Assessing Ecosystem Health in Qinling Region: A Spatiotemporal Analysis Using an Improved Pressure–State–Response Framework and Monte Carlo Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

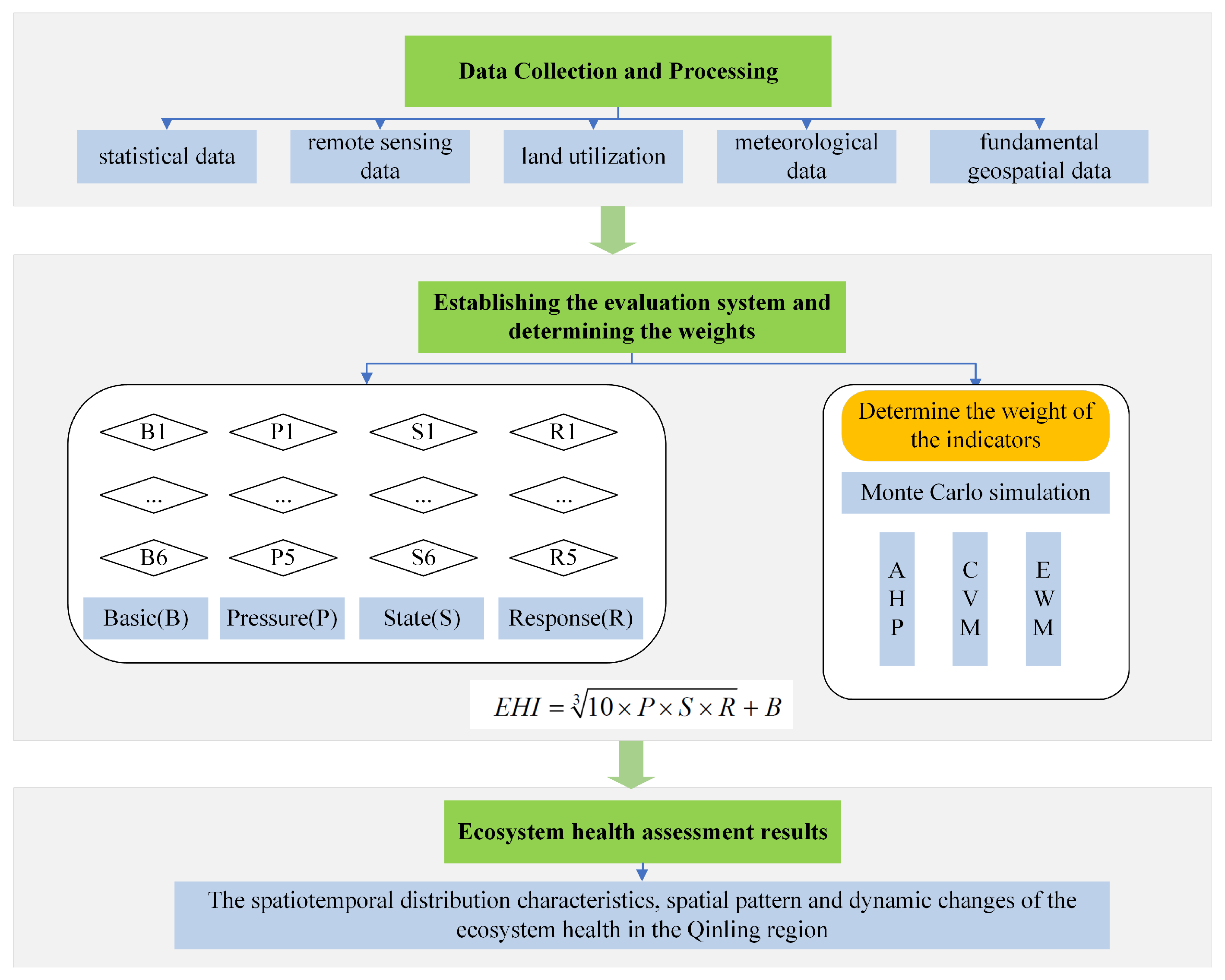

2. Materials and Methods

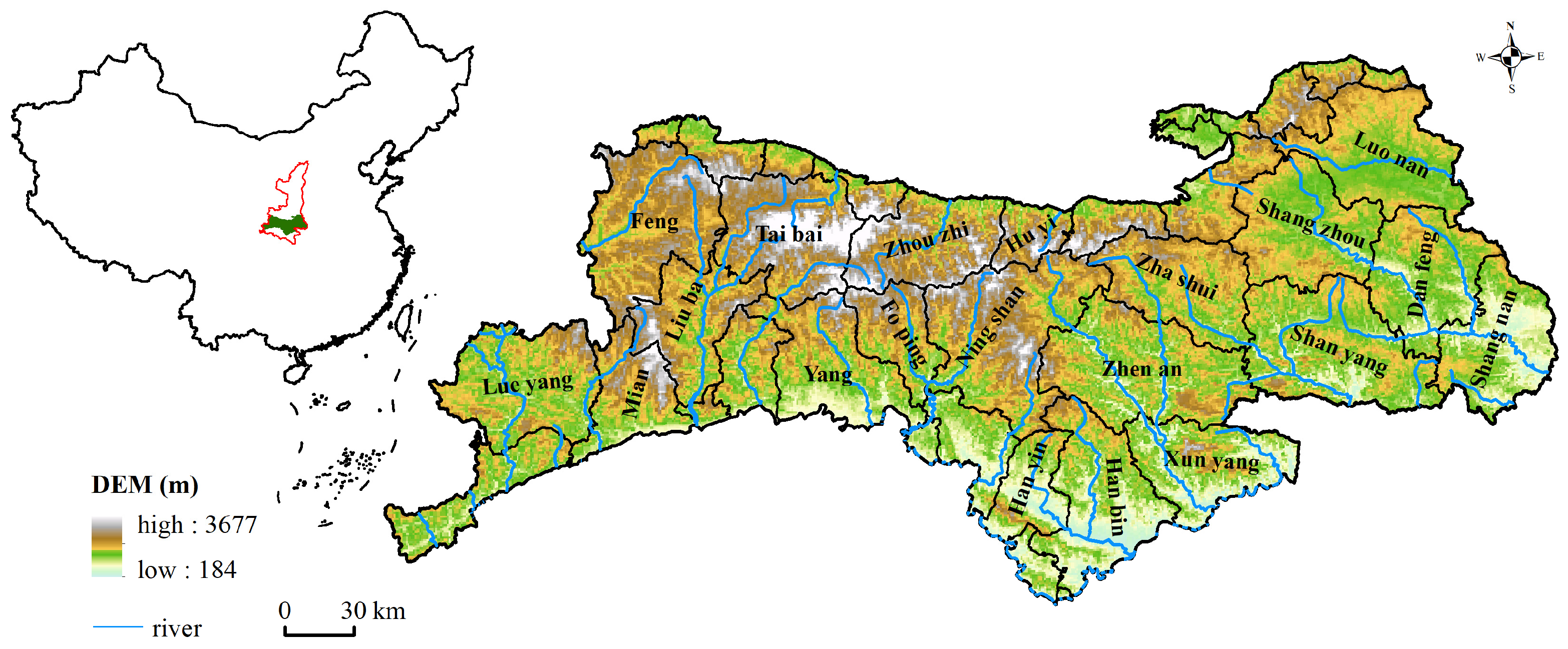

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

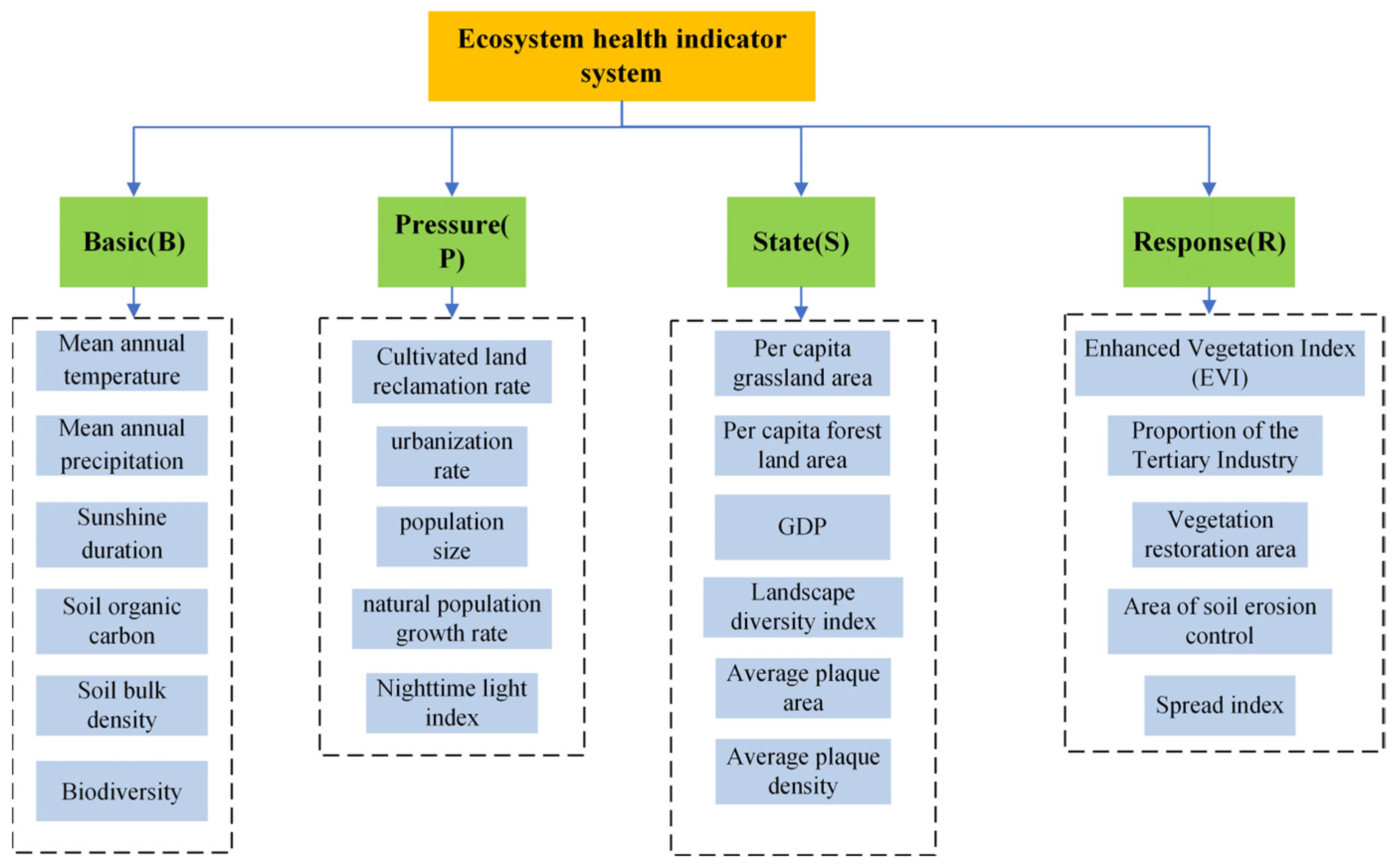

2.3.1. Construction of the Index

2.3.2. Determination of Evaluation Indicator Weights

- (1)

- Assume the ecosystem health evaluation model consists of evaluation objects and evaluation indicators. The initial matrix of the evaluation system is constructed as follows:

- (2)

- Calculate the proportion and entropy value of each indicator:

- (3)

- Calculate the weight of each indicator:

