1. Introduction

Evaluating Tourist Experience (TX) turns a diffuse journey into actionable evidence for design and management. Coupled with sustainability goals, TX metrics link visitor appraisals to environmental, socio-cultural, and economic performance, guiding high-impact interventions and consistent benchmarking across destinations.

TX is approached here through a Customer Experience (CX) lens that treats the journey as a before–during–after process in which tangible service attributes are braided with emotions, perceptions, and culturally shaped expectations [

1,

2]. From this perspective, tourism takes place within a socio-cultural and economic framework that motivates journey-based evaluation and emphasizes the design of encounters across multiple touchpoints [

1]. TX is inherently multidimensional: affective responses, cultural embeddedness, perceived authenticity, recreational stimulation, and the enabling environment interact in ways that complicate measurement and comparison across destinations. This complexity has led to a variety of TX frameworks in the literature, with some emphasizing memorable episodes [

3], others foregrounding service systems or place identity [

4]. However, no single reference model has achieved consensus. Consequently, there is a practical need for parsimonious, theory-aligned structures that retain conceptual coverage while supporting reliable diagnosis and benchmarking.

In prior work, we developed a broader post-pandemic TX scale for Valparaíso, Chile, that combined experiential antecedents with a global appraisal and downstream loyalty [

5]. The present study refines that instrument by focusing on five stable, managerially actionable facets—Emotions (EMS), Local Culture (CTL), Authenticity (AUT), Entertainment (ENT), and Servicescape (SVS). The goal is a compact model with clearer comparability across contexts and time, without sacrificing theoretical grounding or diagnostic value.

Guided by these motivations, we pursue two objectives: (i) to confirm a theoretically grounded TX measurement structure and (ii) to test a mediational mechanism in which the five antecedents shape a holistic appraisal—Global Perception (GEN)—that, in turn, governs Destination Loyalty (LOY). We deliberately chose to keep the model compact. We aimed to offer a structure that practitioners could realistically adopt, rather than a highly elaborate framework that would be difficult to use outside academic settings.

We hypothesize positive paths from EMS, CTL, AUT, ENT, and SVS to GEN (H1–H5), and from GEN to LOY (H6). To assess this structure with ordered-category indicators typical of experience research, we estimate an ordinal SEM (DWLS/WLSMV). We emphasize that H1–H6 are explicitly theory-derived from the TX/CX and experience-economy studies summarized below [

2,

3,

4].

From a Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) perspective, TX can be seen as a design challenge in hybrid (digital-physical) systems. Elements such as interface cues, information architecture, accessibility, and affective affordances shape cognitive load, trust, and perceived usability across various touchpoints. This, in turn, impacts GEN and future customer loyalty [

2,

6]. This view closely aligns with the principles of sustainable tourism. The sustainability pillars of UN Tourism—environmental integrity, socio-cultural vitality, and viable economics—match our strategic levers. For example, SVS encourages resource-efficient, safe, and accessible operations; CTL and AUT focus on heritage stewardship and maintaining respectful host-guest relationships; ENT supports low-impact, locally rooted programming; and EMS promotes pro-social and pro-environmental engagement. As a result, progress in GEN reflects not only better experiences but also design principles that support long-term destination sustainability [

7].

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. User Experience

Within HCI, User Experience (UX) has evolved from a software-centric notion into a comprehensive construct that encompasses the totality of a person’s perceptions, emotions, cognitions, and behavioral responses across an encounter with artifacts and services. While SIGCHI delineates HCI’s remit around the design, implementation, use, and evaluation of interactive computing systems [

8], international standards explicitly broaden UX to the perceptual and affective responses arising from both the actual and the anticipated use of any product, system, or service, thereby decoupling UX from software alone and situating it in broader socio-technical contexts [

9]. We find this decoupling particularly useful for tourism, where visitors constantly move between digital, physical, and social interfaces that cannot be understood in isolation. This perspective foregrounds the temporality of experience—pre-use expectations and mental models, in-use appraisal under task and environmental constraints, and post-use reflection and memory consolidation—alongside the interplay of pragmatic qualities and hedonic qualities (stimulation, identification, meaning) that jointly determine judgments of value and satisfaction.

In tourism, travelers engage in hybrid journeys that weave digital touchpoints with on-site, embodied interactions mediated by infrastructures, servicescapes, and social co-presence; consequently, UX must capture emotions such as curiosity, delight, anxiety, and awe; cognitive processes like sense-making and trust calibration; and conative outcomes including intention to continue, recommend, or return. Empirically, domain-grounded UX evaluations have demonstrated the utility of inspection-based and empirical methodologies tailored to tourism-related media and settings—for example, studies of online travel agencies that examine information scent, credibility cues, and transaction clarity [

10,

11,

12], investigations of virtual museums that assess narrative coherence, spatial orientation, and cultural interpretation quality [

13,

14,

15], and assessments of national parks that consider signage legibility, accessibility, and wayfinding under varying environmental conditions [

16]. In our view, what many of these contributions still underplay is how such design details accumulate into a single, memorable appraisal—a gap that TX-focused SEM can help address.

Building on these strands, specialized heuristic sets and evaluation procedures designed for sustainable touristic contexts have been proposed to bridge generic UX criteria with phenomena distinctive to TX, enabling more sensitive diagnostics and actionable redesign guidance.

