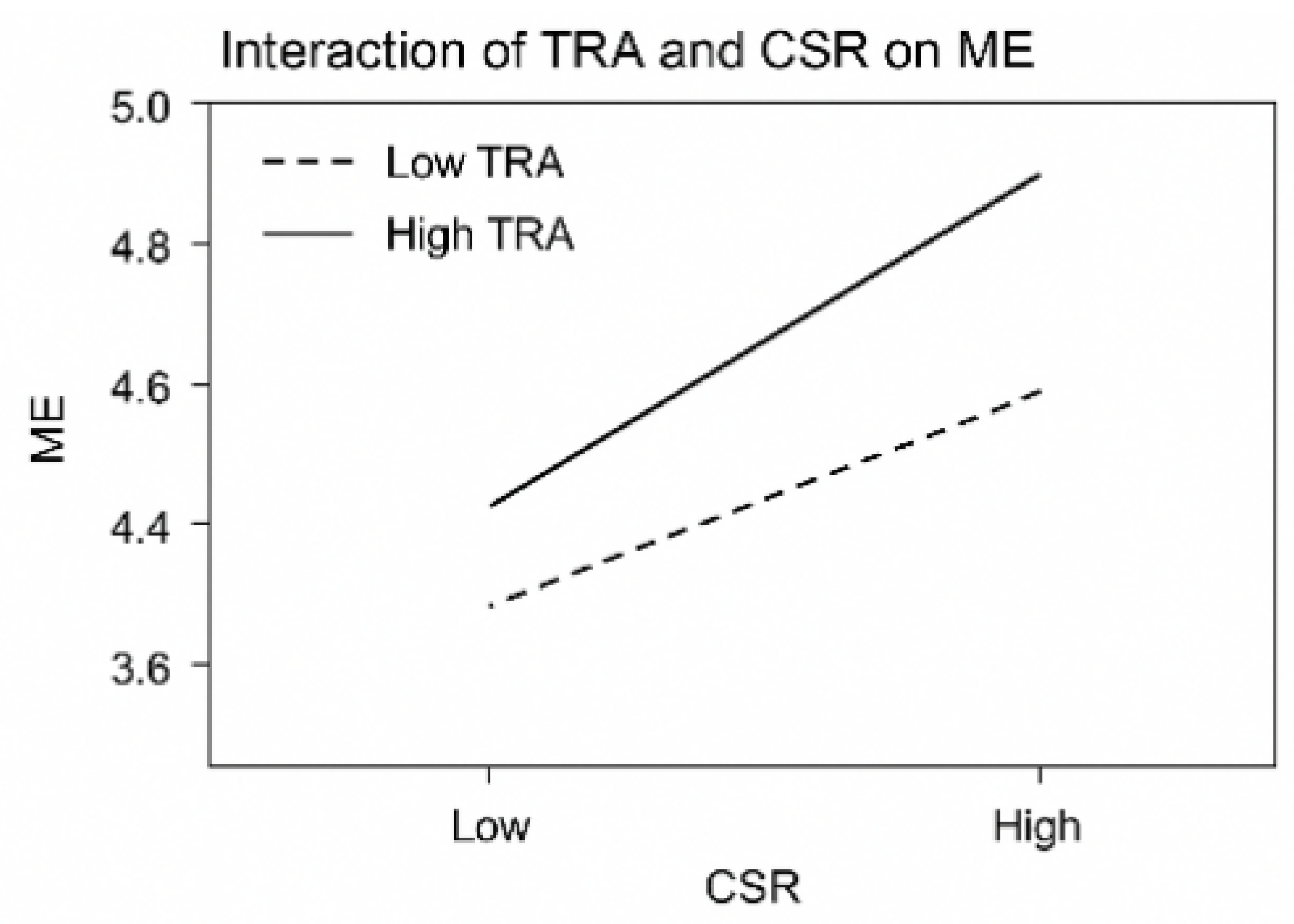

4.5. Direct and Interaction Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. General Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| PSO | Pro-social Behavior |

| PROE | Pro-environmental Behavior |

| ME | Moral Elevation |

| TRA | Perception of Transparency |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| OCB | Organizational Citizenship Behavior |

