1. Introduction

The seasonality of financial markets, especially the month-of-the-year effect, is one of the most persistent and controversial market anomalies, and its presence undermines the fundamental predictions of the efficient market hypothesis [

1]. Although extensive literature has documented the occurrence of the month-of-the-year effect in traditional capital markets [

2,

3,

4,

5], little is known about whether similar patterns occur in sustainable investment segments, especially in specialised indices based on the social pillar (S). This gap is significant because ESG indices may respond to different regulatory, informational and macroeconomic stimuli and thus exhibit seasonal patterns that differ from traditional benchmarks.

This gap is particularly evident in thematic indices such as the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders, which includes global companies with above-average performance on social factors while meeting stringent environmental and corporate governance criteria. The structure of the index allows for the analysis of market behavior characteristic of socially conscious investors, which, in light of the growing importance of the ‘S’ pillar in sustainable finance, is a particularly promising area of research.

The aim of this study is to identify and assess the strength and stability of the month-of-the-year effect in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index between 2011 and 2024. The focus is particularly on the four most documented monthly anomalies—the January, July, October and December Effects—whose occurrence in ESG indices has not yet been systematically studied. In response to this objective, the study verifies three hypotheses:

H1. Month-of-the-year effects in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index are statistically significant, and their occurrence is correlated with periods of increased macroeconomic uncertainty and increased regulatory and informational activity in the area of sustainable finance.

H2. The frequency of selected month-of-the-year effects in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index shows an irregular but recurring pattern over the long term.

H3. The frequency and strength of month-of-the-year effects in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index vary depending on the type of anomaly.

To verify the objective, wavelet analysis using Daubechies wavelets (db4) was applied. The choice of this method is justified by the non-stationary nature of financial data and the need to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends, which is difficult with classical methods of seasonality analysis. Waves enable the decomposition of a time series and the identification of patterns that may reveal episodic, cyclical or structural forms of seasonality in a changing ESG regulatory environment.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 focuses on a re-view of previous research on calendar effects, providing the theoretical background for our analysis. In

Section 3, we discussed the methodology used, including the use of wavelet analysis. We then present the results of the research along with their statistical interpretation. Finally, we summarise the results, formulate conclusions and indicate their practical implications for financial market participants.

4. Results

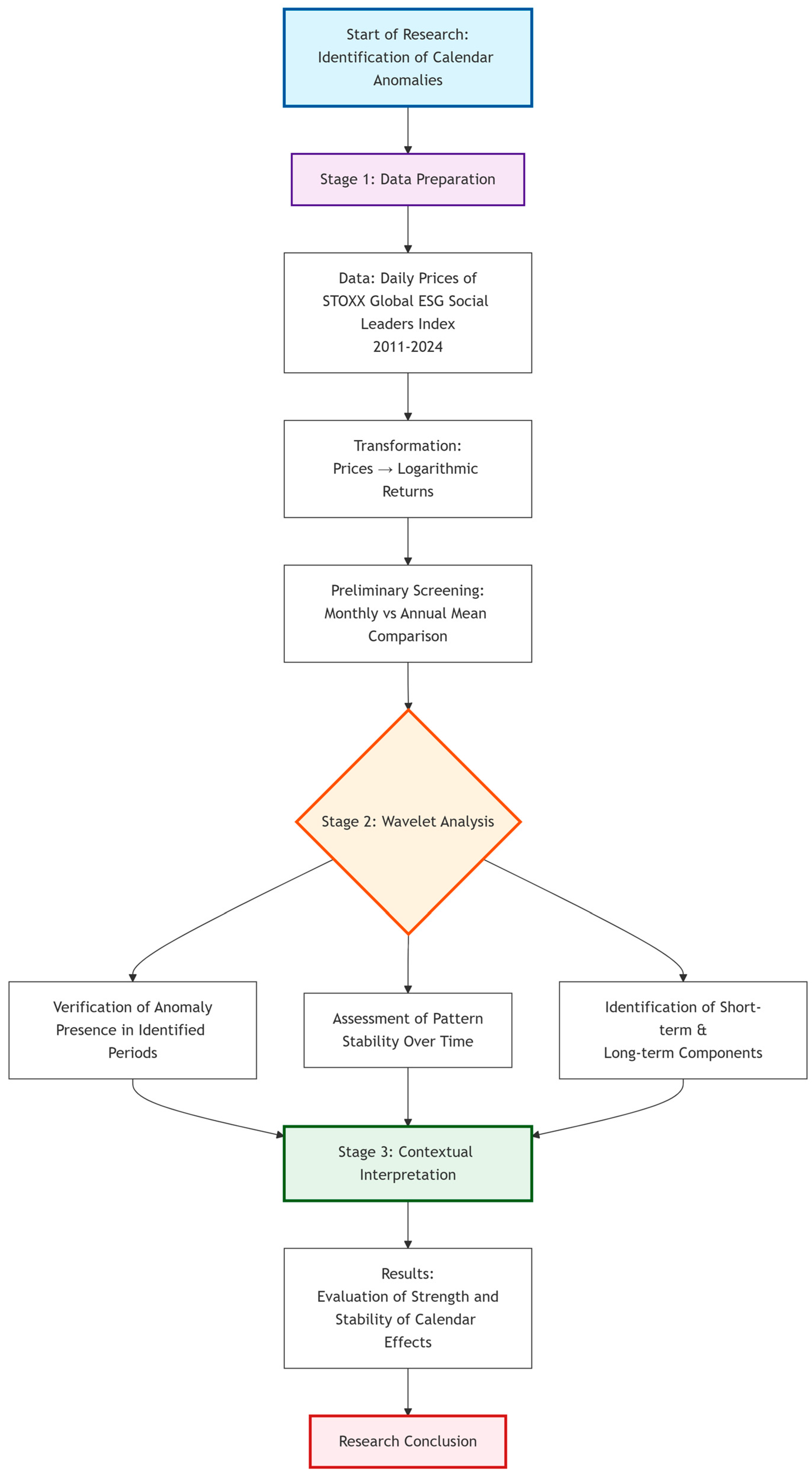

The results presented below were generated through the wavelet transformation methodology detailed in

Section 3, utilizing Daubechies db4 wavelets for multi-resolution analysis. All identified anomalies represent statistically significant deviations (

