Abstract

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) are crucial for mitigating flood risks in vulnerable ecosystems, yet their effective application remains inconsistent. This study synthesises global literature to systematically map EIA methodologies, evaluate the extent of hydrological integration, and analyse the evolution of practices against policy frameworks for flood-prone areas. A scoping review of 144 peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, and one book chapter (2005–2025) was conducted using PRISMA protocols, complemented by bibliometric analysis. Quantitative findings reveal a significant gap where 72% of studies lacked specialised hydrological impact assessments (HIAs), with only 28% incorporating them. Post-2016, advanced tools like GIS, remote sensing, and hydrological modelling were used in less than 32% of studies, revealing reliance on outdated checklist methods. In South Africa, despite wetlands covering 7.7% of its territory, merely 12% of studies applied flood modelling. Furthermore, 40% of EIAs conducted after 2016 excluded climate adaptation strategies, undermining resilience. The literature is geographically skewed, with developed nations dominating publications at a 3:1 ratio over African contributions. The study’s novelty is its systematic global mapping of global EIA practices for flood-prone areas and its proposal for mandatory HIAs, predictive modelling, and strengthened policy enforcement. Practically, these reforms can transform EIAs from reactive compliance tools into proactive instruments for disaster risk reduction and climate resilience, directly supporting Sustainable Development Goals 11 (Sustainable Cities), 13 (Climate Action), and 15 (Life on Land). This is essential for guiding future policy and improving EIA efficacy in the face of rapid urbanisation and climate change.

1. Introduction

The accelerating pace of urbanisation, along with the degradation of wetlands and settlement into the floodplains, has exacerbated global flood disasters, particularly in developing countries like Sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. Wetlands are critical for flood mitigation and biodiversity but are increasingly compromised by infrastructure development and often driven by economic priorities over environmental safeguards [3]. This phenomenon has become more evident in South Africa, where recurrent floods in regions such as KwaZulu-Natal have highlighted systemic failures in land-use planning and enforcing Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) [4]. Despite the EIAs being globally recognised as a fundamental tool for environmental management since their inception under the US National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969 and the fact that they have evolved from a conservation to a sustainable development instrument, they face criticism for their inconsistent effectiveness worldwide [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Despite transitioning towards a more dynamic role in environmental governance, EIAs’ ability to address modern challenges like climate change depends on improved stakeholder engagement and context-sensitive approaches [2,13,14]. South Africa is amongst the countries that adopted EIAs, and despite their formal adoption under South Africa’s National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) 107 of 1998, the effectiveness of EIAs in flood-prone areas remains questionable, with critics pointing to weak hydrological integration, methodological inconsistencies, and gaps in policy implementation [15,16].

While EIAs are mandated to pre-empt environmental harm [17], their application in flood disaster risk contexts often lacks consistency, as seen in the persistent construction of human settlements in vulnerable areas [18]. According to the World Bank, reports of inadequate technical depth have resulted from the rapid proliferation of EIAs surpassing the ability for quality certification [19].

Even with post-apartheid reforms like NEMA, the EIAs in South Africa usually fall short in balancing long-term climate resilience with development demands [20]. South Africa’s EIAs frequently omit specialised hydrological assessments [18]. Areas such as informal settlements, which house 25% of Durban’s population, bypass EIA regulations entirely, exacerbating flood vulnerabilities [1]. Even in cases where EIAs are carried out, research reveals systemic flaws like methodological gaps, where checklist approaches are overused and GIS/spatial analysis is underutilised [17,19]. This approach disconnects policy and implementation, leaving NEMA’s strong framework compromised by a lack of enforcement, especially when integrating climate resilience [20,21]. Finally, the hydrological oversights show that, even though wetlands make up 7.7% of South Africa’s territory, only 12% of EIAs in floodplains incorporate flood modelling [4,22,23]. Despite existing case studies and policy analyses, a systematic review synthesising EIA methodologies, hydrological integration, and policy evolution in flood-prone contexts like South Africa remains absent. This study addresses this gap by evaluating EIA efficacy and proposing actionable improvements to strengthen EIAs as tools for climate adaptation and risk management, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 11 (Sustainable Cities), 13 (Climate Action), and 15 (Ecosystem Protection). By mapping methodologies, assessing hydrological considerations, and analysing policy frameworks, this review offers practical insights for decision-makers to enhance flood resilience and inform public policy and territorial planning

Aims and Objectives

This review aims to synthesise studies in the existing literature by mapping EIA methodologies, evaluating policies, and assessing hydrological considerations underpinning EIA efficacy. The objectives of the study were as follows:

- To evaluate the methodologies used to assess the effectiveness of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIAs) in flood-prone areas;

- To determine the extent to which hydrological impact assessments are integrated into the EIA process for developments in flood-prone zones;

- To analyse the evolution of Environmental Impact Assessment methodologies and their alignment with current policy frameworks.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the study’s materials and methodology and the rationale for their selection. The study’s statistical and bibliometric analysis findings are shown in Section 3. Section 4 examines the findings from a broad perspective on the function and efficacy of the EIA. A thorough explanation of EIA is then provided, along with current advancements in the effectiveness of the process and its function. A summary of the study’s findings, conclusions, suggestions, and administrative ramifications is given in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Information Sources

The study followed a standardised process, adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to conduct the scoping review as reported [24,25]. The review included peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters published between 2005 and 2025 that focused on Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) in flood-prone areas. Eligible studies examined methodologies, hydrological integration, or policy frameworks in relation to EIAs. Only English-language publications were considered. Exclusion criteria comprised non-peer-reviewed literature, grey literature, editorials, commentaries, and studies unrelated to EIAs in flood contexts. Studies were grouped for synthesis according to their thematic focus: (i) EIA methodological approaches, (ii) integration of hydrological assessments, and (iii) policy evolution and alignment. A systematic search was conducted across major electronic databases, namely Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, and Google Scholar, included due to their wide coverage of environmental and hydrological sciences. The reference lists of included papers were also checked to identify additional relevant studies. The initial search was performed in November 2024 and updated in April 2025.