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Alnawas, I.; El Hedhli, K.; Abu Farah, A.; Zourrig, H. The effects of hotels’ environmental sustainability communication strategies on social media engagement and brand advocacy: The roles of communication characteristics and customers’ personality traits. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 31, 596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Raza, A.; Mansoor, A.; Khan, M.S.; Lee, J.W.C. Trends and patterns in pro-environmental behaviour research: A bibliometric review and research agenda. Benchmarking 2023, 30, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Arasli, H. Workplace spirituality and organization sustainability: A theoretical perspective on hospitality employees’ sustainable behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1583–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. The link among board characteristics, CSR performance, and financial performance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutshi, A.; Creed, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Croy, G.; Dahms, S. Sustainability during the COVID pandemic: Analysis of hotel association communication. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3840–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S. Social and sustainable: Exploring social media use for promoting sustainable behaviour among Indian tourists. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021, 36, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Taheri, B.; Okumus, F.; Gannon, M. Understanding the importance that consumers attach to social media sharing (ISMS): Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de los Salmones, M.d.M.; Herrero, A.; Martinez, P. CSR communication on Facebook: Attitude towards the company and intention to share. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1391–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Nazarian, A.; Foroudi, P.; Seyyed Amiri, N.; Ezatabadipoor, E. How CSR contributes to strengthening brand loyalty, hotel positioning and intention to revisit. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1897–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; García de los Salmones, M.d.M.; Liu, M.T. Maximising business returns to corporate social responsibility communication: An empirical test. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.K.C.; Mark, C.K.M.; Yeung, M.P.S.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Graham, C.A. The role of the hotel industry in the response to emerging epidemics: A case study of SARS in 2003 and H1N1 swine flu in 2009 in Hong Kong. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, K.F.; Pérez, A.; Sahibzada, U.F. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hericher, C.; Bridoux, F.; Raineri, N. I feel morally elevated by my organization’s CSR, so I contribute to it. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 169, 114282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, B.B.; Jackson, C.L.; Boss, A.D.; Tay, L.; Boss, R.W. Be fair, your employees are watching: A relational response model of external third-party justice. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 68, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.A.; Cryder, C. Prosocial consumer behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, S.; McIntosh, A.; Cockburn-Wootten, C. Advancing a social justice-orientated agenda through research: A review of refugee-related research in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 32, 1142–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Cai, G.; Han, H. Festival travellers’ pro-social and protective behaviours against COVID-19 in the time of pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3256–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Fang, S. Mechanisms of self-control in the influence of moral elevation on pro-social behavior: A study based on an experimental paradigm. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Shao, Y.; Sun, B.; Xie, R.; Li, W.; Wang, X. How can prosocial behavior be motivated? The different roles of moral judgment, moral elevation, and moral identity among young Chinese. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S. How companies’ good deeds encourage consumers to adopt pro-social behavior. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Basil, D.Z.; Wymer, W. Using social marketing to enhance hotel reuse programs. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R.M.; Smith, A.J. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. SSRN Electron. J. 2002, 32, 237–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, A.K.; Tomlinson, E.C. Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organization–stakeholder relationships. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1784–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, B. Give the emperor a mirror: Toward developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. J. Public Relat. Res. 2008, 21, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y.; Jha, S. Green hotel adoption: A personal choice or social pressure? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3287–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhshik, A.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Ozturen, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Memorable tourism experiences and critical outcomes among nature-based visitors: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 2981–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Hassannia, R.; Kim, T.T.; Enea, C. Tourism destination social responsibility and the moderating role of self-congruity. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Akhshik, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Application of machine learning to predict visitors’ green behavior in marine protected areas: Evidence from Cyprus. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2479–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.V.; Nguyen, D.M.; Nguyen, T. Fostering green customer citizenship behavioral intentions through green hotel practices: The roles of pride, moral elevation, and hotel star ratings. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 33, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Priporas, C.-V.; McPherson, M.; Manyiwa, S. CSR-related consumer scepticism: A review of the literature and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 169, 114294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.J. Effectiveness of corporate social marketing on prosocial behavior and hotel loyalty in a time of pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 117, 103635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M. Corporate social marketing in tourism: To sleep or not to sleep with the enemy? J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Albishri, N.A. Driving employee organizational citizenship behaviour through CSR: An empirical study in the context of luxury hotels. Acta Psychol. 2024, 245, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V.; Cialdini, R.B. Invoking social norms: A social psychology perspective on improving hotels’ linen-reuse programs. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.J.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-C. Government and social trust vs. hotel response efficacy: A protection motivation perspective on hotel stay intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, H. Effect of CSR contribution timing during the COVID-19 pandemic on consumers’ prepayment purchase intentions: Evidence from the hospitality industry in China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D. Environmental strategies and their impact on hotel performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Reyes, L.; Chen, C.-K. The evolution and convergence of total quality management and management theories. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 1108–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grosbois, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting in the cruise tourism industry: A performance evaluation using a new institutional theory–based model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Biagio, S. The perception of socially and environmentally responsible practices based on values and cultural environment from a customer perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, S.; Huh, C. Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J.; Onrust, M.; Verhoef, P.C.; Bügel, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer attitudes and retention—The moderating role of brand success indicators. Mark. Lett. 2017, 28, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good…and does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2007, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Beyond good intentions: Designing CSR initiatives for greater social impact. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.B.; Khandelwal, C.; Sarkar, P.; Dangayach, G.S.; Meena, M.L. Recent research progress on corporate social responsibility of hotels. Eng. Proc. 2023, 37, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algoe, S.B.; Haidt, J. Witnessing excellence in action: The “other-praising” emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The positive emotion of elevation. Prev. Treat. 2000, 3, 33c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. Wired to be inspired. In The Compassionate Instinct; Keltner, D., Marsh, J., Smith, J.A., Eds.; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K.S. Elevation predicts domain-specific volunteerism 3 months later. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.L.; Nakamura, J.; Siegel, J.T.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Elevation and mentoring: An experimental assessment of causal relations. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vyver, J.; Abrams, D. Testing the prosocial effectiveness of the prototypical moral emotions: Elevation increases benevolent behaviors and outrage increases justice behaviors. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Qing, T.; Fan, X.; Hui, S.C. Perceived corporate social responsibility and employee voluntary pro-environmental behavior: Does moral motive matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Impact of CSR on customer citizenship behavior: Mediating the role of customer engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Li, Y. How to fuel employees’ prosocial behavior in the hotel service encounter. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, D.; Tuan, A.; Dalli, D.; Viglia, G.; Okumus, F. Do consumers care about CSR in their online reviews? An empirical analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 85, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonschmidt, H.; Lund-Durlacher, D. Stimulating food waste reduction behaviour among hotel guests through context manipulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Youth travelers and waste reduction behaviors while traveling to tourist destinations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S.T.; Maria, J. Forty years of the theory of planned behavior: A bibliometric analysis (1985–2024). Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Pong, P.; Wang, L. The efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour and value-belief-norm theory for predicting young Chinese intention to choose green hotels. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthé, E.; Morrongiello, C.; Bonnefoy-Claudet, L.; Bezançon, M.; Bilgihan, A. Do hotels’ green efforts lead guests to adopt sustainable behaviors? Mediating roles of perceived motives, gratitude, and green trust. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 131, 104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boğan, E.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Çalışkan, C.; Cheema, S. Employee negative reactions to CSR: Corporate hypocrisy and symbolic CSR attributions as serial mediators. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 120, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, N.; Brockman, P. The local roots of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 142, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Lee, M.J.; Chua, B.-L.; Han, H. An integrated framework of behavioral reasoning theory, theory of planned behavior, moral norm and emotions for fostering hospitality and tourism employees’ sustainable behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4317–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; McFerran, B.; Laven, M. Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.L.; Siegel, J.T. A moral act, elevation, and prosocial behavior: Moderators of morality. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Zelli, A.; Capanna, C. A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wei, W. Consumers’ pro-environmental behavior and the underlying motivations: A comparison between household and hotel settings. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Peng, X. Can the home experience in luxury hotels promote pro-environmental behavior among guests? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyahia, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Elshaer, I.A.; Mohammad, A.A.A. Greenwashing behavior in hotels industry: The role of green transparency and green authenticity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustvedt, G.; Kang, J. Consumer perceptions of transparency: A scale development and validation. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2013, 41, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Schuberth, F. Using confirmatory composite analysis to assess emergent variables in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G.C.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska-Menkes, M.; Aluchna, M.; Kamiński, B. True transparency or mere decoupling? The study of selective disclosure in sustainability reporting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2024, 98, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhai, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J. CSR communication in hospitality: Fostering hotel guests’ climate (change) engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Manchón, L.; Fernández-Cavia, J.; Estanyol, E.; Van-Bergen, P. Differences across generations in the perception of the ethical, social, environmental, and labor responsibilities of the most reputed Spanish organizations. Prof. Inf. 2024, 33, 0302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, J.; Marcinkowska, E. Environmental CSR and the purchase declarations of Generation Z consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berényi, L.; Deutsch, N. Gender differences in attitudes to corporate social responsibility among Hungarian business students. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2017, 14, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.L.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Smit, C.; de Vries, H.; Pieterse, M.E. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, K.S.; Takahashi, Y.; Soe, A.T.; Lwin, C.M. Hotel employees’ pro-environmental behavior: A functionalist approach to positive moral psychology. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 14729–14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Mahmood, A.; Han, H. Unleashing the potential role of CSR and altruistic values to foster pro-environmental behavior by hotel employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, J. Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Int. J. Mark. Strateg. 2024, 6, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Song, B.; Ferguson, M.A.; Kochhar, S. Employees’ prosocial behavioral intentions through empowerment in CSR decision-making. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Che, C.; Jeong, C. Hotel guests’ psychological distance of climate change and environment-friendly behavior intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampora, A.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Merli, R.; Ali, F. The theoretical development and research methodology in green hotels research: A systematic literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 187 | 43.9 |

