4.1. The Coupling Coordination Degree Between GF and GTI

As shown in

Table 4, the CCD between GF and GTI across provinces in China presents an overall trend of “phased growth followed by a slight decline in the final period”. From 2010 to 2022, the coupling coordination degree of the vast majority of provinces showed a steady upward trend, reflecting the gradual improvement of China’s green finance system, the continuous enhancement of green technology innovation capabilities, and the constant optimization of the synergistic development mechanism between the two over the last decade and more.

Beijing has consistently maintained the highest coupling coordination degree nationwide, significantly outperforming other provinces. This is attributed to its multiple advantages as a national financial management center, a pioneer pilot zone for green policies, and an agglomeration of high-tech industries, boasting the optimal allocation efficiency of green financial resources and technological innovation factors. Relying on its status as an international financial center and the construction of a science and technology innovation center, Shanghai has long remained in second place.

For central provinces (Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, and Jiangxi), their coupling coordination degree generally ranges from 0.300 to 0.420, indicating that driven by the “dual carbon” goals, the supporting role of green finance for technological innovation in the central region has gradually come to the fore. Western provinces (Guizhou, Guangxi, and Xinjiang) have long had a coupling coordination degree below 0.300, falling into the category of regions with a low level of synergy. This reflects the constraints of scarce financial resources and a weak foundation for technological innovation in underdeveloped western areas.

Henan, however, exhibits special fluctuating characteristics, which may be related to the short-term impact of regional industrial structure transformation (such as the adjustment in the proportion of high-energy-consuming industries) regarding green synergy.