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection

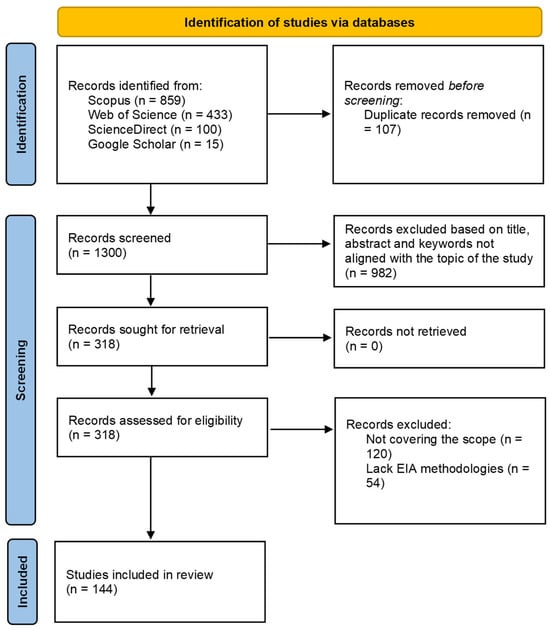

A keyword–Boolean strategy was applied to ensure comprehensive retrieval. Keywords included combinations of “Environmental Impact Assessment,” “flood-prone areas,” “hydrological integration,” “wetlands,” “floodplain,” “climate resilience,” and “policy evolution.” Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR”) were used to refine searches. Filters were applied to restrict results to 2005–2025 and English-language publications (See Supplementary Material). The temporal scope of this review (2005–2025) was deliberately selected to provide a contemporary analysis that captures pivotal shifts in the field; 2005 serves as a strategic starting point, chosen because it post-dates the widespread integration of geospatial technologies and the emergence of climate change adaptation as a central theme in environmental policy, enabling a robust examination of their evolution within EIA practice. Extending the end date to 2025 ensured the inclusion of the most current research and cutting-edge advancements, while the twenty-year span was sufficient for identifying significant methodological and policy trends without sacrificing relevance to present-day applications. The search yielded 1407 documents, which were imported into Rayyan software (v.1.4.3) for screening. After removal of duplicates, 1403 records remained. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers to exclude irrelevant studies. Full-text screening was then undertaken to confirm eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion among the review team. Automation tools (Rayyan’s duplicate detection) assisted in the process. Ultimately, 144 journal articles, 2 conference papers, and 1 book chapter met the inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates the review selection process, highlighting the systematic exclusion of ineligible or irrelevant studies while retaining those that fulfilled the study criteria. This rigorous screening ensured that only pertinent, high-quality studies were included in the final screening analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart PRISMA 2020 screening procedure (adapted from PRISMA [24]).

2.3. Data Collection Process and Data Items

Data extraction was undertaken using NVivo software (v.15). Two reviewers independently extracted data on study characteristics, methodologies, and outcomes related to EIA effectiveness, flood risk, hydrological assessment, and disaster mitigation. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus. No automation tools were used for data extraction. For outcomes, data were collected on (i) methodologies used in EIAs, including checklists, GIS, and hydrological modelling; (ii) inclusion of hydrological impact assessments (HIAs) and flood modelling; and (iii) policy integration and resilience measures. Other variables in data items included publication year, geographic focus, type of study (journal, conference, or book), and thematic emphasis. When information was missing or unclear, assumptions were made based on context, like regional focus inferred from authorship and case location.

2.4. Study Risk of Bias Assessment and Effect Measures

No formal risk of bias tool was applied because this was a scoping review. However, quality was indirectly assessed through eligibility filters such as peer-reviewed status, English language, and relevance to flood-prone EIAs. This review did not perform a meta-analysis; thus, no effect sizes like risk ratios were calculated. However, outcomes were summarised descriptively and thematically, highlighting prevalence and frequency trends such as the proportion of studies incorporating hydrological assessments.

2.5. Synthesis Methods

To determine their eligibility, the studies identified for synthesis were grouped thematically according to their methodological approaches, hydrological integration, and policy evolution. During data preparation, qualitative coding in NVivo (v.15) was employed to standardise diverse reporting styles, though the need to impute missing summary statistics was not applicable. The results were then tabulated and visualised using VOSviewer (v.1.6.20) to generate keyword co-occurrence and co-authorship networks, with additional figures created to display trends by year, method, and geography. The synthesis methods consisted of descriptive synthesis and bibliometric analysis; rather than performing a meta-analysis, frequency counts and co-occurrence mapping were used to provide insight into prevailing patterns. Any heterogeneity among the studies, such as differences in regional context or policy frameworks, was explored narratively instead of statistically. Finally, no sensitivity analyses were conducted, as they were deemed unnecessary given the scoping nature of the review.

3. Results

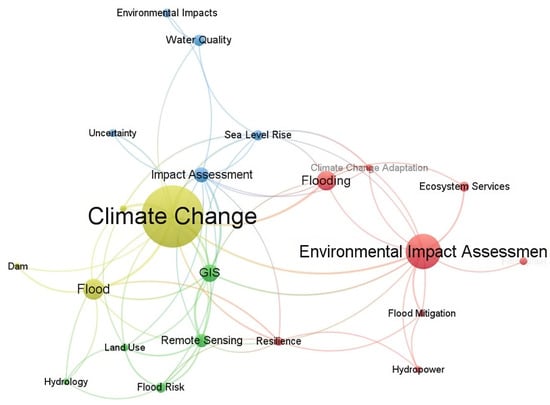

The final 144 published articles were subjected to a scoping review analysis for co-occurrence of the author’s given keywords using a VOS viewer version 1.6.20, a software tool for creating and visualising scoping review networks [3]. Figure 2 represents a network of twenty common keywords by the authors, which revealed that the top five keywords the writers gave were “floods”, “climate change”, “Environmental Impact Assessment”, and “flood.”

Figure 2.

Analysis of a network of authors’ top keywords (VOSviewer software version 1.6.20).

Node size indicates the frequency of occurrence, and the curves between the nodes indicate their co-occurrence. The shorter the distance between two nodes, the higher the number of co-occurrences of the two keywords. VOS viewer uses clustering algorithms to group similar items in a network with a colour spectrum ranging from blue (lowest score) to red (highest score) in terms of occurrence and co-occurrence [3]. The VOS viewer keyword co-occurrence analysis revealed critical thematic clusters in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and flood risk research, with “Environmental Impact Assessment” and “flooding” dominating the red cluster. This highlighted EIA’s centrality in flood-related studies. However, smaller node sizes for GIS and remote sensing indicated underutilisation of geospatial tools in EIA practice, a gap further evidenced by the weak co-occurrence between hydrology and core EIA keywords.

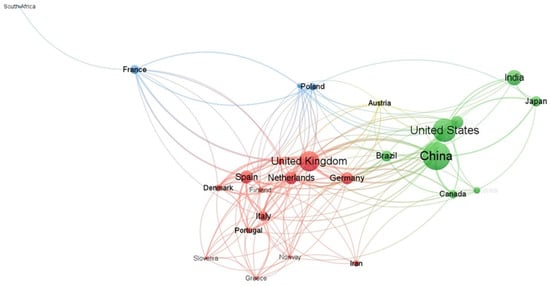

Figure 3 presents a bibliometric co-authorship analysis, revealing distinct global collaboration patterns in EIA and flood risk research. The network highlights dominant contributions from the US, China, and the UK, contrasted with fragmented participation from developing nations, particularly in Africa, reflecting disparities in research integration and resources.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the co-authorship network for the reviewed articles.

