Life-Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment: Enhancing Sustainability Through Process Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Review Approach

2.2. Literature Retrieval and Screening

- First screening: Titles and abstracts were examined to make sure they were pertinent to environmental impact indicators and technical treatment performance. As a result, the selection was narrowed down to 142 publications, most of which were critical reviews and peer-reviewed research studies written in both French and English.

- Eligibility evaluation: To guarantee that LCA assumptions were transparent, full-text versions were reviewed. Excluded were studies that only examined degradation at the laboratory scale without system-level evaluation or that lacked clearly defined functional units and system boundaries.

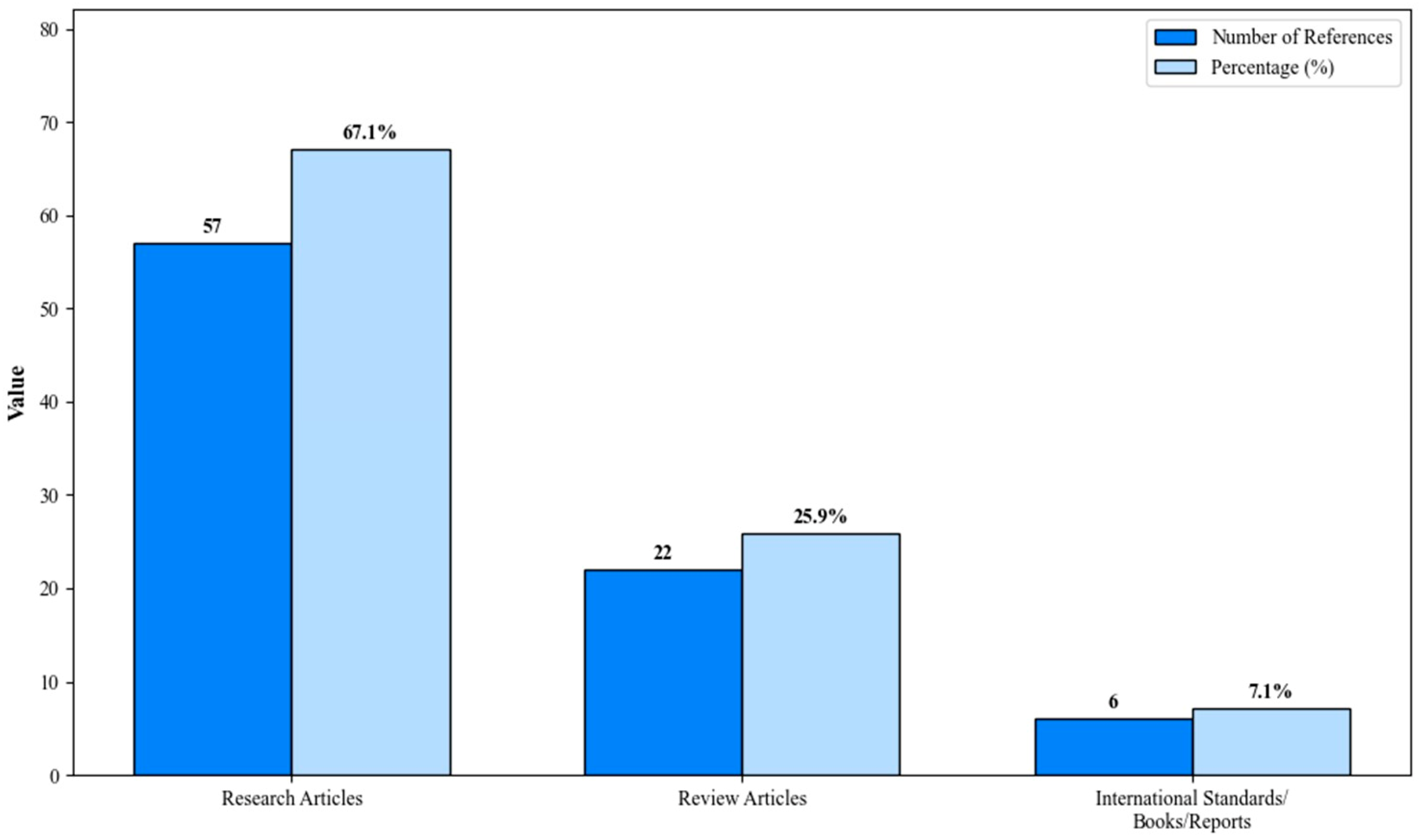

- Final inclusion: In the end, 85 studies were chosen for a thorough examination. Figure 2 shows the distribution of these publications by kind, including research articles, review articles, and international standards.

