1. Introduction

Rainfall-runoff prediction has always been one of the core topics in hydrology [

1]. Against the backdrop of global climate change leading to increased frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events, hourly-level rainfall–runoff prediction is particularly crucial for supporting rapid decision-making and effective disaster prevention [

2]. Hourly-level prediction can capture the instantaneous dynamics of rainfall peaks and runoff responses, which is essential for real-time response measures including urban flood control, flash flood warning, reservoir operation, and population evacuation. The rainfall–runoff process is influenced by multiple factors including meteorological conditions, watershed topography, and soil characteristics, exhibiting high nonlinearity and spatiotemporal variability [

3]. These characteristics pose challenges for traditional conceptual and process-based hydrological models, particularly for hourly-scale prediction. In practice, achieving satisfactory performance often requires nontrivial parameterization and extensive calibration, and the computational burden can become substantial when repeated model evaluations are needed for calibration and sensitivity/uncertainty analyses in large-sample settings. Moreover, model structural simplifications and parameter uncertainty may limit performance for fast hydrological responses at sub-daily scales, motivating data-driven alternatives [

4].

To overcome the limitations of traditional models, data-driven methods have gradually become a research hotspot in rainfall–runoff prediction [

5,

6]. Compared with traditional methods, data-driven approaches can provide higher prediction accuracy and generalization ability by mining complex spatiotemporal patterns in historical data. With the accumulation of high-resolution meteorological and watershed data, machine learning technologies, especially deep learning methods, have made significant progress in rainfall–runoff prediction [

7], offering new possibilities for hourly-level prediction.

Although deep learning continuously improves prediction accuracy through optimizing model architectures, its black-box nature remains a significant challenge in the field of disaster prevention. Low interpretability models may undermine decision-makers’ trust, thereby affecting the quality and efficiency of disaster prevention decisions [

8]. Therefore, enhancing model interpretability while ensuring prediction accuracy has become a research frontier in the hydrology field [

9,

10]. Researchers typically address this issue through two approaches: introducing physical constraints and incorporating relevant variables into model calculations. In terms of introducing physical constraints, ref. [

11] modified the LSTM architecture using left stochastic matrices to redistribute water among memory units, ensuring water conservation and thus performing excellently in high-flow prediction. Ref. [

12] combined reservoir physical mechanism encoding with differentiable modeling strategies to integrate prior physical knowledge into deep learning models, achieving accurate prediction of reservoir operations. Some studies incorporate physical constraints into the loss function of neural networks to implement interpretable physical information in graph neural network flood forecasting models [

13]. By adding relevant variables, researchers introduce guiding processes into models based on hydrological physical mechanisms. For example, ref. [

14] proposed an entity-aware long short-term memory network for regional hydrological simulation, which significantly outperformed traditional models by directly learning similarities between meteorological data and static watershed attributes, and surpassed region-specific and watershed-specific calibration models in both performance and interpretability. Furthermore, ref. [

15,

16] significantly improved the simulation accuracy of rainfall-induced flood inundation processes by incorporating topographic data. For catchment-scale rainfall–runoff sequence modeling, topographic information is typically provided as static watershed attributes rather than being explicitly modeled.

In the field of deep learning, Transformer architecture has demonstrated excellent performance in natural language processing, computer vision, and other domains due to its powerful self-attention mechanism [

17,

18]. Its unique design enables efficient processing of complex patterns in sequential data, making it particularly suitable for high-dimensional spatiotemporal data in rainfall-runoff prediction. Refs. [

19,

20] pointed out that Transformer-based prediction models are more capable of handling long-term sequence prediction tasks compared to LSTM, as their self-attention mechanism can effectively capture long-distance dependencies. However, some research has indicated [

21] that the basic Transformer shows insufficient recognition of long-term memory effects in the time dimension on benchmark datasets such as the CAMELS runoff dataset, requiring further improvements to adapt to the complex dynamics of hydrological systems. The Transformer-based model proposed by [

22] significantly outperformed LSTM-based sequence-to-sequence models in 7-day-ahead runoff prediction and demonstrated that its parallel computing capability is more suitable for processing large-scale datasets. Subsequently, a pyramid Transformer rainfall–runoff model was proposed [

23], which achieves accurate modeling of regional rainfall runoff by integrating information from different temporal resolutions. Compared to daily runoff prediction tasks, hourly-level prediction involves 24 times more data volume, with more drastic numerical changes, significantly increasing the demand for efficient computation and long-term sequence modeling capabilities [

24], while also requiring the model to be more robust. Currently, research on using water balance constraints for deep learning models has mostly focused on daily-scale data, and there are no existing improvements with physical constraints for Transformer-based models.

Reliable hourly rainfall–runoff prediction is essential for sustainable water resources management, including flood early warning, resilient infrastructure operation, drought preparedness, and ecological flow protection. In many regions, decision-making is constrained by limited monitoring capacity and the prevalence of ungauged or poorly gauged basins, which introduces substantial uncertainty in risk assessment and water allocation. Improving predictive skill while maintaining physically plausible behavior therefore contributes to sustainability goals by supporting timely and robust hydrological decision-making under data scarcity and hydro-climatic variability.