In the co-authorship network, node size represents a country’s publication frequency, with larger nodes such as the US, China, and the UK indicating higher research output. Connecting curves between nodes depict collaborative ties, where shorter curves denote more frequent collaborations. The co-authorship network in Figure 3 highlights a core–periphery divide in research collaboration. Dense international linkages dominate developed nations like the US, China, and the UK, while developing countries like India and Brazil often publish in isolation (80% single-country authorship). South Africa’s position as the sole African node with minimal intra-continental ties reflected broader knowledge import dependency, a key barrier to context-specific flood risk solutions. Smaller, isolated nodes like South Africa reflect limited international collaboration, while clustered groupings like those for European countries highlight regional collaboration patterns. This visualisation highlights disparities in global research engagement, with dominant hubs centralising knowledge production.

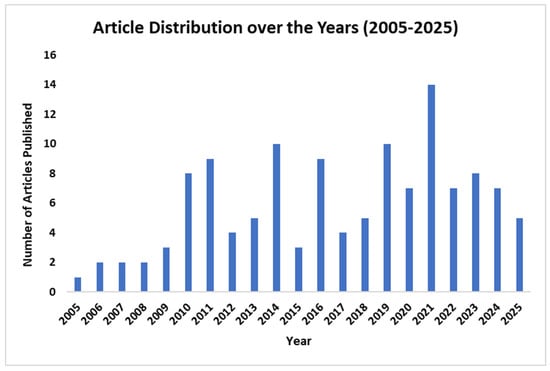

The article distribution analysis shown in Figure 4 reveals a marked increase in research output, with publication volumes doubling between 2020 and 2025, reflecting heightened focus on climate adaptation in EIA frameworks.

Figure 4.

Article distribution by year.

The longitudinal analysis depicted in Figure 4 revealed distinct phases in EIA and flood risk research. The formative period (2005–2015) saw steady growth, with climate change emerging as a predominant focus [26,27,28]. The expansion phase (2016–2020) coincided with policy frameworks and resilience concepts gaining traction [29,30], while the innovation period (2021–2025) reflected increased adoption of geospatial technologies [31,32,33,34,35]. Despite this progress, a persistent 3:1 publication ratio favouring developed nations highlighted significant disparities in research capacity.

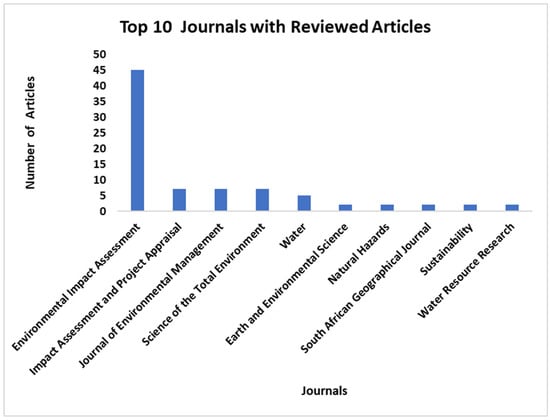

Figure 5 shows the top 10 journals of the analysed articles for this review. The analysis indicates dominance of specialised journals like Environmental Impact Assessment Review in EIA–flood risk research, alongside interdisciplinary and regionally focused publications, which reflects trends in policy and hydrological science integration.

Figure 5.

Top 10 journals with reviewed articles.

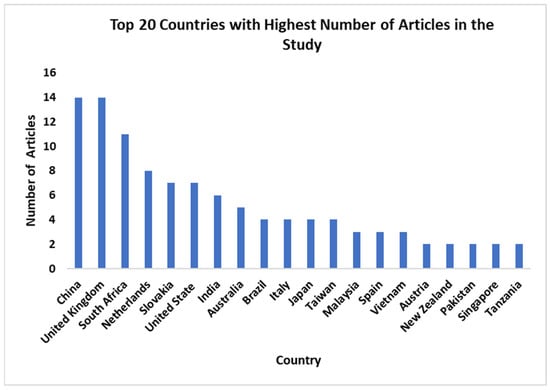

Figure 6 shows the top 20 countries with the highest numbers of articles in this study. The geographic distribution of articles highlights a core–periphery divide in knowledge production, where developed countries drive research agendas. In contrast, flood-vulnerable developing countries are engaged in less research regarding EIAs and hydrological science integration, hence exacerbating the implementation gap.

Figure 6.

Top 20 countries with the highest number of articles in the study.

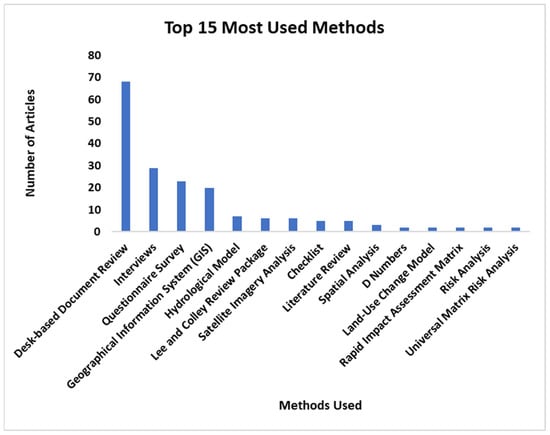

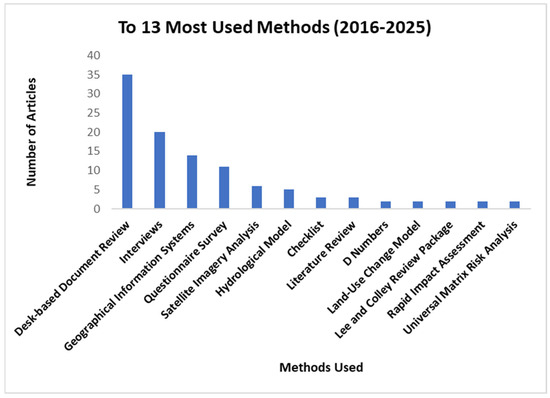

A methodological analysis of the top 15 most used methods in EIAs is presented in Figure 7, showing desk-based document review as the most dominant method, followed by interviews and questionnaire surveys.

Figure 7.

Most used methods across the included studies.

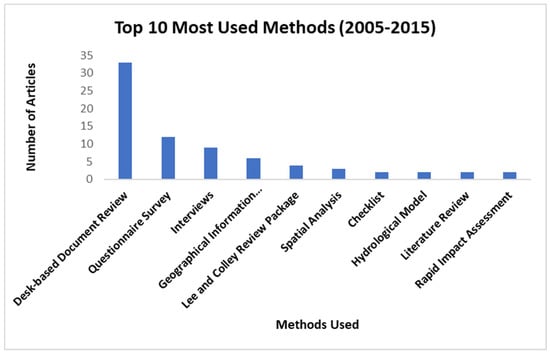

The findings demonstrate a progressive adoption of advanced technologies, including geographic information systems (GISs), remote sensing, and land-use change modelling. A temporal analysis was conducted to unearth methodological trends, examining prevalent methodologies from 2005 to 2015 (Figure 8) and 2016 to 2025 (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Top 10 most used methods (2005–2015).

