Systematic Review for Urban Flood Disaster in Managerial Perspective: Forecasting, Assessment and Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of Urban Flooding Disaster Management

3. Methodology

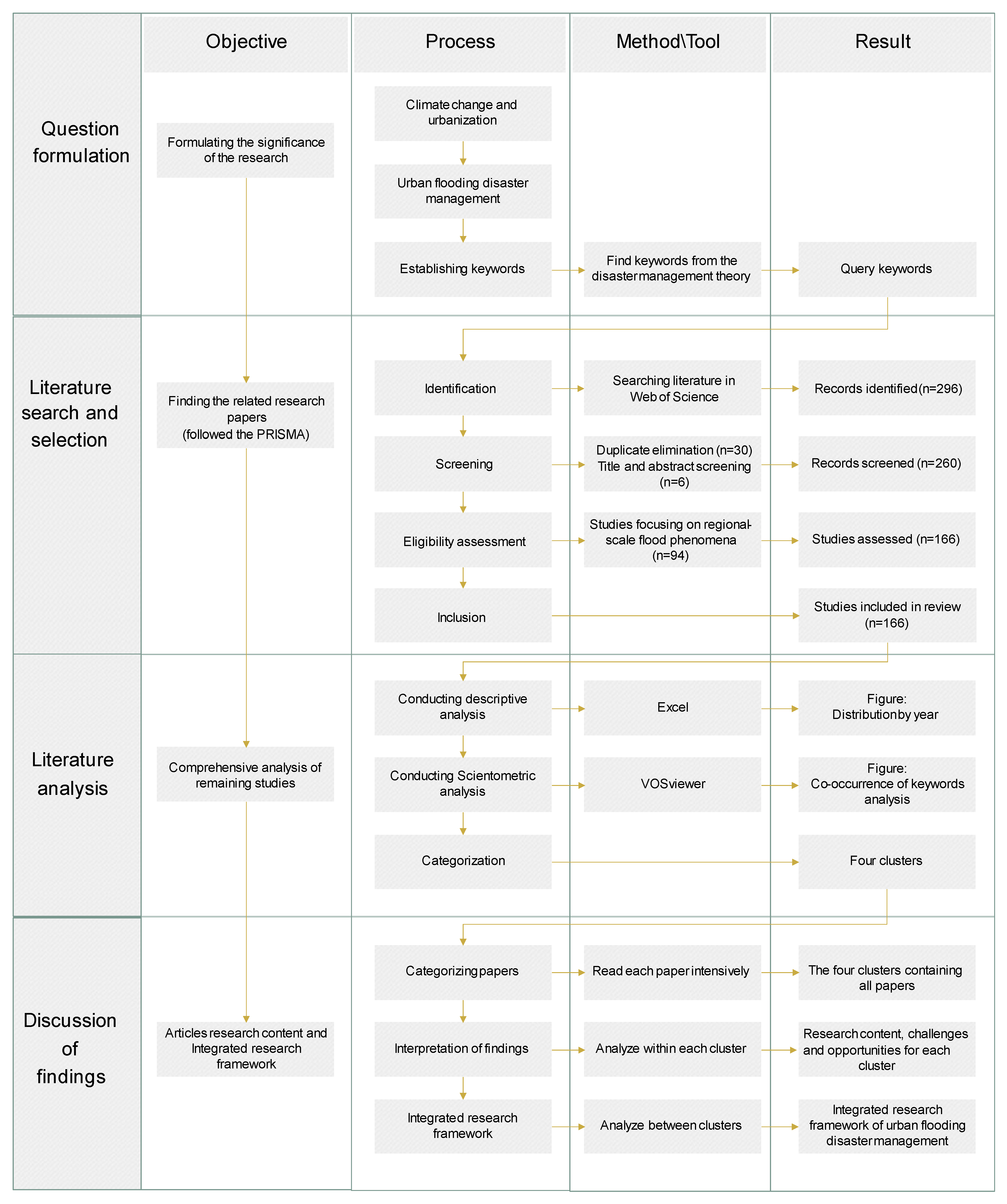

3.1. Proposed Methodology

3.2. Literature Search and Selection

3.3. Literature Synthesis Approach

- (1)

- Thematic Clustering via Scientometric Mapping: Co-citation analysis and keyword co-occurrence networks were constructed using VOSviewer to reveal latent structures and topic clusters within the field. These clusters represented dominant research dimensions such as physics-based simulation models, data-driven simulation models, risk evaluation tasks, and optimization tasks.

- (2)

- Qualitative Thematic Analysis: Each cluster was then examined through in-depth reading of the associated core articles. Key themes, methodological paradigms, research objectives, and findings were manually coded and compared. This allowed for identifying methodological patterns, knowledge gaps, and interrelationships across research domains.