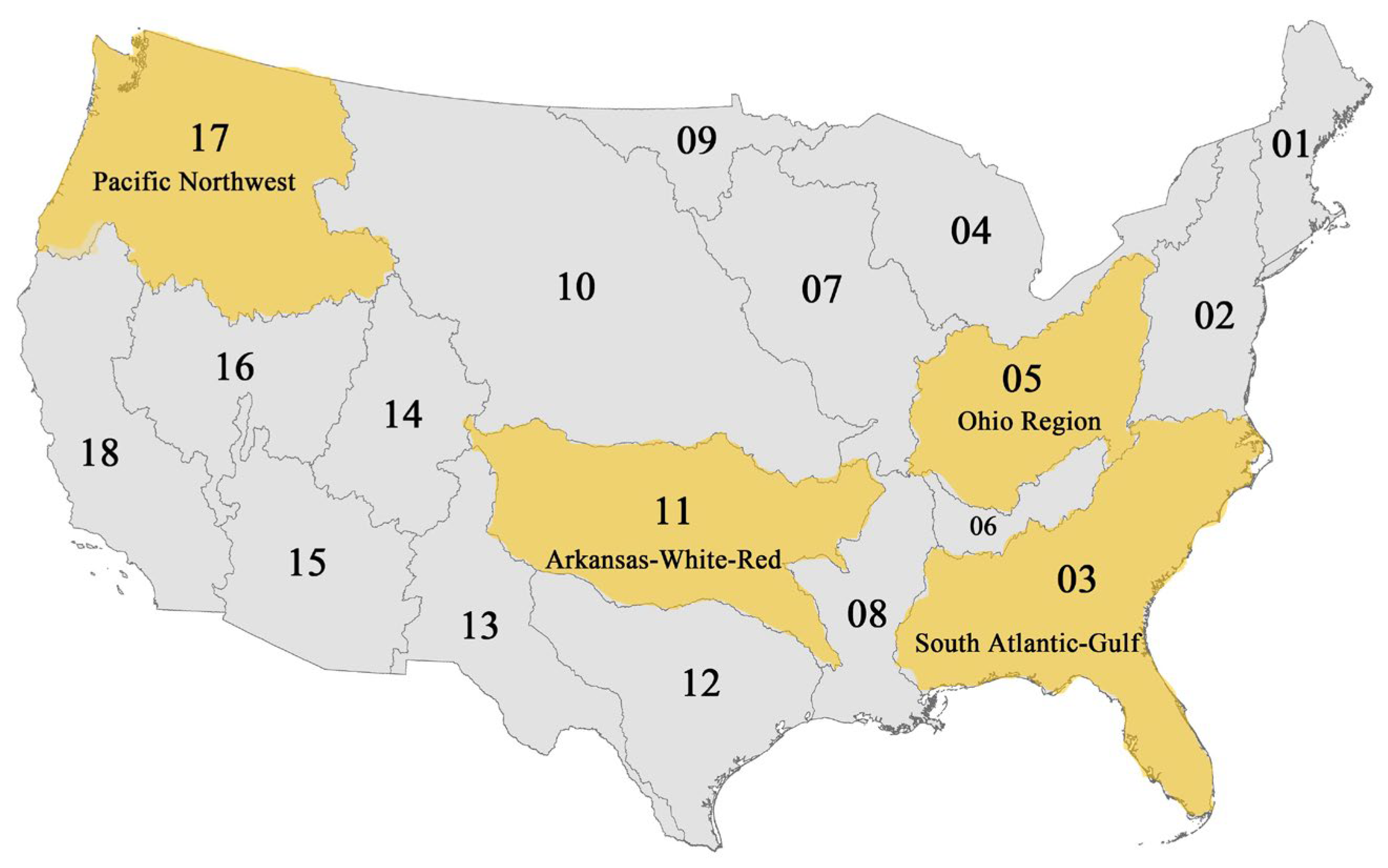

Based on the above challenges and opportunities, this study adopts an hourly-level dataset from hundreds of watersheds in the United States and proposes a novel Transformer regional rainfall–runoff model. The model enhances the accuracy and reliability of hourly-level regional rainfall–runoff prediction by incorporating water balance constraints. Additionally, we evaluate the model’s performance across different types of catchment areas.

The contributions of this research are mainly reflected in two aspects. First, we propose a Transformer model for regional runoff prediction that transforms time-domain data into frequency domain for computation and controls the model output to maintain physical rationality through a water balance encoder. Second, we apply the model to an hourly Rainfall–Runoff dataset, demonstrating its advantages compared to baseline models. The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a detailed introduction to the proposed method and model design;

Section 3 explains the experimental design and datasets;

Section 4 presents experimental results and analysis;

Section 5 summarizes the research contributions and outlines future directions.