| Female | 239 | 56.1 | |

| Marital Status | Single/Divorced | 263 | 61.7 |

| Married | 163 | 38.3 | |

| Birthplace | Urban | 340 | 79.8 |

| Rural | 86 | 20.2 | |

| Education Level | Primary School | 10 | 2.3 |

| Secondary/High School | 88 | 20.7 | |

| 2-Year College | 83 | 19.5 | |

| 4-Year College Degree | 173 | 40.6 | |

| Master’s Degree or Above | 72 | 16.9 | |

| Age Group | 18–27 | 167 | 39.2 |

| 28–37 | 117 | 27.5 | |

| 38–47 | 69 | 16.2 | |

| 48–57 | 41 | 9.6 | |

| 58 and Over | 32 | 7.5 |

| Variable | Skewness | Kurtosis | Outer Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate social Responsibility (CSR) | 0.915 | 0.937 | 0.749 | |||

| CSR1 | −0.505 | −0.590 | 0.837 | |||

| CSR2 | −0.369 | −0.707 | 0.875 | |||

| CSR3 | −0.636 | −0.318 | 0.868 | |||

| CSR4 | −0.487 | −0.549 | 0.914 | |||

| CSR5 | −0.690 | −0.514 | 0.830 | |||

| Moral Elevation (ME) | 0.968 | 0.972 | 0.758 | |||

| ME1 | −0.419 | −0.738 | 0.817 | |||

| ME2 | −0.492 | −0.538 | 0.845 | |||

| ME3 | −0.440 | −0.700 | 0.860 | |||

| ME4 | −0.339 | −0.926 | 0.886 | |||

| ME5 | −0.330 | −0.866 | 0.906 | |||

| ME6 | −0.308 | −0.872 | 0.895 | |||

| ME7 | −0.449 | −0.762 | 0.887 | |||

| ME8 | −0.326 | −0.501 | 0.861 | |||

| ME9 | −0.343 | −0.807 | 0.884 | |||

| ME10 | −0.503 | −0.678 | 0.880 | |||

| ME11 | −0.489 | −0.676 | 0.853 | |||

| Pro-Environmental Behavior (PROE) | 0.848 | 0.888 | 0.571 | |||

| PROE1 | −1.318 | 0.667 | 0.719 | |||

| PROE2 | −0.774 | −0.203 | 0.825 | |||

| PROE3 | −0.788 | −0.103 | 0.834 | |||

| PROE4 | −0.527 | −0.869 | 0.656 | |||

| PROE5 | −0.623 | −0.647 | 0.743 | |||

| PROE6 | −0.786 | −0.226 | 0.739 | |||

| Pro-social Behavior (PSO) | 0.835 | 0.887 | 0.664 | |||

| PSO1 | −0.693 | −0.176 | 0.810 | |||

| PSO2 | −0.592 | −0.406 | 0.849 | |||

| PSO3 | −0.771 | −0.080 | 0.841 | |||

| PSO4 | −0.750 | −0.194 | 0.755 | |||

| Perception of Transparency (TRA) | 0.904 | 0.928 | 0.721 | |||

| TRA1 | −0.842 | 0.019 | 0.796 | |||

| TRA2 | −0.707 | −0.299 | 0.803 | |||

| TRA3 | −0.606 | −0.362 | 0.894 | |||

| TRA4 | −0.623 | −0.557 | 0.888 | |||

| TRA5 | −0.658 | −0.475 | 0.861 |

| Construct | CSR | ME | PROE | PSO | TRA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 0.865 | ||||