2.2. Service Science & Customer Experience

Service science provides the conceptual foundation for understanding how organizations create value with and for customers through interdependent constellations of people, technologies, processes, and information. In Maglio and Spohrer’s influential formulation, it is “the study of service systems, which are dynamic value co-creation configurations of resources (people, technology, organizations, and shared information)” [

17]. This perspective is fundamentally interdisciplinary, integrating organizational studies, human factors, information systems, and business to explain how service systems interact, adapt, and evolve as they co-create value across time and contexts [

18]. Within this frame, experiential marketing reframes the managerial focus from features and transactions to orchestrated experiences: Schmitt argues for “products, communications, and marketing campaigns that awaken senses and reach the heart of the consumer” and articulates strategic experiential modules spanning sensory, affective, cognitive, bodily/behavioral, lifestyle, and social-identity domains [

19]. In urban tourism, we frequently observe these modules overlapping in practice—for instance, when a single viewpoint simultaneously engages the senses, prompts reflection, and signals a distinctive local identity.

Building on these premises, CX has become central to service science, yet remains a contested concept. Laming and Mason emphasize the physical and emotional arc from first conscious contact through post-consumption [

2], Joshi portrays CX as the cumulative set of experiences arising within a service relationship [

20], and LaSalle and Britton similarly foreground the chain of interactions between customers and organizational offerings that provoke evaluative reactions [

21]. Operationally, the CX construct is materialized at “touchpoints,” the moments when customers encounter any product, service, or system across channels, which collectively shape experience quality [

22]. Empirical work further decomposes touchpoints into atmospheric, technological, communicative, processual, employee–customer, customer–customer, and product interaction elements, offering a granular lens for diagnosis and design [

23].

Holistically, CX encompasses subjective, situated experiences that intertwine cognition and affect within social and physical contexts [

24]. To structure this complexity, several dimensional models have been proposed; Gentile et al. synthesize a comprehensive sixfold schema—sensorial, emotional, cognitive, pragmatic, lifestyle, and relational—that aligns closely with both experiential marketing and service-system logics of value co-creation [

25]. When we compare CX to UX, we draw on Lewis’s idea that CX is actually broader than UX. While UX focuses on how someone interacts with a specific product or service, CX encompasses the entire journey across all the company’s offerings. It examines how all these touchpoints work together over time, which makes it more complex and requires a different approach to manage [

6].

2.3. Tourist Experience

Consensus on the definition, dimensionality, evaluation, and managerial stewardship of TX remains elusive [

26]. TX can be framed as a domain-specific instance of CX—tourists are customers of tourism services, products, and systems—yet generic CX constructs do not always capture TX’s contextual richness (place-embeddedness, seasonality, multi-stakeholder co-presence, and destination sociocultural specificity).

Pine and Gilmore’s “4Es”—Entertainment, Educational, Escapist, and Esthetic—anchor TX in an experience-led economy. They emphasize the design of “memorable” episodes that leave a lasting impression in post-consumption memory. Therefore, we adopt the term Memorable Tourist Experience (MTE) as a variant of TX, highlighting its continuity with CX and UX while preserving the specific characteristics of tourism [

27]. Complementing this, Walls et al. outline a multi-level framework of factors that shape TX, which includes tourist dispositions, human interactions at the destination, and situational/contextual conditions. This framework emphasizes that experiences emerge from the interplay between the individual, social interactions, and the environment [

28]. At the field level, Ritchie and Hudson identify six research streams: conceptual studies focused on tourist behavior, methodological advances specific to tourism forms, and managerial perspectives on levels/types of experiences. This taxonomy clarifies how TX knowledge accumulates and identifies areas where gaps remain [

29]. From a methodological standpoint, Thompson’s critique of CX also applies to TX. Issues such as an over-reliance on quantitative instruments, limited integration of qualitative evidence for meaningful analysis, and weak connections between evaluation and design cycles hinder cumulative progress [

30]. Operationally, we adopt Ortiz et al.’s definition—TX as “the subjective perception experienced by tourists during their trip, which can be dynamic, depending on the stage of the trip they are in, and it occurs before, during, and after their interaction with the destination” [

31]—to make explicit its temporal staging and subjectivity. We find this temporality particularly useful for structuring evaluation efforts, as it forces researchers and managers to think explicitly in terms of pre-, during-, and post-visit touchpoints rather than isolated survey moments.

To make TX measurable without losing sight of the lived experience, we work with a concise, theory-guided structure. EMS represents affective responses such as enjoyment, feeling safe, or being pleasantly surprised. CTL reflects how visitors perceive their engagement with host traditions and community life. AUT refers to the sensed originality and identity of the place. ENT brings together recreational and cultural activities that spark interest and novelty. SVS describes the perceived quality of the physical setting, supporting infrastructure, and service delivery. These facets converge on a GEN, understood as an overall appraisal and synthesis of satisfaction, and on LOY, expressed in intentions to revisit and recommend the destination. Taken together, they are consistent with experiential and services literature, remain parsimonious for empirical modeling, and offer a practical lens for guiding destination design and the orchestration of touchpoints toward MTEs.

A clear narrative emerges from the preceding discussion, where emotions (EMS), contact with local culture (CTL), perceived authenticity (AUT), entertainment (ENT), and the qualities of the servicescape (SVS) converge into an integrated judgment of the visit (GEN). That judgment then anchors intentions to return and recommend (LOY). On this basis, we formally state the study’s hypotheses (H1-H6) and evaluate them in our structural model. Accordingly, H1–H6 are not stand-alone assertions but a compact formalization of this narrative, translating the conceptual account into the structural relations examined next.