p < 0.05) from the red noise background spectrum

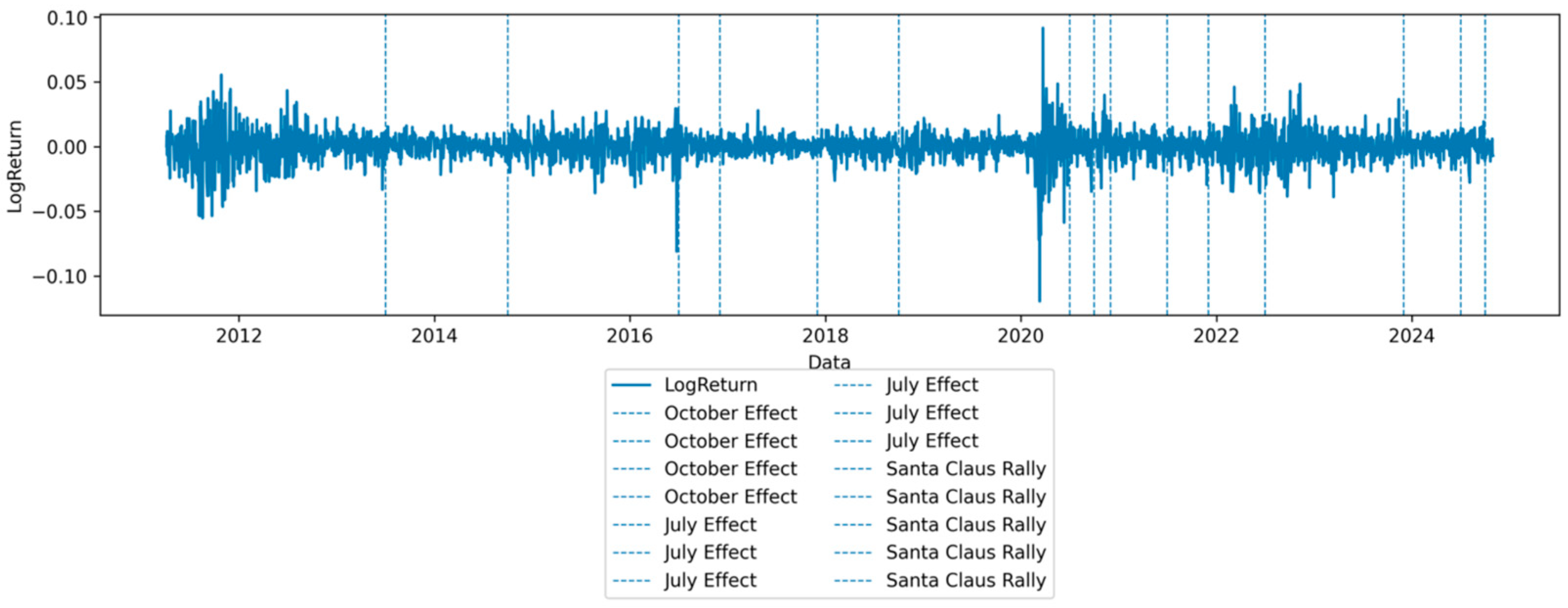

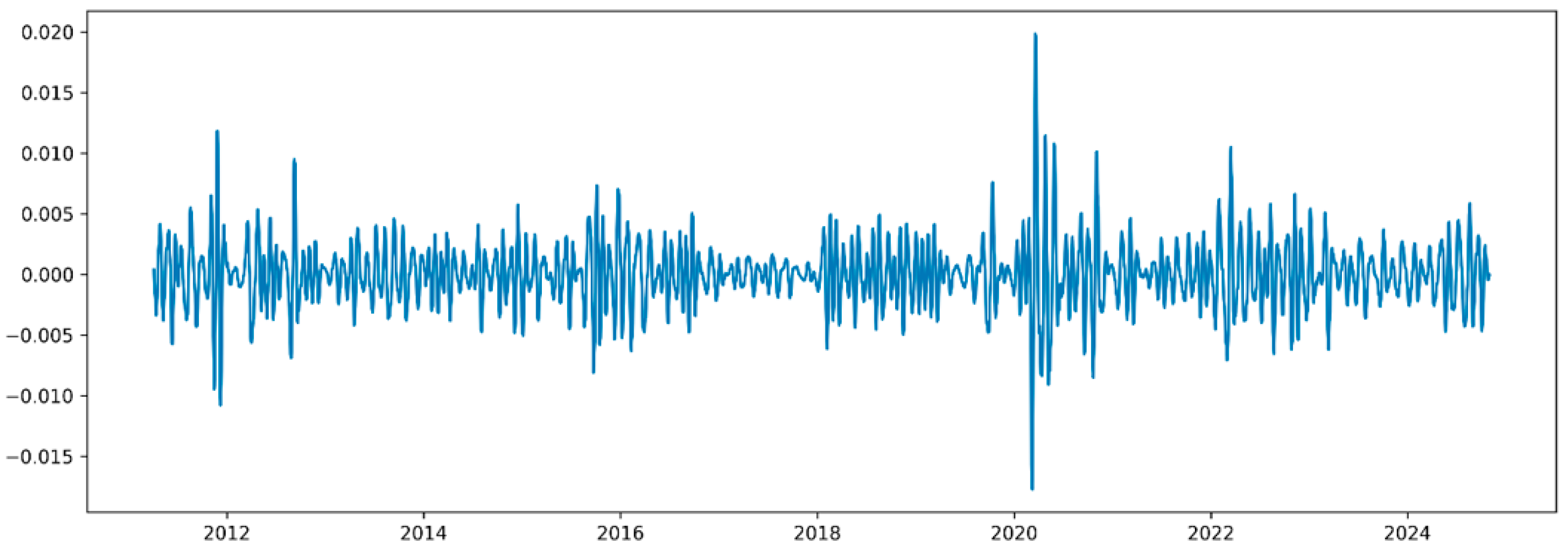

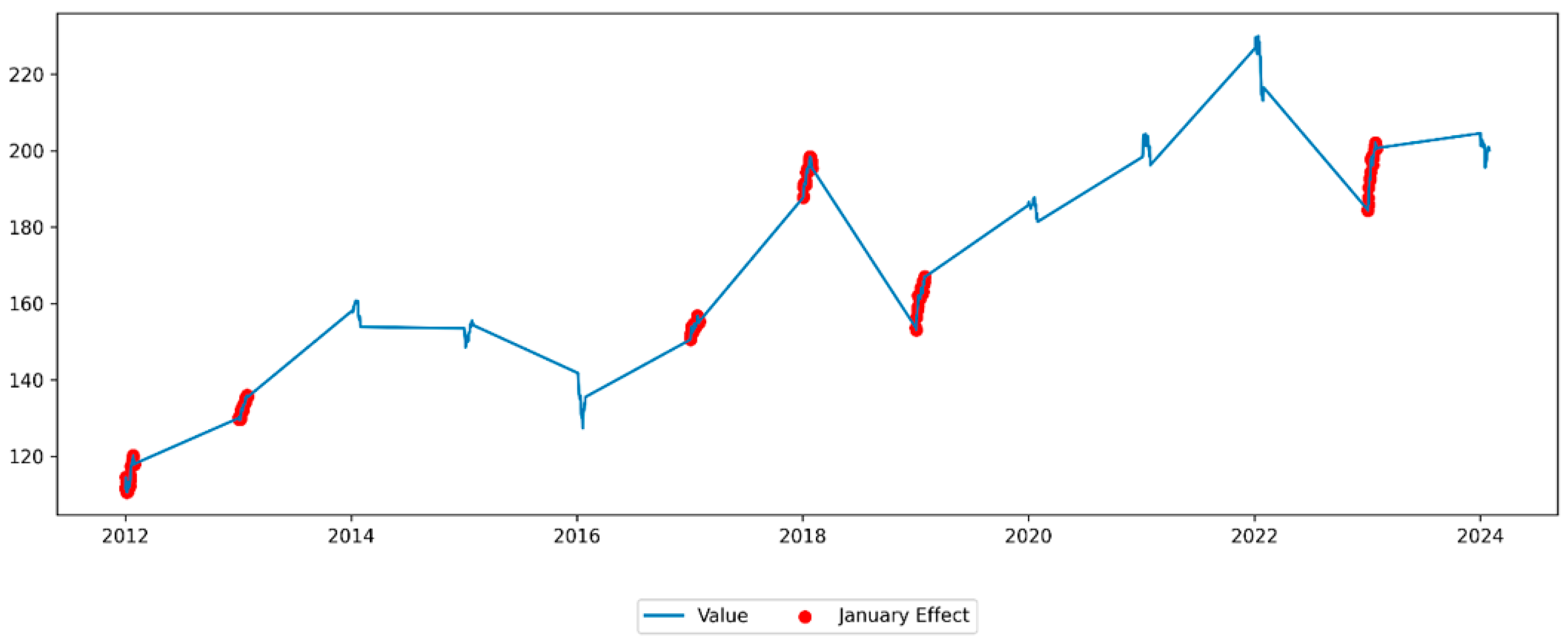

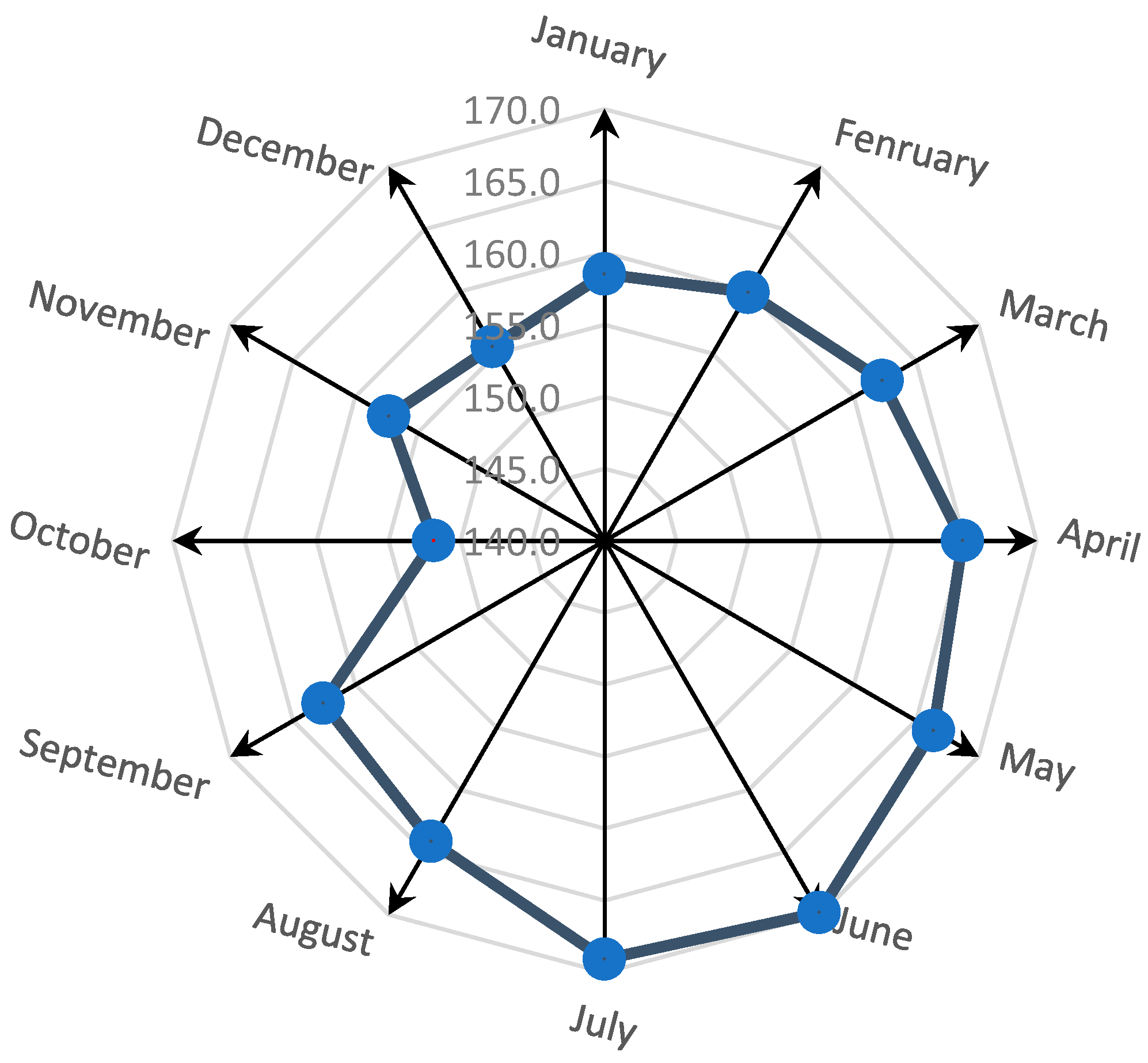

The study was conducted using wavelet transform as a research tool on the logarithmic returns of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index for the period 2011–2024 and provides insights into the presence or absence of the so-called “month-of-the-year effect.” The results clearly indicate that during the analysed period, such “month-of-the-year effects” did not occur regularly (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

The January Effect was observed during the following years of the study period: 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2023. The October Effect occurred in the years: 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2023 and 2024. The July Effect was present in the following years: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2018 and continuously from 2021 to 2024. The December Effect was identified in: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2023.

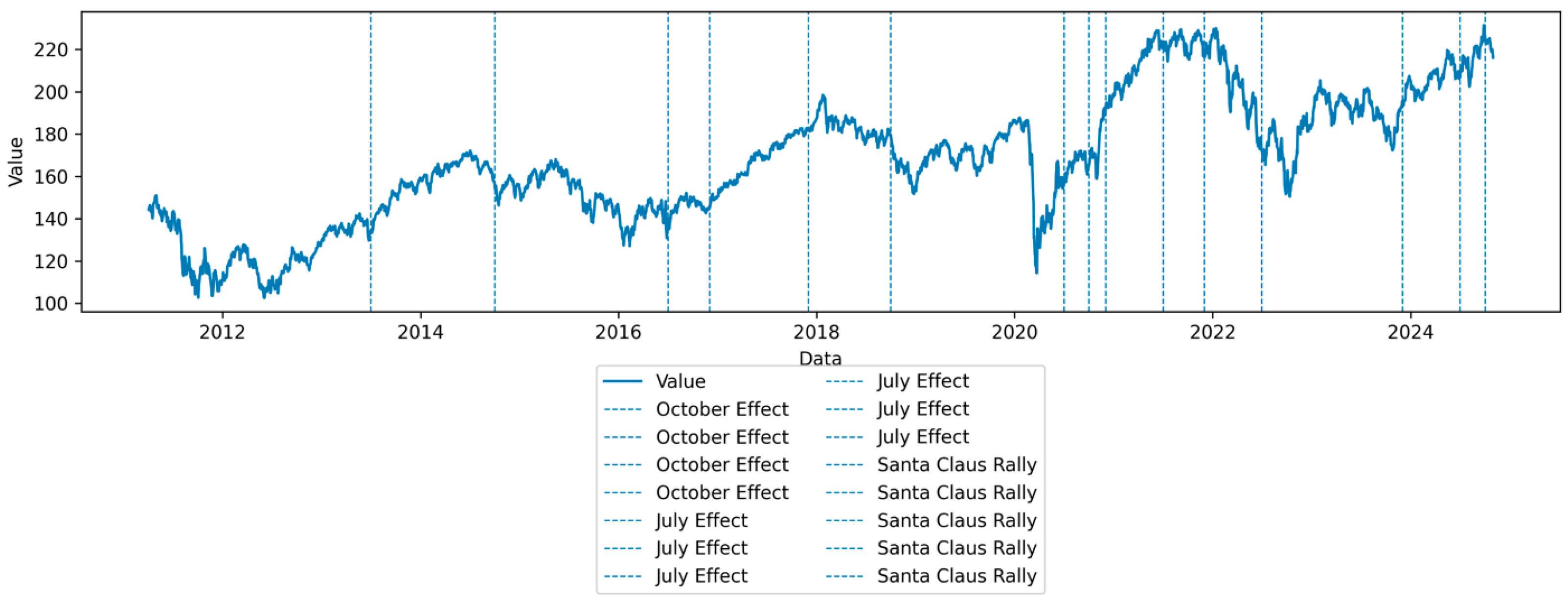

The occurrence of the so-called “month-of-the-year effects” during specific years is not coincidental. Between 2011 and 2024, the performance of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index was shaped by the growing significance of sustainable investing, accompanied by evolving investor preferences and regulatory frameworks. In the first half of the decade, the index experienced moderate development (see

Figure 1,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). However, following the adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 [

49], and with increasing public awareness of ESG investing, the index began to attract a growing volume of capital.

Research by [

50] demonstrated that, in the long term, ESG strategies generate returns that are comparable to or even exceed those of traditional equity investments. The COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2021) provided an additional boost to the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders index, as investors began to appreciate the resilience of companies with high social standards during times of crisis. According to the analysis by [

51], firms with strong ESG practices experienced smaller declines during market turmoil, which confirms the relative stability of the index during this period (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The impact of EU regulations, such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) introduced in 2021 [

52], further strengthened the position of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index by increasing the inflow of institutional capital. However, in the years 2022–2023, amid aggressive monetary tightening by central banks, the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index experienced a short-term correction. This aligns with the findings of Pedersen et al. [

53], who indicated that ESG assets may be sensitive to rising interest rates. Nevertheless, in the long term, the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index maintained its advantage over traditional benchmarks (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), supporting the thesis of a growing premium for sustainable investments [

54].

4.1. January Effect

Based on calculations for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index using wavelet transform analysis, it was found that the so-called “January Effect”—a calendar anomaly characterized by significantly higher average returns in January compared to other months of the calendar year—occurred during the following years within the analysed period: 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2023 (see

Figure 6).

The identification of this effect was based on the wavelet power spectrum analysis detailed in

Section 3.3, where statistically significant power concentrations (against an AR(1) red noise background) localized within January months were interpreted as confirmed anomalies. This methodology allows for more precise dating of the effect’s occurrence compared to traditional mean-comparison tests.

