1. Introduction

Active and light mobility have become central to urban and extra-urban planning over the past two decades, aligning with the United Nations (UN)’ Agenda 2030 ref. [

1] and addressing challenges such as climate change, air pollution and public health, emphasizing the need for a user-centred approach in mobility planning. In this review, the term “active and light mobility” is used as an umbrella concept that includes bicycles, e-bikes and electric scooters as environmentally friendly modes of transportation used for short trips. This terminology ensures conceptual coherence and avoids fragmentation between existing definitions in the literature. The UN, as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals, emphasized that “cities must evolve to become more resilient, inclusive and sustainable”, making active and light mobility a key element for achieving these goals.

In this context, the “15-Minute City” concept, introduced by ref. [

2], represents a model in which essential services are reachable within 15 min by walk or by bicycle, discouraging the use of cars and supporting human-scale, inclusive and sustainable cities. This model enhances urban life by promoting local communities, strengthening place identity and improving access to daily services, prioritizing people’s needs and well-being.

Past research has focused primarily on infrastructure design, with limited or incomplete consideration of users’ preferences, behaviours and needs. This gap limits the effectiveness of mobility solutions, often leaving infrastructure underutilized. Recent studies highlight the importance of integrating user experience into mobility planning to better understand how to improve accessibility, comfort and adoption.

However, the literature remains fragmented across vehicle categories (traditional bicycles, e-bikes and e-scooters), user demographics, territorial contexts and methodologies. Some studies use discrete choice models for perceived safety/efficiency, and others apply qualitative approaches (interviews/focus groups) for subjective motivations refs. [

3,

4,

5].

Only a few works combine both quantitative and qualitative approaches, offering a fuller understanding refs. [

5,

6], particularly in contexts where important factors might otherwise be overlooked. For instance, ref. [

7] proposes a conceptual framework that articulates the cycling experience through social, sensorial and spatial dimensions, suggesting novel mixed methodologies—textual, visual and evaluative—for studying urban cycling, while [

8] highlights how the Italian National Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs) often emphasize infrastructure over more integrated, user-centric strategies. As observed by [

9] in Trieste (Italy), many users have turned to cycling as a substitute for public transport or walking, rather than as an alternative to the private car. In this context, the disconnect between infrastructure planning and user behaviour has become increasingly persistent.

In addition to infrastructure and accessibility, recent research highlights physiological and environmental comfort as key determinants of mobility adoption. These aspects influence users’ perceptions of the quality, well-being, safety and inclusiveness of the mobility environment, shaping their propensity to choose active and lightweight modes. Integrating comfort factors (e.g., vibration and noise) into mobility planning helps bridge the gap between infrastructure design and user-centred approaches, strengthening the link between active and light mobility, liveability and everyday usability.

Although research on active and light mobility has grown significantly over the past two decades, the scientific literature remains methodologically heterogeneous and fragmented. Studies differ in transportation modes, territorial contexts, user typologies and methods, and only a limited number offer integrated frameworks that combine behavioural, infrastructural and perceptual factors.

As a result, it remains difficult to compare findings across studies or to identify consistent patterns that planners and policymakers can operationalize. To address this gap, the present review aims to provide a structured and multidimensional synthesis of the available evidence.

This heterogeneity reduces the practical applicability of the results and limits the replicability of the tools, particularly when aiming to develop attractiveness indexes and user-oriented evaluation criteria. This study addresses this gap by providing a structured and comparative classification of the influencing factors, linking methodologies, user characteristics and infrastructure attributes within a single operational synthesis.

Based on these insights, this review is guided by three central research questions (RQs):

Which behavioural, perceptual and infrastructural factors most influence users’ choices regarding active and light mobility?

What methods are currently used to investigate these factors across different contexts?

How can these heterogeneous findings be translated into an operational framework supporting planning, evaluation and attractiveness assessment?

To operationalize these broad questions, we further divide them into five specific research questions (RQs), as detailed in Materials and Methods. This approach ensures both conceptual alignment with our overall objectives and methodological rigor for evidence extraction and synthesis. The goal is to provide planners, engineers and policymakers with a clear, practical tool to guide the design and evaluation of cycling infrastructure and services in the development of user-informed attractiveness indexes and decision-making tools. Moreover, the study contributes to a broader national research initiative focused on developing personalized, user-centric mobility solutions, preparing the ground for future empirical research to promote safe, attractive and inclusive active and light mobility systems. Thus, the study presents an operational framework informed by a selection of representative studies, focusing on practical application.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the methodology used to identify and analyse influential factors.

Section 3 presents a detailed review of the existing literature on key factors influencing users’ behaviour and preferences in active and light mobility planning.

Section 4 discusses the findings, and

Section 5 explores the limits and discusses future studies, while

Section 6 concludes with practical implications and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Plan and Objectives

This study adopts a critical and thematic literature review methodology to identify and synthesize key factors influencing user behaviour in active and light mobility contexts, following a screening protocol to ensure transparency and replicability. The aim is to support the development of attractiveness indexes and decision-making tools for user-centred planning, evaluation and prioritization of mobility infrastructure.

The review focuses on behavioural, perceptual, infrastructural and methodological dimensions and explores theoretical and methodological approaches with particular emphasis on active and light mobility. This approach allows the extraction of comparable evidence across heterogeneous studies, providing the basis for the synthesis tables and operational framework developed in later sections.

2.2. Research Questions

The five operational research questions (

Table 1) correspond to the three main research questions introduced previously.

The five research questions clarify the objectives of the review:

- -

RQ1–RQ3 identify the scope and the behavioural and infrastructural factors (supporting Introduction RQ1);

- -

RQ4 clarifies the methodological guidelines relevant to future data collection (supporting Introduction RQ2);

- -

RQ5 assesses the transferability of the findings to the development of user attractiveness indexes and planning tools (supporting Introduction RQ3).

Together, they ensure full alignment between the objectives and the analytical framework of the review. These RQs also guide the extraction, categorization and comparison of factors, which ultimately feed into the synthesis frameworks presented in

Section 4.

2.3. Research Strategy and Databases

A total of 117 records were identified through keyword searches in academic databases (Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar) for studies published between 2003 and 2023. After removing 12 ineligible documents (the grey literature, non-peer-reviewed sources and incomplete or inaccessible full texts), a final set of 105 studies, published between 2003 and 2023 in international academic journals on active and light mobility in urban and extra-urban contexts, was selected for thematic analysis and screening. Studies focused on the design of cycling infrastructures, the psychology of transport and the analysis of factors that influence users’ mobility choices were included.

Relevant contributions were identified using predefined keywords. The review was conducted using multiple combinations of keywords related to the concept of active and light mobility. Initial search terms were iteratively refined to focus on contributions explicitly linking user choices with environmental, infrastructural or perceptual attributes, and they included the following: “active mobility”, “light mobility”, “bike”, “bicycle”, “cyclist”, “e-bike” and “e-scooter” combined with user-related keywords such as “user”, “behaviour”, “preference”, “factor” and “indicator.” Various Boolean combinations were tested and iteratively refined to optimize the retrieval of relevant studies across the databases.

The search strategy progressively shifted to more targeted queries, focusing on studies that explicitly linked user choices to environmental, infrastructural or perceptual attributes. Keywords have therefore been refined to avoid retrieving studies only marginally related to the aims of this review, reducing them to “active mobility”, “light mobility”, “user behaviour” and “factor.”

