A Systematic Review of the Practical Applications of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Bridge Structural Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What methods are needed to transform raw SAR data into a useful bridge monitoring procedure? (Q1)

- How does the recurrent application of SAR support SHM? (Q2)

- What challenges prevent SAR from being fully used on its own for bridge SHM? (Q3)

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview

2.2. Systematic Search

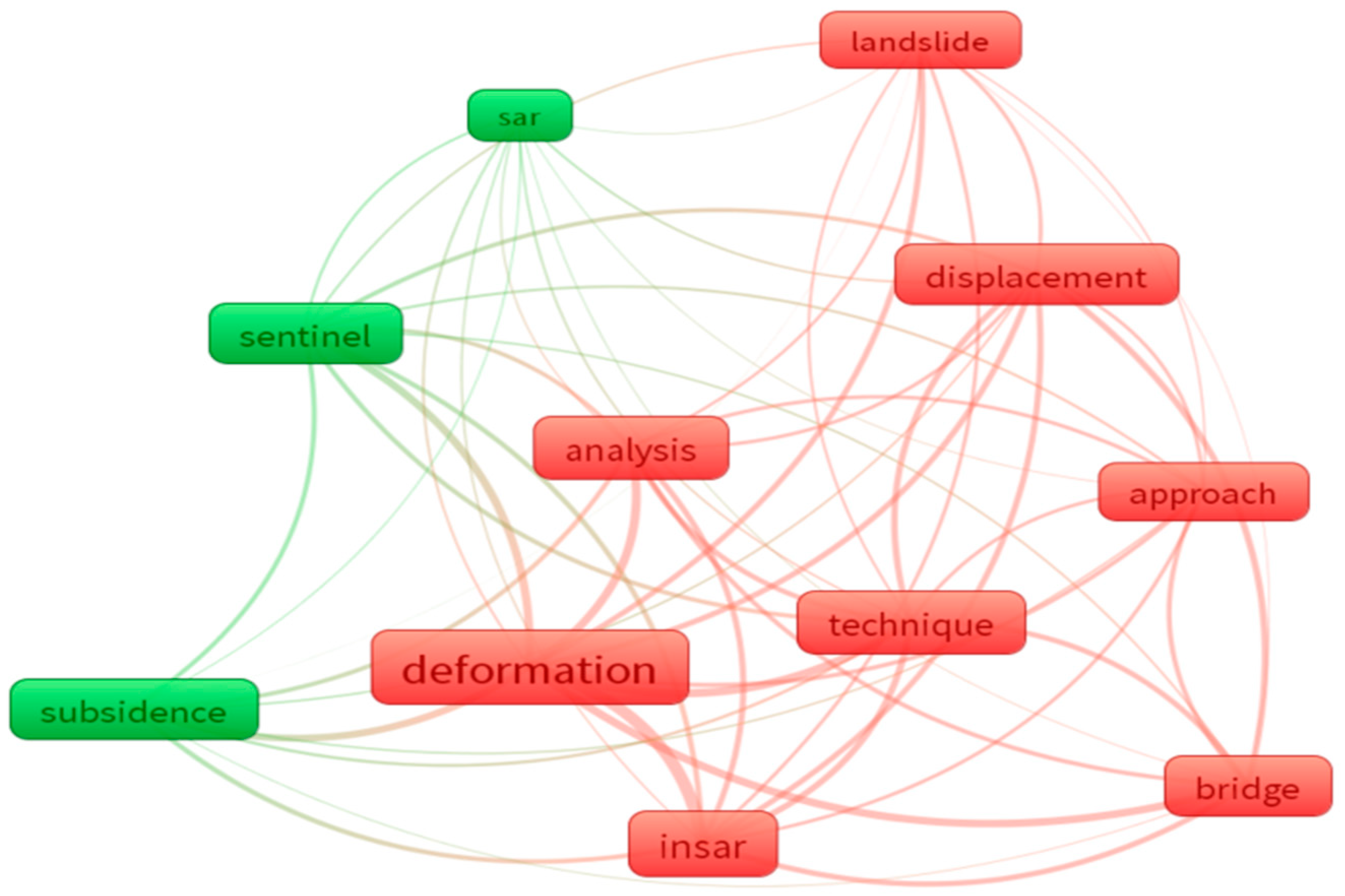

2.3. Science Mapping Review of Keywords in Abstracts

2.4. Bibliometric Analysis of the Number of Citations

3. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1. Performance Review (PR)