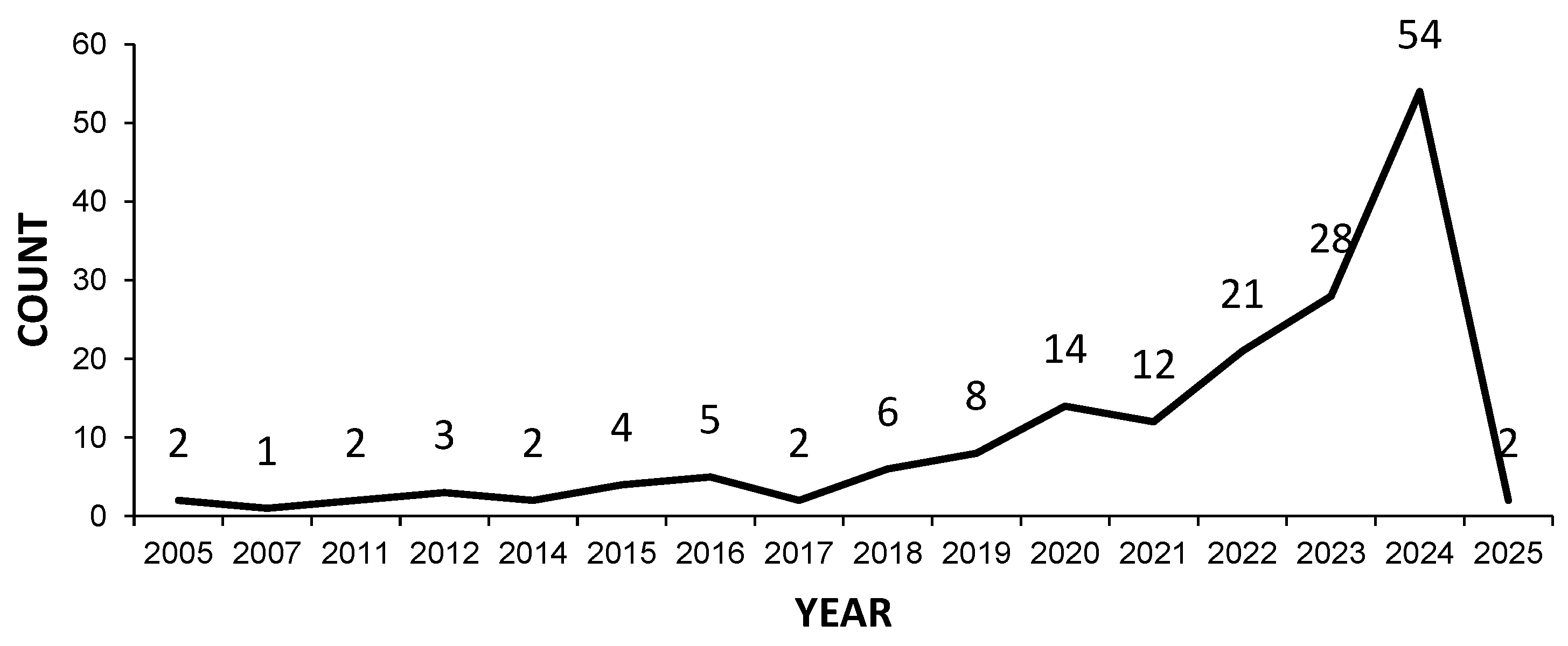

4. Scientometric Analysis

4.1. Co-Citations Analysis

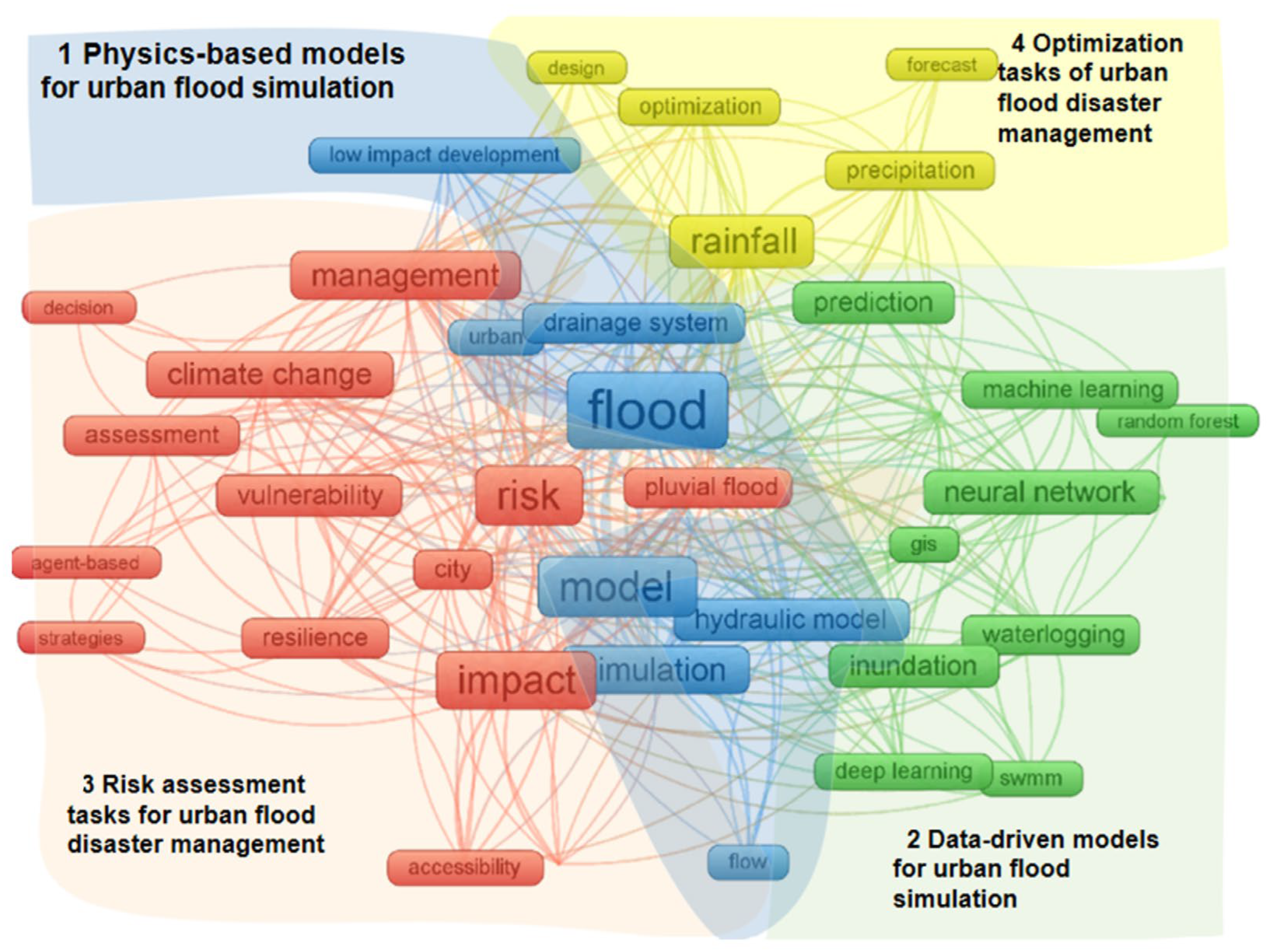

4.2. Co-Occurrence of Keywords Analysis

- (1)

- Physical simulation methods for urban flood simulation, which involve modeling and simulation of floods, drainage networks, and runoff based on physical principles;

- (2)

- Data-driven methods for urban flood simulation, including machine learning and deep learning methods;

- (3)

- Risk evaluation tasks in the urban flood disaster management process, focusing on constructing risk indicator systems for different processes of urban flood disasters, including vulnerability, accessibility, resilience, and emergency capacity; and

- (4)

- Optimization tasks in the urban flood disaster management process, emphasizing the research on perception, design, and optimization strategies and schemes; and

- (5)

- Other research, which consists of studies from diverse fields using alternative methods, such as flood governance, urban double repair, flood disaster support ontology, system dynamics, and theory of planned behavior. These papers are excluded from Figure 4 for clarity and will be separately examined in subsequent discussions. The distribution of research in these categories, as per statistical analysis, is as follows: 17% for physical simulation, 31% for data-driven methods, 21% for risk evaluation, 16% for optimization, and 16% for other literature.

5. Research Frontiers and Opportunities

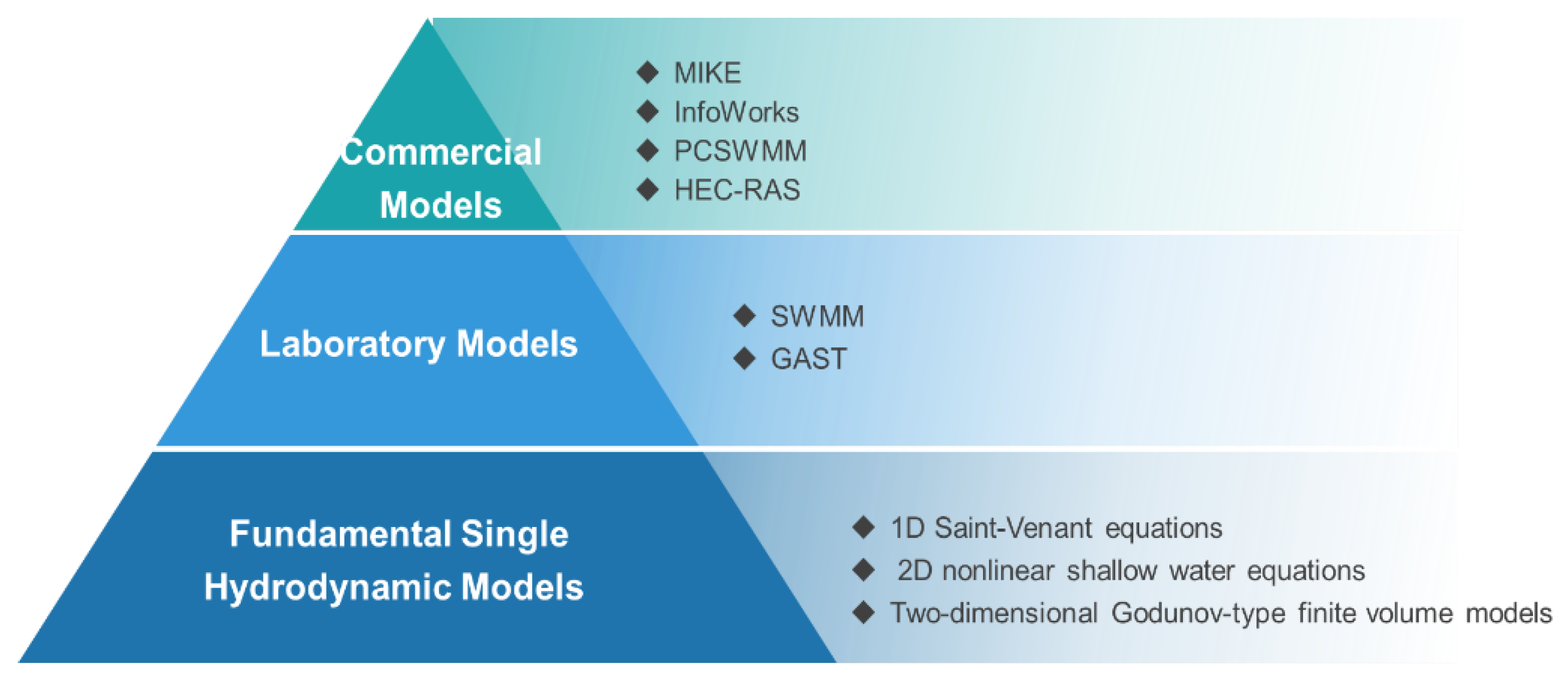

5.1. Physics-Based Models for Urban Flood Simulation

5.1.1. Literature Synthesis

| Research Objectives | Representative Papers |

|---|---|

| Enhancing data quality | Improving the accuracy of rainfall forecasts for hydrological applications (Yoon, 2019) [74] Investigate the potential of radar rainfall nowcasting in predicting flood events (Thorndahl et al., 2016) [75] Using a uniform grid of 624 × 550 units with a high resolution of 1 m (Bai et al., 2021) [76] |

| Model optimization | Applying the SWMM-LISFLOOD coupled model (Z. Zhao et al., 2024) [77] Determining hydrological model parameters using intelligent algorithms (Liao et al., 2019) [78] |

| Improve model computational efficiency | Developing a relatively coarse grid in the 2D ground surface flow model (L. Wu et al., 2022) [66] Developing the GPU parallel computing technology to improve computing efficiency (X. Li et al., 2022) [79] Impact of different building modeling approaches on model efficiency (Schubert & Sanders, 2012) [10] |