3. Sources and Importance of Wastewater Treatment

4. Bulk Organic Pollutants

4.1. Organic Pollutants in Industrial Wastewater

4.2. Organic and Emerging Pollutants in Domestic Wastewater

4.3. Nutrients and Pesticide Residues from Agricultural Runoff

5. Impacts of Wastewater Contamination on Public Health and the Environment

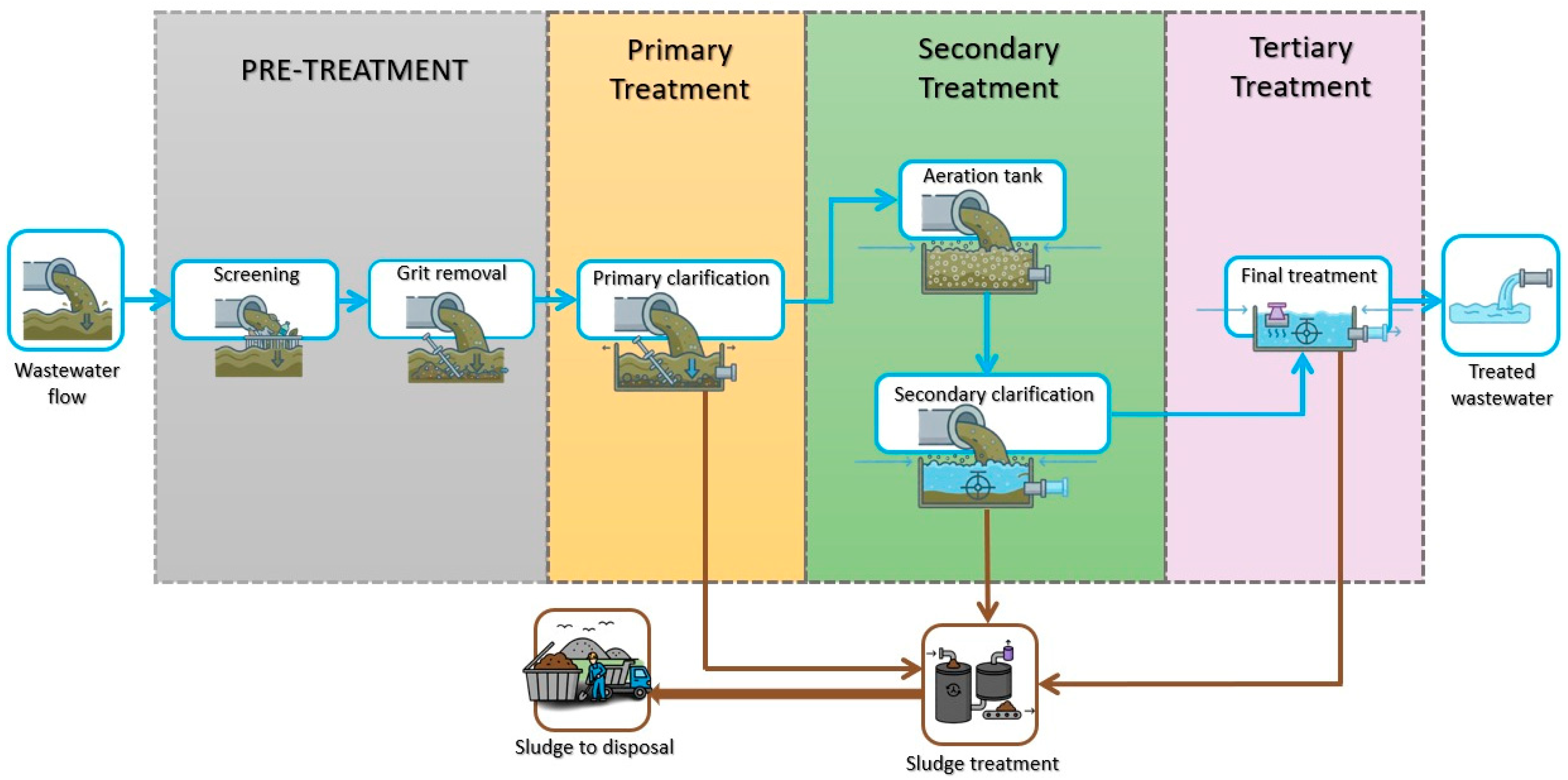

6. Key Stages of Wastewater Treatment