3. Related Studies

Research on TX evaluation has progressed from broad conceptualizations to empirically specified models, scales, and structural equations that connect antecedents, holistic appraisal, and behavioral outcomes. Our overall assessment of this literature is positive but fragmented; many valuable pieces exist, yet they often overlap in terms of constructs, methods, and practical aims.

Conceptually, TX is framed as a holistic, multi-phase construct encompassing cognitive, affective, sensory, and conative responses throughout the journey, which motivates reflective, multi-item measurement and latent variable modeling in tourism contexts [

32]. Within this landscape, multiple TX models coexist rather than a single reference standard. Some emphasize memorable episodes (the MTE tradition), others highlight service-system attributes or place identity. Notably, the MTE line delineates the phenomenology of memorable encounters and formalizes it into validated instrumentation that links memorable attributes to satisfaction and intentions [

3,

33,

34]. Destination-specific works complement these perspectives by operationalizing facets such as authenticity, involvement, and service attributes in concrete urban and heritage settings, evidencing that reflective indicators can capture context-sensitive TX features with acceptable psychometric performance [

4,

35,

36].

The MTE instrument, introduced by Kim and colleagues, has become a key tool for assessing the affective and meaningful components of TX and examining their outcomes, such as satisfaction, likelihood of revisiting, and recommendations across various contexts [

3,

33,

34]. Parallel studies of destinations have adapted or expanded upon these instruments to include aspects like local culture cues, perceived authenticity, and servicescape elements. Typically, these studies employ confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to validate their measures before estimating structural relationships [

4,

35].

Recent research suggests that TX can be viewed as a specific form of CX, with practical evaluations relying primarily on multi-item scales that distill the experience into analyzable constructs [

26]. This body of work also highlights new priorities that have emerged post-pandemic—such as safety, inclusiveness, and sustainability—which many destinations are now integrating into broader assessments of servicescape and affective security, rather than treating them as standalone factors.

In terms of structural equation modeling (SEM) applied to TX, many studies go beyond simple correlations to investigate mediational pathways. In these frameworks, experiential factors feed into a global evaluation, which in turn influences behavioral intentions. Here, CFA first establishes reliable measurement (including loadings and convergent/divergent validity), followed by SEM to quantify indirect effects and compare alternative path structures.

The MTE tradition often identifies emotions or meaningful experiences as key drivers of overall evaluations and customer loyalty. Simultaneously, research focused on destinations introduces elements like authenticity, engagement with local culture, and servicescape as sensitive design factors that primarily exert indirect effects via a holistic appraisal [

3,

4,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Within this extensive research landscape, prior studies centered on Valparaíso have developed a multi-stage process: defining the domain and constructing an item pool, refining content validity through expert judgment, and gathering city-level survey data using reflective indicators mapped to actionable management strategies [

37,

38]. A subsequent study has reported a post-pandemic TX scale, offering practical insights that directly inform destination design and guide the specifications for this study’s CFA/SEM approach [

5].

Our research continues this trajectory by consolidating five key antecedent factors (Experiential Management Strategies, Cultural Touchpoints, Authenticity, Engagement, and Service Value) linked to a global appraisal and, ultimately, to customer loyalty. This approach aligns the modeling practices (scales + SEM) of TX with the prevailing body of evidence while remaining sensitive to the specific contexts of different destinations [

5,

26].

4. A Scale for Evaluating TX

Building on a post-pandemic TX scale previously developed and validated for Valparaíso [

5] and on the broader service science, CX, and tourist experience literature [

5,

17,

19,

26,

37,

38]. This refinement preserves the original theoretical backbone while focusing on stable, managerially actionable facets of TX [

5,

13]. We retain a parsimonious set of latent dimensions that concentrate the most stable and theoretically grounded sources of variation in tourist experience and loyalty. Specifically:

Emotions (EMS) represent the affective core of the experience, identified as central drivers of memorable and meaningful tourism experiences and global evaluations [

3,

32,

33,

34].

Local Culture (CTL) reflects immersion in local traditions, everyday life, and resident interactions, consistent with evidence that culturally embedded contact and social authenticity enhance distinctiveness, involvement, and perceived value [

4,

29,

35,

36].

Authenticity (AUT) operationalizes perceived genuineness and coherence of the destination’s cultural, historical, and symbolic attributes, which prior work links to deeper involvement and more favorable destination appraisals [

4,

32,

35].

Entertainment (ENT) captures the availability of engaging, hedonic, and participatory activities that enrich the experiential layer of the visit. This aligns with experiential marketing and CX perspectives, as such stimuli increase enjoyment and memorability, thereby reinforcing overall evaluations [

2,

19,

20,

28].

Servicescape (SVS) synthesizes the enabling environment (such as physical setting, cleanliness, safety, accessibility, information, and staff performance) recognized as a structural condition for positive experiences and perceived quality in both UX/CX and tourism-related environments [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

32].

This model consists of five key design-driven dimensions that serve as predictors of a GEN. The GEN is operationalized as a multidimensional construct that combines cognitive, emotional, and contextual evoked responses, which in turn drive LOY by revisiting intentions and recommendations. This approach is a theory-driven summary of the original scale designed for Valparaíso [

5], retaining its conceptual foundations while emphasizing dimensions that are robust, generalizable, and actionable for managers.

Unlike the previous version created post-pandemic, the specific dimension related to COVID-19 has been removed. This is because its indicators now largely overlap with standard expectations regarding cleanliness, safety, and emotional security, which are already addressed by the servicescape and emotional facets. Keeping this dimension would unnecessarily limit the model’s applicability over time and across different destinations.

Appendix A (

Table A1) presents scale’s items, in Spanish and English.