2.3.3. Calculation of the Ecosystem Health Index (EHI)

2.3.4. Other Methods

3. Results

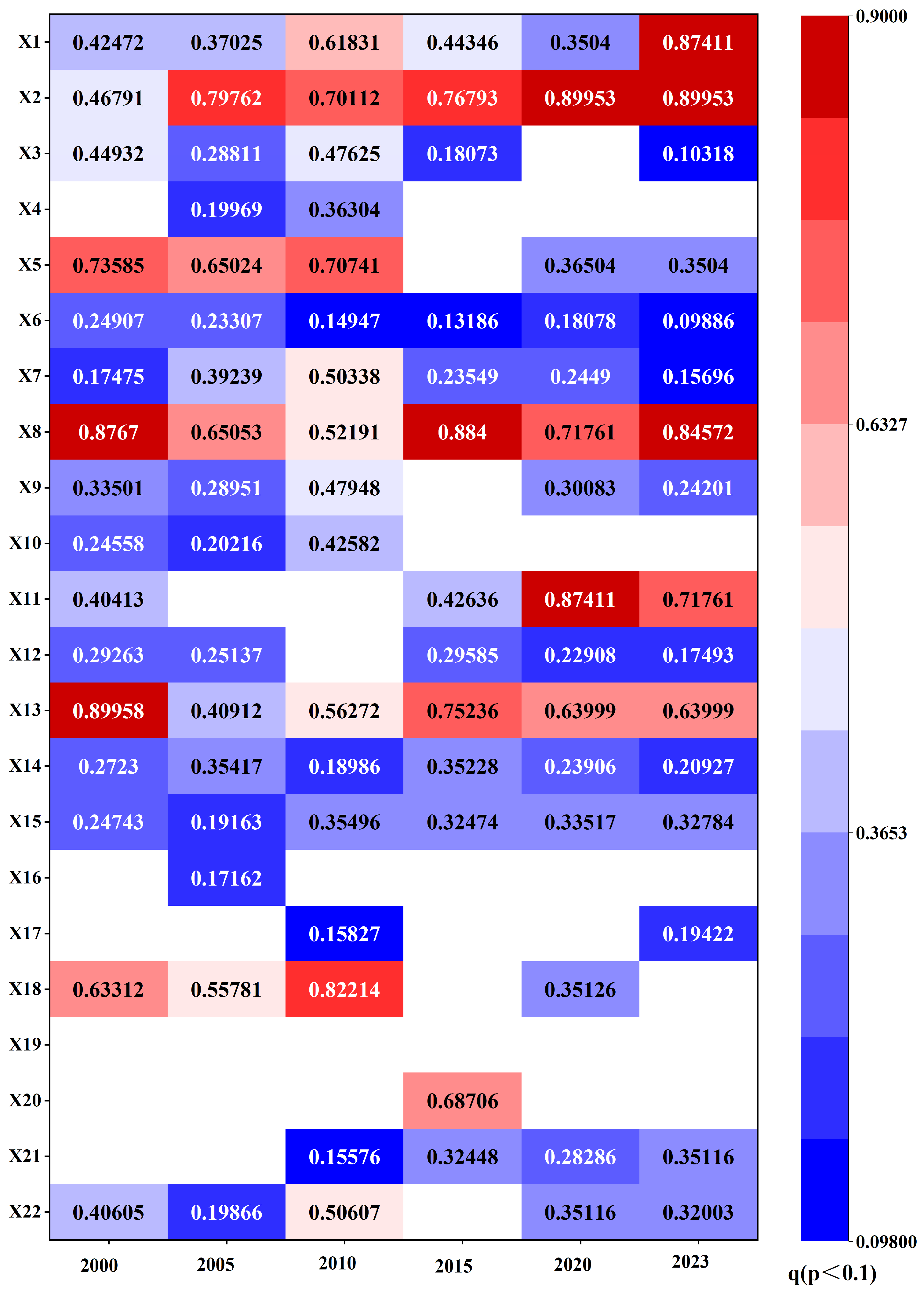

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Basic Indicators (B)

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Pressure Indicators (P)

3.3. Spatiotemporal Variation of State Indicators (S)

3.4. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Response Indicators (R)