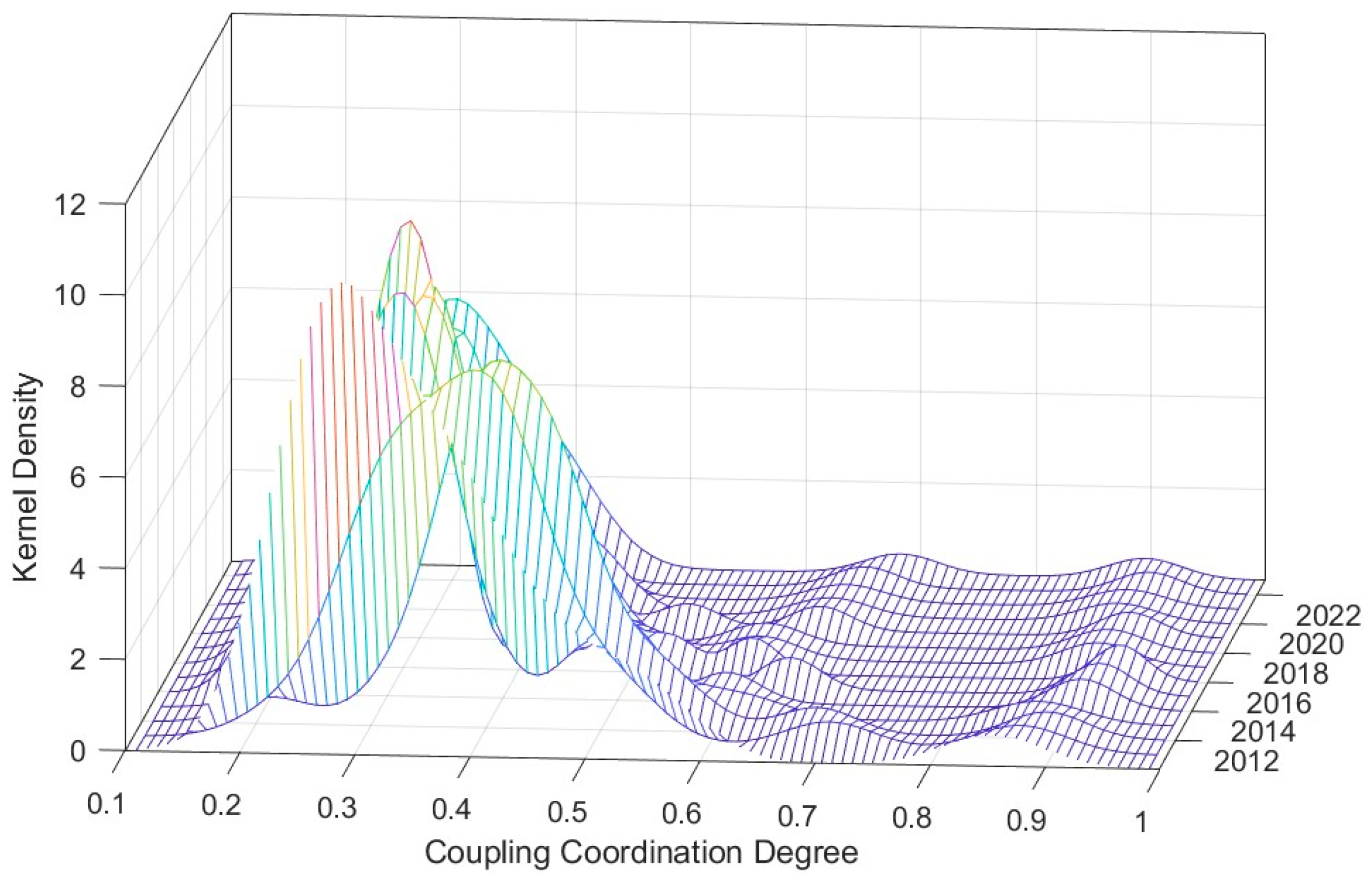

Figure 2 shows that the CCD between GF and GTI ranges from 0.25 to 0.39 and is generally in the stage of moderate imbalance. China’s current level of CCD between GF and GTI is not high [

15,

30]. Inter-regional differences are also relatively obvious; some regions are relatively backward in development level and have failed to achieve coordinated development.

From a temporal perspective, the CCD between GF and GTI was in a stage of fluctuating changes from 2010 to 2012. This is because national policies on green finance had not yet been introduced, the green finance development system was incomplete, and at the same time, enterprises had a low awareness of GTI. All of these factors became the main bottleneck restricting the improvement in the coordination degree [

14].

From 2013 to 2020, it entered a stage of rapid growth. The reason lies in the issuance of the Green Credit Guidelines in 2012 and the gradual improvement of green finance data. As the national green development strategy advanced in depth and the green finance policy was established, it entered a channel of rapid improvement [

41]. The two systems began to show positive interaction; however, in some regions, the development speed of GF lagged behind relative to the practice of GTI, which still restricted synergistic improvement.

After 2020, the growth rate of the CCD slowed down and even declined slightly. Affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, some green projects were hindered, the rhythm of green finance capital investment was disrupted, and green technology innovation activities were also suppressed by factors such as restrictions on personnel mobility and interruptions in the supply chain of key technology products. These factors, in turn, hindered the coordinated development process to a certain extent.

From a spatial perspective, the CCD between GF and GTI presents a distinct spatial distribution pattern. It has higher levels and faster development in the east, and lower levels and slower development in the west. Specifically, the CCD in eastern regions is significantly higher than the other two regions and is entering the stage of basic coordination. Eastern regions boast a more developed economy and obvious advantages in resource endowments such as geographical location, capital, and technology. The east’s GTI score is higher than the other two regions. In turn, GF holds advantages in industries and capital, forming a sound interactive cycle with GTI—thus resulting in a relatively high degree, which has increased from 0.29 to 0.47.

In recent years, the central region has achieved steady economic growth, with various economic indicators gradually improving. However, in the key field of GTI, there remains a notable gap between the central region and eastern China. Such gaps are reflected not only in the quantity and quality of innovative achievements and the R&D investment in green technologies but also in the promotion, application, and industrialization process of green technologies. Meanwhile, due to the lag in GTI, the central region also faces corresponding constraints in the development of GF: the scale and maturity of its green finance market are both inferior to those of eastern China. This prevents the CCD between GTI and GF in the central region from reaching the desired high level; instead, it remains at a medium level. Therefore, the central region is in urgent need of further resource input and policy support to narrow the gap with the eastern region and elevate the regional green economy’s overall development level [

30,

47].