2. Methods

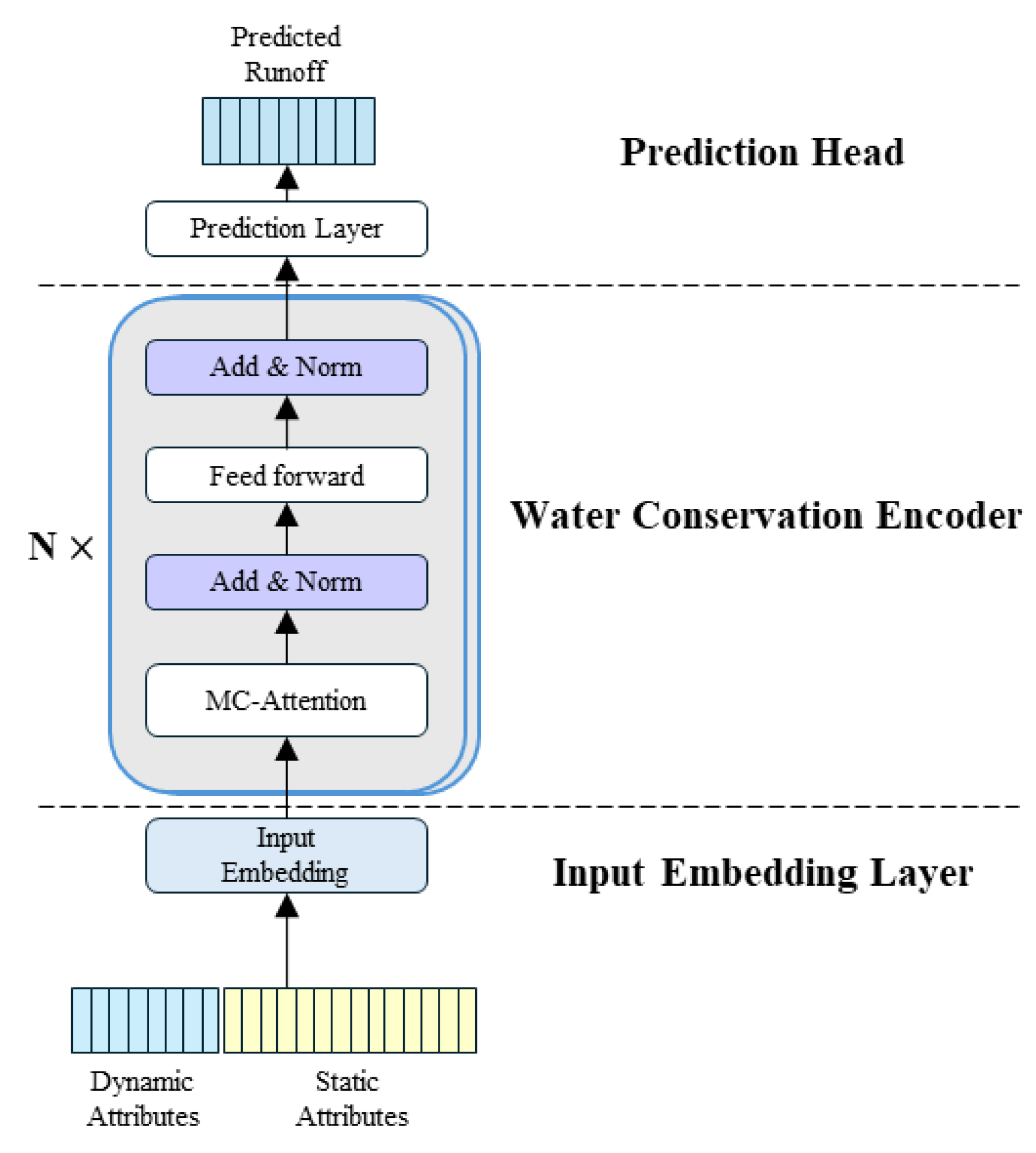

We propose a Transformer-based regional rainfall–runoff model, named MC-former, whose architecture consists of an input embedding layer, a physics-constrained Transformer encoder, and a regression prediction head, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The functions of each component are introduced in the following subsections.

