1. Introduction

Environmental innovation is vital to achieving economic objectives, especially amid rising environmental awareness and institutional pressures. Companies are increasingly recognizing that environmental innovation, defined as new products, processes, and organizational practices that reduce environmental impact, serves both as a moral obligation and a competitive edge. Additionally, research indicates that environmental innovation (EI) can enhance reputation among stakeholders, help institutions access green markets, and create a competitive advantage [

1]. At the same time, many institutions face financial constraints, such as limited access to external funding or insufficient internal resources, which may restrict their ability to pursue EI [

2]. Therefore, understanding how financially constrained organizations can leverage environmental innovation to gain a competitive advantage is important for both theory and practice.

Meanwhile, previous research has examined financial constraints and innovation beyond just the environmental context. For example, several studies focused on EU manufacturing SMEs and found that financial constraints reduce investment in environmental innovation, mainly due to higher risks, more extended payback periods, and uncertain profits associated with eco-innovation [

3]. Furthermore, research shows that institutions that engage in environmental innovation typically have greater latent financial needs, indicating that many environmental innovation projects remain unimplemented due to financial constraints [

4]. A recent study conducted in China revealed that green bond issuance boosts green innovation, with finance constraints mediating this effect, while environmental innovation influences this relationship [

5].

In line with the above supposition, evidence indicates that environmental innovation enhances competitive advantage [

6]. An example can be drawn from research conducted in Greece, which showed that both environmental product innovation and environmental process innovation enhance the competitive capabilities of medium and large enterprises [

7]. Additionally, Green innovation has demonstrated value during crises; for instance, Malaysian companies have utilized organizational, process, and marketing innovations to improve environmental, social, and financial performance, thereby strengthening their competitive advantage [

8].

Despite previous research’s contributions, several gaps persist. A careful exegesis of some studies shows that most studies have focused on the detrimental effects of financial constraints on innovation or how environmental innovation enhances performance or competitiveness. However, few specifically investigate how environmental innovation under financial constraints might yield a competitive advantage. Although some studies investigate financial constraints that influence environmental innovation, including studies on green bonds, the moderating effects of environmental regulations seem imminent. Moreover, there is limited understanding of how internal firm capabilities—such as management quality and governance—alongside external institutional pressures collectively impact these dynamics.

Aside from the above, considerable research focuses on specific sectors and individual nations, such as China and the EU, thereby limiting generalizability. The applicability of research findings across various industries, particularly those with varying capital intensities, both in developed and developing countries, remains unclear. Research on the dynamics of environmental innovation under severe financial constraints or during economic crises—such as recessions and pandemics—remains limited.

These discrepancies are of significant importance. Without understanding the whole trajectory—from constraints to ecological innovation to competitive edge—government and institutions may misunderstand how to promote sustainable business models. If environmental innovation is seen only as a cost during financial struggles, companies may avoid or delay green projects, jeopardizing sustainability objectives. Conversely, understanding the facilitating factors—such as internal capabilities and institutional pressures—can help organizations harness innovation to gain a competitive advantage, even with limited resources. Conducting this study is crucial, as companies rarely operate under ideal financial conditions. The ability to transform limitations into opportunities through innovation could determine long-term success and sustainability. Furthermore, policymakers and managers need data to support companies experiencing financial constraints, ensuring that sustainability is not a privilege reserved for well-capitalized enterprises.

Based on these premises, this study examines the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation, as well as the role of environmental innovation in mediating or moderating the path toward sustainable competitive advantage. It combines insights from strategic management, sustainability, and finance by analyzing how institutional pressures affect firms’ environmental innovation efforts, whether these efforts can turn constraints into competitive advantages, and which internal and external factors facilitate this transformation.

This study employs a strategic sustainability approach to analyze how environmental innovation serves as a vehicle for enterprises facing financial constraints to convert challenges into a competitive advantage. The research employs contemporary data, stringent methodology, and metrics of competitive advantage, financial, and market performance to yield practical insights.

This study offers several contributions. It connects finance (financial constraints), innovation (particularly environmental innovation), and strategic management (competitive advantage), and provides a comprehensive model of the interaction between sustainability and strategy under limits. The use of organizations from many industries and nations offers evidence of generalizability and examines the boundary circumstances under which environmental innovation influences competitive advantage.

It outlines internal capacity levers, such as management quality and governance. It also considers external constraints, including regulations and laws that organizations may utilize. Also, it provides guidelines for managers working in limited contexts and offers recommendations for governmental actions to encourage green innovation. It addresses the lack of research on the strategic advantage of environmental innovation under financial constraints, rather than focusing only on the costs. This study examines the relevant research question:

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature Review

Prior research acknowledges that financial constraints hinder organizations’ innovation endeavors. Research in developing nations shows that companies experiencing financial constraints are significantly less likely to pursue product or process innovation, particularly if they are small or have limited access to external funding and collateral [

9]. Likewise, many researchers employed direct survey metrics to assess financial constraints within established French enterprises; the authors found that such constraints significantly reduce the likelihood of firms engaging in innovative activities [

10]. Research on EU manufacturing SMEs indicates that financial constraints directly hinder the adoption of environmental innovations, primarily due to high technical risk, extended payback periods, and unclear returns [

10].

Recent research examines strategies that may alleviate or improve this adverse association. A recent study found that R&D human capital in Korean manufacturing firms mitigates the negative impact of financial constraints on product and service innovation. However, this protective effect diminishes at increased levels of R&D intensity [

11]. A similar study from Asia, specifically China, suggests that green bonds promote green innovation, with financial constraints serving as a mediating factor; on the other hand, environmental innovations and ownership frameworks diminish the magnitude of these advantages [

12]. Another study indicated that green finance regulations in China could alleviate financial constraints on green innovation, while privately owned businesses typically have a diminished advantage [

13].

Research already shows that environmental innovation, often referred to as green innovation, significantly impacts competitive advantage and improves company performance. Research also shows that green innovation correlates well with competitive advantage, with this relationship being mediated by organizational learning [

14]. Additionally, there are assertions that stakeholder and policy demand positively alleviate this mediating effect [

15]. Meanwhile, research shows that Porter’s theory corroborates this assumption [

15].

In other studies, some researchers investigated Chinese companies and found that green innovation improves (management quality) organizational performance [

16]. Similarly, some authors contend that the nature of competitive strategy (differentiation versus cost leadership) significantly affects the impact of green innovation on performance [

17]. Specifically, a differentiation strategy intensifies the impact of green product innovation on performance, whereas a cost leadership strategy amplifies the effect of green process innovation. In China’s industrial sector, green supply chain firms have shown that environmental innovation, as evidenced by patent activity, is associated with enhanced competitive performance when financing is increased and constraints are minimized [

18]. Research indicates that environmental innovation provides benefits, such as improved reputation, cost-effective regulatory compliance, and increased resilience in competitive markets when environmental standards become differentiators due to consumer preferences or regulations [

19].