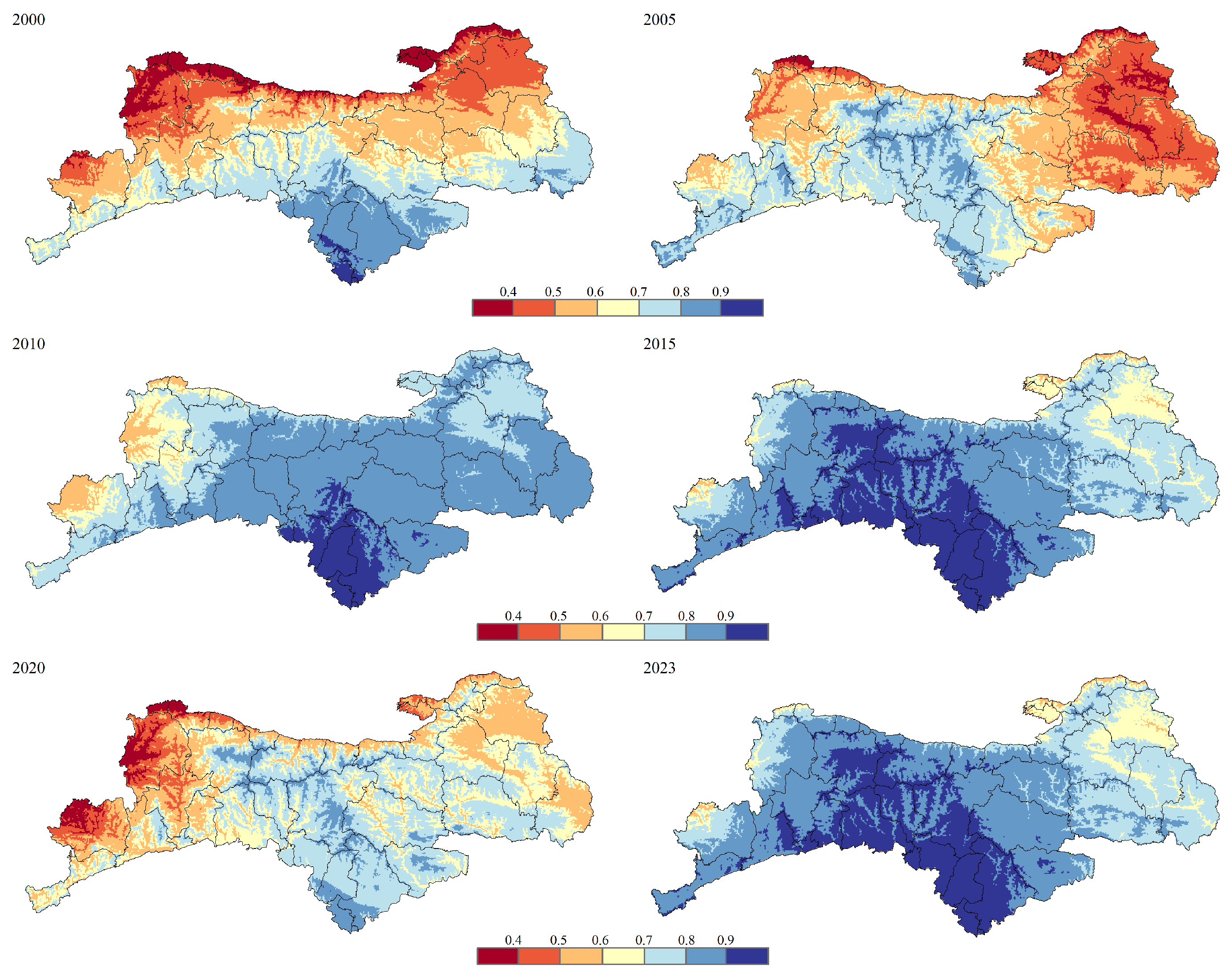

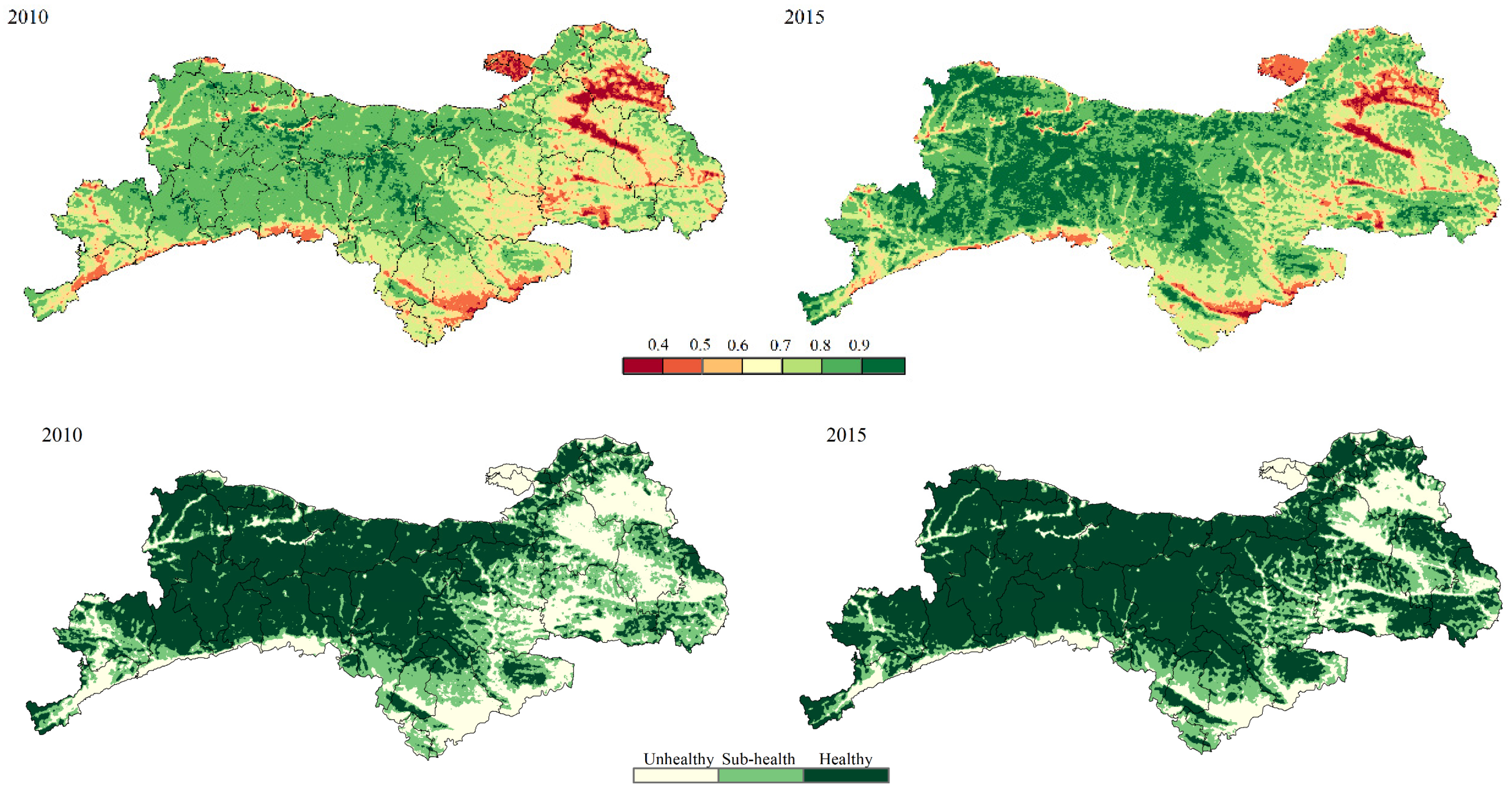

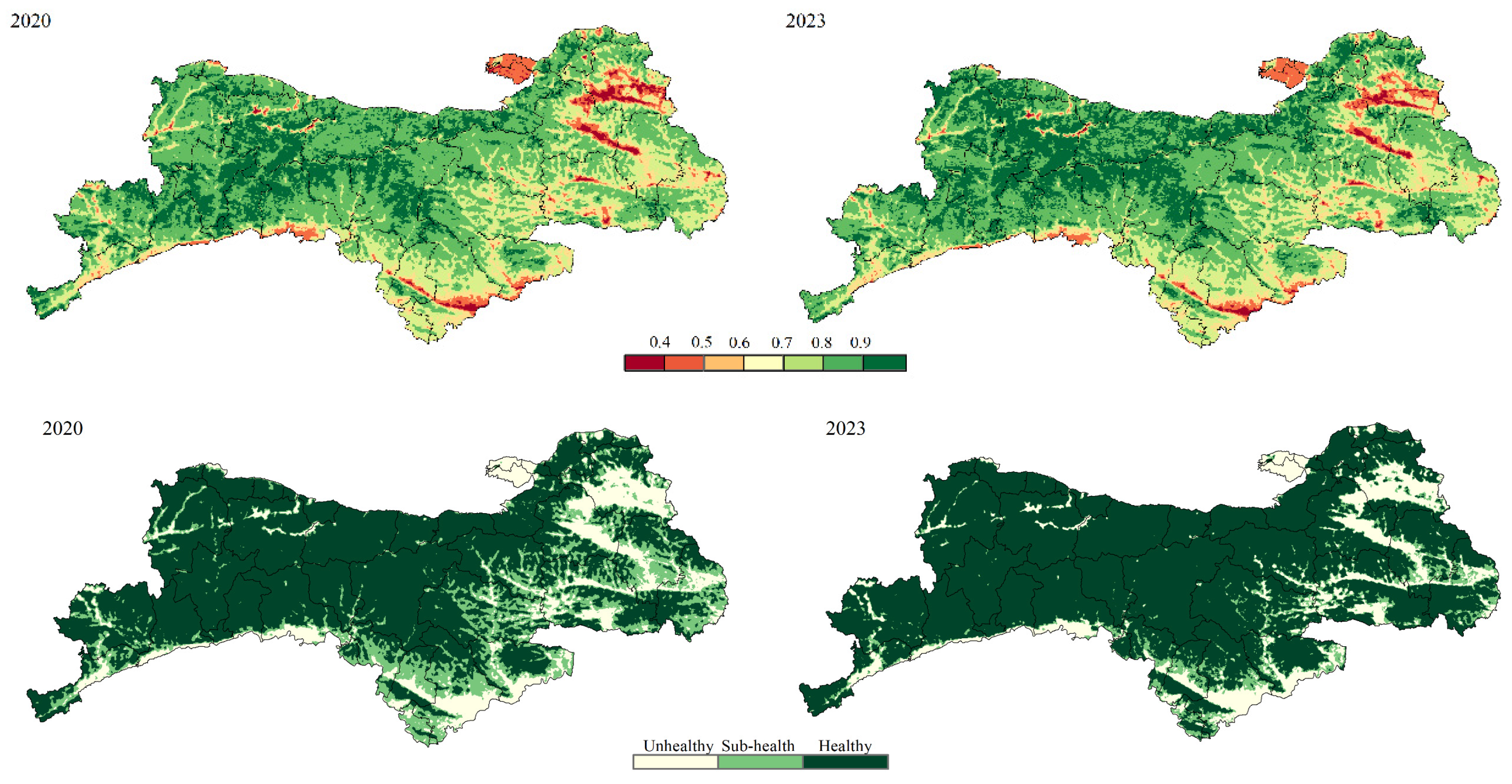

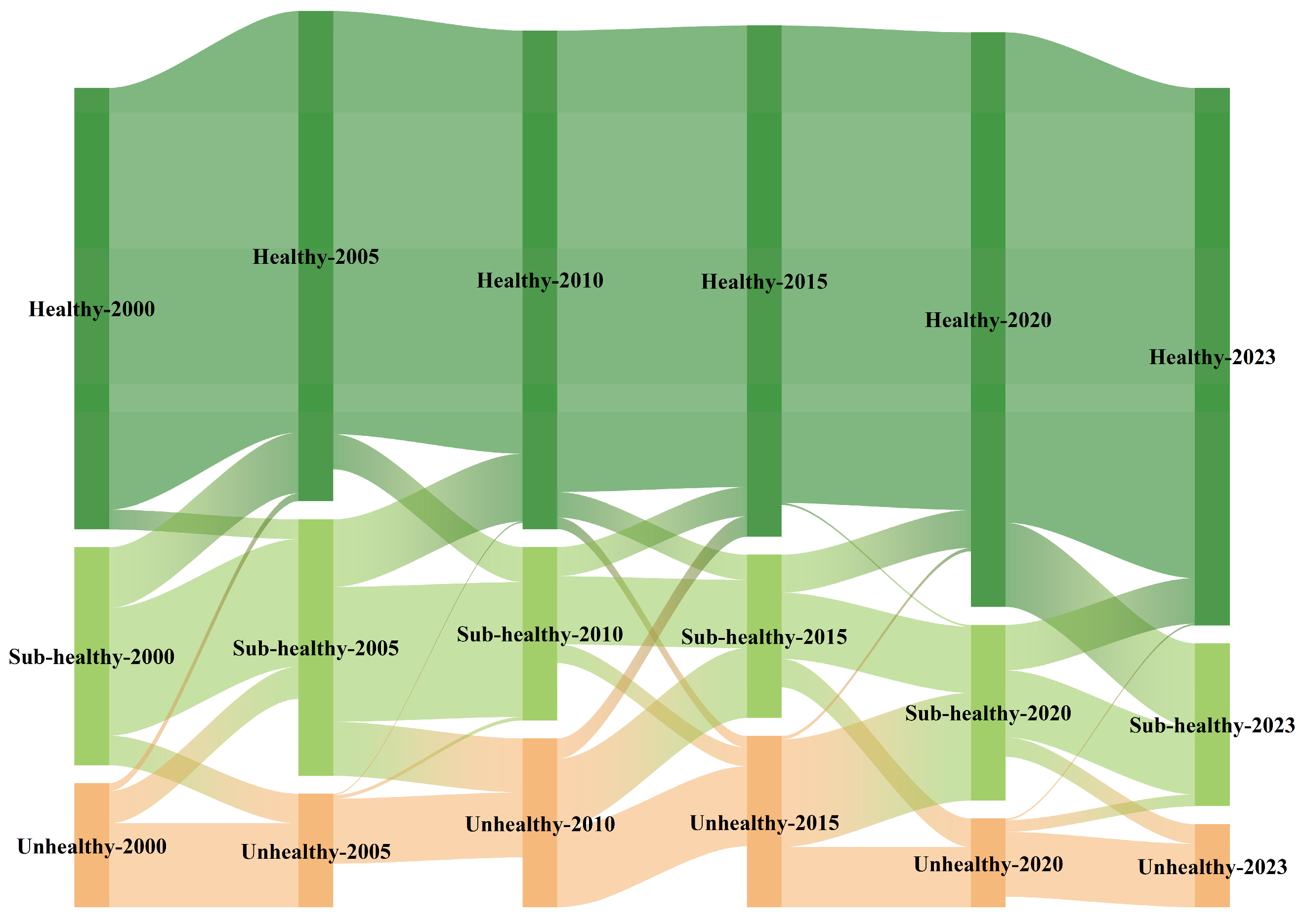

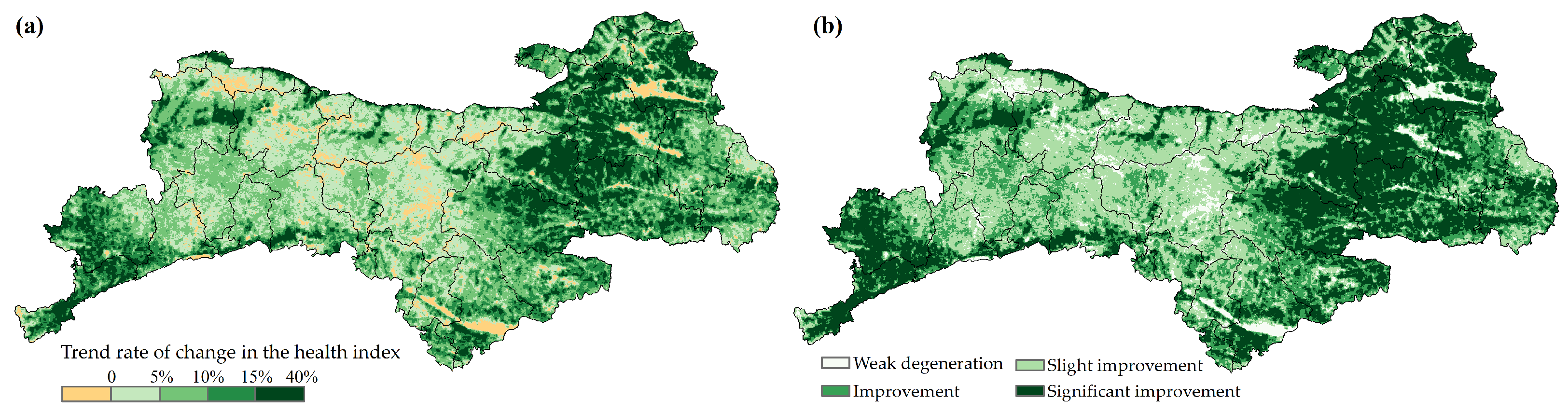

3.5. Spatial Change Rate and Dynamic Characteristics of the Ecosystem Health Index

4. Discussion

4.1. Innovation in the Research Framework and Improvement in Weighting Method

4.2. Driving Mechanisms of Ecosystem Health Evolution

4.3. Comparison with Related Studies

4.4. Policy Recommendations for Ecological Protection and Regional Sustainable Development

5. Conclusions and Prospects

- The innovation of the assessment system enhanced the scientific nature of the research: The addition of the “base layer” highlighted the decisive role of the natural background in the fragile mountainous ecosystem; the probability weighting method reduced the subjectivity and uncertainty of traditional weighting, providing a methodological reference for similar regions.

- The overall ecosystem health improved: The regional health index rose from 0.723 to 0.916, and the area proportion of healthy grades increased from 60.17% to 68.48%, demonstrating significant achievements in ecological protection and restoration. Spatially, a stable “south–low, north–high” pattern emerged: The southern Hanjiang River Basin, affected by dense human activities and low landscape connectivity, lagged behind in health levels; the northern Wei River Basin, with better vegetation conditions and relatively less human pressure, had a better health status. Temporally, it experienced a phased evolution from “local significant improvement” in the early period (2000–2010) to “widespread recovery” in the later period (2010–2023).

- The dominant factors of the health pattern changed significantly over time: In the early stage, natural and land use factors were dominant; in the middle stage, urbanization pressure became prominent; in the later stage, a complex driving pattern emerged, intertwining natural climatic conditions and human activity intensity, revealing the complexity and phased nature of the driving forces in the human–land coupled system.