2.1. Input Embedding Layer

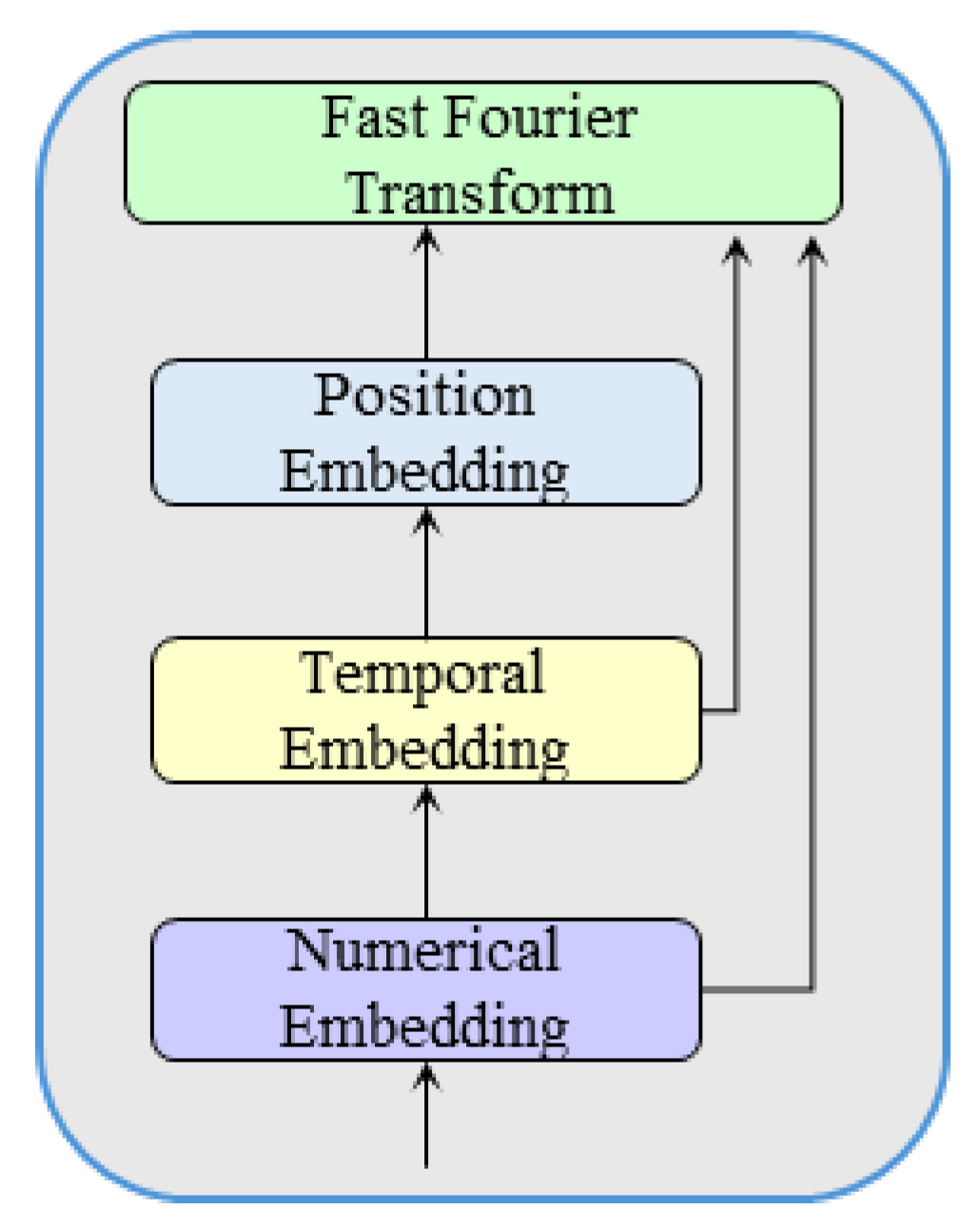

The input embedding layer generates a comprehensive embedding representation for time series data, combining original numerical features, temporal features, and positional information. The input embedding layer structure is shown in

Figure 2. When using Transformer architecture models for regional rainfall–runoff modeling, watershed static attributes can effectively distinguish different target watersheds [

25], reducing the possibility of catastrophic forgetting in the model. In this context, ref. [

14] pointed out that directly concatenating watershed static attributes with dynamic meteorological data is more efficient than independently computing watershed static attributes. Therefore, watershed static attributes are concatenated with dynamic meteorological variables to form the input sequence of the model. Different types of input features are normalized separately using min–max scaling to eliminate scale differences and improve training stability.

First, the input sequence undergoes linear transformation, mapping each input feature to a high-dimensional space to obtain numerical embeddings. After that, temporal information is mapped to the embedding space. Most time series forecasting models based on Transformer architecture require hierarchical global timestamp information to encode seasonal and long-term ordinal information [

26,

27] to obtain temporal embeddings. Finally, positional embeddings are used to generate a position vector for each time step’s input position. We adopt the most commonly used sine and cosine functions in Transformer-like models for positional embedding, with the specific formula as follows:

The three embeddings are added to combine numerical, temporal, and positional features. Zhou [

28] pointed out that frequency domain representation can effectively capture and model frequency features in time series, thereby improving model performance, especially when processing time series data with obvious periodicity or frequency patterns. Since rainfall–runoff data typically exhibits significant seasonal or periodic variations, we apply fast Fourier transform to the combined input embedding (which integrates numerical, temporal, and positional information), converting the time domain data into frequency domain data for computation in the encoder layer, and enriching long-range temporal dependencies, as expressed in Equation (3):

where

denotes the 1D FFT applied along the time dimension, and the encoder then takes

as its input. Here, the Fourier transform is employed as a representation-level transformation to expose periodic and long-range temporal patterns to the attention mechanism, rather than as a strict physical spectral analysis of the hydrological signal.

