1. Introduction

The consequences of climate change constitute one of the foremost global challenges of the 21st century, necessitating transformative mitigation and adaptation measures to strengthen system resilience and facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy [

1,

2]. Addressing this complex challenge requires not only substantial emission reductions and large-scale deployment of renewable energy, but also the adoption of complementary strategies aimed at enhancing sustainability, fostering a structural transformation of the energy system, and ensuring progress toward international climate goals [

1,

3]. Meeting the “net-zero emissions” target outlined in the

Paris Agreement (2015) [

3] requires going beyond conventional mitigation strategies, by integrating carbon capture solutions combined with utilization and/or storage (CCUS) [

4]. Industrial emissions are particularly challenging, as growing demand for industrial products is expected to increase GHG emissions while abatement options remain limited [

5]. Efficiency improvements and low-carbon energy inputs (e.g., electrification or hydrogen) can reduce energy-related emissions, but not process-related ones, making industry a hard-to-abate sector [

6]. CCUS offers a promising solution, capable of removing up to 90–99% of energy-related and process emissions, and its limited deployment has prompted strong investment from governments, industry, and research institutions to accelerate its development [

6,

7,

8]. In Europe, significant financial resources have been allocated to support the development and deployment of CCUS technologies [

9]. This commitment is exemplified by several high-profile projects, such as the Northern Lights project [

10], the 3D initiative by ArcelorMittal [

11], the HyNet cluster in Northwest England [

12], and the Ravenna Hub led by SNAM and ENI [

13], reflecting the region’s proactive efforts to advance large-scale decarbonization through carbon capture, utilization, and storage. Furthermore, Celanese Corporation, in partnership with Mitsui & Co., Ltd., has launched a CCU initiative under the Fairway Methanol joint venture [

14]. In parallel, major CO

2 storage projects such as

Bifrost in Denmark [

15],

Aramis in the Netherlands [

16] and

Iroko in Norway [

17] are currently under development.

CCUS technology involves three sequential stages. The first stage is carbon capture, which can be achieved through various approaches, including pre-combustion, post-combustion, and oxy-fuel combustion [

2]. The second stage involves compressing CO

2 to make it ‘

transport-ready’, typically at a temperature of 15 °C and a pressure of 150 absolute bar [

18]. Finally, the third stage concerns either the utilization of CO

2 (CCU) or its storage (CCS) or both (CCUS) [

19,

20]. With respect to CCU, it is well established that captured CO

2 can be converted into e-fuels [

21].

The authors have pursued an extensive research agenda in the power generation field, with a particular focus on the rigorous performance characterization of plants integrating CO

2-mitigation frameworks. Their investigations have encompassed both traditional and advanced thermodynamic configurations [

22]. In these investigations, the CO

2 capture and compression/liquefaction units were assessed through a black-box analysis framework. Nevertheless, a comprehensive evaluation of the compression and liquefaction processes is crucial, considering their substantial influence on the overall energy performance of the plant and the spatial demands of their implementation.

Another critical component of CCUS systems relates to the transportation of CO

2 from emission sources to storage or utilization sites. Existing studies indicate that pipeline-based CO

2 conveyance, particularly when operated in the supercritical regime, constitutes the most robust and cost-effective option for transporting large mass flows across intermediate distances, generally below approximately 1000 km [

18,

23]. Regarding the compression phase, CO

2 can be pressurized through different pathways. For instance, in the previous study [

24], the authors developed a preliminary design of turbomachinery based on multi-stage gaseous compression, ultimately achieving supercritical conditions. On the other hand, the compression pathway may involve liquefaction of CO

2 at a specified pressure after the initial stages, with the subsequent compression performed in the liquid phase to reach the pressure required for ‘

transport-ready’ conditions. Implementation of this pathway requires the integration of a chiller system into the compression process. In relation to the chiller system, various solutions are currently available, differing in the type of working fluid and the thermodynamic cycle employed, such as transcritical or subcritical configurations [

25,

26]. Selecting the working fluid is critical for both chiller performance and reducing its impact on climate change [

27]. In fact, according to Montreal protocol [

28], the selection of refrigerants must take into account their ODP and GWP values [

27]. Natural refrigerants have recently emerged as very promising alternatives, particularly in the context of mitigating climate change [

26]. Among the most widely recognized natural refrigerants are carbon dioxide (R-744) and ammonia (R-717) [

29,

30]. Water (R-718) and air (R-729) are also environmentally benign refrigerants; however, their practical application is limited by the large size of system components required and the relatively low coefficients of performance (COP) that can be achieved [

30]. Therefore, in this work, the authors selected ammonia as the refrigerant, operating in a subcritical cycle. In addition to its positive environmental effects, the use of ammonia is characterized by very low power consumption and the ability to provide a significant cooling/heating capacity [

31].

Based on these considerations, this paper focuses on exploring alternative compression pathways within the context of CCS applications integrated into a power plant (

Figure 1). Two different pathways are proposed, both of which involve the liquefaction of CO

2 following an initial compression phase. The main distinction between these two alternatives is the CO

2 condensing pressure, which influences the system performance and design requirements of compressors and pumps to achieve the CO

2 ‘transport-ready’ condition. Compared to existing literature, this study reports the complete outcomes of the preliminary compressor and pump design, outlining the kinematic and thermodynamic parameters of each turbomachinery stage, the geometric parameters to assess the spatial requirements of the proposed solutions, and the isentropic efficiency. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was carried out on the centrifugal compressors designed to evaluate the influence of key parameters, including flow rate coefficients, blade loading coefficients, and degree of reaction, on compressor performance. Finally, the alternative proposed in the previous work [

24], based on IGC solution, is compared with those presented in this paper in order to identify the optimal compression/liquefaction configuration for achieving the CO

2 ‘

transport-ready’ condition in terms of energy consumption.

The case study focuses on an advanced ultra-supercritical steam power plant, RDK8 Rheinhafen-Dampfkraftwerk in Karlsruhe, Germany, which features a nominal net thermal efficiency of 47.5% and a net electrical output of 919 MW. Among coal-fired steam power plants in operation today, RDK8 exhibits the highest efficiency worldwide. It is assumed that the power plant is equipped with a post-combustion capture unit capable of capturing 90% of the CO2 emissions.

Figure 1.

Scheme of CCS process integrated in a power plant [

24].

Figure 1.

Scheme of CCS process integrated in a power plant [

24].

The authors implemented custom MATLAB 2024b codes and integrated NIST Refprop [

32] sub-routine to accurately evaluate the thermodynamic properties of the process working fluids. The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 first provides a brief description of the case study, then presents the thermodynamic analysis, followed by the preliminary design of the pumps, and concludes by highlighting the main design parameters and assumptions used to evaluate the refrigeration systems.