Due to geographical constraints and economic limitations, the western region faces numerous challenges in the R&D, promotion, and application of green technologies, making it difficult to form a robust technological innovation system. Financial institutions have a low willingness to invest in green projects. Moreover, green financial products and services are relatively scarce. This creates obstacles to effectively meeting GTI’s capital needs. This leads to poor interaction between GF and GTI and a failure to form a sound synergistic effect between the two. Consequently, among the three regions, the western region has the lowest CCD between GF and GTI.

As shown in

Figure 3, the CCD of most provinces in China fell into the category of serious imbalance in 2010, while only a few provinces were at the levels of moderate imbalance and near imbalance. This is because the green finance system was still underdeveloped at that time, with limited financial support for GTI, and many innovation projects struggled to advance due to insufficient funds. Meanwhile, the market demand for GTI had not been fully stimulated, and enterprises lacked enthusiasm for conducting green technology R&D, resulting in a low output of GTI achievements. Additionally, policy guidance and incentive measures were insufficient, failing to effectively promote the in-depth integration and coordinated development between GF and GTI.

By 2016, the overall CCD had improved: most provinces had moved up to the moderate imbalance level, Jiangsu Province and Anhui Province reached the near imbalance level, and the Shanghai Municipality and Beijing Municipality took the lead in entering the excellent coordination level. This indicates that their GF systems and GTI systems had formed an efficient synergy mechanism. The reason lies in the gradual improvement of the green finance system during this period: the government increased support for green finance and introduced a series of incentive policies, and financial institutions also responded actively by providing more financial support for GTI projects, effectively promoting in-depth integration and coordinated development. Guided by the normative framework of green finance policies, financial institutions in the Shanghai Municipality, Beijing Municipality, Jiangsu Province, and Anhui Province continued to innovate green financial products and services. Simultaneously, these regions also established a sound green technology evaluation system, providing a basis for financial institutions to accurately identify and assess GTI projects. This further reduced the investment risks of financial institutions and enhanced their enthusiasm for participating in GTI.

In 2023, the coupling coordination level improved further, with the number of provinces at the serious imbalance level reducing to five, and Guangdong Province also advancing to the near imbalance level. This is attributed to the more mature development of green finance during this period: society’s awareness of and demand for green development increased significantly, and the market demand for green technology products became increasingly strong. This greatly stimulated enterprises’ enthusiasm for conducting green technology R&D and innovation, leading to a continuous emergence of GTI achievements, which further promoted the positive interaction and coordinated progress between GF and GTI. During this period, with strong support from local green finance policies, numerous enterprises in Guangdong Province had sufficient capital to increase investment in the green technology field and carry out a series of forward-looking and innovative R&D projects. Meanwhile, Guangdong’s sound industrial supporting system and abundant talent resources also created highly favorable conditions for GTI, thereby achieving rapid momentum in the coordinated development of the two systems.

4.4. Spatial Correlation Analysis

According to the First Law of Geography, the CCD may exhibit spatial correlation among adjacent regions. This study employs the spatial autocorrelation model and the high/low clustering model, taking the CCD as the measurement indicator, and uses ArcGIS 10.8 software to conduct a spatial correlation analysis on it.

Table 7 presents the Moran’s I index and its corresponding

p-value from 2010 to 2023. In most years (2011–2022), the Moran’s I index is significantly positive at the 5% significance level under the spatial weight matrix. This result indicates there is significant positive spatial correlation in the CCD. The spatial correlation reached its peak in 2016 (I = 0.3256) and showed a fluctuating downward trend thereafter. A possible reason for this is the intensive introduction of policies related to GF and GTI in China. In particular, in 2016, China issued the Guidelines for Establishing the Green Finance System, which clearly defined the definition and classification of green finance and proposed several specific measures to drive the growth of green finance [

11].