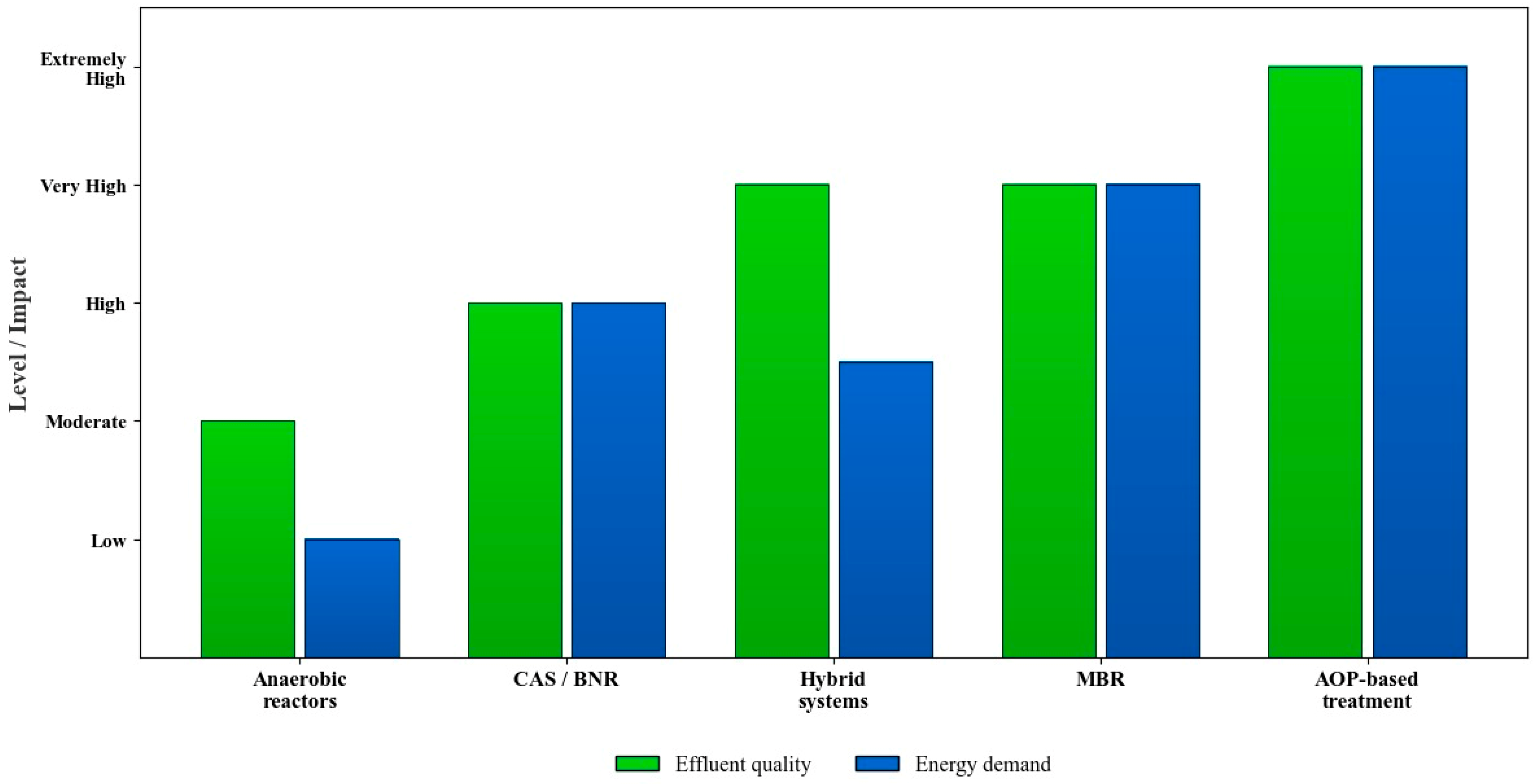

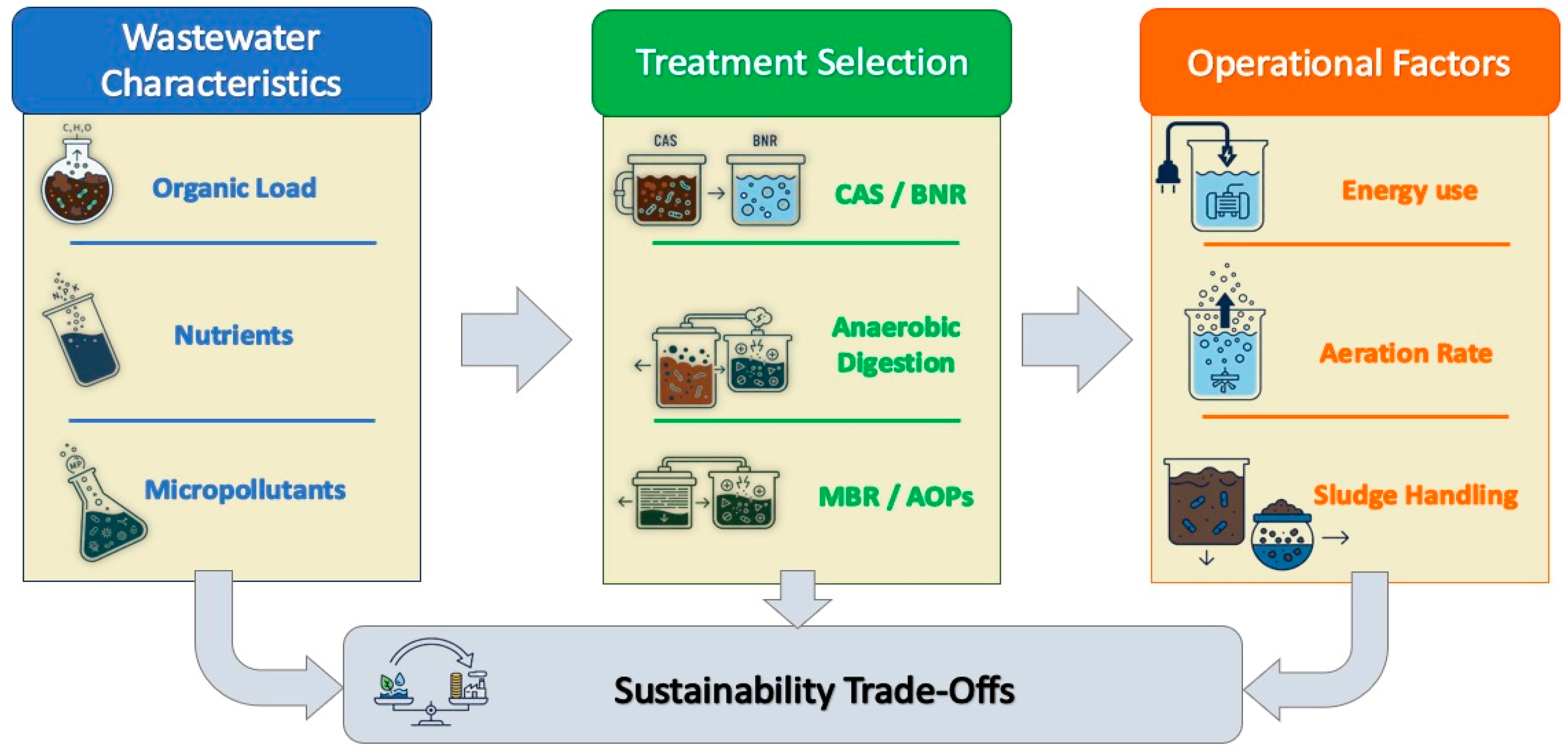

7. Techniques Used for Wastewater Treatment

8. Sludge Treatment and Disposal

9. Sectoral Applications of Treated Wastewater Reuse (TWR): A Comparative LCA Perspective

10. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Wastewater Treatment

Definition and Purpose of LCA

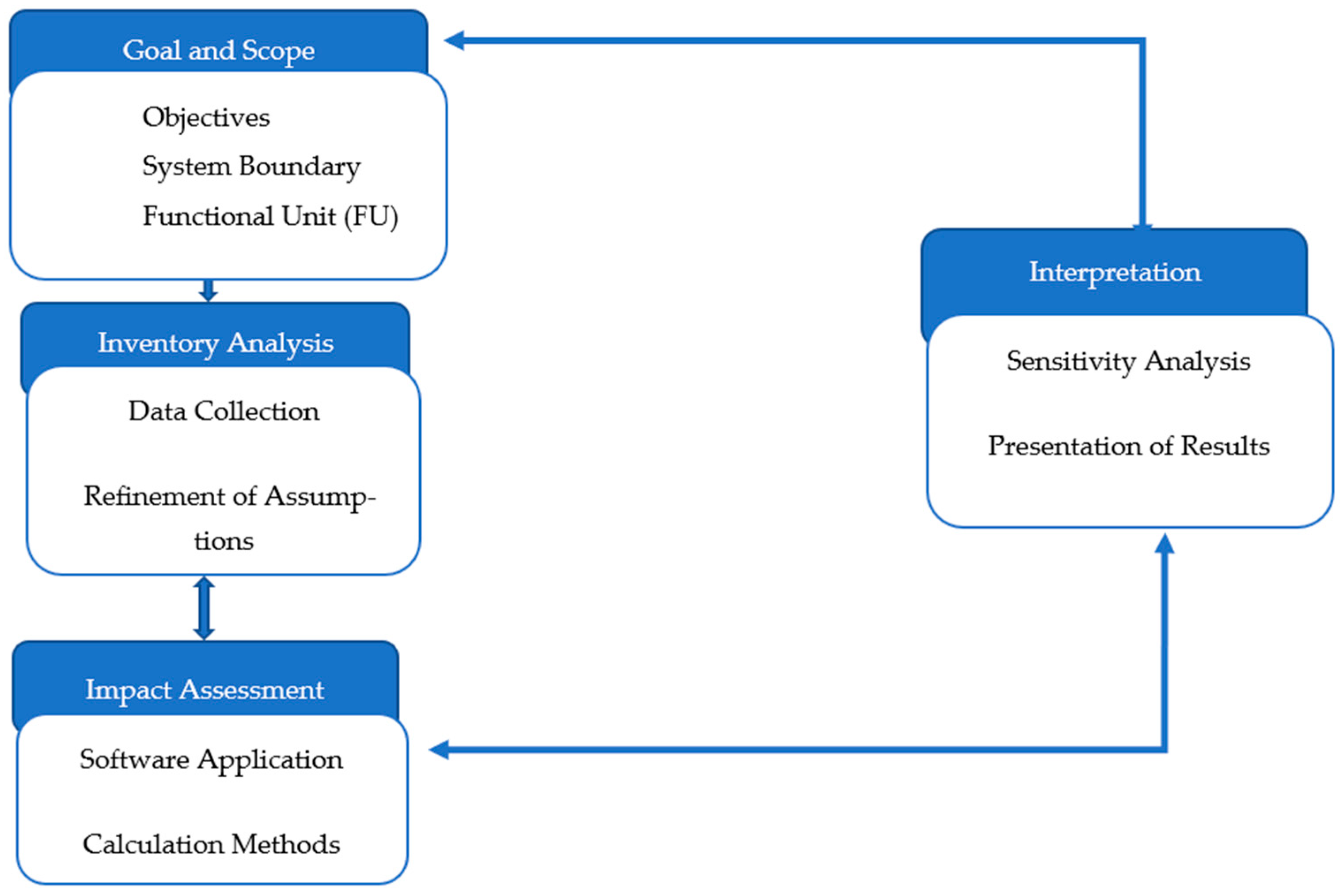

11. Key Steps in LCA

