1. Introduction

The confluence of accelerating environmental degradation and pervasive digital transformation has positioned university students at a critical juncture where their capacity to engage meaningfully with environmental challenges increasingly depends on digital competencies. As future decision-makers and change agents, students must navigate an information landscape characterized by both unprecedented access to environmental data and persistent challenges in evaluating its credibility and relevance. Contemporary scholarship reveals a paradox in student engagement with environmental information: while digital platforms provide extensive access to environmental content and facilitate advocacy efforts [

1,

2], more than 40% of students demonstrate significant deficiencies in critically assessing online information’s reliability, particularly regarding commercial bias and source credibility [

3,

4]. Although students can readily locate environmental information, their evaluative processes often remain superficial, lacking the reasoned justification necessary for informed environmental decision-making [

5]. Evidence suggests that targeted interventions, including digital games and specialized eco-learning platforms, can enhance both digital literacy and environmental knowledge [

6,

7], yet the translation of digital competencies into environmental action remains mediated by metacognitive strategies and self-regulation capacities that vary substantially across student populations [

8].

This translation challenge is further complicated by a persistent attitude–behavior gap in student environmental engagement. Despite 85–91% of university students worldwide reporting positive attitudes toward environmental protection and expressing willingness to make personal sacrifices for environmental causes [

9,

10], actual pro-environmental behaviors reveal marked inconsistency. Only 60% of students regularly practice waste separation, and merely 20% consistently engage in other sustainable actions such as reducing energy consumption or avoiding single-use items [

10,

11,

12]. This discrepancy stems from a complex interplay of external barriers, including cost and convenience constraints, and internal factors such as limited self-efficacy and entrenched habitual patterns [

10,

11]. Research identifies moral obligation and participation in environmental education as critical predictors of sustainable behavior [

13,

14], suggesting that cognitive awareness alone proves insufficient to motivate behavioral change without accompanying emotional and ethical engagement.

Emerging evidence indicates that digital literacy positively correlates with environmental responsibility among university students, though the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain inadequately theorized. Students with advanced digital competencies demonstrate heightened awareness of technology’s environmental impact and exhibit stronger inclinations toward environmentally responsible behaviors, including energy conservation and responsible electronic waste management [

7,

15,

16]. While quantitative studies confirm statistically significant positive correlations between digital literacy and environmental responsibility [

1,

17], the strength and directness of these relationships vary considerably across contexts and are moderated by factors including curriculum design, integration of sustainability content into digital education, and students’ intrinsic motivation [

7,

8,

15]. Furthermore, digital literacy supports the development of ethical and responsible attitudes foundational to environmental stewardship [

17,

18], suggesting that the relationship between digital competencies and environmental action operates through attitudinal and value-based pathways that warrant systematic investigation.

Historical empathy—defined as a multidimensional psychological construct encompassing cognitive and affective capacities to comprehend past decisions and their consequences [

19,

20]—may represent a crucial but overlooked mediating mechanism in this relationship. This construct integrates contextualization of historical actions within temporal and environmental frameworks, recognition of historical actors’ values and beliefs, affective engagement with past individuals, and informed imagination to interpret incomplete historical evidence [

20,

21,

22]. When students employ digital tools to explore historical environmental failures and successes, they may develop empathy not only for those affected by past decisions but also for future generations who will inherit contemporary choices [

6,

23]. This empathetic engagement is associated with moral responsibility and deeper connection to environmental outcomes, rendering historical lessons personally relevant and emotionally resonant [

23,

24]. Consequently, historical empathy may function as a transformative bridge that converts digital knowledge into internalized values and attitudes, thereby motivating students to adopt environmentally responsible behaviors [

16,

23,

24]. Digital literacy is associated with access to, interpretation of, and engagement with diverse environmental histories through digital archives, simulations, and interactive media [

16,

25,

26,

27], yet whether and how this access relates to historical empathy that subsequently shapes environmental responsibility remains empirically untested.

Historical empathy is conceptualized in this study as a hybrid cognitive-affective ethical competence that uniquely integrates contextualized historical reasoning with morally charged emotional engagement [

20,

28]. This construct is selected as the mediator because it is discipline-specific to historical learning and theorized to bridge historical understanding with present-oriented citizenship, inclusion, and moral concern [

19,

28]. Unlike more general predictors such as moral obligation [

29], environmental identity [

30], or self-efficacy [

31], historical empathy synthesizes evidence-based contextualization with ethical judgment and caring responses [

20], making it a theoretically proximal mechanism through which historically framed environmental narratives can shape contemporary ethical commitments [

19,

28]. This positioning aligns with conceptualizations of empathy as inherently relational and morally situated [

32], while maintaining its distinctive cognitive-contextual foundation in historical inquiry.