Figure 9.

Top 13 most used methods (2016–2025).

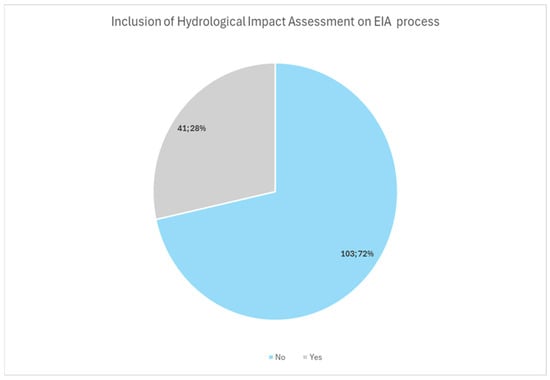

The methodological analysis in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 demonstrated an incomplete transition in EIA research approaches. Traditional qualitative methods like checklists and desk reviews declined by 40% between 2005 and 2015 and 2016–2025, while quantitative techniques like GIS and hydrological modelling gained prominence. Notably, hybrid methodologies that combined geospatial and hydrological approaches increased by 70% post-2016. However, persistent reliance on interviews and questionnaires (12–15 articles) reveals ongoing challenges in primary data collection, primarily in developing nations, as El Sayed and Salah [36] elaborated. Analysis of hydrological impact assessment incorporation in EIA processes (2005–2025) revealed only 28% of studies demonstrated successful integration, while the majority (72%) lacked hydrological assessment components, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Inclusion of hydrological impact assessment in the EIA process.

4. Discussion

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) represent a critical governance tool for identifying, avoiding, and mitigating risks in vulnerable ecosystems during the proposal of new development or projects; however, their effectiveness remains primarily inconsistent in developing countries [5,6,10,16,37,38,39,40]. This discussion synthesises the results through four lenses: (1) methodological limitations in existing EIA practices, (2) systemic neglect of hydrological factors, (3) policy–practice misalignment in EIA, and (4) the consequences for flood risk management and flood-prone area protection. By contextualising these results within the broader literature on flood disasters [1] to global comparisons of EIA efficacy [18,41], we will identify actionable pathways to bridge these gaps and enhance EIA’s role in sustainable development.

4.1. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Methodologies in Flood-Prone Areas

Environmental Impact Assessments have been recognised as an effective regulatory and protective tool for assessing and predicting the ecological effects of any project or development [17]. As indicated in Figure 7, the most dominant methods are desk-based document review prediction [42,43,44], interviews [21,45], questionnaire surveys [46,47,48,49,50], and GISs [18,21,31,45,51,52,53,54,55], with hydrological models [56,57,58,59,60] coming fifth. This study exposed a critical gap where 72% of reviewed EIAs lacked hydrological impact assessments (HIAs) despite operating in flood-prone contexts, as indicated in Figure 10. The minority (28%) that incorporated HIAs were predominantly from developed countries. This validated the keyword analysis findings regarding weak hydrology–EIA linkages and highlighted the urgent need for standardised hydrological integration in EIA protocols, especially in vulnerable regions. Additionally, keywords co-occurrence analysis indicated that floods, climate change, GIS, and remote sensing dominate the recent EIA literature. This strong connection suggests that the flood risk analysis in EIA cannot be assessed in isolation, but rather in conjunction with mitigation techniques, land-use changes, and climate variability [61,62,63,64].

Traditional EIAs have not offered a comprehensive view of the impact scenario for the prudent management of ecologically sensitive development projects due to high costs and poor planning [6,41,65,66,67,68]. The limitations of traditional EIA are now overcome by GISs, which produce an objective and comprehensible EIA [32,33,69]. Thus, the use of GISs is noted as the most effective approach to evaluate the environmental effects of road expansion projects [17,58,70,71].

The findings of this study highlight the critical role of EIA methodologies in flood-prone areas, particularly wetlands and floodplains. The scoping review analysis revealed that many EIAs continue to use desk-based document review, interviews, questionnaire surveys, and checklists, especially in regions with limited financial and technical resources. However, the current conventional EIA methodologies are costly, time-consuming, and occasionally vulnerable to subjective bias when evaluating the project’s environmental impact [72,73,74].

This study also revealed that between 2005 and 2025, GISs, remote sensing, and hydrological modelling were among the most frequently used techniques or methods in assessing environmental impact on proposed new developments or projects; some of these projects require flood risk analysis. These tools enable spatial analysis, flood risk mapping, and scenario-based assessments, which are essential for identifying vulnerable zones and guiding sustainable development.

However, the study also identified gaps in consistently applying these methodologies, particularly in developing regions like South Africa. While advanced techniques such as GISs and hydrological modelling are well-documented in the literature, their practical implementation in local EIA processes remains inconsistent [45,60,70,73,75]. Many EIAs in flood-prone areas still rely on qualitative checklists rather than quantitative risk assessments, limiting their ability to effectively predict and mitigate flood impacts [21,76].

Furthermore, the integration of climate change projections into EIA methodologies remains weak [60,77,78,79,80,81]. Given the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, EIAs must incorporate dynamic climate models to assess long-term flood risks. The lack of standardised guidelines for flood risk assessment within EIAs exacerbates these challenges, leading to variable outcomes in disaster resilience [2,3,13,64,82]. This disconnect between research trends and practical implementation raises concerns about whether cutting-edge methodologies are truly translating to on-the-ground resilience. For instance, in developed countries like the UK and Germany, studies such as those by Jiricka-Pürrer, Czachs, Formayer, Wachter, Margelik, Leitner, and Fischer [13] demonstrate successful integration of hydrological assessment (e.g., via GISs and remote sensing) into EIAs, leading to improved territorial planning and enhanced wetland protection by predicting flood scenarios and reducing social vulnerabilities in urban areas. In contrast, failures in high-risk regions of Africa and Asia, as reported by Hapuarachchi, Hughey and Rennie [11] in Sri Lanka and Aung, Fischer and Shengji [10] along the Belt and Road Initiatives, highlight how inadequate hydrological assessments resulted in ineffective flood risk mitigation, exacerbating wetland degradation and increasing vulnerabilities for informal settlements through poor land-use decisions