3.1.1. PR by Years

3.1.2. PR by Publication Sources

3.1.3. PR by Publication Citations

3.1.4. PR by Publication Authors

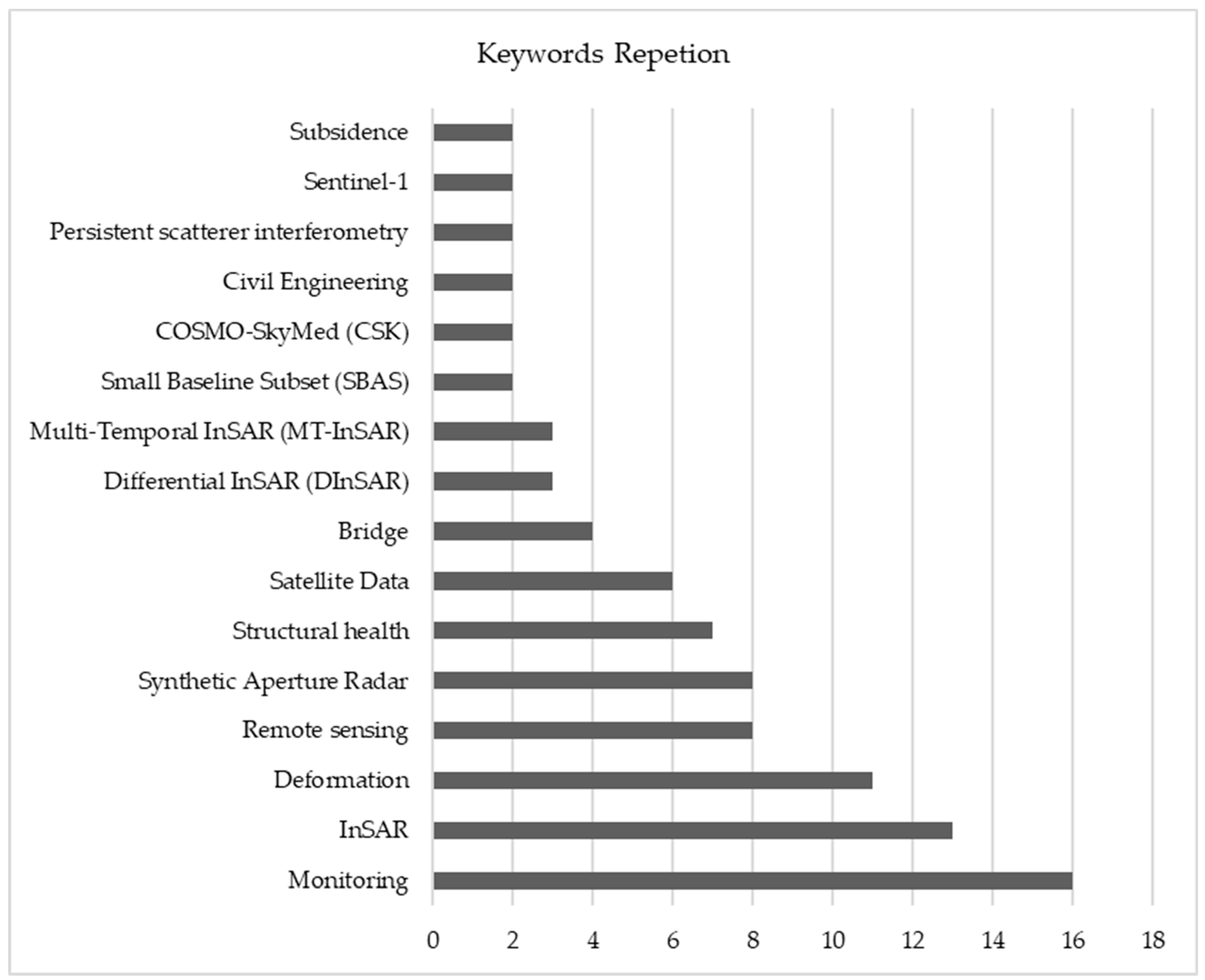

3.1.5. PR by Publication Keywords

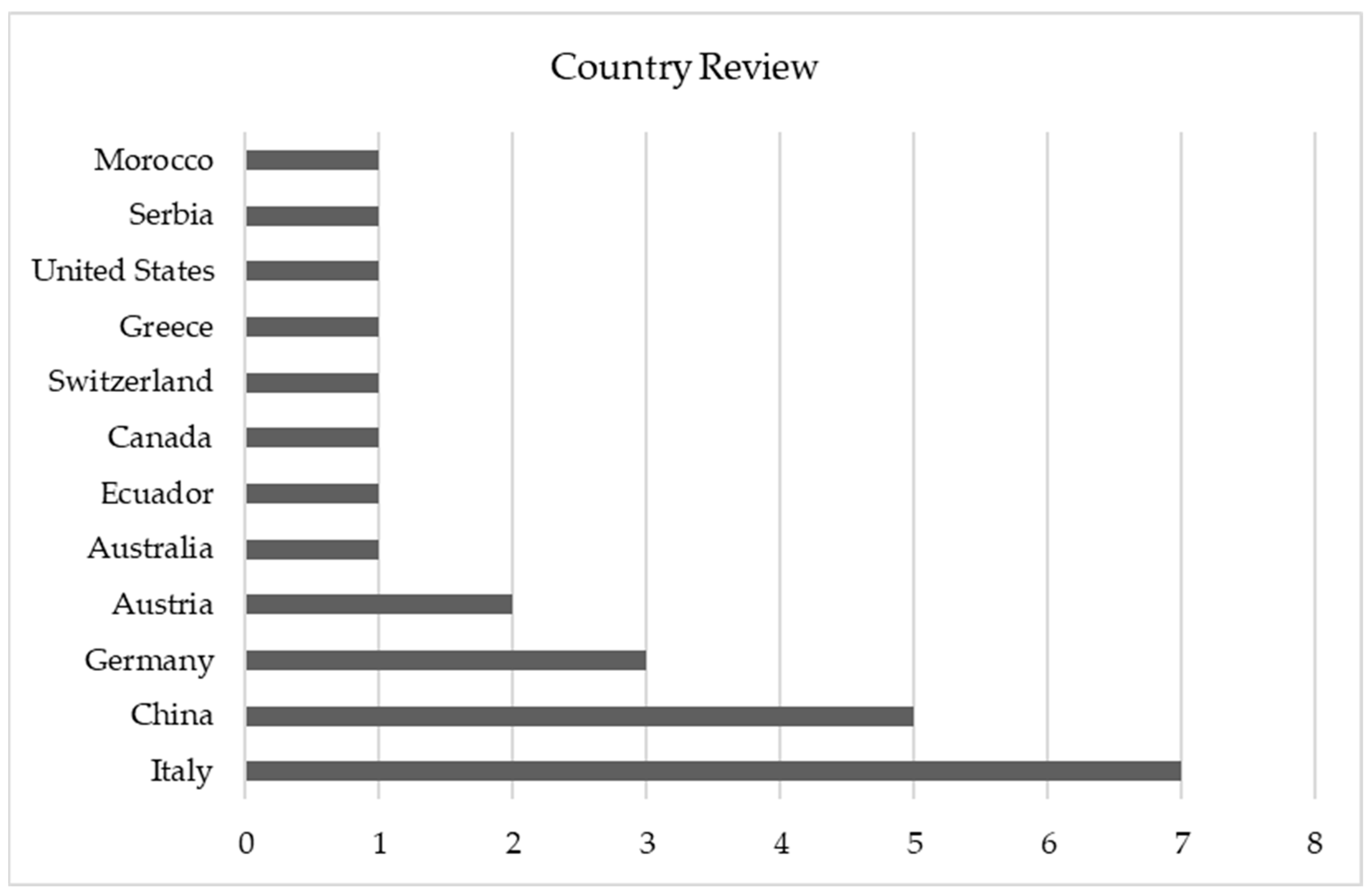

3.1.6. PR by Countries

4. Advancing SAR-Based Bridge Structural Monitoring

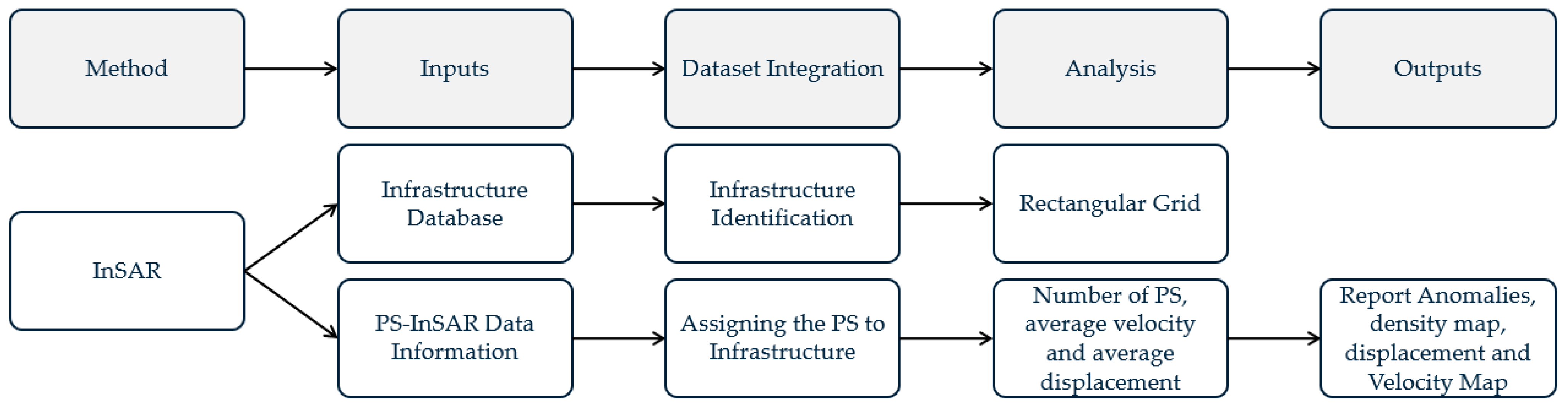

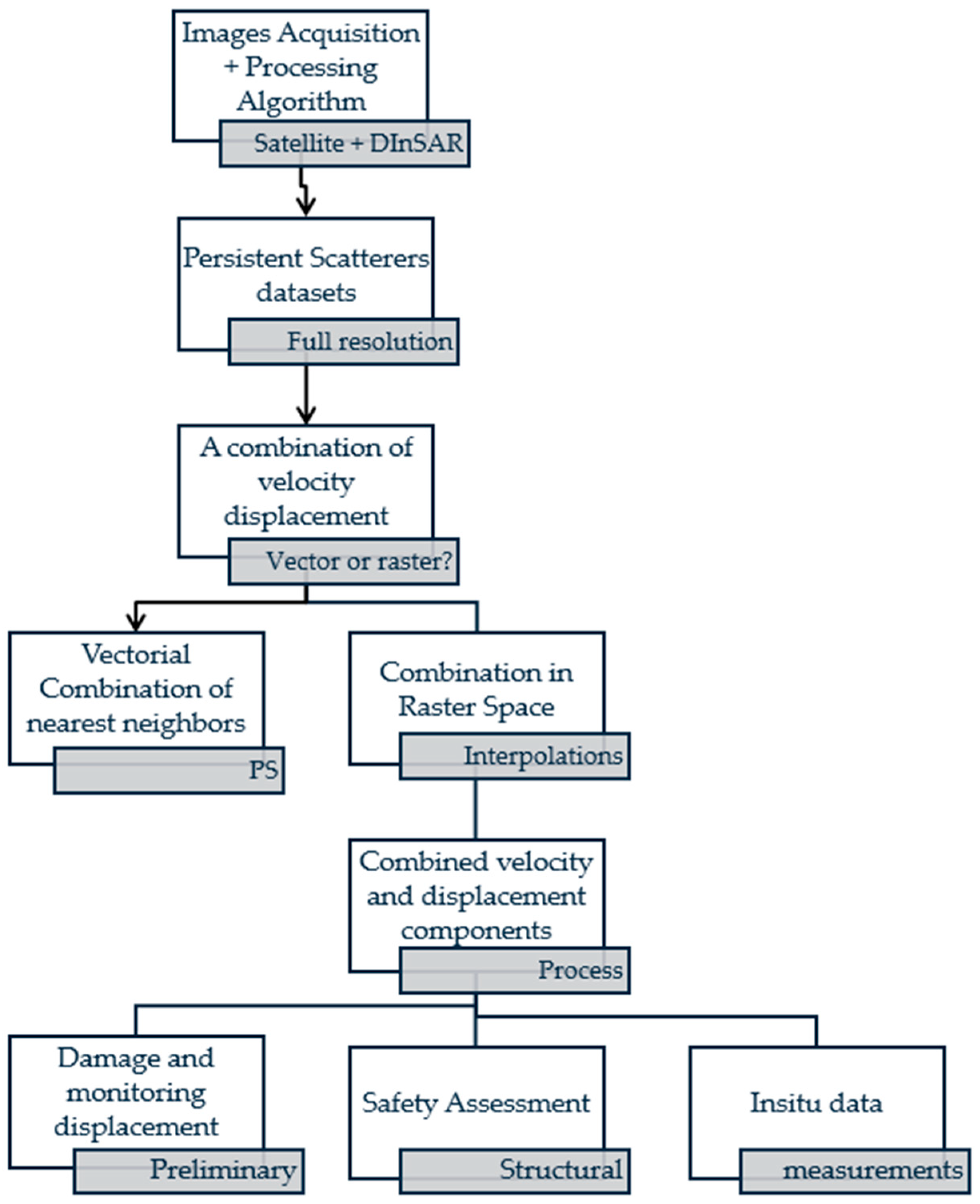

4.1. Methodological Path: From Raw SAR Data to Bridge SHM Indicators (Q1)

4.1.1. Core InSAR Algorithms for Bridge Monitoring

4.1.2. Advanced InSAR Techniques for Bridge Applications

4.1.3. Post-Processing and Engineering Interpretation of InSAR Measurements

4.2. Operational Impact of Recurrent SAR Use on Bridge SHM (Q2)

4.2.1. Value of Recurrent SAR Observations

4.2.2. Integration with Complementary Monitoring Technologies

4.2.3. Risk Indices, GIS, and Network-Level Decision Support

4.2.4. BIM, Digital Twins, and Semantic Interpretation

4.3. Remaining Challenges to Operational Adoption (Q3)

4.3.1. Physical and Measurement Limitations

4.3.2. Data Acquisition Constraints

4.3.3. Signal Quality and Environmental Noise

4.3.4. Interpretation and Automation Gaps

4.3.5. Institutional and Operational Barriers

5. Conclusions

- Long and dense SAR time series images from satellite missions.

- Use of Sentinel-1 for wide coverage or use of COSMO-SkyMed for high resolutions of asset-level detail.

- Presence of stable persistent scatterers (natural or artificial as corner reflectors).

- Multi-orbit data (ascending + descending) to enable various types of displacement decomposition.

- Additional data as temperature records, GNSS, or BIM.

- Method choice should align with structural behaviour.

- The integration of InSAR to correlate surface displacements with internal damage or material degradation from non-destructive testing (NDT).

- The integration of InSAR within GIS to classify bridges by deformation severity and prioritise inspections according to the Satellite-based Bridge Risk Index (SABRI).

- The integration of Satellite-based Analysis for Novelty Detection (SAND) with InSAR data to distinguish thermal motion from damage-induced displacements.

- Complementary components to SAR like the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS), Automated Total Stations (ATSs), corner reflectors (CRs), ground-based SAR (GB-SAR), Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), Airborne and Mobile Laser Scanning (ALS/MLS), Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR), Geographic Information System (GIS), and BRI-GITAL (3D digital twin platform).

- InSAR and MTLS to improve the fidelity of displacement time series and isolate structural trends from environmental noise.

- PSI and BIM models to link PS to specific structural components, enabling component-level health assessment and anomaly detection.

- D-TomoSAR and the Bridge-Adaptive Model to estimate motion, elevation, and thermally induced deformations, for the actual support conditions and geometry of bridges.

- SBAS-InSAR and ESMD to decompose deformation time series into periodic and transient components.