2.4. Quality Assessment

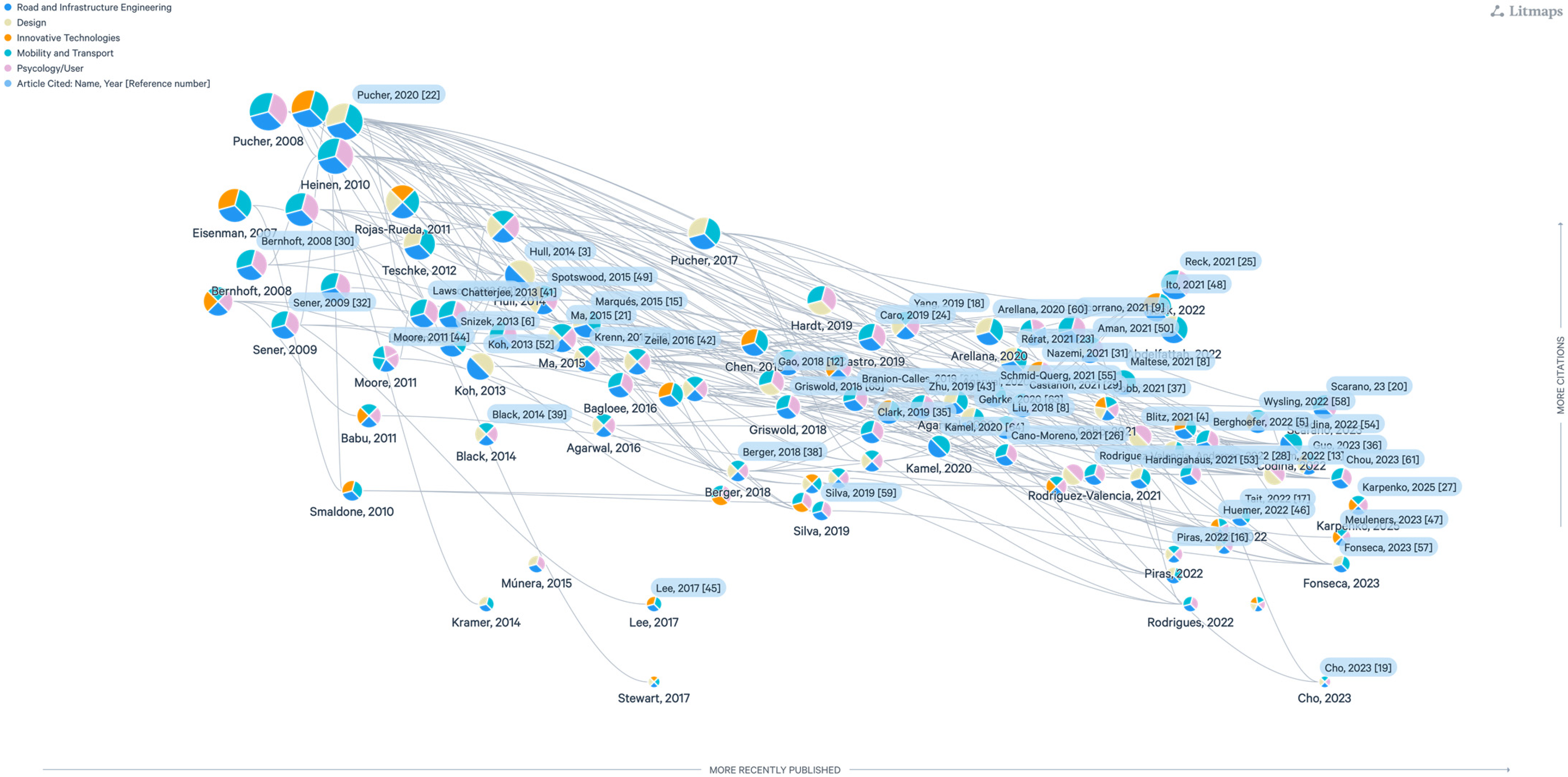

Figure 1 shows a mapping of the main papers analysed, identified by author and year of publication: the pie chart illustrates each paper’s relevance across the five key thematic areas identified for this study (innovative technologies, mobility and transport, road infrastructure engineering, psychology/sociology and design). The number of citations for each paper is represented by the size of the circle, so it increases with the ordinate axis, while the abscissa axis indicates the temporal dimension of publication, while the grey links represent citations among authors, illustrating thematic connections across studies.

The following map in

Figure 1, created using ref. [

10], reports the 107 scientific articles analysed, assembled through web scraping and listed in the bibliography section, while the articles cited are reported in the references.

Each of the articles underwent a two-level evaluation framework (

Table 2):

- -

Academic rigor, clarity and relevance (Q1–Q5);

- -

Methodological robustness and behavioural relevance (Q6–Q10): sample size, replicability, behavioural focus and thematic alignment.

Screening questions Q1–Q10 do not assess the scientific merit of the studies, but only the presence of essential elements necessary to extract comparable information for this review.

The screening aimed to ensure extractability and comparability of factors, rather than to rank scientific merit. All questions were equally weighted and only articles meeting at least 7 of 10 questions of

Table 2 were included. This ensured a balance between methodological rigor and thematic breadth, avoiding the exclusion of innovative or mixed-methods studies that offer valuable behavioural insights.

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 3 summarizes the criteria of the screening process, covering publication quality, thematic focus, methodology and data availability. These criteria were defined to ensure that selected studies provided actionable factors, measurable indicators or explicit behavioural insights relevant to planning tools and attractiveness evaluation.

2.6. Final Selection and Classification

This methodology allows the summary of the main factors that influence the user’s choice and to identify the most relevant criteria for the evaluation of the attractiveness of cycle paths, with particular attention to aspects related to active and light mobility.

