A Comprehensive Review of Human-Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Systems: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Human–Robot Collaborative Task Allocation

2.1. Deep Learning-Based Human–Robot Collaborative Task Allocation

2.2. Large Language Model-Based Human–Agent Collaborative Task Allocation Methods

3. Concept, Significance, and Development of Multimodal Perception

3.1. Multimodal Perception Based on Deep Learning Architectures

3.2. Multimodal Perception Based on Pre-Trained Large Models

4. The Concept and Core Value of Human–Robot Hybrid Augmented Interaction

4.1. Traditional Hybrid Augmented Interaction Methods Based on AR/VR/MR

4.2. Hybrid Enhanced Interaction Method Based on Visual Language Model

5. Basic Concepts of Human–Robot Fusion Enabled by Digital Twin

5.1. Environmental Perception and Scene Modeling

5.2. Human State Perception and Modeling

5.3. System Organization and Collaborative Logic for Complex Collaborative Scenarios

6. Adaptive Motion Control

6.1. Concept of Adaptive Motion Control

6.2. Adaptive Motion Control Based on Path Planning

6.3. Adaptive Motion Control Based on Collision Detection

6.4. Adaptive Motion Control Based on Code Generation

7. Human–Robot Collaborative Decision-Making

7.1. Human–Robot Collaborative Decision-Making Based on Large Language Models

7.2. Human–AI Collaborative Decision-Making Based on Reinforcement Learning

8. Applications of Human–Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Technologies

9. Conclusions and Future Work

9.1. Summary

9.2. Outlook

- Develop dynamic task allocation algorithms fused with real-time multi-source data (personnel fatigue status, equipment health indicators, task priority) and LLM-based intent understanding, enabling self-optimization of human–robot division of labor in complex production environments;

- Improve the environmental robustness and few-shot learning capabilities of multi-modal perception through cross-modal fusion (vision, audio, tactile, physiological signals) and pre-trained model fine-tuning, empowering robots to proactively perceive human operation intentions and adjust collaborative strategies in real time.

- Promote the development of lightweight collaborative robots with high flexibility and low load, and optimize hardware integration of multi-modal sensors (e.g., miniaturized vision cameras, wearable physiological monitors);

- Construct a modular software framework based on microservices, realizing plug-and-play of core functional modules (perception, interaction, control, decision-making) and supporting rapid adaptation to diverse production scenarios (e.g., aerospace component assembly, electronic product customization) through digital twin-driven module configuration.

- Build a multi-level safety protection system integrating active collision avoidance (based on real-time trajectory prediction), human physiological state monitoring (e.g., EEG-based fatigue detection, eye-tracking attention recognition), and rapid emergency stop mechanisms, ensuring human safety in close-range human–robot collaboration;

- Formulate industry-wide ethical norms and data security standards, including privacy protection of human operation data (e.g., desensitization of physiological signals and operation behavior), accountability definition for collaborative decision-making (distinguishing human/robot responsibilities in accident scenarios), and AI ethics review mechanisms for autonomous decision-making modules.

- Promote the formulation of international standards for HRC system interfaces (e.g., robot-sensor communication protocols), data formats (e.g., multi-modal data exchange specifications), and performance evaluation (e.g., collaborative efficiency, safety indicators), realizing interoperability between different brands of robots, perception devices, and digital twin platforms;

- Build an industrial ecosystem integrating technology research (universities and research institutes), product development (equipment manufacturers), application promotion (end users), and talent training (vocational education), promoting the iterative upgrade of HRC technologies through industry–university–research cooperation and the commercialization of innovative achievements.

- Optimize energy consumption through intelligent energy management algorithms, such as scheduling robot working hours based on production peaks and valleys, selecting energy-efficient motion paths via path planning, and enabling standby energy-saving modes for idle equipment;