Sampling adequacy (n = 316) was excellent according to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test: the overall KMO was 0.969 for the full TX instrument, indicating substantial common variance relative to partial correlations and supporting the factorability required for the planned ordinal CFA/SEM.

Table 1 presents internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for the scale dimensions. Estimates are generally high. Most coefficients fall in the upper range typically considered acceptable for reflective scales, suggesting that the item sets cohere sufficiently for the subsequent CFA and SEM analyses.

Grounded in experience-economy and TX research, we connect each antecedent to GEN through established mechanisms: emotions drive holistic appraisals via affective assimilation; authenticity contributes meaning and coherence; servicescape shapes perceived quality and fluency; entertainment enhances hedonic value and memorability; local culture fosters involvement and place attachment. These mechanisms collectively predict stronger global appraisals and, in turn, loyalty. Accordingly, our hypotheses (H1–H6) derive from this literature-driven logic [

2,

3,

4,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. As seen in the structure in

Figure 1, our hypotheses are:

H1: Emotions (EMS) positively predict Global Perception (GEN). Research on memorable and experiential tourism shows that positive emotions experienced during the visit (such as enjoyment, excitement, or relaxation) strongly enhance global judgments of the trip and destination [

3,

32,

33,

34]. EMS is therefore modeled as a primary experiential driver of GEN.

H2: Local Culture (CTL) has a positive relationship with Global Perception (GEN). Contact with residents, local customs, and everyday culture contributes to perceived authenticity, involvement, and place attachment, which elevate overall evaluations of urban and heritage destinations [

4,

29,

35,

36]. CTL embodies this sociocultural embeddedness and is expected to exert a positive effect on GEN.

H3: Authenticity (AUT) positively predicts Global Perception (GEN). Perceived authenticity and coherence of the cultural and historical environment support deeper cognitive and affective engagement and strengthen the perceived meaningfulness of the visit [

4,

32,

35]. AUT is thus hypothesized to influence GEN positively as a key meaning-making dimension.

H4: Entertainment (ENT) has a positive relationship with Global Perception (GEN). Experiential and CX literature indicates that engaging activities, events, and hedonic stimuli enrich the experiential context, increase enjoyment, and contribute to favorable evaluations when aligned with visitor expectations [

2,

19,

20,

28]. ENT is therefore modeled as a reinforcing antecedent of GEN.

H5: Servicescape (SVS) positively predicts Global Perception (GEN). A well-designed servicescape underpins perceived quality and comfort in service and tourism settings [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

32]. SVS is expected to improve GEN by reducing friction and enabling fluent, reliable experiences.

H6: Global Perception (GEN) positively predicts Destination Loyalty (LOY). Empirical studies on tourist and customer experience show that overall evaluative judgments mediate the relationship between specific experiential attributes and behavioral intentions, including revisit and recommendation [

32,

33,

34,

36]. Accordingly, GEN is specified as the proximal determinant of LOY in our model.

5. Methodology

We conducted a theory-driven adaptation of existing TX items rather than de novo generation. Items were drawn from prior TX scale and urban-destination application [

5] and mapped to EMS, CTL, AUT, ENT, SVS, plus GEN and LOY. Both GEN and LOY were intentionally modeled with two reflective indicators to preserve parsimony. Under WLSMV, two-indicator latent factors are identified; nonetheless, we acknowledge the reduced content coverage relative to multi-item blocks and note this as a limitation.

In TX research, global appraisal and behavioral loyalty are often modeled with concise reflective indicators. This parsimony suits mediator roles in SEM and aligns with destination Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Our two-item GEN/LOY shows high loadings and AVE (

Appendix B), supporting this choice.

Wording was standardized to 5-point ordinal responses; additionally, a “Does not apply” option was included. “Does not apply” selections were treated as missing in analysis; the polychoric matrix and subsequent CFA/SEM used pairwise deletion. We followed a psychometric validation pathway; reliability (Cronbach’s α), sampling adequacy (KMO), ordinal CFA with WLSMV, and SEM for the structural model. Convergent/discriminant validity was assessed via AVE and HTMT.

As a robustness check, we re-estimated a structural variant adding direct paths from EMS, CTL, AUT, ENT and SVS to LOY while retaining GEN as mediator. Estimation, correlations and missing-data handling mirrored the main model, and models were compared via incremental fit indices. Model comparison relied on ΔCFI, ΔTLI, ΔRMSEA, and SRMR; the variant showed CFI 0.970 and RMSEA 0.073 with 90% CI 0.070–0.076.

We evaluated the TX measurement model using ordinal indicators and a structural layer that links antecedent facets of the tourist experience—EMS, CTL, AUT, ENT, and SVS—to GEN, which in turn predicts LOY. Estimation was performed in Jamovi (version 2.4.8) via SEMlj (version 1.2.3), which exposes lavaan within a reproducible point-and-click workflow in R [

39,

40,

41].

Participants were national and international tourists who had visited Valparaíso at least once. Data were collected via in-person intercept surveys in areas of touristic interest within Valparaíso and a parallel remote (online) questionnaire, from 316 participants; fieldwork took place in 2022. Both modes used the same Spanish instrument and the same eligibility screen. Responses from both modes were pooled for analysis [

5]. Recruiting tourists in situ meant working with fluctuating flows and varying willingness to participate; we regard the final sample as a realistic snapshot of visitors who were both reachable and willing to engage in a survey.