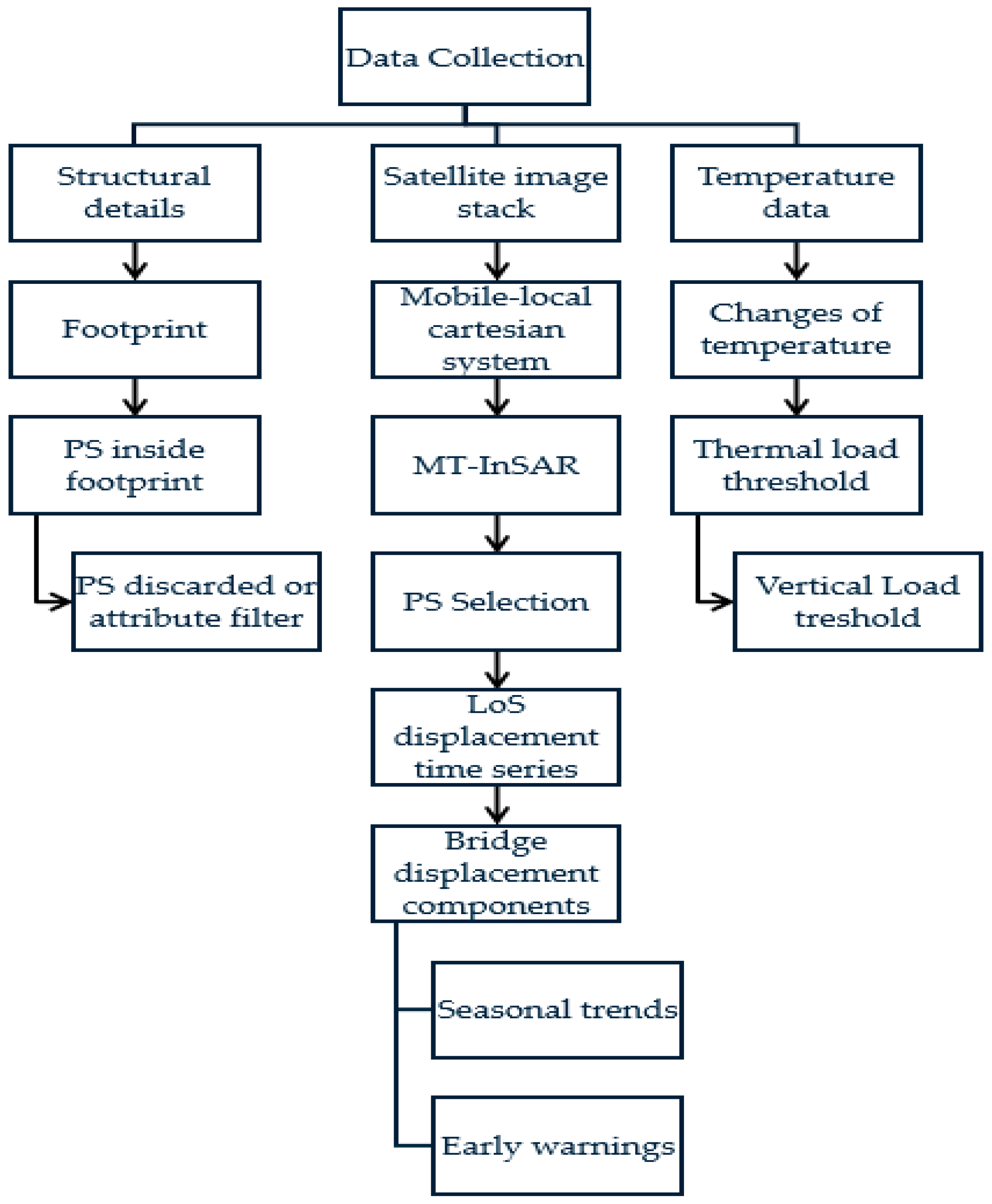

- MT-InSAR, thermal modelling, and bridge-specific structural knowledge to discriminate benign thermal expansion from damage-induced displacements and generate early-warning indicators for girder bridges.

- SAR-derived measurements capture only the absolute displacement of the entire structure along the satellite’s LOS, rendering it insensitive to relative internal deformations.

- The spatial resolution and temporal revisit frequency of current satellite constellations are often insufficient to resolve rapid or highly localised deformations.

- Signal quality and target identification present further challenges for the sparse distribution and low density of detectable coherent targets on bridge structures.

- Temporal and spatial decorrelation significantly reduce measurement coherence, especially for non-metallic, vegetated, or geometrically complex bridges.

- There is a lack of standardised, automated, and interoperable frameworks capable of bridging the gap between geodetic observations and engineering decision-making.

- There is a difficulty in translating geodetic observations into actionable engineering insights.

- There is a persistent difficulty in distinguishing genuine structural deformations from environmental effects, particularly thermal expansion.