Despite growing scholarly interest in both digital literacy and environmental sustainability, a critical research gap persists regarding the intersection of these domains with historical consciousness. Existing literature predominantly examines digital competencies and environmental awareness as discrete constructs, with few studies integrating digital literacy, environmental responsibility, and historical empathy within a unified theoretical framework [

17,

23,

33,

34]. While digital tools have demonstrated potential for fostering environmental awareness through immersive technologies [

35,

36], the integration of historical consciousness within these interventions remains largely underexplored [

37]. Research on digitalization and sustainability in higher education focuses primarily on competency development while seldom incorporating historical or cultural perspectives [

34,

38]. Most critically, no prior studies have empirically tested historical empathy as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between digital literacy and environmental responsibility. Although theoretical arguments suggest that digital tools enable access to historical environmental narratives that may foster empathy [

16,

25,

26,

27], and separate research indicates that historical empathy influences ethical decision-making [

23,

24], these relationships have never been integrated into a testable mediation model.

The fundamental problem is that the psychological mechanisms through which digital literacy influences environmental responsibility among university students remain poorly understood. While research confirms positive correlations between digital competencies and environmental behaviors [

7,

15,

16,

17], the mediating pathways explaining this relationship remain theoretically underdeveloped and empirically untested. Theoretically, digital literacy enables access to historical environmental narratives, historical empathy transforms this information into emotionally resonant moral commitments through cognitive contextualization and affective engagement, and these commitments subsequently motivate pro-environmental behaviors—bridging the attitude–behavior gap by rendering abstract environmental concerns personally meaningful across temporal perspectives [

19,

20,

23,

24,

28]. Without understanding these processes, educators lack evidence-based guidance for designing interventions that effectively translate environmental knowledge into sustainable action, perpetuating the attitude–behavior gap in sustainability education.

The present study addresses this gap by investigating whether historical empathy mediates the relationship between digital literacy and environmental responsibility among university students. Specifically, this research examines: (1) the relationships between digital literacy and environmental responsibility, (2) the relationships between digital literacy and historical empathy dimensions (cognitive, affective, and behavioral), (3) the relationship between historical empathy and environmental responsibility, (4) whether historical empathy mediates the digital literacy–environmental responsibility relationship, and (5) the proportion of total effect accounted for by indirect versus direct pathways. Through mediation analysis, this study aims to elucidate the mechanisms through which digital competencies translate into environmentally responsible attitudes and behaviors, providing evidence-based guidance for curriculum development and pedagogical interventions designed to cultivate digitally literate, historically informed, and environmentally responsible graduates.

3. Results

Preliminary analyses examined demographic differences across the main sample (N = 927) to assess the representativeness and homogeneity of the participant groups. Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to explore potential associations between gender and other demographic variables, specifically grade level and residence. As presented in

Table 2, the analysis revealed no statistically significant relationship between gender and grade level, χ

2(3, N = 927) = 3.191,

p = 0.363, indicating that male and female students were evenly distributed across all four undergraduate years. Similarly, the relationship between gender and residence was not statistically significant, χ

2(1, N = 927) = 2.270,

p = 0.132, demonstrating comparable proportions of male and female students from both rural and urban backgrounds. These findings suggest that gender differences did not systematically vary with educational level or residential context, supporting the appropriateness of subsequent analyses without controlling for these demographic factors.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among the study variables. Pearson product–moment correlations revealed significant positive associations among all primary variables and their subscales. As shown in

Table 3, digital literacy demonstrated differential patterns of association with the three subscales of historical empathy, showing the strongest correlation with cognitive empathy (r = 0.337,

p < 0.001), followed by affective empathy (r = 0.324,

p < 0.001), with the weakest but still significant correlation observed with behavioral empathy (r = 0.209,

p < 0.001). Digital literacy also exhibited moderate to strong positive correlations with both historical empathy total score (r = 0.454,

p < 0.001) and environmental responsibility (r = 0.398,

p < 0.001). The intercorrelations among the historical empathy subscales ranged from r = 0.125 to r = 0.165 (

p < 0.001), indicating moderate independence among the three dimensions.

These findings suggest that digital competencies may be particularly relevant for cognitive dimensions of historical understanding—such as contextualizing past events and recognizing historical actors’ perspectives—while showing somewhat weaker associations with affective and behavioral components. Notably, cognitive empathy showed the strongest relationship with environmental responsibility (r = 0.178, p < 0.001) compared to affective empathy (r = 0.167, p < 0.001) and behavioral empathy (r = 0.156, p < 0.001), while historical empathy total score demonstrated a moderate correlation with environmental responsibility (r = 0.254, p < 0.001). These bivariate relationships provided initial support for investigating mediation effects, as recommended theoretical prerequisites were met: the predictor variable (digital literacy) correlated significantly with both the mediator (historical empathy) and the outcome variable (environmental responsibility), and the mediator correlated significantly with the outcome.