- Integrate HRC technologies with circular economy concepts, such as collaborative disassembly and remanufacturing of waste products through human–robot collaboration, and real-time monitoring of carbon emissions in the production process based on digital twins, contributing to the green transformation of the manufacturing industry.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leng, J.; Sha, W.; Wang, B.; Zheng, P.; Zhuang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wuest, T.; Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. Industry 5.0: Prospect and retrospect. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tao, F.; Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Freiheit, T. Smart Manufacturing and Intelligent Manufacturing: A Comparative Review. Engineering 2021, 7, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, R.; Zheng, P.; Wang, L. Towards proactive human–robot collaboration: A foreseeable cognitive manufacturing paradigm. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietanen, A.; Pieters, R.; Lanz, M.; Latokartano, J.; Kämäräinen, J.-K. AR-based interaction for human-robot collaborative manufacturing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 63, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, Y.Y.; Ryu, K. Task Allocation in Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC) Based on Task Characteristics and Agent Capability for Mold Assembly. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J. HRC for dual-robot intelligent assembly system based on multimodal perception. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 238, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankemeyer, S.; Wendorff, D.; Raatz, A. A hand-interaction model for augmented reality enhanced human-robot collaboration. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Nicoletti, L. Digital twin for human-robot collaboration enhancement in manufacturing systems: Literature review and direction for future developments. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, P.; Fei, B.; Xu, Z. Dynamic scenario-enhanced diverse human motion prediction network for proactive human–robot collaboration in customized assembly tasks. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 4593–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Vision language model-enhanced embodied intelligence for digital twin-assisted human-robot collaborative assembly. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 48, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, F.; Zou, Z.; Duffy, V.G. Application, Development and Future Opportunities of Collaborative Robots (Cobots) in Manufacturing: A Literature Review. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzoldt, C.; Niermann, D.; Maack, E.; Sontopski, M.; Vur, B.; Freitag, M. Implementation and Evaluation of Dynamic Task Allocation for Human–Robot Collaboration in Assembly. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchettin, A.M.; Casalino, A.; Piroddi, L.; Rocco, P. Prediction of human activity patterns for human–robot collaborative assembly tasks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics. 2018, 15, 3934–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, G.; Antonelli, D. Dynamic task classification and assignment for the management of human-robot collaborative teams in workcells. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 98, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, T.; Jun, H.; Shin, D. Task Allocation in Human–Machine Manufacturing Systems Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yang, R.; Zhao, K.; Yu, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L. Hybrid Convolutional Neural Network Approaches for Recognizing Collaborative Actions in Human–Robot Assembly Tasks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavsar, M.; Deni, M.; Nemec, B.; Ude, A. Intention Recognition with Recurrent Neural Networks for Dynamic Human-Robot Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 6–10 December 2021; pp. 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Gao, R.X. Deep learning-based human motion recognition for predictive context-aware human-robot collaboration. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi, C.; Thomas, U. Skeleton-based Action Recognition for Human-Robot Interaction using Self-Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021), Jodhpur, India, 15–18 December 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Yan, L.; Wang, G.; Gerada, C. Hybrid Recurrent Neural Network Architecture-Based Intention Recognition for Human–Robot Collaboration. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Bilberg, A. Complexity-based task allocation in human-robot collaborative assembly. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2019, 46, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barathwaj, N.; Raja, P.; Gokulraj, S. Optimization of assembly line balancing using genetic algorithm. J. Cent. South Univ. 2015, 22, 3957–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Lv, Q.; Bao, J.; Li, J. A digital twin-driven human–robot collaborative assembly-commissioning method for complex products. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L. A transfer reinforcement learning and digital-twin based task allocation method for human-robot collaboration assembly. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, N.; Kaipis, M.; Giartzas, S.; Michalos, G. Generative AI for automated task modelling and task allocation in human robot collaborative applications. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Patel, S.; Evans, A.; Pimley, J.; Li, Y.; Kovalenko, I. Enhancing Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly in Manufacturing Systems Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Bari, Italy, 28 August–1 September 2024; pp. 2581–2587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.; Yan, Y.; Wang, L. Perception-decision-execution coordination mechanism driven dynamic autonomous collaboration method for human-like collaborative robot based on multimodal large language model. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2026, 98, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, S.; Xu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, G. Human-robot Autonomous Collaboration Method of Smart Manufacturing Systems Based on Large Language Model and Machine Vision. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 61, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, Y. Human-Machine Interactive Collaborative Decision-Making Based on Large Model Technology: Application Scenarios and Future Developments. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technology (ICAIDT), Guangzhou, China, 28–30 April 2025; pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, F.; Gao, T.; Li, H.; Lu, Z. Research on Human-robot Joint Task Assignment Considering Task Complexity. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 57, 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bilberg, A.; Malik, A.A. Digital twin driven human–robot collaborative assembly. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wang, G.; Luo, X.; Xu, X. Task allocation of human-robot collaborative assembly line considering assembly complexity and workload balance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 4749–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Z. Intelligent Robotic Assembly Method of Spaceborne Equipment Based on Visual Guidance. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 54, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Digital Twin-based Design and Operation of Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeman, W.C.; Kapoor, R.; Ghosh, P. Multimodal Classification: Current Landscape, Taxonomy and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, B.; Fu, H. Advanced Design of Soft Robots with Artificial Intelligence. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Khan, S.U.; Rida, I.; Khan, N.; Baik, S.W. Human centric attention with deep multiscale feature fusion framework for activity recognition in Internet of Medical Things. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, K.; Hui, J.; Liu, S.; Guo, W.; Wang, L. Skeleton-RGB integrated highly similar human action prediction in human–robot collaborative assembly. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piardi, L.; Leitão, P.; Queiroz, J.; Pontes, J. Role of digital technologies to enhance the human integration in industrial cyber–physical systems. Annu. Rev. Control. 2024, 57, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Sohail, S.S.; Javed, L.; Anwer, F.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Muhammad, K. Vision-Enabled Large Language and Deep Learning Models for Image-Based Emotion Recognition. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 2566–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazmoune, S.; Bougamouza, F. Using transformers for multimodal emotion recognition: Taxonomies and state of the art review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoudh, K. A survey of multimodal hybrid deep learning for computer vision: Architectures, applications, trends, and challenges. Inf. Fusion 2024, 105, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Alinezhad, A.; Vahdani, B. A deep learning framework for quality control process in the motor oil industry. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Rocco, P.; Zanchettin, A.M.; Zhao, F.; Jiang, G.; Mei, X. A real-time hierarchical control method for safe human–robot coexistence. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.Q.; Li, C.X.; Zhang, C.B.; Liu, S.M.; Zheng, P. Leveraging error-assisted fine-tuning large language models for manufacturing excellence. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 88, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. A transformer-encoder-based multimodal multi-attention fusion network for sentiment analysis. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 8415–8441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salichs, M.A.; Castro-González, Á.; Salichs, E.; Fernández-Rodicio, E.; Maroto-Gómez, M.; Gamboa-Montero, J.J.; Marques-Villarroya, S.; Castillo, J.C.; Alonso-Martín, F.; Malfaz, M. Mini: A New Social Robot for the Elderly. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Ross, H.; Sulem, E.; Veyseh, A.P.B.; Nguyen, T.H.; Sainz, O.; Agirre, E.; Heintz, I.; Roth, D. Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing via Large Pre-trained Language Models: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Feng, B.; Huo, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Peng, J.; Li, Z.; Du, C.; Wang, W.; Zou, G.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Meets Flexible Sensors: Emerging Smart Flexible Sensing Systems Driven by Machine Learning and Artificial Synapses. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; He, G.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Lu, W. Re-examining lexical and semantic attention: Dual-view graph convolutions enhanced BERT for academic paper rating. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, R.; Liu, J.; Tang, X. A text guided multi-task learning network for multimodal sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing 2023, 560, 126836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadegan, F.; Naghsh-Nilchi, A.R.; Shabaninia, E. Multimodal vision-based human action recognition using deep learning: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Q.; Pan, Y.; Ding, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Xie, Y. Multi-level correlation mining framework with self-supervised label generation for multimodal sentiment analysis. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Wang, X.V. Data-efficient multimodal human action recognition for proactive human–robot collaborative assembly: A cross-domain few-shot learning approach. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xie, Q.; Pei, J.; Chen, Z.; Tiwari, P.; Li, Z.; Fu, J. Pre-trained Language Models in Biomedical Domain: A Systematic Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yin, C. More than a framework: Sketching out technical enablers for natural language-based source code generation. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 53, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplaza, J.; Moreno, F.; Sanfeliu, A. Enhancing Robotic Collaborative Tasks Through Contextual Human Motion Prediction and Intention Inference. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2025, 17, 2077–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Reinforcement learning with imitative behaviors for humanoid robots navigation: Synchronous planning and control. Auton. Robot. 2024, 48, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, D.; Leng, Y.; Rong, Y.; Huang, G.Q. RHYTHMS: Real-time Data-driven Human-machine Synchronization for Proactive Ergonomic Risk Mitigation in the Context of Industry 4.0 and Beyond. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 87, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chen, Z.; Du, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, S. VisPower: Curriculum-Guided Multimodal Alignment for Fine-Grained Anomaly Perception in Power Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, S.; Karimi, H.R. Zoom-Anomaly: Multimodal vision-Language fusion industrial anomaly detection with synthetic data. Inf. Fusion 2026, 127, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Hu, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Human—Machine augmented intelligence: Research and applications. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2022, 23, 1139–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, K.; Sudhakar, G.; Xavier, K.F.; Bharathiraja, N.; Kaur, G. Human-machine interaction in mechanical systems through sensor enabled wearable augmented reality interfaces. Meas. Sens. 2025, 39, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Han, D.; Chen, Y.; Tian, F.; Wang, H.; Dai, G. A Survey on Human-Computer Interaction in Mixed Reality. J. Comput.-Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 2016, 28, 869–880. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Sun, B.; Zhao, S.; Dai, K.; Zhao, H.; Wu, J. Research on the Human-machine Hybrid Decision-making Strategy Basing on the Hybrid-augmented Intelligence. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 61, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Liu, J.; Jia, X.; Qie, J. An assisted assembly method based on augmented reality. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Sesmero, R.; Lozano-Hernández, A.; Frontela-Encinas, F.; Cabezas-López, G.; De-Diego-Moro, M. Human–Robot Interaction and Tracking System Based on Mixed Reality Disassembly Tasks. Robotics 2025, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Gu, C. An Aircraft Part Assembly Based on Virtual Reality Technology and Mixed Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Big Data Analytics for Cyber-Physical System in Smart City, Singapore, 10 December 2021; pp. 1251–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Hongli, S.; Qingmiao, W. Research on AR assisted aircraft maintenance technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1738, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Bai, G.; Tang, C. An Augmented Reality Tracking Registration Method Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition, Xiamen, China, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Q. Research on Satellite Cable Laying and Assembly Guidance Technology Based on Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 40th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 6550–6555. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, J.; Bianchi, M.; Ferrari, V. Integrated Haptic Feedback with Augmented Reality to Improve Pinching and Fine Moving of Objects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, Ö.K.; Karabulut, Ş.; Höke, G. Effect of Virtual Reality-Based Training on Complex Industrial Assembly Task Performance. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 12697–12708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masehian, E.; Ghandi, S. Assembly sequence and path planning for monotone and nonmonotone assemblies with rigid and flexible parts. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 72, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, K.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Ming, S.; He, Z. Application of Embodied Interaction Technology in Virtual Assembly Training. Packag. Eng. 2025, 46, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard, V.; Jeanne, B.; Lacomblez, M.; Baudry, D. Digital twin and virtual reality: A co-simulation environment for design and assessment of industrial workstations. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2019, 7, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, S.; He, W.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, L. A novel mixed reality remote collaboration system with adaptive generation of instructions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 194, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetohul, J.; Shafiee, M.; Sirlantzis, K. Augmented Reality (AR) for Surgical Robotic and Autonomous Systems: State of the Art, Challenges, and Solutions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Meng, X.; Lu, G.; Hou, L.; Minzhe, N.; Liang, X.; Yao, L.; Huang, R.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; et al. Wukong: A 100 million large-scale chinese cross-modal pre-training benchmark. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 26418–26431. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-VL: A Versatile Vision-Language Model for Understanding, Localization, Text Reading, and Beyond. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12966. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Wan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dong, C.; Li, W.; Lin, Y. Improving BERT with local context comprehension for multi-turn response selection in retrieval-based dialogue systems. Comput. Speech Lang. 2023, 82, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, Z.R.; Pai, Y.-T.; Lee, Y.-W.J.A. VisTW: Benchmarking Vision-Language Models for Traditional Chinese in Taiwan. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10427. [Google Scholar]