2.2. Exegesis of Literature

Examining these studies, there are a few takeaways, as various studies indicate agreement on several aspects. First, nearly all empirical studies show that increased restrictions, evaluated by financial constraints, challenges in obtaining external funding, and significant hurdles to financing, diminish innovative activity [

20]. These empirical claims indicate that human capital, as well as institutional policies such as green finance, subsidies, regulation, and governance, often serve as moderating or mediating factors that may alleviate the negative impacts of financial constraints [

21]. Importantly, research indicates that the amount and impact of effects often vary by business size, age, sector ownership, region, and institutional pressures [

22].

Nonetheless, a few disparities arise. Some studies indicate that financialization hinders green innovation by diverting resources toward immediate financial returns rather than long-term sustainable research and development, especially within significantly polluting companies [

23]. Some individuals believe that policies and green funding mechanisms can alleviate such repression and facilitate eco-innovation, particularly when supported by favorable regulations and management skills [

24]. Certain studies employ indirect proxies, such as cash flow sensitivity and leverage ratios, while others utilize direct survey measurements; this influences the consistency and comparability of the findings [

25,

26,

27].

As a result, numerous gaps become evident. For instance, some studies suggest that financial constraints hinder innovation, while others demonstrate a correlation between environmental innovation and improved company performance. Nevertheless, few explicitly outline the approach. The mediating role of emotional intelligence in restricted environments remains inadequately studied. Furthermore, research often examines one moderator at a time, such as human capital or policy. There is a scarcity of research that simultaneously examines several moderators, such as managerial quality, governance, institutional frameworks, and stakeholder pressure, at least to explore their interactions in facilitating innovation under constraints.

Moreover, most studies focus on China, the European Union, and the South Korean industry. Research addressing several sectors, including services, technology, major polluters, small and medium enterprises, large corporations, and varied institutional frameworks, is limited. This limits the understanding of boundary conditions. Additionally, there is a scarcity of studies on business sustainability during crises such as economic recessions and pandemics, on environmental innovation under constraints, and on the sustainability of competitive advantages gained during these periods. Notably, while financialization, green bonds, internal finance, and subsidies have been examined, direct indicators of financial distress, such as non-performing corporate loans or bank exposures in non-banking firms, are limited. Similarly, direct metrics of environmental innovation output in constrained firms linked to competitive advantage are underdeveloped.

This study seeks to characterize environmental innovation as an intermediary between financial constraints and competitive advantage, illustrating that financial constraints hinder creativity and, consequently, performance, whereas restricted innovation enhances competitive advantage. This study seeks to integrate internal capabilities such as management quality, governance, and R&D capacity, with external pressures, including institutional, regulatory, and stakeholder influences, into a unified model to ascertain the conditions under which the negative impacts of limitations are alleviated. This research utilizes numerous firms and countries, both developed and emerging, to investigate boundary conditions and the relevance of the findings.

Addressing these gaps is essential, as understanding the function of environmental innovation under constraints is increasingly important during economic instability and sustainability demands. Businesses and government require sophisticated models to determine when and how ecological innovation can serve as a source of competitive advantage rather than merely an expense. In the absence of this, there is a risk that sustainability becomes simply rhetoric for limited firms or that policy support is misallocated. This study develops a model showing that financial constraints adversely affect environmental innovation, which, in turn, mediates the achievement of competitive advantage. This research examines the moderating effects of internal company capabilities and external factors.

2.3. Theoretical Framework

This study’s theoretical framework integrates three interconnected perspectives: Institutional Theory, the Resource-Based View (RBV), and Stakeholder Theory. These theories clarify how firms facing financial constraints can leverage environmental innovation (EI) to achieve business sustainability and competitive advantage. These theories collectively elucidate the intricate interplay between financial constraints, strategic innovation decisions, and environmental factors such as management quality and institutional pressures. The integrated approach enhances understanding of how internal capabilities and external environments affect a firm’s ability to transform financial constraints into strategic benefits.

Institutional Theory clarifies how organizations respond to external pressures such as regulatory authorities, social expectations, and cultural norms to achieve legitimacy and sustain their existence [

28]. Organizations function within institutional realms defined by coercive, normative, and mimetic influences. Institutional theory asserts that organizations adopt ecologically innovative practices not only for financial benefits but also to achieve social legitimacy and comply with regulatory requirements. Despite financial constraints, significant institutional pressures may compel organizations to engage in sustainability projects.

This study proposes that institutional pressures serve as an external moderator, alleviating the adverse effects of financial constraints on environmental innovation. When regulatory frameworks and public expectations are strong, organizations are more likely to engage in eco-innovation despite limited financial resources, as failing to do so incurs reputational and legal repercussions. Thus, institutional theory provides a framework for understanding why organizations engage in environmental innovation despite economic challenges.

The three theoretical lenses are not merely juxtaposed; they jointly explain how firms transform financial constraints into sustainable competitive advantage. Institutional Theory clarifies why firms must pursue environmental innovation to maintain legitimacy under coercive and normative pressures [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The Resource-Based View specifies how internal capabilities—such as management quality and the ability to reconfigure scarce resources—allow firms to respond to these pressures by developing valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) eco-innovations [

33,

34]. Stakeholder Theory links external legitimacy and internal capabilities by suggesting that firms that satisfy stakeholders’ environmental expectations are rewarded with trust, reputation, and preferential access to resources [

35].

In this way, institutional pressures generate a need to change, RBV highlights the capacity for change, and Stakeholder Theory explains the rewards of change. Our hypotheses reflect this integration: H1 and H2 capture the fundamental constraint–innovation–performance mechanism; H3 and H4 focus on how internal capabilities (MQ) and external legitimacy pressures (IP) reshape the effect of financial constraints; H5–H7 show how environmental innovation acts as a bridge between constrained resources, stakeholder expectations, and sustained competitive advantage.

Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Formulation

Contemporary enterprises operate within an increasingly complex business environment characterized by volatile markets, resource scarcity, and increased sustainability demands. Financial constraints, defined by limitations in obtaining adequate internal or external resources for investment, have consistently been recognized as barriers to corporate innovation [

36]. When capital is limited, managers generally prioritize operational sustainability above long-term innovative investments, particularly in environmental innovation projects that may require high upfront costs and a prolonged payback period.

Recent studies indicate that environmental innovation (EI), the development of sustainable products, processes, and organizational practices, can transform financial pressure into a strategic advantage by enhancing efficiency, reputation, and market distinction [

37,

38]. Consequently, EI serves as a strategic channel enabling selected firms to achieve business sustainability and competitive advantage.

The ability to exercise emotional intelligence during financial stress depends mainly on internal and external factors. The quality of management, defined by leadership skills, experience, and strategic insight, determines the effective allocation of scarce resources to innovation [

39]. External institutional influences, such as legislative requirements, societal norms, and issues of cognitive validity, influence organizational behavior toward sustainability [

39]. These factors facilitate the connection between financial constraints and innovation, determining whether businesses yield to or overcome resource shortages. Integrating insights from Resource-Based View (RBV), Institutional Theory, and Stakeholder Theory, this study proposes a conceptual model presented in

Figure 1.