To test the central hypothesis that historical empathy mediates the relationship between digital literacy and environmental responsibility, a mediation analysis was conducted using Hayes’ PROCESS macro Model 4 with 5000 bootstrap samples. The theoretical model proposed that digital literacy would enhance students’ capacity to engage with historical environmental narratives through digital tools, thereby cultivating historical empathy that subsequently motivates environmental responsibility. This indirect pathway would operate alongside a direct effect of digital literacy on environmental responsibility, reflecting the multifaceted ways digital competencies shape sustainable attitudes and behaviors. The mediation framework thus conceptualized historical empathy as a transformative psychological mechanism that converts digital access to environmental histories into personally meaningful moral commitments toward environmental stewardship.

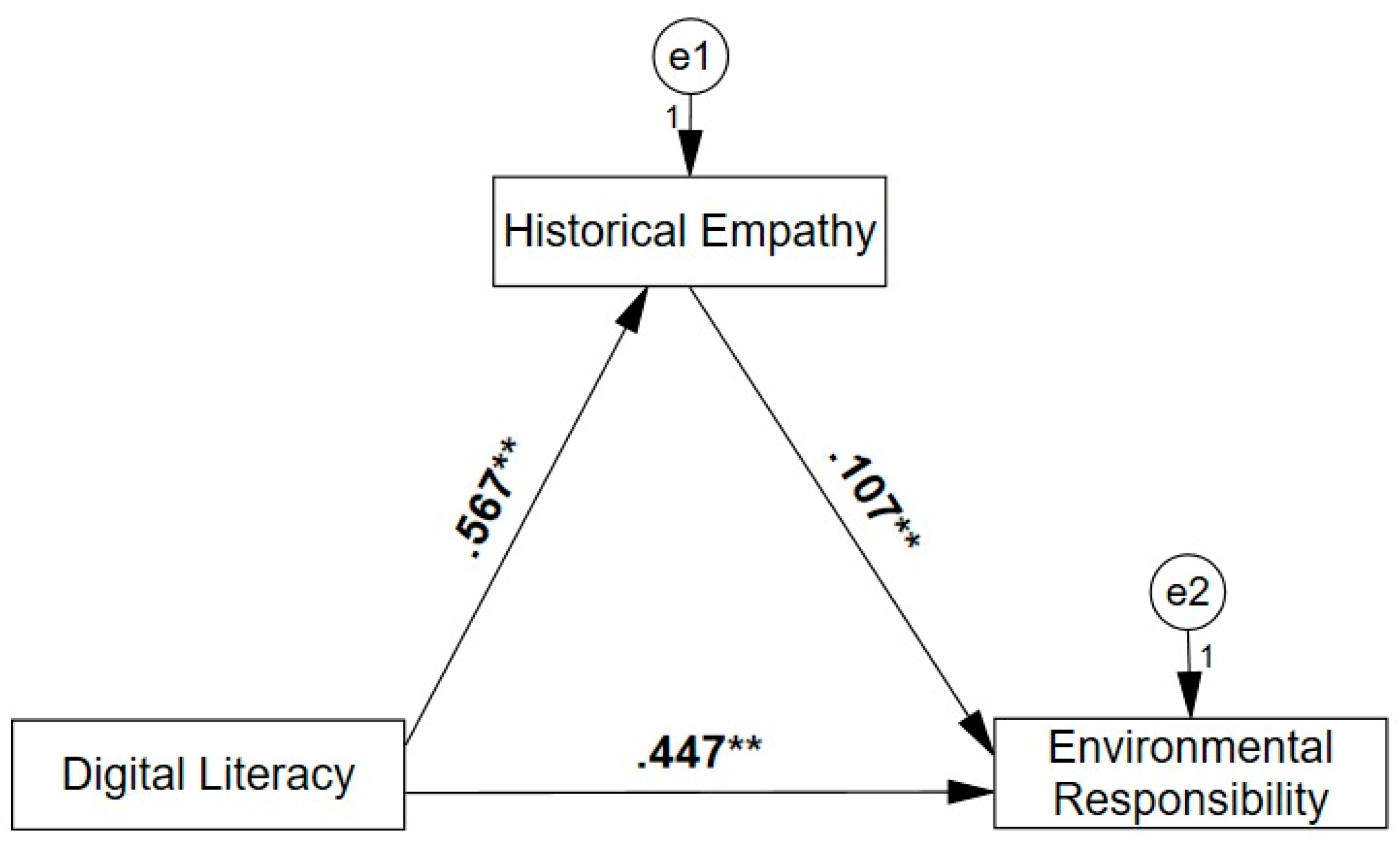

The statistical mediation model, illustrated in

Figure 1, examined both the direct association of digital literacy with environmental responsibility and the indirect association through historical empathy. As presented in

