Characteristics and Kinetics of the Co-Pyrolysis of Oil Shale and Municipal Solid Waste Assessed via Thermogravimetric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Process

2.3. Kinetics Methods

3. Results and Discussion

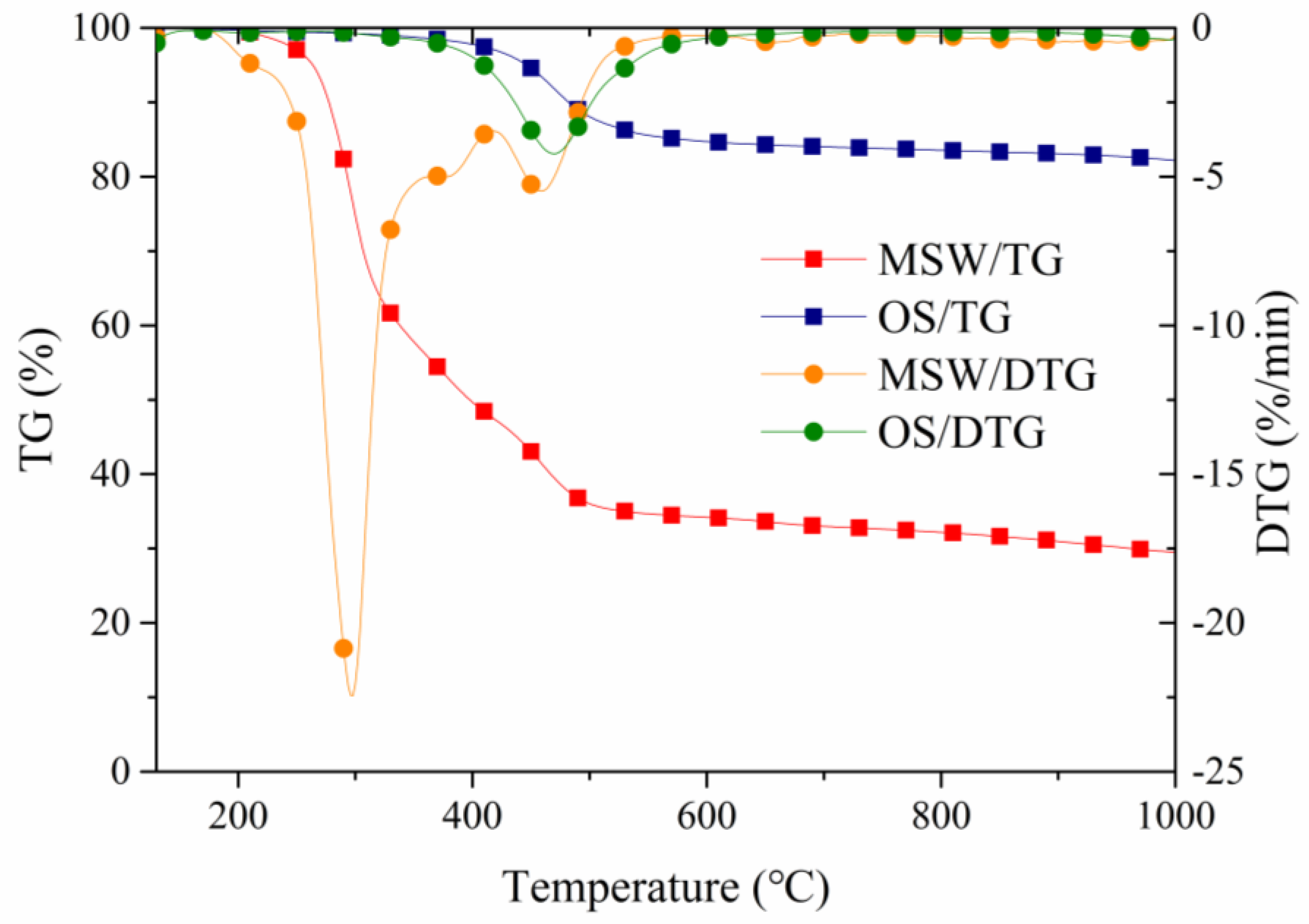

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Individual OS and MSW

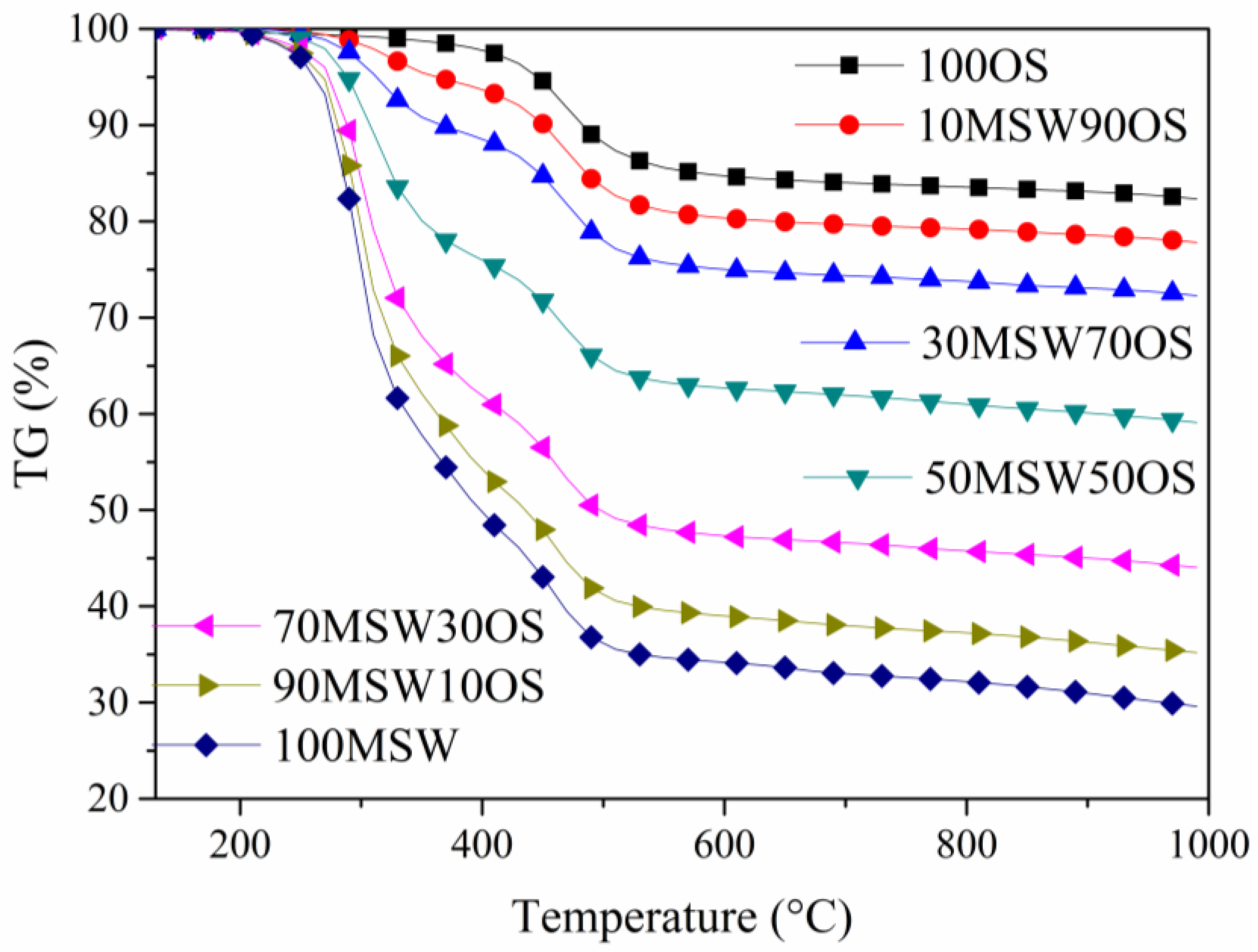

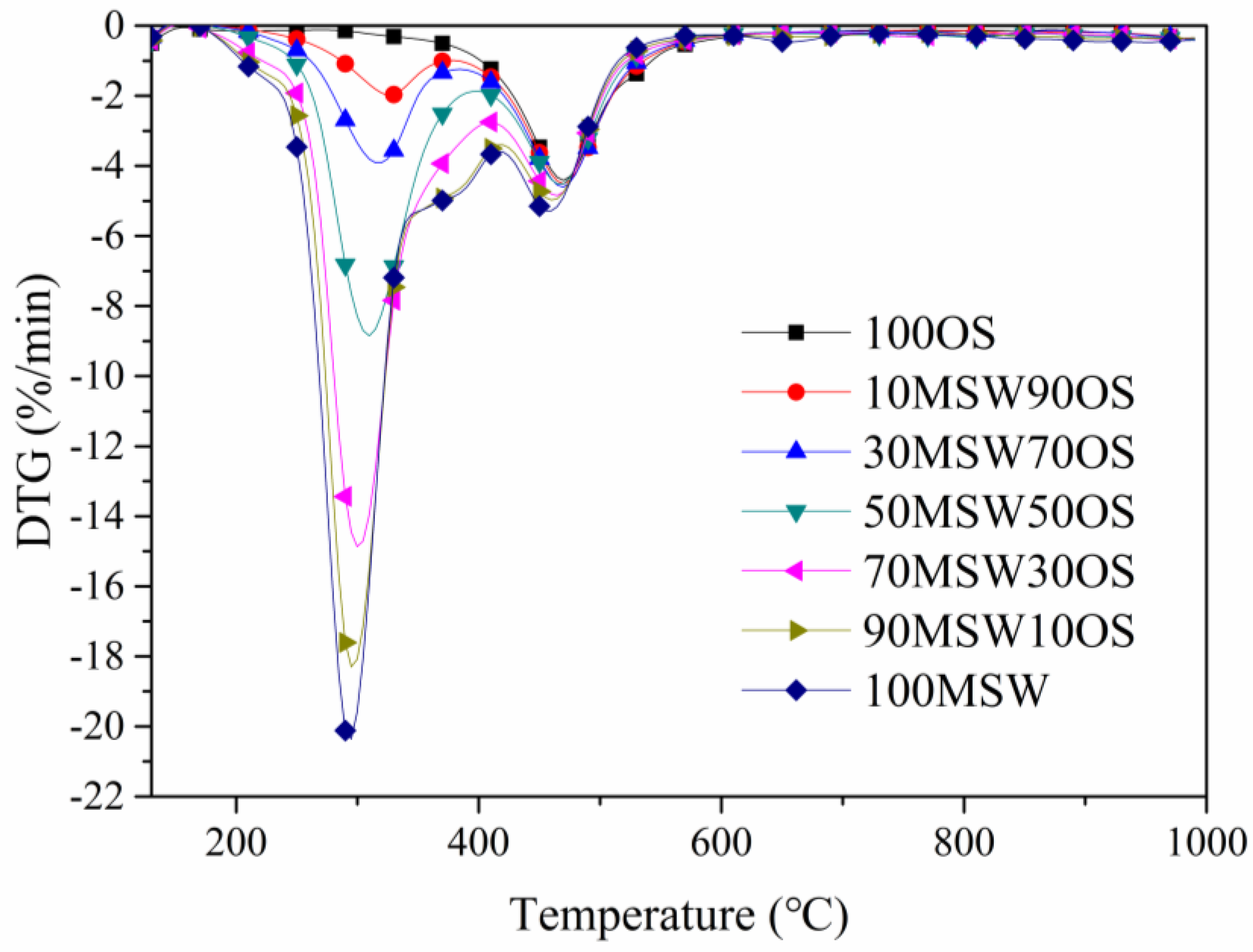

3.2. Co-Pyrolysis Analysis Under Different Blending Ratios

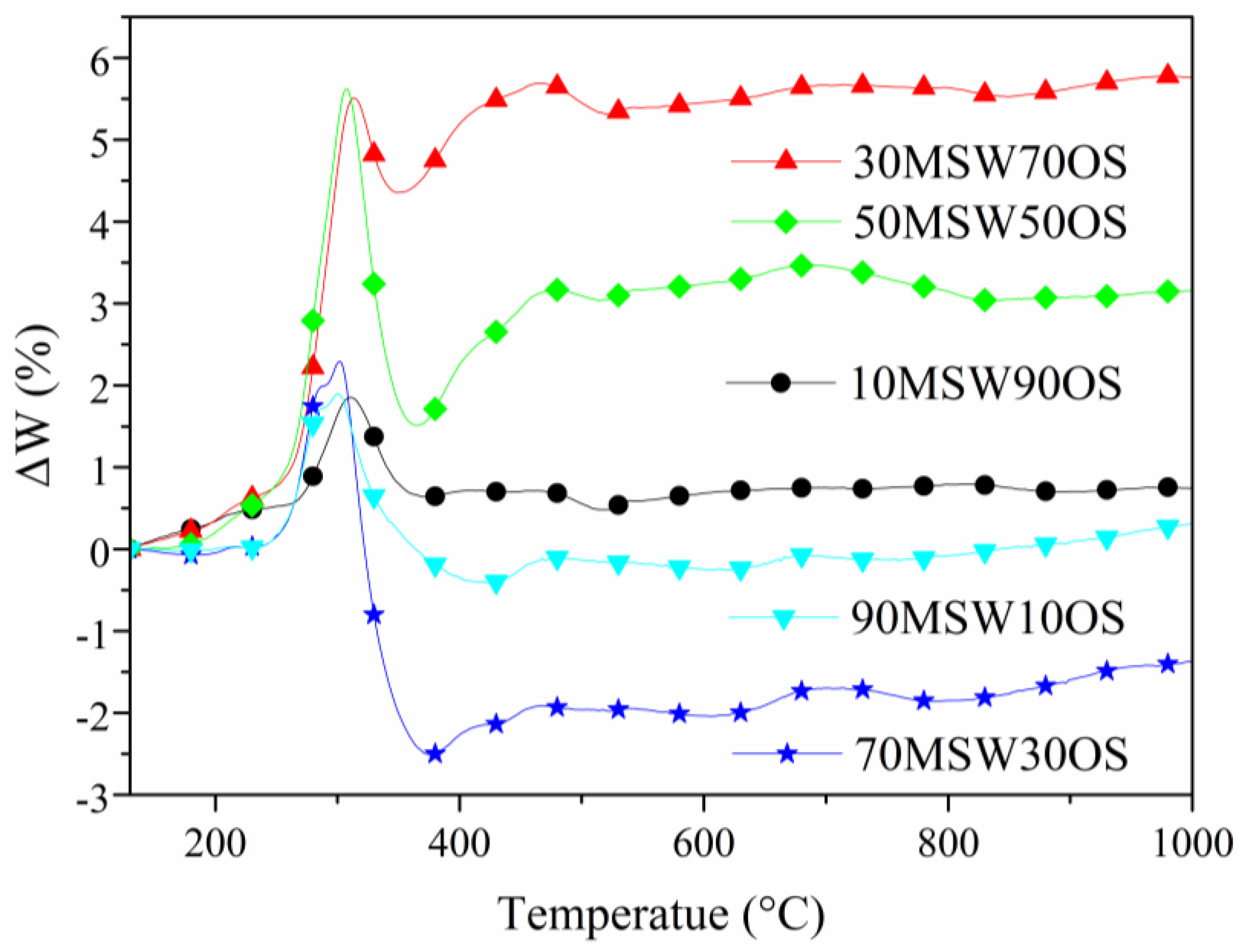

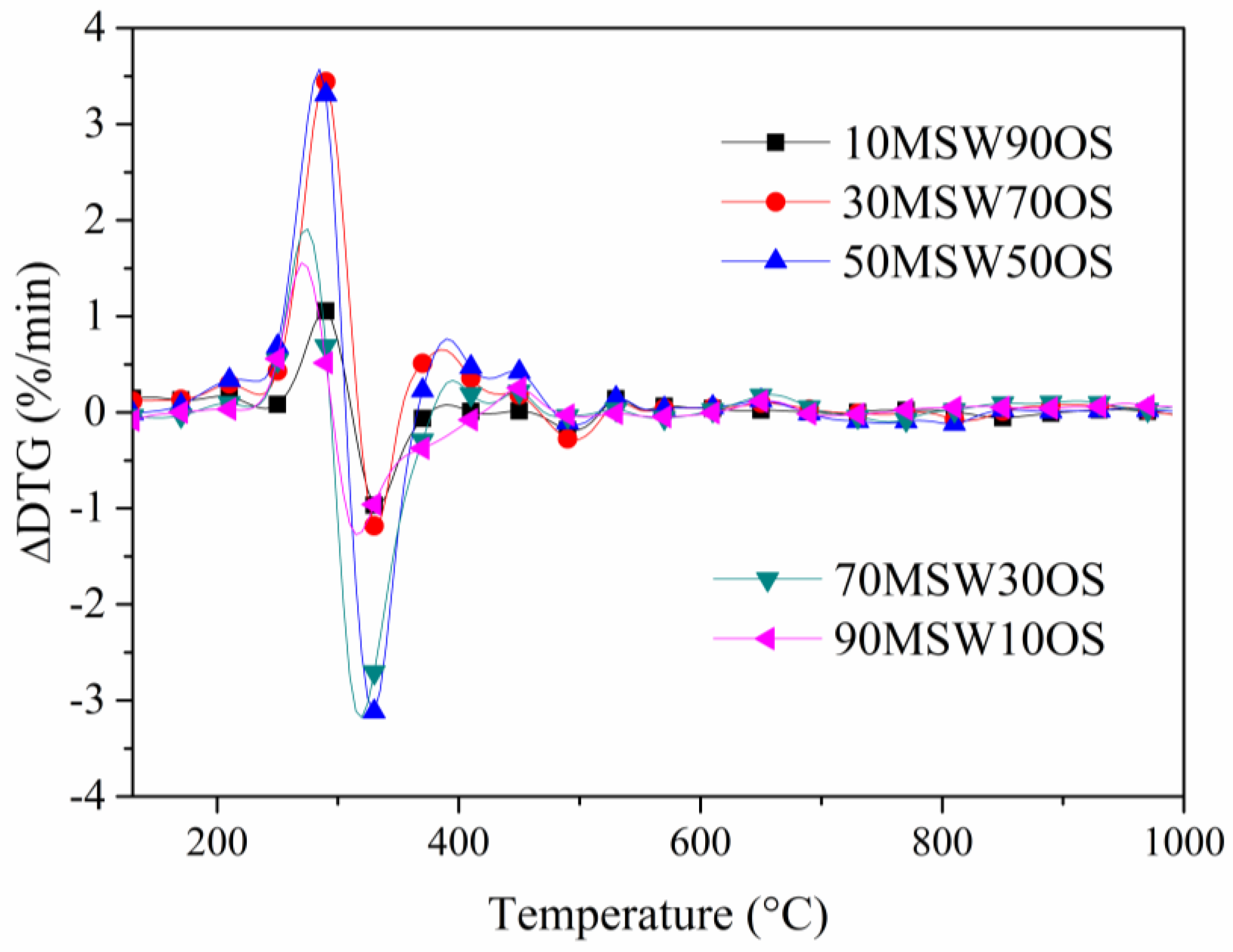

3.3. Interaction Between OS and MSW

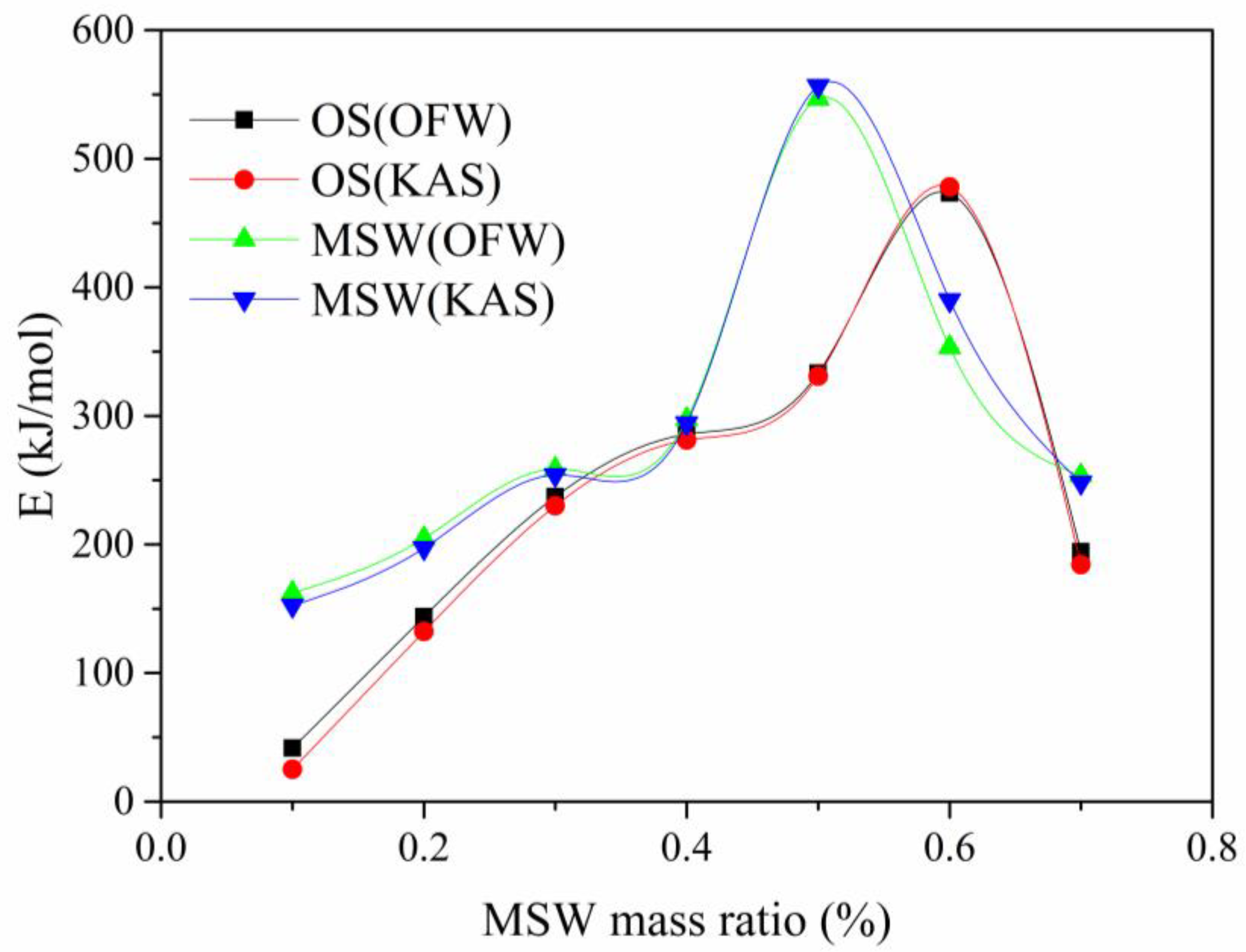

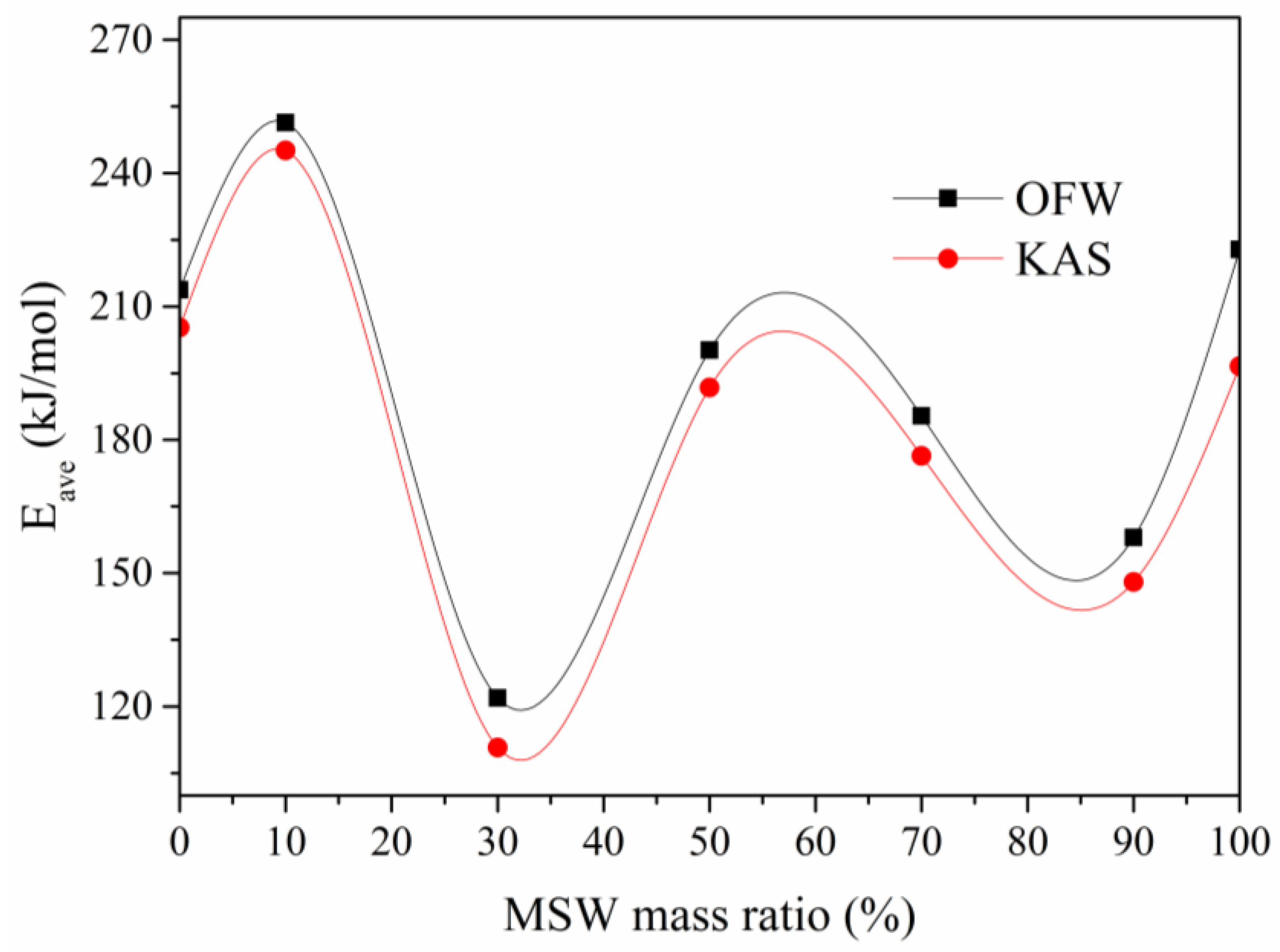

3.4. Kinetics Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSW | municipal solid waste |

| OS | oil shale |

| PVC | polyvinyl chloride |

| HHV | higher heating value |

| OFW | Ozawa–Flynn–Wall |

| KAS | Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose |

| TG | thermogravimetric |

| DTG | derivative thermogravimetric |

References

- Gritsch, L.; Breslmayer, G.; Rainer, R.; Stipanovic, H.; Tischberger-Aldrian, A.; Lederer, J. Critical properties of plastic packaging waste for recycling: A case study on non-beverage plastic bottles in an urban MSW system in Austria. Waste Manag. 