2.2. Physics-Constrained Transformer Encoder

The model we propose is based on the Transformer model, whose encoder consists of multiple encoder layers, each composed of an attention layer and a feed-forward network layer. The core component of the attention layer is the attention mechanism. The attention mechanism calculates the similarity between query vectors (Query) and key vectors (Key) and uses this as weights to perform a weighted sum of value vectors (Value), thereby enabling the model to dynamically aggregate different positions in the input sequence. The process can be described as follows:

where

is the query vector,

is the key vector,

is the value vector, and the function

f transforms the result into an output. This output can then be used for further computations in the neural network.

Depending on the method of calculating similarity, there are also many variants of the attention mechanism, among which the original Transformer adopts the most common scaled dot-product attention. The correlation between each query vector and key vector is described by the attention weight matrix, and the attention weight calculation formula is as follows:

where

is the dimension of the key.

The output of the scaled dot-product attention can be simplified as follows:

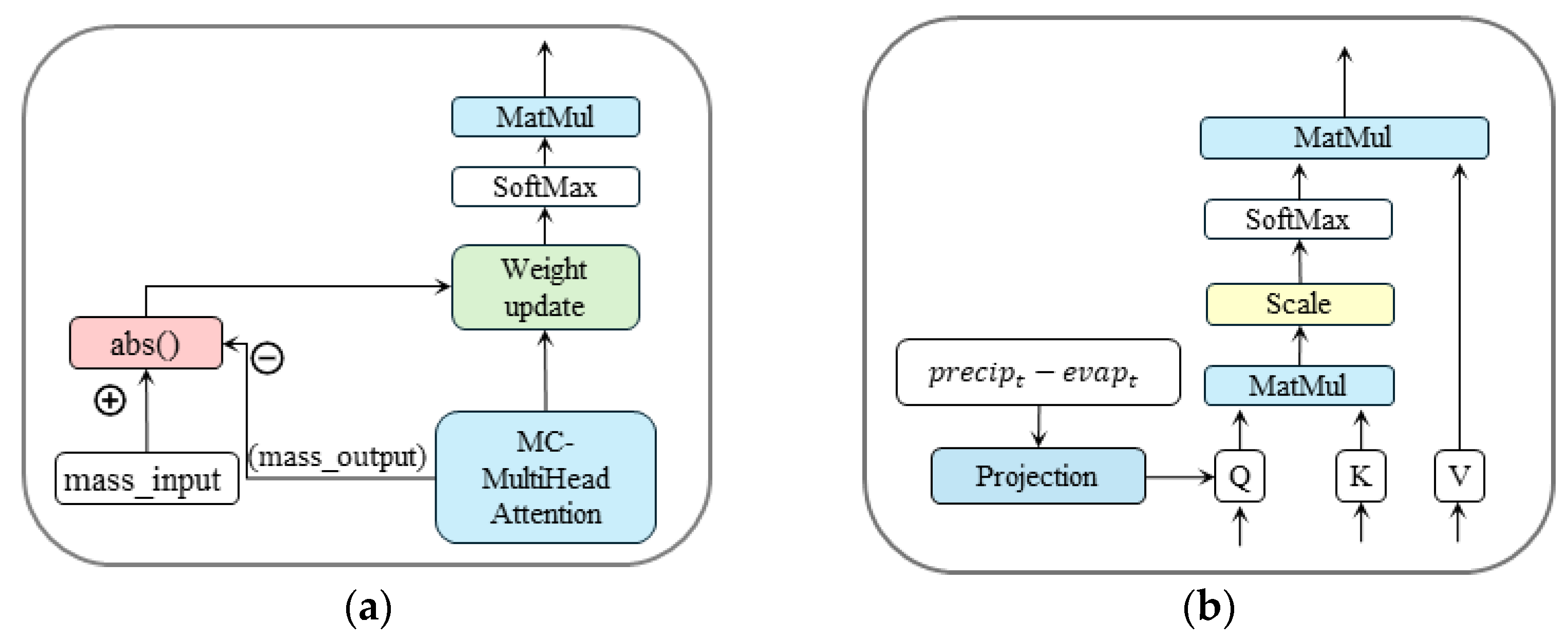

We define MC-attention (mass conserving attention) as a modified self-attention mechanism in which cumulative water input and a layer-wise mass-tracking state are explicitly tracked, and their discrepancy is used to bias attention weights toward physically consistent aggregation.

Compared with standard scaled dot-product attention, MC-attention introduces two key modifications: (1) re-engineering the forward propagation of the multi-head attention module to maintain the layer-wise mass-tracking state, and (2) integrating cumulative water-input signals into the attention computation. The overall structure is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Following a simplified conceptual view of the surface water balance, precipitation and evapotranspiration are used to construct a cumulative input water signal that serves as a guiding constraint rather than an explicit discharge equation. Specifically, the cumulative input water volume from the beginning of the input sequence to time step i is defined as follows:

where

denotes the rainfall amount at time

, and

denotes the potential evapotranspiration at time

. This cumulative net-input term is used as a guiding constraint signal rather than an explicit runoff generation equation. Storage-related processes such as initial basin storage, groundwater delay, and subsurface routing are not explicitly represented in Equation (6). This does not imply zero initial storage; rather, storage dynamics are not explicitly parameterized here and are expected to be learned implicitly from long input sequences and catchment attributes.