- Krupas, M.; Kajati, E.; Liu, C.; Zolotova, I. Towards a Human-Centric Digital Twin for Human–Machine Collaboration: A Review on Enabling Technologies and Methods. Sensors 2024, 24, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Langås, E.F.; Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergies between collaborative robotics, digital twins, augmentation, and industry 5.0 for smart manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piardi, L.; Queiroz, J.; Pontes, J.; Leitão, P. Digital Technologies to Empower Human Activities in Cyber-Physical Systems. IFAC-Pap. 2023, 56, 8203–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Park, K.-B.; Roh, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Mohammed, M.; Ghasemi, Y.; Jeong, H. An integrated mixed reality system for safety-aware human-robot collaboration using deep learning and digital twin generation. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X. Foundation models assist in human–robot collaboration assembly. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chu, H.; Zou, Y.; Sun, H. A robust electromyography signals-based interaction interface for human-robot collaboration in 3D operation scenarios. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Z. Human Digital Twin for Real-Time Physical Fatigue Estimation in Human-Robot Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Bristol, UK, 25–27 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.A.; Bilberg, A. Digital twins of human robot collaboration in a production setting. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 17, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröder, K.; Bobka, P.; Germann, T.; Gabriel, F.; Dietrich, F. A Machine Learning-Enhanced Digital Twin Approach for Human-Robot-Collaboration. Procedia CIRP 2018, 76, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousi, N.; Gkournelos, C.; Aivaliotis, S.; Lotsaris, K.; Bavelos, A.C.; Baris, P.; Michalos, G.; Makris, S. Digital Twin for Designing and Reconfiguring Human–Robot Collaborative Assembly Lines. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchane Djogdom, G.V.; Meziane, R.; Otis, M.J.D. Robust dynamic robot scheduling for collaborating with humans in manufacturing operations. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 88, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyekan, J.O.; Hutabarat, W.; Tiwari, A.; Grech, R.; Aung, M.H.; Mariani, M.P.; López-Dávalos, L.; Ricaud, T.; Singh, S.; Dupuis, C. The effectiveness of virtual environments in developing collaborative strategies between industrial robots and humans. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 55, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.J.; Han, J.H.; Zhang, Z.L.; Fan, L.F.; Liu, T.Y.; Qi, S.Y.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhu, S.C. The Tong Test: Evaluating Artificial General Intelligence Through Dynamic Embodied Physical and Social Interactions. Engineering 2024, 34, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, W.; Ye, Q.; Popa, D.; Zhang, Y. Human-robot collaborative assembly and welding: A review and analysis of the state of the art. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 1388–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.B.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.M.; Bao, J.S. Adaptive planning of human-robot collaborative disassembly for end-of-life lithium-ion batteries based on digital twin. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 2021–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasik-Duncan, B.J.I.C.S. Adaptive Control [Second edition, by Karl J. Astrom and Bjorn Wittenmark, Addison Wesley (1995)]. IEEE Control. Syst. Mag. 2002, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, B. A review on model reference adaptive control of robotic manipulators. Annu. Rev. Control. 2017, 43, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, J. Multimodal perception-fusion-control and human–robot collaboration in manufacturing: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Yu, L.; Su, X.; Wen, Y.; Dai, X. Adaptive hybrid impedance control for dual-arm cooperative manipulation with object uncertainties. Automatica 2022, 140, 110232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, B.; He, W.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, L.; Silvestre, C. Adaptive-Constrained Impedance Control for Human–Robot Co-Transportation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 13237–13249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A.; Ordys, A.; Możaryn, J.; Sibilska-Mroziewicz, A. Control System Design and Methods for Collaborative Robots: Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Peng, J.; Xin, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Task-Oriented Adaptive Position/Force Control for Robotic Systems Under Hybrid Constraints. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 12612–12622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-I.; Shodiq, M.A.F.; Hsieh, M.F. Robot path planning based on three-dimensional artificial potential field. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wu, L.; Huang, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, C.; Xiao, W. Multi-strategy adaptable ant colony optimization algorithm and its application in robot path planning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 288, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Pang, H.; He, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, T. Path Planning of Autonomous Mobile Robot in Comprehensive Unknown Environment Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 22153–22166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L. Path planning algorithm of robot arm based on improved RRT* and BP neural network algorithm. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, M.G.; Salgoankar, A. A survey of robotic motion planning in dynamic environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 100, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhou, H.; Xu, T. Obstacle avoidance path planning of 6-DOF robotic arm based on improved A* algorithm and artificial potential field method. Robotica 2024, 42, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Mao, H.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, T. A novel RRT*-Connect algorithm for path planning on robotic arm collision avoidance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Tateo, D.; Liu, P.; Peters, J. Adaptive Control Based Friction Estimation for Tracking Control of Robot Manipulators. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 2454–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhan, G.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Rao, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Adaptive impedance control for docking robot via Stewart parallel mechanism. ISA Trans. 2024, 155, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, M.; Buchli, J.; Caldwell, D.G. Code generation of algebraic quantities for robot controllers. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2346–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Lyu, C. Multi-stage guided code generation for Large Language Models. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.F. No Need to Lift a Finger Anymore? Assessing the Quality of Code Generation by ChatGPT. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2024, 50, 1548–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.; Jain, A.; Go, K.; Xia, F.; Stark, M.; Schaal, S.; Hausman, K. GenCHiP: Generating Robot Policy Code for High-Precision and Contact-Rich Manipulation Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 9596–9603. [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso, A.; Cote, N.; Chitta, S. Toward Automated Programming for Robotic Assembly Using ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 17687–17693. [Google Scholar]