5.1.2. Challenges and Opportunities

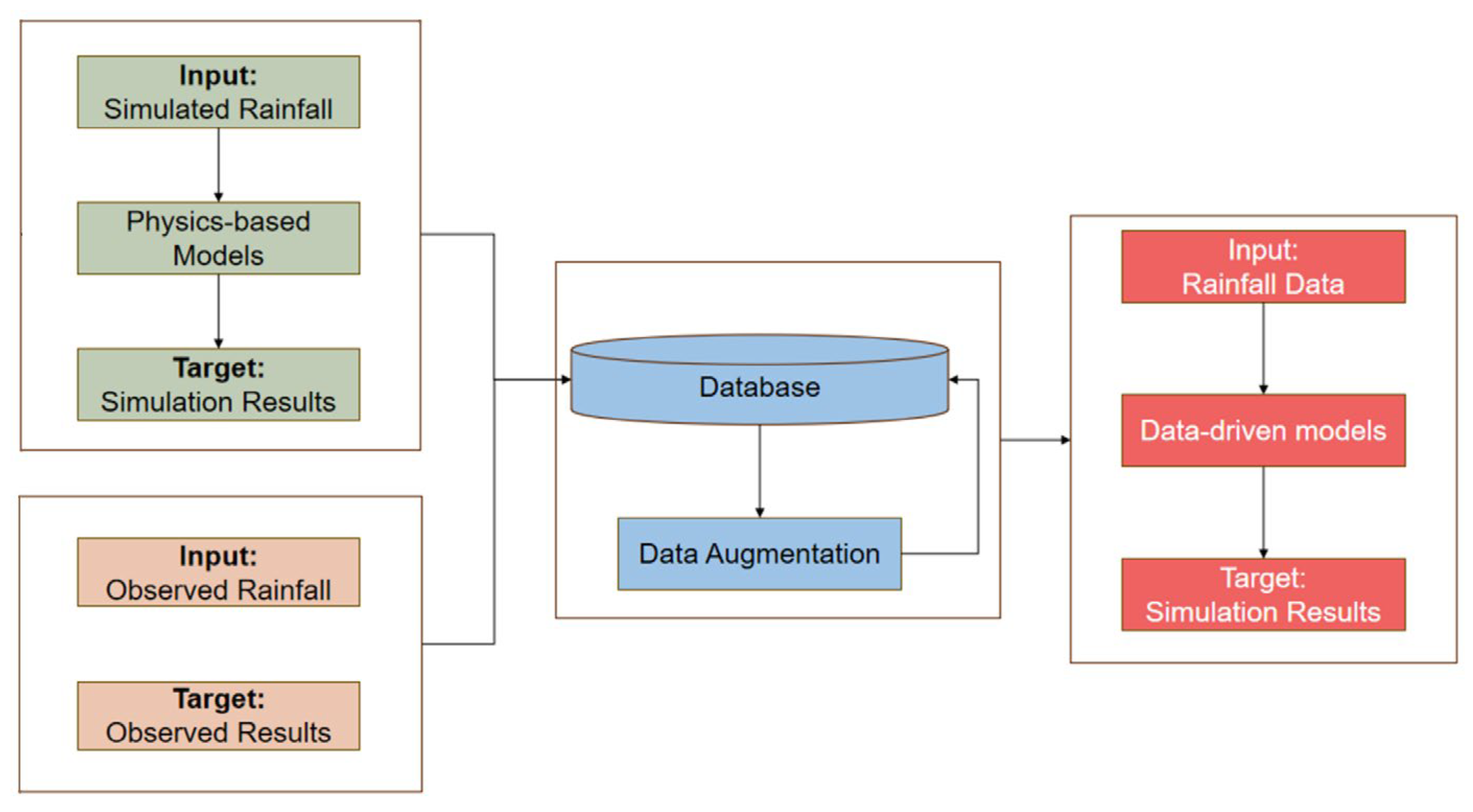

5.2. Data-Driven Models for Urban Flood Simulation

5.2.1. Literature Synthesis

5.2.2. Challenges and Opportunities

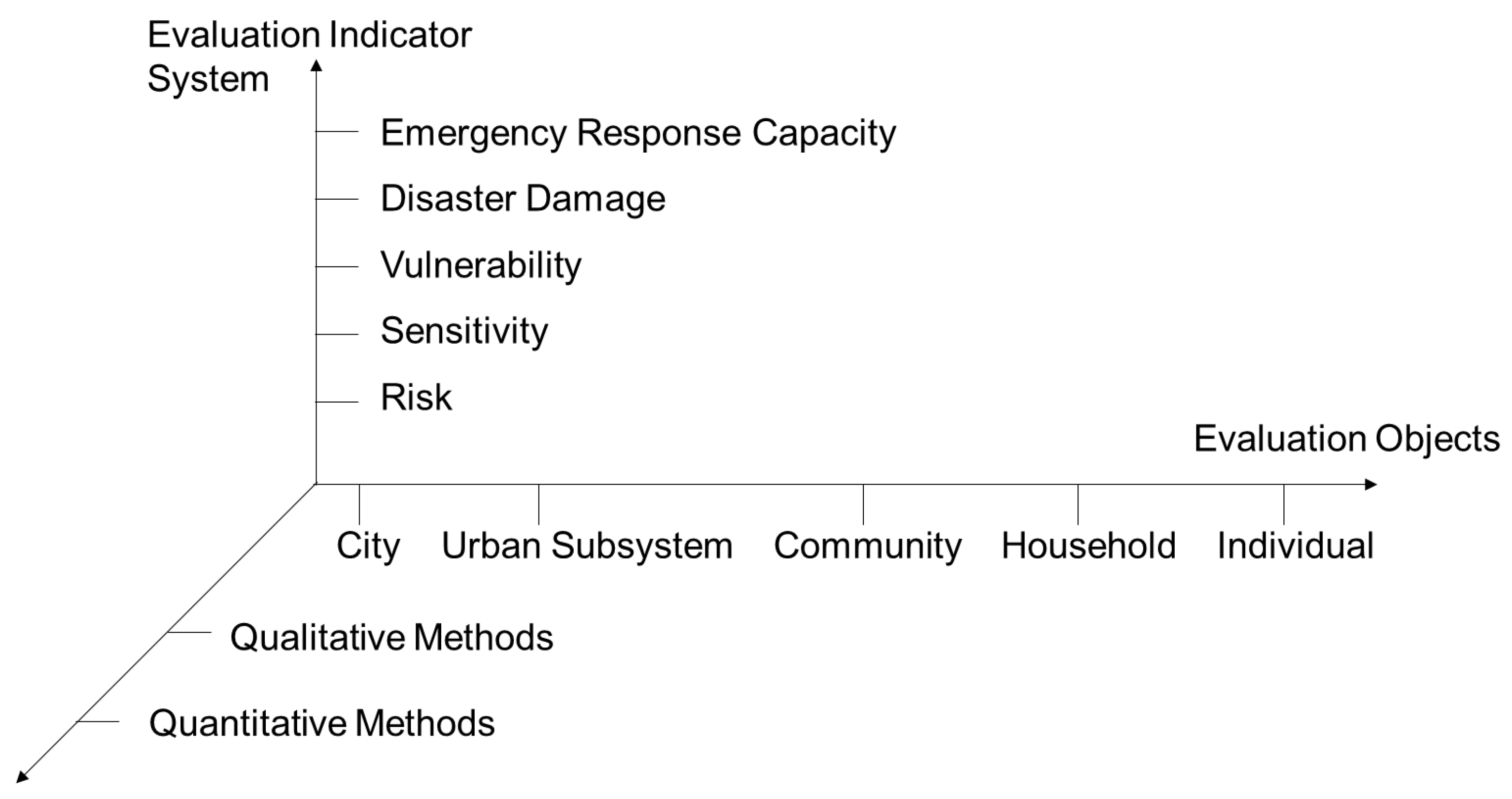

5.3. Risk Evaluation Tasks for Urban Flood Disaster Management

5.3.1. Literature Synthesis

5.3.2. Challenges and Opportunities

5.4. Optimization Tasks of Urban Flood Disaster Management

5.4.1. Literature Synthesis

| Representative Papers | Research Topics | Research Methods |

|---|---|---|

| (Sun et al., 2023) [125] | Reduce peak tank outflow | linear programming |

| (Z. Zhang, Tian et al., 2023) [126] | Leveraging infrastructure to mitigate sewer overflows (CSOs) and urban flooding | Decentralized control strategy for multi-agent reinforcement learning |