We enhance the calculation method of query vectors in the attention layer by projecting the input quality term onto each query, allowing the model to learn and preserve the patterns of water quantity transformation. Meanwhile, to continuously track the amount of water discharged by the model during the self-attention calculation at each layer, we maintain a cumulative water amount from the previous layer output for each query position.

If the encoder has a total of k layers,

we set

. Following the practice in MC-LSTM, we designate the 0th output channel of each encoder layer as discharge. This choice is empirically justified through a sensitivity analysis (

Appendix A.1), which shows that the model is not overly sensitive to channel selection, while channel 0 provides the most stable and robust performance across basins. Then, the accumulated water volume from the previous layer output at the

-th time step can be described as follows:

where

denotes the 0th output channel of the

-th encoder layer at time step

. This quantity represents a layer-wise mass-tracking state rather than a physical time integration; it is used to monitor the cumulative discharge generated across encoder layers.

For Transformer architecture, due to the lack of recurrent structures, relying solely on water quantity input to guide attention to achieve water conservation is not realistic. We need to guide the attention layer output toward consistent water-conservation behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to calculate the difference between the input water quantity and the output water quantity of each encoder layer to obtain the water quantity difference penalty term to bias the attention computation in the

-th layer:

where

is the input cumulative water amount, and

is the output cumulative water amount from the previous layer. In implementation,

is computed for each query time step i and then broadcast along the key dimension to form a penalty matrix compatible with the L × L attention-weight matrix. For each encoder layer, the cumulative output water mass is tracked in a layer-wise manner. Before computing attention in the

-th layer, the model uses the mass-tracking state

accumulated up to the immediately preceding layer

at each time step

. After the attention output of layer

is obtained, this mass-tracking state is updated and passed to the next layer, enabling progressive enforcement of mass conservation across the depth of the network. The resulting water-mass discrepancy is incorporated into the attention weight computation of the current layer, guiding the attention mechanism toward physically consistent runoff generation.

After obtaining the water-mass difference penalty term, we can adjust the weights of the water conservation attention in each encoder layer by taking the logarithm of the standard attention weight matrix W and subtracting the penalty term:

where

is the coefficient regulating the conservation strength, and

is a small value to prevent the log calculation from becoming zero. Here,

∈

is the row-wise softmax-normalized attention-weight matrix.

When

, it makes the attention bias toward the group of keys that are better for water conservation. Afterwards, we renormalize

by applying a row-wise softmax over the key dimension, and use the resulting normalized weights to combine V, obtaining the conservation-guided attention output:

After the attention layer output undergoes residual connection and layer normalization, it enters the feed-forward network layer. After performing linear transformation and nonlinear activation function calculations on the input, residual connection and layer normalization operations are performed again, and the output result is sent to the prediction head.

2.3. Prediction Head

In time series forecasting tasks, encoder-only architectures demonstrate excellent performance in many scenarios, especially when efficiently processing long sequence data [

29]. First, we use inverse Fourier transform to convert the runoff frequency domain predictions from the encoder output into time domain predictions. Then, we use a linear layer as the prediction head to generate the time-domain-predicted runoff sequence. It should be noted that the inverse Fourier transform in MC-former is not intended to reconstruct a physically interpretable time-domain signal from a strictly linear spectral representation. The inverse FFT is used as a representation-level mapping to project learned frequency-aware features back to the time domain for prediction, rather than as a strict inverse spectral operator. Multi-step forecasts are generated autoregressively (rolling), i.e., the model produces one-step-ahead predictions iteratively until the full forecast horizon is obtained.

2.4. Metrics and Benchmark

For performance evaluation, we adopt the following metrics: Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), Pearson correlation coefficient (r), Kling–Gupta efficiency (KGE), and mean squared error (MSE).

NSE is a metric that measures the degree of agreement between the hydrological model’s predictions and observed data. Its value ranges from negative infinity to 1, with a value closer to 1 indicating better model fit. The formula for calculating NSE is as follows:

where

is the observed runoff at time step

,

is the predicted runoff at time step

,

is the number of time steps, and

is the mean of the observed runoff.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is commonly used to evaluate the linear relationship and correlation between hydrological model predictions and measured data. The closer the value is to 1, the stronger the linear relationship between the model predictions and measured values, indicating good model performance. The calculation formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient is as follows:

where

is the covariance between simulated and observed data;

,

are the standard deviations of simulated and observed data.