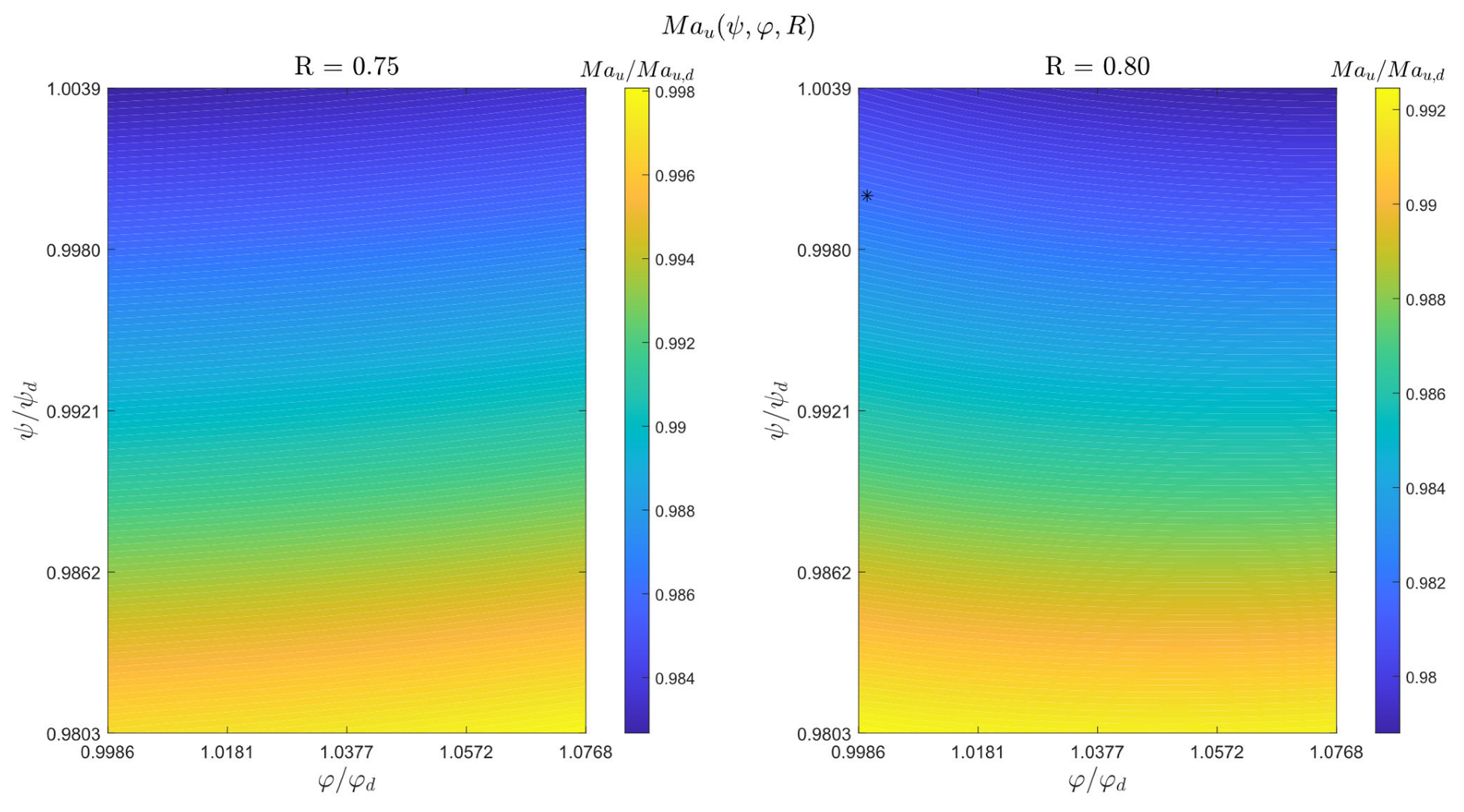

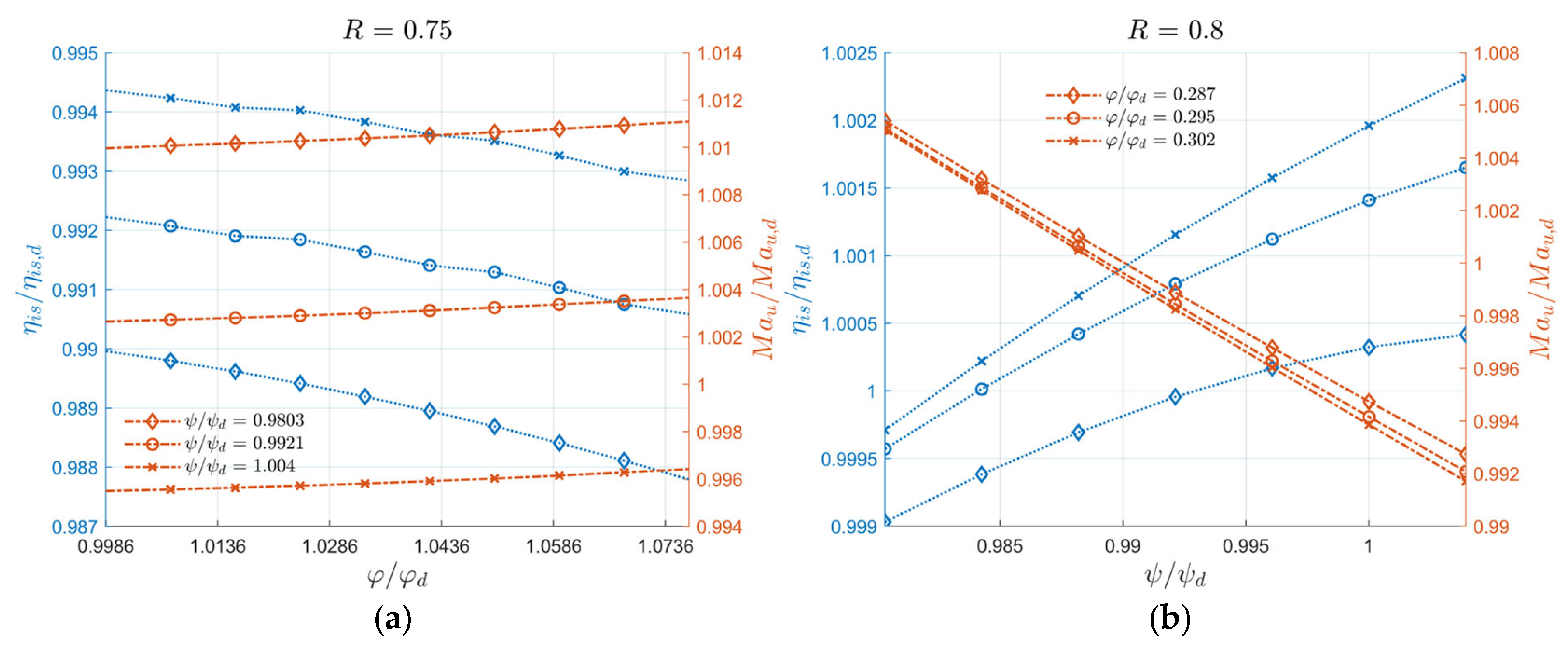

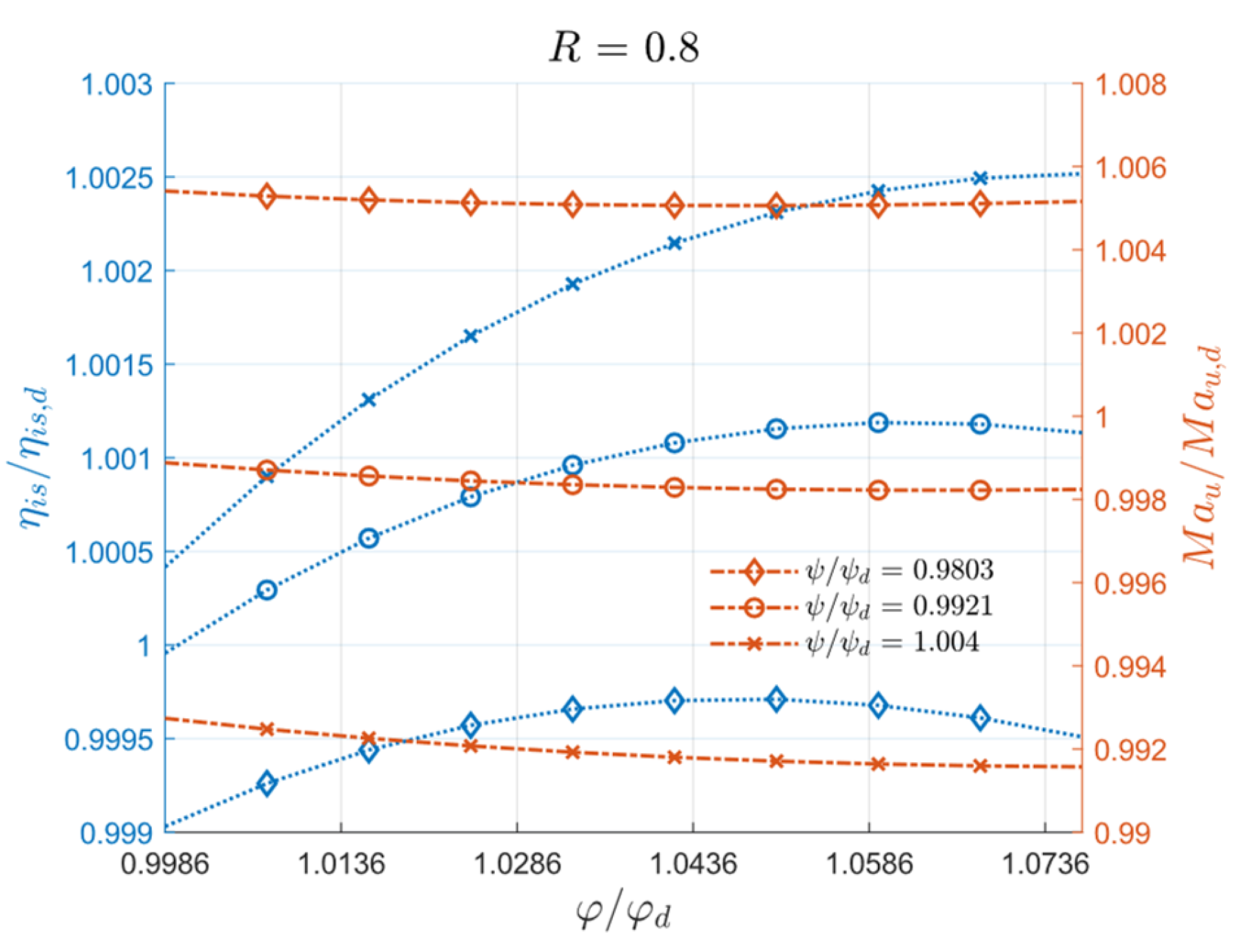

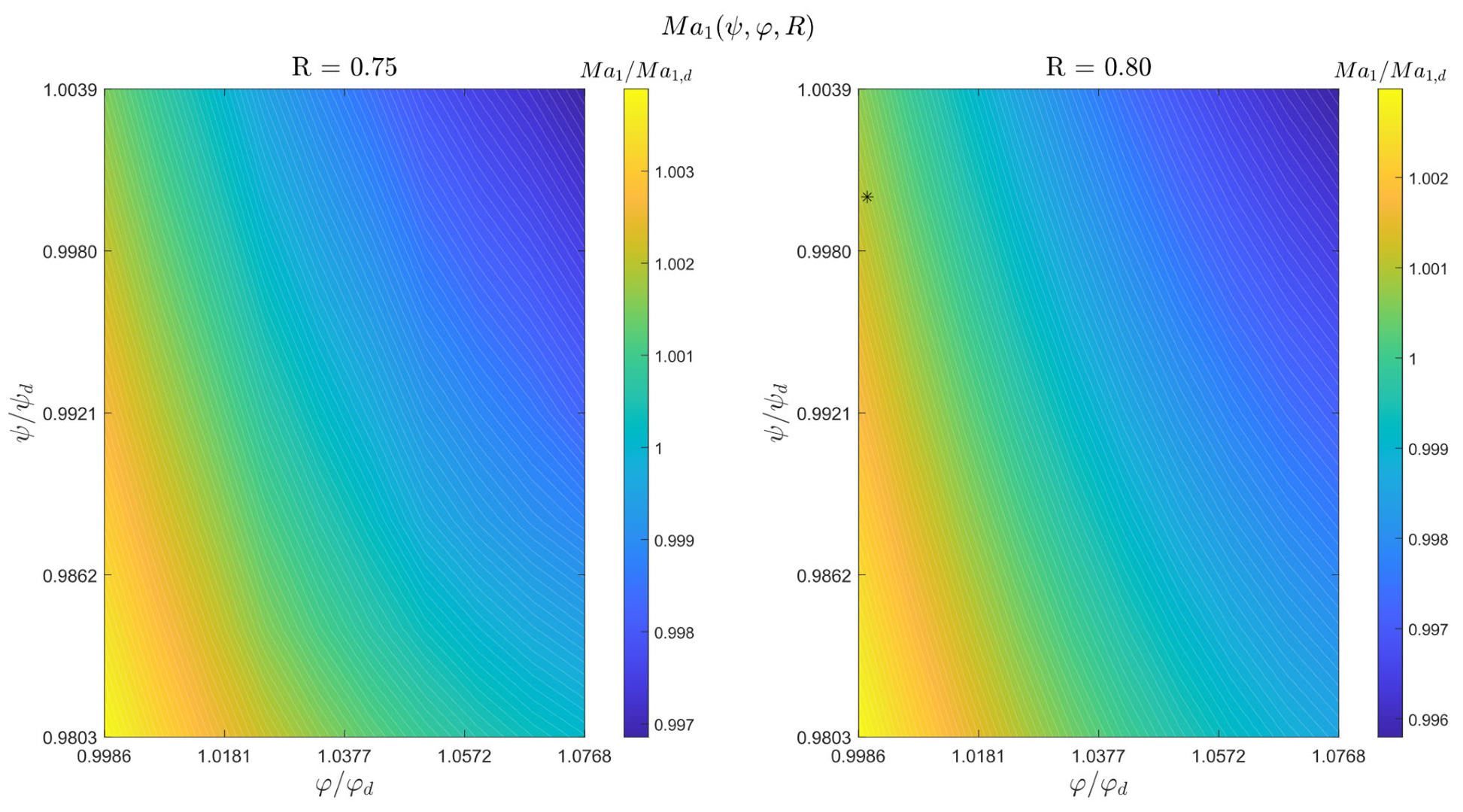

Section 3 presents the results, beginning with the selection of compressors and pumps, followed by the preliminary pump design. It then reports the performance of the refrigeration systems for the three compression pathways and concludes with a sensitivity analysis on turbomachinery design, focusing on peripheral Mach number, isentropic efficiency, and Mach at inlet conditions, and the energy balance of the proposed layouts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

As outlined in the introduction, this paper examines the CO

2 compression system of an advanced ultra-supercritical coal-fired steam power plant, specifically the RDK8 Rhein-hafen-Dampfkraftwerk located in Karlsruhe, Germany [

33]. It is important to highlight that the CO

2 separation process employed corresponds to post-combustion capture technology (

Figure 1). The parameters used for quantifying the amount of CO

2 generated and subsequently separated are summarized in

Table 1.

The CO

2 mass flow rate in the compression system has been evaluated in the previous work [

24] and it is approximately equal to 200 kg/s.

2.2. Thermodynamic Analysis

To achieve transport-ready conditions, CO

2 must be in the liquid phase. In the authors’ previous work, the compression process was analyzed under supercritical gaseous conditions, since the minimum temperature was set at 35 °C.