2024, 185, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, A.; Yue, S.; Luo, Y.; Embaye, T.M.; Li, Z.; Ma, D.; Ruan, R.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z. Heavy metal enrichment characteristics and environmental risk assessment of MSW pyrolysis char and coal co-incineration fly ash. Fuel 2026, 404, 136236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics, N.B.O. China Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Yue, C.; Wu, J.; Teng, J. Pyrolysis characteristics of Longkou oil shale under optimized condition. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 125, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M. Evaluation of the porous structure of Huadian oil shale during pyrolysis using multiple approaches. Fuel 2017, 187, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackley, P.C.; Birdwell, J.E.; McAleer, R. Properties of solid bitumen formed during hydrous, anhydrous, and brine pyrolysis of oil shale: Implications for solid bitumen reflectance in source-rock reservoirs. Appl. Geochem. 2025, 185, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi-Khanghah, M.; Heris, S.Z.; Wongwises, S.; Mahian, O. Smart modeling of oil shale pyrolysis: Impact of feed composition and thermal parameters. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2026, 193, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi-Khanghah, M.; Wu, K.C.; Soleimani, A.; Hazra, B.; Ostadhassan, M. Experimental investigation, non-isothermal kinetic study and optimization of oil shale pyrolysis using two-step reaction network: Maximization of shale oil and shale gas production. Fuel 2024, 371, 131828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, X. Catalytic characteristics of the pyrolysis of lignite over oil shale chars. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 106, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Cao, H.; Wu, L.; Yang, F.; Fu, S.; Zhou, J. Effects of spatial distribution of tar-rich coal and oil shale and primary factors on product characteristics during microwave co-pyrolysis. Fuel 2025, 385, 134085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Mei, J.; Chen, J.; Zhu, T.; Fang, B. Study on the properties, by-products, and nitrogen migration mechanism of the co-pyrolysis of oil shale and waste tyres. Fuel 2024, 376, 132659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinadh, R.V.; Mahawar, R.; Neelancherry, R. Co-pyrolysis behaviour and synergistic effect of municipal solid waste components on biochar production through microwave-assisted co-pyrolysis. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 199, 107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S.; Dai, M.; Ma, X. Co-pyrolysis kinetics and behaviors of kitchen waste and chlorella vulgaris using thermogravimetric analyzer and fixed bed reactor. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakudze, S.; Chen, J. A critical review on co-hydrothermal carbonization of biomass and fossil-based feedstocks for cleaner solid fuel production: Synergistic effects and environmental benefits. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Yu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Hu, S.; Liao, Y.; Ma, X. Thermogravimetric analysis of the co-pyrolysis of paper sludge and municipal solid waste. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 101, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5373; Standard Test Methods for Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen in Analysis Samples of Coal and Carbon in Analysis Samples of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- GB/T 212-2008; Proximate Analysis of Coal. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Ahmad, S.; Zhu, X.; Wei, X.; Zhang, S. Influence of process parameters on hydrothermal modification of soybean residue: Insight into the nutrient, solid biofuel, and thermal properties of hydrochars. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y. An efficient method for the recovery of waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules: Solvent steam and pyrolysis techniques. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Yin, F. Co-pyrolysis of mixed plastics and its impact on kinetic parameters and pyrolysis product distribution. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 68, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coruh, M.K. Pyrolysis of oleaster seed under non-isothermal conditions to assess as bioenergy potential: Kinetic, thermodynamic and master plot analyses. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 198, 107861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Du, X.; Zhou, Y. Co-pyrolysis of medium-low maturity shale and nano-NiO catalyst under supercritical CO2 atmosphere: Mechanisms and reaction kinetics. Fuel 2025, 401, 135882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zuo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J. Thermal behavior and kinetic study on the pyrolysis of lean coal blends with thermally dissolved coal. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 136, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Luo, L.