We employed a non-intentional, non-probabilistic sampling strategy (convenience intercepts and voluntary online participation). While this design precludes design-based inference, it is suitable for assessing measurement validity and estimating structural paths under realistic field conditions. This trade-off is acceptable in the tourism fieldwork, where tighter experimental control would likely distort the very experiences we seek to understand.

Given 5-point Likert responses [

42] and non-normality, we employed DWLS/WLSMV with robust standard errors, which is recommended for ordinal indicators to reduce bias in factor loadings and standard errors [

41,

43,

44]. Model adequacy was assessed against common thresholds—CFI/TLI ≥ 0.95 (good; ≥ 0.90 acceptable), SRMR ≤ 0.08, and RMSEA ≤ 0.05 (good), with RMSEA values between 0.05 and 0.08 treated as acceptable given model complexity [

45]. Among these indices, we personally find RMSEA and SRMR more informative for applied work, as they are somewhat less sensitive to sample size than incremental indices such as CFI and TLI. We identified the SEM by fixing the first loading of each indicator to 1.0 within its factor and freely estimating covariances among the antecedents. Indirect effects (Antecedent → GEN → LOY) were defined to capture the mediated influence on loyalty.

Data screening and model setup were done using Jamovi, resulting in a final sample of n = 316 valid cases (pairwise deletion for missing data). Although the n is modest for SEM, we judge it adequate for a model of this level of complexity, especially under DWLS, which is relatively forgiving of smaller samples. We chose Jamovi because its SEM module strikes a valuable balance between flexibility, potency, and reporting.

The model was estimated using DWLS with robust standard errors, relying on mean-adjusted, scaled, and shifted test statistics. Convergence was achieved after 282 iterations. The solver reported a minimal negative eigenvalue in the parameter covariance matrix; given the excellent overall fit and stable standardized solutions, we retained the model as empirically admissible. At the structural level, GEN was regressed on EMS, CTL, AUT, ENT, and SVS, and LOY on GEN, with all five antecedents allowed to intercorrelate. Indirect effects were computed as the product of each path to GEN and the path from GEN to LOY.

Relative to the earlier Valparaíso application, the current instrument omits the post-pandemic factor. By 2022, many COVID-19-specific concerns (e.g., hygiene protocols, crowding avoidance, perceived sanitary safety) had largely been absorbed into routine expectations about the servicescape and affective security. Removing this context-bound factor improved parsimony, identification, and cross-destination comparability without a discernible loss of explanatory power; where still salient, pandemic-related content is treated as embedded within SVS and EMS.