In this framework, financial constraints negatively affect environmental innovation, which in turn improves business sustainability and competitive advantage. The quality of management and institutional pressures influences the first connection, either intensifying or alleviating the negative impacts of constraints. Environmental innovation acts as an intermediary connecting resource scarcity to sustainable competitive outcomes, as acknowledged by research [

40]. Financial constraints hinder an organization’s ability to spend on research and development, technology acquisition, and process enhancement, all of which are essential for environmental innovation [

3]. When organizations encounter financial constraints, their innovation portfolios generally contract to projects with shorter payback periods and less risk [

41]. Empirical studies across European and Asian contexts indicate that financial constraints significantly reduce the likelihood of implementing eco-innovations [

42]. Moreover, companies with high debt levels or limited access to capital markets often prioritize financial stability above sustainability initiatives, thereby reinforcing a resource-constrained rationale [

43]. Thus, financial constraints are expected to negatively affect environmental innovation.

H1. Financial constraints negatively affect environmental innovation.

Environmental innovation enhances companies’ economic benefits by reducing operating expenses, thereby improving resource efficiency, meeting stakeholder expectations, and distinguishing products in more eco-conscious marketplaces [

12]. Companies that adopt eco-friendly practices also achieve greater regulatory compliance and brand credibility, fostering long-term sustainability [

10]. Recent research in China and Greece reveals that green innovation significantly improves profitability, environmental performance, and market competitiveness [

9,

10,

12]. Consequently, environmental innovation functions as a strategic tool that connects sustainability objectives with improved business outcomes. This study hypothesizes that

H2. Environmental innovation positively influences business sustainability and competitive advantage.

While financial constraints tend to depress environmental innovation (H1), environmental innovation is expected to enhance business sustainability and competitive advantage (H2). However, firms do not operate in a vacuum. The extent to which financial constraints suppress eco-innovation depends on both internal capabilities and the external institutional environment [

15]. Management quality reflects the internal ability to reconfigure scarce resources [

13], prioritize long-term projects and implement complex environmental initiatives, whereas institutional pressures capture the external regulatory and normative demands that make eco-innovation more salient and legitimate [

14]. We therefore consider management quality and institutional pressures as two complementary forces that can reshape the impact of financial constraints on environmental innovation.

H3. Management quality positively moderates the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation, such that the adverse effect of financial constraints on environmental innovation is weaker in firms with higher management quality.

Institutional pressures—coercive regulations, industry-normative standards, and societal legitimacy demands—compel organizations to engage in environmental innovation despite financial constraints. Regulatory measures, such as environmental standards and emission targets, often require compliance-driven innovation; however, normative pressures from consumers, investors, and NGOs create reputational incentives for sustainable practices. An empirical study in China demonstrates that environmental regulation affects the relationship between financial constraints and green innovation by alleviating uncertainty and signaling governmental support [

22]. This study foresees that robust institutional frameworks can mitigate the detrimental effects of economic constraints, enabling businesses to sustain environmental innovation.

H4. Institutional pressures positively moderate the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation, such that the adverse effect of financial constraints on environmental innovation is weaker in more stringent institutional environments.

Despite financial constraints that may limit investment capacity, companies that overcome these challenges through environmental innovation can turn them into opportunities. This aligns with the Porter Hypothesis, which posits that well-structured environmental programs may enhance competitiveness by promoting efficiency and innovation [

23]. Empirical evidence shows that companies that implement green innovation achieve improved financial and environmental outcomes, even when facing resource constraints [

25]. This study anticipates that environmental innovation serves as a mediating mechanism linking financial constraints to increased sustainability and competitiveness.

Management quality and institutional pressures are conceptually distinct but complementary moderators. Management quality captures internal capabilities and governance arrangements that allow firms to reconfigure resources and prioritize eco-innovation even under tight financial conditions. Institutional pressures reflect the external regulatory and normative environment that increases the salience and urgency of environmental performance.

Taken together, these moderators represent two sides of the exact adaptive mechanism: internal capacity (MQ) and external demand (IP). High management quality can help firms interpret and strategically respond to intense institutional pressures, while stringent institutional environments increase the pay-off from investing in internal capabilities. Our empirical models, therefore, estimate the moderating roles of MQ and IP separately (H3 and H4). However, the underlying theoretical logic is that they operate in a complementary fashion: each can attenuate the adverse effect of financial constraints on environmental innovation on its own, and their combined presence is expected to be particularly favorable to eco-innovation.

H5. Environmental innovation mediates the relationship between financial constraints and business sustainability/competitive advantage.

Firms with stronger managerial capabilities/resources are better able to plan, finance, and implement environmental innovation initiatives. Evidence from studies shows that firms with more capable and better-managed leadership teams tend to develop and deploy the resources needed for environmental innovation, which translates into higher levels of such innovation [

39,

40]. This study expects that management quality has a positive effect on environmental innovation. This is hypothesized as

H6. Management quality positively affects environmental innovation.

An exegesis of prior studies suggests that coercive and normative pressures from regulators, industries, and peers encourage firms to adopt and develop environmental innovation policies. Similarly, external pressures from regulators, professional bodies, and industries push firms to adopt environmental practices and related innovations. On this premise, it is hypothesized that greater institutional pressure could be associated with greater environmental innovation [

28]. This supposition is based on the premise that firms that may not initially engage in environmental innovation may be pressured to do so by several institutions [

39]. Given this, this study hypothesizes that institutional pressures can positively affect environmental innovation. The hypothesis is presented thus:

H7. Institutional pressures (coercive and normative) positively affect environmental innovation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative, explanatory, and cross-country panel design to examine how financial constraints influence environmental innovation and, in turn, how environmental innovation enhances business sustainability and competitive advantage. The study investigated how management quality and institutional pressures moderate the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation.

A longitudinal (panel) research design was chosen to capture temporal variations in financial conditions, innovation investment, and sustainability outcomes. The design allowed for controlling firm-specific unobservable heterogeneity and enhances causal inference [

44]. This quantitative approach aligned with prior empirical studies linking financial constraints, innovation, and sustainability.

3.2. Population and Sample

The study focuses on publicly listed enterprises operating in environmentally relevant and capital-intensive sectors. The sampling frame comprised firms from six countries representing both developed and emerging economies, observed over the period 2012–2024. Target industries include manufacturing, energy and utilities, transportation and logistics, technology and telecommunications, and financial and business services. These sectors were selected because they (i) exhibit significant environmental impacts, (ii) are subject to increasing regulatory and stakeholder pressure, and (iii) report relatively rich financial and sustainability data. Firms were selected using the following inclusion criteria:

The firm is publicly listed on a major stock exchange in one of the six countries. It has continuous annual data on core financial indicators, environmental innovation measures, and ESG/sustainability metrics over at least five consecutive years from 2012 to 2024.