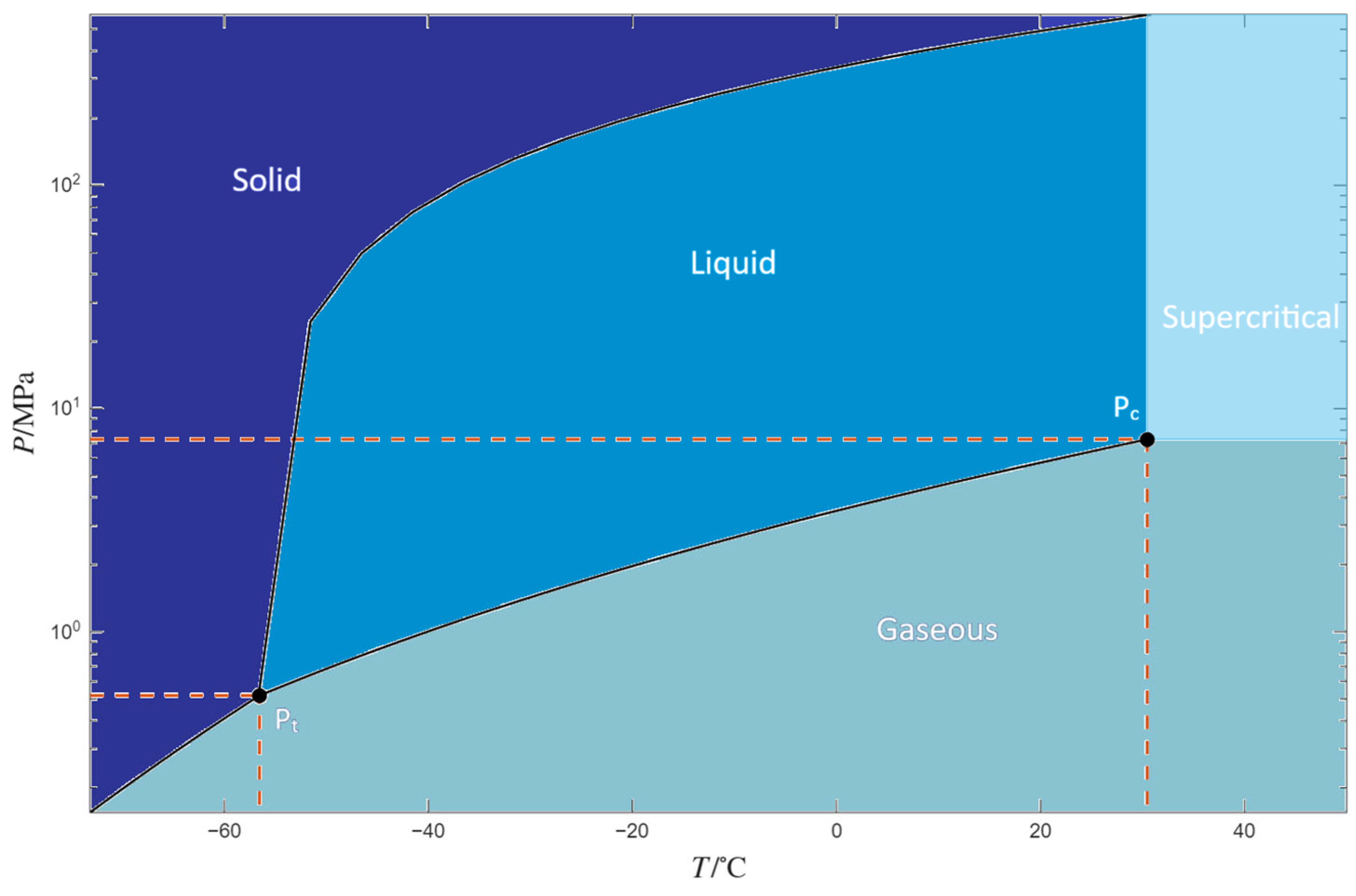

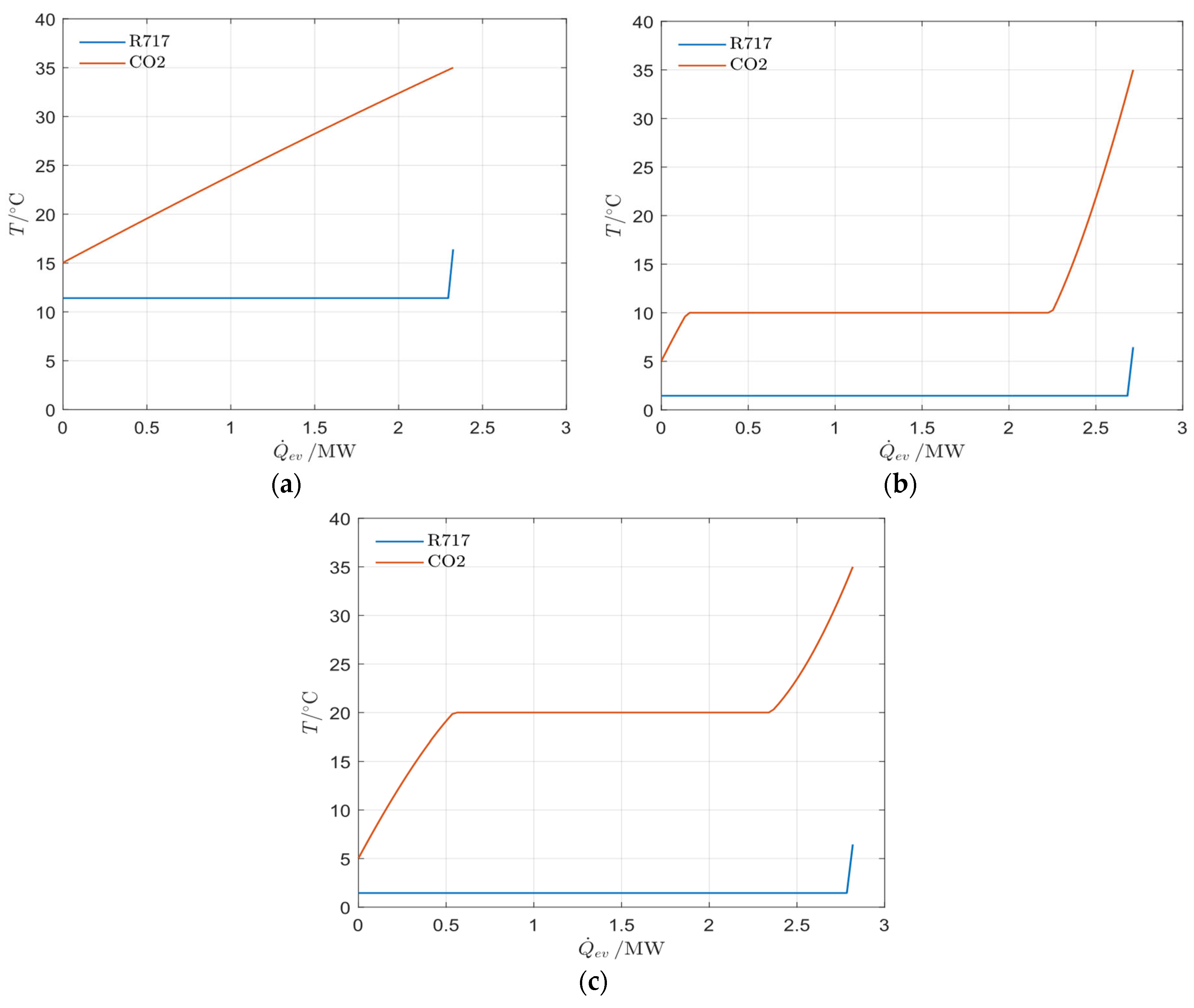

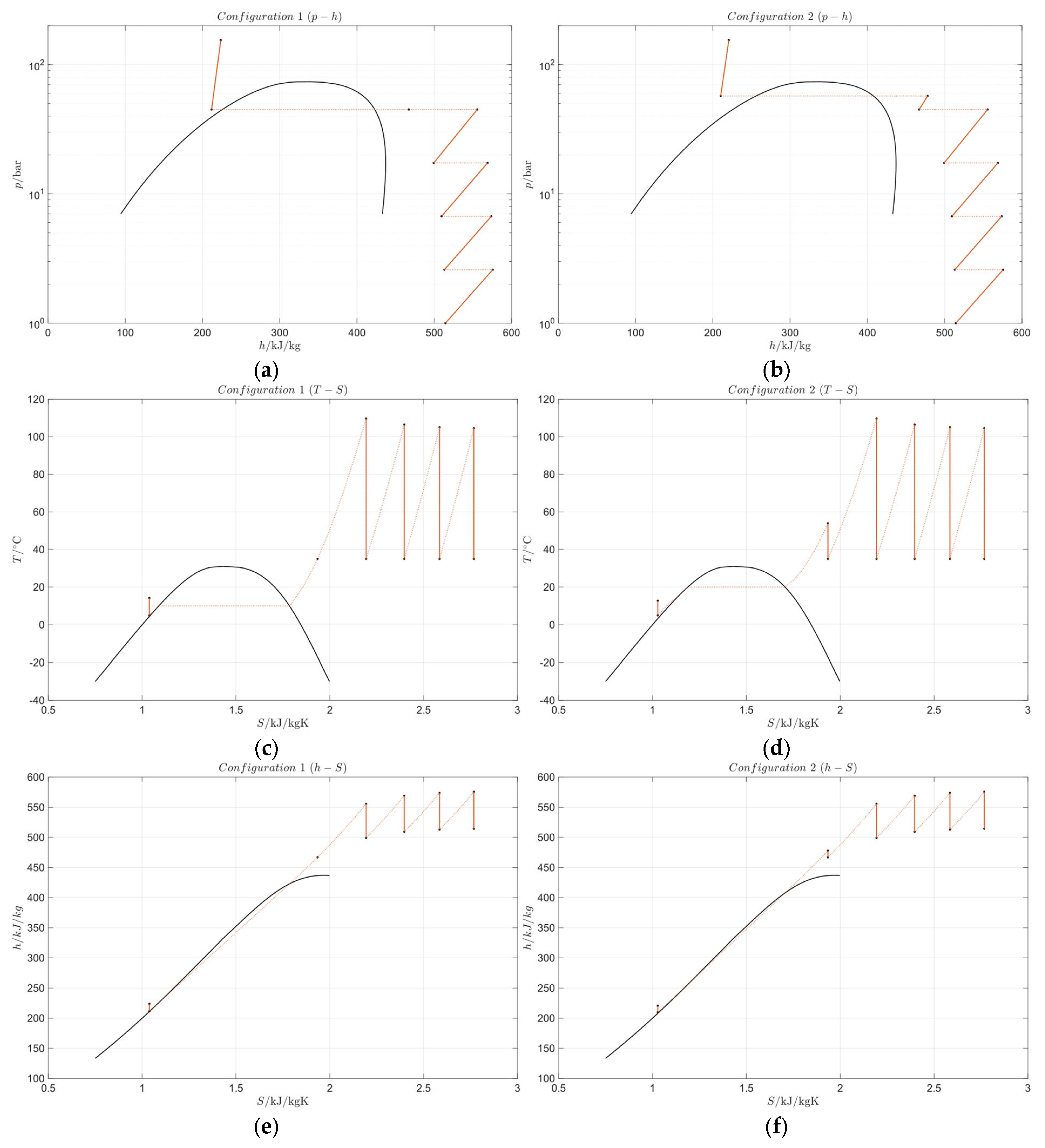

Figure 2 shows the CO

2 phase diagram. In the present study, the effect of CO

2 liquefaction at an intermediate pressure—ranging between 40 and 60 absolute bar—is investigated to assess the system’s energy consumption and the complexity of the plant layout (in terms of the number of machines and compression stages).