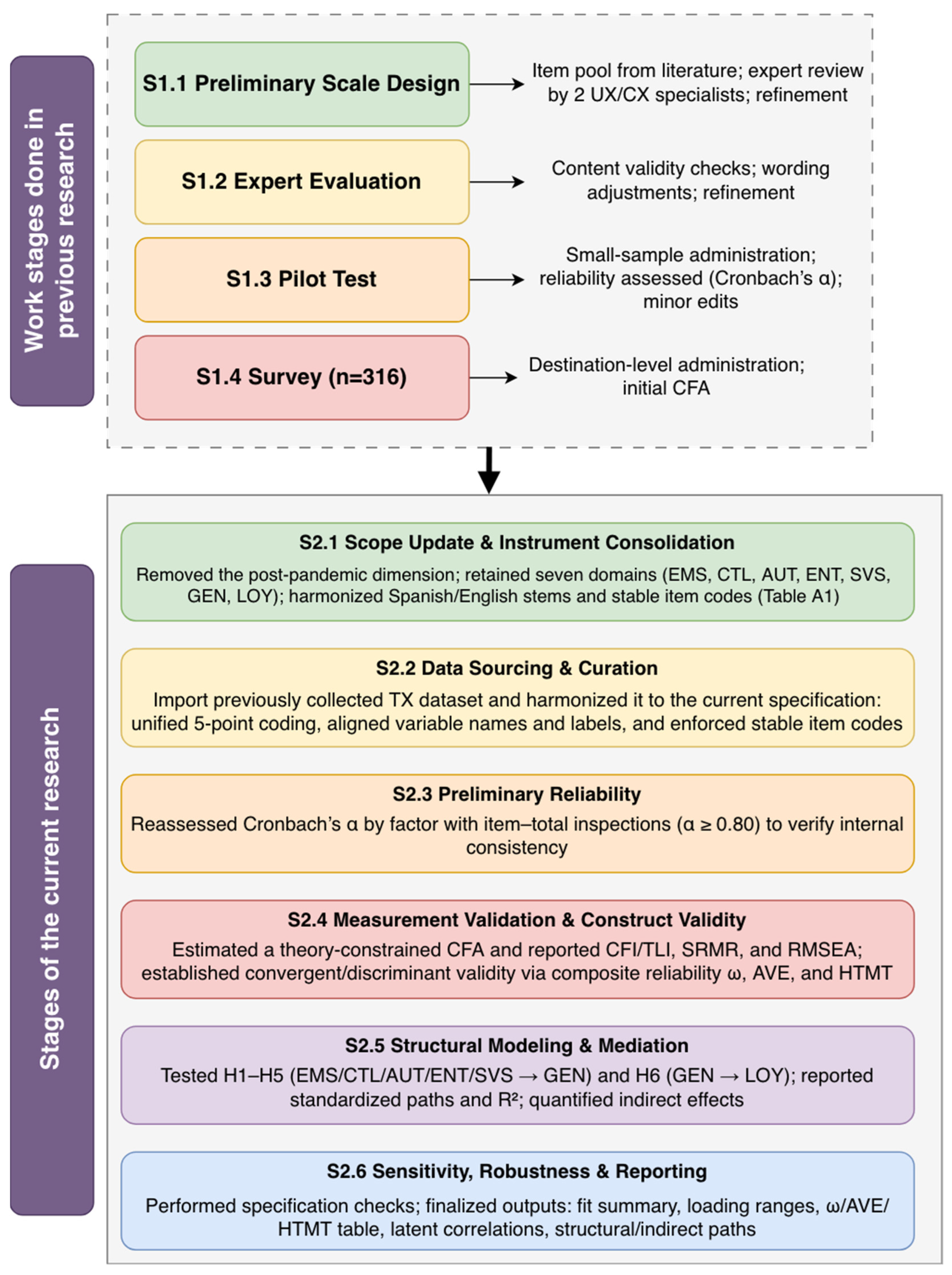

Figure 2 summarizes the research workflow in two tracks. The upper track (S1.1–S1.4) condenses the prior development of the TX scale, from literature-driven design and expert content evaluation to a pilot and a city-level survey, on which the present study relies [

5,

37,

38]. The lower track (S2.1–S2.6) details the current confirmatory and structural phase: scope update and instrument consolidation, data sourcing and curation from the previously collected dataset, screening and scale reliability (α), ordinal CFA with WLSMV to establish the measurement layer, construct validity via ω, AVE, and HTMT, and SEM to test the theory-driven mediation (Antecedents → GEN → LOY) with sensitivity checks.

6. Results

In

Table 2, scaled WLSMV indices indicated an adequate-to-good fit—CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.968, SRMR = 0.049, RMSEA = 0.073 [90% CI 0.070–0.076]. We regard this pattern as typical of large ordinal models and not indicative of substantive misfit.

The model explained a substantial share of variance in the two key latent outcomes, with R2 (GEN) = 0.787 and R2 (LOY) = 0.935. We consider these values high but plausible in light of the tightly integrated nature of TX antecedents and the proximal role assigned to GEN.

The direct-path variant showed essentially unchanged global fit. CFI was 0.970. GEN remained the dominant predictor of LOY, with a standardized effect of 0.680. Authenticity and servicescape contributed small additional direct effects to loyalty, whereas the remaining antecedents showed no unique contribution once GEN was retained.

As shown in

Table 3, the global appraisal of the destination was chiefly driven by EMS (β = 0.445,

p < 0.001), AUT (β = 0.271,

p < 0.001), and SVS (β = 0.241,

p < 0.001), while CTL and ENT did not carry unique explanatory power once the other facets were in the equation. LOY depended almost exclusively on GEN (β = 0.967,

p < 0.001), consistent with the idea that tourists synthesize multiple touchpoints into a singular evaluation that governs their return intentions (

Figure 3).

Beyond statistical significance, the EMS path to GEN is substantively large, translating into a strong indirect effect on loyalty through GEN (β_ind = 0.431, p < 0.001). EMS also exhibits high latent correlations with other experience facets (EMS–CTL = 0.898; EMS–AUT = 0.861; EMS–ENT = 0.804; EMS–SVS = 0.784), indicating that affect co-varies closely with cultural embeddedness, authenticity cues, activity design, and servicescape reliability. Together, these patterns support a holistic integration view in which affect amplifies the contribution of contextual and design elements to GEN.

As shown in

Table 4, loadings were uniformly high and statistically significant, supporting convergent measurement across factors; variation was expectedly broader in SVS given servicescape’s heterogeneity. We summarize per-factor ranges below.

As summarized in

Table 5, internal consistency and convergent validity are high across factors: composite reliability (ω) ranges from 0.931 (CTL) to 0.975 (AUT) for antecedents, with GEN = 0.954 and LOY = 0.950; AVE ranges from 0.726 (SVS) to 0.804 (AUT) for antecedents, and 0.963 (GEN) and 0.954 (LOY), all above the customary 0.50 threshold for reflective measures. Discriminant checks based on HTMTmax ≤ 0.93 (e.g., ENT–SVS = 0.922, GEN–LOY = 0.930) indicate strong but acceptable interfactor associations, consistent with a context where engaging activities and the servicescape are tightly coupled, and where a single global appraisal underpins loyalty intentions. Full item-to-factor loadings and the AVE computation per construct are reported in

Appendix B (

Table A2).

As shown in

Table 6, the first-order TX facets were strongly and positively intercorrelated (standardized), with notable correlations, including AUT–ENT = 0.899, ENT–SVS = 0.925, EMS–CTL = 0.898, EMS–AUT = 0.861, and AUT–SVS = 0.861, among others, indicating tightly coupled experiential components.

Because LOY is almost entirely explained by GEN (

Table 7), antecedents with significant effects on GEN also show substantial indirect effects on LOY: EMS (β_ind = 0.431,

p < 0.001), AUT (β_ind = 0.262,

p < 0.001), and SVS (β_ind = 0.233,

p < 0.001). Indirects for CTL and ENT were not significant.

Indirect effects via GEN were stable in the sensitivity variant, so total effects are driven primarily by the mediated channel, with only modest direct increments where noted.

7. Results Analysis

The empirical results present a coherent and encouraging picture of the TX mechanism under study: the measurement layer exhibits strong convergence and global fit, and the structural layer reveals a parsimonious pathway whereby affective, identity-laden, and environmental facets converge to form a single global appraisal that, in turn, almost entirely governs loyalty intentions. For us, this coherence between measurement and structure is reassuring; it suggests that the scale is not merely statistically neat but also narratively consistent with how tourism practitioners describe the loyalty process.