Table 4, the total association of digital literacy with environmental responsibility was statistically significant (c = 0.3174, SE = 0.0177, t = 17.94,

p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.2827, 0.3521]), indicating that higher levels of digital literacy were associated with greater environmental responsibility.

The decomposition of this total association into direct and indirect components revealed a significant statistical mediation pattern. The direct association of digital literacy with environmental responsibility, controlling for historical empathy, remained statistically significant (c’ = 0.2793, SE = 0.0214, t = 13.06,

p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.2373, 0.3213]), with a standardized coefficient of c’ = 0.4472. Simultaneously, digital literacy demonstrated a strong positive association with historical empathy (a = 0.4775, SE = 0.0228, t = 20.97,

p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.4328, 0.5222]), with a standardized coefficient of 0.5676, accounting for approximately 32.22% of the variance in historical empathy (R

2 = 0.3222). Historical empathy, in turn, was significantly associated with environmental responsibility (b = 0.0797, SE = 0.0254, t = 3.14,

p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.0298, 0.1296]), with a standardized coefficient of 0.1073. These path coefficients are summarized in

Table 5, which provides comprehensive statistical information for all regression pathways in the mediation model.

The indirect effect of digital literacy on environmental responsibility through historical empathy was statistically significant, as evidenced by the bootstrap confidence interval that did not include zero (indirect effect = 0.0381, SE = 0.0130, 95% CI [0.0132, 0.0636]). The completely standardized indirect effect was 0.0609 (95% CI [0.0200, 0.1054]), indicating that approximately 12.0% of the total effect of digital literacy on environmental responsibility was mediated through historical empathy. Correspondingly, the direct effect accounted for 88.0% of the total effect, suggesting partial mediation. These results indicate that while digital literacy exerts a substantial direct influence on environmental responsibility, a meaningful portion of this relationship operates indirectly through the enhancement of historical empathy. The model explained 26.60% of the variance in environmental responsibility (R2 = 0.2660, F(2, 924) = 167.40, p < 0.001), indicating that while the model explains moderate variance, additional mediating variables likely contribute to the digital literacy–environmental responsibility relationship.

The statistical mediation findings provide empirical support for an explanatory model in which historical empathy is associated with the relationship between digital competencies and environmental attitudes and behaviors. Students with stronger digital literacy skills appear better able to access, interpret, and emotionally engage with historical environmental narratives, which is associated with a sense of responsibility toward contemporary and future environmental challenges. Nevertheless, the predominance of the direct association suggests that digital literacy relates to environmental responsibility through multiple pathways beyond historical empathy, warranting further investigation of additional variables in future research.

4. Discussion

The statistical mediation analysis revealed that historical empathy partially accounts for the relationship between digital literacy and environmental responsibility among university students, explaining approximately 12% of the total association. This finding suggests that digital competencies are associated with environmental responsibility through dual pathways: a substantial direct relationship and a meaningful indirect pathway through historical consciousness. The strong correlation between digital literacy and cognitive empathy, compared to affective and behavioral dimensions, indicates that digital tools are primarily associated with students’ capacity to contextualize historical environmental decisions rather than emotional engagement. Although historical empathy accounts for a modest 12% of the total association, its unique contribution lies in temporally contextualizing environmental decisions—connecting past failures, present choices, and future consequences—a dimension not captured by traditional mediators such as moral norms or environmental concern, which typically explain 15–35% of variance individually.

The modest proportion of variance explained by historical empathy (12% of total effect) and the model overall (26.6% of variance in environmental responsibility) warrants careful interpretation. From a practical perspective, a 12% mediation effect represents a meaningful educational target: interventions integrating historical environmental narratives with digital tools could complement existing approaches that address direct pathways. The substantial unexplained variance (73.4%) suggests multiple mechanisms operate simultaneously. Likely contributors include self-efficacy beliefs regarding environmental action [

31], environmental identity and personal connection to nature [

30], moral norms and perceived behavioral control [

29], social norms and peer influence [

14], access to sustainable infrastructure, and socioeconomic factors affecting sustainable consumption choices [

10,

11].