| ME | 0.757 | 0.871 | |||

| PROE | 0.411 | 0.485 | 0.755 | ||

| PSO | 0.528 | 0.548 | 0.474 | 0.815 | |

| TRA | 0.699 | 0.718 | 0.477 | 0.500 | 0.850 |

| Variables | VIF |

|---|---|

| CSR →ME | 1.966 |

| CSR → PROE | 2.448 |

| CSR → PSO | 2.344 |

| ME → PROE | 2.533 |

| ME → PSO | 2.344 |

| PSO → PROE | 1.504 |

| TRA → ME | 2.107 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 1.205 |

| Path | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → ME | 0.514 | 0.516 | 0.047 | 11.022 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PROE | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.066 | 0.686 | 0.493 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.264 | 0.266 | 0.070 | 3.801 | 0.000 |

| ME → PSO | 0.348 | 0.347 | 0.071 | 4.906 | 0.000 |

| PSO → PROE | 0.307 | 0.310 | 0.058 | 5.259 | 0.000 |

| TRA → ME | 0.411 | 0.409 | 0.053 | 7.692 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PROE | 0.292 | 0.292 | 0.074 | 3.916 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PSO | 0.143 | 0.142 | 0.035 | 4.104 | 0.000 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.034 | 3.298 | 0.001 |

| TRA × CSR → PSO | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 2.655 | 0.008 |

| TRA × CSR → PROE | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 2.277 | 0.023 |

| Total Indirect effects | |||||

| CSR → ME → PSO | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.040 | 4.453 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PSO → PROE | 0.081 | 0.082 | 0.024 | 3.336 | 0.001 |

| CSR → ME → PSO → PROE | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.017 | 3.166 | 0.002 |

| ME → PSO → PROE | 0.107 | 0.108 | 0.032 | 3.377 | 0.001 |

| TRA → ME → PSO | 0.143 | 0.142 | 0.035 | 4.104 | 0.000 |

| TRA → ME → PSO → PROE | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.014 | 3.144 | 0.002 |

| TRA × CSR → ME → PSO | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 2.655 | 0.008 |

| TRA × CSR → ME → PSO → PROE | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 2.277 | 0.023 |

| Total Direct Effect | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → ME | 0.511 | 0.512 | 0.046 | 10.992 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PROE | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.079 | 0.352 | 0.725 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.261 | 0.263 | 0.068 | 3.846 | 0.000 |

| ME → PROE | 0.303 | 0.307 | 0.080 | 3.770 | 0.000 |

| ME → PSO | 0.355 | 0.356 | 0.067 | 5.303 | 0.000 |

| PSO → PROE | 0.292 | 0.294 | 0.057 | 5.086 | 0.000 |

| TRA → ME | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.053 | 7.844 | 0.000 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.034 | 3.306 | 0.001 |

| Total indirect effect | |||||

| CSR → PROE | 0.284 | 0.287 | 0.043 | 6.658 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.181 | 0.182 | 0.038 | 4.731 | 0.000 |

| ME → PROE | 0.104 | 0.104 | 0.028 | 3.671 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PROE | 0.169 | 0.171 | 0.042 | 3.975 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PSO | 0.148 | 0.147 | 0.034 | 4.371 | 0.000 |

| TRA × CSR → PROE | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.016 | 2.887 | 0.004 |

| TRA × CSR → PSO | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.015 | 2.720 | 0.007 |

| Total effect | |||||

| CSR → ME | 0.511 | 0.512 | 0.046 | 10.992 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PROE | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.055 | 5.617 | 0.000 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.443 | 0.445 | 0.044 | 10.132 | 0.000 |

| ME → PROE | 0.407 | 0.411 | 0.079 | 5.176 | 0.000 |

| ME → PSO | 0.355 | 0.356 | 0.067 | 5.303 | 0.000 |

| PSO → PROE | 0.292 | 0.294 | 0.057 | 5.086 | 0.000 |

| TRA → ME | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.053 | 7.844 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PROE | 0.169 | 0.171 | 0.042 | 3.975 | 0.000 |