- Tocchetti, A.; Corti, L.; Balayn, A.; Yurrita, M.; Lippmann, P.; Brambilla, M.; Yang, J.A.I. Robustness: A Human-Centered Perspective on Technological Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, L.I.; Ke, W.; Biao, W.; Ziqi, Z.; Yafei, L.I.; Yibo, G.U.O.; Yazhou, H.U.; Hua, W.; Pei, L.V.; Mingliang, X.U. Human-Machine Fusion Intelligent Decision-Making: Concepts, Framework, and Applications. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2025, 47, 3439–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Amodei, D. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.R.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.-l.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.-B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 18, 186345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hasler, S.; Tanneberg, D.; Ocker, F.; Joublin, F. LaMI: Large Language Models Driven Multi-Modal Interface for Human-Robot Communication. In Proceedings of the CHI EA ‘24: Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 11–16 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, R.; Chen, L.; Feng, Z.; Liu, J.; Feng, S. Fine-tuned Multimodal Large Language Models are Zero-shot Learners in Image Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Nantes, France, 30 June–4 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Che, X.; Chu, M.; Chen, Y.; Gu, H.; Li, Q. Chain-of-thought driven dynamic prompting and computation method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2026, 186, 114204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Sadigh, D.; Sastry, S.; Seshia, S.; Dragan, A. Planning for Autonomous Cars that Leverage Effects on Human Actions. In Robotics: Science And Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, A.Y.; Russell, S. Algorithms for Inverse Reinforcement Learning. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, R.; Wu, Y.; Tamar, A.; Harb, J.; Abbeel, P.; Mordatch, I.J.A. Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02275. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T.; Samvelyan, M.; Witt, C.S.D.; Farquhar, G.; Foerster, J.; Whiteson, S. Monotonic value function factorisation for deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Wu, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, B.; Jiang, Y. Object Recognition and Grasping for Collaborative Robots Based on Vision. Sensors 2024, 24, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzoldt, C.; Harms, M.; Freitag, M. Review of task allocation for human-robot collaboration in assembly. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 36, 1675–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamon, E.; Fusaro, F.; De Momi, E.; Ajoudani, A. A Unified Architecture for Dynamic Role Allocation and Collaborative Task Planning in Mixed Human-Robot Teams. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.08038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.K.; Jain, S.; Romeres, D.; Yerazunis, W.; Nikovski, D. Generalizable Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly Using Imitation Learning and Force Control. In Proceedings of the 2023 European Control Conference (ECC), Bucharest, Romania, 13–16 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, T.; Dong, W.; Zheng, P.; Wang, L. Vision-language model-based human-robot collaboration for smart manufacturing: A state-of-the-art survey. Front. Eng. Manag. 2025, 12, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liu, L. et al. (2024) [11] | PRISMA |