The firm exhibits evidence of innovation or sustainability engagement, as indicated by non-zero R&D expenditure, disclosed environmental or sustainability reports, and/or recorded environmental patents.

The firm’s financial statements and ESG data are internally consistent (no apparent accounting anomalies) and comparable over time. Firms with missing key variables or extreme inconsistencies were excluded.

The final balanced/unbalanced panel consists of approximately 280 firms, yielding a multi-year panel of firm–year observations. To enhance cross-country comparability, financial variables were converted to a common currency using annual average exchange rates and, where necessary, adjusted for inflation. Extreme outliers in continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

To assess comparability across firms and industries, we documented the distribution of sample firms by country, sector, and size class (small/medium vs. large, based on total assets and sales). This design ensures that the sample captures both cross-country variation in institutional environments and cross-industry differences in environmental exposure, while maintaining sufficient within-firm variation over time to estimate panel models as suggested by similar studies [

3,

25,

38].

3.3. Data Sources

Firm-level financial and accounting data were obtained from Thomson Reuters Eikon and Orbis databases, which provide harmonized annual statements for listed companies. We collected annual firm-level financial, innovation, and ESG information for the period 2012–2024. Missing values were handled by requiring at least five consecutive years of data per firm; firms with excessive missingness were dropped. Extreme outliers were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. To ensure comparability across industries, we restrict the sample to five major sectors—manufacturing, energy, financial services, technology, and transportation—and create industry dummies for each sector. Firm size in the sample ranges from medium-sized enterprises to large multinationals, reflecting a diverse industrial composition.

Environmental patents were collected from international patent databases and matched to firms through standardized identifiers. ESG and sustainability indicators, including environmental performance scores and innovation-related metrics, were sourced from reputable ESG providers and companies’ own sustainability reports. Country-level institutional indicators were drawn from the World Bank Governance Indicators and the OECD Environmental Policy Stringency database.

3.4. Variable Measurement

Financial Constraints (FC): Financial constraints are measured using a composite index that captures firms’ difficulty in obtaining or servicing external finance. Specifically, we combine: (i) the leverage ratio (total debt/total assets), (ii) the interest coverage ratio (EBIT/interest expense, reverse-coded so that lower coverage indicates tighter constraints), and (iii) a cash-flow sensitivity measure (operating cash flow/total assets, reversed where appropriate). Each component is winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles, standardized (z-scores), and then averaged to form a continuous index. Higher FC values indicate more severe financial constraints. In addition to robustness checks, we construct an alternative financial distress indicator based on low-interest-coverage thresholds and, where available, non-performing loan information; the results are qualitatively similar.

Environmental Innovation (EI): Environmental innovation is captured through a composite EI index that reflects both technological and strategic eco-innovative efforts, which includes the (logarithm of) annual environment-related patent counts assigned to each firm, and an environmental innovation/eco-efficiency score derived from ESG ratings and sustainability reports. Patent-based indicators capture formal technological innovation, while ESG innovation scores capture broader organizational and process-related innovation, such as cleaner production practices, resource efficiency programs, and environmental management systems. In this way, our EI construct reflects a portfolio of product-, process- and organization-oriented environmental innovations, rather than a single indicator. Both components are normalized to a 0–1 scale and averaged. Higher EI values indicate a greater intensity of eco-innovation. Where patent classification allows, we distinguish between environmental product and process patents and compute two sub-indices (EI_product, EI_process). In additional regressions, both EI dimensions show positive relationships with business sustainability and competitive advantage; the patterns are broadly consistent with the main EI index, although process innovation tends to be more strongly associated with cost-related outcomes and product innovation with market-related outcomes.

Management Quality (MQ): Management quality is operationalized as a composite governance and capability index at the firm level. It combines Board independence (percentage of independent directors), Board diversity (e.g., share of women on the board), CEO tenure (years in position), and a management efficiency indicator (such as sales per employee or an operating efficiency ratio). Each indicator is standardized and averaged to create a continuous MQ score; higher MQ values represent higher management quality. Although many of these governance characteristics are qualitative, they are inherently recorded as numerical percentages or counts, making them suitable for econometric modeling.

Institutional Pressures (IPs): Institutional pressures are measured at the country–year level and capture the regulatory and normative context in which firms operate. We constructed an IP index by standardizing and averaging the regulatory quality and rule of law dimensions of the World Bank Governance Indicators and the OECD Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) score. The resulting IP index ranges approximately from low to high stringency; higher IP values indicate stronger coercive and normative pressures for environmental performance. This originally qualitative institutional environment is thus represented numerically and can be incorporated into econometric models.

Business Sustainability (BS): Business sustainability is proxied using the environmental and social pillars of ESG scores for each firm–year. These scores are rescaled to a 0–1 interval and averaged to form a BS index. Higher BS values indicate stronger sustainability performance in environmental and social dimensions.

Competitive Advantage (CA): Competitive advantage is captured through a combined performance index based on return on assets (ROAs) and Tobin’s Q (market value/replacement cost of assets). Both indicators are winsorized, standardized, and averaged to construct a CA index, where higher values denote a stronger sustainability-oriented competitive position. For some specifications, BS and CA are combined into an integrated BS/CA index to capture sustainability-linked competitive performance outcomes in a single dependent variable.

Control Variables: Several firm-level controls were included to isolate the relationships of interest. These variables include the following. Firm Size: natural logarithm of total assets (in constant currency units); Firm Age: number of years since the last listing on a stock exchange; R&D Intensity: R&D expenditure divided by total sales (percentage); Leverage: total debt/total assets (also used as one component of the FC index); Industry Dummies: a set of binary variables indicating the firm’s primary industry such as manufacturing, energy, financial services, technology, transportation), with one sector serving as the reference category.

All qualitative attributes (such as sector membership and country institutional context) are transformed into numerical dummy variables or standardized indices, ensuring that only quantitative variables enter the econometric models. Before estimation, continuous variables are checked for skewness, winsorized where necessary, and standardized in some specifications to facilitate the interpretation of interaction and mediation effects.

3.5. Analytical Strategy

The study employed panel regression modeling to test the hypotheses and evaluate both direct and moderated relationships. Thereafter, moderation and mediation testing were conducted. In addition, to assess potential reverse causality—namely, whether higher business sustainability and competitive advantage might themselves ease financial constraints—we estimate an auxiliary dynamic panel model with financial constraints as the dependent variable and lagged BS/CA as a key predictor, using the same GMM framework. This specification allows us to test whether improvements in sustainability performance feed back into firms’ financing conditions, while maintaining consistency with the identification strategy used in the main models. To ensure robustness and address potential endogeneity and autocorrelation, several analytical techniques were applied sequentially. The first was the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. The descriptive analyses summarized central tendencies and dispersion. At the same time, correlation matrices were used to test for multicollinearity among variables. Afterwards, panel regression analysis was conducted to compare fixed effects (FEs) and random effects (REs) estimations using the Hausman test to determine the appropriate specification [

45]. Dynamic panel estimation was conducted to address endogeneity between financial constraints and innovation.