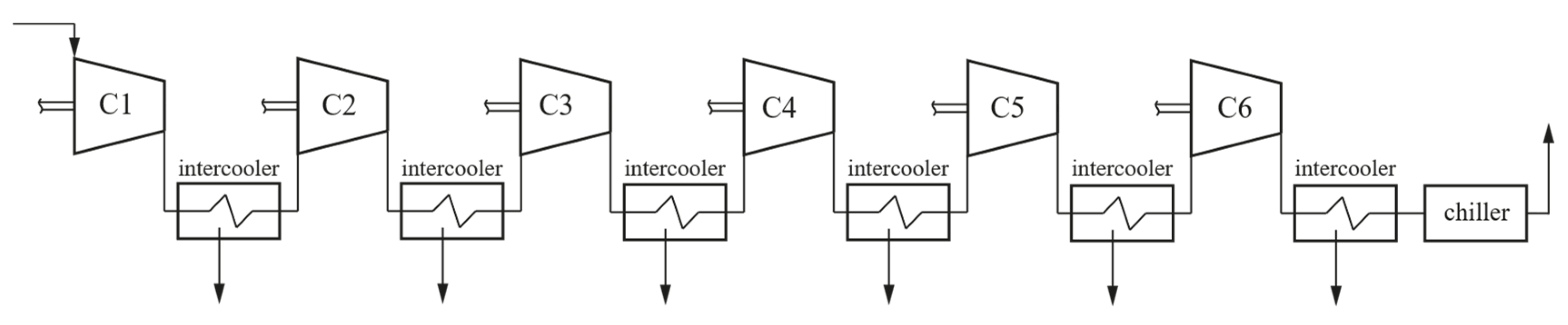

To enable a fair comparison between the configurations analyzed in this study and those presented in the previous work, the same arrangement of the first four compressors in the six-stage scheme has been maintained (

Figure 3). In addition, it is worth noting that only the IGC configuration has been considered, as previous work [

24] demonstrated advantages such as compactness with respect to both dimensions and stages.

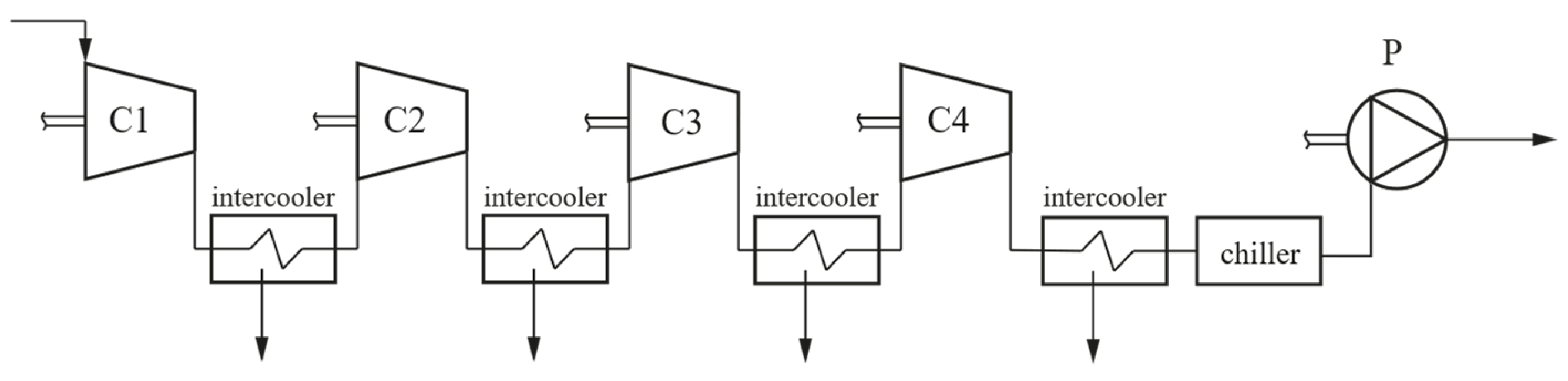

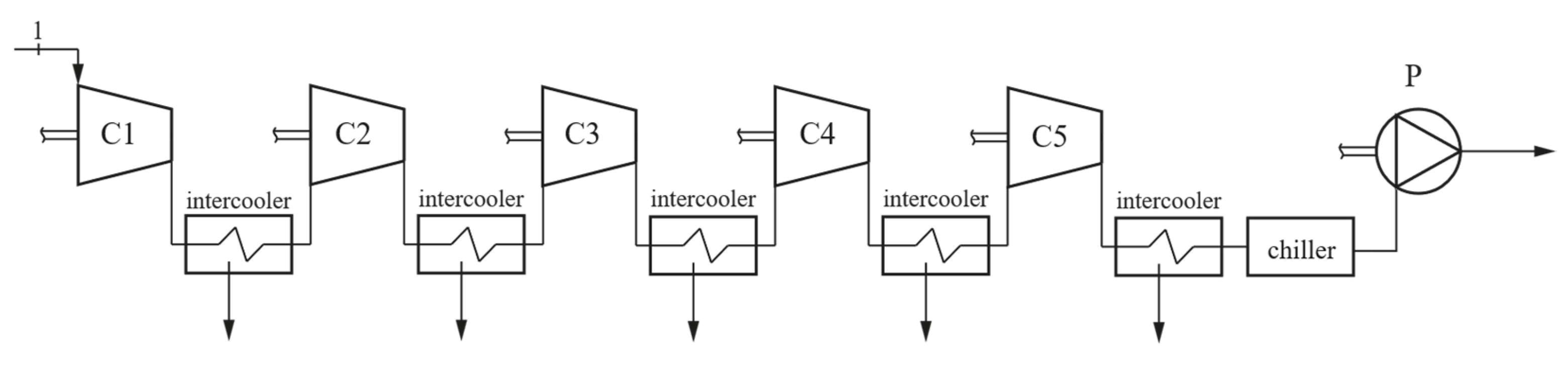

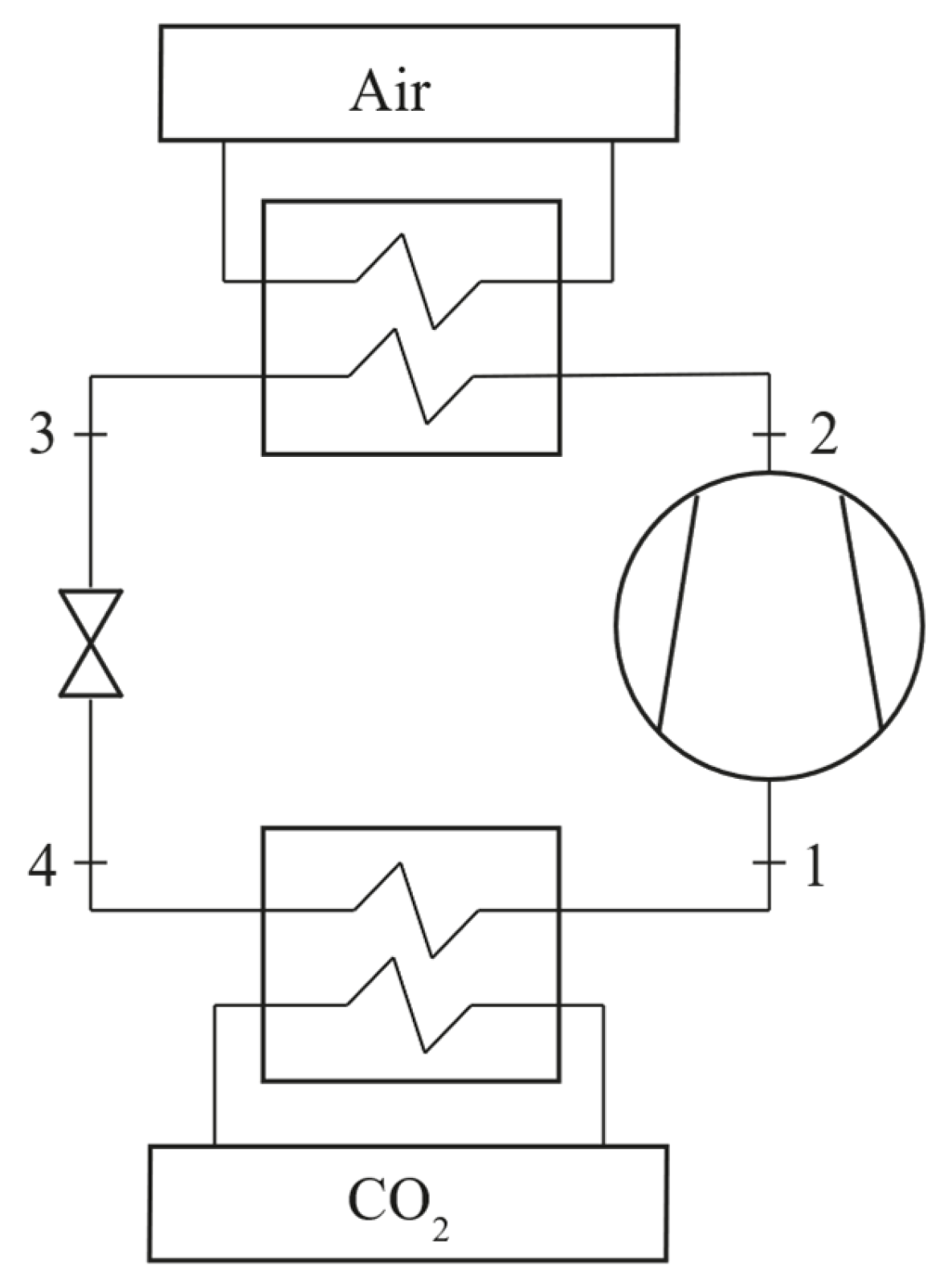

Two alternative system configurations have been proposed. In the first one (

Figure 4), the transport-ready condition is achieved through an intercooled phase following the fourth compression phase, a chiller system, and a pump. In the second configuration (

Figure 5), an additional compression process in gaseous phase and an intercooled phase are introduced before the chiller system and the final pumping process. Therefore, the main difference between the two proposed configurations lies in the distinct CO

2 condensation temperatures, set at 10 °C for the first configuration and 20 °C for the second, both values being compatible with refrigeration systems.