11.1. Goal and Scope Definition

11.1.1. Functional Unit (FU)

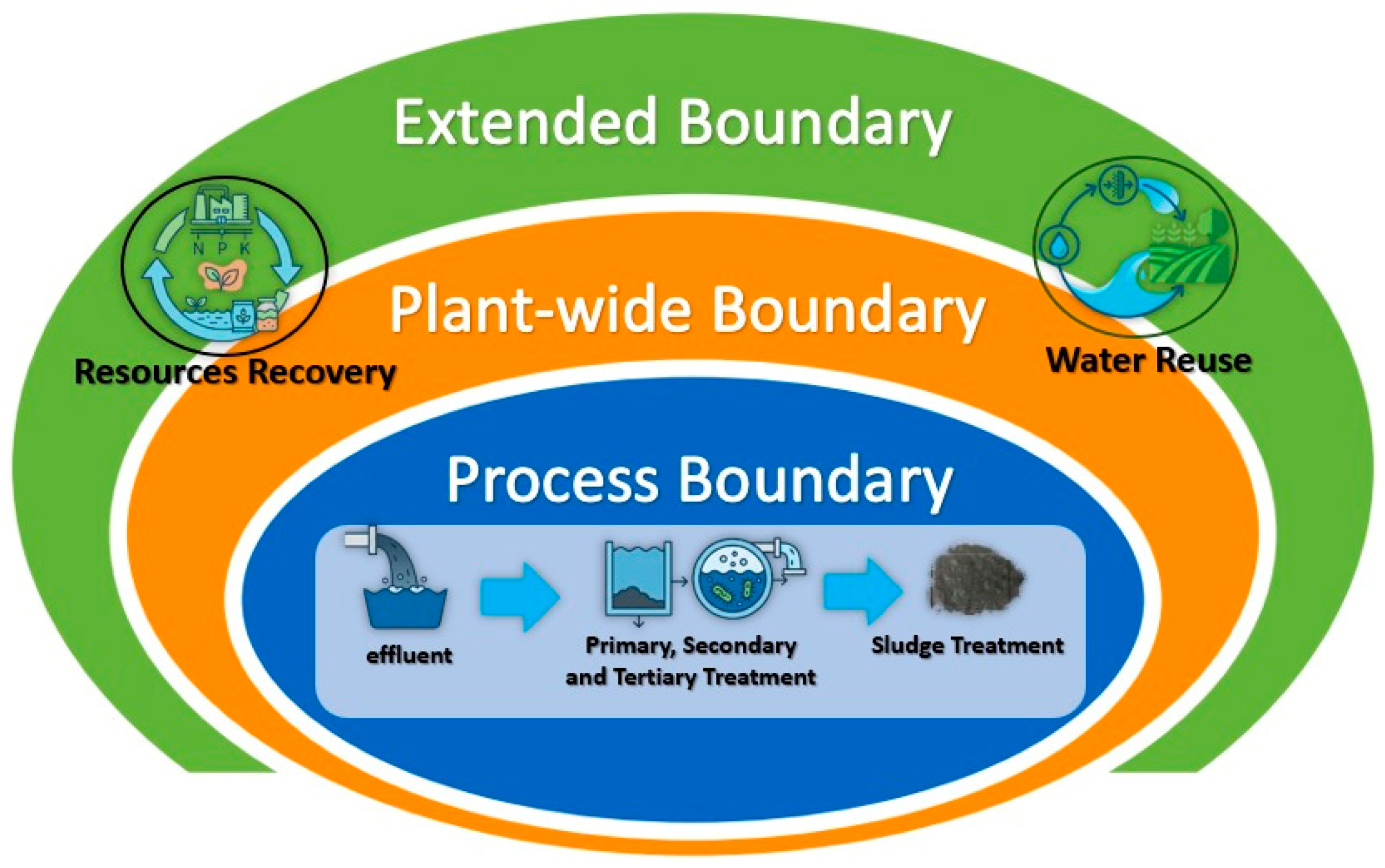

11.1.2. System Boundaries and Scope Assumptions

11.1.3. Allocation and Treatment of Co-Products

11.1.4. Inclusion of Direct Greenhouse Gas Emissions (N2O and CH4)

11.1.5. Sludge Management and Recovery Pathways in Wastewater LCA Studies

11.2. Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI)