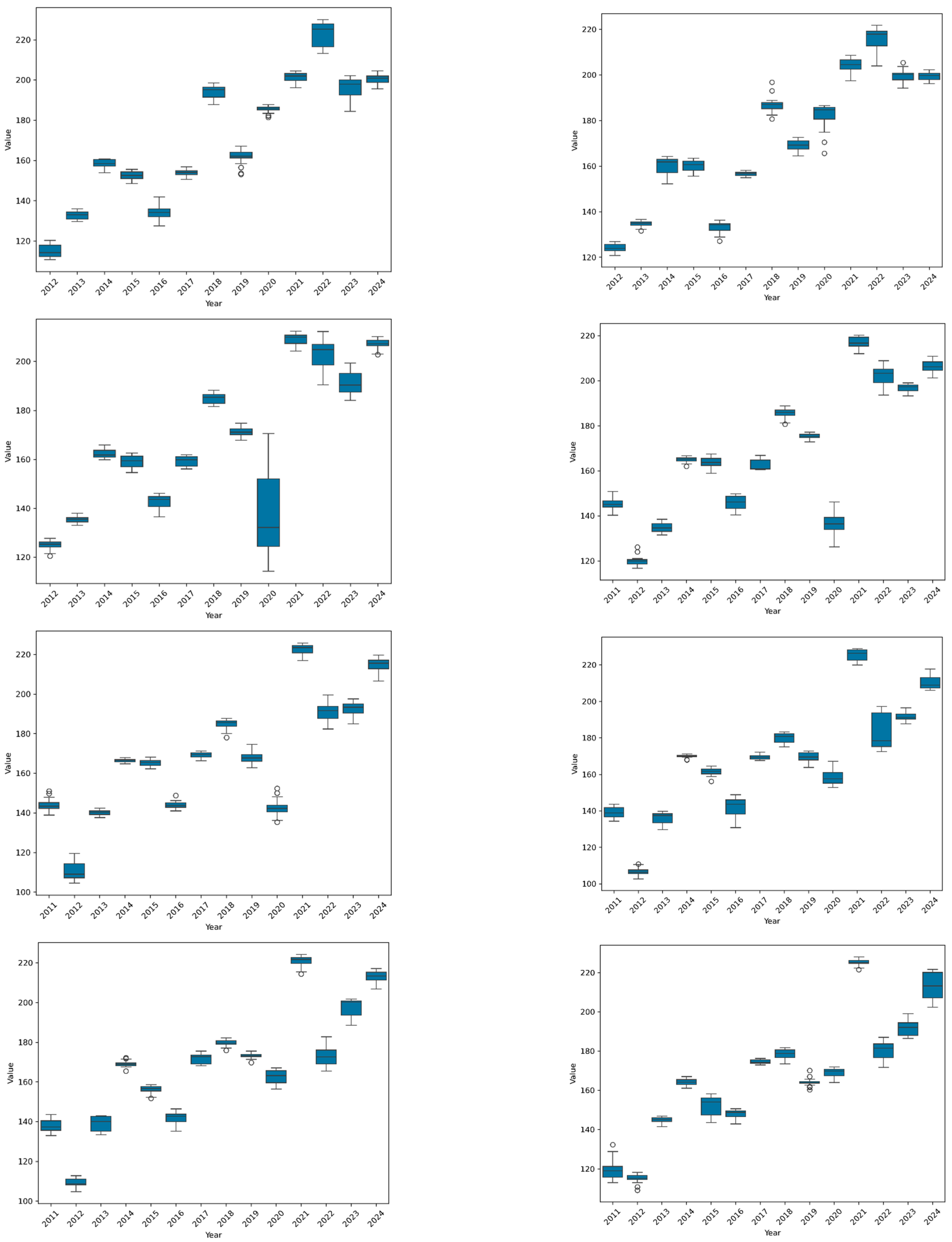

The occurrence of the “January Effect” in the indicated years may be associated with various factors. It should be noted that the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index quotations in January of each analysed year were diverse. The quartile analysis (see

Figure 7) and decile analysis of the index quotations in January from 2012 to 2024 allow for a detailed understanding of the distribution of index values across individual years.

Quartiles, which divide the data into four equal parts, reveal distinct differences in return volatility. The narrowest interquartile range (IQR) was recorded in 2020—only 1.36 points—where Q1 (185.08) and Q3 (186.44) were very close to the median (185.69), indicating an exceptionally stable period. Similarly low volatility was observed in 2017 (IQR = 1.96). On the other hand, in 2022, the IQR reached as high as 11.34 points, reflecting a significant spread between Q1 (216.49) and Q3 (227.83), with similarly high volatility noted in 2023 (IQR = 7.58). Interestingly, in 2019, despite a high standard deviation (3.77), the IQR was relatively narrow (2.83), which suggests that extreme values contributed to overall volatility. In 2016, the IQR was 3.96, while the overall range was very wide (14.44), indicating the potential presence of outliers in the lower part of the distribution.

The decile analysis (see

Table 1), which divides the data into ten parts, further deepens the understanding of the distribution of extreme values. The smallest difference between the 10th and 90th percentiles was observed in 2017 (only 4.00 points) and 2020 (4.34 points), confirming the exceptional stability during these periods. A completely different picture emerges for 2022 and 2023, where the differences between P10 and P90 amounted to 15.11 and 14.61 points, respectively, indicating significant fluctuations in the upper part of the distribution. In 2019, the 10th percentile (P10 = 156.71) was notably lower than the first quartile (Q1 = 161.22), confirming a strong left-skewness of the distribution in that year. In contrast, in 2012, the distribution was more symmetrical, with P10 at 111.11 and P90 at 119.00, with a median of 114.19. It is worth noting that in the years with the highest volatility (2022–2023), the upper deciles were particularly distant from the median, whereas in more stable years (2017, 2020), the entire distribution was concentrated within a narrow range around the central value.

This irregular pattern of occurrence—clustered in 2012–2013 and 2017–2019, but absent in intervening years—provides nuanced support for Hypothesis H2, which postulated an ‘irregular but recurring pattern’. However, the instability challenges the strong form of market seasonality and suggests the effect is contingent on specific macroeconomic and regulatory drivers, as anticipated in Hypothesis H1

The statistical analysis of returns in January across consecutive years (see

Table 2) reveals significant variation in outcomes, reflecting the specific nature of market behaviour during the first month of the year. The average rates of return exhibit considerable year-to-year volatility, with particularly high values recorded in January 2014 (158.53) and 2022 (223.49), whereas lower results were observed in January 2013 (132.92) and 2016 (134.41).

The volatility of the index quotations, measured by standard deviation, presents an interesting pattern. The most stable January quotations were observed in 2017 (SD = 1.62) and 2020 (SD = 1.68), which may suggest periods of relative market equilibrium. In contrast, exceptionally high volatility was recorded in January 2022 (SD = 6.01) and 2023 (SD = 5.70), likely reflecting market instability related to macroeconomic factors during these periods.

The coefficient of variation (CV)—calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean—confirms these observations, indicating the greatest relative stability in January 2020 (CV = 0.91) and 2017 (CV = 1.05), while the highest relative volatility occurred in January 2023 (CV = 2.91). This metric helps distinguish between years where the January Effect manifested as a stable trend versus a volatile, unpredictable surge.

Attention should also be paid to extreme values. The lowest index levels were recorded in January 2012 (110.70) and 2016 (127.41), while the highest occurred in January 2022 (230.00). Particularly noteworthy is January 2022, which, despite the highest maximum in the entire dataset, also showed a relatively low minimum (213.12) and the greatest volatility, possibly reflecting heightened market instability during that period.

The comparative analysis shows that January 2020 stood out with exceptionally low volatility and a strongly left-skewed distribution, possibly indicating specific market conditions at the beginning of that year. Meanwhile, Januaries 2022 and 2023 were characterized not only by high volatility but also by a considerable spread between the minimum and maximum returns.

From a forecasting perspective, the wavelet decomposition reveals that the January Effect’s intensity is not random but follows discernible patterns. The strengthening of the effect in years following major regulatory announcements e.g., Paris Agreement from 2015 and its attenuation during periods of monetary tightening (e.g., 2022) suggest that future occurrences could be anticipated by monitoring similar macroeconomic and regulatory catalysts, moving beyond purely historical analysis.

In summary, the occurrence of the “January Effect” in 2012 and 2013, in addition to the classic explanation—i.e., portfolio rebalancing at the beginning of the year, tax-loss selling in December and reopening positions in January—can also be interpreted as investors searching for new investment forms following the eurozone debt crisis (2010–2011). Moreover, the presence of the “January Effect” in 2017–2019 may be related to the Paris Agreement (2015) and the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. January 2017 and 2019 saw record inflows into ESG funds (according to Morningstar reports [

55]), which translated into higher returns for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders index. The “January Effect” observed in 2023 may be associated with the war in Ukraine. It is plausible that investors returned to ESG assets at the beginning of the year in anticipation of stabilization.

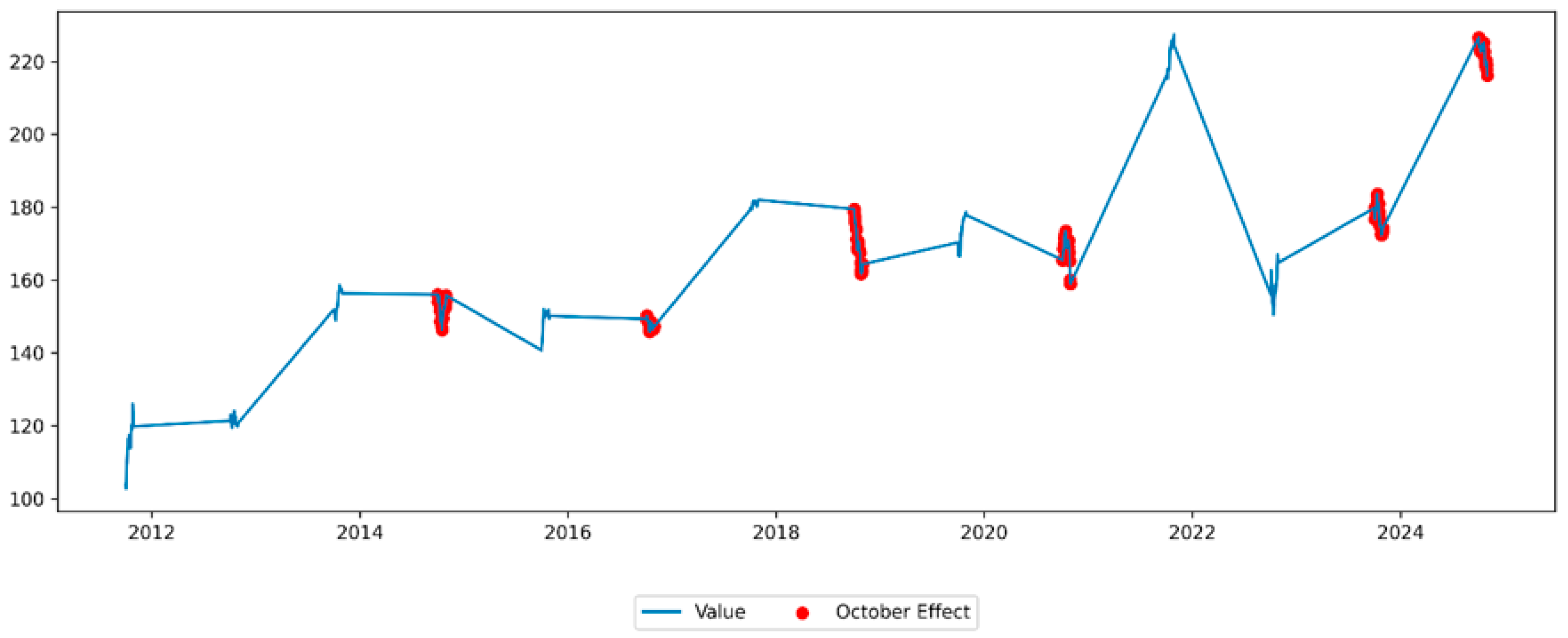

4.2. October Effect

Analysis of the results of the wavelet transform applied to the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index revealed the occurrence of the so-called October Effect (also known as the Mark Twain effect—a calendar anomaly in which October is considered the worst month in terms of returns) in the years 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2023 and 2024 (see

Figure 8). These results can be explained by macroeconomic and market-specific factors characteristic of those periods. The detection of the October Effect through wavelet analysis reveals its character as a crisis-driven anomaly rather than a consistent calendar pattern. Unlike the January Effect, its occurrence shows strong clustering around periods of significant macroeconomic uncertainty, providing direct support for Hypothesis H1 regarding the correlation with uncertainty periods.

In 2014, a marked decline in the index value was observed in October, which is characteristic of the October Effect (see

Figure 9). However, the occurrence of this effect in 2014 can be linked to two key events: the sharp drop in oil prices and the escalation of the Russia–Ukraine conflict following the annexation of Crimea [

56]. The wavelet transform recorded a significant increase in index volatility during this period, indicating strong market disruptions. A similar situation occurred in 2016, when uncertainty related to the Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential election led to heightened risk aversion among investors [

57].

The consistent pattern of the October Effect manifesting during crisis periods (2014—Ukraine conflict; 2016—Brexit; 2020—COVID-19; 2023—monetary tightening) suggests its potential utility as a forward-looking indicator. Future occurrences could be anticipated when similar macroeconomic stress indicators emerge, particularly those combining geopolitical tension with financial market uncertainty.

In 2018, another occurrence of the October Effect was observed, driven by the tightening of monetary policy by the U.S. Federal Reserve and the intensifying trade conflict between the United States and China [

58]. Notably, although the ESG index demonstrated greater resilience compared to traditional benchmarks, the wavelet analysis revealed a distinct anomaly in October’s trading activity.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 created exceptional market conditions. The second wave of infections in October, accompanied by renewed restrictions, contributed to a decline in the index’s value, despite the generally strong performance of ESG companies throughout the pandemic [

59]. The wavelet transform confirmed a typical October Effect pattern during this time.

The phenomenon resurfaced in 2023 and 2024, which can be linked to persistently high interest rates and fears of a recession within the Eurozone [

60]. The wavelet analysis for these years revealed a characteristic increase in amplitude during October, indicating heightened volatility consistent with the historical pattern of the October Effect.

These findings align with prior research on market seasonality. As noted by [

61], the October Effect tends to be especially pronounced during periods of heightened macroeconomic uncertainty. However, it is worth emphasizing that in the case of ESG indices, this effect may manifest itself in a somewhat attenuated form due to their unique investment profile [

62].