Figure 2.

CO2 phase diagram.

Figure 2.

CO2 phase diagram.

Figure 3.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 0.

Figure 3.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 0.

Figure 4.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 1.

Figure 4.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 1.

Figure 5.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 2.

Figure 5.

Analyzed plant layout scheme 2.

Figure 6 illustrates the transformations involving CO

2 as represented on the thermodynamic charts. It is important to emphasize that ideal transformations were initially assumed as a starting point for the preliminary design, in order to divide the overall compression ratio among the individual compressors in a consistent manner. As highlighted in the previous study [

24] the thermophysical behavior of CO

2 ensures a relatively uniform distribution of specific compression work across the first four stages within the considered pressure range between 1 and 45 absolute bar.

In Layout 2, in addition to the pump, a gas-phase compression is required, for which the enthalpy change (reversible work) through compressor C5_2 is comparable to that of the pump P_2.

2.3. Selection and Preliminary Design Pump

It is worth highlighting that this section only presents the selection and preliminary design procedure of pumps, as that concerning the compressors has already been described in a previous work [

24].

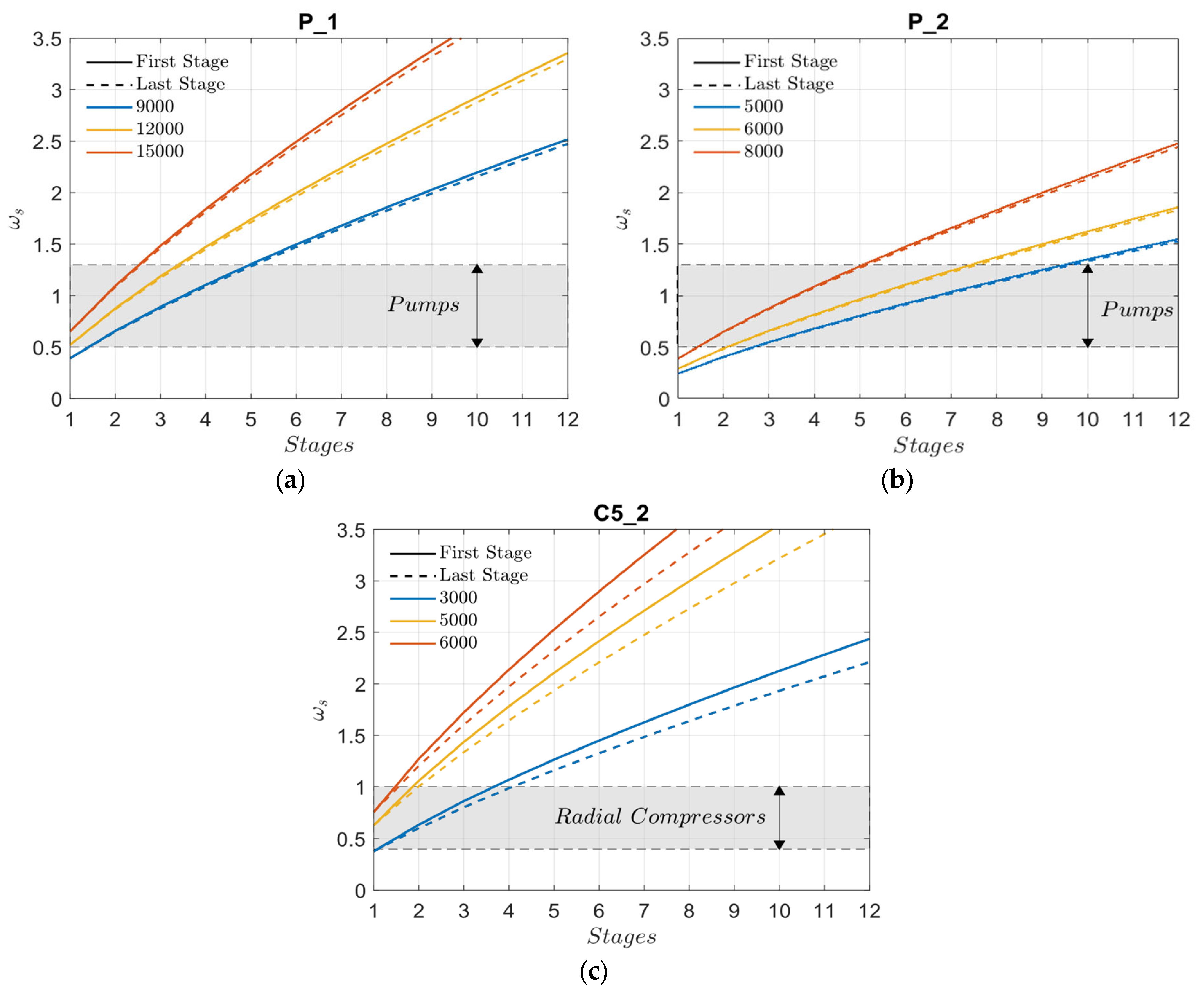

The similarity theory, particularly as formulated through the Baljé method, provides a fundamental approach for classifying turbomachines (axial, radial, or mixed flow) according to their specific application. Baljé’s diagrams, in particular, enable the identification of characteristic ranges of specific speed that define the suitability of each turbomachine type [

35].

Accordingly, selecting the appropriate turbomachine type requires a preliminary estimation of the specific speed, based on the available operating data, which includes:

The working fluid;

m: mass flow rate (kg/s);

Tin: inlet temperature of the fluid (°C);

pin: inlet pressure of the fluid (bar);

pout: outlet pressure of the fluid (bar).

These quantities allow to evaluate the ideal specific work of the machine, which corresponds to the head in hydraulic machines,

. In addition, the pump head has been considered in the evaluation of the specific speed which also depends on the rotational speed (

, rad

, or rpm), number of stages

and the volumetric inlet flow rate

. For pumps, the specific speed is expressed as:

In this context, it is necessary to establish a criterion for distributing the reversible work of the entire machine among its individual stages. Once this distribution has been defined, the volumetric flow rate at the inlet of each pump stage can be evaluated. This evaluation is performed by calculating the pressures and temperatures upstream and downstream of each stage based on the ideal head increment , and subsequently determining the associated volumetric flow rates. It is important to note that, in pumps, the volumetric flow rate varies only slightly between the inlet and the outlet due to the relatively small change in fluid density. For this reason, selecting a specific number of stages, the specific speeds at the first and last stages are approximately equal.

This step in the pump selection process determines the feasible values of the rotational speed () and the number of stages () that ensure an appropriate specific speed, that would be within the range of values for high-hydraulic efficiency pumps which falls in 0.5–1.3, consistent with the desired machine size and compliant with possible rotational-speed constraints, such as cavitation limits.

The preliminary design of the centrifugal pump is carried out stage by stage, following the sequential order below [

36]:

- 1.