Figure 6 illustrates the high/low clustering distribution of the CCD between GF and GTI. The High-Low Outlier indicates that the attribute value of the research variable is relatively high, but the region is surrounded by areas with lower attribute values, showing a negative spatial correlation with the surrounding areas; the meanings of other clustering results are similar.

Through comparison, it can be found that the High-High Cluster is mainly concentrated in northern China. Adjacent provinces exhibit “neighboring imitation” in policy interpretation and the promotion of pilot experience. For example, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region jointly established a green technology trading market [

27]. These practices led to the simultaneous improvement of the CCD of adjacent provinces in these regions, forming a High-High Cluster, which ultimately manifests as a significant positive spatial correlation.

In addition, the spatial agglomeration characteristics of various provinces underwent significant changes in 2016. This may be attributed to the fact that the Chinese government promulgated the Guidelines for Establishing the Green Finance System, while provinces differed in the pace and intensity of policy implementation.

In general, the impact of each driving factor is not static but exhibits significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Policy formulation should abandon the “one-size-fits-all” paradigm and implement regionally differentiated, targeted strategies to promote coordinated regional development.

4.5. Analysis of Driving Factors

4.5.1. Model Selection and Validation

To verify the rationality of the model, the data on the CCD between GF and GTI were initially standardized. Subsequently, a multicollinearity test was conducted on each explanatory variable. The results show that the tolerance of each variable is greater than 0.1, and the VIF value is less than 1.680, indicating no multicollinearity. Thus, the next step of model construction can be carried out.

Following the diagnostic tests, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was performed on the driving factors. The results show that the OLS regression coefficients of all driving factors are significant at the 5% significance level, which indicates that economic development level, financial development level, population scale, and urbanization all have a significant positive impact on the CCD. Therefore, the selection of these four factors is meaningful.

Regarding the final model selection, the GTWR plugin in ArcGIS 10.8 software was used to conduct OLS, GWR, and GTWR analyses. As shown in

Table 8, GTWR results have a larger R

2, smaller Residual Sum of Squares (RSS), and smaller corrected AICc. Given that it exhibits the highest goodness of fit and the most obvious spatial heterogeneity, outperforming the OLS model and GWR model, this study selected the GTWR model to analyze the coupling development between GF and GTI in China’s provincial-level regions and its influencing factors.