- There is a lack of integration with mechanical behaviour models or component-specific deformation thresholds.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, M.Q.; Sousa, H.S.; Ngo, T.V.; Nguyen, B.D.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, H.X.; Baron, E.; Matos, J.; Dang, S.N. Structural Assessment Based on Vibration Measurement Test Combined with an Artificial Neural Network for the Steel Truss Bridge. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Rakoczy, A.M.; Cabral, R.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y.; Santos, R.; Tondo, G.; Gonzalez, L.; Matos, J.C.; Futai, M.M.; et al. Methodologies for Remote Bridge Inspection—Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.; Van, T.N.; Nguyen, H.X.; Nguyễn, Q. Enhancing the Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) through data reconstruction: Integrating 1D convolutional neural networks (1DCNN) with bidirectional long short-term memory networks (Bi-LSTM). Eng. Struct. 2025, 340, 120767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Au, F.T. SAR-Transformer-based decomposition and geophysical interpretation of InSAR time-series deformations for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 302, 113962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiarulo, V.; Milillo, P.; Blenkinsopp, C.; Giardina, G. Monitoring deformations of infrastructure networks: A fully automated GIS integration and analysis of InSAR time-series. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 1849–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettis, A.; Massimi, V.; Nutricato, R.; Nitti, D.O.; Samarelli, S.; Uva, G. Satellite-based interferometry for monitoring structural deformations of bridge portfolios. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markogiannaki, O.; Xu, H.; Chen, F.; Mitoulis, S.A.; Parcharidis, I. Monitoring of a landmark bridge using SAR interferometry coupled with engineering data and forensics. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, V.; Tosti, F.; Ciampoli, L.B.; Battagliere, M.L.; D’amato, L.; Alani, A.M.; Benedetto, A. Satellite Remote Sensing and Non-Destructive Testing Methods for Transport Infrastructure Monitoring: Advances, Challenges and Perspectives. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O.; Cuevas-González, M.; Devanthéry, N.; Crippa, B. Persistent Scatterer Interferometry: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, M.; Dorninger, P.; Kwapisz, M.; Ralbovsky, M.; Spielhofer, R. Remote Sensing Techniques for Bridge Deformation Monitoring at Millimetric Scale: Investigating the Potential of Satellite Radar Interferometry, Airborne Laser Scanning and Ground-Based Mobile Laser Scanning. PFG–J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2022, 90, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, M.; Widhalm, B.; Avian, M. Comprehensive time-series analysis of bridge deformation using differential satellite radar interferometry based on Sentinel-1. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 172, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, D.; Caspani, V.F.; Valentini, A.; Rocca, A.; Torboli, R.; Vitti, A.; Perissin, D.; Zonta, D. Interpretation of Bridge Health Monitoring Data from Satellite InSAR Technology. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Wu, J.; Song, R.; Liang, H.; Bian, W. Toward Retrieving Discontinuous Deformation of Bridges by MTInSAR With Adaptive Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy, A.M.; Ribeiro, D.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y.; Olaszek, P.; Karwowski, W.; Cabral, R.; Guo, Y.; Futai, M.M.; Milillo, P.; et al. Technologies and Platforms for Remote and Autonomous Bridge Inspection–Review. Struct. Eng. Int. 2025, 35, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Acevedo, G.M.; Vazquez-Becerra, G.E.; Quintana-Rodriguez, J.A.; Gaxiola-Camacho, J.R.; Anaya-Diaz, M.; Mediano-Martinez, J.C.; Viramontes, F.J.C. Structural health monitoring and risk assessment of bridges integrating InSAR and a calibrated FE model. Structures 2024, 63, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, A.; Mele, A.; Silla, M.; Bonano, M.; Striano, P.; Lanari, R.; Di Ludovico, M.; Prota, A. Space-borne DInSAR measurements exploitation for risk classification of bridge networks. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 15, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farneti, E.; Cavalagli, N.; Venanzi, I.; Salvatore, W.; Ubertini, F. Residual service life prediction for bridges undergoing slow landslide-induced movements combining satellite radar interferometry and numerical collapse simulation. Eng. Struct. 2023, 293, 116628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Lei, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, L. Artificial Intelligence Based Structural Assessment for Regional Short- and Medium-Span Concrete Beam Bridges with Inspection Information. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumaran, S.; Rossi, C.; Marinoni, A.; Webb, G.; Bennetts, J.; Barton, E.; Plank, S.; Middleton, C. Combined InSAR and Terrestrial Structural Monitoring of Bridges. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 7141–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.; Turksezer, Z.; Previtali, M.; Limongelli, M. Damage detection on a historic iron bridge using satellite DInSAR data. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 2291–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezami, A.; Behkamal, B.; De Michele, C.; Mariani, S. Displacement prediction for long-span bridges via limited remote sensing images: An adaptive ensemble regression method. Measurement 2025, 245, 116567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusson, D.; Rossi, C.; Ozkan, I.F. Early warning system for the detection of unexpected bridge displacements from radar satellite data. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 11, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Luzi, G.; Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, H.; Ding, Y. Ground-Based Radar Interferometry for Monitoring the Dynamic Performance of a Multitrack Steel Truss High-Speed Railway Bridge. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hao, G.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.; Zheng, J. Long-term deformation monitoring of a steel-truss arch bridge using PSI technique refined by temperature field analysis. Eng. Struct. 2024, 311, 118164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, F.; Giannetti, I.; Romualdi, A.; Meda, A.; Rinaldi, Z. On the DInSAR technique for the structural monitoring of modern existing bridges. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Bridg. Eng. 2025, 178, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gao, K.; Wu, G.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, H. A deep learning-based interferometric synthetic aperture radar framework for abnormal displacement deformation prediction of bridges. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2023, 26, 3005–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farneti, E.; Cavalagli, N.; Costantini, M.; Trillo, F.; Minati, F.; Venanzi, I.; Ubertini, F. A method for structural monitoring of multispan bridges using satellite InSAR data with uncertainty quantification and its pre-collapse application to the Albiano-Magra Bridge in Italy. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Rashidi, M. A Novel Slip Sensory System for Interfacial Condition Monitoring of Steel-Concrete Composite Bridges. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, G.M.G.; Moreno, V.T.; Rodríguez, J.A.Q.; Becerra, G.E.V.; Zamora, H.M.G.; Trujano, L.Á.M.; Figueroa, J.A.H.; Viramontes, F.G.C.; Díaz, M.A.; López, A.G.P. Implementación de InSAR Para el Monitoreo Estructural de Puentes; Comunicaciones; Secretaría de Infraestructura, Comunicaciones Y Transportes: Querétaro, México, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Banic, M.; Ristic-Durrant, D.; Madic, M.; Klapper, A.; Trifunovic, M.; Simonovic, M.; Fischer, S. The Use of Earth Observation Data for Railway Infrastructure Monitoring—A Review. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, F.; Addabbo, P.; Ullo, S.L.; Clemente, C.; Orlando, D. Perspectives on the Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges by Synthetic Aperture Radar. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Mutz, R. Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Stemmler, C.; Wolf, N.; Koppe, M.; Rudolph, T.; Müterthies, A. Fusion of BIM and SAR for Innovative Monitoring of Urban Movement–Towards 4D Digital Twin. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-G-2, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarneving, B. A comparison of two bibliometric methods for mapping of the research front. Scientometrics 2005, 65, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, W. Using TerraSAR X-Band and Sentinel-1 C-Band SAR Interferometry for Deformation Along Beijing-Tianjin Intercity Railway Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4832–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Wright, T.; Hooper, A.; Selvakumaran, S. Using Ray Tracing to Improve Bridge Monitoring With High-Resolution SAR Satellite Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-Y. Urban hazards caused by ground deformation and building subsidence over fossil lake beds: A study from Taipei City. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2022, 13, 2890–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Dong, S.; Yin, H.; Ye, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H. Unravelling long-term spatiotemporal deformation and hydrological triggers of slow-moving reservoir landslides with multi-platform SAR data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 135, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, W.; Qin, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, G.; Zhu, M. Time-Series InSAR Deformation Monitoring of High Fill Characteristic Canal of South–North Water Diversion Project in China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, C.; Qin, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, Q. Time-Series Analysis on Persistent Scatter-Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (PS-InSAR) Derived Displacements of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge (HZMB) from Sentinel-1A Observations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, M.; Wu, Y.; Du, W. Three-dimensional surface deformation field monitoring and influencing factors analysis in mountainous areas based on SBAS-INSAR technology (Tianjin, China). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, R.; Petryna, Y.; Lubitz, C.; Lang, O.; Wegener, V. Thermal deformation monitoring of a highway bridge: Combined analysis of geodetic and satellite-based InSAR measurements with structural simulations. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 14, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Acevedo, G.M.; Quintana-Rodriguez, J.A.; Gaxiola-Camacho, J.R.; Vazquez-Becerra, G.E.; Torres-Moreno, V.; Monjardin-Quevedo, J.G. The Structural Reliability of the Usumacinta Bridge Using InSAR Time Series of Semi-Static Displacements. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cai, J.; Xiang, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, X. The Deformation Monitoring Capability of Fucheng-1 Time-Series InSAR. Sensors 2024, 24, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, G. Surface Deformation Time-Series Monitoring and Stability Analysis of Elevated Bridge Sites in a Coal Resource-Based City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Qian, Z.; Chen, B.; Yang, W.; Hao, P. Surface Deformation of Xiamen, China Measured by Time-Series InSAR. Sensors 2024, 24, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Z.; Qin, J.; Xian, L.; Zhang, D.; Huang, L. Surface Deformation Mechanism Analysis in Shanghai Areas Based on TS-InSAR Technology. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behkamal, B.; Entezami, A.; De Michele, C.; Arslan, A.N. Investigation of Temperature Effects into Long-Span Bridges via Hybrid Sensing and Supervised Regression Models. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, Z.; Du, Z. Investigating two-dimensional deformations of the head of the Central Route of the South–North Water Diversion Project in China with TerraSAR-X datasets. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2228457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Lombardo, L.; Chang, L.; Sadhasivam, N.; Hu, X.; Fang, Z.; Dahal, A.; Fadel, I.; Luo, G.; Tanyas, H. Investigating earthquake legacy effect on hillslope deformation using InSAR-derived time series. Earth Surf. Process Landf. 2024, 49, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögel, R.; Owczarz, K.; Orban, A.; Havenith, H.-B. Investigating Earth surface deformation with SAR interferometry and geomodeling in the transborder Meuse–Rhine region. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1366944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Gagliardi, V.; Bianchini Ciampoli, L.; Tosti, F. Integration of InSAR and GPR techniques for monitoring transition areas in railway bridges. NDT E Int. 2020, 115, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, E.; Orellana, F.; Arratia, C.; Tavasci, L.; Montalva, G.; Moreno, M.; Gandolfi, S. InSAR Monitoring Using Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) and Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) Techniques for Ground Deformation Measurement in Metropolitan Area of Concepción, Chile. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, M.; Dong, J.; Liao, M. Investigating deformation along metro lines in coastal cities considering different structures with InSAR and SBM analyses. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Li, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, J. Incorporating Physical Constraint in Three-Dimensional Time Series InSAR Inversion for Urban Deformation Monitoring. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 13967–13985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zimmer, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Ghuman, P.; Cheng, I. IGS-CMAES: A Two-Stage Optimization for Ground Deformation and DEM Error Estimation in Time Series InSAR Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemer, J.; Jänichen, J.; Stein, G.; Liedel, N.; Wicker, C.; Last, K.; Denzler, J.; Schmullius, C.; Shadaydeh, M.; Dubois, C. Identifying Deformation Drivers in Dam Segments Using Combined X- and C-Band PS Time Series. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, C.; Yan, B.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Li, W.; Yang, L. Hongtang Bridge Expansion Joints InSAR Deformation Monitoring with Advanced Phase Unwrapping and Mixed Total Least Squares in Fuzhou China. Sensors 2024, 25, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Zou, J.; Lu, Z.; Qu, F.; Kang, Y.; Li, J. Ground Deformation of Wuhan, China, Revealed by Multi-Temporal InSAR Analysis. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomibao, A.L.; Leal, G.A.; Mabaquiao, L.C.; Reyes, R.B. Ground Deformation Monitoring of Reclaimed Lands Along Manila Bay Freeport Zone Using Ps-Insar Technique. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-4/W8-2023, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, N.; Ding, X.; Wu, S.; Liang, H. Ground Deformation and Its Causes in Abbottabad City, Pakistan from Sentinel-1A Data and MT-InSAR. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, L.; Ma, J.; Shi, A.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. GB-RAR Deformation Information Estimation of High-Speed Railway Bridge in Consideration of the Effects of Colored Noise. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, R.; Scaioni, M. European Ground Motion Service for Bridge Monitoring: Temporal and Thermal Deformation Cross-Check Using Cosmo-Skymed Insar. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-1/W2-2023, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraj, K.; Chatterjee, R.S.; Shukla, D.P. Estimating the period of probable landslide event using advanced D-InSAR technique for time-series deformation study of Kotrupi region. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2281245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zuo, X.; Yang, F.; Bu, J.; Wu, W.; Liu, X. Effectiveness evaluation of DS-InSAR method fused PS points in surface deformation monitoring: A case study of Hongta District, Yuxi City, China. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2176011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y. Determining Suitable Spaceborne SAR Observations and Ground Control Points for Surface Deformation Study in Rugged Terrain With InSAR Technique. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 11324–11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Ke, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Guo, L.; Gong, H. Detection of Seasonal Deformation of Highway Overpasses Using the PS-InSAR Technique: A Case Study in Beijing Urban Area. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, G.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zeng, T. Deformation Monitoring of Truss Structure Bridge With Time-Series InSAR Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 1982–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, A.; Chen, Y. Deformation monitoring of long-span railway bridges based on SBAS-InSAR technology. Geod. Geodyn. 2024, 15, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Jin, X.; Nie, D.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y. Deformation Monitoring Based on SBAS-InSAR and Leveling Measurement: A Case Study of the Jing-Mi Diversion Canal in China. Sensors 2024, 24, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Ma, Q.; Qin, X.; Ao, M.; Li, X.; Zhao, D.; Tolomei, C. Deformation and Stress Status of a Cable-Stayed Bridge Revealed by Incorporating Ascending-Descending Time Series Interferometric SAR Fusion and Finite Element Modeling. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 13372–13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, Q.; Ding, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, C.; Liao, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, S. A structure knowledge-synthetic aperture radar interferometry integration method for high-precision deformation monitoring and risk identification of sea-crossing bridges. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 103, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumaran, S.; Sadeghi, Z.; Collings, M.; Rossi, C.; Wright, T.; Hooper, A. Comparison of in situ and interferometric synthetic aperture radar monitoring to assess bridge thermal expansion. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Smart Infrastruct. Constr. 2022, 175, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, R.; Reale, D.; Bonano, M.; Verde, S.; Muhammad, Y.; Fornaro, G.; Casu, F.; Manunta, M. Comment on “Pre-Collapse Space Geodetic Observations of Critical Infrastructure: The Morandi Bridge, Genoa, Italy” by Milillo et al. (2019). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Wassie, Y.; Navarro, J.A.; Palamà, R.; Krishnakumar, V.; Barra, A.; Cuevas-González, M.; Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O. Classification of ground deformation using sentinel-1 persistent scatterer interferometry time series. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Feng, W.; Masci, O.; Nico, G.; Alani, A.M.; Sato, M. Bridge Monitoring Strategies for Sustainable Development with Microwave Radar Interferometry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Shen, C.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, W. Bridge Deformation Prediction Using KCC-LSTM With InSAR Time Series Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 9582–9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xiao, W.; Zhu, H.; Ning, S.; Huang, S.; Jin, D.; A, R.; Thapa, B.R. Analysis of Uneven Settlement of Long-Span Bridge Foundations Based on SBAS-InSAR. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, A.M.; Tosti, F.; Bianchini Ciampoli, L.; Gagliardi, V.; Benedetto, A. An integrated investigative approach in health monitoring of masonry arch bridges using GPR and InSAR technologies. NDT E Int. 2020, 115, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buka-Vaivade, K.; Nicoletti, V.; Gara, F. Advancing bridge resilience: A review of monitoring technologies for flood-prone infrastructure. Open Res. Eur. 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calò, M.; Ruggieri, S.; Nettis, A.; Uva, G. A MTInSAR-Based Early Warning System to Appraise Deformations in Simply Supported Concrete Girder Bridges. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2024, 1, 8978782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, A.M.H.; Din, A.H.M.; Latip, A.S.A.; Reba, M.N.M. A Short Review on Persistent Scatterer Interferometry Techniques for Surface Deformation Monitoring. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, XLVI-4/W3-2021, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, W.; He, S. A Persistent Scatterer Point Selection Method for Deformation Monitoring of Under-Construction Cross-Sea Bridges Using Statistical Theory and GMM-EM Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xue, X.; Zhi, G.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, H. A Novel Monitoring Method of Wind-Induced Vibration and Stability of Long-Span Bridges Based on Permanent Scatterer Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Technology. Sensors 2025, 25, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talledo, D.A.; Saetta, A. A Multi-Level Semi-Automatic Procedure for the Monitoring of Bridges in Road Infrastructure Using MT-DInSAR Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Ma, S.; Shan, Q.; Jiang, W. Study on LOS to Vertical Deformation Conversion Model on Embankment Slopes Using Multi-Satellite SAR Interferometry. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farneti, E.; Meoni, A.; Natali, A.; Celati, S.; Frascella, C.; Lupi, M.C.; Cavalagli, N.; Venanzi, I.; Salvatore, W.; Ubertini, F. Structural Health Monitoring of Curved Roadway Bridges Through Satellite Radar Interferometry and Collapse Simulation. ce/papers 2023, 6, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Nico, G.; Alani, A.M.; Sato, M. Strategy for vertical deformation of railway bridge monitoring using polarimetric ground-based real aperture radar system. Struct. Healthy Monit. 2024, 23, 3719–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, S.; Wang, C.; Wu, S.; Zhu, W. Spatiotemporal-grained quantitative assessment of construction-induced deformation along the MTR in Hong Kong using MT-InSAR and iterative STL-based subsidence ratio analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 136, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, L.; Mondillo, N.; Rodas, R.A.; Sellers, C.; Di Martire, D. Monitoring Land Surface Deformation Associated with Gold Artisanal Mining in the Zaruma City (Ecuador). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, B. Slow Deformation Time-Series Monitoring for Urban Areas Based on the AWHPSPO Algorithm and TELM: A Case Study of Changsha, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusson, D.; Stewart, H. Satellite Synthetic Aperture Radar, Multispectral, and Infrared Imagery for Assessing Bridge Deformation and Structural Health—A Case Study at the Samuel de Champlain Bridge. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Li, W.; Li, G.; Kang, Y.; Zheng, S. SAR Interferometry Infrastructure Deformation Monitoring by the Number of Redundant Observations Optimizes Phase Unwrapping Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 7201–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Jiao, Z.; Wu, Z. Robust Time-Series InSAR Deformation Monitoring by Integrating Variational Mode Decomposition and Gated Recurrent Units. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3208–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, S.; Yu, H.; Wu, H.; Li, M. Revealing Urban Deformation Patterns through InSAR Time Series Analysis with TCN and Transfer Learning. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-1-2, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, C.; Huang, P.; Yin, B.; Tan, W.; Qi, Y.; Xu, W.; Du, S. Research on Time Series Monitoring of Surface Deformation in Tongliao Urban Area Based on SBAS-PS-DS-InSAR. Sensors 2024, 24, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milillo, P.; Giardina, G.; Perissin, D.; Milillo, G.; Coletta, A.; Terranova, C. Reply to Lanari, R.; et al. Comment on “Pre-Collapse Space Geodetic Observations of Critical Infrastructure: The Morandi Bridge, Genoa, Italy” by Milillo et al. (2019). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasri, O.; Giordano, P.F.; Limongelli, M.P.; Previtali, M. Remote monitoring of a concrete bridge using PSInSAR. ce/papers 2023, 6, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quqa, S.; Palermo, A.; Ubertini, F.; Marzani, A. Regional-scale bridge condition monitoring using InSAR displacements and environmental data. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 24, 2271–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quqa, S.; Lasri, O.; Delo, G.; Giordano, P.F.; Surace, C.; Marzani, A.; Limongelli, M.P. Regional-scale bridge health monitoring: Survey of current methods and roadmap for future opportunities under changing climate. Struct. Healthy Monit. 2025, 24, 2309–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramov, E.; Sydyk, N.; Nurakynov, S.; Yelisseyeva, A.; Neafie, J.; Aliyeva, S. Quantitative assessment of urban surface deformation risks from tectonic and seismic activities using multitemporal microwave satellite remote sensing: A case study of Almaty city and its surroundings in Kazakhstan. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1502403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, M.; Thiele, A.; Hammer, H.; Hinz, S. PSDefoPAT—Persistent Scatterer Deformation Pattern Analysis Tool. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Yu, X.; Tan, H.; Xie, S.; Yang, X.; Han, Y. Prediction Parameters for Mining Subsidence Based on Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Collaborative Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y. Prediction of surface deformation time series in closed mines based on LSTM and optimization algorithms. Open Geosci. 2025, 17, 20250811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talledo, D.A.; Miano, A.; Bonano, M.; Di Carlo, F.; Lanari, R.; Manunta, M.; Meda, A.; Mele, A.; Prota, A.; Saetta, A.; et al. Satellite radar interferometry: Potential and limitations for structural assessment and monitoring. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamvasis, K.; Karathanassi, V. Performance Analysis of Open Source Time Series InSAR Methods for Deformation Monitoring over a Broader Mining Region. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morga, M.; Calò, M.; Nettis, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Doglioni, A.; Simeone, V.; Uva, G. On the use of MTInSAR data and UAV photogrammetry to monitor the behaviour of existing bridge portfolios. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 62, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahli, A.; Simonetto, E.; Tatin, M.; Durand, S.; Morel, L.; Lamour, V. ON the Combination of Psinsar and Gnss Techniques for Long-Term Bridge Monitoring. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII-B3-2020, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, Z.; Balz, T.; Asghar, A. Non-Linear PSInSAR Analysis of Deformation Patterns in Islamabad/Rawalpindi Region: Unveiling Tectonics and Earthquake-Driven Changes. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukanská, K.; Bartoš, K.; Bakoň, M.; Papčo, J.; Kubica, L.; Barlák, J.; Rovňák, M.; Kseňak, Ľ.; Zelenakova, M.; Savchyn, I.; et al. Multi-sensor and multi-temporal approach in monitoring of deformation zone with permanent monitoring solution and management of environmental changes: A case study of Solotvyno salt mine, Ukraine. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1167672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lai, S.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liao, M. Multi-scale deformation monitoring with Sentinel-1 InSAR analyses along the Middle Route of the South-North Water Diversion Project in China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100, 102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calò, M.; Ruggieri, S.; Nettis, A.; Uva, G. Multi source Interferometry Synthetic Aperture Radar for monitoring existing bridges: A case study. ce/papers 2023, 6, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, H.; Eronat, A.H. Monitoring the Ground Deformation Caused by Ankara M4 Subway Tunnel with SAR Images. Int. J. Environ. Geoinform. 2023, 10, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, D.; Ma, C.; Lian, D. Monitoring Subsidence Deformation of Suzhou Subway Using InSAR Timeseries Analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 3400–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ellingsen, P.G. Monitoring of thermal deformation of cylindrical storage facilities with DInSAR. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 16, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausilio, G.; Khalili, M.A.; Virelli, M.; Di Martire, D. Italian COSMO-SkyMed atlas: R-Index and the percentage of measurability of movement. GIScience Remote Sens. 2024, 61, 2312705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Yan, B.; Cai, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, S. L2-Norm Quasi 3-D Phase Unwrapping Assisted Multitemporal InSAR Deformation Dynamic Monitoring for the Cross-Sea Bridge. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 18926–18938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Wei, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, D. Large-Scale Land Deformation Monitoring over Southern California with Multi-Path SAR Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Lee, C.; Kim, B.-K.; Kim, K.; Lee, I. Leveraging Multi-Temporal InSAR Technique for Long-Term Structural Behaviour Monitoring of High-Speed Railway Bridges. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasri, O.; Giordano, P.F.; Limongelli, M.P. Remote Structural Health Monitoring of Concrete Bridge Using InSAR: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring: Designing SHM for Sustainability, Maintainability, and Reliability, IWSHM 2023, Stanford, CA, USA, 12–14 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Zhong, Y.; Li, H.; Al-Masnay, Y.A.; Haq, I.U.; Khan, M.; Faheem, H.; Ali, R. Integration of Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar and Persistent Scatterer Interferometric Approaches to Assess Deformation in Enshi City, Hubei, China. Front Earth Sci. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciulli, C.; Guiduzzi, G.; Tiano, D.; Zocchi, M.; Guerra, F.; Mazzanti, P.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G. Interpretable Clustering of PS-InSAR Time Series for Ground Deformation Detection. Comput. Geosci. 2025, 203, 105959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicioglu, K.; Erten, E.; Rossi, C. Monitoring deformations of Istanbul metro line stations through Sentinel-1 and levelling observations. Environ Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Hou, J.; Wang, Q. Monitoring Bridge Vibrations Based on GBSAR and Validation by High-Rate GPS Measurements. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 5572–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Peng, J. Monitoring and Stability Analysis of the Deformation in the Woda Landslide Area in Tibet, China by the DS-InSAR Method. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ding, X.; Wu, S.; Fu, H.; Zhu, J. Mitigation of Atmospheric Effects in Deformation Monitoring Using Dual-Polarization MTInSAR and Improved Wavelet Correlation Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 5704–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liao, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, S.; Wang, C.; Wu, S.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, J.; Qin, X.; Li, Q. Megalopolitan-Scale Ground Deformation along Metro Lines in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China, Revealed by MT-InSAR. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 122, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Jiang, X. Mapping Vertical and Horizonal Deformation of the Newly Reclaimed Third Runway at Hong Kong International Airport with PAZ, COSMO-SkyMed, and Sentinel-1 SAR Images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.B.; Salah, M.; Zarzoura, F.H.F.; El-Mewafi, M. Mapping of Surface Deformation Associated with the 7.8 Magnitude Turkey Earthquake of 6 Feb 2023 Using Radar Interferometry. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumalawati, R.; Ali, S.D.; Yuliarti, A.; Raharjo, J.T.; Rijanta, R.; Saputra, E.; Susanti, A.; Budiman, P.W.; Anggraini, R.N. Mapping of Land Surface Deformation Using Ps-Insar for Disaster Risk Management in the Future. J. Geogr. 2024, 16, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzis, P.; Mouratidis, A.; Vladenidis, P.; Ampatzidis, D.; Moshopoulos, G.; Domakinis, C.; Pantazopoulou, Z.; Karadimou, G.; Perivolioti, T.-M.; Terzopoulos, D.; et al. Mapping and Monitoring Subtle Ground Deformation in Sindos, Greece, with High Precision Digital Leveling. Auc Geogr. 2023, 58, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Q.; Gui, R.; Hu, J.; Yang, Q.; Su, G. Long-Time Surface Deformation in Beijing, China for Three Decades by Multi-Sensor, Multi-Track and Multi-Temporal InSAR Seamless Connection. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2025, 16, 2478950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.; Lee, S.-R.; Kwon, T.-H. Long-Term Remote Monitoring of Ground Deformation Using Sentinel-1 Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR): Applications and Insights into Geotechnical Engineering Practices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.F.; Kwapisz, M.; Miano, A.; Liuzzo, R.; Vorwagner, A.; Limongelli, M.P.; Prota, A.; Ralbovsky, M. Monitoring of a Multi-span Prestressed Concrete Bridge Using Satellite Interferometric Data and Comparison with On-site Sensor Results. Struct. Concr. 2025, 26, 5430–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Yun, H.-S.; Kim, T.-Y. Monitoring of High-Speed Railway Ground Deformation Using Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, A.; Ahmed, M.; Chu, T.; Gebremichael, E.; Elshalkany, M.; Abdelrehim, R. Temporal Gravimetry, Campaign and Permanent GNSS, and Interferometric Radar Techniques: A Comparative Approach to Quantifying Land Deformation Rates in Coastal Texas. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.; Saralioglu, E.; Turab, S.A.; Muhammad, S. Tracking Surface and Subsurface Deformation Associated with Groundwater Dynamics Following the 2019 Mirpur Earthquake. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2195966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chen, B.; Na, J.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Du, X. Urban Surface Deformation Management: Assessing Dangerous Subsidence Areas through Regional Surface Deformation, Natural Factors, and Human Activities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Miele, P.; Petti, L.; Guida, D.; Guadagno, F.M.; Moschillo, R.; Vicari, A. What Have We Learned from the Past? An Analysis of Ground Deformations in Urban Areas of Palermo (Sicily, Italy) by Means of Multi-Temporal Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry Techniques. Geosciences 2023, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; He, M. Multi-scale deformation monitoring and characterization of large-span railway bridge by joint satellite/ground-based InSAR and BDS. Measurement 2025, 256, 118199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.F.; Kamariotis, A.; Giardina, G.; Chatzi, E.; Limongelli, M.P. Uncertainty propagation in satellite InSAR data analysis for structural health monitoring. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calò, M.; Ruggieri, S.; Doglioni, A.; Morga, M.; Nettis, A.; Simeone, V.; Uva, G. Probabilistic-based assessment of subsidence phenomena on the existing built heritage by combining MTInSAR data and UAV photogrammetry. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, S.; Shi, G.; Ding, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Lu, Z. Mapping ground deformation in the northern Yangtze River estuary using improved MT-InSAR based on ICA and non-stationary analysis. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 2380–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Keyword Groups | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 | displacement | |