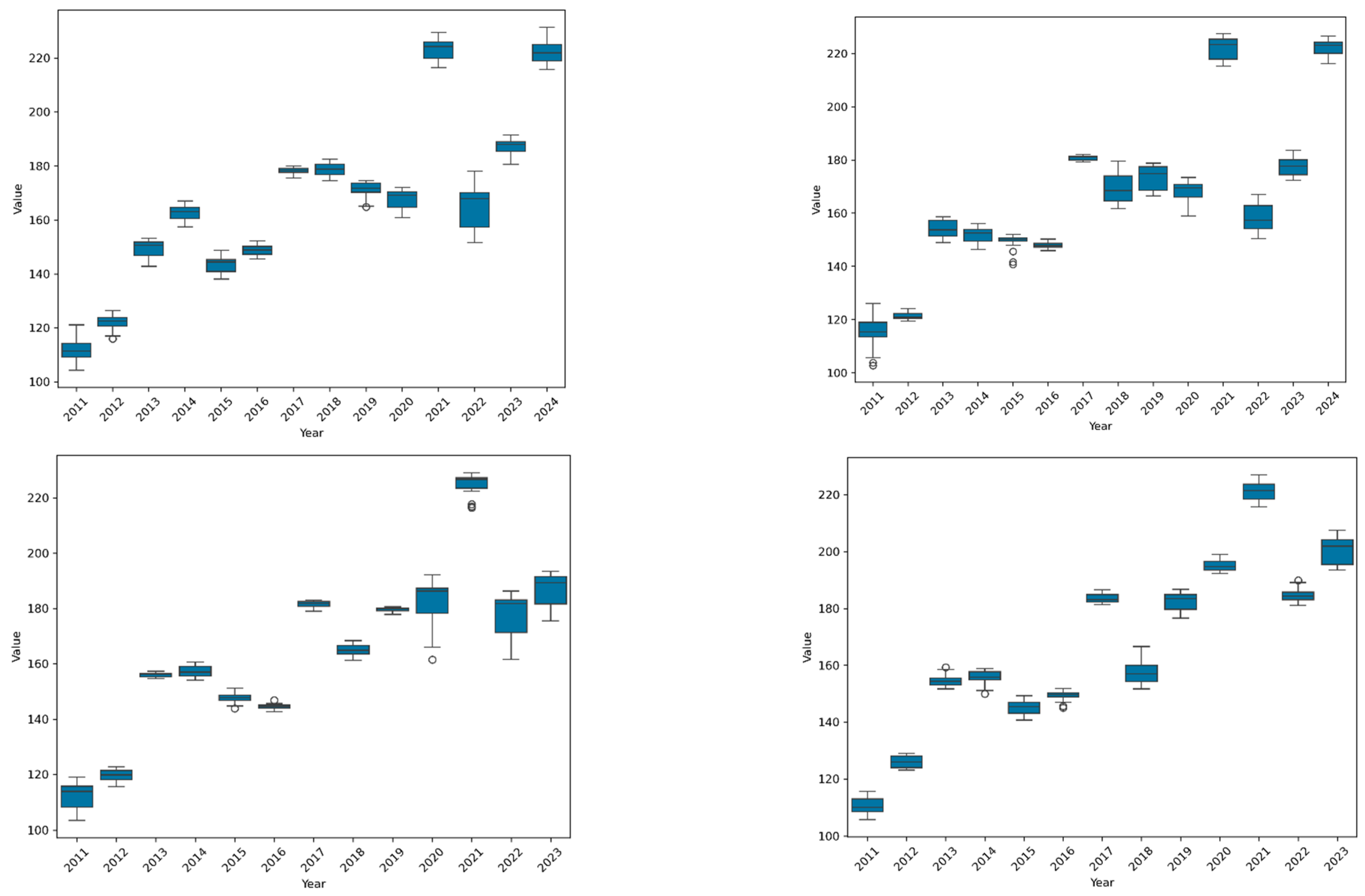

Statistical analysis of October returns for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index from 2011 to 2024 reveals clear patterns in the distribution of returns during this specific month. The wavelet transform identified the presence of the effect in 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2023 and 2024, which is corroborated by basic descriptive statistics.

In years marked by the October Effect, there is a noticeable increase in return volatility, as measured by both the standard deviation and the coefficient of variation (CV). For instance, in 2018, the standard deviation reached 5.66 with a CV of 3.34; in 2020, 4.15 and 2.47, respectively; and in 2023, 3.54 and 1.99. By contrast, in years without the effect (e.g., 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019), volatility was significantly lower, with standard deviations not exceeding 3.17 and CVs ≤ 2.05. One exception is 2011, which, despite not being classified as a year with the effect, showed high volatility (SD = 6.16, CV = 5.35), likely due to market instability following the global financial crisis. The wavelet power spectrum analysis (db4) used for identification captures not only the presence but also the intensity and duration of these October anomalies. The significant increase in return volatility during effect years, as measured by standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV), corresponds to distinct, localized peaks in the wavelet power spectrum concentrated specifically in October months.

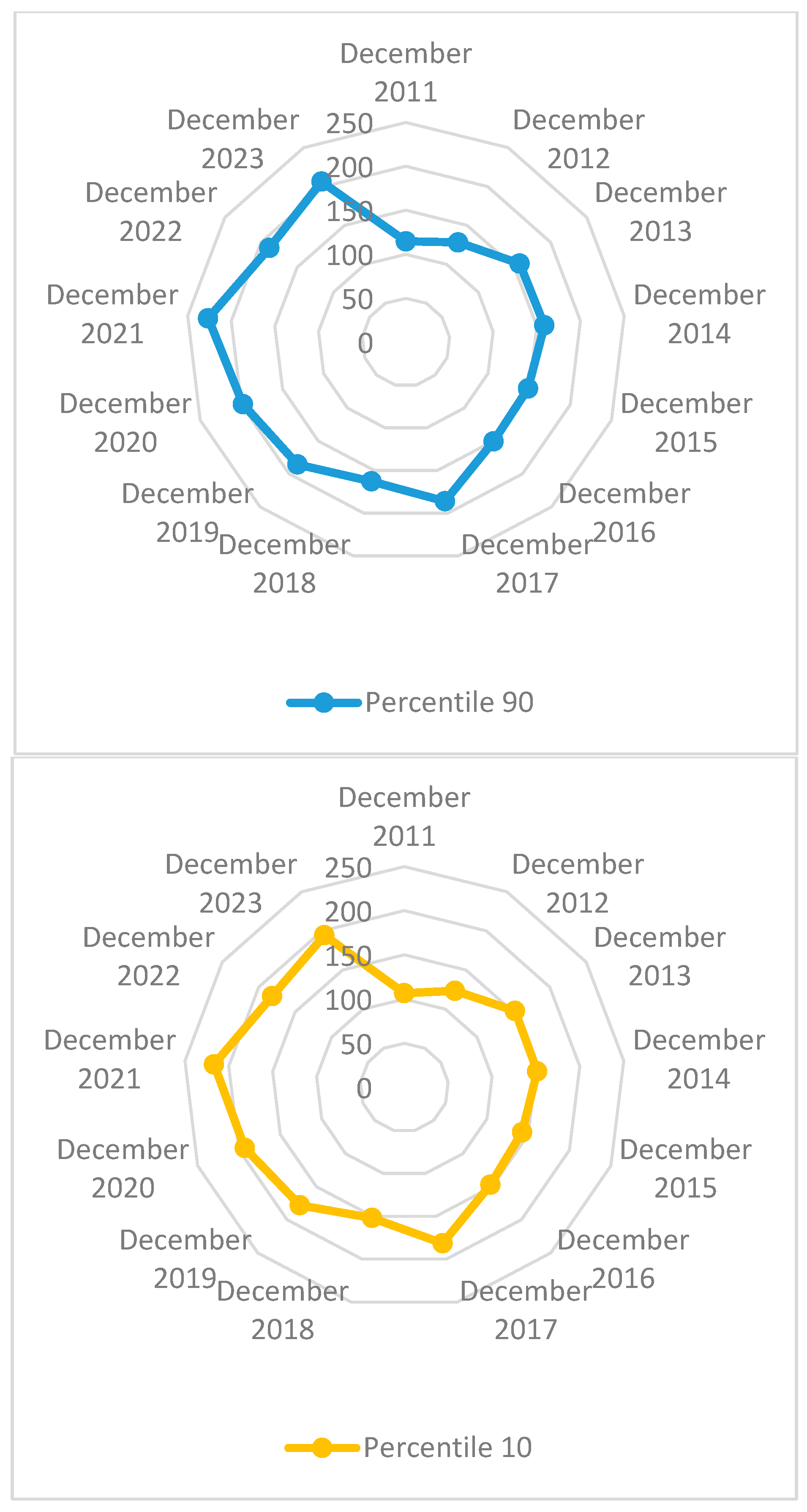

Analysis of positional measures confirms a greater spread in returns during years with the effect. The interquartile range (IQR) in these years averaged 5.30 points, while in years without the effect it was only 2.15 points. Particularly notable are the percentile spreads—on average, the difference between the 90th and 10th percentiles was 9.23 points in effect years, compared to just 3.67 points in other years. This wider distribution range likely reflects greater investor uncertainty and elevated trading activity typical of October.

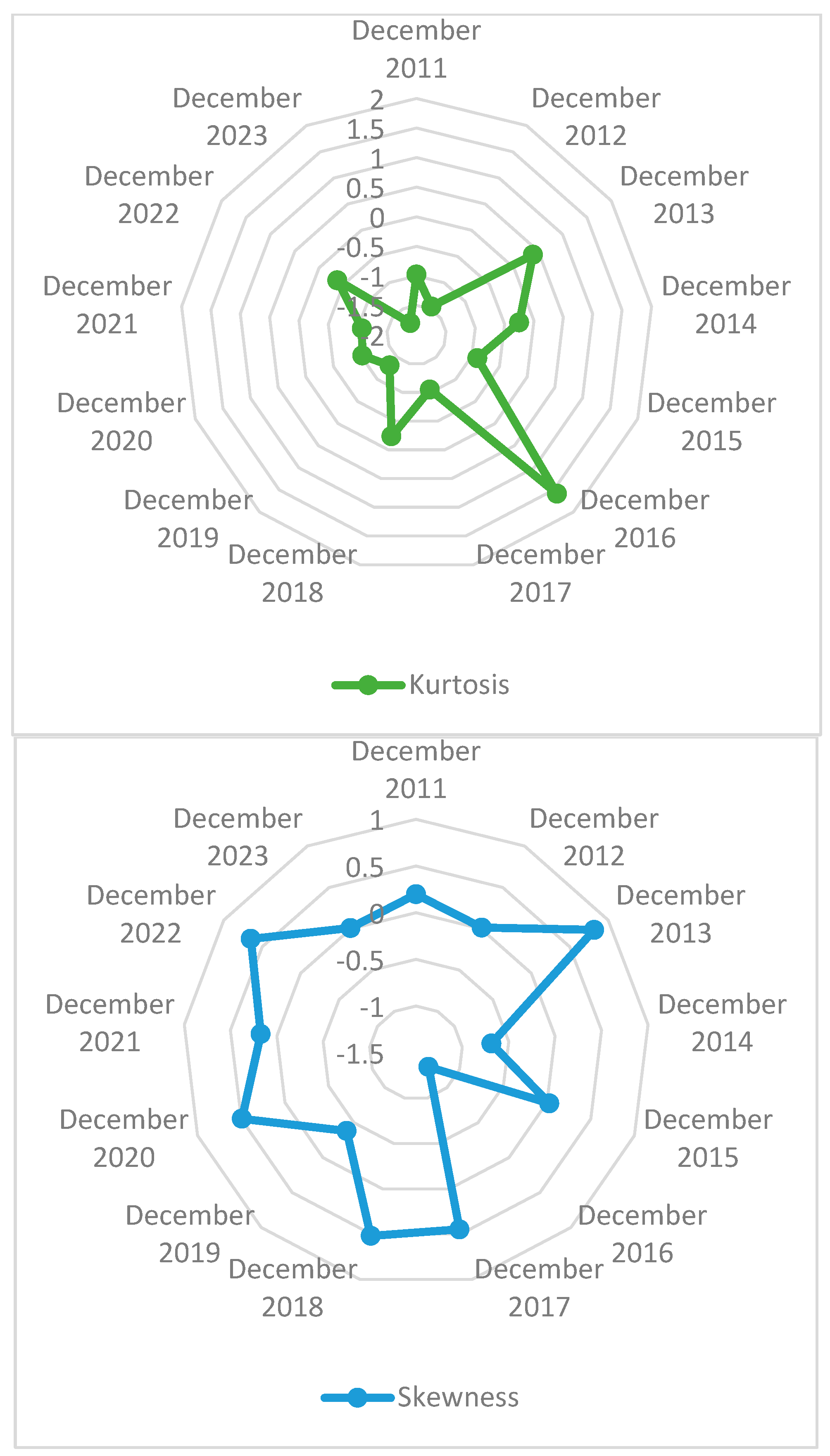

Interesting insights emerge from the analysis of distribution shape. In years affected by the effect, returns tend to be negatively skewed (average skewness = −0.46), suggesting more frequent values below the median—a hallmark of downward seasonal anomalies. Kurtosis in these years also varies more widely (from −1.54 to 0.74), indicating fluctuations in distribution concentration. In years without the effect, skewness is closer to zero (average −0.10), and kurtosis is more stable and predominantly negative, pointing to flatter distributions.