4.5.2. Spatiotemporal Effects of Driving Factors

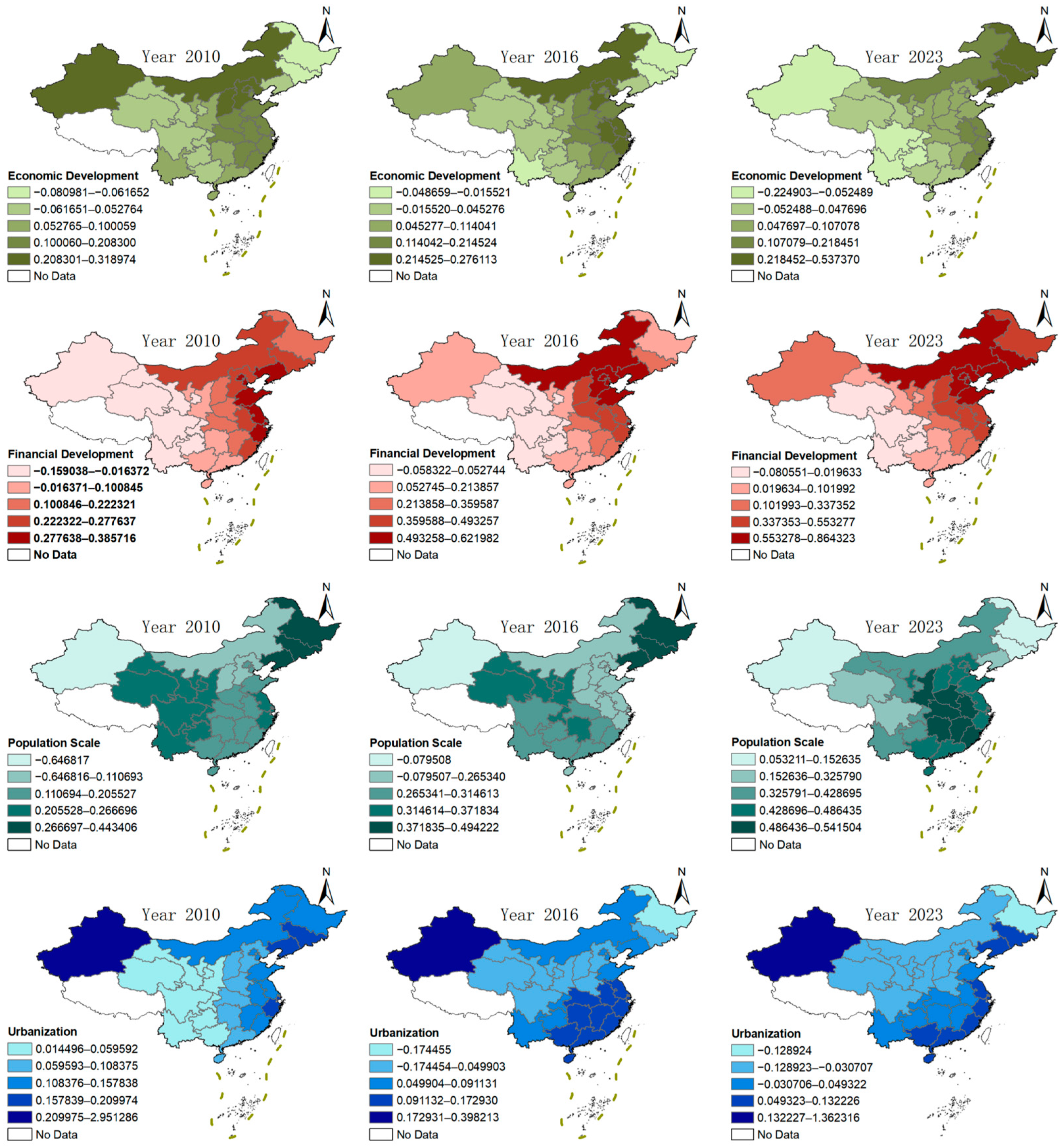

The economic development level (ED) is positively correlated with the CCD, as shown in

Figure 7, but it exhibits complex non-linearity and spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Economically developed eastern provinces have provided market demand and financial support for GTI through industrial structure upgrading and high-tech industry agglomeration. In contrast, economically underdeveloped western provinces are constrained by the low level of green finance development and the small scale of the financial market, resulting in a weak driving effect on GTI and even a negative regulatory effect in some local areas.

The financial development level (FD) has a significant positive impact on the CCD, with its regression coefficient being significant in most provinces and years, showing an obvious pattern of “higher levels and faster development in the east, and lower levels and slower development in the west”. This fully indicates that in eastern coastal areas, the abundance and allocation efficiency of financial resources directly determine the capital support for GTI R&D and transformation [

27], effectively promoting the R&D and industrialization of green technologies. However, in some central and western regions, the marginal contribution of financial development level is relatively low, which may be related to the uneven distribution of financial resources and insufficient coverage of green financial products.

The impact of population scale (PS) on the CCD presents a complex and changeable spatial pattern. Regions such as Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, which initially had high impact coefficients, have gradually evolved to a low level. This may be due to the economic recession, population outflow, or aging in northeast China in recent years. The population scale has a significant positive effect on the CCD in central China, with the highest effect in provinces such as Sichuan, Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi. This may be because China is promoting the transfer of coastal industries, and the resource potential and labor cost advantages of central China have begun to emerge. Therefore, when promoting green transformation, population factors must be incorporated into comprehensive considerations, and the potential pressure brought by population scale should be offset by improving resource utilization efficiency and advocating green lifestyles.