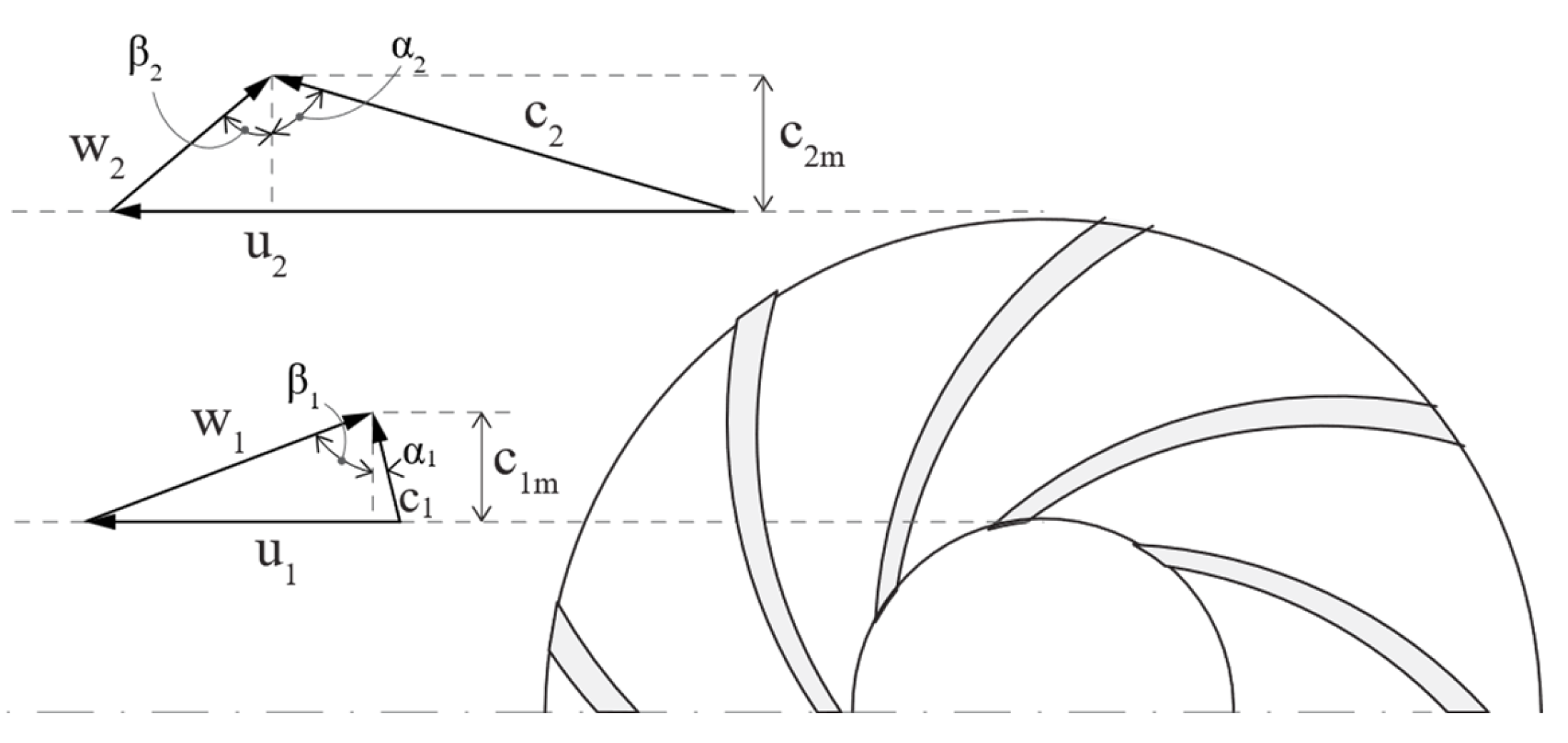

Evaluation of kinematic parameters: The kinematic angles at the rotor inlet and outlet (

,

Figure 7) are determined by setting the following five independent parameters:

The flow coefficient, here defined as ;

The work coefficient, here defined as ;

The rotor meridional velocity ratio: ;

The rotor tip diameter ratio: ;

The angle .

Thus, the following is obtained:

Therefore, the peripheral velocity can be used to define the stage kinematics fully. To calculate , the parameter must be specified, along with an initial estimate of the hydraulic efficiency, which will be updated once the stage is fully defined.

Figure 7.

Velocity triangles in a radial pump stage (adapted from [

36]).

Figure 7.

Velocity triangles in a radial pump stage (adapted from [

36]).

- 2.

Evaluation of thermodynamic parameters: Knowing the pressure and temperature at the stage inlet, along with the pressure at the stage outlet, allows the determination of the thermodynamic states at the rotor inlet and at the stator inlet and outlet.

In this case if the density can be considered almost constant throughout each stage, the pressure at the rotor outlet can be calculated using the rotor hydraulic efficiency, defined as:

If, in addition to the six input previously introduced parameters, an initial estimate of the rotor hydraulic efficiency is provided (which will be updated once the stage is fully characterized), all thermodynamic properties of the stage can then be calculated.

- 3.