From the perspective of ESG modelling, it is particularly noteworthy that even in years when the October Effect occurred, the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index exhibited certain features of stability. Minimum values during these years rarely fell below 145 points (with the exception of 2020, where the minimum was 158.96), whereas traditional indices often experienced sharper declines. This may suggest that ESG factors serve a buffering role, limiting extreme downturns even in periods of increased market volatility.

The evolution of the effect over time is also worth noting. In recent years (2020, 2023, 2024), despite the persistence of elevated volatility typical of the October Effect, the mean and median index values have steadily increased—from 168.10 in 2020 to 222.40 in 2024. This trend may reflect the overall appreciation of ESG indices over the past decade, which partially offsets the traditional October market weakness.

From an investment strategy perspective, the findings suggest that the October Effect in ESG indices is more moderate than in traditional benchmarks. While the effect is statistically detectable, its impact appears to be mitigated by the fundamental resilience of high-rated ESG companies to extreme market movements. At the same time, the consistent rise in volatility during October may create opportunities for strategic rebalancing of ESG portfolios.

The episodic nature of the October Effect, entirely absent in stable years yet pronounced during crises, offers partial validation of Hypothesis H3 regarding variation by anomaly type. Its manifestation as a ‘crisis anomaly’ distinct from more stable calendar effects like July suggests that predictive models for ESG indices should incorporate anomaly-type-specific drivers rather than treating all seasonal effects uniformly.

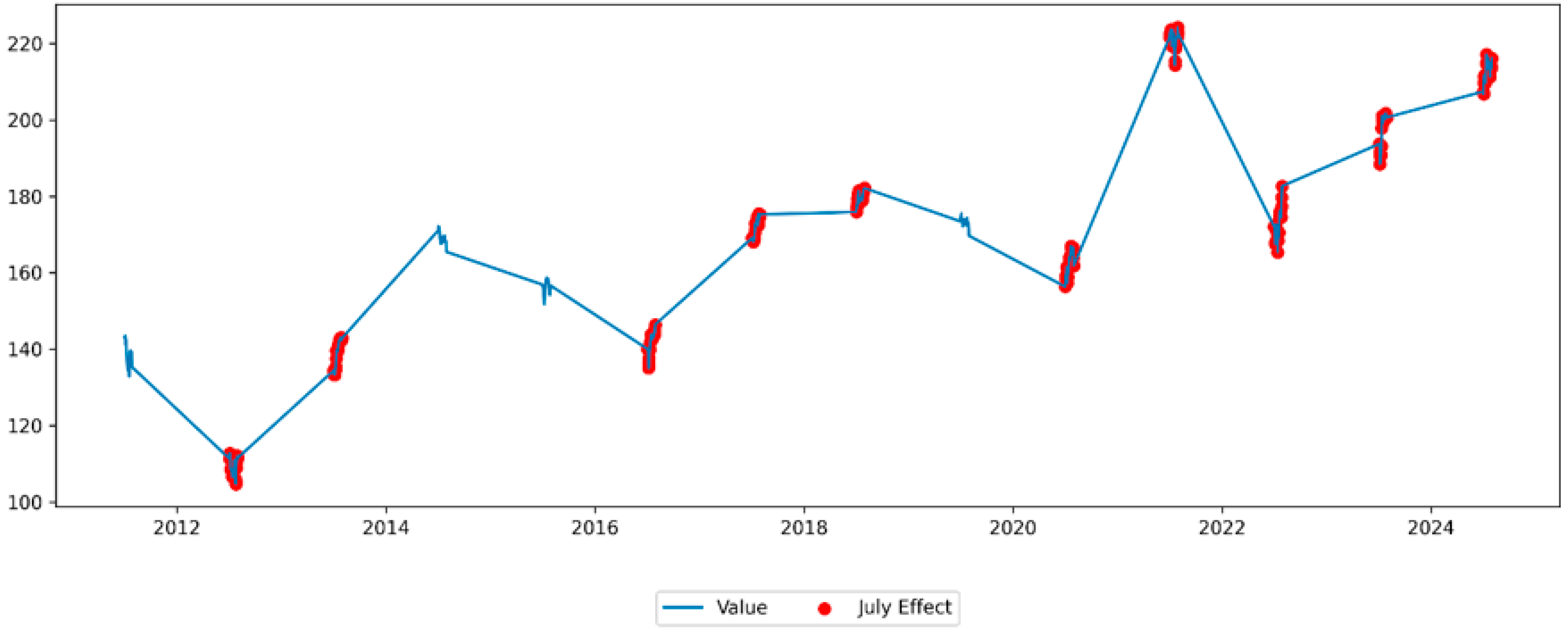

4.3. July Effect

The “July Effect” refers to the tendency for stock indices to exhibit increased returns during the summer months, particularly in July. In the analysed period, this phenomenon was observed for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index in the following years: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2021–2024 (see

Figure 10).

The wavelet analysis reveals a distinct evolutionary pattern for the July Effect. Its manifestation has shifted from sporadic occurrences in the earlier part of the sample (2012–2013, 2016–2018) to a period of sustained and strengthening presence in recent years (2021–2024). This increasing stability, captured by the growing consistency of significant wavelet power in July, suggests a structural change in summer market dynamics for ESG assets, potentially linked to their mainstream adoption and the seasonality of institutional capital flows.

Statistical analysis of the July quotations for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index over the period 2011–2024 reveals important insights into the interaction between market seasonality and ESG factors. The data indicates that the so-called “July Effect”—i.e., the tendency for higher returns in July—occurred in 2012, 2013, 2016–2018 and 2021–2024, thus supporting the seasonality hypothesis, albeit with notable variability in the strength and nature of the phenomenon.

A key finding is that the years exhibiting a pronounced July Effect were typically characterized by higher mean index values (e.g., 221.73 in 2021) alongside moderate volatility (standard deviation of 2.50 in 2021), suggesting that ESG factors may play a stabilizing role during periods of typical seasonal appreciation. Analysis of positional statistics for the July quotations of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index in the years 2011–2024 reveals significant relationships between the occurrence of the “July Effect” and the distributional characteristics of index values. In the years with a confirmed presence of the effect (2012, 2013, 2016–2018, 2021–2024), noticeably wider interquartile ranges (Q3–Q1) are observed compared to years without the effect. Conversely, significant variability was observed in years without the effect—e.g., in 2014, a relatively high mean value (168.86) was recorded alongside exceptionally low standard deviation (1.55), which may reflect the influence of macroeconomic factors suppressing expected seasonal patterns.

The distribution of returns demonstrates pronounced leptokurtosis in years with a strong July Effect (e.g., 2019, 2021), which—within the framework of ESG investment models—can be interpreted as increased investor concentration around consistent sustainable development strategies during the summer months. At the same time, the predominance of negative skewness in most years suggests that even during periods of appreciation, there remains an elevated likelihood of short-term declines. This may be attributed to the inherent characteristics of ESG investments, such as lower liquidity or higher sensitivity to qualitative factors.

Analysis of positional statistics for the July quotations of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index in the years 2011–2024 reveals significant relationships between the occurrence of the “July Effect” and the distributional characteristics of index values. In the years with a confirmed presence of the effect (2012, 2013, 2016–2018, 2021–2024), noticeably wider interquartile ranges (Q3–Q1) are observed compared to years without the effect. This is particularly evident in 2013 (7.47 points), 2016 (3.85 points), and 2023 (7.24 points), whereas years without the effect are characterized by exceptionally narrow interquartile spreads, such as in 2014 (1.36 points) and 2019 (1.12 points). This pattern suggests that the July Effect manifests itself not only through changes in average price levels, but more importantly through shifts in the structural distribution of prices during the analysed month (

Table 3).

Of particular interest is the position of the median (Q2) relative to the other quartiles. In years with a pronounced seasonal effect, the median tends to be closer to the third quartile (Q3), indicating left-skewed distributions and a more frequent occurrence of values above the median. This phenomenon is especially evident in 2013, 2016, 2017 and 2021–2023. Such distributional characteristics may reflect a typical seasonal “growth tension” mechanism, wherein increased demand during a specific period leads to a concentration of prices in the upper ranges of the distribution. It is worth noting that in 2014 and 2019—years without the effect—the distributions were much more symmetrical, with the median positioned almost exactly at the centre of the interquartile range.

Analysis of the 10th and 90th percentiles provides additional important insights. In the years when the July Effect was present, the difference between the 90th and 10th percentiles was significantly greater (e.g., 9.15 points in 2013, 10.34 points in 2023) than in the years without the effect (e.g., 3.78 points in 2014, 2.13 points in 2019). This increased dispersion suggests greater heterogeneity in price behaviour during periods of seasonal effects, potentially resulting from the varying responses of portfolio components to the factors driving the July Effect. Moreover, in most cases, both the 10th and 90th percentiles are distinctly higher in years with the effect compared to adjacent years without it, reinforcing the hypothesis of a general upward shift in the distribution during periods when the phenomenon occurs.

The evolution of these indicators over time reveals a marked strengthening of the July Effect in recent years (2021–2024). During this period, we observe not only higher absolute values for all positional measures, but also increased interquartile and interpercentile spreads. From the perspective of ESG modelling, these findings suggest that seasonality in socially responsible indices manifests itself in a distinctive manner, differing from typical patterns observed in conventional benchmarks. This observation may correlate with the growing popularity of ESG investing and the increasing attention from institutional investors to ESG-related indices. Notably, even within years where the effect was present, the intensity of its impact varied—for example, the effect in 2012 was relatively weak (interquartile range of 2.85 points), whereas in 2023 it was particularly pronounced (

Table 4).

The broader value distributions in years with the effect may reflect a more complex valuation mechanism, wherein ESG factors modify traditional seasonal dynamics. At the same time, the exceptionally narrow interquartile ranges in certain years (e.g., 2014, 2019) indicate that under specific macroeconomic conditions, the fundamental characteristics of sustainable investments may entirely overshadow calendar-based effects. These observations have important implications for seasonality-based investment strategies, pointing to the need to incorporate additional fundamental filters when constructing ESG portfolios during the summer months.

In summary, the application of the db4 wavelet transform has been particularly effective in characterizing the July Effect’s unique trajectory. The results provide strong, multi-scale evidence for Hypothesis H2 regarding long-term, recurring patterns, as the effect shows a clear trend towards stabilization. Its behavior aligns with the influence of structural factors mentioned in Hypothesis H1, such as the growing seasonal reallocation of capital into sustainable assets, rather than being solely driven by transient macroeconomic uncertainty.

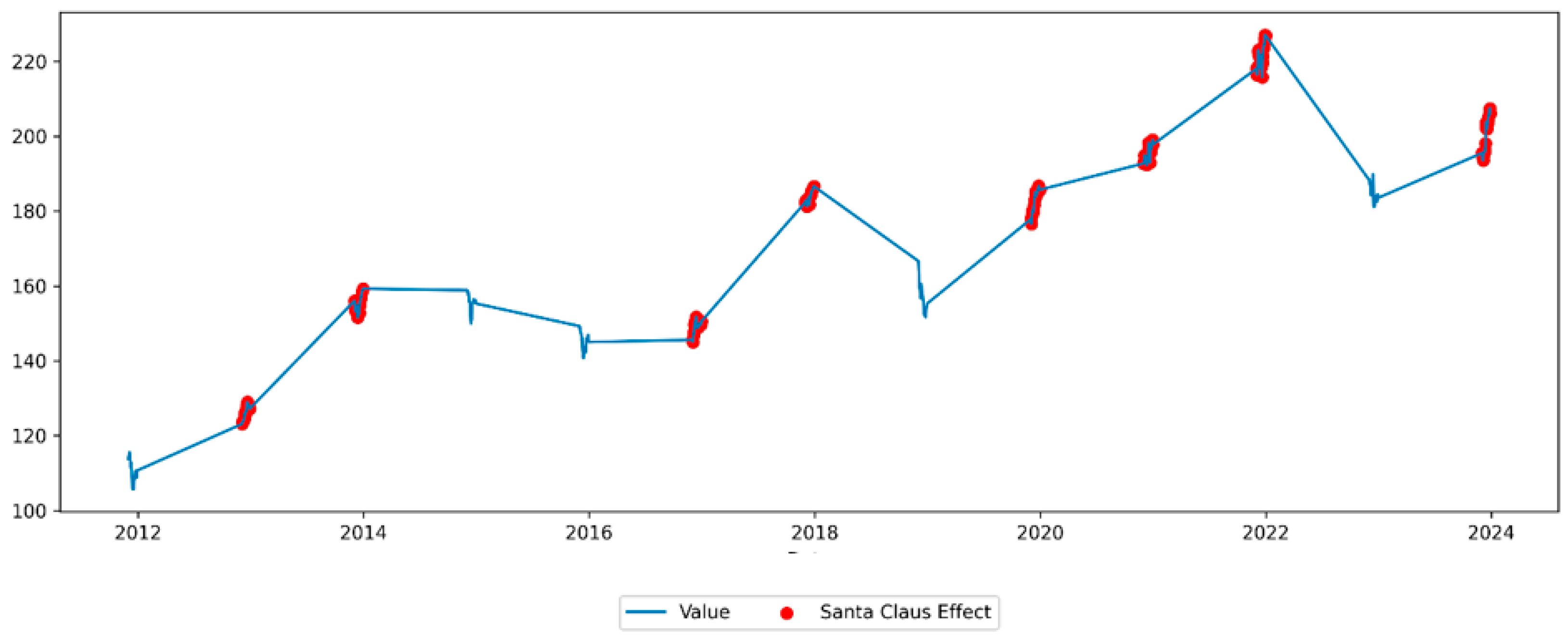

4.4. December Effect

The results of the analysis indicating the presence of the so-called “December Effect” in the years 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2023 for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index are explained by a range of macroeconomic, market-related and ESG-specific factors.