| 2 | Petzoldt, C. et al. (2022) [12] | HRC |

| 3 | Malik, A.A. et al. (2019) [13] | complexity-based tasks classification |

| 4 | Bruno, G. et al. (2018) [14] | task classification |

| 5 | Joo, T. et al. (2022) [15] | deep reinforcement learning |

| 6 | Gao, Z. et al. (2024) [16] | CNN |

| 7 | Mavsar, M. et al. (2021) [17] | RNN |

| 8 | Wang, P. et al. (2018) [18] | deep learning |

| 9 | Bandi, C. et al. (2021) [19] | RNN, CNN |

| 10 | Malik, A.A. et al. (2019) [20] | complexity-based tasks classification |

| 11 | Gao, X. et al. (2021) [21] | RNN |

| 12 | Barathwaj, N. et al. (2015) [22] | RULA, problem based genetic algorithm (GA) |

| 13 | Sun, X. et al. (2022) [23] | RULA, digital twin |

| 14 | Wang, J. et al. (2025) [24] | transfer reinforcement learning, augmented reality |

| 15 | Dimitropoulos, N. et al. (2025) [25] | LLM, digital twin |

| 16 | Lim, J. et al. (2024) [26] | LLM |

| 17 | Chen, J. et al. (2026) [27] | MLLM |

| 18 | Sihan, H. et al. (2025) [28] | LLM |

| 19 | Liu, Z. et al. (2025) [29] | LLM |

| 20 | Kong, F. et al. (2021) [30] | LLM |

| 21 | Bilberg, A. et al. (2019) [31] | LLM, digital twin |

| 22 | Cai, M. et al. (2025) [32] | LLM |

| 23 | Xuquan, J.I. et al. (2018) [33] | LLM |

| 24 | Wang, Y. et al. (2022) [34] | LLM |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sleeman et al. (2022) [35] | Multimodal classification taxonomy |

| 2 | Cao et al. (2024) [36] | Multimodal soft sensors |

| 3 | Hussain et al. (2024) [37] | Deep multiscale feature fusion |

| 4 | Zhang et al. (2024) [38] | Skeleton-RGB integrated action prediction |

| 5 | Piardi et al. (2024) [39] | Human-in-the-Mesh (HitM) integration |

| 6 | Nadeem et al. (2024) [40] | Vision-Enabled Large Language Models (LLMs) |

| 7 | Hazmoune et al. (2024) [41] | Transformers |

| 8 | Bayoudh, K. (2024) [42] | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) |

| 9 | Heydari et al. (2024) [43] | Residual Networks (ResNet) |

| 10 | Liu et al. (2024) [44] | Hierarchical control method |

| 11 | Zhang et al. (2024) [45] | Human mesh recovery algorithm |

| 12 | Liu et al. (2024) [46] | Transformer-encoder |

| 13 | Salichs et al. (2020) [47] | Social robot platform |

| 14 | Min et al. (2023) [48] | Large Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) |

| 15 | Sun et al. (2023) [49] | Flexible sensors |

| 16 | Xue et al. (2023) [50] | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) |

| 17 | Luo et al. (2023) [51] | Text guided multi-task learning network |

| 18 | Shafizadegan et al. (2024) [52] | Feature-level fusion |

| 19 | Li et al. (2023) [53] | Self-supervised label generation (Self-MM) |

| 20 | Wang et al. (2024) [54] | Cross-domain few-shot learning (CDMFL) |

| 21 | Wang et al. (2023) [55] | Multimodal Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) |

| 22 | Yang et al. (2024) [56] | Natural language-based code generation |

| 23 | Laplaza et al. (2025) [57] | Contextual human motion prediction |

| 24 | Wang et al. (2024) [58] | Reinforcement learning with imitative behaviors |

| 25 | Ling et al. (2024) [59] | Real-time data-driven human–machine synchronization (RHYTHMS) |

| 26 | Yan, H. et al. (2025) [60] | Curriculum-guided multimodal alignment |

| 27 | Li, J. et al. (2026) [61] | Synthetic anomaly generation (Zoom-Anomaly) |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xue et al. (2022) [62] | a review |

| 2 | Balamurugan et al. (2025) [63] | wearable sensor-based AR interfaces |

| 3 | Huang et al. (2016) [64] | a review |

| 4 | Ma et al. (2025) [65] | the proposed human–machine hybrid decision-making strategy |