4.2. Evolution of EIA Methodologies and Policy Alignment

Since its official inception in the 1970s, the EIA process has undergone a significant transformation, progressing from basic compliance exercises to advanced, data-driven decision-support systems [18,21,37,39,43,66,83]. This evolution of EIA methodologies across the studies shows a notable trend, where there is a shift from traditional EIA methods such as questionnaires, interviews, checklists, and desk-based document review towards advanced tools or techniques such as GIS, remote sensing, and hydrological modelling. The shift indicates a broader transformation in the Environmental Impact Assessment processes, where EAPs are now adopting predictive, data-rich analyses over the descriptive assessments [41,84,85,86,87]. This systematic study showed clear methodological patterns across two significant time periods (2005–2015 and 2016–2025), especially when evaluating flood risks in ecosystems that are susceptible to flooding, such as flood-prone areas. Only 6% of research used hydrological modelling during the early years (2005–2015), when desk-based document review procedures (43%) and questionnaire surveys (28%) predominated. These traditional approaches, which frequently relied on qualitative descriptions devoid of sound scientific analysis, were helpful for identifying fundamental impacts but had limited capacity for thorough flood risk assessment [15]. The subsequent period (2016–2025) witnessed significant methodological advancements, reflecting growing recognition of climate change impacts and urbanisation pressures. GIS and remote sensing applications surged to 32% of the studies, which enabled precise floodplain mapping and cumulative impact assessments [19]. Hydrological modelling tools like HEC-HMS and SWAT gained substantial traction (24%), allowing for dynamic flood scenario analysis. In contrast, emerging technologies like GIS, remote sensing, hydrological modelling, and machine learning (12%) began enabling predictive flood risk analytics. These technical improvements were paralleled by enhanced stakeholder engagement approaches, with structured workshops (20%) replacing simpler questionnaire methods and demonstrating the field’s shift toward more scientific, participatory processes.

These methodological advancements have matched changes in policy frameworks. The transition from the Environmental Conservation Act 73 of 1989 to the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 in South Africa has indicated a critical change towards integrated environmental governance [16,18]. Since the promulgation of NEMA, a stricter public participation requirement, mandatory specialist studies (including hydrological assessments), and enhanced compliance monitoring have been introduced, aligning EIA processes with sustainable development goals and disaster risk reduction principles [18]. Recent trends emphasise strategic environmental assessments to be incorporated during the EIA process for broader policy integration and digital innovations like blockchain for real-time impact monitoring [88].

Despite these developments, there are still many hindrances to overcome. Inconsistent enforcement and the exclusion of informal settlements from regulatory monitoring continue to impair effectiveness. This study found that about 40% of post-2016 EIAs still lack long-term flood resilience measures [1,39]. While GIS technologies and predictive modelling represent significant advancements, their uneven implementation and lack of enforcement mechanisms highlight the need for ongoing improvement in the EIA processes [45,53,55,89,90,91]. This indicates that both opportunities and challenges are still arising from the evolution of EIA methodologies [6,84]. Future improvements should focus on strengthening the policy links between EIA processes and more comprehensive disaster risk reduction frameworks, requiring advanced hydrological assessments, simulation of different climate and land-use scenarios, and implementation of real-time monitoring systems through satellite data. These actions are essential for changing EIAs from reactive permitting tools to proactive tools for disaster risk reduction and climate-resilient development, especially in fragile ecosystems such as flood-prone areas.

While developed countries such as the USA, China, and the UK are leading in adopting these innovations to make the EIA processes more effective, developing countries, particularly in Africa and South Asia, are still behind in terms of their implementation. This study found that, for developing regions (Figure 6), the EIA technological advancements are still a challenge, leaving the vulnerable areas at a disadvantage in the management of flood risk [50,92,93,94,95,96]. The disconnect between policy frameworks and on-the-ground implementation of the EIA signifies one of the most significant barriers to effective floodplain and wetland conservation.

4.3. Flood Risk Creation Through Inadequate Integration of Hydrological Assessments in EIAs

The preservation of wetlands and floodplains has appeared as a critical component of effective flood risk management, with a global trend of wetland degradation, with approximately 64% of these vital ecosystems becoming lost since 1900 [1,3,60]. In South Africa, the situation appears particularly terrible, indicating 48% of the nation’s wetland ecosystems are classified as critically endangered, and only 11% of them receive adequate protection [1,23,60,97]. Prioritising short-term development above long-term resilience is a global concern revealed by the divergence between policy and practice [23,57,98]. This disparity makes it more difficult for EIAs to predict risks, particularly if floods increase in frequency due to climate change [53,99,100].

According to the literature, the floods are linked to climate change; wetland loss; destruction, degradation, or reduction of natural floodplains; the use of floodplain areas; and poor EIA enforcement, which illustrates how hydrological neglect leads to disasters [42,99,101,102,103]. Yet approximately 40% of post-2016 EIAs still omit climate adaptation strategies. To address this, this scoping review study urges mandatory HIAs for flood-prone developments, firmer policy enforcement, and advanced tools like MODFLOW, GIS, Hydrological Modelling Systems, and real-time monitoring. Without these reforms, EIAs will fail vulnerable communities, exposing them to escalating flood risks.

Moving forward, the findings of the study point to three key strategies essential for improving flood-prone area conservation and disaster risk management. The first strategy is that flood-prone specific EIAs should be mandatory for all developments happening in floodplains and wetlands, incorporating advanced hydrological modelling and climate change projections. The second strategy is policy enforcement, which must be strengthened through regular monitoring and meaningful penalties for non-compliance. Lastly, the community-centred approaches that combine traditional knowledge with scientific assessment methods can assist in bridging the gap between conservation goals and local development needs.

The integration of these strategies proposes a pathway to transform flood risk management from a reactive crisis disaster reaction to a proactive resilience-building approach. Policymakers can address ecosystem protection and community safety by prioritising wetland conservation as a natural flood buffer and coordinating EIA procedures with climate adaptation requirements. The lessons learned from the frequent flood disasters are a clear reminder that vulnerable populations will continue to suffer from more severe flood catastrophe events unless immediate action is taken to safeguard remaining wetlands and enhance floodplain management. This study emphasises how urgently coordinated efforts are needed to translate research findings into practical conservation measures and policy reforms.

4.4. Methodological Limitations of This Study

This scoping review is subject to methodological limitations, such as the search strategy, which was restricted to English-language publications within major indexed databases. This may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies published in other languages or in regional journals, hence potentially introducing language and publication bias. Furthermore, consistent with the objectives of a scoping review, the study aimed to map the scope of available literature rather than appraise the quality of individual studies; consequently, no formal quality assessment or risk-of-bias analysis was conducted. As a result, the synthesis describes broad trends and gaps but does not weigh findings according to methodological rigour. Finally, although software tools facilitated thematic and bibliometric analysis, the interpretation of keyword clusters and co-authorship networks remains inherently subject to a degree of researcher subjectivity.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to systematically evaluate EIA effectiveness through three key objectives: (1) evaluating the EIA technical approaches or methods used in flood-prone areas, (2) investigating the integration of hydrological assessments, and (3) analysing the evolution of EIA practices in relation to policy frameworks. This scoping review systematically addressed its three objectives to evaluate EIA effectiveness in flood-prone areas by providing robust insights into methodological, hydrological, and policy dimensions. The first objective was to assess EIA methodologies, which was achieved through a comprehensive analysis of 147 studies that identified a shift from qualitative methods like checklists (43% in 2005–2015) to quantitative tools like GIS and hydrological modelling (32% and 24% post-2016, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). However, 72% of EIAs still relied on outdated approaches. The second objective was to determine hydrological integration in EIA. This objective was also met by quantifying that only 28% of EIA studies incorporated HIA, with a mere 12% of South African floodplain EIAs using flood modelling (Figure 10). The third objective was to analyse methodological and policy evolution, which was fulfilled by linking tool advancements to policy frameworks like NEMA, discovering that 40% of post-2016 EIAs lacked climate adaptation strategies, revealing enforcement gaps. While these findings confirm the study’s success in addressing its objectives, limitations in case-specific depth and practical implementation insights highlight areas for future research. To enhance EIA efficacy, the study recommends mandating HIAs, adopting advanced tools like MODFLOW and GISs, and strengthening policy enforcement through stricter compliance monitoring.