The identification of this effect via wavelet analysis highlights its dual nature: it is the most frequently occurring anomaly in our study, yet its manifestation is consistently modulated by external factors. The db4 wavelet transform was particularly effective in isolating the specific, short-term surge in power associated with the traditional ‘Santa Claus Rally’ period from the broader December market dynamics (

Figure 11).

In the years 2012–2013, favourable market conditions were observed, associated with the quantitative easing (QE) policies implemented by major central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank [

63]. The liquidity influx into the market and the traditional end-of-year rally contributed to the increase in the index value, with companies meeting ESG criteria additionally benefiting from the growing investor interest in sustainable strategies.

In 2016, the “December Effect” effect appeared after a period of heightened volatility related to the Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential elections. The year-end upward momentum was partially driven by renewed market optimism and by institutional investors increasing their allocations to ESG assets as part of annual portfolio rebalancing [

64,

65].

The years 2017 and 2019 were characterized by a strong upward trend in equity markets, driven by solid economic performance and the advancing institutionalization of ESG investing. In December 2017, the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index rose by 4.2%, partly due to expectations surrounding the implementation of the Paris Agreement [

66]. In 2019, an additional factor supporting the year-end rally was the European Commission’s adoption of the Action Plan on Sustainable Finance, which further directed capital flows toward companies meeting social (S) criteria.

The period of 2020–2021 saw a particularly pronounced “December Effect,” attributable to a combination of factors. In December 2020, markets were recovering from previous pandemic-induced declines, and investors increasingly perceived ESG companies as more resilient to crises [

51]. In 2021, a further stimulus came from the entry into force of the first phase of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which imposed greater transparency requirements on financial institutions regarding sustainable investments.

In 2023, the index recorded a December increase despite prior recession concerns, driven by improved investor sentiment following announcements of monetary policy easing by the Fed and the ECB [

60]. Additionally, capital inflows into ESG funds intensified toward year-end in anticipation of new regulatory requirements related to sustainability reporting (CSRD).

It is worth noting that in some years (e.g., 2014, 2015, 2018, 2022), the “December Effect” either did not occur or was barely noticeable. In 2014 and 2015, this was due to falling oil prices and economic uncertainty within the Eurozone, while in 2018 and 2022, sharp interest rate hikes played a decisive role, dampening risk appetite even during a seasonally favourable period [

61].

Statistical analysis of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index performance in December between 2011 and 2023 allows for meaningful conclusions to be drawn regarding the occurrence of the “December Effect”—a phenomenon that traditionally refers to a rise in stock prices during the last week of December and the first week of January. The data reveals significant differences in statistical characteristics between the years in which the phenomenon was observed (2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2019–2021, 2023) and those in which it was absent.

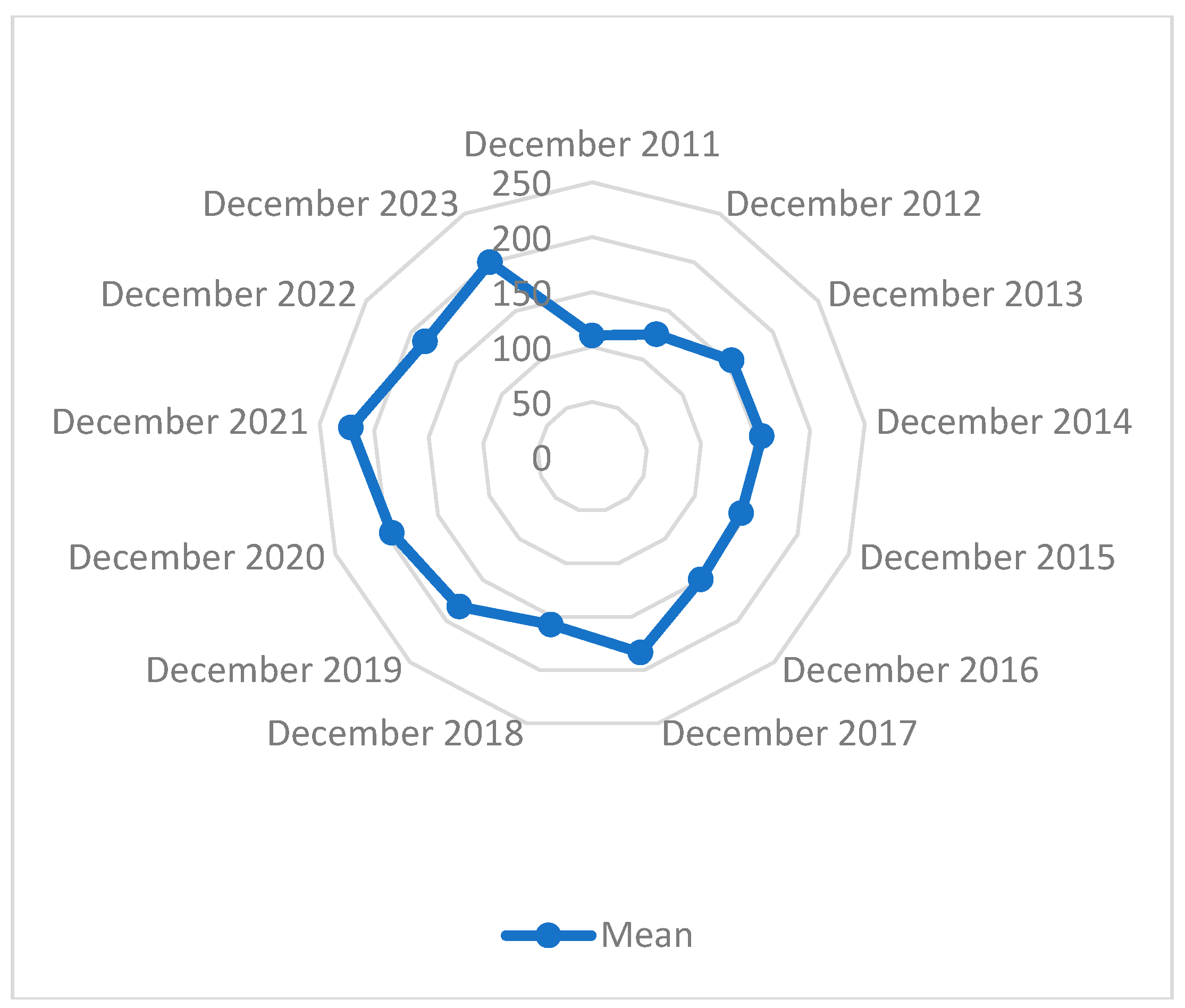

In the years marked by the “December Effect,” higher mean and median values were recorded compared to the years without the effect, with particularly distinct differences during the 2019–2023 period (see

Figure 12). Average index values in December during years with the rally ranged from 125.92 points (2012) to 221.37 points (2021), whereas in the years without the effect (2011, 2014, 2015, 2018, 2022), the values were significantly lower—for example, 110.40 points (2011) or 145.21 points (2015).