The impact of urbanization level (UR) on the CCD shows an obvious pattern of “higher in the east and lower in the west”. Highly urbanized regions (e.g., Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai) have promoted the in-depth integration of green technologies and urban construction through improved infrastructure, agglomeration of innovative resources, and policy pilot advantages, but their promoting effect tends to stabilize. In contrast, the urbanization process in western regions is still dominated by scale expansion, with insufficient capacity for green technology integration and application, leading to a weak driving effect. The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region shows strong particularities, which may be due to its large geographical area and single economic and industrial structure, but this does not affect the analysis results.

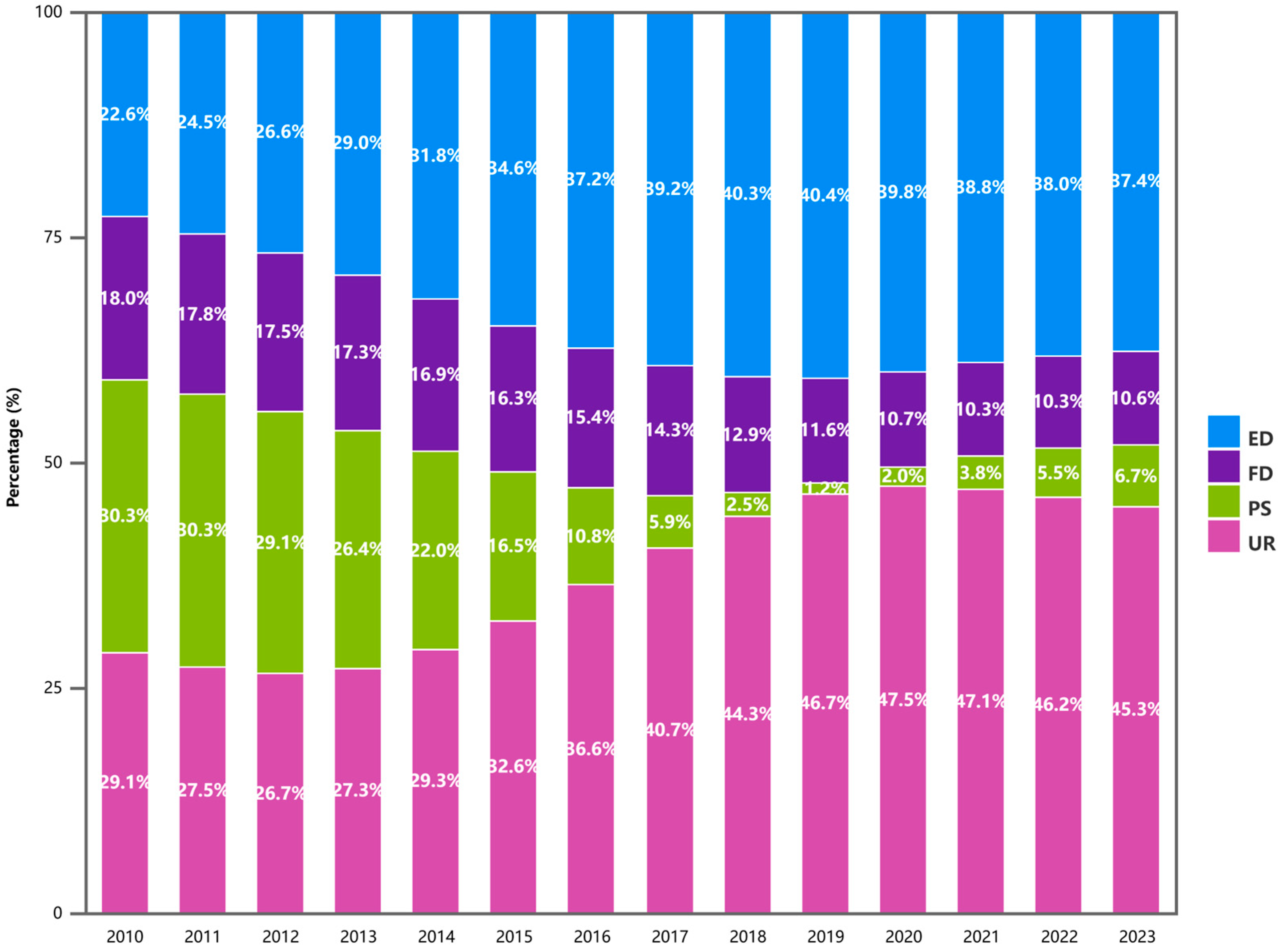

Figure 8 shows the average GTWR coefficients of each driving factor. The impact of economic development level and urbanization on the CCD between GF and GTI has been on an upward trend in each year. This indicates that by expanding the market scale and promoting population agglomeration, the diffusion of technology and industrial synergy have been accelerated, which provides stable financial support and demand-driven impetus for GTI, thus continuously strengthening the coupling coordination effect.

However, the impact of financial development level and population scale on the CCD between GF and GTI has shown a downward trend in each year. A possible reason lies in the dual effects of financial market saturation and policy adjustments. As the financial market gradually matures, the marginal contribution of green financial instruments decreases; in addition, tighter regulation in some regions has restrained innovation vitality. The negative impact of population scale, on the other hand, may be related to uneven resource allocation during the urbanization process, which weakens the scale effect. Concurrently, the environmental pressure caused by rapid urbanization has offset the positive contribution of the demographic dividend.

In general, the impact of each driving factor on the CCD between GF and GTI is not static but exhibits significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Policy formulation should implement differentiated and targeted regional coordination strategies.

4.6. Discussions