| (Chang et al., 2018) [127] | Development of wireless water level monitoring system for urban drainage floods | Pressure Sensor |

| (Peleg et al., 2023) [130] | Low-cost acoustic sensor detects rainfall | Low-cost acoustic sensor, short-term early warning |

| (Hong & Shi, 2023) [135] | Integrating heterogeneous sensor systems to provide disaster information to stakeholders | Multiple data fusion |

| (R.-Q. Wang et al., 2018) [137] | High-resolution monitoring of urban flooding using social media and crowdsourced data | Natural language processing; computer vision; |

| (H. Han et al., 2021) [133] | Automatic monitoring method for urban road flooding | YOLOv2 |

| (J. Zhao et al., 2024) [123] | Optimizing the spatial layout of impervious surfaces | Nondominated Sorting Genetic algorithm 2 (NSGA2), and Multiple Linear Programming (MLP) algorithm |

5.4.2. Challenges and Opportunities

5.5. Other Research on Urban Flood Disaster Management

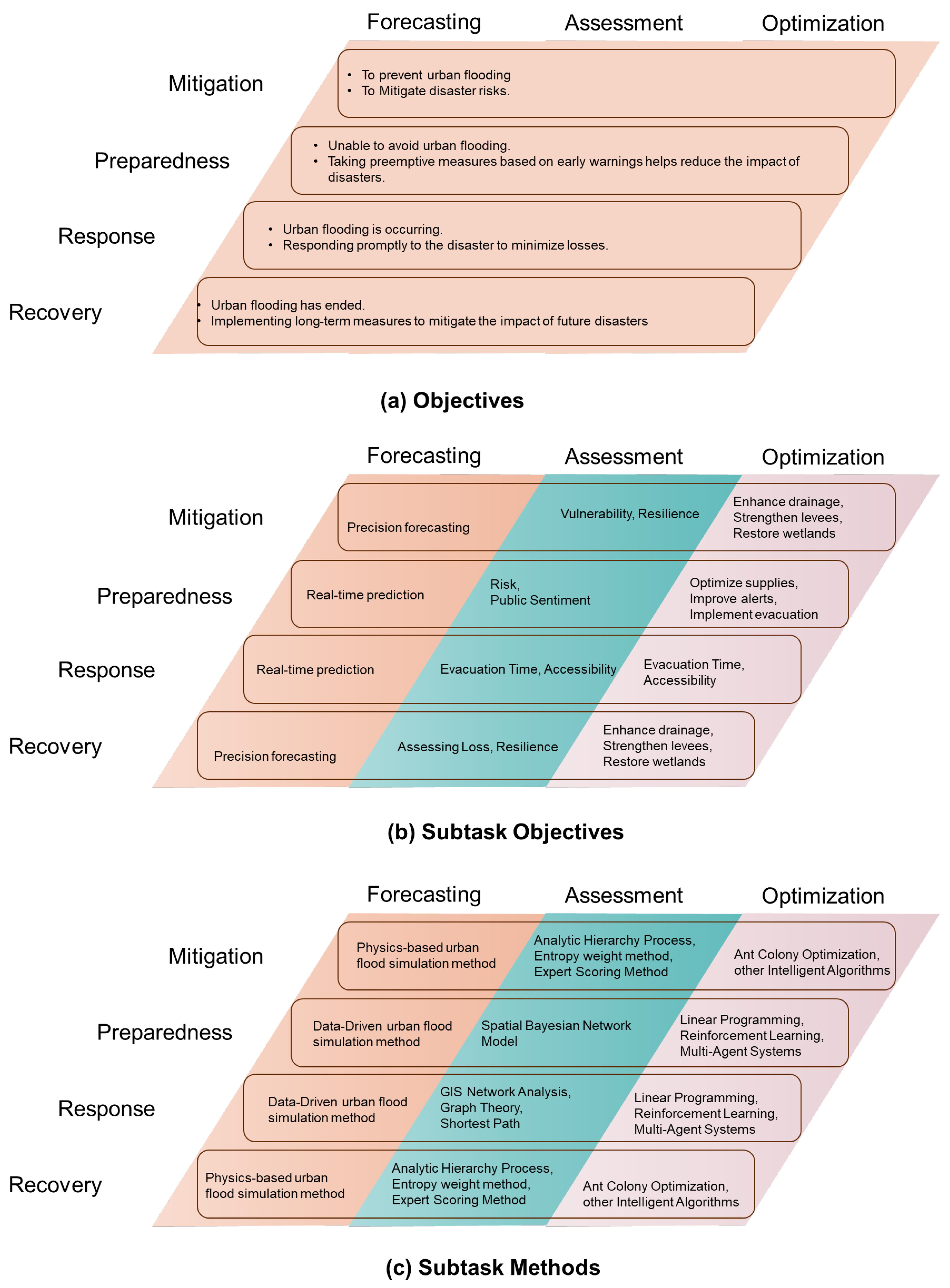

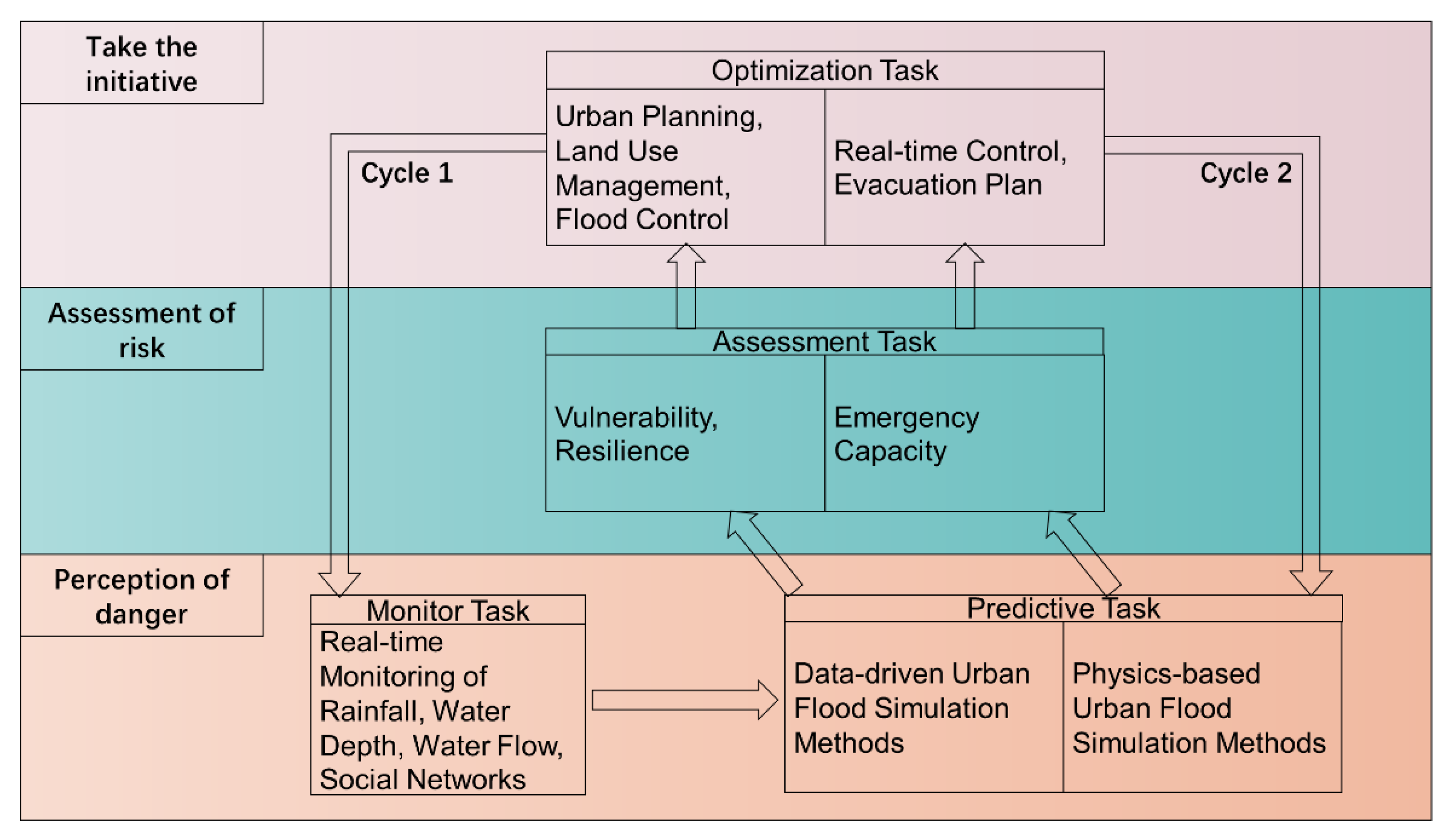

6. Research Framework for Urban Flood Disaster

6.1. Three Subtasks in Urban Flood Disaster Management

6.2. The Relationship Between Prediction, Evaluation, and Optimization

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Prediction

- (2)

- Evaluation

- (3)