| 5 | Bao et al. (2024) [66] | LK optical flow registration |

| 6 | Calderón-Sesmero et al. (2025) [67] | deep learning |

| 7 | Dong et al. (2022) [68] | VR, MR |

| 8 | Yuan et al. (2021) [69] | AR |

| 9 | Yan et al. (2022) [70] | deep learning in AR |

| 10 | Yang et al. (2021) [71] | AR |

| 11 | Hamad et al. (2025) [72] | AR, VR |

| 12 | Kalkan et al. (2021) [73] | VR |

| 13 | Masehian et al. (2021) [74] | SPP-Flex |

| 14 | Yan et al. (2025) [75] | a review |

| 15 | Havard et al. (2019) [76] | a co-simulation and communication architecture between digital twin and virtual reality software |

| 16 | Zhang et al. (2024) [77] | MR |

| 17 | Seetohul et al. (2023) [78] | AR |

| 18 | Gu et al. (2022) [79] | a review |

| 19 | Bai et al. (2023) [80] | Vision-language model |

| 20 | Chen et al. (2023) [81] | BERT-LCC |

| 21 | Tam et al. (2025) [82] | VisTW |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Krupas et al. (2024) [83] | Technology & method review |

| 2 | Zafar et al. (2024) [84] | State-of-the-art review |

| 3 | Piardi et al. (2023) [85] | Digital technologies |

| 4 | Choi et al. (2022) [86] | Deep learning |

| 5 | Tao et al. (2022) [87] | Digital twin modeling |

| 6 | Ji et al. (2024) [88] | LLMs, VFMs |

| 7 | Tie et al. (2024) [89] | R3DNet |

| 8 | You et al. (2024) [90] | IK-BiLSTM-AM |

| 9 | Malik et al. (2018) [91] | Tecnomatix Process Simulate |

| 10 | Dröder et al. (2018) [92] | ANN, obstacle detection |

| 11 | Kousi et al. (2021) [93] | optimization algorithms |

| 12 | Tchane Djogdom et al. (2024) [94] | Robust dynamic scheduling |

| 13 | Oyekan et al. (2019) [95] | Digital twin |

| 14 | Liu et al. (2024) [96] | Web-based digital twin |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cao et al. (2024) [97] | a review |

| 2 | Li et al. (2024) [98] | a review |

| 3 | Astrom et al. (1994) [99] | Adaptive Control |

| 4 | Zhang et al. (2017) [100] | a review |

| 5 | Duan et al. (2024) [101] | MMI |

| 6 | Jiao et al. (2022) [102] | AHIC |

| 7 | Yu et al. (2022) [103] | ACIC |

| 8 | Hameed et al. (2023) [104] | a review |

| 9 | Ding et al. (2024) [105] | TOAPFC |

| 10 | Lin et al. (2025) [106] | improved 3D APF |

| 11 | Cui et al. (2024) [107] | MsAACO |

| 12 | Bai et al. (2024) [108] | IDDQN |

| 13 | Gao et al. (2023) [109] | BP-RRT |

| 14 | Mohanan et al. (2018) [110] | a review |

| 15 | Tang et al. (2024) [111] | improved A* |

| 16 | Cao et al. (2025) [112] | RRT-Connect |

| 17 | Huang et al. (2025) [113] | ARIC |

| 18 | Chen et al. (2024) [114] | Stewart Parallel Mechanism |

| 19 | Frigerio et al. (2012) [115] | DSLs |

| 20 | Han et al. (2025) [116] | LLMs |

| 21 | Liu et al. (2024) [117] | LLMs |

| 22 | Burns et al. (2024) [118] | LLMs |

| 23 | Macaluso et al. (2024) [119] | LLMs |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tocchetti et al. (2025) [120] | ML |