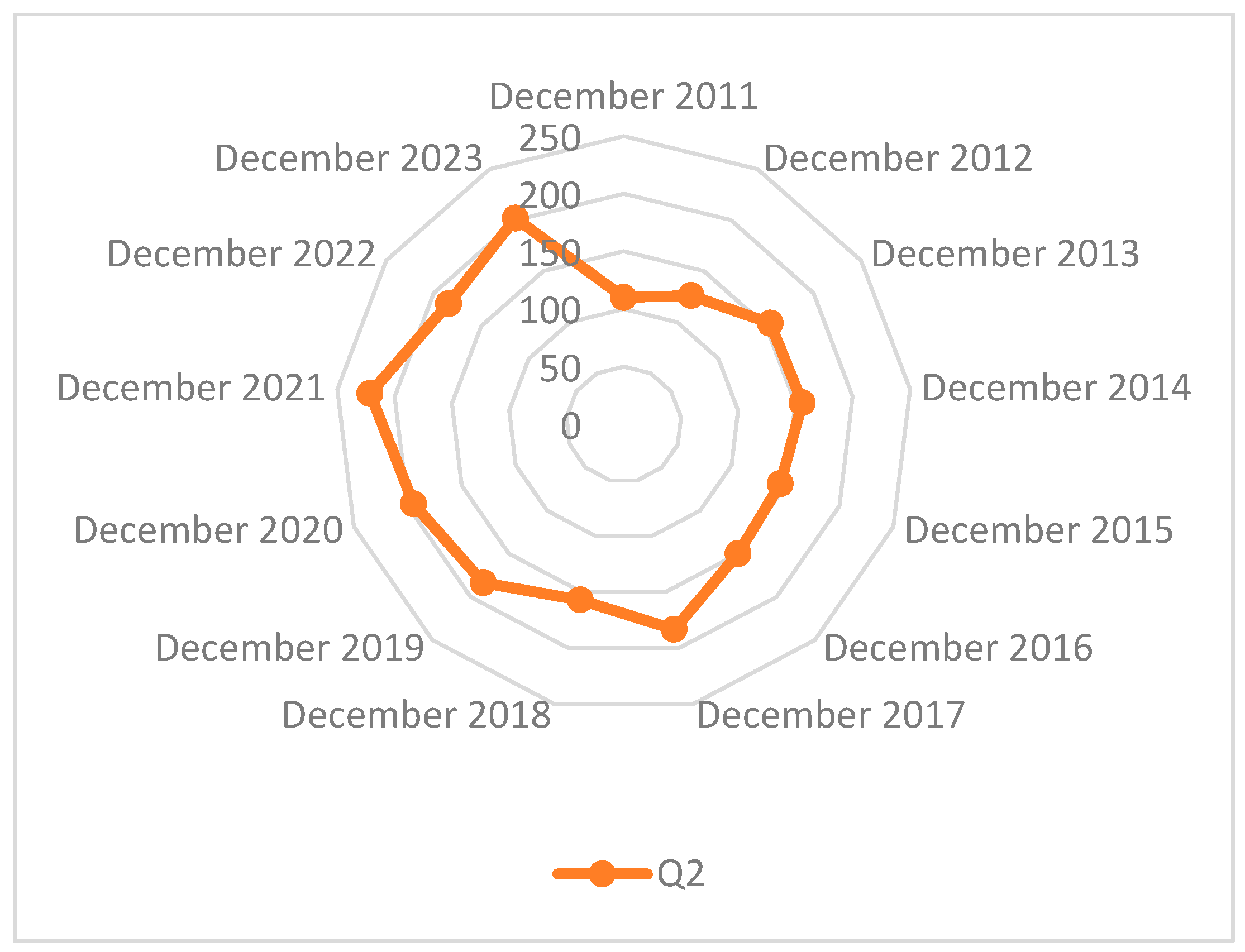

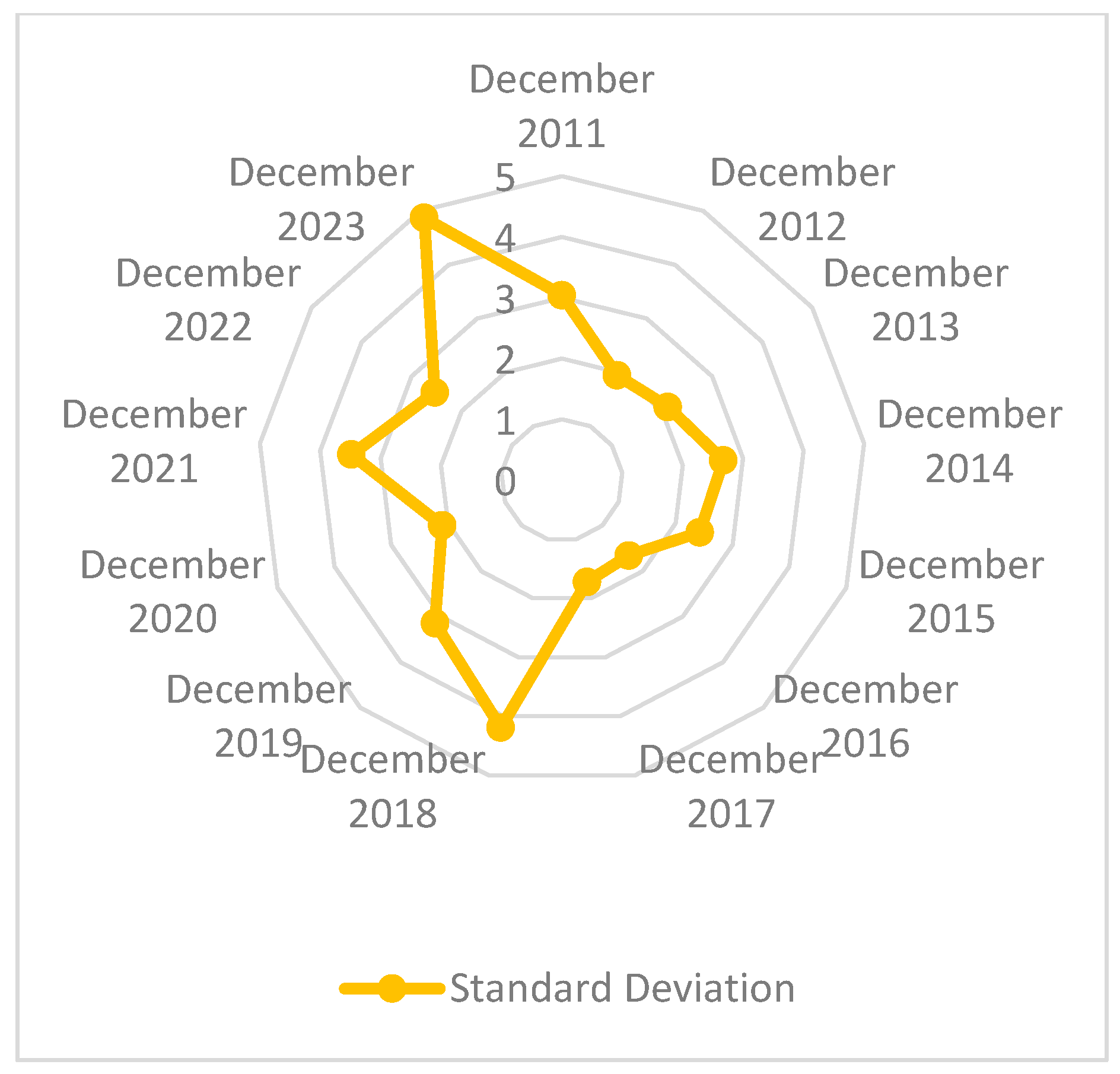

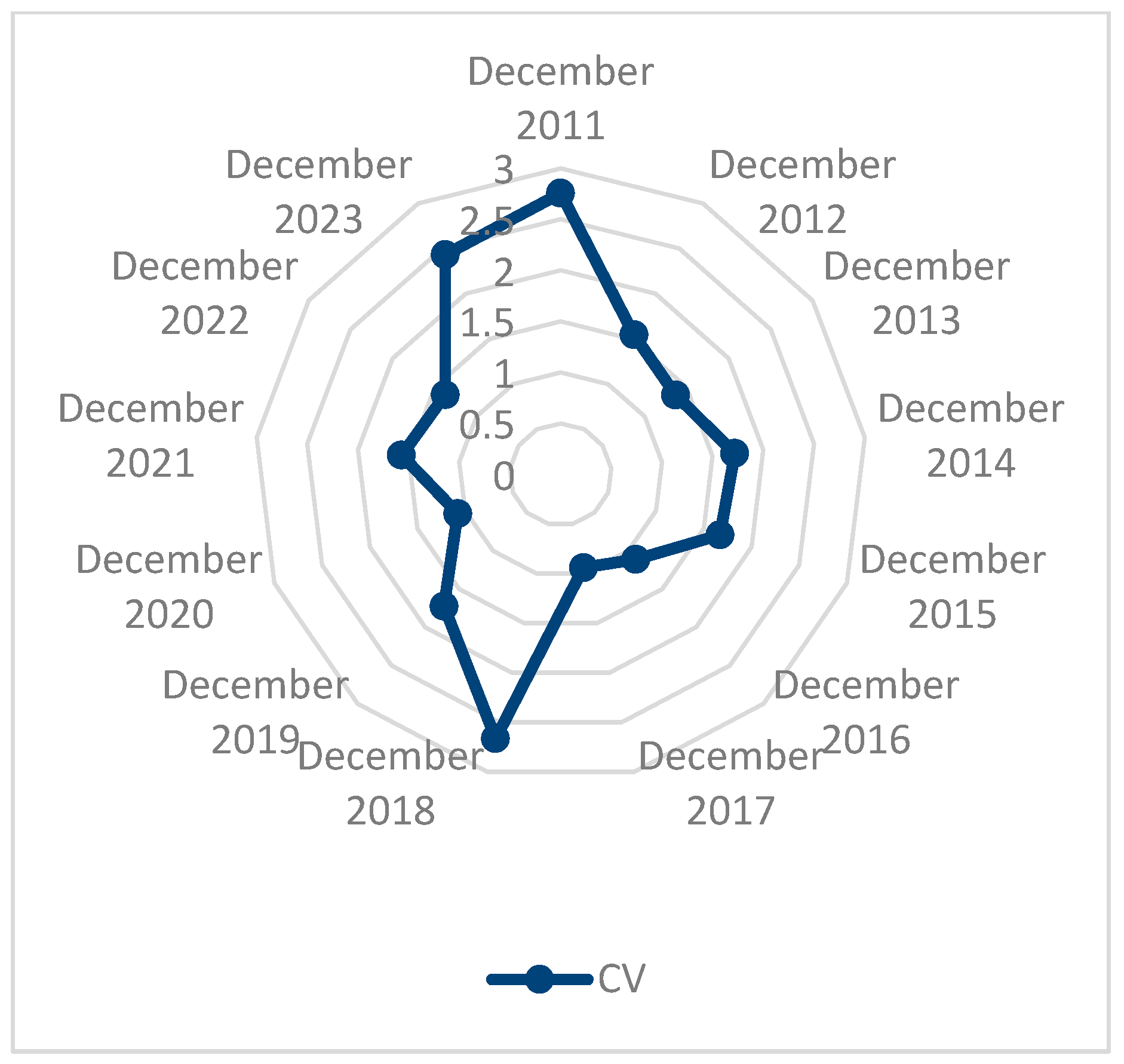

A characteristic feature of the years marked by the “December Effect” is relatively low price volatility, measured by the standard deviation, which in most cases did not exceed 3 points (with the exception of 2023, when the standard deviation reached 4.87 points). The coefficient of variation (CV) in these years generally remained in the range of 1.0 to 1.5, indicating stable price behaviour during the analysed period (

Figure 13).

In contrast, during the years without the effect (e.g., 2018 and 2022), significantly higher volatility was observed—up to 4.19 points in 2018—with a CV of 2.66, suggesting greater market uncertainty and less consistent investor behaviour.

Analysis of positional measures revealed significant differences in the distribution shape of index values. In years when the “December Effect” occurred, the interquartile range (IQR) was generally narrower—for example, 1.30 points in 2016 and 2.34 points in 2013—compared to years without the effect, such as 2018, when the IQR reached 5.62 points. This indicates a greater concentration of observations around the median during periods of seasonal market upswings (

Figure 14).

In years exhibiting the “December Effect” effect, the distribution demonstrated a tendency toward positive skewness (e.g., 0.82 in 2013, 0.49 in 2020), indicating a higher frequency of values above the median. It is noteworthy that kurtosis was predominantly negative during these years (e.g., −1.05 in 2017, −1.02 in 2020), suggesting a distribution that is flatter than the normal distribution (

Figure 15).

Comparison of the 10th and 90th percentiles between years with and without the “December Effect” effect reveals that differences in price levels are evident across the entire distribution (

Figure 16). For instance, in 2021 (a year with a strong effect), the 10th percentile stood at 216.96 points, whereas in 2018 (a year without the effect) it was only 152.02 points. Similar disparities were observed for the 90th percentile: 226.44 points (2021) versus 162.96 points (2018).

The case of 2023 is particularly noteworthy, as despite being classified as a year exhibiting the “December Effect,” it displayed atypical characteristics: a relatively high standard deviation (4.87 points), a wide interquartile range (8.75 points), and an exceptionally low kurtosis (−1.77). This may suggest a shift in the nature of the phenomenon in recent periods.

In conclusion, the December Effect in the ESG index emerges as the most persistent yet least predictable of the studied anomalies. Its dependence on the interplay of behavioral factors (‘window dressing’, investor optimism) and structural drivers (regulation, liquidity) means that its future occurrence is contingent on a favorable alignment of these conditions. Our wavelet-based approach has successfully decomposed this complexity, moving beyond a binary ‘effect vs. no-effect’ classification to characterize the intensity and quality of the anomaly in each instance.

In the context of ESG models, the results indicate that in socially responsible indices, the “December Effect” manifests itself in a more subdued manner compared to traditional indices, characterized by lower volatility and more balanced growth. This likely reflects the nature of ESG companies, which tend to be less susceptible to speculative price movements. At the same time, the persistent seasonality in December quotations suggests that behavioural factors continue to play a significant role in shaping year-end prices, even in sustainable investments.

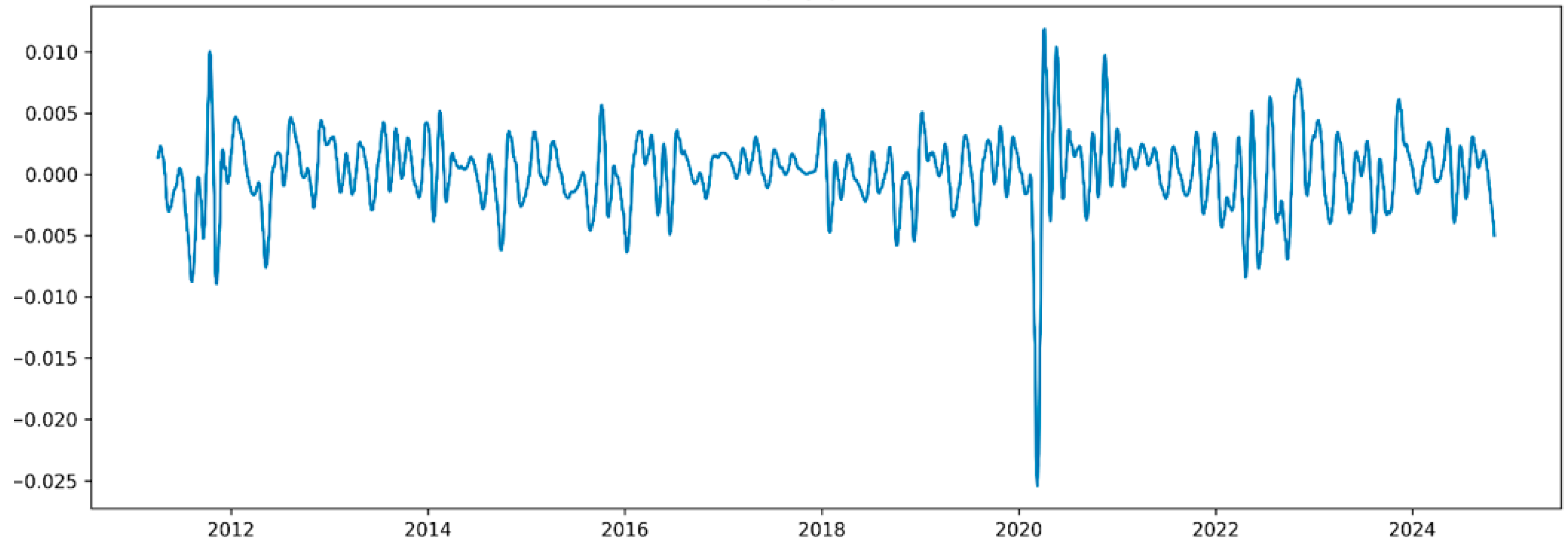

5. Extended Interpretation of Wavelet Analysis Results Through the Lens of Adaptive Market Theory

To fully demonstrate the unique value added by the applied wavelet analysis, its results were contrasted with traditional approaches, in particular the null regression model and monthly averaging. The null model for the entire time series (December 2021–November 2024) indicates an average price level of 207.74 units. For the illustrative period of October 2024, the monthly average was 218.51, with a daily standard deviation of 3.34. The fundamental weakness of this approach is its complete lack of information regarding intra-period dynamics: the price oscillated between 216.16 and 226.59, and the daily deviation from the monthly average reached 8 units. Averaging effectively masks this variability.