11.3. Life-Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

11.4. Interpretation of Results

12. Main Environmental Indicators Used in LCA

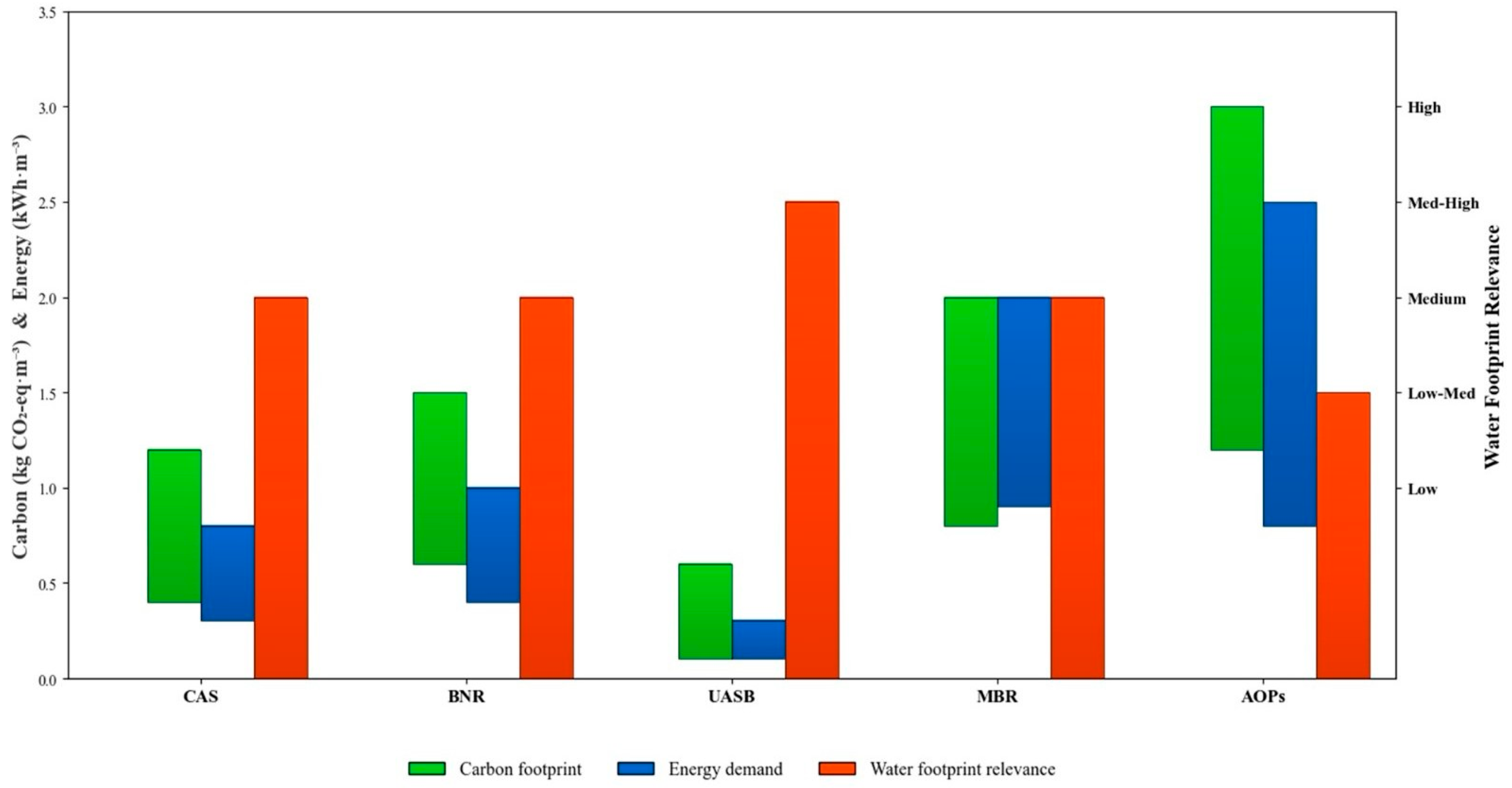

12.1. Footprints as Environmental Indicators

12.2. Carbon Footprint

12.3. Water Footprint

- The Blue Water Footprint (BWF) measures the consumption of surface and groundwater.

- The Green Water Footprint (GrWF) accounts for the use of rainwater stored in soil.

12.4. Energy Balance

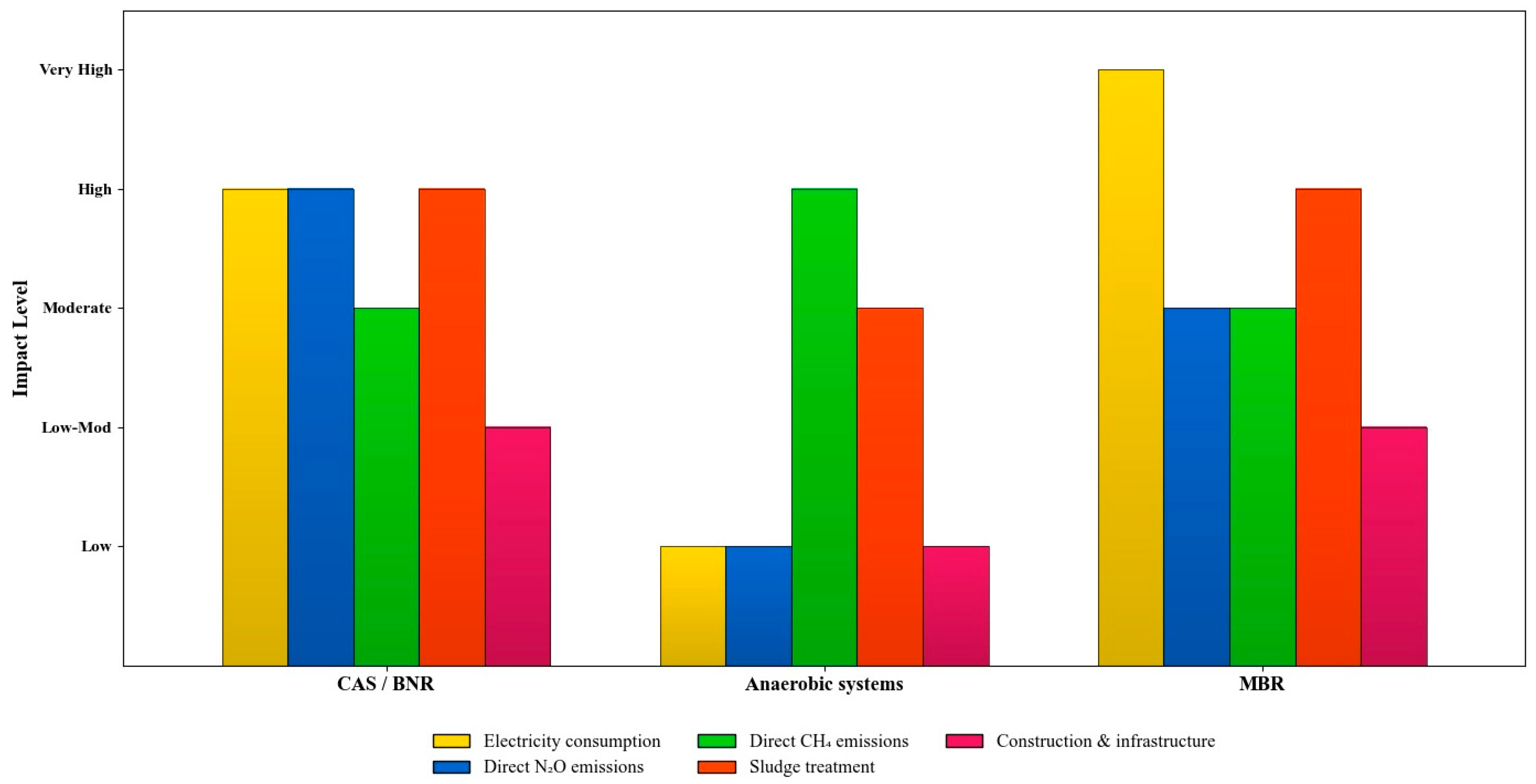

13. Integrated Comparison of Environmental Indicators Across Wastewater Treatment Systems

14. Synthesis of LCA Results for Wastewater Treatment Systems

15. Environmental IMPACT Assessment Methods

- Resource-based methods concentrate on the depletion of natural resources (inputs), often using indicators such as Cumulative Energy Demand (CED).

- Emission-based methods evaluate the environmental burden of emissions (outputs) through detailed impact models.

- CML: This method emphasizes midpoint impact categories and includes both core and optional categories.

- IMPACT 2002+: Building upon CML 2002 and Eco-indicator 99, this method links 14 midpoint categories to four endpoint (damage) categories.

- ReCiPe: A successor to CML 2002 and Eco-indicator 99, ReCiPe harmonizes midpoint and endpoint modeling into an integrated framework, facilitating both detailed and aggregated environmental assessments [72].

16. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Current Limitations of LCA in Wastewater Treatment

17. Future Perspectives

18. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhakar, V.; Sihag, N.; Gieschen, R.; Andrew, S.; Herrmann, C.; Sangwan, K.S. Environmental Impact Analysis of a Water Supply System: Study of an Indian University Campus. Procedia CIRP 2015, 29, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Raad, A.A.; Hanafiah, M.M. Removal of Inorganic Pollutants Using Electrocoagulation Technology: A Review of Emerging Applications and Mechanisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Li, S.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Jiang, H. Environmental Impacts of Resource Recovery from Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2019, 160, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, A.; Simi, S.; Pulvirenti, I.; Valese, A. Cradle-to-Grave LCA of In-Person Conferences: Hotspots, Trade-Offs and Mitigation Pathways. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, I.; Gómez, M.J.; Molina-Díaz, A.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Fernández-Alba, A.R.; García-Calvo, E. Ranking Potential Impacts of Priority and Emerging Pollutants in Urban Wastewater through Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Chemosphere 2008, 74, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Rosal, R.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Life Cycle Assessment of Urban Wastewater Reuse with Ozonation as Tertiary Treatment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2009, 407, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høibye, L.; Clauson-Kaas, J.; Wenzel, H.; Larsen, H.F.; Jacobsen, B.N.; Dalgaard, O. Sustainability Assessment of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Technologies. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, H.; Larsen, H.F.; Clauson-Kaas, J.; Høibye, L.; Jacobsen, B.N. Weighing Environmental Advantages and Disadvantages of Advanced Wastewater Treatment of Micro-Pollutants Using Environmental Life Cycle Assessment. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 57, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, V.U.; Omokpariola, D.O.; Onwukeme, V.I.; Nweke, E.N.; Omokpariola, P.L. Pollution Investigation and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil and Water from Selected Dumpsite Locations in Rivers and Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Environ. Anal. Health Toxicol. 2021, 36, e2021023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berradi, M.; Hsissou, R.; Khudhair, M.; Assouag, M.; Cherkaoui, O.; El Bachiri, A.; El Harfi, A. Textile Finishing Dyes and Their Impact on Aquatic Environs. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng-Peprah, M.; Acheampong, M.A.; deVries, N.K. Greywater Characteristics, Treatment Systems, Reuse Strategies and User Perception—A Review. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tušer, I.; Oulehlová, A. Risk Assessment and Sustainability of Wastewater Treatment Plant Operation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.-P.; Zong, Z.-Q.; Qiao, J.-C.; Li, Z.-Y.; Hu, C.-Y. Exposure to Pesticides and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.D.; Weed, D.L.; Mink, P.J.; Mitchell, M.E. A Weight-of-Evidence Review of Colorectal Cancer in Pesticide Applicators: The Agricultural Health Study and Other Epidemiologic Studies. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2012, 85, 715–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakkan-Mambir, B.; Deloumeaux, J.; Luce, D. Geographical Variations of Cancer Incidence in Guadeloupe, French West Indies. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Nuzhat, S.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Rafa, N.; Uddin, A.; Inayat, A.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Ong, H.C.; Chia, W.Y.; et al. Recent Developments in Physical, Biological, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Techniques for Removing Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Thomas, S.M.; Bodour, A.A. Prioritizing Research for Trace Pollutants and Emerging Contaminants in the Freshwater Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3462–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolong, N.; Ismail, A.F.; Salim, M.R.; Matsuura, T. A Review of the Effects of Emerging Contaminants in Wastewater and Options for Their Removal. Desalination 2009, 239, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.; De Souza, A.O.; Bernardes, M.F.F.; Pazin, M.; Tasso, M.J.; Pereira, P.H.; Dorta, D.J. A Perspective on the Potential Risks of Emerging Contaminants to Human and Environmental Health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 13800–13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Show, P.-L. A Review on Effective Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Aquatic Systems: Current Trends and Scope for Further Research. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, P. Towards Energy Positive Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasulochana, P.; Preethy, V. Comparison on Efficiency of Various Techniques in Treatment of Waste and Sewage Water—A Comprehensive Review. Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2016, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Haider, W. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis and Its Potential Applications in Water and Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 342001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzkiewicz, M.; Polska-Adach, E.; Hubicki, Z. Application of Titania Based Adsorbent for Removal of Acid, Reactive and Direct Dyes from Textile Effluents. Adsorption 2019, 25, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.H.; Tan, H.K.; Lau, S.Y.; Yap, P.-S.; Danquah, M.K. Potential and Challenges of Enzyme Incorporated Nanotechnology in Dye Wastewater Treatment: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, N.; Aziz, F.; Jamaludin, N.A.; Mutalib, M.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Salleh, W.N.W.; Jaafar, J.; Yusof, N.; Ludin, N.A. A Review of Integrated Photocatalyst Adsorbents for Wastewater Treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7411–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.; De Haas, D.; Hartley, K.; Lant, P. Comprehensive Life Cycle Inventories of Alternative Wastewater Treatment Systems. Water Res. 2010, 44, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, L.; Foley, J.; Guest, J.S.; Hospido, A.; Larsen, H.F.; Morera, S.; Shaw, A. Life Cycle Assessment Applied to Wastewater Treatment: State of the Art. Water Res. 2013, 47, 5480–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, G.; Molinos-Senante, M.; Hospido, A.; Hernández-Sancho, F.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Environmental and Economic Profile of Six Typologies of Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2011, 45, 5997–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wong, M. Carbon Footprint Analyses of Mainstream Wastewater Treatment Technologies under Different Sludge Treatment Scenarios in China. Water 2015, 7, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, M.; Horst, T.; Quicker, P. Thermal Treatment of Sewage Sludge in Germany: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 263, 110367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, K.K.; Soni, R.; Jamal, Q.M.S.; Tripathi, P.; Lal, J.A.; Jha, N.K.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, V.; Ruokolainen, J. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse: A Review of Its Applications and Health Implications. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, A.; Yusuf, M.; Qadir, A.; Ezaier, Y.; Vambol, V.; Ijaz Khan, M.; Ben Moussa, S.; Kamyab, H.; Sehgal, S.S.; Prakash, C.; et al. Wastewater Treatment: A Short Assessment on Available Techniques. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 76, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutarba, Y.; Benzaouak, A.; Ben Ali, M.; Nehhal, S.; Taouk, B.; El Hamidi, A.; Bellaouchou, A.; Abdelouahed, L. Valorization of Urban Biosolids for Sustainable Hydrogen Production through Steam Gasification over Silicon Oxide Sand. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 675, 01012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; An, C. A Review on Solid Waste Management in Canadian First Nations Communities: Policy, Practices, and Challenges. Clean. Waste Syst. 2023, 4, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghalari, Z.; Dahms, H.-U.; Sillanpää, M.; Sosa-Hernandez, J.E.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Effectiveness of Wastewater Treatment Systems in Removing Microbial Agents: A Systematic Review. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowska, D.; Bernat, K. Waste Willow-Bark from Salicylate Extraction Successfully Reused as an Amendment for Sewage Sludge Composting. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Baek, K. Selective Recovery of Ferrous Oxalate and Removal of Arsenic and Other Metals from Soil-Washing Wastewater Using a Reduction Reaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Aleem, M.; Fang, F.; Xue, Z.; Cao, J. Potentials and Challenges of Phosphorus Recovery as Vivianite from Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.H.; Juang, R.-S. Efficient Removal of Cationic Dyes from Water by a Combined Adsorption-Photocatalysis Process Using Platinum-Doped Titanate Nanomaterials. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 99, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO-14040; Environmental Management e Life Cycle Assessment e Principles and Framework: International Standard 14040. International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management e Life Cycle Assessment e Requirements and Guidelines. International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Godin, D.; Bouchard, C.; Vanrolleghem, P.A. Net Environmental Benefit: Introducing a New LCA Approach on Wastewater Treatment Systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.; Simon, M.; Burkitt, T. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Two Options for Small-Scale Wastewater Treatment: Comparing a Reedbed and an Aerated Biological Filter Using a Life Cycle Approach. Ecol. Eng. 2003, 20, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.P.; Urbano, L.; Brito, A.G.; Janknecht, P.; Salas, J.J.; Nogueira, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment Options for Small and Decentralized Communities. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasopoulos, N.; Memon, F.A.; Butler, D.; Murphy, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment Technologies Treating Petroleum Process Waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 367, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.; Raluy, R.G.; Serra, L. Life Cycle Assessment of Water Treatment Technologies: Wastewater and Water-Reuse in a Small Town. Desalination 2007, 204, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, C.; Jekel, M. Sustainable Wastewater Management: Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Source-Separating Urban Sanitation Systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.S.; Harun, S.N.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Razman, K.K.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Tholibon, D.A. Life Cycle Assessment and Its Application in Wastewater Treatment: A Brief Overview. Processes 2023, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed Mohamed Mahgoub, M.; Van Der Steen, N.P.; Abu-Zeid, K.; Vairavamoorthy, K. Towards Sustainability in Urban Water: A Life Cycle Analysis of the Urban Water System of Alexandria City, Egypt. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, W. Towards More Accurate Life Cycle Assessment of Biological Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbar, P.P.; Karmakar, S.; Asolekar, S.R. Assessment of Wastewater Treatment Technologies: Life Cycle Approach. Water Environ. J. 2013, 27, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualino, J.C.; Meneses, M.; Abella, M.; Castells, F. LCA as a Decision Support Tool for the Environmental Improvement of the Operation of a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 3300–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Gutiérrez, R.A.; Giarola, S.; Bezzo, F. Optimal Design of Ethanol Supply Chains Considering Carbon Trading Effects and Multiple Technologies for Side-Product Exploitation. Environ. Technol. 2013, 34, 2189–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, R.K.; Bachmann, T.M.; Gold, L.S.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Jolliet, O.; Juraske, R.; Koehler, A.; Larsen, H.F.; MacLeod, M.; Margni, M.; et al. USEtox—The UNEP-SETAC Toxicity Model: Recommended Characterisation Factors for Human Toxicity and Freshwater Ecotoxicity in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Struijs, J.; Goedkoop, M.; Heijungs, R.; Jan Hendriks, A.; Van De Meent, D. Human Population Intake Fractions and Environmental Fate Factors of Toxic Pollutants in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Chemosphere 2005, 61, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodosiu, C.; Barjoveanu, G.; Sluser, B.R.; Popa, S.A.E.; Trofin, O. Environmental Assessment of Municipal Wastewater Discharges: A Comparative Study of Evaluation Methods. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Heijungs, R.; De Snoo, G.R. Theoretical Exploration for the Combination of the Ecological, Energy, Carbon, and Water Footprints: Overview of a Footprint Family. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 36, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, T.; Minx, J. A Definition of ‘Carbon Footprint’; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L.A.; Kemp, S.; Williams, I. ‘Carbon Footprinting’: Towards a Universally Accepted Definition. Carbon Manag. 2011, 2, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera-Guardia, A.; Bosch, L.; Corominas, L.; Pijuan, M. Nitrous Oxide and Methane Emissions from a Plug-Flow Full-Scale Bioreactor and Assessment of Its Carbon Footprint. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Chapagain, A.K. A.Y. Hoekstra, 2008. Water Neutral: Reducing and Offsetting the Impacts of Water Footprints. Water Resour. Manag. 2006, 21, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Farm Animals and Animal Products. Volume 2: Appendices; UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klemeš, J.J.; Varbanov, P.S.; Lam, H.L. Water Footprint, Water Recycling and Food-Industry Supply Chains. In Handbook of Waste Management and Co-Product Recovery in Food Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 134–168. ISBN 978-1-84569-391-6. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, A.; Wiedmann, T.; Ercin, E.; Knoblauch, D.; Ewing, B.; Giljum, S. Integrating Ecological, Carbon and Water Footprint into a “Footprint Family” of Indicators: Definition and Role in Tracking Human Pressure on the Planet. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 16, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuček, L.; Klemeš, J.J.; Kravanja, Z. A Review of Footprint Analysis Tools for Monitoring Impacts on Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 34, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; Van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A Harmonised Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, L.; Klemeš, J. The Environmental Performance Strategy Map: An Integrated LCA Approach to Support the Strategic Decision-Making Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeglehner, G.; Narodoslawsky, M. How Sustainable Are Biofuels? Answers and Further Questions Arising from an Ecological Footprint Perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3825–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeglehner, G.; Levy, J.K.; Neugebauer, G.C. Improving the Ecological Footprint of Nuclear Energy: A Risk-Based Lifecycle Assessment Approach for Critical Infrastructure Systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2005, 1, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Z.; Lin, Z.-S. Multiple Timescale Analysis and Factor Analysis of Energy Ecological Footprint Growth in China 1953–2006. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D. (Ed.) Sustainable Product Development: Tools, Methods and Examples; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-39148-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, M.Z.; Goedkoop, M.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; De Schryver, A.; Humbert, S.; Laurent, A.; et al. Identifying Best Existing Practice for Characterization Modeling in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plósz, B.G.; Benedetti, L.; Daigger, G.T.; Langford, K.H.; Larsen, H.F.; Monteith, H.; Ort, C.; Seth, R.; Steyer, J.-P.; Vanrolleghem, P.A. Modelling Micro-Pollutant Fate in Wastewater Collection and Treatment Systems: Status and Challenges. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, M.; Kreuzinger, N.; Strenn, B.; Gans, O.; Kroiss, H. The Solids Retention Time—A Suitable Design Parameter to Evaluate the Capacity of Wastewater Treatment Plants to Remove Micropollutants. Water Res. 2005, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muazu, R.I.; Rothman, R.; Maltby, L. Integrating Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Risk Assessment: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.C. Development of a Normalization Method for Social Life Cycle Assessment. Bachelor’s Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.T. Life Cycle Analysis in Wastewater: A Sustainability Perspective. In Waste Water Treatment and Reuse in the Mediterranean Region; Barceló, D., Petrovic, M., Eds.; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 14, pp. 125–154. ISBN 978-3-642-18280-8. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14042; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Life Cycle Impact Assessment. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Mayer, B.K.; Baker, L.A.; Boyer, T.H.; Drechsel, P.; Gifford, M.; Hanjra, M.A.; Parameswaran, P.; Stoltzfus, J.; Westerhoff, P.; Rittmann, B.E. Total Value of Phosphorus Recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6606–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, M.; Concepción, H.; Vrecko, D.; Vilanova, R. Life Cycle Assessment as an Environmental Evaluation Tool for Control Strategies in Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.D.; Parsons, S.A. Struvite Formation, Control and Recovery. Water Res. 2002, 36, 3925–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Benítez, A.; Vázquez, J.R.; Seco, A.; Serralta, J.; Rogalla, F.; Robles, A. Life Cycle Assessment of AnMBR Technology for Urban Wastewater Treatment: A Case Study Based on a Demo-Scale AnMBR System. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.L. Life Cycle Assessment of Nutrient Recycling from Wastewater: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.M.; Lohman, H.A.C.; Cook, S.M.; Peters, G.M.; Guest, J.S. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Urban Water Infrastructure: Emerging Approaches to Balance Objectives and Inform Comprehensive Decision-Making. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2017, 3, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pollutant Category | Representative Treatment Technologies | Energy Demand (kWh·m−3) | Sludge Generation | Climate Impact Relevance (GWP) | Key LCA-Related Trade-Offs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk organic matter (COD, BOD) | Conventional Activated Sludge (CAS), anaerobic reactors (UASB) | 0.3–0.8 (CAS); 0.1–0.3 (UASB) | High (CAS); Moderate (UASB) | Moderate–High (aeration, CH4/N2O) | Energy-intensive aeration vs. biogas recovery potential |