- It is recommended to implement differentiated ecological management strategies: The ecologically fragile southern Hanjiang River Basin should be prioritized for restoration, with control over urban expansion and construction of ecological corridors to enhance landscape connectivity; the northern Wei River Basin, with a better ecological background, needs to strengthen ecological supervision over mineral resource development and tourism activities to consolidate existing achievements. At the same time, the protective role of natural backgrounds such as water and heat conditions should be emphasized, and adaptive measures such as soil and water conservation should be incorporated into long-term ecological planning. In areas with low health levels, fragmented landscapes, and restricted natural conditions, priority should be given to the layout of ecological restoration projects to enhance the effectiveness of measures.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baloch, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Iqbal, K.; Iqbal, Z. The effect of financial development on ecological footprint in BRI countries: Evidence from panel data estimation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6199–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, H.Z.; Wang, H.Z.; Xu, H. The spatiotemporal evolution of ecological security in China based on the ecological footprint model with localization of parameters. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.H.; Liu, J.C.; Guo, Y.J.; Wang, H.M.; Gong, Z. Assessing the ecological sensitivity of the Northern Foothills of Qinling Mountains using DPSIRM and PLUS models. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Yin, C.; Liu, X.L. Habitat Quality and Degradation in the West Qinling Mountains, China: From Spatiotemporal Assessment to Sustainable Management (1990–2020). Sustainability 2025, 17, 9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, G.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Luo, J. Spatial pattern reconstruction of regional habitat quality based on the simulation of land use changes from 1975 to 2010. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Nie, J. Vegetation dynamics in Qinling-Daba Mountains in relation to climate factors between 2000 and 2014. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhu, L.; Miao, C. Landscape Fragmentation in Qinling-Daba Mountains Nature Reserves and Its Influencing Factors. Land 2021, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; Falegnami, A.; Meleo, L.; Romano, E. The GreenSCENT Competence Frameworks. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, P.; Chen, W.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y. Linking ecosystem services and ecosystem health to ecological risk assessment: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Azizi, P.; Moghadasi, M. Land use change, urbanization, and change in landscape pattern in a metropolitan area. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, Q.; He, C.; Wu, J. Impacts of urban expansion on ecosystem services in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China: A scenario analysis based on the shared socioeconomic pathways. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Meng, X.L.; Wang, X.S.; Xiong, J.; Xu, Z.L. Spatiotemporal Changes and Driving Factors of Ecosystem Health in the Qinling-Daba Mountains. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hou, P.; Jiang, J.B.; Xiao, R.L.; Zhai, J.; Fu, Z.; Hou, J. Ecosystem Health Assessment of Shennongjia National Park, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.Y.; Wang, N.; Yu, L.; Guo, Z.H.; He, T.M. Spatial Distribution of Water Risk Based on Atlas Compilation in the Shaanxi Section of the Qinling Mountains, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Lin, D.H.; Xie, J.Y.; Wang, Y.K. A novel approach for modeling and evaluating road operational resilience based on pressure-state-response theory and dynamic Bayesian networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Li, C.J.; Zhou, W.X.; Liu, Y.X. Fuzzy assessment of ecological security on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau based on Pressure–State–Response framework. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Wu, T.X.; Wang, S.D.; Yang, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, M.Y.; Zhao, Y.T. Ecological safety assessment and analysis of regional spatiotemporal differences based on Earth observation satellite data in support of SDGs: The case of the Huaike River Basin. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.C.; Li, B.; Nan, B. An analysis framework for the ecological security of urban agglomeration: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.N.; Tang, B.T.; Li, Z.S.; Zhang, L.W.; Jiao, L. Assessing the spatiotemporal changes and drivers of ecological security by integrating ecosystem health and ecosystem services in Loess Plateau, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 35, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.M.; Li, Z.T.; Yuan, M.J.; Fan, C.; Xia, B.C. Spatial differentiation of ecological security and differentiated management of ecological conservation in the Pearl River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Bao, Y.B.; Xu, J.; Hua, A.; Liu, X.P.; Zhang, J.Q.; Tong, Z.J. Ecological security evaluation and ecological regulation approach of East-Liao River basin based on ecological function area. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Q.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, H.F.; Wu, K.N. Identification of ecosystem service bundles and driving factors in Beijing and its surrounding areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.R.; Zhu, L.K.; Meng, J.J. Fuzzy evaluation of the ecological security of land resources in mainland China based on the Pressure-State-Response framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Cao, B.; Dong, C.; Dong, X. Mount Taishan Forest Ecosystem Health Assessment Based on Forest Inventory Data. Forests 2019, 10, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zheng, Z.C.; Qin, Y.C.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving force of ecosystem health in an important ecological function region in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Cai, Y.L. Integrating ecological risk, ecosystem health, and ecosystem services for assessing regional ecological security and its driving factors: Insights from a large river basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.F.; Hou, K. Research on the progress of regional ecological security evaluation and optimization of its common limitations. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.R.; Xie, H.; Yue, W.N.; Zhang, L.X.; Yang, Z.F.; Chen, S.H. Urban ecosystem health evaluation for typical Chinese cities along the Belt and Road. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 101, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.Q.; Yan, Q.W.; Wu, Z.H.; Li, G.E.; Yi, M.H.; Ma, X.S. A Study on the Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity and Driving Forces of Ecological Resilience in the Economic Belt on the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains. Land 2025, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wu, Y.F.; Niu, L.T.; Chai, Y.F.; Feng, Q.S.; Wang, W.; Liang, T.G. A method to avoid spatial overfitting in estimation of grassland above-ground biomass on the Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Fu, T.G.; Liu, J.T.; Liang, H.Z.; Han, L.P. Ecosystem Services Management Based on Differentiation and Regionali-zation along Vertical Gradient in Taihang Mountain, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xin, C.; Du, W.; Yu, S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals based on source analysis and Monte Carlo in the Lijiang River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 176, 113620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.L.; Yan, C.R.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.X. Long time series dynamic monitoring of eco-environmental quality in Shaanxi Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 554–568. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wang, X.F.; Zhou, C.W.; Zhou, J.T.; Tu, Y.; Sun, Z.C. Integrative analysis of ecosystem health, ecosystem services and species habitat suitability can enhance the spatial configuration of protected areas. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Z.; Li, N.; Zhang, M.; Miao, M. Bayesian Network Analysis: Assessing and Restoring Ecological Vulnerability in the Shaanxi Section of the Qinling-Daba Mountains Under Global Warming Influences. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, R.; Li, W. Using the Geodetector Method to Characterize the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Vegetation and Its Interaction with Environmental Factors in the Qinba Mountains, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Dong, W.; Huang, F.; Wang, H. Eco-environmental quality assessment of transition region between Qinling Mountains and Huanghuai Plain using Remote Sensing Ecological Index. Geocarto Int. 2025, 40, 2462480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, L.; Jiji, J.; Kong, Q.; Ni, Z.; Yan, L.; Pan, C. River Ecosystem Health Assessment Using a Combination Weighting Method: A Case Study of Beijing Section of Yongding River in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantashloo, A.; Shokoohi, R.; Torkshavand, Z. Monte Carlo simulation for human health risk assessment of groundwater contaminated with arsenic at an Iranian semi-arid region. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2025, 23, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Gui, Y. Enhancing health risk assessment for soil heavy metal (loid)s using a copula-based Monte Carlo simulation method. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 300, 118419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.J.; Kang, J.W.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal Changes and Driving Forces of Ecological Security in the Chengdu–Chongqing Urban Agglomeration, China: Quantification Using Health-Services-Risk Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, L.X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. Spatio-temporal Dynamic and Driving Factor Analysis of Ecological Environment Quality in Qinling Mountains. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 3720–3730. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, R.F.; Clarke, K.C.; Zhang, J.M.; Feng, J.L.; Jia, X.H.; Li, J.J. Spatial correlations among ecosystem services and their socio-ecological driving factors: A case study in the city belt along the Yellow River in Ningxia, China. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 108, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hai, X.; Shanguan, Z.; Deng, L. Driving Factors of Ecosystem Services and Their Spatiotemporal Change Assessment Based on Land Use Types in the Loess Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 311, 114835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Huang, X.T.; Ye, X.Y.; Pan, Z.; Wang, H.; Luo, B.; Liu, D.M.; Hu, X.X. County ecosystem health assessment based on the VORS model: A case study of 183 counties in Sichuan Province, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.H.; Pan, Z.Z.; Liu, D.F.; Guo, X.N. Exploring the regional differences of ecosystem health and its driving factors in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 673, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.J.; Yang, Q.Q.; Tong, X.H.; Chen, L.J. Evaluating land ecological security and examining its relationships with driving factors using GIS and generalized additive model. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.H.; Du, Q.Q.; Guan, Q.Y.; Tan, Z.; Sun, Y.F.; Wang, Q.Z. Ecological security assessment and pattern construction in arid and semi-arid areas: A case study of the Hexi Region, NW China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Lu, X.; Liu, B.Y.; Wu, D.T.; Fu, G.; Zhao, Y.T.; Sun, P.L. Spatial relationships between ecosystem services and socioecological drivers across a large-scale region: A case study in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.Z.; Gao, G.Y.; Fu, B.J. Spatiotemporal changes and driving forces of ecosystem vulnerability in the Yangtze River Basin, China: Quantification using habitat-structure-function framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.Y.; Gao, J.B. Investigating the compounding effects of environmental factors on ecosystem services relationships for Ecological Conservation Red Line areas. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4609–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.J.; Han, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, M.X. Spatial heterogeneity of watershed ecosystem health and identification of its influencing factors in a mountain-hill-plain region, Henan Province, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Construction and optimization of regional ecological security patterns based on MSPA–MCR–GA Model: A case study of Dongting Lake Basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, C.J.; Fu, B.J.; Li, Y.H.; Xiao, S.S.; Zhang, J. Determining critical thresholds of ecological restoration based on ecosystem service index: A case study in the Pingjiang catchment in southern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Das Chatterjee, N.; Dinda, S. Urban ecological security assessment and forecasting using integrated DEMATEL-ANP and CA-Markov models: A case study on Kolkata Metropolitan Area, India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Liu, S.L.; Dong, Y.H.; An, Y.; Shi, F.N.; Dong, S.K.; Liu, G.H. Spatio-temporal evolution scenarios and the coupling analysis of ecosystem services with land use change in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 681, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Dai, E.F. Spatial-temporal changes in ecosystem services and the trade-off relationship in mountain regions: A case study of Hengduan Mountain region in Southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, H.; Lacayo, M.; Liu, J.; Lei, G. Impacts of Land-Use and Land-Cover Changes on Water Yield: A Case Study in Jing-Jin-Ji, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.J.; Jia, X.; Han, L.; Liu, L.; Ren, K.; Ye, X.; Qu, Z.; Pei, Y.J. Soil characteristics and microbial community structure on along elevation gradient in a Pinus armandii forest of the Qinling Mountains, China. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2022, 503, 119793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.K.; Ding, Z.W.; Qin, W.; Cao, W.H.; Lu, W.; Xu, X.M.; Yin, Z. Changes in sediment load in a typical watershed in the tableland and gully region of the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2019, 182, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion Layer | Indicator Layer | A H P | C V | E W | Combined Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic 0.1175 | Annual Mean Temperature | 0.0536 | 0.0370 | 0.0300 | 0.0413 |