| 2 | Zhe et al. (2025) [121] | method review |

| 3 | Rane et al. (2023) [122] | LLM |

| 4 | Sobo et al. (2023) [123] | MLLM |

| 5 | Team et al. (2023) [124] | LLM |

| 6 | Wang et al. (2024) [125] | LLM |

| 7 | Wang et al. (2024) [126] | LLM |

| 8 | Xiong et al. (2025) [127] | MLLM |

| 9 | Che et al. (2026) [128] | DPC-CoT |

| 10 | Ribeiro et al. (2016) [129] | LIME |

| 11 | Lundberg et al. (2017) [130] | SHAP |

| 12 | Sadigh et al. (2016) [131] | IRL |

| 13 | Ng et al. (2024) [132] | IRL |

| 14 | Ouyang et al. (2022) [133] | LLM |

| 15 | Lowe et al. (2017) [134] | RL |

| 16 | Rashid et al. (2020) [135] | QMIXs |

| No. | Authors (Year) | Method |

|---|---|---|

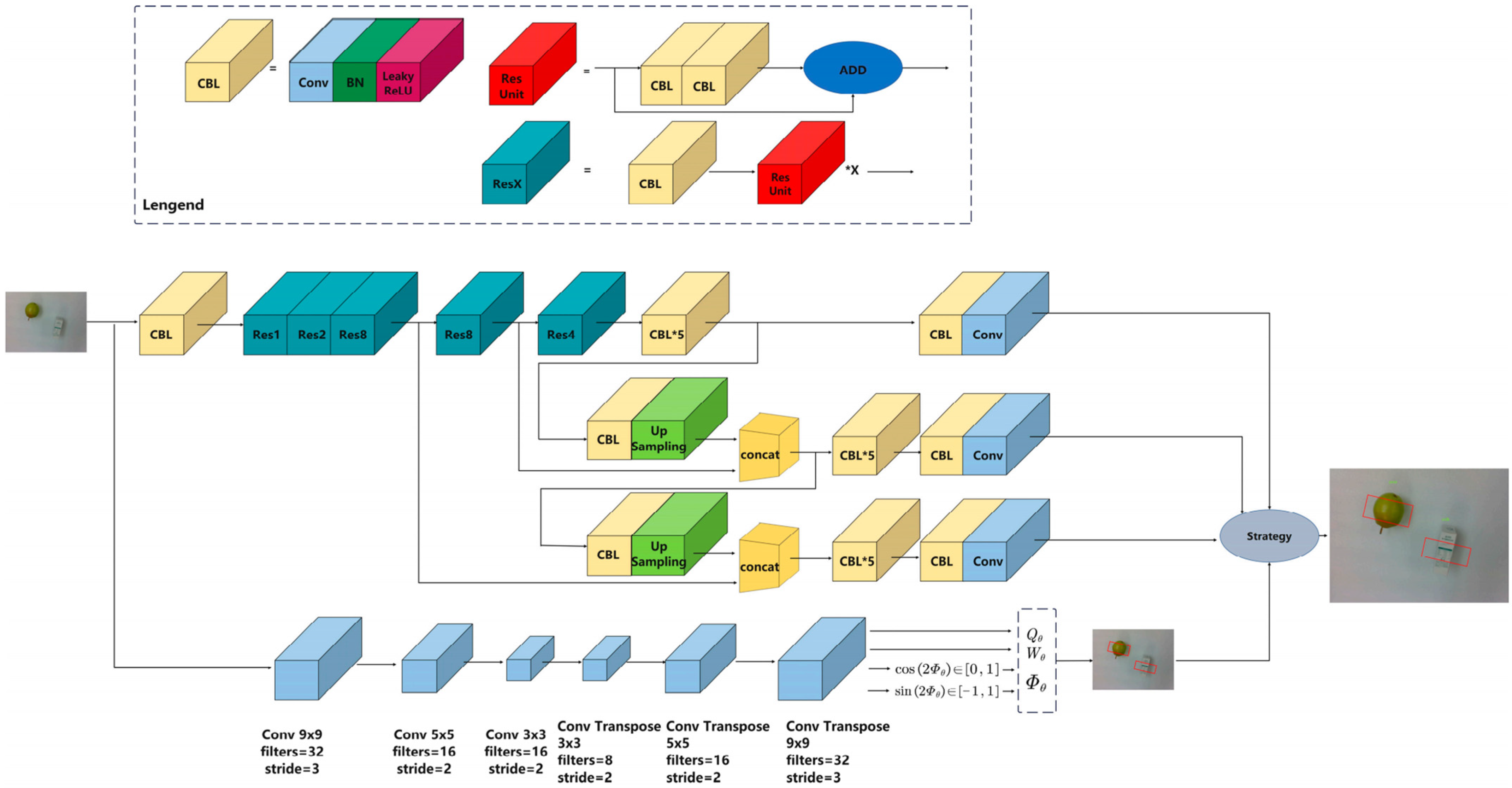

| 1 | Sun et al. (2024) [136] | YOLO-GG |

| 2 | Petzoldt et al. (2023) [137] | a review |

| 3 | Lamon et al. (2023) [138] | behavior trees + MILP |

| 4 | Jha et al. (2023) [139] | imitation learning + force control |

| 5 | Fan et al. (2025) [140] | VLM + deep RL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, Q.; Han, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, S.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Zhu, H. A Comprehensive Review of Human-Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Systems: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends. Sustainability 2026, 18, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010515

Cai Q, Han J, Zhou X, Zhao S, Li L, Liu H, Xu C, Chen J, Liu C, Zhu H. A Comprehensive Review of Human-Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Systems: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010515

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Qixiang, Jinmin Han, Xiao Zhou, Shuaijie Zhao, Lunyou Li, Huangmin Liu, Chenhao Xu, Jingtao Chen, Changchun Liu, and Haihua Zhu. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review of Human-Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Systems: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010515

APA StyleCai, Q., Han, J., Zhou, X., Zhao, S., Li, L., Liu, H., Xu, C., Chen, J., Liu, C., & Zhu, H. (2026). A Comprehensive Review of Human-Robot Collaborative Manufacturing Systems: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends. Sustainability, 18(1), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010515