| TRA → PSO | 0.148 | 0.147 | 0.034 | 4.371 | 0.000 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.034 | 3.306 | 0.001 |

| TRA × CSR → PROE | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.016 | 2.887 | 0.004 |

| TRA × CSR → PSO | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.015 | 2.720 | 0.007 |

| Path Coefficient | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | LLCI 2.5% | ULCI 97.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → ME | 0.511 | 0.512 | 0.419 | 0.602 |

| CSR → PROE | 0.028 | 0.025 | −0.129 | 0.177 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.261 | 0.263 | 0.132 | 0.395 |

| ME → PROE | 0.303 | 0.307 | 0.146 | 0.466 |

| ME → PSO | 0.355 | 0.356 | 0.218 | 0.484 |

| PSO → PROE | 0.292 | 0.294 | 0.178 | 0.402 |

| TRA → ME | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.308 | 0.516 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.043 | 0.175 |

| Total indirect effect | ||||

| CSR → PROE | 0.284 | 0.287 | 0.207 | 0.375 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.181 | 0.182 | 0.109 | 0.259 |

| ME → PROE | 0.104 | 0.104 | 0.054 | 0.164 |

| TRA → PROE | 0.169 | 0.171 | 0.092 | 0.260 |

| TRA → PSO | 0.148 | 0.147 | 0.082 | 0.217 |

| TRA × CSR → PROE | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.017 | 0.078 |

| TRA × CSR → PSO | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.069 |

| Total effect | ||||

| CSR → ME | 0.511 | 0.512 | 0.419 | 0.602 |

| CSR → PROE | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.202 | 0.418 |

| CSR → PSO | 0.443 | 0.445 | 0.357 | 0.528 |

| ME → PROE | 0.407 | 0.411 | 0.252 | 0.563 |

| ME → PSO | 0.355 | 0.356 | 0.218 | 0.484 |

| PSO → PROE | 0.292 | 0.294 | 0.178 | 0.402 |

| TRA → ME | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.308 | 0.516 |

| TRA → PROE | 0.169 | 0.171 | 0.092 | 0.260 |

| TRA → PSO | 0.148 | 0.147 | 0.082 | 0.217 |

| TRA × CSR → ME | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.043 | 0.175 |

| TRA × CSR → PROE | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.017 | 0.078 |

| TRA × CSR → PSO | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.069 |

| Hypothesis | Predicted Relationship | Relevant Path(s) in the Table | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CSR → PROE | CSR → PROE | Not supported | β = 0.045, t = 0.686, p = 0.493 |

| H2: ME mediates CSR → PROE | CSR → ME → PROE | Supported | Indirect β = 0.157, 95% CI [0.075, 0.246]; CSR → ME is significant (β = 0.514, p < 0.001) |

| H3: PSO mediates CSR → PROE | CSR → PSO → PROE | Supported | Indirect β = 0.081, t = 3.336, p = 0.001 |

| H4: ME & PSO serially mediate CSR → PROE | CSR → ME → PSO → PROE | Supported | Indirect β = 0.055, t = 3.166, p = 0.002 |

| H5: TRA moderates CSR → ME | TRA × CSR → ME | Supported | β = 0.111, t = 3.298, p = 0.001 |

| H6: The serial indirect CSR → ME → PSO → PROE is stronger when TRA is high (moderated serial mediation) | TRA × CSR → ME → PSO → PROE | Supported | Indirect β = 0.012, t = 2.277, p = 0.023 (CI does not include zero) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yildirim, K.A.; Kilic, H.; Rezapouraghdam, H. Elevating Morals, Elevating Actions: The Interplay of CSR, Transparency, and Guest Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Hotels. Sustainability 2026, 18, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020866

Yildirim KA, Kilic H, Rezapouraghdam H. Elevating Morals, Elevating Actions: The Interplay of CSR, Transparency, and Guest Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Hotels. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020866

Chicago/Turabian StyleYildirim, Kutay Arda, Hasan Kilic, and Hamed Rezapouraghdam. 2026. "Elevating Morals, Elevating Actions: The Interplay of CSR, Transparency, and Guest Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Hotels" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020866

APA StyleYildirim, K. A., Kilic, H., & Rezapouraghdam, H. (2026). Elevating Morals, Elevating Actions: The Interplay of CSR, Transparency, and Guest Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Hotels. Sustainability, 18(2), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020866

_Li.png)