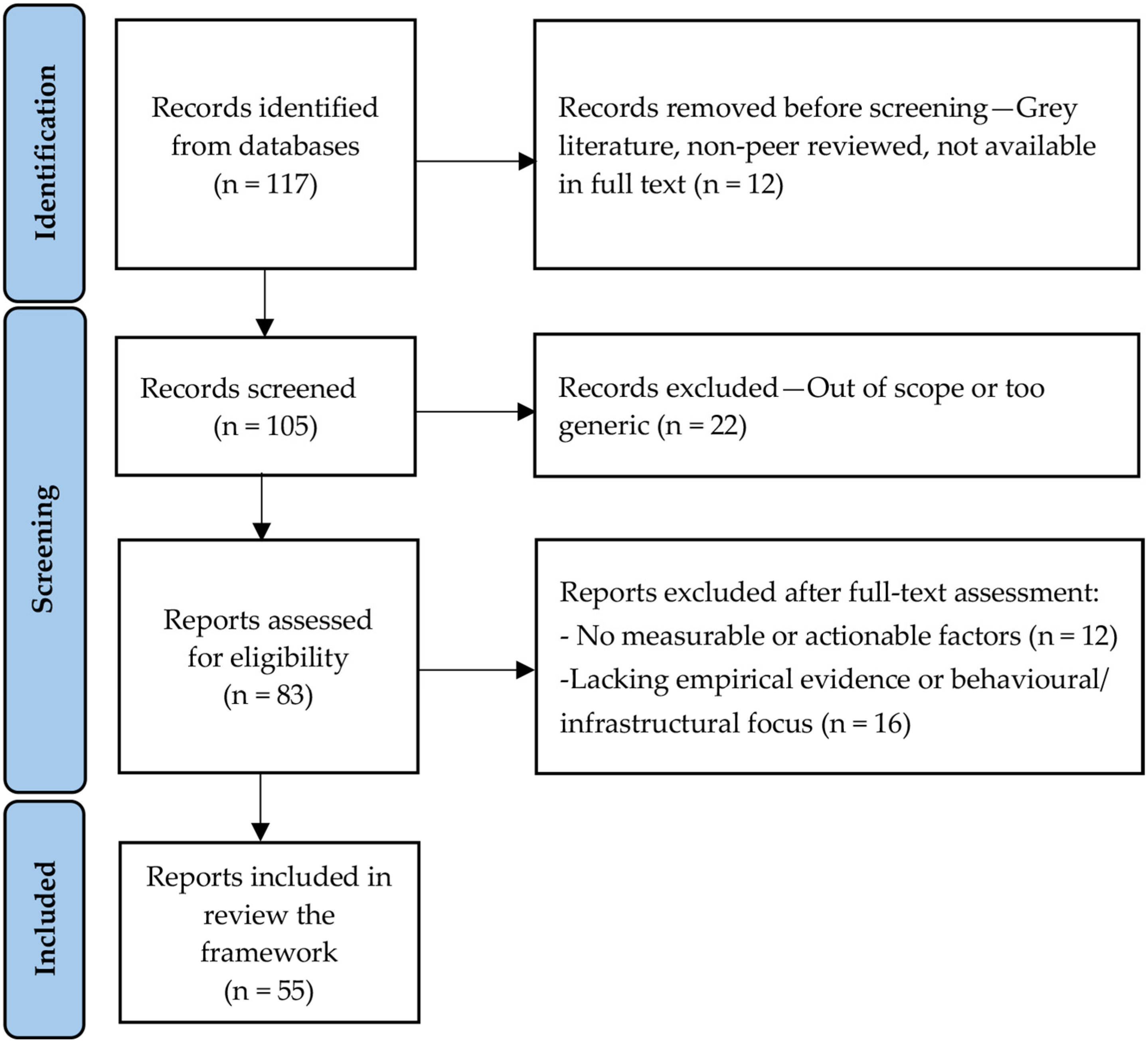

Figure 2 provides a simplified PRISMA flow diagram ref. [

11] summarizing the screening and selection process. This screening was conducted following the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in

Section 2.5 and the quality assessment framework described in

Section 2.4.

Studies that passed this preliminary stage underwent a full-text assessment guided by a specific definition of relevance: presence of behavioural or perceptual factors, identifiable infrastructure attributes, structured and replicable methodologies and measurable indicators applicable to planning or evaluation. Full-text studies were therefore excluded if they did not provide identifiable or actionable factors or indicators, were purely descriptive or lacked empirical evidence or a coherent analytical framework.

Of the 105 studies initially identified, 83 were reviewed in full and 55 were ultimately included, having met at least 7 of the 10 quality criteria and aligned with the defined relevance requirements.

3. Findings and Thematic Synthesis from the Literature Review

3.1. Identification of Analytical Macro-Categories

The selected studies were then classified across five analytical dimensions:

Macro-attributes or factors (environment, infrastructure, comfort, safety, etc.)

Means of transport involved (bike, e-bike and e-scooter)

Users’ typology (gender, age and expertise)

Typology of experiment and analysis method (with simulator or in situ, interviews, registration of psychophysical and dynamic data, GPS data analysis, etc.)

Investigated characteristics and attributes of network affecting users’ choice (paving, degree of separation from motorized traffic, etc.).

In the following, significant findings and case studies related to the above classification elements are synthetized. This allows a clearer and more intuitive understanding of the associations between factors, transport modes, user types, experimental approaches and network attributes. Results are summarized in two tables of

Section 4, reporting case studies (and authors), objectives, analysis methodology and application level.

3.2. Thematic Analysis of the Literature

This sub-section synthetizes the main findings from specific studies analysed and classified according to five macro-criteria of classification that we identified during the definition of the literature review methodology and through which it is possible to understand the complexity of the topic. Thus, some particularly representative studies are mentioned and briefly described.

3.2.1. Macro-Attributes or Factors Considered (Surrounding Environment, Infrastructure, Comfort, Safety, etc.)

By examining infrastructure-related factors, through a literature review, ref. [

3] deduce that the key factor influencing bicycle use is the cyclist’s perception of safety within their neighbourhood. In this study, the authors focused on the cities of Edinburgh, Cambridge, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht considering the parameters of coherence, directness, attractiveness, safety and comfort of the network through expert and non-expert cyclists.

A similar conclusion is also highlighted by ref. [

4] who show that the perceived safety and suitability of cycle paths is linked to individual perceptions of the local environment in terms of cycling infrastructure and quality of public space, as well as unbuilt environment and traffic conditions.

Building upon these insights, more recent research has further refined the concept of comfort and perceived safety.

For example, ref. [

12] developed the Dynamic Cycling Comfort (DCC) system, which uses accelerometers on shared bicycles to collect real-time data on vibrations perceived by cyclists.

Their findings show that vibration levels significantly affect the comfort of cycling and may represent a major deterrent to frequent bicycle use. Comfort was found to be influenced by environmental factors such as urban scenery, road geometry and traffic.

Furthermore, ref. [

13] examined physiological methods to assess stress and comfort during cycling, including heart rate and skin conductance. The results suggest that these physiological indicators can differ significantly from self-reported perceptions, highlighting to the need for a combined qualitative and quantitative approach in assessing cyclist experience.

While the above studies emphasize subjective dimensions, other works have focused on more objective criteria for bicycle suitability, particularly in urban contexts. The interaction between subjective perception and objective design is further explored by ref. [

14], who propose a conceptual model for evaluating the quality of service (QoS) of cycling infrastructure. Their model integrates both structural characteristics and perceived user experience, demonstrating that subjective factors, such as perceived safety and ease of use, often have greater explanatory power than purely geometric or operational variables. Similarly, ref. [

5], using the Repertory Grid technique, distinguishes between physical and mental comfort, emphasizing relational aspects and interaction with other road users as central to cyclists’ evaluations of infrastructure. The investigations showed that cycling without stress, safely and without stopping is very important for cyclists, thus with less intense traffic, low speed and segregated paths.

Evidence from applied contexts also reinforces the importance of both design and equity. For example, ref. [

15] demonstrated that the development of a fully segregated and well-designed cycling network—and so connected, continuous, bi-directional—in Seville led to a significant increase in utilitarian cycling, even in a city with no strong prior cycling culture, while ref. [

16] found that urban transformation and street requalification in Cagliari can increase bicycle usage among residents, emphasizing the importance of combining infrastructure with cycling services, policies and urban regeneration to improve safety and liveability.

Finally, concerns about equity in cycling infrastructure are raised by ref. [

17], who analysed the case of London. Their study reveals that peripheral neighbourhoods tend to have fewer and lower-quality cycling infrastructure (with less cycle lanes, signals for cyclist, bike boxes, etc.) which in turn limits the adoption of active mobility in those areas. These findings are supported by further studies ref. [

18,

19,

20,

21], which confirm the influence of built environment characteristics—such as network connectivity, dedicated cycle paths, facilities and separation from pedestrian paths—on both cycling behaviour and perceived safety.

In a broader perspective, the international review made by ref. [

22] analysed cities with high rates of bicycle use and found a correlation between high-quality infrastructure combined with initiatives and cycling policies aimed at improving safety and comfort.