KGE comprehensively evaluates model performance by integrating multiple metrics. Its value ranges between negative infinity and 1, with the KGE value closer to 1 indicating a better fit of the model to the data. The calculation formula for KGE is as follows:

MSE is a commonly used loss function in regression tasks, used to measure the mean squared error between model predictions and actual values. Its formula is as follows:

In addition to NSE, KGE, Pearson correlation, and MSE, three flow regime-specific metrics are used to further diagnose model performance under different runoff conditions: high flow bias (FHV), medium flow bias (FMS), and low flow bias (FLV). These metrics quantify relative bias under high-, medium-, and low-flow conditions, respectively, and complement NSE and KGE by explicitly assessing flood peaks, normal flow stability, and low-flow behavior. These metrics are defined mathematically as follows:

are defined based on quantiles of the observed discharge . Specifically, denotes the set of time indices corresponding to high-flow conditions, defined as the top 2% of observed flows. represents medium-flow conditions, defined as observations between the 20% and 70%. corresponds to low-flow conditions, defined as the bottom 30% of observed flows. These percentile-based definitions ensure that the flow regimes are determined in a basin-specific and scale-invariant manner.

We will use the Transformer model [

25] and the LSTM model [

24] as baseline models to compare with our proposed model. All baseline models were reimplemented/retrained under the same experimental setup and data splits as MC-former (training/validation/test), rather than using published performance values. Both baseline models also use static watershed variables for computation; in other words, the baseline models also have regional runoff prediction capabilities. The hyperparameter values for the baseline models follow the specifications in their respective papers, while other training settings (e.g., input window, optimizer, and early-stopping criterion) are kept consistent across models whenever applicable to ensure a fair comparison.