These findings align with previous research establishing positive correlations between digital literacy and environmental responsibility. However, the current study extends understanding by identifying historical empathy as a statistical mediator previously overlooked in sustainability education literature. The results corroborate evidence that digital competencies are associated with environmentally responsible behaviors through access to environmental information and enhanced critical evaluation capacities [

7,

15]. However, our findings advance beyond prior work by demonstrating patterns consistent with a model in which digital tools relate to engagement with historical environmental narratives, which is associated with empathy that may motivate sustainable action [

23,

24]. The partial mediation observed supports the theoretical proposition that digital literacy operates through multiple pathways, consistent with research highlighting the importance of metacognitive strategies and ethical engagement in translating environmental knowledge into action [

8,

13].

These findings carry significant implications for curriculum development and pedagogical practice in higher education. Educators should integrate digital literacy instruction with historical environmental case studies, enabling students to explore past ecological failures and successes through digital archives, simulations, and interactive media. This approach may address the persistent attitude–behavior gap in student environmental engagement by fostering emotional and ethical connections that complement cognitive awareness. Universities should design interdisciplinary courses that deliberately cultivate historical empathy alongside digital competencies, positioning sustainability education within temporal contexts that illuminate contemporary choices’ consequences for future generations. Furthermore, institutions should develop digital learning environments that facilitate critical engagement with diverse environmental histories, thereby transforming abstract environmental concerns into personally relevant moral imperatives. Such pedagogical innovations may enhance students’ self-efficacy and moral obligation, identified as critical predictors of sustainable behavior.

These findings should be interpreted within the Egyptian cultural and educational context. Egyptian university students engage with environmental responsibility through frameworks influenced by Islamic environmental stewardship principles (khilafah, mizan) that emphasize intergenerational justice and resource trusteeship, which may amplify the relevance of historical consciousness in environmental decision-making. Additionally, Egypt’s unique environmental history—including millennia of Nile-dependent agriculture, ancient sustainability practices, and contemporary challenges such as desertification and water scarcity—provides regionally specific historical narratives that may differentially activate historical empathy compared to contexts with different environmental legacies. The mediation patterns observed here may reflect culturally specific ways of connecting past, present, and future environmental concerns that warrant empirical examination across diverse cultural settings before broader generalization.

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these findings. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, as the directionality of relationships among digital literacy, historical empathy, and environmental responsibility remains uncertain. While statistical mediation analysis can identify patterns consistent with theoretical models, it cannot establish that digital literacy causally influences historical empathy, which in turn causally affects environmental responsibility. The observed associations may reflect alternative causal structures, reverse causation, or reciprocal relationships that cannot be distinguished with cross-sectional data. Convenience sampling from a single Egyptian university limits generalizability across diverse cultural, educational, and socioeconomic contexts. Reliance on self-report measures introduces potential social desirability bias, particularly for environmental responsibility assessments where students may overreport sustainable attitudes and behaviors. The study did not account for potential confounding variables such as prior environmental education, socioeconomic status, or access to digital resources, which may influence observed relationships. Additionally, the mediation model explained moderate variance, suggesting unmeasured variables contribute substantially to environmental responsibility. The lack of behavioral observations limits conclusions about actual pro-environmental actions versus reported intentions.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to establish temporal precedence and examine how digital literacy and historical empathy develop concurrently to influence environmental responsibility over time. Experimental interventions testing pedagogical approaches that integrate digital tools with historical environmental education would provide causal evidence for the proposed mechanisms. Studies should investigate additional mediators and moderators, including self-efficacy, moral obligation, and critical thinking dispositions, to comprehensively map pathways linking digital competencies with sustainable behaviors.

Cross-cultural research across diverse geographical and institutional contexts would enhance generalizability and reveal cultural variations in these relationships. Future studies should specifically examine how Arabic dialect variations and regional cultural contexts influence the conceptualization and expression of environmental responsibility and historical empathy, as linguistic nuances and cultural values may moderate the observed mediation pathways. Comparative investigations across Arab-speaking countries with different dialects (e.g., Egyptian, Gulf, Levantine, Maghrebi) and varying educational systems—including public versus private institutions, traditional versus technology-enhanced learning environments, and nations with different emphases on environmental education in their national curricula—would illuminate whether these relationships operate similarly across diverse Arabic-speaking populations and reveal how systemic educational factors shape the development of digital competencies and environmental consciousness. Mixed-methods approaches incorporating behavioral observations, digital trace data, and qualitative interviews would address self-report limitations while capturing nuanced processes underlying environmental decision-making. Finally, research should examine domain-specific applications, exploring how particular digital tools and historical narratives differentially influence environmental attitudes and actions.