3.2.2. Means of Transport Involved (Bike, E-Bike and E-Scooter)

As mentioned above and will be further explained below, the literature is rich in references and studies regarding traditional bicycles, covering various aspects and contexts. However, research on e-bikes and electric scooters remains relatively limited, as they have only recently begun to be widely adopted. Consequently, it has become increasingly important to investigate the factors that influence the attractiveness of the routes on which they are used and compare them with those of traditional bicycles.

Among the studies examined, ref. [

23] stands out for its focus on user profiles and cycling habits in Switzerland. This aligns with the classification framework developed in our review. Through a large-scale survey, it explored various factors including user profiles, frequency of cycling (and other means of transport), riding skills, bicycle ownership, trip types and motivations (from and to residence), as well as the cyclability of spaces and the presence of obstacles along commuting routes. The study found that e-bikes enable a wider age group to adopt this mode of transport, helping to overcome some infrastructural barriers that may limit the use of traditional bicycles. Similarly, ref. [

24] highlighted that e-bikes should be promoted as a better option than conventional bicycles in case of longer journey. However, more accurate analyses will be needed to identify the factors that have the greatest impact, in order to guarantee safety paths even at higher speeds.

In another study, ref. [

25]’s GPS tracking and survey data were used to estimate a choice model, showing that distance travelled, weather conditions and trip length are key determinants in the selection of micromobility modes. Moreover, they found that both e-scooters and personal e-bikes emit less CO

2 than the transport modes they replace, unlike shared modes.

Physical comfort has also emerged as a central aspect in evaluating the attractiveness of electric micromobility. For instance, ref. [

12] found that “shared bikes equipped with solid tires generate more vibrations compared to those with inflatable tires”, affecting the perceived comfort and so, the vehicle attractiveness. This issue becomes even more critical for e-scooters. In a dedicated study ref. [

26], the effects of vibration at 25 km/h on user comfort and health were analysed for the first time. The findings indicate that, for a standard electric scooter on a surface with “good–very good” roughness, discomfort begins at a speed of 16 km/h, and at 23 km/h vibrations can reach levels potentially harmful to health. It also emphasizes the need to improve vehicle design to enhance comfort and safety.

Similarly ref. [

27] investigated vertical vibrations and frequency transmission on different urban pavements for e-scooter, confirming that surface irregularities can significantly impact perceived comfort and potentially affect health outcomes.

From a health perspective, ref. [

28] highlights that e-bike use can significantly improve both mental and physical well-being, particularly among inactive, overweight or obese individuals promoting health and happiness in populations that are typically less engaged in physical activity.

Meanwhile, ref. [

20] recognized e-bikes as an emerging topic in road safety research, stressing that higher speeds and the mixed nature of e-bike traffic introduce new challenges in terms of crash severity and infrastructure design standards. Therefore, analysing the attractiveness of different micromobility vehicles requires considering not only infrastructural and behavioural aspects but also mechanical and physiological dimensions such as vibrations, comfort, speed and health impact. This multifactorial approach is necessary to develop inclusive, safe and truly effective active mobility strategies that consider the diversity of micromobility users.

3.2.3. Users’ Typology (Gender, Age, Experts and Non-Experts)

Several studies have investigated how preferences, perceptions of infrastructural elements and predisposition to cycling change depending on user category and on certain physical and socioeconomic characteristics.

For instance, ref. [

29], through a structured literature review, identified 17 criteria, divided into four main areas (cycling infrastructure, safety, accessibility and surrounding environment) that can be analysed in different contexts in order to determine its cyclability.

As far as the user is concerned, the most recurrent considerations are mainly aimed at gender, age, profession and type of study, the propensity to use light vehicles and therefore the frequency with which they use them, classifying users as experts or non-experts.

Age, in particular, appears to play a central role in shaping perceptions of safety and infrastructure. In studying the risk perception and the behaviour of pedestrians and cyclists in cities, ref. [

30] used a questionnaire focused on the age of users, with the result that older people appreciate pedestrian crossings, traffic-lighted intersections, pavements and cycle paths much more than younger respondents, preferring safety over speed.

Similar trends were confirmed by ref. [

31], who used a 360-degree immersive virtual reality (VR) cycling simulator to assess the Perceived Level of Safety (PLOS) and Willingness to Bike (WTB). Their findings indicated that older participants reported higher safety concerns, consistent with previous studies refs. [

32,

33,

34,

35].

Ref. [

36], through an experimental setup combining a bicycle simulator with mobile sensing devices, analysed behavioural and physiological responses to different bike lane designs (shared, curb side and protected). While gender influenced safety perception, age and other variables did not significantly affect cycling performance or stress responses. Physiological approaches in relation to the type of user have also been employed by ref. [

37], who used galvanic skin response to monitor stress levels in cyclists, while ref. [

38] applied eye-tracking and electrodermal activity sensors to identify high-stress events during rides and test sensor-based data collection methods.

For what concern research on older adults, ref. [

39] emphasizes the importance of urban design elements in affecting perceptions of the built environment and in encouraging active travel among elderly populations. Similarly, ref. [

30] shows that older pedestrians and cyclists, due to differences in health and abilities, prioritize safety features such as pedestrian crossings and pavements more than younger people, highlighting the need for inclusive infrastructure.

Recent studies also explore electric micromobility users. Ref. [

40], examining e-bike usage in Lausanne, found that age, gender and frequency of use significantly influence comfort and satisfaction levels.

Additionally, ref. [

19] identified diverging priorities between Personal Mobility Device (PMD) users and non-users. While users emphasize infrastructure aspects, such as road surface continuity and obstacle management, non-users emphasize enforcement and safety education.

Finally, cycling behaviour can also evolve over time. Ref. [

41] have shown that life events such as changes in occupation, family structure or health status can have a significant impact on cycling frequency and attitudes. Thus, mobility planning needs to consider the dynamic nature of users’ behaviour across the lifespan.

These findings underline the necessity of user-centred planning approaches that address the heterogeneous needs and perceptions of diverse demographic groups, in order to promote equitable and effective cycling environments.

3.2.4. Typology of Experiment and Analysis Method (With Simulator or In Situ, Interviews, Registration of Psychophysical and Dynamic Data, Analysis of GPS Data, etc.)

Studies on cycling and micromobility employ a variety of research methods, from in situ experiments to virtual simulations, as well as mixed approaches that integrate quantitative and qualitative data, enabling a comprehensive assessment of the infrastructural and behavioural factors that influence user experience and mobility choices.

In situ experiments allow researchers to evaluate comfort and usability in real-life context, including factors such as road surface quality, infrastructure network and the surrounding environment. These studies often involve sensors and video recordings to monitor user behaviour and physiological responses ref. [

42].

Similarly, ref. [

43] developed a Cycling Comfort Index (CCI) using an Instrumented Probe Bicycle (IPB) in Singapore, equipped with sensors and automated video analysis, employing the XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) method to objectively and efficiently assess cycling comfort and better predict cyclists’ perceptions compared to traditional methods, thus confirming the potential of advanced technologies for objective evaluations of road conditions and infrastructure comfort.

However, real-world testing is not always feasible or ethical, especially when involving non-expert users in complex or potentially dangerous traffic scenarios. In such cases, simulation methods offer a controlled and replicable environment to explore user responses to various design configurations. As early as 2009/2010, laboratory investigations, as in refs. [

44,

45], into control situations were conducted to identify user movements, and over time these investigations were implemented with the development of simulators. These tools have laid the foundation for virtual-reality-based cycling simulators, providing insights for scenario testing.