| Nutrients (N, P) | Biological Nutrient Removal (BNR), chemical precipitation | 0.4–1.0 | High | High (N2O emissions) | Trade-off between nutrient removal efficiency and GHG emissions |

| Heavy metals | Chemical precipitation, electrocoagulation, membrane filtration | 0.2–1.5 | High (metal-rich sludge) | Moderate | Hazardous sludge disposal and chemical consumption |

| Synthetic dyes and recalcitrant organics | Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), adsorption | 0.8–2.5 | Low–Moderate | High (electricity-driven) | High energy demand and potential toxic by-products |

| PPCPs and micropollutants | Ozonation, AOPs, Membrane Bioreactors (MBR) | 0.9–2.0 | Moderate | Moderate–High | Improved effluent quality vs. increased energy and material use |

| Pathogens | Disinfection, ultrafiltration, tertiary treatment | 0.1–0.6 | Low | Low–Moderate | Additional energy demand for polishing steps |

| Pollutant | Wastewater Context | Treatment Techniques | Efficiency | Typical Removal Efficiency | LCA Key Hotspots and Environmental Profile | Indicative Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAHs/BPA | Municipal/Industrial | AOPs, ozonation | High | PPCPs: 60–95% | Substantial energy profile. Major impact on Global Warming Potential (GWP) due to electricity use and ozone generation. | ~1.5–3.5 kg CO2 eq/m3 |

| Synthetic dyes | Industrial | Adsorption (activated carbon) | Moderate | Dyes: 60–90% | Adsorbent material generation. Environmental burden shifted to activated carbon production (embodied energy) and regeneration processes. | Extensive fossil resource depletion |

| Heavy metals | Industrial | Electrocoagulation | High | Metals: 80–99% | Electricity and electrode consumption, leading to mineral resource depletion and greenhouse gas emissions; metal-rich sludge generation. | ~0.5–2.0 kWh/m3 |

| Pharmaceuticals | Municipal/Industrial | Membrane filtration (MBR) | High | COD: >95%; PPCPs: 60–95% | High operational energy demand and membrane fouling; aeration for membrane cleaning is the dominant hotspot. Ecotoxicity decreased, but GWP increased. | ~0.8–2.5 kWh/m3 |

| Pathogenic microorganisms (E. coli, etc.) | Municipal/Industrial | Ultrafiltration, ozonation, UV irradiation | High | Pathogens: >99% | High energy demand, especially for ozonation and UV irradiation, increasing GWP. Ultrafiltration hotspots due to membrane manufacturing (embodied energy) and frequent backwashing/cleaning chemicals. | ~0.1–0.5 kWh/m3 (disinfection stage) |

| Treatment Method | Operating Conditions | Primary LCA Hotspot and Environmental Burden | Indicative Carbon Footprint (Kg CO2 eq/t DM) | Resource Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composting | 55–65 °C | Direct emissions: high CH4 and N2O during degradation | 150–300 | Nutrients (N, P) |

| Agricultural Reuse | Ambient | Toxicity: heavy metal and pathogen leaching in soil/underground water and transfer to food chain | Low (transport only) | High (especially in terms of enhancing soil fertility) |

| Anaerobic Digestion | k35–55 °C | Potential methane leakage: during storage | −50 to +100 (Net) | Energy (biogas) |

| Incineration | >850 °C | Air emissions: high toxic and pollutant gases (NOX, SOX, CO2, CO…); high consumption of fossil fuels for startup | 400–800 | Thermal energy |

| Pyrolysis | 400–800 °C | Input energy for heating; toxic compounds and residues in biochar (if not fully immobilized) | 100–400 | Bio-oil (energy, chemical synthesis); biochar |

| Gasification | 700–1000 °C, gasification agent (steam, O2 and/or CO2) | Requires high energy input (mainly fossil fuels); generation of tar, a subproduct characterized by its high-toxicity and its fouling effect on the reactors’ material | 100–300 | Very high and clean energy (mainly H2) |

| Landfilling | Ambient | Excessive use of land sources and important generation of CH4 due to anaerobic decay | 200–500 | None (negative) |

| Hydrothermal processes (HTC, HTL) | 180–370 °C, high pressure required | Necessitate high energy input; effluent toxicity | 200–500 | High-density fuels |

| Sector | Primary Reuse Pathway | Key LCA Benefit (Avoided Impact) | LCA Hotspot (Negative Impact) | Treatment Intensity (LCA Cost) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Irrigation (edible/non-edible) | Avoided synthetic fertilizer production (N, P) | Soil ecotoxicity from heavy metals/micropollutants | Low to medium (secondary + disinfection) |

| Industry | Cooling towers, boilers, scrubbing | Freshwater preservation in industrial clusters | High chemical footprint from scaling inhibitors | Medium to high (advanced membrane/AOP) |

| Environment | Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) | Salinity regulation; long-term aquifer security | Energy consumption for high-pressure injection | Medium (leverages natural SAT processes) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Laouane, H.; El Joumri, L.; Halhaly, A.; Arid, Y.; Labjar, N.; El Hajjaji, S. Life-Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment: Enhancing Sustainability Through Process Optimization. Sustainability 2026, 18, 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020605

Laouane H, El Joumri L, Halhaly A, Arid Y, Labjar N, El Hajjaji S. Life-Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment: Enhancing Sustainability Through Process Optimization. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020605

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaouane, Hajar, Loubna El Joumri, Amine Halhaly, Yassine Arid, Najoua Labjar, and Souad El Hajjaji. 2026. "Life-Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment: Enhancing Sustainability Through Process Optimization" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020605

APA StyleLaouane, H., El Joumri, L., Halhaly, A., Arid, Y., Labjar, N., & El Hajjaji, S. (2026). Life-Cycle Assessment of Wastewater Treatment: Enhancing Sustainability Through Process Optimization. Sustainability, 18(2), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020605