This scoping assessment systematically highlights significant gaps in the effectiveness of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) in flood-prone areas, especially in countries where fast urbanisation and climate change increase flood risks. Even with a strong legislative framework such as NEMA, EIAs frequently fall short in incorporating advanced hydrological assessments; instead, they rely more on outdated methodologies and suffer in enforcing compliance and aligning with long-term climate change resilience strategies, especially in developing countries that are high-risk flood zones. According to the scoping review analysis, about 72% of EIAs lacked specialised hydrological assessment studies and relied more on fundamental checklists, limiting predictive accuracy for flood risk rather than predictive techniques like GIS, remote sensing, or flood modelling. Developed countries lead in methodological advancements, while flood-vulnerable countries like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia lag due to budgetary and technical limitations.

To enhance the effectiveness of the EIA in flood-prone areas and address these shortcomings, this study recommends mandating hydrological impact assessments (HIAs) in flood-prone developments; adopting advanced risk assessment tools/processes such as MODFLOW, GISs, remote sensing technology, and flood modelling; and strengthening policy enforcement through stricter compliance enforcement monitoring to improve risk assessment accuracy.

Additionally, capacity-building initiatives for EIA practitioners in developing countries to improve the adoption of advanced methodologies and international research partnerships are essential to bridge knowledge gaps in flood risk management and ensure equitable implementation. Without these improvements, EIAs will keep falling short in mitigating flood disasters, leaving vulnerable communities at risk of continuous floods. Thus, this study emphasises the urgent need for EIAs to evolve from current tools into proactive climate and disaster resilience instruments via the integration of scientific advancements such as hydrological modelling, enforcing robust regulations by closing policy implementation gaps, and prioritising long-term sustainability over short-term development gains. Future research should explore digital innovations such as real-time satellite monitoring, case-specific EIA effectiveness in high-risk flood zones, and equitable policy implementation strategies to further refine flood risk management strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18020768/s1, PRISMA Checklist. Reference [24] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.N.N., D.K., P.T.Z.S.-R. and P.M.; analysis, P.N.N., D.K., P.T.Z.S.-R. and N.B.; validation, P.N.N., D.K. and P.T.Z.S.-R.; formal analysis, P.N.N., D.K. and N.B.; investigation, P.N.N., D.K., P.T.Z.S.-R. and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.N.; writing—review and editing, D.K., P.T.Z.S.-R. and N.B.; visualisation, P.N.N. and N.B.; supervision, D.K., P.T.Z.S.-R. and P.M.; project administration, P.T.Z.S.-R.; funding acquisition, P.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Cape Town Staff Tuition Bursary.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Staff Tuition Bursary and the Department of Environmental and Geographical Science at the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adeeyo, A.O.; Ndlovu, S.S.; Ngwagwe, L.M.; Mudau, M.; Alabi, M.A.; Edokpayi, J.N. Wetland Resources in South Africa: Threats and Metadata Study. Resources 2022, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, I.; Alam, K.; Maghenda, M.; McDonnell, Y.; McLean, L.; Campbell, J. Unjust waters: Climate change, flooding and the urban poor in Africa. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S.; Almuktar, S.; Scholz, M. Impact of climate change on wetland ecosystems: A critical review of experimental wetlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramiaramanana, F.N.; Teller, J. Urbanization and Floods in Sub-Saharan Africa: Spatiotemporal Study and Analysis of Vulnerability Factors—Case of Antananarivo Agglomeration (Madagascar). Water 2021, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, E.-S.A.; Zahran, A.A.; Cashmore, M. Benchmarking performance: Environmental impact statements in Egypt. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl-Haider, U. EIA Effectiveness in Sensitive Alpine Areas: A Comparison of Winter Tourism Infrastructure Development in Germany and Austria. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Mo, H.; Zhan, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H. How does the environmental impact assessment (EIA) process affect environmental performance? Unveiling EIA effectiveness in China: A practical application within the thermal power industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaegen, M.; Muro, E. Contribution of a European spatial data infrastructure to the effectiveness of EIA and SEA studies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.S.; Fischer, T.B.; Shengji, L. Evaluating environmental impact assessment (EIA) in the countries along the belt and road initiatives: System effectiveness and the compatibility with the Chinese EIA. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapuarachchi, A.B.; Hughey, K.; Rennie, H. Effectiveness of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in addressing development-induced disasters: A comparison of the EIA processes of Sri Lanka and New Zealand. Nat. Hazards 2015, 81, 423–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinma, K.; Põder, T. Effectiveness of Environmental Impact Assessment system in Estonia. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Czachs, C.; Formayer, H.; Wachter, T.F.; Margelik, E.; Leitner, M.; Fischer, T.B. Climate change adaptation and EIA in Austria and Germany–Current consideration and potential future entry points. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 71, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, I.; Tsiolaki, F.; Stylianou, M.; Voukkali, I.; Sourkouni, G.; Argirusis, N.; Argirusis, C.; Zorpas, A.A. Evaluation of the effectiveness and performance of environmental impact assessment studies in Greece. Comptes Rendus. Chim. 2024, 26, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retief, F.; Welman, C.N.J.; Sandham, L. Performance of environmental impact assessment (EIA) screening in South Africa: A comparative analysis between the 1997 and 2006 EIA regimes. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2011, 93, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.; Cilliers, D.P.; Retief, F.P.; Alberts, R.C.; Bond, A.J. Regulators’ perceptions of environmental impact assessment (EIA) benefits in a sustainable development context. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyal, S.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Bhardwaj, S.K. A review on methodologies adopted during environmental impact assessment of development projects. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 2108–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubanga, R.O.; Kwarteng, K. A comparative evaluation of the environmental impact assessment legislation of South Africa and Zambia. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 83, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvijáková, L.; Zeleňáková, M.; Purcz, P. Evaluation of environmental impact assessment effectiveness in Slovakia. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabera, T.; Mutavu, G. Evaluation of the effectiveness of environmental impact assessment in East Africa: The case of Rwanda. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2022, 32, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, F.; Jha-Thakur, U.; Fischer, T.B. Enhancing EIA systems in developing countries: A focus on capacity development in the case of Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.R.; Mondal, S.; Kole, D. Environmental Impact Assessment: A Case Study on East Kolkata Wetlands. In Wastewater Management Through Aquaculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, T.K.; Sajjad, H.; Roshani; Rahaman, M.H.; Sharma, Y. Exploring the impact of land use/land cover changes on the dynamics of Deepor wetland (a Ramsar site) in Assam, India using geospatial techniques and machine learning models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 4043–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byaruhanga, N.; Kibirige, D.; Gokool, S.; Mkhonta, G. Evolution of Flood Prediction and Forecasting Models for Flood Early Warning Systems: A Scoping Review. Water 2024, 16, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, E. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA); A useful tool to address climate change in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy 2013, 1, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Kamau, J.W.; Mwaura, F. Climate change adaptation and EIA studies in Kenya. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2013, 5, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Hacking, T. Gaps in EIA incorporating climate change. In Proceedings of the IAIA12 Conference Proceedings’ Energy Future The Role of Impact Assessment 32nd Annual Meeting of the International Association for Impact Assessment, Porto, Portugal, 27 May–1 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Sayahnia, R.; Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Azadi, H. Integrating resilience assessment in environmental impact assessment. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2018, 14, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenning, R.J.; Apitz, S.E.; Kapustka, L.; Seager, T. The need for resilience in environmental impact assessment. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 969–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajman, N.N.; Zainun, N.Y.; Sulaiman, N.; Khahro, S.H.; Ghazali, F.E.M.; Ahmad, M.H. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Using Geographical Information System (GIS): An Integrated Land Suitability Analysis of Filling Stations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, M. Applications of geographic information systems, spatial analysis, and remote sensing in environmental impact assessment. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Impact Assessment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Wen, X.; Cao, X.; Yuan, H. A GIS and hybrid simulation aided environmental impact assessment of city-scale demolition waste management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, H.; Subramani, S.E.; Partheeban, P.; Sridhar, M. IoT-and GIS-based environmental impact assessment of construction and demolition waste dump yards. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, M.; Sowman, M.; Day, K. South Africa’s EIA Screening Tool: A preliminary study of how users perceive its accuracy and utility. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2023, 41, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, M.A.; Salah, W. Secondary data-associated challenges for environmental assessment in developing countries; case of Egypt. MSA Eng. J. 2023, 2, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.J.; Dziedzic, M. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness: A state of the art. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 68, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Gonzalez, A.L.; Toro, J.; Zamorano, M. Effectiveness of environmental impact statement methods: A Colombian case study. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harelimana, V.; Gao, Z.J.; Nyiranteziryayo, E.; Nwankwegu, A.S. Identification of weaknesses in the implementation of environmental impact assessment regulations in industrial sector: A case study of some industries in Rwanda, Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, N.; Wood, C. Public participation in environmental impact assessment—Implementing the Aarhus Convention. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, R.C.; Retief, F.P.; Cilliers, D.P.; Roos, C.; Hauptfleisch, M. Environmental impact assessment (EIA) effectiveness in protected areas. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Tu, T.; Nitivattananon, V. Adaptation to flood risks in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2011, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronez, F.A.; Montaño, M. Comprehensive framework for analysis of EIA effectiveness: Evidence from Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 108, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.; Requena, I.; Zamorano, M. Environmental impact assessment in Colombia: Critical analysis and proposals for improvement. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.D.; Vu, C.C. EIA effectiveness in Vietnam: Key stakeholder perceptions. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Hilton, B. A Spatially Intelligent Public Participation System for the Environmental Impact Assessment Process. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2013, 2, 480–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Takezawa, M.; Gotoh, H. Environmental impact assessment in the Apure River. In Proceedings of the River Basin Management IV, Kos, Greece, 8 May 2007; pp. 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Lara, J.A.; Batista, L.; Le Pira, M.; Arranz-López, A.; Arce-Ruiz, R.M.; Inturri, G.; Pinho, P. Revealing EIA process-related barriers in transport projects: The cases of Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 83, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruopienė, J.; Židonienė, S.; Dvarionienė, J. Current practice and shortcomings of EIA in Lithuania. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2009, 29, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanteep, K.; Murayama, T.; Nishikizawa, S. Environmental impact assessment system in Thailand and its comparison with those in China and Japan. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 58, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayso, E.; Köz, İ.; Doğanalp, S.; Aslan, M.; Tuşat, E.; Kahveci, M.; Taşpınar, C. Assessing the impact of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş and Hatay earthquakes on cadastre and property data using GPS and GIS. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 23, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherqui, F.; Belmeziti, A.; Granger, D.; Sourdril, A.; Le Gauffre, P. Assessing urban potential flooding risk and identifying effective risk-reduction measures. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 514, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbuena, R., Jr.; Kawamura, A.; Medina, R.; Amaguchi, H.; Nakagawa, N.; Bui, D.D. Environmental impact assessment of structural flood mitigation measures by a rapid impact assessment matrix (RIAM) technique: A case study in Metro Manila, Philippines. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 456-457, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddlesden, D.; Singleton, A.D.; Fischer, T.B. A Survey of the Use of Geographic Information Systems in English Local Authority Impact Assessments. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2012, 14, 1250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ackere, S.; Beullens, J.; Vanneuville, W.; De Wulf, A.; De Maeyer, P. FLIAT, An Object-Relational GIS Tool for Flood Impact Assessment in Flanders, Belgium. Water 2019, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douven, W.; Buurman, J. Planning practice in support of economically and environmentally sustainable roads in floodplains: The case of the Mekong delta floodplains. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S.K.; Plater, A.J. Records of pan (floodplain wetland) sedimentation as an approach for post-hoc investigation of the hydrological impacts of dam impoundment: The Pongolo river, KwaZulu-Natal. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4226–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.N.; Zwain, H.M.; Nile, B.K. Modeling the effects of land-use and climate change on the performance of stormwater sewer system using SWMM simulation: Case study. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šoltész, A.; Zeleňáková, M.; Čubanová, L.; Šugareková, M.; Abd-Elhamid, H. Environmental Impact Assessment and Hydraulic Modelling of Different Flood Protection Measures. Water 2021, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Mo, S.; Wu, H.; Qu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L. Influence of human activities and climate change on wetland landscape pattern-A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.S.; Lee, D.K.; Choi, J. Evaluating the effectiveness of mitigation measures in environmental impact assessments: A comprehensive review of development projects in Korea. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhateria, R. EIA Procedure—Mitigation and Impact Management. In Environmental Impact Assessment: A Journey to Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kanellos, C.A.; Riviere, M.; Brunelle, T.; Shanafelt, D.W. Accounting for land-use changes in environmental impact assessments of wood products: A review. Forests 2024, 15, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Nair, S.S.; Dhyani, S. Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in EIA/SEA for Climate and Disaster Resilient Development. In Disaster Risk and Management Under Climate Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 437–455. [Google Scholar]