In the structural equations, EMS, AUT, and SVS emerge as the most consequential predictors of the global appraisal, with substantial standardized effects and significant explained variance in both the appraisal and loyalty outcomes; CTL and ENT, although strongly intercorrelated with the other antecedents, do not add unique predictive power once the more proximal levers are controlled, an outcome that is theoretically sensible in multivariate competition. The prominence of the emotional channel is entirely consonant with tourism research, which shows that positive affect underwrites satisfaction, memory formation, and evaluative judgments—mechanisms long documented for hedonic destinations and memorable tourism experiences [

3,

46,

47].

The significance of AUT aligns with classic and contemporary accounts that tourists seek what they construe as “real,” whether through historically anchored cues or existential resonance, and that such recognition deepens reflection, learning, and post-visit attachment [

48,

49,

50].

SVS’s unique contribution is equally consistent with service-quality theory and destination studies. When tangible and intangible service elements (such as cleanliness, wayfinding, accessibility, and staff reliability) meet or exceed expectations, they stabilize perceptions, reduce friction, and elevate overall evaluations [

51,

52].

The strong mediation from global appraisal to loyalty aligns with evidence that satisfaction-like appraisals bridge the gap between experience quality and behavioral intentions—return, recommendation, and advocacy—observed across destinations and segments [

53,

54,

55,

56].

The non-significant unique effects of ENT and CTL should not be read as irrelevant; instead, they reflect collinearity with affect and authenticity in destinations where engaging activities and cultural resonance co-occur with emotional uplift and identity cues, a complementarity anticipated by the Experience Economy’s entertainment/engagement logic and its tourism adaptations [

57,

58,

59,

60].

In this light, our findings do not overturn but refine prior propositions: emotions, authenticity, and servicescape are the proximate, high-yield levers for lifting the global appraisal, while cultural immersion and entertainment co-produce the same uplift through shared variance with those levers.

8. Discussion

Three antecedents positively and significantly predicted GEN, but their contributions were not uniform. Affective resonance and meaning-making (EMS, AUT) exerted the most decisive influence, indicating that how travelers feel and whether they perceive encounters as “authentic” anchor post hoc evaluations. From our point of view, this confirms that what ‘sticks’ in tourists’ minds is less a checklist of features and more a felt sense that the destination made emotional and symbolic sense to them.

Our analysis treats EMS as a reflective latent indicator of positive affect, not as a catalogue of discrete emotions. Consequently, we interpret variations in EMS through their contribution to GEN rather than as standalone emotional categories. The pattern EMS, AUT, SVS → GEN → LOY aligns with a cumulative appraisal view in which affect amplifies the influence of authenticity and servicescape on global judgments and loyalty intentions. The sensitivity analysis supports a predominantly mediated mechanism in which GEN integrates experiential inputs and governs loyalty intentions; small direct routes from authenticity and servicescape are consistent with complementary pathways but do not alter the substantive pattern.

Cultural embeddedness (CTL) and recreational stimulation (ENT) provided complementary lift by aligning expectations and sustaining engagement. At the same time, the enabling environment (SVS) fostered ease and trust, minimizing friction that could undermine overall appraisals. Mediation analyses confirmed that the indirect effects from EMS/AUT/SVS to LOY via GEN were statistically significant. Additionally, incorporating direct antecedent → LOY paths resulted in negligible incremental explanatory power and reduced coefficients. This suggests a predominantly mediational mechanism where various touchpoints coalesce into a single global appraisal, which, in turn, influences loyalty.

Sensitivity checks maintained consistent signs, magnitudes, and inferences. From a managerial perspective, we believe that the pathway is clear: prioritizing emotionally rich experiences (such as empathy, surprise, and delight), preserving and showcasing the destination’s authentic attributes, and ensuring a seamless servicescape (including cleanliness, navigation, safety, and accessibility) are high-yield strategies for enhancing GEN and, consequently, LOY.

For researchers, the model provides a statistically rigorous and easy-to-understand TX structure based on an existing proper ordinal CFA/SEM; in particular, it can be readily applied to testable instances other than this exemplar. Its scale specification makes it a candidate for cross-destination, cross-cultural validation, and multi-group invariance analysis and comparisons that explore how emotions, authenticity, culture, entertainment, and servicescapes combine to shape global appraisals and loyalty intentions.

Taken together, the model and the empirical results suggest that it is reasonable to read TX through the lens of both UX and CX. The patterns observed in emotions, servicescape, global appraisal, and loyalty are broadly consistent with what UX/CX studies report in other service and digital contexts. This provides us with grounds to treat TX not as an isolated construct, but as a context-specific expression of a more general experience framework that can be analyzed using similar concepts and tools.

However, several constraints qualify the interpretation and generalizability of these findings. The evidence is derived from a single urban coastal destination in Chile, using a non-probabilistic sample. Place-specific factors, such as seasonality, visitor demographics, heritage cues, mobility barriers, perceived safety, and pricing, may influence how antecedents interact and are integrated into GEN. We expect that in remote, nature-based destinations, the balance between servicescape and emotions might shift, whereas in major capitals, cultural touchpoints could play a more prominent, independent role.

Claims of broader applicability should, therefore, be assessed through multi-site replications and formal tests of measurement and structural invariance across key segments, utilizing criteria such as ΔCFI ≤ 0.010 to avoid over-interpreting trivial differences.

The cross-sectional, self-report design limits causal inference and raises concerns about common-method variance. Future studies would integrate procedural remedies with statistical checks and validate the GEN → LOY pathway using behavioral indicators to corroborate findings beyond perceptual data [

61].