The empirical findings of this study are broadly consistent with, yet meaningfully extend, the existing literature on green finance and green technology innovation. Specifically, regarding the positive impact of green finance, Wang et al. [

7] demonstrated that green credit policies effectively reduce the R&D risks for enterprises, thereby stimulating patent output. Complementing this view, Liu et al. [

15] highlighted that diverse green financial instruments drive environmental performance by optimizing resource allocation in high-polluting sectors. Our results align with these observations, confirming that green finance acts as a vital catalyst for technological upgrading.

In terms of systemic interaction, recent research employing coupling coordination models has also documented similar trends. For instance, Chen et al. [

17] and Sun et al. [

30] observed moderate coordination levels and distinct regional disparities between green finance and digital technology. Consistent with these prior studies, our analysis reveals that while GF–GTI coupling has improved, it remains constrained by regional imbalances and structural bottlenecks.

However, this study advances the literature in several important respects. Most notably, compared with Zhao et al. [

41] and Chen et al. [

17], who mainly focus on static coupling levels or short time spans, this research provides a long-term (2010–2023) spatiotemporal analysis that reveals a three-stage evolution path and a post-2020 slowdown in coordination dynamics. This finding highlights the sensitivity of GF–GTI coordination to external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and global economic uncertainty.

Regarding regional imbalances, while prior studies often rely on overall inequality measures, this study employs the Dagum Gini coefficient decomposition to explicitly identify inter-regional disparity as the dominant source of imbalance. This decomposition-based evidence deepens the understanding of why national-level improvements may coexist with widening regional gaps.

Furthermore, by integrating spatial autocorrelation analysis and the GTWR model, this study uncovers significant spatial dependence and spatiotemporally heterogeneous driving mechanisms. Unlike conventional regression approaches that estimate average effects, the GTWR results demonstrate that the impacts of economic development, financial development, population scale, and urbanization vary substantially across regions and over time. These findings complement and refine the conclusions of firm-level studies such as Song et al. [

11], which do not explicitly account for spatial heterogeneity.