As demonstrated by ref. [

46], simulation approaches are also cost-effective for early stage infrastructure assessment, allowing designers to eliminate less favourable solutions before implementation. Using a cycling simulator and an online survey, the study found that stronger visual separation between parked cars and traffic, along with bicycle pictograms, increased cyclists’ lateral distance from parked cars and improved perceptions of safety and comfort.

As already seen, ref. [

31] also integrates VR and survey to analyse how different cycling environments influence the perception of safety and the willingness to cycle.

However, since user behaviour in simulations may differ from real life, the results are most valid for relative comparisons between conditions, highlighting the need to complement simulations with real-world feedback to enhance ecological validity.

For example, ref. [

47] used a simulator to show that widening bike lanes on curves significantly reduces lane excursions and improves perceived safety, while sharrows provide minimal protection, highlighting the benefits of wider bike lanes in enhancing cyclist safety on curved roads.

Refs. [

13,

36,

37], highlight the use of sensors to monitor cyclist stress and attention, though physiological data only loosely correlate with self-reported comfort. These findings suggest combining simulations, sensor data and user feedback can better inform a safer, more comfortable cycling design.

In addition to simulation-based and real-world assessments, interviews and GPS data are frequently used either independently or as part of a mixed-method approach. Ref. [

7], explored user experiences on cycle highways, emphasising the role of perceived quality and co-design principles in infrastructure evaluation.

A complementary approach uses artificial intelligence for visual audits. Ref. [

48] applied computer vision to Google Street View images to develop a comprehensive, scalable bikeability index, showing that this method outperforms traditional techniques while suggesting a combined use of both approaches for best results.

Interviews and GPS data can also be applied in two distinct ways: either by integrating them with findings from simulation-based or in situ experiments or as standalone tools for specific investigations. For example, study ref. [

5], previously discussed, used qualitative interviews to explore user perceptions and emotional responses. This highlights the continued relevance of qualitative research, which can offer significant added value when combined with other methods.

Ref. [

26] used semi-structured interviews to better understand the motivations faced by e-bike users in particular related to vibrations and comfort, while ref. [

41] investigated behavioural changes in the UK through detailed life history interviews.

Methods of this type are versatile and have also been used in socioeconomic preference analyses. A couple of examples are reported here, although not included in the final outcome of the studies. Ref. [

49] reinterpreted quantitative and qualitative data through the lens of Social Practice Theory, revealing sociocultural factors that shape transportation habits.

Ref. [

50] applied Latent Dirichlet Allocation and machine learning to over 12,000 app store reviews of major e-scooter providers, highlighting key themes such as pricing, safety, usability and customer support, while also revealing gender differences in user satisfaction.

Finally, ref. [

51] showed how geolocated transactional data can be analysed to evaluate the impact of micromobility infrastructure on local commerce, providing an innovative framework for assessing the broader socioeconomic implications of light and active mobility systems.

3.2.5. Investigated Characteristics and Attributes of Network Affecting Users’ Choice (Paving, Separation Degree from Motorized Traffic, etc.)

This final section of the review focuses on case studies in which user route choices were recorded and mapped, with the aim of identifying frequent associations between those choices and specific infrastructural characteristics. The goal was to determine which network attributes most strongly influence users’ preferences and behaviours.

A first example is provided by ref. [

52], who used surveys and audits to identify key infrastructural factors influencing route choice for walking and cycling, finding that comfort, safety and environmental quality strongly affect preferences, with rain shelter important for walkers and security for cyclists.

In a multifactorial analysis, ref. [

53] weighted the most influential factors affecting cycling infrastructure, drawing from a literature review, expert surveys and geodata analysis. The key elements identified included network connectivity, the presence of neighbourhood streets, greenways and repair or rental facilities. Similar findings emerged from the Copenhagen/Frederiksberg case study ref. [

6], where although cyclists frequently used main roads, their perceptions were negatively impacted by infrastructural features such as bus stops, intersections (both signalized and unsignalized) and high traffic volumes.

Ref. [

54] developed a bikeability index for Barcelona using GIS data and cycling surveys, incorporating factors like dedicated infrastructure, slopes, safety, connectivity and traffic. They validated the index against actual travel behaviour, finding that residents in areas with better bikeability features cycle more often, providing a useful tool for urban planning in dense Mediterranean cities.

In Munich, ref. [

55] developed a bikeability index using a GIS methodology with infrastructure data and field surveys, focusing on cycling infrastructure, speed limits, bicycle parking and intersection quality.

Then, in Graz ref. [

56], researchers evaluated 278 cycling routes, examining environmental attributes such as green areas, cycle paths and topographical features, reaffirming the usefulness of GIS tools for accessibility mapping and active mobility planning.

Also, in Portugal, ref. [

57] applied a GIS-based approach in Ponte de Lima to design a cycling network from scratch, identifying topography, population density and age distribution as critical barriers. Their findings also underscored the positive influence of a compact urban form, road integration and supporting measures such as traffic calming and bike-sharing systems.

Building on open-source tools, ref. [

58] developed a reproducible and scalable method for assessing bikeability in Paris by combining OpenStreetMap (OSM) and planning data.

In emerging cycling contexts, ref. [

59,

60] assessed their own tools to support strategic cycling infrastructure planning. Ref. [

59] mapped cycling potential in Porto using demographic and urban data, while ref. [

60] developed a cycling index for Barranquilla, Colombia, integrating user perceptions, socioeconomic factors and travel purposes. Both studies highlight the importance of safety and direct routes for commuters, as well as aesthetics and comfort for recreational cyclists, underscoring the need for context-specific planning.

On a larger scale, ref. [

61] analysed crowdsourced GPS data in Copenhagen, demonstrating that well-connected areas with dedicated infrastructure and cycling expressways reduce cyclist detours and improve accessibility.

Ref. [

62] simulated a segregated bicycle superhighway in Patna, India, demonstrating potential modal shifts toward cycling and emission reductions, though sharing routes with motorbikes reduces these benefits.

Regarding modelling and strategic planning, ref. [

63] highlight that many U.S. cities invest in safe and low-stress facilities to increased cycling and societal benefits. To maximize network connectivity, even with limited budgets, they developed the Cyclist Routing Algorithm for Network Connectivity (CRANC), a simulation tool balancing travel time and traffic stress to model diverse cyclist preferences.

Complementing this, ref. [

64] introduced a Bike Composite Index (BCI) integrating two dimensions: attractiveness (network density, land use mix and slope) and safety (crash risk and infrastructure features). Their findings emphasize that attractiveness and safety are weakly correlated but both critical for effective bike-friendly planning.

From a behavioural perspective, ref. [

65] developed a user-centred Level of Service (LOS) measure for cyclists, using surveys, video stimuli and latent class choice modelling to capture diverse cyclist preferences and needs. This approach allows for more personalized assessments by segmenting cyclist types based on empirically observed behaviours.

Together, these studies demonstrate the multifaceted nature of cycling infrastructure planning, highlighting the need to integrate behavioural insights, empirical data and context-specific factors to create networks that effectively serve diverse cyclist populations.

3.3. Finding Operational Synthesis and Relations to RQs

3.3.1. Cross-Sectional Synthesis

The classification presented in this section allowed the identification of recurring patterns, highlighting key factors influencing user behaviour, transport modes and methodological approaches. It is noteworthy that the five categories defined in the review are not entirely orthogonal. This is intentional: cycling and micromobility are multidimensional, and infrastructure, user profiles, comfort and methods often overlap. Consequently, different outcomes emerge depending on the context, users, transportation modes, methods and infrastructure.