The study applied the system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator, as suggested in the literature [

46]. GMM was used to control for simultaneity bias and firm-level unobserved effects. For the dynamic panel estimation, we employ the system GMM estimator. Endogenous regressors (FC and EI) were instrumented using their own lagged levels and differences (starting at lag t–2) following Arellano–Bover and Blundell–Bond. Management quality, institutional pressures, and control variables were treated as predetermined or exogenous, depending on specification. We restricted the number of instruments by collapsing the instrument matrix to avoid overfitting. Post-estimation diagnostics indicated no second-order serial correlation (AR(2) test

p > 0.10) and acceptable instrument validity (Hansen test

p-values between 0.25 and 0.60), suggesting that our instruments are appropriate.

To test the mediating role of environmental innovation (H5), we followed the causal steps approach and estimated Model (3). Additionally, we computed the indirect effect of FC on BS/CA through EI and obtained bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5000 resamples. The mediation was considered significant if the 95% CI of the indirect effect did not include zero. For the moderation, interaction terms (FC × MQ; FC × IP) were tested to ascertain whether management quality and institutional pressures weaken the negative relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation, as claimed across broader studies [

46,

47].

To operationalize the moderating roles of management quality and institutional pressures, we estimated two interaction models: one including the FC × MQ term (H3) and another including the FC × IP term (H4). Estimating these moderators in separate specifications avoids excessive multicollinearity between MQ and IP and preserves the interpretability of the interaction terms, given our sample size and number of controls. Conceptually, the two models represent different slices of the exact mechanism—internal capability versus external demand—which we interpret jointly in the discussion.

On the other hand, mediation was tested to determine the indirect effect of financial constraints on business sustainability through environmental innovation using bootstrapping techniques to estimate mediation significance. Furthermore, robustness checks were applied as alternative measures of financial constraints (such as leverage and liquidity), and environmental innovation (for example, patents and R&D intensity) was used to ensure consistency.

It is worth noting that we also estimated supplementary regressions using alternative specifications of financial constraints (including interest coverage and liquidity ratios alongside leverage) and alternative normalizations of the environmental innovation index. These robustness checks yield coefficients with the same sign and similar magnitude, suggesting that a particular operationalization of the constructs does not drive our key inferences.

To explore contextual heterogeneity without over-complicating the main specification, we conduct supplementary subsample estimations. Specifically, we re-estimate the moderating models for (i) high-emission versus low-emission industries and (ii) firms located in more versus less stringent institutional environments. These analyses allow us to assess whether the moderating roles of management quality and institutional pressures are stronger in particular sectors or country contexts, while keeping the core empirical framework unchanged. For brevity, we summarize these findings in the discussion.

3.6. Model Specification

The baseline model for hypothesis testing was expressed as:

EI is the Environmental Innovation Index (standardized 0–1 composite based on green patent counts per firm-year and ESG “innovation” scores).

FC is the Financial Constraints index (a standardized composite of leverage ratio, interest coverage ratio, and cash flow sensitivity; higher values = more constrained).

MQ is the Management Quality Index (a standardized composite of board independence, CEO tenure, executive experience, and efficiency metrics).

IP is the Institutional Pressures index (standardized composite based on World Bank Governance Indicators and OECD Environmental Policy Stringency scores at the country level). BS/CA is Business Sustainability/Competitive Advantage index (standardized composite of ESG performance scores and financial/market-based performance—ROA and Tobin’s Q).

Controls are firm size (log of total assets), Firm Age (years since listing), R&D Intensity (R&D expenditure/sales), Leverage (total debt/total assets), and industry dummy variables (0/1).

μi represents the unobserved firm-specific effects.

ϵit is the idiosyncratic error term.

The mediation effect will be confirmed if (a) FC significantly predicts EI, (b) EI significantly predicts BS/CA, and (c) the direct effect of FC on BS/CA diminishes when EI is included.

3.7. Expected Validity and Reliability

The reliability of financial and innovation indicators was ensured through the use of standardized databases (Eikon, Orbis, and OECD). Construct validity was supported by established operational measures from prior research [

48,

49]. Statistical tests, such as the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and robustness checks enhanced internal validity and minimized measurement bias. As an additional validity check, we examined firm-year cases where patent-based environmental innovation is zero but ESG-based environmental innovation scores are positive; these usually correspond to process or organizational innovations. The study considers several forms of environmental innovation (EI), such as the adoption of ISO 14001:2015 Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use [

50] and eco-efficiency programs, suggesting that the combined EI index indeed captures a broader spectrum of eco-innovative activities beyond patent-based indicators.

4. Findings

This section presents the empirical results of the study, examining the relationship between financial constraints, environmental innovation, and business sustainability/competitive advantage, and the moderating roles of management quality and institutional pressures. The analysis draws on panel data covering 280 firms across six countries from 2012 to 2024. The results were organized into three parts: (1) variance inflation factor (VIF) results, (2) robustness checks, (3) descriptive statistics and correlations, (4) regression results for direct effects, moderation, and mediation analysis, and (5) hypothesis testing summary.

Table 1 presents the variance inflation factor (VIF) results. The VIF values for all predictors range from 1.2 to 2.3, well below the conventional threshold of 5 or the stricter 3.3 suggested across the literature. Tolerance values were above 0.30, indicating that each variable shares limited variance with others. This implies that multicollinearity was not a concern in this dataset; therefore, regression coefficients are stable, and each construct contributes unique explanatory power. The predictors (financial constraints, management quality, and institutional pressures) were distinct constructs, providing support for the measurement model’s discriminant validity.

Table 2 presents the robustness checks across seven model specifications. Regarding internal validity and measurement bias, the table shows that across all seven models, the signs and significance of the coefficients remained stable, reinforcing internal validity and minimizing measurement bias. Even when alternative measures (leverage, lagged FC) or estimation methods (FE, SEM, and GMM) were used, the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation remained negative and significant. This stability suggests that specific variable scaling, omitted-variable bias, or endogeneity does not drive the results. R

2 values range from 0.41 to 0.58, suggesting moderate-to-strong explanatory power for social science research standards, indicating that the model captured a meaningful proportion of variance in environmental innovation and business sustainability.

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and pairwise correlations of the principal variables. The results demonstrate a negative correlation of −0.42 between Financial Constraints and Environmental Innovation, suggesting that enterprises under higher financial pressure are likely to spend less on environmental innovation. In contrast, Environmental Innovation shows a positive correlation with Business Sustainability/Competitive Advantage (0.61), supporting the anticipated mediating role. Management Quality (0.39) and Institutional Pressures (0.41) have positive relationships with Environmental Innovation, indicating possible moderating effects.

Table 4 summarizes the regression analysis findings. The hypotheses were evaluated by panel regression and hierarchical moderation models. The results are shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Model 1 indicates that financial constraints exert a substantial negative impact on environmental innovation (β = −0.371,

p < 0.001), hence validating H1. Model 2 demonstrates that environmental innovation substantially improves corporate sustainability and competitive advantage (β = 0.523,

p < 0.001), hence validating H2.