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X. Pyrolysis of superfine pulverized coal. Part 5. Thermogravimetric analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 154, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Liang, J.; Liao, Y.; Ma, X. Co-pyrolysis of chlorella vulgaris and kitchen waste with different additives using TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Song, M.; Dong, J.; Li, G.; Ye, C.; Hu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y. Synergetic effect of in-situ CaO on PVC plastic pyrolysis characteristics: TG and Py GC/MS analysis. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 234, 111205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Huang, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, H. Mechanism of radical-mediated synergy in co-pyrolysis of oil shale and yak dung: Experiments, kinetics and ReaxFF-MD simulations for cleaner energy production. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 205, 108501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liao, Y.; Guo, S.; Ma, X.; Zeng, C.; Wu, J. Thermal behavior and kinetics of municipal solid waste during pyrolysis and combustion process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 98, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.-M.; Lee, W.-J.; Chen, W.-H.; Lin, T.-C. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetics of co-pyrolysis of raw/torrefied wood and coal blends. Appl. Energy 2013, 105, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantelon, J.; Breillat, C.; Gaboriaud, F.; Alaoui-Sosse, A. Thermal degradation of Timahdit oil shales: Behaviour in inert and oxidizing environments. Fuel 1990, 69, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groune, K.; Halim, M.; Benmakhlouf, M.; Arsalane, S.; Lemee, L.; Ambles, A. Organic geochemical and mineralogical characterization of the Moroccan Rif bituminous rocks. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2013, 4, 472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, Z.; Ming, H.; Guo, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. TG-FTIR analysis of co-pyrolysis behavior between petroleum coke and model lignocellulosic biomass. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 122, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Hong, C.; Xing, Y.; Feng, W. Study on the co-pyrolysis characteristics and mechanism of sewage sludge and coconut shell. Thermochim. Acta 2025, 751, 180058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Kitchen Waste | Fruit Peel | Wood | Paper | Textile | PVC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass ratio (%) | 36.63 | 11.17 | 13.06 | 8.26 | 6.49 | 24.39 |