- Optimization

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICFM. A Compilation of 2020–2021 Global Flood Events and International Experience in Flood Management—Reports—Views—ICFM—International Conference on Flood Management. 2022. Available online: https://www.icfm.world/Views/Reports/874/A-COMPILATION-OF-2020-2021-GLOBAL-FLOOD-EVENTS-AND-INTERNATIONAL-EXPERIENCE-IN-FLOOD-MANAGEMENT (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Zang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Guan, X.; Lv, H.; Yan, D. Study on urban flood early warning system considering flood loss. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2025: Resilience Pays: Financing and Investing for Our Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, P.; Yang, W.; Qi, X.; Jiang, S.; Xie, J.; Gu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Krebs, P. Evaluating the effect of urban flooding reduction strategies in response to design rainfall and low impact development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Scheffran, J.; Qin, H.; You, Q. Climate-related flood risks and urban responses in the Pearl River Delta, China. Reg. Environ. Change 2015, 15, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, T.W.; Sanders, B.F.; Flick, R.E. Urban coastal flood prediction: Integrating wave overtopping, flood defenses and drainage. Coast. Eng. 2014, 91, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, T.W.; Schubert, J.E.; Sanders, B.F. Predicting tidal flooding of urbanized embayments: A modeling framework and data requirements. Coast. Eng. 2011, 58, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.-C.; Jung, H.-S.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S. Spatial prediction of flood susceptibility using random-forest and boosted-tree models in Seoul metropolitan city, Korea. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, J.E.; Sanders, B.F. Building treatments for urban flood inundation models and implications for predictive skill and modeling efficiency. Adv. Water Resour. 2012, 41, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.M.; Balmforth, D.J.; Saul, A.J.; Blanskby, J.D. Flooding in the future—Predicting climate change, risks and responses in urban areas. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 52, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z. Depth prediction of urban flood under different rainfall return periods based on deep learning and data warehouse. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Research on urban waterlogging risk prediction based on the coupling of the BP neural network and SWMM model. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 3417–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.F.; Miguez, M.G. Supporting decision-making on urban flood control alternatives through a recovery deficit procedure for successive events. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipovic, N.; Viergutz, K. Smart Solutions for Municipal Flood Management: Overview of Literature, Trends, and Applications in German Cities. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, N.; Lu, Y.; Guo, B.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Yao, Y. Review on Urban Flood Risk Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battemarco, B.P.; Veról, A.P.; Miguez, M.G. Methodological framework for quantitative assessment of urban development projects considering flood risks and city responses. Urban Water J. 2023, 20, 1695–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhao, X.; Qi, X.; Cai, R. Vulnerability assessment and future prediction of urban waterlogging—A case study of Fuzhou. Water 2023, 15, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Muhammad Adnan Ikram, R.; Su, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Matrix scenario-based urban flooding damage prediction via convolutional neural network. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Mitani, Y.; Kawano, K.; Taniguchi, H.; Honda, H.; Meng, L.; Li, Z. Quantitative assessment of flooding risk based on predicted evacuation time: A case study in Joso city, Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 98, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.-S.; Kuo, P.-H.; Lai, J.-S. A nonstructural flood prevention measure for mitigating urban inundation impacts along with river flooding effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz Barcellos Pda, C.; da Costa, M.S.; Cataldi, M.; Soares, C.A.P. Management of non-structural measures in the prevention of flash floods: A case study in the city of Duque de Caxias, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Nat. Hazards 2017, 89, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Ju, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, D. Predicting and improving the waterlogging resilience of urban communities in China—A case study of Nanjing. Buildings 2022, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, Y. Optimization of impervious surface space layout for prevention of urban rainstorm waterlogging: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, S.; Shrestha, S.; Ninsawat, S.; Chonwattana, S. Predicting flood events in Kathmandu Metropolitan City under climate change and urbanisation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Huang, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Urban inundation response to rainstorm patterns with a coupled hydrodynamic model: A case study in Haidian Island, China. J. Hydrol. 2018, 564, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojinović, Z. Flood Risk: The Holistic Perspective: From Integrated to Interactive Planning for Flood Resilience; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.H. Catastrophe and Social Change: Based upon a Sociologicalstudy of the Halifax Disaster; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, S.; Wallace, W.A. The Emerging Area Of Emergency Management and Engineering. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1998, 45, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.M. Reconsidering the Phases of Disaster. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 1997, 15, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, D. A framework for integrated emergency management. Public Adm. Rev. 1985, 45, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A. Towards an Explanation and Reduction of Disaster Proneness; Bradford University, Disaster Research Unit: Bradford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D. Principles of Emergency Planning and Management. 2002. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Principles-of-Emergency-Planning-and-Management-Alexander/8fbad752582b17814ac0f44a77aa6f8ebaa4de1f (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Coetzee, C.; Van Niekerk, D. Tracking the evolution of the disaster management cycle: A general system theory approach. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2012, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, N.; Green, W.G. OR/MS research in disaster operations management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 175, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, G.; Batta, R. Review of recent developments in OR/MS research in disaster operations management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 230, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamos Díaz, H.; Aguilar Imitola, K.; Acosta Amado, R.J. OR/MS research perspectives in disaster operations management: A literature review. Rev. Fac. Ing. Univ. Antioq. 2019, 91, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntire, D. Disaster Response and Recovery: Strategies and Tactics for Resilience; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Disaster-Response-and-Recovery%3A-Strategies-and-for-McEntire/2b63cb4ac137487f387e3b672a735a9a18b54988 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Price, R.K.; Vojinovic, Z. Urban flood disaster management. Urban Water J. 2008, 5, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, N.N.M.; Hamidi, Z.S. Community-based approach for a flood preparedness plan in Malaysia. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2019, 11, a598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.S.H.; Ali, M.I.; Razi, P.Z.; Ramli, N.I. Flood Risk Management in Development Projects: A Review of Malaysian Perspective within the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Construction 2024, 4, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzamil, S.A.H.B.S.; Zainun, N.Y.; Ajman, N.N.; Sulaiman, N.; Khahro, S.H.; Rohani, M.M.; Mohd, S.M.B.; Ahmad, H. Proposed Framework for the Flood Disaster Management Cycle in Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Kumar, P.; Rana, N.P.; Islam, R.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Impact of internet of things (IoT) in disaster management: A task-technology fit perspective. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 759–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Pang, C.; Tang, H. Sensors on the Internet of Things Systems for Urban Disaster Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Tan, Y.; Deng, N. A Scientometric Review of Urban Disaster Resilience Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P. Characteristics, dimensions and methods of current assessment for urban resilience to climate-related disasters: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L.; Van Eck, N.J.; Noyons, E. A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. J. Infometr. 2010, 4, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, M.E.; Wu, X.B.; Whisenant, S.G. Bottomland hardwood forest species responses to flooding regimes along an urbanization gradient. Ecol. Eng. 2007, 29, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Biddulph, P.; Davies, M.; Man Lai, K. Predicting the microbial exposure risks in urban floods using GIS, building simulation, and microbial models. Environ. Int. 2013, 51, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratil, O.; Boukerb Ma Perret, F.; Breil, P.; Caurel, C.; Schmitt, L.; Lejot, J.; Petit, S.; Marjolet, L.; Cournoyer, B. Responses of streambed bacterial groups to cycles of low-flow and erosive floods in a small peri-urban stream. Ecohydrology 2020, 13, e2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.B.; Pham, H.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Giang, T.L.; Pham, T.P.N.; Nghiem, V.S.; Nguyen, D.H.; Vu, K.C.; Bui, Q.D.; Pham, H.N.; et al. Monitoring the effects of urbanization and flood hazards on sandy ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammar, A.; Abosuliman, S.S.; Rahaman, K.R. Social Capital and Disaster Resilience Nexus: A Study of Flash Flood Recovery in Jeddah City. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, N.; Liang, X.; Wan, S. An edge intelligence empowered flooding process prediction using Internet of things in smart city. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2022, 165, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M.M. Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. Am. Doc. 1963, 14, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhahn, S.; Fuchs, L.; Neuweiler, I. An ensemble neural network model for real-time prediction of urban floods. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Lamond, J.; Proverbs, D.; Bhattacharya-Mis, N.; Lopez, A.; Papachristodoulou, N.; Bird, A.; Bloch, R.; Davies, J.; Barker, R. Cities and Flooding: A Guide to Integrated Urban Flood Risk Management for the 21st Century; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, S.; Patidar, S.; Xia, X.; Liang, Q.; Neal, J.; Pender, G. A deep convolutional neural network model for rapid prediction of fluvial flood inundation. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.; Ntegeka, V.; Wolfs, V.; Willems, P. Development and Comparison of Two Fast Surrogate Models for Urban Pluvial Flood Simulations. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 2801–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, D.; Yu, D.; Wilby, R.L.; Green, D.; Herring, Z. Beyond ‘flood hotspots’: Modelling emergency service accessibility during flooding in York, UK. J. Hydrol. 2017, 546, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.W.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, D.; Yin, Z.; Liu, M.; He, Q. Evaluating the impact and risk of pluvial flash flood on intra-urban road network: A case study in the city center of Shanghai, China. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tajima, Y.; Sanuki, H.; Shibuo, Y.; Furumai, H. A novel approach for determining integrated water discharge from the ground surface to trunk sewer networks for fast prediction of urban floods. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2022, 15, e12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.E.; Scheffran, J.; Süsser, D.; Dawson, R.; Chen, Y.D. Assessment of Flood Losses with Household Responses: Agent-Based Simulation in an Urban Catchment Area. Environ. Model. Assess. 2018, 23, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Smith, J.A.; Baeck, M.L.; Zhang, Y. Flash flooding in small urban watersheds: Storm event hydrologic response. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 4571–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Study of Urban Flooding Response under Superstandard Conditions. Water 2023, 15, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Lyu, J.; Pan, Z.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.; Yu, G.; Tang, J. Urban rainfall-runoff flooding response for development activities in new urbanized areas based on a novel distributed coupled model. Urban Clim. 2023, 51, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Xiao, L.; Li, X.; Mei, Y.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Chen, X. A study on compound flood prediction and inundation simulation under future scenarios in a coastal city. J. Hydrol. 2024, 628, 130475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Miller, A.J.; Baeck, M.L.; Nelson, P.A.; Fisher, G.T.; Meierdiercks, K.L. Extraordinary Flood Response of a Small Urban Watershed to Short-Duration Convective Rainfall. J. Hydrometeorol. 2005, 6, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieeinasab, A.; Norouzi, A.; Kim, S.; Habibi, H.; Nazari, B.; Seo, D.-J.; Lee, H.; Cosgrove, B.; Cui, Z. Toward high-resolution flash flood prediction in large urban areas—Analysis of sensitivity to spatiotemporal resolution of rainfall input and hydrologic modeling. J. Hydrol. 2015, 531, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-S. Adaptive Blending Method of Radar-Based and Numerical Weather Prediction QPFs for Urban Flood Forecasting. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndahl, S.; Nielsen, J.E.; Jensen, D.G. Urban pluvial flood prediction: A case study evaluating radar rainfall nowcasts and numerical weather prediction models as model inputs. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 2599–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, H.; Yang, D.; Shi, B.; Ma, Y.; Ji, G. High-resolution simulation and monitoring of urban flood processes at the campus scale. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2021, 26, 05021018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Huo, A.; Liu, Q.; Yang, L.; Luo, C.; Ahmed, A.; Elbeltagi, A. Assessment of urban inundation and prediction of combined flood disaster in the middle reaches of Yellow river basin under extreme precipitation. J. Hydrol. 2024, 640, 131707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.-Y.; Pan, T.-Y.; Chang, H.-K.; Hsieh, C.-T.; Lai, J.-S.; Tan, Y.-C.; Su, M.-D. Using Tabu Search Adjusted with Urban Sewer Flood Simulation to Improve Pluvial Flood Warning via Rainfall Thresholds. Water 2019, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, J.; Pan, Z.; Li, B.; Jing, J.; Shen, J. Responses of urban flood processes to local land use using a high-resolution numeric model. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Dajun, Z.; Duan, Y.; Xu, X. Exploring the typhoon intensity forecasting through integrating AI weather forecasting with regional numerical weather model. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krvavica, N.; Rubinić, J. Evaluation of Design Storms and Critical Rainfall Durations for Flood Prediction in Partially Urbanized Catchments. Water 2020, 12, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Ma, C.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, K.; Han, H. A review on applications of urban flood models in flood mitigation strategies. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyls, D.M.; Thorndahl, S.; Rasmussen, M.R. Return period assessment of urban pluvial floods through modelling of rainfall–flood response. J. Hydroinform. 2018, 20, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, T.J.; Neal, J.C.; Bates, P.D.; Harrison, P.J. Geometric and structural river channel complexity and the prediction of urban inundation. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 3173–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, A.W.Z.; He, R.; Zhang, L. Multiscale homogenized predictive modelling of flooding surface in urban cities using physics-induced deep AI with UPC. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Han, K.Y. Urban Flood Prediction Using Deep Neural Network with Data Augmentation. Water 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Leitão, J.P.; Simões, N.E.; Moosavi, V. Data-driven flood emulation: Speeding up urban flood predictions by deep convolutional neural networks. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Han, Z.; Xu, H.; Bin, L. Rapid Prediction Model for Urban Floods Based on a Light Gradient Boosting Machine Approach and Hydrological–Hydraulic Model. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Bae, D.-H. Correcting mean areal precipitation forecasts to improve urban flooding predictions by using long short-term memory network. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Fast Prediction of Urban Flooding Water Depth Based on CNN−LSTM. Water 2023, 15, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Simulated annealing algorithm optimized GRU neural network for urban rainfall-inundation prediction. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 1358–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahura, F.T.; Goodall, J.L.; Sadler, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Morsy, M.M.; Behl, M. Training machine learning surrogate models from a high-fidelity physics-based model: Application for real-Time street-scale flood prediction in an urban coastal community. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR027038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, A.E.; Scheidegger, A.; Banasik, K.; Rieckermann, J. Bayesian uncertainty assessment of flood predictions in ungauged urban basins for conceptual rainfall-runoff models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 1221–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, S.; van de Giesen, N.C.; ten Veldhuis, J.A.E. Can urban pluvial flooding be predicted by open spatial data and weather data? Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 85, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Willems, P. A Hybrid Model for Fast and Probabilistic Urban Pluvial Flood Prediction. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Guan, X.; Meng, Y.; Xu, H. Urban Flood Depth Prediction and Visualization Based on the XGBoost-SHAP Model. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 39, 1353–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Xu, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, T.; Ma, C. Rapid prediction of urban flood based on disaster-breeding environment clustering and Bayesian optimized deep learning model in the coastal city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, R.; Böhm, J.; Jensen, D.G.; Leandro, J.; Rasmussen, S.H. U-FLOOD—Topographic deep learning for predicting urban pluvial flood water depth. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, M.; Zhao, G.; Wu, W.; Yue, Q. A Convolutional Neural Network-Weighted Cellular Automaton Model for the Fast Prediction of Urban Pluvial Flooding Processes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2024, 15, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Li, Z.; Xia, Y.; Song, S. An effective rainfall–ponding multi-Step prediction model based on LSTM for urban waterlogging points. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, T.; Yu, T.; Chu, S. Advancing rapid urban flood prediction: A spatiotemporal deep learning approach with uneven rainfall and attention mechanism. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, H.; Mao, J.; Cao, X.; Fu, G. High temporal resolution urban flood prediction using attention-based LSTM models. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jian, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Urban waterlogging prediction and risk analysis based on rainfall time series features: A case study of Shenzhen. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1131954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Lago, C.A.F.; Giacomoni, M.H.; Bentivoglio, R.; Taormina, R.; Gomes, M.N.; Mendiondo, E.M. Generalizing rapid flood predictions to unseen urban catchments with conditional generative adversarial networks. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, H.; Yan, D.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Adaptive selection and optimal combination scheme of candidate models for real-time integrated prediction of urban flood. J. Hydrol. 2023, 626, 130152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T. Urban flood prediction based on PCSWMM and stacking integrated learning model. Nat. Hazards 2024, 121, 1971–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Kong, N.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, X. Spatial Accessibility Assessment of Emergency Response of Urban Public Services in the Context of Pluvial Flooding Scenarios: The Case of Jiaozuo Urban Area, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, R.; Sole, A.; Adamowski, J.; Mancusi, L. A GIS-based model to estimate flood consequences and the degree of accessibility and operability of strategic emergency response structures in urban areas. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 2847–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, H.A.; Schubert, J.E.; Sanders, B.F. Structural Damage Prediction in a High-Velocity Urban Dam-Break Flood: Field-Scale Assessment of Predictive Skill. J. Eng. Mech. 2012, 138, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, D.; Liao, B. A city-scale assessment of emergency response accessibility to vulnerable populations and facilities under normal and pluvial flood conditions for Shanghai, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 2239–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwal, U.; Dong, S. Critical facility accessibility rapid failure early-warning detection and redundancy mapping in urban flooding. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 224, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Hartmann, J.; Li, K.W.; An, Y.; Asgary, A. Multi-Criteria Decision Support Systems for Flood Hazard Mitigation and Emergency Response in Urban Watersheds1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2007, 43, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Du, G.; Zhou, J. Urban flood risk warning under rapid urbanization. Environ. Res. 2015, 139, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Lu, L.; Li, Y.; Hong, Y. A Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response study for urban transport resilience under extreme rainfall-flood conditions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Newman, G. Advancing scenario planning through integrating urban growth prediction with future flood risk models. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 82, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbi, S.; Villa, F.; Mojtahed, V.; Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Giupponi, C. A spatial Bayesian network model to assess the benefits of early warning for urban flood risk to people. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Loo, B.P.Y.; Zhen, F.; Xi, G. Urban resilience from the lens of social media data: Responses to urban flooding in Nanjing, China. Cities 2020, 106, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Kong, N.; Li, X.; Zhou, X. Evaluation of Emergency Response Capacity of Urban Pluvial Flooding Public Service Based on Scenario Simulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, J.; Yong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Q.; Hao, J.; et al. Dynamic response of flood risk in urban-township complex to future uncertainty. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, J.P.J.; Costa, D.G.; Portugal, P.; Vasques, F. Flood-Resilient Smart Cities: A Data-Driven Risk Assessment Approach Based on Geographical Risks and Emergency Response Infrastructure. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, D.; Lin, N.; Wilby, R.L. Evaluating the cascading impacts of sea level rise and coastal flooding on emergency response spatial accessibility in Lower Manhattan, New York City. J. Hydrol. 2017, 555, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xie, T.; Yu, Q.; Niu, C.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Q.; Hu, C. Study on the response analysis of LID hydrological process to rainfall pattern based on framework for dynamic simulation of urban floods. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ke, E.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y. An optimization model for the impervious surface spatial layout considering differences in hydrological unit conditions for urban waterlogging prevention in urban renewal. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, G.; Assaad, R.H. Optimal Preventive Maintenance, Repair, and Replacement Program for Catch Basins to Reduce Urban Flooding: Integrating Agent-Based Modeling and Monte Carlo Simulation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xia, J.; She, D.; Guo, Q.; Su, Y.; Wang, W. Integrated intra-storm predictive analysis and real-time control for urban stormwater storage to reduce flooding risk in cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, W.; Liao, Z. Towards coordinated and robust real-time control: A decentralized approach for combined sewer overflow and urban flooding reduction based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-K.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lai, J.-S. Methodology to set trigger levels in an urban drainage flood warning system—An application to Jhonghe, Taiwan. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Coll, M.; Ballester-Merelo, F.; Martínez-Peiró, M. Early warning system for detection of urban pluvial flooding hazard levels in an ungauged basin. Nat. Hazards 2018, 92, 1237–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.-J.; Jung, I. Development of High-Precision Urban Flood-Monitoring Technology for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sensors 2023, 23, 9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, N.; Torelló-Sentelles, H.; Mariéthoz, G.; Benoit, L.; Leitão, J.P.; Marra, F. Brief communication: The potential use of low-cost acoustic sensors to detect rainfall for short-term urban flood warnings. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Sobral, V.A.; Nelson, J.; Asmare, L.; Mahmood, A.; Mitchell, G.; Tenkorang, K.; Todd, C.; Campbell, B.; Goodall, J.L. A Cloud-Based Data Storage and Visualization Tool for Smart City IoT: Flood Warning as an Example Application. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaya, R.; Kanthavel, R. Video Surveillance-Based Urban Flood Monitoring System Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2021, 32, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hou, J.; Bai, G.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Gao, X.; Su, F.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Q.; et al. A deep learning technique-based automatic monitoring method for experimental urban road inundation. J. Hydroinform. 2021, 23, 764–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.-W.; Wu, J.-H.; Lin, F.-P.; Hsu, C.-H. Visual Sensing for Urban Flood Monitoring. Sensors 2015, 15, 20006–20029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.-H.; Shi, Y.-T. Integration of Heterogeneous Sensor Systems for Disaster Responses in Smart Cities: Flooding as an Example. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Willems, P. Probabilistic flood prediction for urban sub-catchments using sewer models combined with logistic regression models. Urban Water J. 2019, 16, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-Q.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Rae, C.; Shaw, W. Hyper-resolution monitoring of urban flooding with social media and crowdsourcing data. Comput. Geosci. 2018, 111, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, F.; Tong, J. Online urban-waterlogging monitoring based on a recurrent neural network for classification of microblogging text. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Mostafavi, A. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks for road network inundation status prediction during urban flooding. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 97, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Liu, X. Spatiotemporal information mining for emergency response of urban flood based on social media and remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lee, H.; Kang, D.; Kim, B.; Park, M. A Study on the Determination Methods of Monitoring Point for Inundation Damage in Urban Area Using UAV and Hydrological Modeling. Water 2022, 14, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.K.; Karvonen, A. Climate governance at the fringes: Peri-urban flooding drivers and responses. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Establishing a risk dynamic evolution model to predict and solve the problem of urban flood disaster. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 53522–53539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, A.B.; Davies, J.B.; Black, S.L. A CGE Framework for Modeling the Economics of Flooding and Recovery in a Major Urban Area. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 1314–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, B.; Sinha, P.K. An ontological data model to support urban flood disaster response. J. Inf. Sci. 2023, 51, 01655515231167297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, X. A full-view scenario model for urban waterlogging response in a big data environment. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 1432–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shen, J.; Zang, K.; Shi, X.; Du, Y.; Šilhák, P. Spatio-Temporal Visualization Method for Urban Waterlogging Warning Based on Dynamic Grading. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.; Wolfe, S.E. Risk Perceptions and Terror Management Theory: Assessing Public Responses to Urban Flooding in Toronto, Canada. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Smith, S.R.; Wright, C.; Buchhorn, Y.M.; Peden, A.E. Predicting and Changing Intentions to Avoid Driving into Urban Flash Flooding. Water 2022, 14, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.B.; Vallimeena, P.; Gopalakrishnan, U.; Rao, S.N.; Krishnamoorthy, S. Enhanced Urban Flood Monitoring: Integrating Advanced Semantic Segmentation and Human Facial Feature and Posture Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 185807–185825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, K.; Yang, M.; Man, K.L.; Kim, M. Crowd-movement-based Geofence-construction method for urban flood response. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2024, 18, 3470–3490. [Google Scholar]