Additionally, GEN and LOY were modeled using two reflective indicators each. However, this configuration is defensible given their strong communalities; it compresses content coverage and restricts the depth of reliability and validity diagnostics. Expanding these blocks with non-redundant items would enable stricter assessments following established CFA criteria [

62,

63,

64].

Strong correlations among antecedents, consistent with the ecological coupling of designed spaces, affective episodes, and identity cues, may attenuate unique regression paths, even when their joint influence is substantial, cautioning against overinterpreting isolated non-significant effects and motivating alternative specifications to better partition general from specific variance [

65,

66].

Methodologically, the use of DWLS/WLSMV is appropriate for five-point ordinal indicators; however, its fit indices are not directly comparable with those from ML/MLR studies. Slightly elevated RMSEA values in large ordinal models should be interpreted jointly with CFI, TLI, and SRMR rather than in isolation. In this study, missing data were handled via pairwise deletion when computing the polychoric matrix; this maximizes available information but estimates different bivariate correlations on slightly different subsamples, which can affect standard errors and global fit relative to listwise solutions. Where feasible, ordinal-aware multiple imputation pooled across WLSMV fits is preferable; as a robustness check, one may also estimate an MLR + FIML model treating indicators (or parcels) as continuous [

67,

68,

69].

9. Conclusions and Future Work

The study aimed to (i) confirm a theoretically grounded measurement structure for TX using ordinal CFA and (ii) quantify how specific facets of TX influence GEN and, subsequently, LOY through SEM. Both objectives were successfully achieved. We view this as an initial but solid step toward a more cumulative, methodologically transparent tradition of TX measurement in urban destinations.

The model demonstrated an adequate-to-good fit to the data, as indicated by the scaled WLSMV criteria (CFI/TLI ≈ 0.970/0.968; SRMR ≈ 0.049; RMSEA ≈ 0.073 [90% CI = 0.070–0.076]). It explains a significant amount of variance in both the global appraisal (R2 = 0.787) and loyalty (R2 = 0.935).

The most impactful factors for improving GEN were identified as EMS, AUT, and SVS. These facets also exhibit significant indirect effects on LOY, which reinforces the theoretical idea that tourists combine various experiences into a holistic judgment that conditions their intentions to return.

These findings provide a clear, evidence-based prioritization for destination managers and offer a statistically validated framework for researchers to use. For scholars, the results present a concise, empirically supported TX framework that aligns well with contemporary CX and TX literature, while being grounded in appropriate ordinal estimation methods. We encourage practitioners to view this framework not as a one-off diagnostic, but as a recurring lens for tracking how interventions in emotions, authenticity, and servicescape shape global perception and loyalty over time.

By removing the explicitly post-pandemic dimension and retaining five stable experiential factors, this scale serves as a promising foundation for cross-context replication, multi-group invariance testing, and comparative studies across different destinations and cultural settings, rather than being a one-time tool specifically for Valparaíso or Latin America. We hope that this choice makes the instrument more resilient to future shocks. Instead of tying it to a single crisis, it is anchored in enduring aspects of how visitors read and remember destinations.

For practitioners, the scale simplifies complex experiential constructs into a manageable diagnostic toolkit. It shows that investing in emotionally resonant experiences, perceiving authenticity, and maintaining a reliable servicescape is statistically proven to have a greater impact on shaping GEN and, consequently, loyalty, compared to spreading efforts across less decisive attributes. The five dimensions of the scale are closely linked to UN Tourism’s sustainability pillars. Therefore, the scale allows evaluating not only TX dimensions, but also sustainability aspects: resource-efficient, safe, and accessible operations (SVS); heritage stewardship and respectful host–guest relations (CTL and AUT); low-impact, locally rooted programming (ENT); and pro-social, pro-environmental engagement (EMS). A proper TX evaluation may certainly help sustainable tourism design.

Our structural pattern, EMS, AUT, SVS → GEN → LOY, identifies actionable levers that align with widely adopted sustainability pillars [

1]. SVS informs resource-efficient, safe, and accessible operations, which raise GEN and, indirectly, loyalty. AUT and CTL support heritage stewardship and respectful host–guest relations, helping destinations preserve identity while enhancing evaluations. ENT should privilege low-impact, locally rooted programming and temporal dispersion to reduce pressure on hotspots. EMS links to visitor well-being and pro-social/pro-environmental engagement. For policy and management, we recommend embedding GEN and/or LOY as KPIs in destination dashboards, setting targets, and evaluating interventions ex-ante and ex-post to track how improvements in servicescape, authenticity, and cultural interfaces shift global perception and loyalty [

1,

3,

7,

17,

34].

However, several limitations should temper direct generalizations. The evidence comes from a single urban coastal destination and a specific time frame, relies on self-reported perceptions, and has not yet been tested for invariance across cultures, market segments, or destination types. Therefore, we recommend applying this instrument in other destinations as a theoretically grounded, testable model rather than assuming it can be automatically transferred.

Future research should aim to validate the scale in diverse geographic and cultural contexts, assess measurement invariance and structural stability, and incorporate behavioral indicators (e.g., revisits, spending, referrals) to determine whether the GEN→LOY mechanism and the importance of EMS, AUT, and SVS remain robust and generalizable drivers of tourist loyalty. In our view, prioritizing servicescape reliability, safeguarding authenticity, and grounding programming in local culture are likely the most effective levers to lift GEN and, by extension, LOY. We also believe integrating GEN/LOY KPIs into sustainability monitoring could translate these results into actionable, trackable policies for urban destinations.