Including environmental innovation as a mediator reduces the Financial Constraints coefficient on Business Sustainability from −0.198 to −0.122, achieving marginal significance, indicating partial mediation and corroborating H5. This indicates that environmental innovation serves as a conduit through which financial constraints influence corporate sustainability results.

Beyond the relationships captured in H1–H5, Model 1 in

Table 4 also shows that management quality and institutional pressures have statistically significant and positive effects on environmental innovation (β_MQ ≈ 0.17,

p < 0.01; β_IP ≈ 0.14,

p < 0.05). These findings support H6 and H7, indicating that firms with higher-quality management and operating under stronger institutional pressures tend to exhibit higher levels of environmental innovation. These are illustrated in

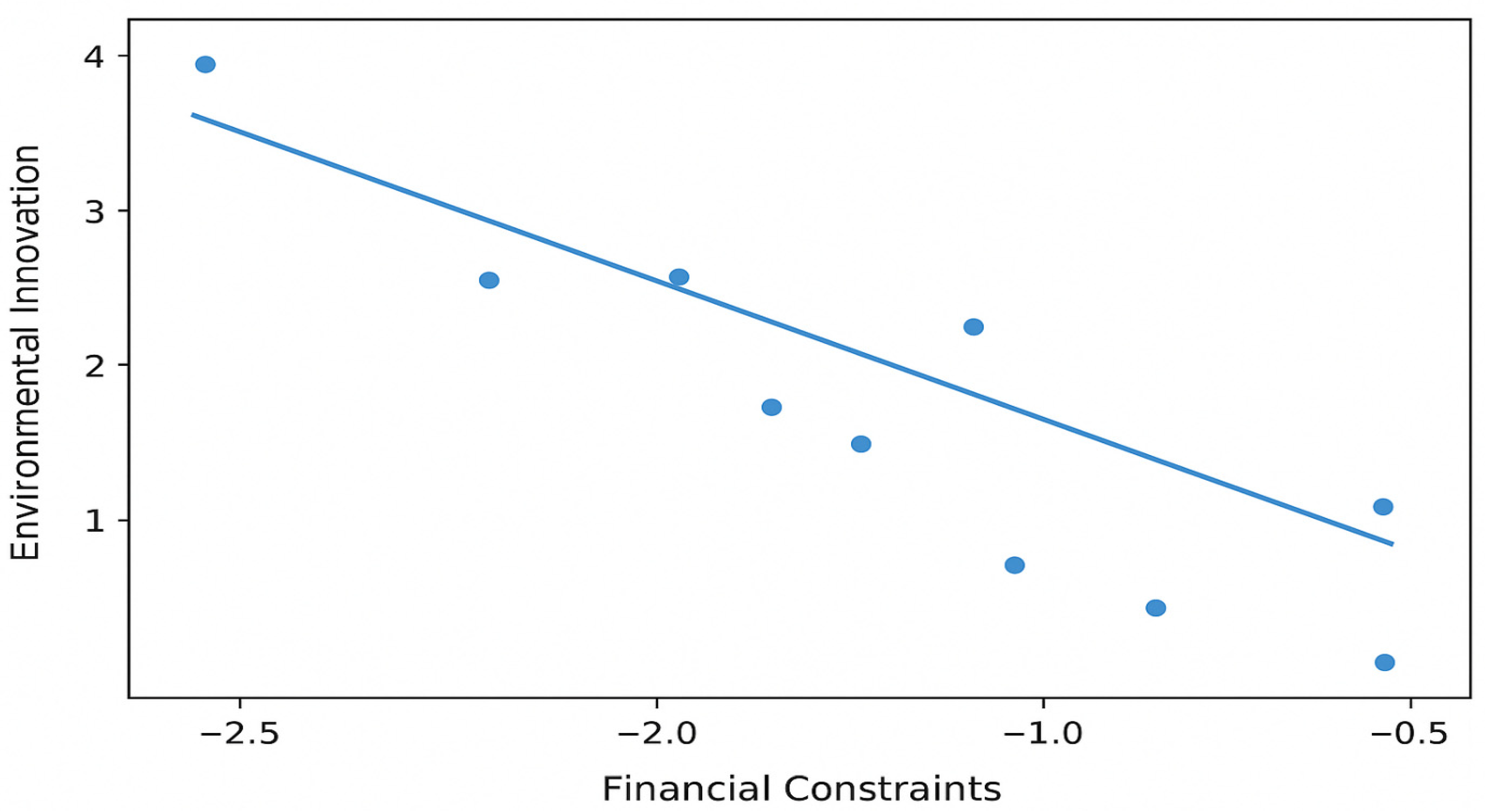

Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of financial constraints on environmental innovation. The horizontal axis (x) shows financial constraints, while the vertical axis (y) shows Environmental Innovation (predicted value/standardized). The downward-sloping line depicts the predicted level of environmental innovation at different levels of financial constraint. Each point represents the firm-level average of financial constraints (FC) and environmental innovation (EI) over the 2012–2024 sample period. The solid line shows the fitted regression line from Model (1), illustrating the negative relationship between FC and EI after controlling for firm size, age, R&D intensity, and industry. This indicates that, holding controls constant, a one-standard-deviation increase in financial constraints is associated with a ~0.37 standard-deviation decrease in environmental innovation. Firms facing greater liquidity shortages, higher leverage, or lower interest-coverage scores allocate fewer resources to green R&D, green patents, and other EI activities. The Figure confirms H1: financial constraints hinder environmental innovation. The slope’s steepness indicates the strength of this inhibitory effect. In our sample, the effect is moderate-to-large (β = −0.37), suggesting financing barriers are a meaningful impediment to eco-innovation for many firms.

An auxiliary reverse-causality check, in which financial constraints are regressed on lagged business sustainability and competitive advantage within a dynamic GMM framework, yields a small, statistically insignificant coefficient for lagged BS/CA. At the same time, our core FC → EI estimates remain robust. This suggests that reverse causality is unlikely to be the primary driver of the observed relationships.

Table 5 shows the moderating influences of management quality and institutional pressures. Model 4 indicates that management quality substantially moderates the association between financial constraints and environmental innovation (interaction β = 0.127,

p < 0.01). The positive coefficient signifies that superior management quality mitigates the adverse effects of budgetary restrictions, hence corroborating H3.

Table 5 presents the moderating effects of management quality and institutional pressures. Model 5 demonstrated that institutional pressures mitigate this connection (interaction β = 0.118,

p < 0.01). Firms operating in strong regulatory and normative environments experience a reduced negative influence of financial constraints on environmental innovation, confirming H4. Interaction plots show that enterprises with superior managerial quality or robust institutional contexts sustain elevated levels of environmental innovation, even under significant financial constraints.