| Stages | Objectives | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Mitigation | Preventing the occurrence of disasters and mitigating their impacts. | Prevent |

| Low impact development | ||

| Sponge City | ||

| Preparedness | Providing early warning and monitoring of disasters to reduce their impact. | Predict |

| Monitor | ||

| Warn | ||

| Response | Taking swift action to address emergencies when disasters occur. | Emergency supply |

| Response | ||

| Control | ||

| Decision | ||

| Coordinate | ||

| Recovery | Implementing long-term measures to mitigate the impact of future disasters. | Recovery |

| Restoration | ||

| Reconstruction |

| List | Keyword |

|---|---|

| List1-Geographical Scope | urban, city, cities |

| List2-Disaster Type | flood, waterlogging, inundation |

| List3-Disaster Management Methods | prevent, predict, monitor, warn, response, recovery |

| Exclusion Criteria | Number of Exclusions |

|---|---|

| Review Articles | 36 |

| unrelated to urban flooding | 6 |

| focusing on regional areas | 88 |

| Title | Cluster | Total Link Strength | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| An ensemble neural network model for real-time prediction of urban floods (Berkhahn et al., 2019) [57] | 1 | 46 | 12 |

| Depth prediction of urban flood under different rainfall return periods based on deep learning and data warehouse (Z. Wu et al., 2020) [12] | 1 | 33 | 12 |

| Cities and Flooding: A guide to integrated urban flood risk management for the 21st Century (Jha et al., 2012) [58] | 1 | 14 | 9 |

| A deep convolutional neural network model for rapid prediction of fluvial flood inundation (Kabir et al., 2020) [59] | 1 | 28 | 8 |

| Development and Comparison of Two Fast Surrogate Models for Urban Pluvial Flood Simulations (Bermúdez et al., 2018) [60] | 1 | 27 | 7 |

| Beyond ‘flood hotspots’: Modelling emergency service accessibility during flooding in York, UK (Coles et al., 2017) [61] | 2 | 12 | 7 |

| River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I-A discussion of principles (Nash & Sutcliffe, 1970) [62] | 1 | 19 | 7 |

| Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis (Teng et al., 2017) [63] | 1 | 24 | 7 |

| Evaluating the impact and risk of pluvial flash flood on intra-urban road network: A case study in the city center of Shanghai, China (Yin et al., 2016) [64] | 2 | 15 | 7 |

| Label | Cluster | Total Link Strength | Occurrences | Avg. Pub. Year | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flood | 3 | 130 | 46 | 2019 | 25.76 |

| model | 3 | 105 | 30 | 2020 | 26.53 |

| risk | 1 | 125 | 29 | 2019 | 27.03 |

| impact | 1 | 92 | 27 | 2020 | 23.33 |

| rainfall | 4 | 81 | 22 | 2020 | 20.59 |

| simulation | 3 | 71 | 18 | 2020 | 27.11 |

| management | 1 | 68 | 18 | 2020 | 20.94 |

| climate change | 1 | 50 | 15 | 2019 | 32.00 |

| neural network | 2 | 39 | 14 | 2022 | 10.07 |

| inundation | 2 | 46 | 13 | 2020 | 37.31 |

| hydraulic model | 3 | 35 | 11 | 2018 | 41.27 |

| vulnerability | 1 | 44 | 11 | 2020 | 20.18 |

| prediction | 2 | 32 | 11 | 2021 | 14.64 |

| assessment | 1 | 28 | 9 | 2017 | 41.67 |

| waterlogging | 2 | 23 | 9 | 2022 | 8.00 |

| drainage system | 3 | 35 | 8 | 2019 | 37.13 |

| resilience | 1 | 32 | 8 | 2020 | 25.88 |

| pluvial flood | 1 | 46 | 8 | 2021 | 18.88 |

| city | 1 | 34 | 8 | 2022 | 14.00 |

| precipitation | 4 | 22 | 7 | 2017 | 26.86 |

| machine learning | 2 | 27 | 7 | 2022 | 14.86 |

| Research Dimensions | Current Research Themes | Research Challenges and Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Physics-based models for urban flood simulation | Fundamental model development Integration of multiple models to account for diverse flood factors Applications include designing urban flood control schemes and early warning systems | Striking a balance between computational speed and precision Enhancing model versatility and portability Integration with digital twin technology |

| 2 Data-driven models for urban flood simulation | Rapid forecasting Real-time prediction | Striking a balance between computational speed and precision Addressing the ongoing challenges unique to data-driven approaches, including managing large volumes of data, ensuring model interpretability, and mitigating risks of overfitting Innovative integration methods for combining data-driven models |

| 3 Risk assessment tasks for urban flood disaster management | Diverse entities: cities, urban subsystems, communities, families, individuals, and programs Aspects: emergency response capabilities, disaster losses, vulnerability, resilience, and risk. | Establishing a unified evaluation index system Formulating standardized loss quantification methods Accounting for the disaster’s dynamic nature Broadening the scope of evaluation tasks in both temporal and spatial dimensions |

| 4 Optimization tasks of urban flood disaster management | Monitoring: rainfall, water level, water area, network data Optimization: land use, maintenance strategies, real-time control of drainage pipes | Building a disaster early warning system based on multi-source data fusion Optimization framework integrating knowledge from multiple subject areas |

| Research Objectives | Representative Papers |

|---|---|

| Predicting urban flooding using single-value output | Presenting an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) based model for the prediction of maximum water levels during a flash flood event (Berkhahn et al., 2019) [57] Developing an ANN model to predict cumulative overflow volumes, based on simulation results generated by SWMM (H. I. Kim & Han, 2020) [86] Presenting a CNN model for the prediction of maximum water levels (Guo et al., 2021) [87] Presenting a Gradient Boosted Decision Tree for predicting flood depth (Z. Wu et al., 2020) [12] Developing a Light Gradient Boosting Machine model to predict maximum depth, based on simulation results generated by PCSWMM (K. Xu et al., 2023) [88] |

| Predicting time series of urban flooding | Presenting a LSTM model for generating three-hour urban flooding predictions (Nguyen & Bae, 2020) [89] Using CNN and LSTM to predict urban flood depth (J. Chen, Li et al., 2023) [90] Employing a GRU model optimized via simulated annealing for hourly urban rainfall-inundation depth prediction (Yan et al., 2023) [91] |

| Evaluation Methods | Research Topic and Representative Papers |

|---|---|

| Entropy weight method | Evaluating urban public service emergency response capabilities (Y. Zhang, Li et al., 2022) [107] Predicting regional water accumulation risks under different urban heavy rain scenarios (J. Zhang, Li et al., 2023) [13] Assessing Fuzhou’s vulnerability and predict its future development (X. Wang et al., 2023) [18] |

| Depth-destruction function | Estimating direct and indirect losses during flood events in urban areas (Albano et al., 2014) [108] Comprehensive assessment of economic losses (H. Yuan et al., 2024) [19] Analysis of successive flood events for recoverability (Guimarães & Miguez, 2020) [14] Examining the various damage states (Gallegos et al., 2012) [109] |

| Dijkstra shortest path | Quantifying evacuation risk in terms of evacuation time (Z. Han et al., 2023) [20] Assessing the spatial accessibility of emergency response to key public services in cities (Y. Zhang, Li et al., 2022) [107] Optimizing the distribution of emergency stations and developing strategic emergency plans for vulnerable populations and facilities (Yin et al., 2021) [110] |

| Graph theory | Reveal accessibility disparities and identify vulnerable communities (Gangwal & Dong, 2022) [111] |

| Expert scoring method | Predicting social, physical and economic resilience before floods occur (Cui et al., 2022) [23] |

| Analytic hierarchy process | Flood disaster mitigation and emergency response in urban watersheds (Levy et al., 2007) [112] Evaluating the performance of LID practices in urban flood control and emission reduction (Hua et al., 2020) [5] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, X.; Du, J.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, B.; Hu, M. Systematic Review for Urban Flood Disaster in Managerial Perspective: Forecasting, Assessment and Optimization. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021106

Tang X, Du J, Zhou H, Hu Z, Liu B, Hu M. Systematic Review for Urban Flood Disaster in Managerial Perspective: Forecasting, Assessment and Optimization. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021106

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Xuan, Juan Du, Hao Zhou, Zeqian Hu, Bing Liu, and Min Hu. 2026. "Systematic Review for Urban Flood Disaster in Managerial Perspective: Forecasting, Assessment and Optimization" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021106

APA StyleTang, X., Du, J., Zhou, H., Hu, Z., Liu, B., & Hu, M. (2026). Systematic Review for Urban Flood Disaster in Managerial Perspective: Forecasting, Assessment and Optimization. Sustainability, 18(2), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021106