The adopted framework offers a pragmatic and scalable way to organize fragmented data while preserving its complexity. The results confirm that infrastructure significantly influences perceived safety and comfort, while contextual factors such as traffic density and green spaces influence route choice.

Methodological heterogeneity remains a major challenge, as studies range from self-reported surveys to in situ tests, data tracking, VR simulations and psychophysiological measurements.

Also, significant variability across transport modes (bike, e-bike and e-scooter) and user typologies complicates direct comparison. This diversity enriches the evidence base but reduces replicability and limits cross-study synthesis.

However, the lack of consistency in data collection and reference scales complicates data consolidation. The classification of user types highlights the need for user-centred planning, especially for new or potential cyclists.

These insights were systematized in

Table 4 and

Table 5, which serve as the foundation for the development of an operational framework aimed at supporting planning decisions and behavioural analysis. In particular, the combination of user typologies, transport modes and infrastructure features, linked with the most suitable analysis methods, allows for the direct application of these findings in urban design, simulation modelling or infrastructure evaluation processes.

3.3.2. Contribution to Research Sub-Questions (RQ1–RQ5)

Thus, the five specific research sub-questions (RQ1–RQ5) should be interpreted as a lens to address the broader objectives of identifying influential factors, mapping the methods used to investigate them and supporting the comparison of planning approaches:

- -

RQ1 (which modes of light and active mobility have been most studied?) is addressed in

Section 3.2.2 and highlights a strong predominance of studies focusing on conventional bicycles, while e-bikes and electric scooters remain underrepresented. Although recent contributions increasingly address electric micromobility, the evidence base remains fragmented.

- -

RQ2 (what user characteristics are analysed?) is addressed in

Section 3.2.3, which shows that age, gender, experience level and frequency of use are the most commonly investigated user attributes, while perceptions of safety, comfort and infrastructure quality vary across user groups, particularly between younger and older users and between expert and non-expert cyclists.

- -

RQ3 (what common influencing factors are reported across modes?) is addressed in

Section 3.2.1 and

Section 3.2.5. Across all modes, perceived safety, comfort, infrastructure continuity, separation from motorized traffic and surface quality emerge as recurring determinants of route choice and attractiveness.

- -

RQ4 (what research methods and experimental setups are used?) is addressed in

Section 3.2.4 and reveals methodological heterogeneity, including surveys, qualitative interviews, in situ experiments, GPS tracking, physiological sensing and VR simulations. This diversity reflects the complexity of studying, comparing and replicating active mobility systems across studies.

- -

RQ5 (are there validated, transferable factors suitable across contexts?) is addressed in

Section 3.2.1 and

Section 3.2.5. While factors such as safety, comfort, connectivity and infrastructure quality are consistently identified, their relative importance varies across contexts, transport modes and user groups. This aspect is further discussed in

Section 5.

4. Results

From the carried-out review of the literature, it was possible to identify a large number of studies at a worldwide level, although some aspects remain underexplored. While generally high in quality, the studies analysed lack consistency in terms of the evaluation criteria and parameters selected, as well as the types of users considered and the analysis methodologies employed.

This demonstrates a growing interest in the topic, but it also highlights the lack of a shared analytical framework, making cross-comparison and generalization of findings more difficult.

The focus of the studies is different depending on the various situations analysed, the scenarios evaluated, the designated study area, the criteria considerations, the adopted methodology and the types.

Studies were selected based on their relevance, methodological rigor and representativeness of key thematic areas. While this selection is not exhaustive, it highlights the most influential contributions for each macro-criterion, providing a focused synthesis suitable for guiding practice and further research.

A key contribution of this study lies in the organization and classification of the existing literature, which led to the development of two summary tables aimed at guiding future research and practice.

The tables were developed by mapping each study onto the five macro-criteria and extracting factors, methods and results, ensuring representativeness of the main emerging patterns in the literature while maintaining clarity and usability for planners and researchers.

In

Table 4, the macro-criteria used to classify the analysed papers are given. For each of them, the criterion itself is better described, as well as the different approaches and methodologies found in relation to the criterion, the related objectives and the factors/data that best specify the various occurrences.

The literature analysis reveals key infrastructural factors influencing active and light mobility users’ choices, including vehicle type and route selection. These parameters are crucial for case studies, as they help determine route attractiveness and provide valuable insights for policymakers to implement targeted infrastructure interventions.

After analysing the most important and influential factors extracted, another table (

Table 5) was created. The first column identifies the factors whether related to infrastructure, external factors (e.g., traffic), geographic factors (e.g., slopes), convenience factors (e.g., proximity to facilities) and others.

For each macro-criterion, the review extracted the key factors most associated with influencing active and light mobility choices, describing their typical measurement units, suggested analysis methods (e.g., GIS, surveys and simulations) and the appropriate scale of application (e.g., segment, route and neighbourhood).

The references listed are illustrative examples selected for their relevance to each factor or macro-criterion; they do not constitute a comprehensive bibliography of all the literature in the field. This approach allows the framework to remain clear and operationally useful, focusing on studies that most strongly inform planning and analysis decisions.

Also, in both tables, the last column provides the references to the main studies associated, for those interested in deeper exploration.

Table 4.

Schematic view of the literature results associated with the macro-criteria of classification.

Table 4.

Schematic view of the literature results associated with the macro-criteria of classification.

| Macro-Criteria of Classification | Description | Method of

Analysis | Objectives | Factors/Data | References |

|---|

Macro—

attributes or

factors

considered | Analyse the

external factors that influence

users’ choice, e.g.,

environment,

infrastructure,

comfort and safety. | Quantitative (in situ

investigations and tests),

qualitative

(survey) | Examine the

influence of

external factors on user choices. | - -

Environment (greenery, pedestrian areas, noise…); - -

Infrastructures (pavement, signage…); - -

Comfort (dedicated space); - -

Safety (lighting, separation from traffic…)

| [3,4,5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] |

Means of transport

involved | Classify the users based on the means of transport used. | In situ tests,

interviews,

tracking data analysis | Study the

preferences

between

different means of transport and the aspects that

influence their choice. | - -

Bikes (traditional, racing, cargo, MTB…) - -

E-bike - -

E-scooter - -

Other (skateboard, light electric vehicles…)

| [23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Users’ typology | Analyse how

users’

demographic and

behavioural traits

influence their choices. | Survey,

interviews | Analyse the

differences in user behaviour based on their

typology. | - -

Gender - -

Age - -

Experts/Non experts - -

Motivations

| [19,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] |

Typology of

experiment and analysis method | Differentiate the methodological

approaches used to study user choice. | Simulations,

in situ tests,

psychophysical data

recording | Evaluate

physical and psychological

responses in

relation to

different

scenarios. | - -

Simulations (driving simulators and VR) - -

In situ test - -

Survey and interviews - -

Psychophysical data (stress, fatigue…) - -

Tracking data

| [5,7,8,13,26,31,36,37,41,42,43,46,47,48] |

By the

investigated

characteristics and attributes of network affecting users’ choice | Examines how

the features of

infrastructure

influence user choice. | GIS

analysis, in situ testing | Examine how the

infrastructure structure affects the choice. | - -

Paving (asphalt, pavé…) - -

Separation from traffic (segregated lanes) - -

Path width, accessibility

| [6,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] |

Table 5.

Factors associated to the level of application and to the most suitable methods of analysis.

Table 5.