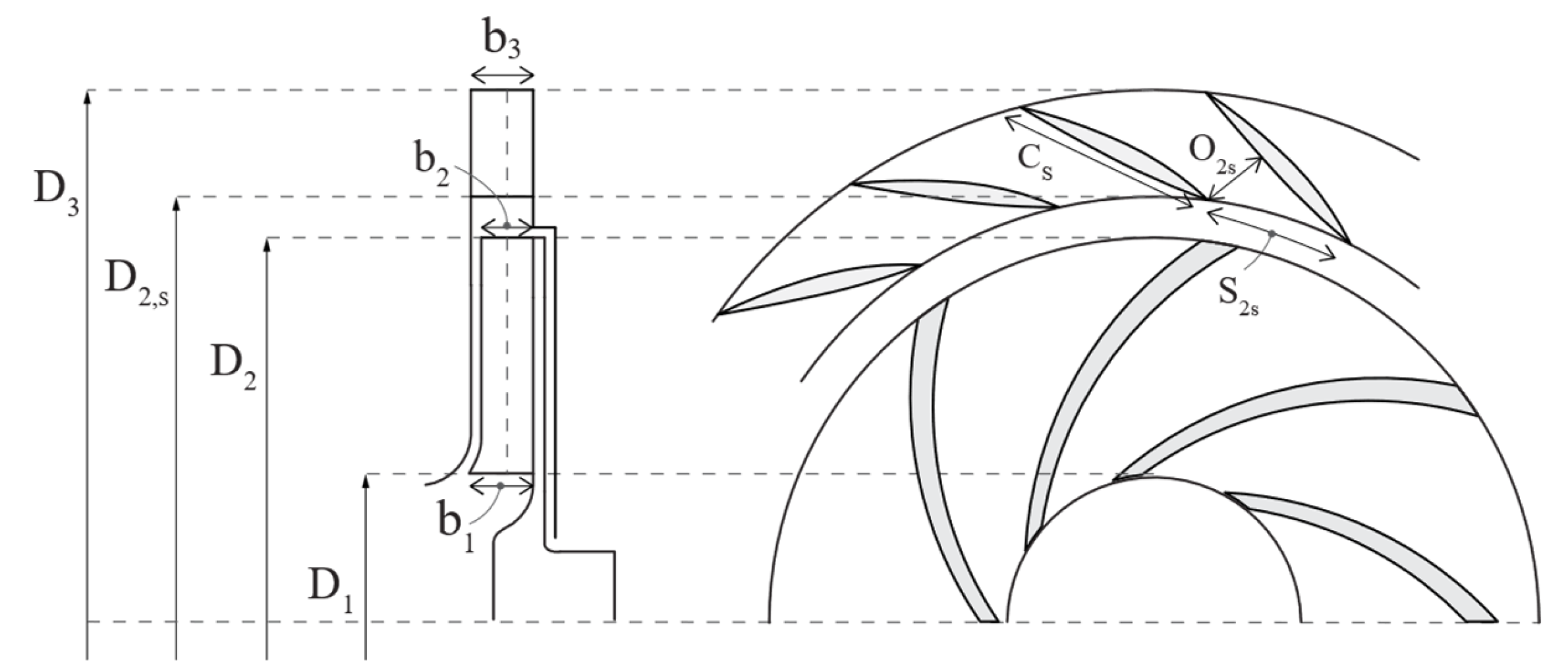

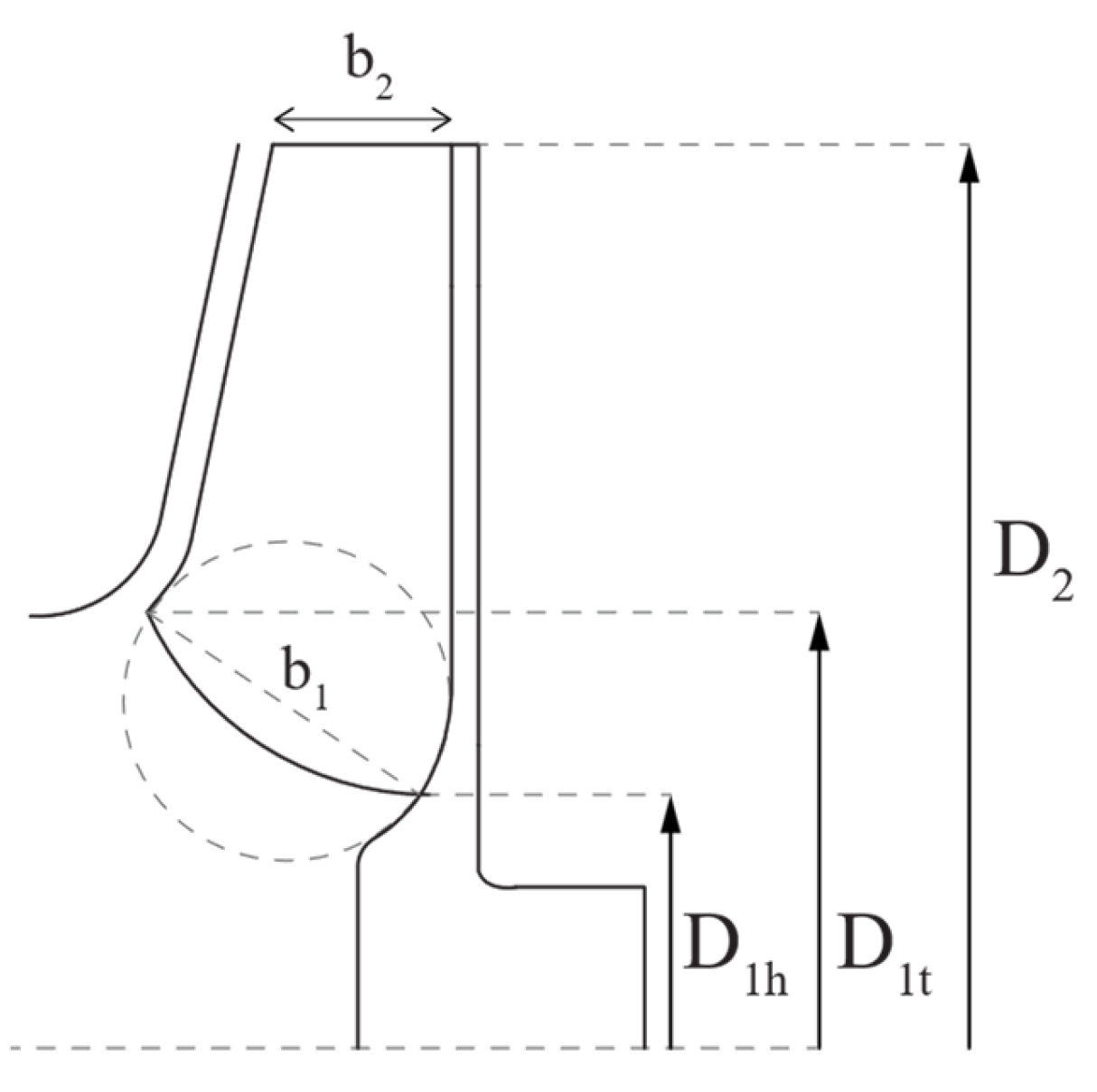

Assessment of geometric parameters:

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate the key geometric parameters of a radial stage, corresponding to radial inlet flow and mixed inlet flow, respectively. It is worth noting that the evaluation of geometric parameters involves defining an equivalent rotor channel with a circular section characterized by a hydraulic diameter and a hydraulic length. The outlet flow angle differs from the blade angle, since the fluid does not perfectly follow the geometry defined by the blades. By expressing the slip factor as a function of the outlet flow angle and the number of blades, and using additional correlations suggested by Gulich [

37], the outlet flow angle has been defined. At the rotor outlet, the stator typically consists of a vaneless diffuser followed by a vaned diffuser. Following Gulich’s recommendations [

37], the geometries of both the vaned and vaneless diffusers can be defined, nevertheless some constraints must be satisfied: for example, the number of stator blades can be selected in correlation with the number of rotor blades in order to limit pressure pulsations and vibrations.

- 4.

Losses and stage efficiency evaluation: For any type of turbomachinery, the authors [

38] have extensively described the main sources of losses and the corresponding loss models suitable for preliminary design. In this paper, the loss model proposed by Gulich is adopted [

37], where losses are expressed in terms of head (meters). The losses within the stator and rotor of a radial stage—where

represent stator losses and

rotor losses—are influenced by the kinematic, thermodynamic, and geometric parameters of the stage. After determining these losses, the rotor and overall stage efficiencies can be easily derived as functions of the stage work input and the corresponding energy losses. Then:

If the calculated stage efficiency satisfies the design specifications, the sizing procedure can be considered complete; otherwise, the input parameters should be modified and a new sizing iteration carried out.

Figure 8.

Impeller inlet geometry: radial (adapted from [

36]).

Figure 8.

Impeller inlet geometry: radial (adapted from [

36]).

Figure 9.

Impeller inlet geometry: mixed (adapted from [

36]).

Figure 9.

Impeller inlet geometry: mixed (adapted from [

36]).

For multistage pumps, the same calculation procedure is repeated for each stage. Between two consecutive stages, a volute is assumed in which the total enthalpy, mass flow rate, and angular momentum remain constant, provided that frictional effects are negligible. Based on these assumptions, the subsequent stages can be assessed by appropriately redefining the six input parameters.

Although summarized here, the procedure highlights that the design of a centrifugal pump stage essentially depends on six main input parameters, given the fluid type, mass flow rate, inlet temperature and pressure, outlet pressure, rotational speed, and number of stages. As noted in [

36], the previously introduced parameters (

correspond exactly to another parameter set (

, designated as set B. In the latter, the first four quantities can be expressed as functions of the stage specific speed, whereas the remaining two parameters can be reasonably fixed at 0° and 0.30, as suggested in [

36]. Within Set B, the two rotor diameter ratios—

and

—replace the flow coefficient as independent input parameters. In this regard, Gulich [

37] suggested evaluating the optimum value of

for the cavitation avoiding, whereas

as a function of the specific speed:

Nevertheless, introducing the parameter

and

, it is possible to determine the flow coefficient as function of

:

Therefore, having established the optimal ranges of the specific speed for high-efficiency centrifugal pump stages [

35] the design procedure for the single stage based on set B requires knowledge of only two input parameters, thus becoming a guided procedure. Following the design stage, it is essential to perform a thorough validation of the resulting parameters to ensure they lie within the optimal ranges reported in the relevant technical literature.

2.4. Chiller Design Assumptions

This section summarizes the main design parameters and assumptions used to evaluate the performance of the subcritical reverse cycles. First, as highlighted in the Introduction, ammonia (R-717) was selected as the working fluid. This decision followed a preliminary assessment comparing a subcritical ammonia cycle with a transcritical CO

2 cycle. Starting from the external fluid, the following

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 report the inlet and outlet temperatures, pressures, and cooling capacities. For all chillers considered, the external fluid in the condenser is air at ambient pressure with an identical temperature profile, whereas in the evaporator, the CO

2 outlet temperature varies depending on the specific case.

With respect to the evaporation temperature, it is determined by the external fluid temperature profile, the degree of superheating (

), and the minimum temperature difference between the fluids in the evaporator (

), which is specified as a design parameter. Moreover, the location of the minimum temperature difference depends on the temperature decrease in the external fluid (

) and the degree of superheating. Specifically, the minimum temperature difference occurs either at the hot end or at the cold end according to the following conditions:

In all cases, the degree of superheating was set to 5 °C, while the temperature difference in the CO

2 varies depending on the specific operating conditions. In addition, the minimum temperature difference in the evaporator was fixed at 3 °C. On the other hand, in the condenser, four key temperature differences can be distinguished: the temperature differences between the refrigerant and the external cooling fluid at the cold and hot ends (

and

), the temperature difference at the pinch point (

), where the refrigerant reaches the condensing temperature

, and the subcooling temperature difference (

) between the condensing and outlet temperatures, which has been set to 5 °C in the analyzed cases. The temperature profile of the external fluid and the pinch-point temperature difference determine the condensing temperature, which can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the temperature increase in the external fluid from the condenser inlet to the pinch point and

is the minimum temperature difference between the two fluids, which has been set to 3 °C. However, determining the precise location of the pinch point requires an iterative calculation, since it depends on the heat rate necessary to cool the superheated vapor to saturation conditions. This, in turn, is influenced by the refrigerant inlet temperature, which depends on the pressure ratio, itself governed by the condensing pressure and, consequently, by the condensing temperature. Finally, the condensing and evaporation pressures can then be found as the saturation pressures corresponding to the condensing and evaporation temperatures:

Determining the thermodynamic cycle also requires isentropic and mechanical efficiencies. In this study, the isentropic efficiency was assumed to be 0.8, reflecting the use of a volumetric compressor, while the mechanical efficiency was set to 0.9. These values were applied consistently to all three chillers considered. The chiller performance indicator is the Energy Efficiency Ratio (

) defined as follows:

where the numerator is the cooling capacity, while P represents the power required by the compressor. Finally, the chiller schematic layout has been reported in

Figure 10.