| Annual Precipitation | 0.0226 | 0.0286 | 0.0173 | 0.0235 | |

| Sunshine Duration | 0.0354 | 0.0217 | 0.0100 | 0.0238 | |

| Soil Organic Carbon | 0.0142 | 0.0195 | 0.0081 | 0.0146 | |

| Soil Bulk Density | 0.0091 | 0.0123 | 0.0032 | 0.0087 | |

| Biodiversity | 0.006 | 0.0102 | 0.0022 | 0.0056 | |

| Pressure 0.414 | Cultivated Land Reclamation Rate | 0.0862 | 0.0162 | 0.0056 | 0.0399 |

| Urbanization Rate | 0.0196 | 0.0436 | 0.0400 | 0.0315 | |

| Total Population | 0.0606 | 0.0597 | 0.0755 | 0.0676 | |

| Natural Population Growth Rate | 0.0136 | 0.0587 | 0.0745 | 0.0365 | |

| Nighttime Light Index | 0.1189 | 0.0632 | 0.0850 | 0.0941 | |

| State 0.281 | Per Capita Grassland Area | 0.0287 | 0.0541 | 0.0625 | 0.0446 |

| Per Capita Forest Area | 0.0418 | 0.0042 | 0.0004 | 0.0215 | |

| GDP Per Capita | 0.0069 | 0.0497 | 0.0522 | 0.0307 | |

| Landscape Diversity Index | 0.0095 | 0.0676 | 0.0988 | 0.0483 | |

| Mean Patch Area | 0.0910 | 0.0247 | 0.0132 | 0.0466 | |

| Mean Patch Density | 0.0643 | 0.0221 | 0.0105 | 0.0343 | |

| Response 0.185 | Enhanced Vegetation Index | 0.0132 | 0.0822 | 0.1422 | 0.0105 |

| Proportion of Tertiary Industry | 0.0440 | 0.0164 | 0.0058 | 0.0377 | |

| Vegetation Restoration Area | 0.0198 | 0.0510 | 0.0570 | 0.0306 | |

| Soil Erosion Area | 0.0295 | 0.0270 | 0.0157 | 0.0137 | |

| Contagion Index | 0.0810 | 0.0158 | 0.0053 | 0.0246 |

| Framework Category | Specific Framework Name | Study Area |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pressure–State–Response Logic Frameworks | PSR (Pressure–State–Response) | Shaanxi Section of Qinling Mountains [14], Shanghai Expressways [15], Qinghai–Tibet Plateau [16], Huaihe River Basin [17,19] |

| Extended PSR | Yellow River Influenced Zone [25] | |

| 2. Ecosystem Attribute Assessment Frameworks | VOR (Vigor–Organization–Resilience) | Qinling-Daba Mountains [26], Shennongjia National Park [13] |

| VORS (Vigor–Organization–Resilience-Services) | Counties in Sichuan Province [45], China (Nationwide) [46] | |

| 3. Comprehensive Driving Force Analysis Frameworks | DPSIRM (Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses–Management) | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration [18] |

| DPSIRM | Northern Foothills of Qinling Mountains [3] | |

| 4. Vulnerability–Sustainability Framework | VSD (Vulnerability–Sustainability Diagnostic) | Shaanxi Section of Qinling-Daba Mountains [35] |

| 5. Structure–Function Correlation Framework | Habitat–Structure–Function Framework | Yangtze River Basin [47] |

| 6. Service-Oriented and Risk Assessment Frameworks | Health–Service–Risk Framework | Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration [41] |

| Health–Service–Risk Comprehensive Index | Hexi Region [48] | |

| 7. Social-Ecological System Service Frameworks | ER-EH-ESs (Exposure–Response–Ecosystem Health–Ecosystem Services) Framework | Huaihe River Basin [26] |

| Ecosystem Service Bundle Correlation Analysis | Ningxia Yellow River Urban Belt [43] | |

| 8. Direct Assessment Via Remote Sensing Indices | Remote Sensing Ecological Index (RSEI) | Qinling Region (Shaanxi Section) [42], Qinling-Huanghuai Plain Transition Zone [37], Shaanxi Province [33] |

| 9. Quantitative Assessment Via Process-Based Models | InVEST Habitat Quality Model | Western Qinling Region [4] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, J.; Jiang, Y. Assessing Ecosystem Health in Qinling Region: A Spatiotemporal Analysis Using an Improved Pressure–State–Response Framework and Monte Carlo Simulations. Sustainability 2026, 18, 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020760

Tian H, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Guo J, Jiang Y. Assessing Ecosystem Health in Qinling Region: A Spatiotemporal Analysis Using an Improved Pressure–State–Response Framework and Monte Carlo Simulations. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020760

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Hanwen, Yiping Chen, Yan Zhao, Jiahong Guo, and Yao Jiang. 2026. "Assessing Ecosystem Health in Qinling Region: A Spatiotemporal Analysis Using an Improved Pressure–State–Response Framework and Monte Carlo Simulations" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020760

APA StyleTian, H., Chen, Y., Zhao, Y., Guo, J., & Jiang, Y. (2026). Assessing Ecosystem Health in Qinling Region: A Spatiotemporal Analysis Using an Improved Pressure–State–Response Framework and Monte Carlo Simulations. Sustainability, 18(2), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020760