Factors associated to the level of application and to the most suitable methods of analysis.

| Factor | Description/Unit

of Measure | Method of

Analysis | Level of

Application | References |

|---|

Geometry and

connectivity of the street | Type of cycle infrastructure

(separated cycle path, boulevard cycle path…) and

length (meters) | Surveys,

Interviews, GIS Analysis, In situ Test, Simulations | Segment-based | [3,5,6,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,29,30,31,33,35,36,37,38,42,43,46,47,48,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,65] |

| Smoothness of surface | Material of cycle paths | [3,5,12,19,26,27,33,42,43,60,64,65] |

| Traffic | Traffic volume

(vehicles/days) and

motorized vehicle speed (km/h) | In situ test, GIS analysis,

Surface Analysis | Route-based | [5,14,18,19,22,29,30,38,43,48,52,54,55,59,60,62,65] |

| Topography | Ascents/descents and

presence of slope and/or stairs | GPS Analysis, In situ Test, Traffic Analysis, | [18,43,52,54,56,57,59,63,64] |

| Intersection | Signalized intersection with or

without dedicated cycling traffic lights, distance

between contiguous | Simulations, In situ Test, GPS

Analysis,

Simulations, Traffic Analysis | Intersection-based | [3,6,14,18,29,30,33,38,42,47,48,54,55,60] |

| Proximity to community facilities | Type of facilities and

distance from cycle path

(meters or time) | GIS Analysis,

Surveys | Neighbourhood-based | [51,52,57,63] |

| Landscape | Presence of green/aquatic areas | Interviews, GIS Analysis | [3,4,6,12,28,29,43,48,53,54,56,59,61,62,64] |

Cycling

facilities | Type and density | Surveys, In situ Test,

GIS Analysis | [4,6,14,22,29,31,32,37,53,54,58,62,63,64] |

| Bike parking spaces | Presence and distance from bike paths (meters or time) | GIS Analysis,

Interviews | [3,5,6,15,19,22,29,54,55,57] |

It is important to emphasize that the tables presented are not intended to provide an exhaustive review of all the available literature but rather represent a strategic selection of studies deemed particularly significant and methodologically relevant with respect to the identified macro-criteria. Study selection criteria include representativeness of the factors considered, methodological quality and relevance for the construction of an operational framework.

This selection allows for the synthesis and comparison of fragmented findings in a manner useful for the design of active mobility infrastructures and strategies, minimizing the risk of data bias and ensuring practical applicability. The resulting framework should be understood as an operational and adaptable tool, not as an inference generalizable to all contexts or an alternative to a systematic review.

This integrated framework synthesizes the literature and aims to do the following:

Guide planners and engineers in selecting the relevant factors and metrics for their specific context;

Suggest the most suitable methodologies for data collection and analysis according to the factor and study scale;

Help decision-makers define interventions while also considering user typologies and modes of transport.

Thus, this framework simplifies planning and evaluating cycling infrastructure, reducing the need for stakeholders to consult the extensive and diverse literature. It provides a clear map that connect factors, methods and user profiles, facilitating the assessment and improvement of active and light mobility systems for all stakeholders.

It is important to note that this synthesis provides a conceptual and operational bridge between literature findings and practical applications. By focusing on representative studies and key factors, the framework facilitates a clear understanding of complex relationships while avoiding overwhelming detail from the full body of literature.

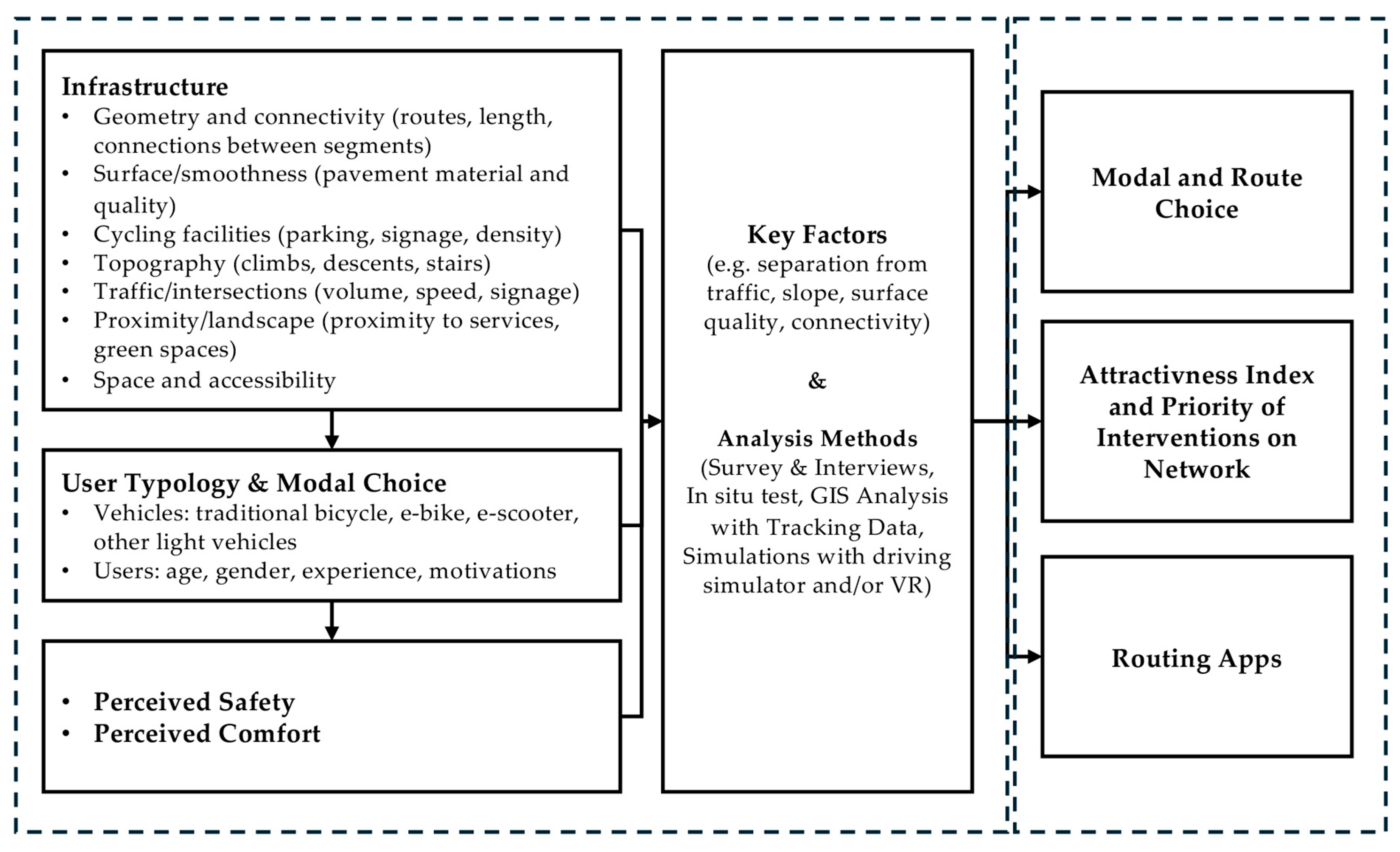

Furthermore, the results presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5 can be conceptually summarized in a simple framework (

Figure 3) that illustrates how infrastructure characteristics and user types influence perceived comfort and safety, which in turn shape user behaviour and ultimately contribute to modal choice.

The framework also distinguishes the practical applications of these findings, including attractiveness indexes (bikeability and/or cyclability indexes), network interventions planning and routing apps, clearly separating factor analysis from their operational implementation. This diagram highlights the multilevel interactions and provides a visual guide for planners and researchers.