Figure 3 presents the moderation analysis. The horizontal axis (x) represents financial Constraints (standardized), and the vertical axis (y) is the predicted environmental innovation. The two plotted lines represent low management quality and high management quality. The space between the two lines shows how the relationship between financial constraints and EI differs by managerial capability. Analyzing the Figure, it is clear that the interaction term FC × MQ was positive and significant (interaction β ≈ +0.127,

p < 0.01). This positive interaction indicates that management quality weakens the adverse effect of financial constraints on environmental innovation.

Figure 3 illustrates that the negative slope between financial constraints and environmental innovation is substantially steeper for firms with low management quality than for those with high management quality, confirming H3.

Taken together, the two moderating models suggest a consistent pattern. When management quality is high, the negative relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation becomes weaker, indicating that capable management teams can partially neutralize the adverse impact of tight financing on eco-innovation. Similarly, when institutional pressures are intense, the adverse effects of financial constraints are attenuated, suggesting that demanding regulatory and normative environments encourage firms to maintain eco-innovative activity even under financial stress. Jointly considering H3 and H4, the findings indicate that firms facing both high management quality and intense institutional pressures are in a particularly advantageous position: the constraint–innovation trade-off is softened from both the internal (capability) and external (legitimacy) sides, making financial constraints less detrimental for environmental innovation than in firms with weak management and/or weak institutional pressures.

Subsample estimations provide further nuance regarding contextual adaptability. In high-emission, capital-intensive industries, the moderating effect of institutional pressures on the FC–EI relationship is noticeably firmer, consistent with the idea that stricter regulation and stakeholder scrutiny make eco-innovation more salient. In contrast, the moderating role of management quality is comparatively more pronounced in less stringent institutional environments, where internal capabilities substitute for weaker external pressures. Across developed and emerging economies, the direction of the moderating effects remains the same, but their magnitude is larger in countries with relatively strong environmental and governance frameworks. These patterns underscore that the moderating mechanisms identified in H3 and H4 are context-sensitive, even though the core relationships are robust across subgroups.

To synthesize the empirical results,

Table 6 provides an overview of the seven hypotheses (H1–H7), the main models used to test each, and the corresponding conclusions. Overall, the evidence supports all of the hypothesized relationships, with H5 indicating partial mediation.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of financial constraints on environmental innovation and the resultant effect of environmental innovation on business sustainability and competitive advantage. It further analyzed how management quality and institutional pressures affect the relationship between financial constraints and environmental innovation. Furthermore, the positive direct effects of management quality and institutional pressures on environmental innovation confirm H6 and H7. This means that, even beyond their moderating roles, internal leadership quality and external legitimacy pressures independently foster higher levels of environmental innovation.

The results provide strong empirical support for the suggested framework. Financial constraints negatively affected environmental innovation, while environmental innovation positively and significantly contributed to company sustainability and competitive advantage. Additionally, both the quality of management and institutional pressures were identified as factors that mitigate the adverse association between financial constraints and environmental innovation. Environmental innovation mediated the link between financial constraints and business sustainability.

Moreover, the discovery that financial constraints negatively affect environmental innovation aligns with several previous studies emphasizing the dependence of innovation initiatives on resources [

12,

14,

20]. Companies with financial constraints or restricted access to external financing frequently diminish their investment in research and development, especially in high-cost, high-uncertainty environmental projects. Similar connections have been recognized in EU manufacturing SMEs and Asian markets, where financial constraints hindered eco-innovation initiatives [

2,

3,

4].

Moreover, the positive correlation between environmental innovation and economic sustainability corresponds with the “Porter Hypothesis,” which asserts that innovation-driven environmental solutions may improve both environmental performance and profitability. The study’s findings validate that companies involved in environmental innovation experience improved efficiency, increased stakeholder legitimacy, and superior market performance, supporting the conclusions of some authors [

18,

19].

The moderating roles of management quality and institutional pressures align with prior findings, suggesting that both internal and external facilitators can mitigate the negative impacts of financial constraints on innovation. Research indicates that management quality, strong governance, and regulatory enforcement are crucial in addressing resource shortage [

1,

25]. The results indicate that organizations with superior management teams continue to invest in environmental innovation, even when faced with financial constraints. Likewise, companies located in strong institutional environments are either compelled or supported to innovate despite resource constraints, consistent with the institutional theory perspective [

28].

This study differs from previous research in notable aspects; however, most conclusions are consistent with current data. While some previous studies suggested that financial constraints completely hinder innovation activity [

2,

6], the current study reveals only a partial negative correlation, suggesting that not all financially constrained enterprises experience the same level of difficulty. The findings indicate that companies with superior management quality or operating within strong institutional frameworks persist in their innovation endeavors. These findings challenge deterministic assumptions in previous research that financial constraints inevitably hinder environmental innovation.

This study reveals a partial mediating effect of environmental innovation on the relationship between financial constraints and corporate sustainability. Previous research has frequently shown that financial constraints directly diminish both creativity and organization [

12,

16,

19]. This study illustrates that environmental innovation serves as a resilience mechanism, enabling enterprises to maintain competitiveness despite constrained financial resources. This improves the understanding of the constraint–innovation–performance relationship.

The study’s cross-country findings indicate that institutional pressures have varying impacts based on regulatory maturity and cultural expectations. Companies in nations with strict environmental legislation or strong sustainability standards have developed more significant solutions to constraints than those in less established institutional environments. These comparative findings surpass individual-nation research and illustrate the contextual dependence of institutional pressures. This research presents numerous original contributions to the literature on sustainable company strategy and innovation under constraints. The study integrates Institutional Theory, Resource-Based View (RBV), and Stakeholder Theory to develop a comprehensive model that clarifies the impact of internal and external factors on innovation outcomes under financial constraints. This integration transcends singular perspectives that focus solely on financial or institutional pressures in isolation. The study empirically demonstrates that environmental innovation mediates the relationship between financial constraints and business sustainability, offering a new perspective on how companies transform financial constraints into lasting competitive advantages.

This research illustrates that management quality (internal competence) and institutional pressures (external legitimacy mechanisms) work synergistically to alleviate the negative impacts of financial constraints, in contrast to prior studies that analyzed these factors in isolation. Utilizing data from companies in both developed and developing countries improves generalizability and reveals contextual subtleties that are often neglected in previous single-market research. The discovery that specific financially constrained organizations maintain innovative performance through strategic and institutional adaptation provides additional evidence of resilient innovation pathways, a term increasingly recognized in modern sustainability studies.

From an Institutional Theory perspective, this research demonstrates that coercive and normative pressures significantly influence the advancement of environmental innovation, particularly in the context of financial constraints faced by organizations. Companies facing strict legislation, stakeholder oversight, or social demands are less likely to forgo sustainable practices. This study confirms that institutional pressures influence compliance and innovative behaviors motivated by the quest for legitimacy. It illustrates how the institutional environment may mitigate internal financial deficiencies by offering external motivation, support systems, or reputational incentives.