5. Conclusions

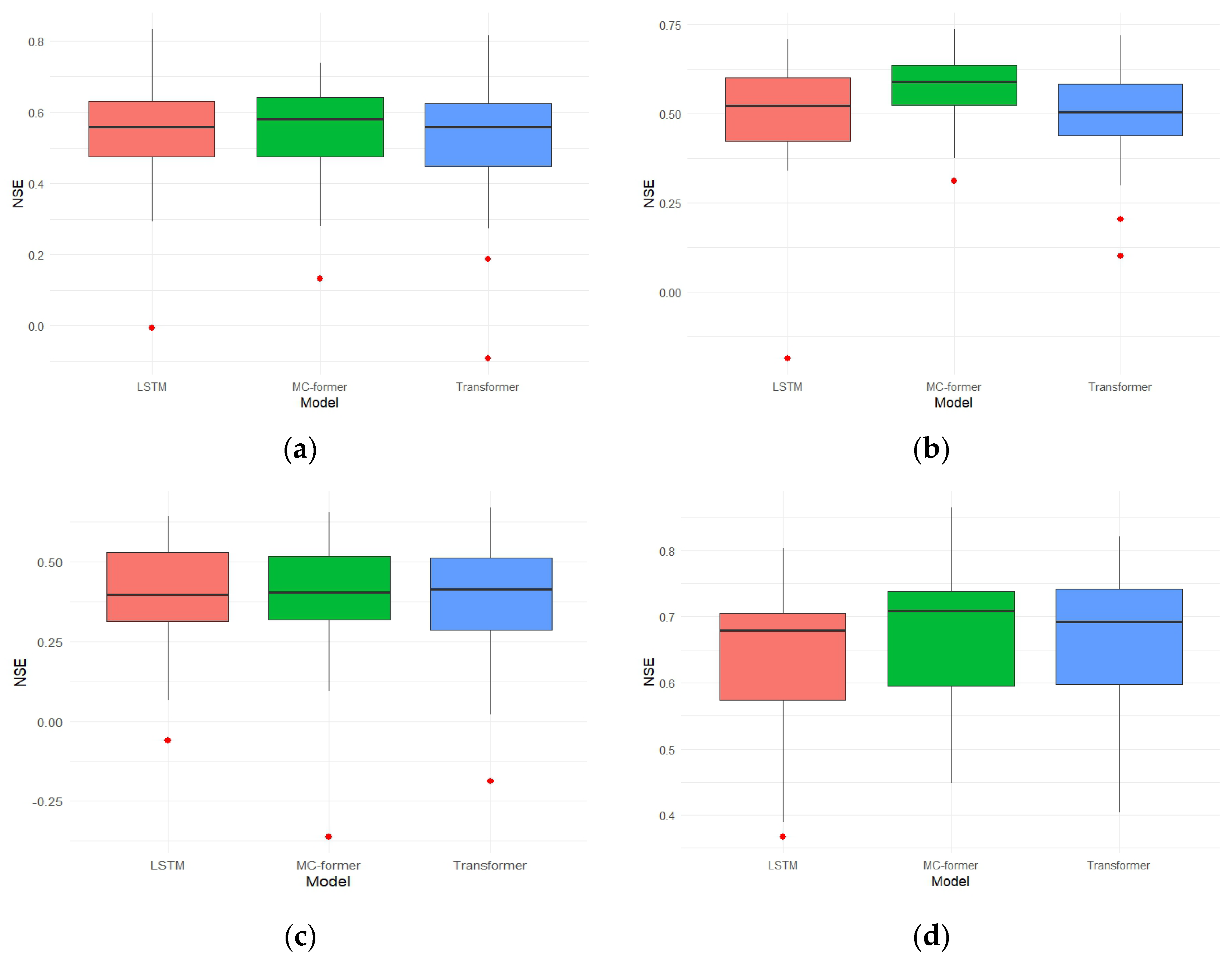

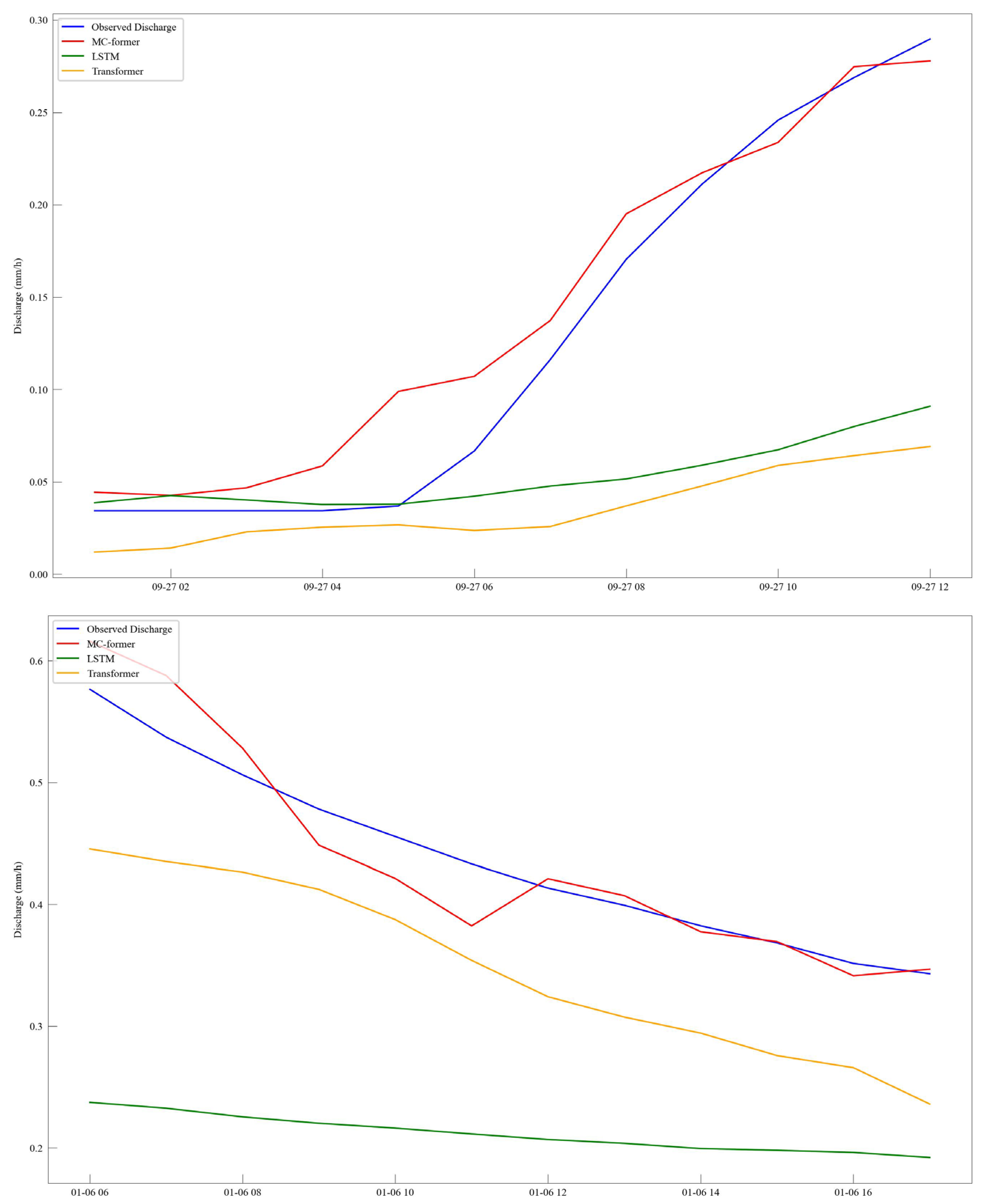

This study developed MC-former, a physics-constrained Transformer framework for hourly regional rainfall–runoff prediction, in which attention aggregation is guided by water-balance-based constraints. Extensive experiments across 471 basins indicate that the proposed physics-guided attention mechanism yields robust performance gains over baseline models, while enhancing physics-guided interpretability in data-driven hydrological modelling.

Beyond overall accuracy gains, the results provide two key insights for regional and ungauged basin prediction. First, training with hydro-climatically and physiographically similar regions substantially improves general predictive skill, indicating that attribute-based similarity offers a principled basis for regional knowledge transfer. Second, incorporating complementary dissimilar-region data can help mitigate bias in peak-flow simulation, suggesting a trade-off between overall accuracy and extreme-event representation.

Despite these advantages, the proposed framework may face limitations under extreme flash-flood conditions and in snow-dominated basins, where additional physical processes are not explicitly represented. From a sustainability perspective, the combination of physics-guided attention and similarity-aware regional training provides a practical pathway for improving hydrological forecasting in data-scarce regions. Future work will focus on uncertainty quantification and further interpretability analysis to support more robust and decision-relevant water resources management.