5. Discussion and Limitations

This review aimed to consolidate a diverse body of the literature on active and light mobility into a coherent and integrated framework. By considering infrastructure characteristics, contextual conditions and user types, the study addresses the multidimensional nature of mobility systems. Designing exclusively for experienced cyclists, for example, is insufficient, as perceived comfort and safety vary significantly among users with different levels of experience, age and vehicle type.

The synthesis confirms that infrastructure quality consistently influences users’ perceptions of safety and comfort, while contextual factors, such as traffic density, environmental characteristics and road surface conditions, play a significant role in route choice.

These findings reinforce the need for inclusive, user-centred planning approaches that consider the behavioural and perceptual differences between cyclists, e-bike users and e-scooter users.

The recurring patterns identified in the literature inform the operational framework proposed in this study. The framework is visually summarized in

Figure 3 and operationally represented in

Table 4 and

Table 5, offering a clear linkage between literature evidence and practical application. This structure also lays the groundwork for developing replicable attractiveness indexes, decision support tools and GIS-based analyses.

5.1. Literature Limitations

Despite the growing body of research, gaps and limitations have been identified:

- -

Methodological heterogeneity: Studies range from surveys and interviews to in situ tests, GPS tracking, VR simulations and psychophysiological assessments. While this variety enriches, it also hinders direct comparisons, synthesis and the development of transferable indexes. Mixed approaches appear more effective for linking subjective perceptions with objective infrastructure attributes.

- -

Lack of standardization: Differences in user types, evaluation criteria and data collection scales make direct synthesis difficult.

- -

Imbalance between transportation modes: Conventional bicycles dominate the literature, while studies on e-bikes and electric scooters remain scarce.

- -

Contextual specificity: Most studies focus on specific urban environments, limiting the transferability of findings across regions or mobility systems.

Furthermore, aspects such as prolonged exposure to vibration, surface quality and associated stress or health risks, particularly relevant for e-bike and e-scooter users, are underexplored. Social, psychological and health-related dimensions also require further investigation to fully understand the long-term appeal of active mobility modes.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

While the review provides a comprehensive summary, several limitations must be acknowledged:

- -

The study was limited to full-text publications in English, potentially excluding relevant studies or the grey literature.

- -

Terminological inconsistencies across studies complicated classification and synthesis. Heterogeneous definitions, data collection protocols and evaluation metrics limited comparability and synthesis across studies.

- -

Limited focus on emerging modes: e-bikes and e-scooters are underrepresented, limiting our ability to generalize the findings to all light mobility modes.

- -

Context-specific factors: Many studies are region-specific, making the transferability of the findings to other urban contexts uncertain.

- -

Incomplete coverage of psychosocial factors: Health, stress and social influences are often understudied, yet they influence perceived comfort, safety and modal choice.

- -

Empirical validation of the proposed framework is still needed to confirm its applicability in real-world settings.

To address these issues, a future Italian case study is planned, incorporating mixed methods, including interviews, field surveys, GIS-based connectivity analyses and psychophysical measurements. This will allow for a robust assessment of the framework’s transferability, reliability and practical utility.

5.3. Future Research Directions

Next research will be guided by a concrete program:

Empirical validation of the framework with different user types (beginner vs. expert cyclists, e-bike and e-scooter users) to assess its robustness and transferability.

Behavioural and perceptual studies on comfort and safety perceptions, using mixed methods (interviews, field tests and simulators) to connect subjective experiences with objective infrastructure characteristics.

Spatial analysis and network connectivity assessed using GIS and tracking data.

Development of replicable attractiveness indexes and decision support tools, using GIS, tracking data and psychophysical measurements to guide urban planning interventions.

Context-specific case studies, including the planned Italian study, to determine which factors most significantly influence route choice, perceptions of safety and modal preference.

Future work should also consider emerging factors and technologies, such as accessibility, intermodal connectivity, intelligent transport systems (ITS) and accident risk, to further improve the applicability of the framework.

This research is part of a larger national research initiative, funded through a national program and contributes to its overall goals by laying the foundation for a personalized and user-centred mobility experience, while demonstrating the feasibility of a safe and sustainable mobility system based on light vehicles. As part of this initiative, the framework will be tested and refined through empirical studies to generate concrete insights for policymakers and urban planners.

6. Conclusions

This review explored the range of factors that influence the choice of active and light transport modes, identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and gaps in the existing literature. Although the literature is quite extensive, there is a lack of comprehensive studies, specifically for e-bikes and e-scooters, and a lack of standardization in methodologies, evaluation criteria, user typologies and data collection scales.

6.1. Addressing the Three Research Questions

This study directly contributes to addressing the three RQs defined in the Introduction:

The review identifies safety, comfort, connectivity, infrastructure quality and environmental context as the most influential factors. These determinants are consistent across different transport modes and user groups, although their importance varies depending on context, experience and vehicle type:

- 2.

What methods are currently used to investigate these factors across different contexts?

The literature shows substantial methodological heterogeneity, including surveys, interviews, in situ experiments, GPS tracking, virtual reality simulations and psychophysiological measurements. This study highlights the need for mixed-method approaches that combine subjective perceptions with objective measurements to produce reliable and transferable results:

- 3.

How can these heterogeneous findings be translated into an operational framework supporting planning, evaluation and attractiveness assessment?

The main contribution of this study is the development of an integrated framework that classifies and analyses factors influencing active and light mobility. This framework, synthesized into two summary tables and a conceptual diagram (

Figure 3) and offers a comprehensive tool for researchers, planners and policymakers. In particular, the following is provided:

- -

Table 4 introduces a set of macro-classification criteria based on user type, transport mode, analytical method and infrastructure characteristics, linking them to relevant literature studies, supporting replication and further research replication;

- -

Table 5 aligns key influencing factors with appropriate analysis and methodologies and literature references;

- -

Figure 3 conceptually summarizes these findings, illustrating how infrastructure characteristics and user types influence perceived comfort and safety, which in turn shape user behaviour and ultimately contribute to modal choice.

It also illustrates how these findings can be operationalized through practical tools such as attractiveness indexes, network interventions and routing apps. This highlights the multilevel interactions and provides a visual guide for decision-making processes.

It should be noted that, while

Table 4 and

Table 5 present results extracted directly from the review, the applications included in

Figure 3 are derived from the complementary literature and represent potential operational tools.

6.2. Bridging the Gap and Future Applications

By systematically synthesizing and classifying the literature, this study reduces fragmentation and facilitates comparability across contexts and user groups. The framework also does the following:

- -

Offers transferable criteria for assessing infrastructure and modal attractiveness.

- -

Supports user-centred planning, ensuring that projects meet the needs of diverse cycling and micromobility populations.

- -

Provides a basis for empirical validation and context-specific studies, including the planned Italian case study.

Future research should validate the framework and its resulting applications, ensuring that both the identified key factors and the proposed practical tools are effective and transferable across contexts, by the following:

- -

Testing the framework across different user types and urban contexts.

- -

Developing replicable attractiveness indexes for policy and planning interventions.

- -

Integrating emerging factors such as intermodal connectivity, intelligent transport systems (ITS) and accident risk into decision-making tools.

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that, despite the heterogeneity of existing studies, it is possible to construct a multidimensional and operational synthesis of the factors influencing active and light mobility. Also, the study provides a clear path for future research and the development of evidence-based, user-focused planning strategies.