Within the RBV framework, the moderating effect of management quality reinforces the claim that internal capabilities determine a firm’s capacity to reallocate resources and sustain innovation under constraints. Effective management teams possess dynamic qualities that enable resource recombination and strategy adaptation, which are essential for fostering environmental innovation under constrained financial resources. This finding corroborates the Resource-Based View (RBV) assertion that variations in capabilities account for performance disparities among enterprises in similar external conditions.

In accordance with Stakeholder Theory, the finding that environmental innovation improves business sustainability and competitive advantage highlights the strategic importance of fulfilling stakeholder expectations. Companies that actively meet the expectations of investors, consumers, and regulators achieve increased market legitimacy, superior brand recognition, and sustained resilience. Thus, environmental innovation serves as a bridge between financial constraints and business sustainability by strengthening stakeholder relationships and trust.

The integration of different theoretical views indicates that the relationship between financial constraints and competitive advantage is neither linear nor predictable. The implementation of environmental innovation as a mediating mechanism depends on internal strategic capabilities (Resource-Based View) and external institutional legitimacy (Institutional Theory). Stakeholder Theory enhances this theory by elucidating the rationale behind organizations’ pursuit of innovation, legitimacy, and performance outcomes. This study conclusively shows that financial constraints do not necessarily lead to a decline in creativity. In contrast, companies with proficient management and situated in favorable institutional environments can turn constraints into opportunities for sustainable innovation and competitive advantage.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the influence of financial constraints on environmental innovation and the subsequent effect of environmental innovation on business sustainability and competitive advantage. The study examined the moderating influences of management quality and institutional pressures on this connection. The study, utilizing data from 280 enterprises across various industries and countries from 2012 to 2024, presents persuasive evidence that companies may convert financial constraints into strategic opportunities through environmental innovation.

The findings indicate that financial constraints have a considerable negative impact on environmental innovation, affirming that insufficient liquidity and limited access to funding are substantial obstacles to sustainability-oriented innovation. The study reveals that environmental innovation significantly and favorably affects business sustainability and competitive advantage, supporting the assertion that sustainability programs can deliver both environmental and economic benefits.

The study indicates that the negative impact of financial constraints on environmental innovation is alleviated by exceptional management quality and intense institutional pressures. Companies led by proficient management teams and operating under supportive institutional frameworks are better able to sustain innovation in the face of financial constraints. Furthermore, environmental innovation partially mediates the relationship between financial constraints and business sustainability, indicating that innovation serves as a strategic tool that enables businesses to convert limited resources into enduring competitive advantages.

The study’s findings provide novel insights into the scholarly discussion on sustainability, innovation, and strategic management. They challenge the notion that financial constraints automatically impede innovation by showing that organizations can maintain creative performance through internal capabilities and external legitimacy mechanisms. This result integrates and elaborates on Institutional Theory, Resource-Based View (RBV), and Stakeholder Theory, illustrating that the interaction between internal resources and external pressures influences organizations’ ability to innovate for sustainability.

Theoretically, this research improves our understanding of how financial constraints do not function in isolation but dynamically interact with organizational and institutional circumstances. The findings highlight the importance of management quality, governance standards, and legislative support in enabling institutions to pursue environmental innovation amid financial constraints.

This research establishes that environmental innovation functions as both a mitigator, alleviating the negative impacts of financial constraints, and a connector, linking financial resilience to sustainable competitiveness. The study asserts that viewing financial constraints as opportunities for creativity and adaptive innovation provides an optimistic outlook: organizations that prioritize environmental innovation, cultivate effective leadership, and operate within supportive institutional frameworks can attain sustainable success despite resource constraints.

7. Implications

This study significantly enhances the theoretical understanding of how organizations manage the conflict between financial constraints and environmental innovation to achieve sustainability and competitive advantage. This research enhances a comprehensive model of sustainable strategic conduct under constraints by combining the Resource-Based View (RBV), Institutional Theory, and Stakeholder Theory.

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study integrated Institutional Theory, RBV, and Stakeholder Theory into a unified framework explaining how internal capabilities and external legitimacy pressures jointly shape eco-innovation under financial constraints. The study conceptualized environmental innovation as a resilience mechanism that partially mediates the link between financial constraints and sustainability-oriented competitive advantage. The study showed that management quality and institutional pressures work as complementary moderators, demonstrating that constraints do not mechanically suppress innovation when firms possess strong capabilities and operate in demanding institutional environments.

7.2. Managerial Implications

Managers should treat environmental innovation as a strategic investment that can unlock both sustainability and financial benefits, even under tight budgets. Strengthening management quality, such as governance, leadership skills, and strategic flexibility, may help maintain eco-innovation activities despite financing frictions. Equally, firms can leverage institutional pressures and stakeholder expectations to justify and support green investments internally, positioning constraints as catalysts for efficiency and creativity.

7.3. Policy Implications

Policymakers can reduce the negative impact of financial constraints on eco-innovation by expanding green finance instruments, subsidies, and tax incentives. The study shows that stronger and predictable environmental regulations, combined with robust governance frameworks, encourage firms to innovate rather than delay ecological investments during financially challenging periods. It can be deduced that targeted programs for capital-intensive and high-emission industries, and support for firms in emerging economies, can enhance the diffusion of environmental innovation where constraints are most binding.

8. Limitations and Future Research

First, the sample is restricted to publicly listed firms in six countries, which may limit generalizability to privately held firms or other regions.

Second, although we combine multiple indicators for financial constraints and environmental innovation, both constructs remain proxy-based and may not fully capture all dimensions of financing frictions or eco-innovation.

Third, while dynamic panel GMM helps mitigate endogeneity, unobserved factors and residual reverse causality cannot be completely ruled out. Fourth, industry and country heterogeneity are only partially addressed through dummies; more extensive multilevel modeling would provide deeper insight into sector- and context-specific dynamics.

Fourth, although we rely on widely used proxies (such as leverage ratio for financial constraints, patents, and ESG innovation scores for environmental innovation), our measures inevitably capture only specific dimensions of the underlying constructs. For example, we do not observe non-performing loans for all firms, nor do we entirely separate product and process eco-innovations across the entire sample period. Future research could benefit from richer, more granular indicators of financial distress and environmental innovation, such as bank-level credit data and detailed patent classifications, to further validate and extend our findings.

Fifth, although we conceptualize management quality and institutional pressures as complementary moderators, our empirical models estimate their moderating effects in separate specifications rather than via a formal MQ × IP or three-way interaction term. We do so intentionally to avoid over-parameterization and multicollinearity in a moderately sized panel. Future research could build on our framework by estimating full interaction structures and multilevel models to unpack the interplay between internal capabilities, institutional context, and environmental innovation.

Future research could extend the analysis to small- and medium-sized enterprises, incorporate richer measures of financial distress (such as non-performing loans and default probabilities), distinguish more finely between product, process, and organizational eco-innovations, and employ case-based or mixed-method designs to understand managerial decision-making processes under financial constraints better.