| Samples | MSW | OS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate analyses (wt. %, dry and ash-free basis) | C | 45.84 | 42.51 |

| H | 6.23 | 5.17 | |

| O 1 | 38.82 | 48.97 | |

| N | 1.55 | 1.20 | |

| S | 0.39 | 2.15 | |

| Proximate analyses (wt. %, dry basis) | Volatiles | 76.94 | 58.56 |

| Fixed Carbon | 15.74 | 3.45 | |

| Ash | 7.32 | 37.99 | |

| HHV (MJ/kg) | / | 19.19 | 15.26 |

| Blending Ratio | 100OS | 10MSW90OS | 30MSW70OS | 50MSW50OS | 70MSW30OS | 90MSW10OS | 100MSW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti (°C) | 414.4 | 284.9 | 268.7 | 264.1 | 261.5 | 258.8 | 255.4 |

| Tf (°C) | 800.7 | 847 | 869 | 872 | 888.6 | 898 | 913.5 |

| Mf (%) | 82.19 | 77.67 | 72.14 | 58.99 | 43.92 | 35.06 | 29.47 |

| DTG1 (%/min) | / | −1.99 | −4 | −8.85 | −14.96 | −18.8 | −22.48 |

| T1 (°C) | / | 327 | 318.5 | 311.5 | 301 | 297.5 | 297 |

| DTGmean1 (%/min) | / | −1.46 | −2.52 | −4.99 | −7.31 | −11.62 | −12.95 |

| DTG2 (%/min) | −4.66 | / | / | / | / | −4.89 | −5 |

| T2 (°C) | 470 | / | / | / | / | 378 | 377 |

| DTGmean2 (%/min) | −3.04 | / | / | / | / | −4.53 | −4.65 |

| DTG3 (%/min) | −1.54 | −4.5 | −4.6 | −4.55 | −4.87 | −5.02 | −5.48 |

| T3 (°C) | 525.5 | 469.5 | 468.5 | 466.5 | 463 | 460.5 | 458.5 |

| DTGmean3 (%/min) | −0.37 | −1 | −0.99 | −1 | −1 | −0.99 | −1 |

| Blending Ratio | 100OS | 10MSW90OS | 30MSW70OS | 50MSW50OS | 70MSW30OS | 90MSW10OS | 100MSW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔT1/2-1 (°C) | / | 56.6 | 63.9 | 65 | 58.3 | 46 | 38.5 |

| η1 (%) | / | 22.59 | 37.69 | 58.48 | 69.3 | 55.7 | 55.69 |

| D1 | / | 1.23 × 10−7 | 6.43 × 10−7 | 3.39 × 10−6 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 4.01 × 10−5 | 7.03 × 10−5 |

| ΔT1/2-2 (°C) | 48.4 | / | / | / | / | 32 | 40 |

| η2 (%) | 74.64 | / | / | / | / | 18.04 | 18.79 |

| D2 | 2.67 × 10−7 | / | / | / | / | 5.06 × 10−6 | 4.25 × 10−6 |

| ΔT1/2-3 (°C) | 12 | 78.8 | 66.6 | 64.3 | 57.1 | 61 | 54 |

| η3 (%) | 25.36 | 77.41 | 62.31 | 41.52 | 30.7 | 26.26 | 25.52 |

| D3 | 3.88 × 10−8 | 9.49 × 10−8 | 1.51 × 10−7 | 2.35 × 10−7 | 3.94 × 10−7 | 4.43 × 10−7 | 6.11 × 10−7 |

| D | 2.09 × 10−5 | 1.01 × 10−5 | 3.37 × 10−5 | 2.08 × 10−4 | 9.38 × 10−4 | 2.33 × 10−3 | 4.01 × 10−3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Xie, Y.; Gao, X.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lai, L. Characteristics and Kinetics of the Co-Pyrolysis of Oil Shale and Municipal Solid Waste Assessed via Thermogravimetric Analysis. Sustainability 2026, 18, 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020753

Chen L, Zheng L, Xie Y, Gao X, Lin Y, Yu Z, Lai L. Characteristics and Kinetics of the Co-Pyrolysis of Oil Shale and Municipal Solid Waste Assessed via Thermogravimetric Analysis. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020753

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lin, Liping Zheng, Yichun Xie, Xiongwei Gao, Yuxiang Lin, Zhaosheng Yu, and Lianfeng Lai. 2026. "Characteristics and Kinetics of the Co-Pyrolysis of Oil Shale and Municipal Solid Waste Assessed via Thermogravimetric Analysis" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020753

APA StyleChen, L., Zheng, L., Xie, Y., Gao, X., Lin, Y., Yu, Z., & Lai, L. (2026). Characteristics and Kinetics of the Co-Pyrolysis of Oil Shale and Municipal Solid Waste Assessed via Thermogravimetric Analysis. Sustainability, 18(2), 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020753