- Retief, F.P.; Alberts, R.C.; Cilliers, D.; Roos, C.; Moolman, J.; Bond, A. Unique features of environmental impact assessment (EIA) in protected areas (PAs)–towards best practice principles. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2025, 43, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandham, L.A.; van Heerden, A.J.; Jones, C.E.; Retief, F.P.; Morrison-Saunders, A.N. Does enhanced regulation improve EIA report quality? Lessons from South Africa. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, H.; Devi, H.S.; Borah, S.B.; Das, A.K. Land cover dynamics and their driving factors in a protected floodplain ecosystem. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.; Casasanta Mostaço, F.; Jaeger, J.A. Lack of consideration of ecological connectivity in Canadian environmental impact assessment: Current practice and need for improvement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2022, 40, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Modibbo, U.M.; Jafari Kolashlou, H.; Ali, I.; Kavousi, N. Environmental impact assessment with rapid impact assessment matrix method: During disaster conditions. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2024, 10, 1344158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogato, G.S.; Bantider, A.; Geneletti, D. Dynamics of land use and land cover changes in Huluka watershed of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.B.; de Oliveira Vasconcelos, A.; Mamede da Silva, P.; Carrascal, M.H.; La Rovere, E.L.; de Almeida, J.R.; Landau, L. GIS-based modeling of the environmental vulnerability of the Amazon region to the upstream oil and gas activities. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2024, 42, 522–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashmore, M.; Bond, A.; Sadler, B. Introduction: The effectiveness of impact assessment instruments. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D.; Biasiolli, A.; Morrison-Saunders, A. Land take and the effectiveness of project screening in Environmental Impact Assessment: Findings from an empirical study. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 67, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jongh, P. Uncertainty in EIA. In Environmental Impact Assessment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Ge, W.; Qian, H.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, Y. Impact of floods on the environment: A review of indicators, influencing factors, and evaluation methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha-Thakur, U.; Fischer, T.B. 25years of the UK EIA System: Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 61, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Geißler, G.; Montaño, M. Addressing climate change in Berlin’s local land-use plans through strategic environmental assessment and knowledge brokering. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayembe, R.; Simpson, N.P.; Rumble, O.; Norton, M. Integrating climate change in Environmental Impact Assessment: A review of requirements across 19 EIA regimes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, A.R.A.; Fidélis, T. Integrating climate change into environmental impact assessments of dams: Insights from three case studies using an analytical model. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2025, 43, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.R.B.d.A. Incorporating Climate Change Risks in the Environmental Impact Assessment of Dams. PhD Thesis, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal Adegboyega, M.; Vincent-Akpu, I.; Suleiman, A.O. Mainstreaming Climate Change into EIA Process in Nigeria: Perspectives from Projects in Northern Nigeria. Acad. J. INC. 2024, 3, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvihill, P.R. Pieces of an Inter-Disciplinary Puzzle: Connecting Environmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Disaster Studies. Geogr. Compass 2024, 18, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.J.; de Oliveira, C.M.R.; Dziedzic, M. Environmental federalism in EIA policy: A comparative case study of Paraná, Brazil and California, US. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 122, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashmore, M.; Gwilliam, R.; Morgan, R.; Cobb, D.; Bond, A. The interminable issue of effectiveness: Substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2004, 22, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.; Cilliers, D.; Retief, F.; Alberts, R.; Roos, C.; Moolman, J. Using an artificial intelligence chatbot to critically review the scientific literature on the use of artificial intelligence in environmental impact assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2024, 42, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega, L.; Gbolahan, B.T.; Vincent-Akpu, I.; Woke, G.N. Enhancing Environmental Impact Assessments through AI-Driven App: App Review of the EIA Report for Proposed Erection of High Communication Towers in Obajana, Kogi State, Nigeria. J. Pollut. Monit. Eval. Stud. Control 2024, 3, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ngcobo, S. Using AI to Enhance EIA Decision Making Processes: A South African Perspective. In Proceedings of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Kruger National Park (Skukuza), South Africa, 8–13 October 2024; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Pagán, L.A.; Gao, Q.; Yu, M. Analysis of the evolution of environmental laws in Puerto Rico (1897–2021): A new classification system, trends, and political influences. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Gonzalez, A.L.; Nita, A.; Toro, J.; Zamorano, M. From procedural to transformative: A review of the evolution of effectiveness in EIA. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, L. Institutional Mechanisms for Environmental Monitoring: Ecological Expertise and Environmental Impact Assessment. In Proceedings of the Balkan and Near Eastern Congress Series on Economics, Business and Management, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 16–17 March 2024; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bhanwala, V.; Krishnan, S. Enhancing Disaster Resilience Through The Integration of Disaster Risk Reduction and Response In Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Policy. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, Washington, DC, USA, 9–13 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Wu, M.; Wu, S.-N.; Sui, X.; Wen, J.-Y.; Wang, P.-Y.; Cheng, L.; Lanza, G.R.; Liu, C.-N.; Jia, W.-L. Bridging gaps between environmental flows theory and practices in China. Water Sci. Eng. 2019, 12, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. The evolution of China’s environmental impact assessment system: Retrospect and prospect from the perspective of effectiveness evaluation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreebha, S.; Padmalal, D. Environmental impact assessment of sand mining from the small catchment rivers in the southwestern coast of India: A case study. Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; English, A.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.D. Improving the effectiveness of planning EIA (PEIA) in China: Integrating planning and assessment during the preparation of Shenzhen’s Master Urban Plan. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ouyang, H. Evaluating EIA implementation in China: An empirical study of 161 EIA judicial cases. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Bhattacharya, S. User guide of Google Earth Engine based Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) Tool. EarthArXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Basu, A.; Bharat, G.K.; Chakraborty, P.; Sarkar, S.K. Adaptive co-management model for the East Kolkata wetlands: A sustainable solution to manage the rapid ecological transformation of a peri-urban landscape. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, J.; Steinbach, P. From flood risk to indirect flood impact: Evaluation of street network performance for effective management, response and repair. In Proceedings of the Flood Recovery, Innovation and Response I, London, UK, 2–3 July 2008; pp. 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, Y.S.; Mat Desa, S.; Md. Noh, M.N.; Tan, M.L.; Zakaria, N.A.; Chang, C.K. Assessing the Effectiveness of Mitigation Strategies for Flood Risk Reduction in the Segamat River Basin, Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Montanari, A.; Lins, H.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Brandimarte, L.; Blöschl, G. Flood fatalities in Africa: From diagnosis to mitigation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L. Impacts of Regional Groundwater Flow and River Fluctuation on Floodplain Wetlands in the Middle Reach of the Yellow River. Water 2020, 12, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, T.; Quevauviller, P.; Eisenreich, S.J.; Vaes, G. Impacts of climate and land use changes on flood risk management for the Schijn River, Belgium. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 89, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.