In this context, wavelet analysis provides a decisive insight. While traditional metrics offer a static summary, the wavelet power spectrum analyzes volatility simultaneously in the time and scale (time horizon) domains. This allows for the identification of transient, concentrated episodes of volatility (“power clusters”) that are invisible in averaged data.

Using October 2024 as an example, the raw time series shows an overall downward trend. Wavelet analysis enables testing the nature of this change. If the spectrum for this period revealed significant clusters of high power at short scales (e.g., 2–8 days), this would be evidence that the decline was driven by a series of short-term informational shocks. If, on the other hand, the power concentrated at longer scales (above 16 days), it would suggest the influence of a single, more profound factor of a more permanent nature. This distinction is crucial: traditional methods inform about the magnitude of the change, while wavelet analysis infers its structure and probable mechanism.

The direct comparison thus highlights the key advantage of the methodology. The null model for October merely indicates that the average price was elevated relative to the long-term average. Wavelet analysis, through its ability to decompose the signal, provides a hypothesis concerning the causes: whether this premium was stable or—more likely given the observed decline—was the resultant of a high opening and a subsequent correction, the dynamics of which can be examined across different horizons. This capacity to locate and characterize transient risk regimes in time and scale, entirely overlooked by averaging metrics, constitutes the fundamental value added of the presented methodology in the context of analyzing ESG markets, which are susceptible to episodic informational shocks of varying persistence.

It should be emphasized that the discussion of October 2024 serves as a conceptual illustration of the wavelet methodology’s analytical potential. The specific scale-domain patterns mentioned (e.g., potential 2–8 day clusters) are hypothetical examples used to contrast the wavelet framework with traditional approaches, rather than reported empirical findings from this specific sub-period analysis.

6. Discussion

The results of our research on the occurrence of calendar anomalies—i.e., month-of-the-year effects in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index in 2011–2024—provide important conclusions both in the context of the literature on the subject and investment practice. Month-of-the-year effects, such as the January, July and October Effects, or the so-called December Effect, are well-described and frequently studied examples of calendar anomalies in the capital market, e.g., [

16,

18,

30]. Our analysis expands on the existing literature by exploring the sustainable investment market, which has not been sufficiently researched to date. A discussion and comparison of our results with the findings of other authors indicates that the nature and frequency of seasonal effects in ESG indices differ significantly from traditional stock market benchmarks, both in terms of regularity and macroeconomic conditions. For example, studies by [

16,

18,

67] point to the prevalence and relative persistence of the January Effect in capital markets. Our findings contradict these results, but at the same time confirm the observations of [

30,

43] that the strength of the January Effect decreases over time. These findings are strongly supported by recent research. Enow [

68] analysing major international indices (Nikkei 225, JSE, CAC 40, DAX, NASDAQ) between 2019 and 2024, found no statistically significant differences in rates of return in January compared to other months, concluding that this effect ‘is no longer visible in financial markets’ [

68]. Similarly, Jannah and Hidayat (2024) [

69] found no significant impact of the January effect on the Indonesian LQ45 index between 2020 and 2023, noting that returns in January were actually lower than in other months. Our research indicates a lack of regularity in the occurrence of the January Effect in the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index, which may be related to the occurrence of this effect in conjunction with specific market events. Furthermore, our results indicate that in the ESG asset segment, the classic interpretation of the January Effect as a tax phenomenon [

23] may not fully explain the observed relationships, implying the significant role of additional factors. This is confirmed by [

70] who points out that although the tax-driven selling hypothesis largely explains the January effect in markets with capital gains tax, in markets free of such tax (e.g., Hong Kong, Singapore), other factors are responsible for the existence of the anomaly, including investor sentiment and institutional behavior [

70]. In the context of our research, key factors included increased capital inflows into ESG funds and the growing implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

In the context of this study, it is worth noting that although global literature on the subject provides evidence for the existence of July Effects, their occurrence shows significant heterogeneity depending on the market and the research period. Studies by [

34,

35] confirm the existence of this effect in some Asian markets, while [

28] found it to be present only in selected African markets. The results of our study also reveal the presence of the July Effect in the ESG market in 2012, 2013, 2016–2018 and 2021–2024. In turn, ref. [

36] observed less volatility of the July Effect over time in Baltic countries compared to other calendar anomalies, which is confirmed by our results for the ESG index in recent years. Our results confirm the irregularity of this effect, but in the case of the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index, there is a noticeable intensification of the July Effect in 2021–2024. This may be due to the growing popularity of sustainable investments and seasonal institutional capital flows, which may be particularly concentrated on ESG assets during the summer. This observation suggests that in the case of socially responsible indices, the July Effect may take a specific form, distinguishing it from the patterns observed in traditional capital markets.

In the case of the October Effect, the results in the source literature are ambiguous. For example, ref. [

21] points to its presence in some markets, while [

30] demonstrated the lack of statistical significance of this effect in developed markets. These latter findings are strongly supported by recent research. Couto et al. (2021) [

22] analyzing nine indices from four continents, found no evidence of an October effect for the indices studied as a whole [

22]. Furthermore, Valadkhani and O’Mahony (2024), examining sector anomalies in the US market, found that none of the ten ETFs analyzed (including the S&P500) showed a significant calendar anomaly in October during the period 1999–2023 [

71]. Our study confirms these conclusions as the effect appeared episodically, mainly during periods of increased uncertainty (declining oil prices, the escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19, and fears of recession). At the same time, unlike traditional indices, the ESG index showed significantly lower susceptibility to downturns during periods when the October Effect occurred. This result is consistent with the concept of the fundamental advantage of companies with high ESG ratings [

51] and is consistent with the observations of [

61] who indicated that the October Effect is particularly noticeable in periods of instability.

The December Effect, which can be linked to investor optimism at the end of the year, is one of the most recognisable seasonal anomalies. In our study, this effect appeared frequently, but not in every period, which distinguishes it from the complete regularity described by [

40]. These results are partially confirmed by recent sectoral studies. Dinesh and D’souza (2025) [

72], analyzing Indian sectoral indices during the COVID-19 pandemic, identified a significant December effect in seven of the nine sectors studied (including IT, FMCG, manufacturing), while the telecommunications sector showed no significant differences in rates of return [

72]. A possible explanation includes factors specific to ESG investments, such as regulatory changes (e.g., the entry into force of the SFDR in 2021) or the implementation of window dressing strategies by investment funds, as pointed out by [

29].

The adaptive market hypothesis (AMH) assumes that market efficiency and the occurrence of anomalies, such as calendar effects, change over time in response to market conditions and investor behavior. The adaptive market hypothesis (AMH), developed by [

73], is one of the latest models describing the operation of financial markets. AMH is an extension of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). AMH does not negate the efficient market hypothesis but merely extends it. The basic assumptions of AMH are as follows: entities act selfishly (they strive for profits), make mistakes, and learn and adapt; competition drives adaptation and innovation processes; natural selection shapes the market environment; and evolution determines market development. The main relationships arising from the adaptive market hypothesis are:

Market efficiency depends on a combination of environmental conditions and the number of so-called species (each group of participants is a single species; one species may be investment funds, another may be individual investors, etc.);

Preference variability—a given investor’s preferences will change depending on their situation;

There is a relationship between risk and return, but it is not stable—the relationship between return and risk depends on investor preferences as well as the environment in which they operate (e.g., legal, regulatory, tax environment);

Arbitrage opportunities exist, but their emergence and disappearance is cyclical;

Investment strategies are effective or ineffective depending on market conditions;

Innovation is the key to survival [

74].

Unlike the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), the AMH allows for the periodic appearance and disappearance of anomalies. Furthermore, it assumes that investors respond to information rationally, and that calendar anomalies (e.g., the January effect) are recurring patterns that indicate market inefficiency (because these patterns should be arbitrageable). Research indicates that calendar anomalies are time-varying and dependent on market conditions, which supports the adaptive market hypothesis. The AMH better explains the appearance and disappearance of anomalies than the classical efficient market hypothesis, both in developed and emerging markets. Ref. [

75] show that calendar anomalies support the AMH, with the behavior of each calendar anomaly varying over time. They also conclude that some calendar anomalies occur only under specific market conditions and suggest that the AMH offers a better explanation of the behavior of calendar anomalies than the efficient market hypothesis. Ref. [

36] confirmed that Baltic stock markets exhibited AMH-supporting behavior. They found that the possibility of achieving abnormal returns from investment strategies based on month-of-year effects (January and July) disappeared during the 2007–2009 financial crisis.

Ref. [

76] demonstrate that the adaptive market hypothesis (AMH) explains calendar anomalies in 16 major stock indices across 10 markets. Empirical results show that calendar anomalies in the studied groups exhibit time-varying behavior, evolving through patterns that shift markets between periods of efficiency and inefficiency, confirming the validity of the AMH model. The results also highlight that calendar anomalies reappeared after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in international markets. Ref. [

77] finds that African markets proved inefficient due to the presence of calendar anomalies. The results of this study support the adaptive market hypothesis, which posits that constantly changing stock markets give rise to new calendar anomalies.

Comparing the results of our study with prior literature, it can be concluded that in the case of ESG indices, month-of-the-year effects are less predictable and more dependent on the macroeconomic, social and regulatory context. These results challenge the view that calendar effects are permanent and universal in nature. As regards ESG indices, their occurrence appears to be conditional, which confirms the thesis of adaptive market efficiency and points to the need for seasonal strategies to be modified to include additional fundamental factors.

7. Conclusions

Analysis of month-of-the-year effects for the STOXX Global ESG Social Leaders Index in 2011–2024 using a wavelet transform identified the four calendar anomalies that are most frequently described in the literature: the January Effect, the July Effect, the October Effect and the so-called December Effect. The results confirmed their occurrence, but in an irregular manner and with varying intensity. For example, over a period of 14 years, the January Effect appeared six times (in 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2023), which indicates a lack of regularity. The occurrence of this effect in the studied index can be linked to both classic market factors and capital inflows into ESG funds in specific years. The July Effect has shown greater stability in recent years, which may suggest the growing importance of seasonality in capital flows in the ESG segment. The October Effect was episodic and occurred mainly in periods of increased macroeconomic uncertainty, with the scale of declines being smaller than in traditional benchmarks. The December Effect occurred in most of the years analysed, but its absence in some periods of pronounced market upswings indicates that in the case of ESG indices, regulatory and structural factors may modify classic seasonal patterns.

The results of this study indicate that the anomalies observed in the ESG asset segment are different in nature than those in capital market indices. They are characterised by less regularity and stronger dependence on external factors, such as regulatory changes, global economic events and investor preferences. From an investment practice perspective, the results suggest that strategies based solely on classic month effects may be less effective for ESG indices, with additional filters being required, including analysis of macroeconomic, regulatory and structural factors. More broadly, the results confirm the need for further research on seasonality in the sustainable investment segment, taking into account its specific characteristics and the dynamically changing market environment.

This study makes a significant contribution to the financial literature by empirically confirming the existence of calendar effects in ESG indices and identifying specific seasonal patterns that are characteristic of sustainable capital markets. The innovative application of wavelet analysis to study seasonality in sustainable markets enabled the development of a procedure for identifying calendar effects in non-stationary time series, as well as the integration of quantitative methods with the analysis of macroeconomic and regulatory factors. The study also enriches existing knowledge about the efficiency of ESG markets, providing new evidence on their degree of efficiency and quantifying the impact of behavioural factors on the pricing of ESG assets. Furthermore, it contributes to a deeper understanding of market mechanisms in ESG investments. The results provide both theoretical and practical guidance for diverse stakeholder groups: they enable investors and financial analysts to use the identified calendar effects in the process of constructing investment portfolios, as well as to strengthen forecasting tools by taking into account the specific seasonality of ESG markets. In addition, the identified patterns can be an important element in hedging strategies that consider the seasonality of ESG markets. For regulators and supervisory authorities, they enable the identification of potential areas of increased volatility that require supervisory attention, and the design of regulations that support the efficiency of the ESG market. For researchers and the academic community, the results of the study also set new research directions, pointing to the need for further analysis of anomaly dynamics in various segments of the ESG market, identifying methodological gaps in the analysis of sustainable financial instruments, and proposing the integration of the sustainable development perspective into behavioural finance theory. The results represent a significant contribution to the development of research on sustainable market efficiency theory, time series analysis methodology in finance, and practical aspects of ESG portfolio management. The results also expand the boundaries of contemporary economic knowledge in a way that is relevant to both financial theory and practice.

A significant methodological contribution to the study of calendar anomalies is the use of a wavelet transform, which made it possible to capture local and short-term patterns that are not accessible using traditional methods. However, the main limitation of our study is its focus on analysis of a single ESG index. This approach limits the possibility of generalising the results to other market segments, and the results cannot be directly extrapolated to regional or industry indices, or to portfolios with different methodological structures. For this reason, we plan to expand the analysis in the future to include a comparison of several global and regional ESG indices, as well as a comparison with traditional benchmarks. Another important direction for exploring the ESG market identified by our study is analysis of the impact of specific regulatory and macroeconomic events on the intensity of individual calendar effects in the ESG market.