| monitoring | Cosmo Sky Med | deformation | ||

| interferometry multi-temporal persistent Scatterer | ||||

| digital twin |

| Keyword Group 1 | Keyword Group 2 | Keyword Group 3 | Keyword Group 4 | Records Scopus | Records WoS | Records Dimensions | Total Records | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bridge | SAR | 18,107 | 1651 | 399,938 | 419,696 | ||

| 2 | Bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 | 1784 | 74 | 35,154 | 37,012 | |

| 3 | Bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | 1785 | 62 | 8246 | 10,093 | |

| 4 | Bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | displacement OR deformation | 999 | 24 | 9788 | 10,811 |

| 5 | Bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | Interferometry OR multi-temporal OR persistent scatterer | 690 | 18 | 1201 | 1909 |

| 6 | Bridge | SAR | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | digital twin | 76 | 0 | 2945 | 3021 |

| 7 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | 5809 | 274 | 253,575 | 259,658 | ||

| 8 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | Sentinel 1 | 1543 | 36 | 31,975 | 33,554 | |

| 9 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | 1583 | 58 | 8493 | 10,134 | |

| 10 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | displacement OR deformation | 958 | 36 | 8493 | 9487 |

| 11 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | Interferometry OR multi-temporal OR persistent scatterer | 681 | 37 | 1179 | 1897 |

| 12 | Bridge | SAR, monitoring | Sentinel 1 OR COSMO-SkyMed | digital twin | 72 | 0 | 2903 | 2975 |

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | 84 | 98 | 126 | 133 | 146 | 125 | 712 |

| WoS | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Scopus | 44 | 85 | 89 | 95 | 97 | 89 | 499 |

| Dimensions | WoS | Scopus | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial scanning | 712 | 7 | 499 | 1218 |

| Records excluded by topic relations | −548 | −3 | −422 | |

| More relevant documents | 164 | 4 | 77 | 245 |

| Records excluded by citations | −58 | 0 | −59 | |

| Citation document inclusions | 107 | 4 | 18 | 129 |

| Feature | Dimensions | WoS | Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final timespan | 2020–2025 | 2022–2025 | 2020–2025 |

| Sources inside the database | 30 | 4 | 13 |

| Documents | 107 | 4 | 18 |

| Authors | 550 | 17 | 109 |

| Co-Authors per Doc | 4.5 | 3.25 | 5.06 |

| Author keywords | 553 | 42 | 440 |

| Citations | 1803 | 199 | 476 |

| Journals | Records | SJR-2024 | H-INDEX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote Sensing | 32 | 1.019 | Q1 | 217 |

| IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing | 10 | 1.349 | Q1 | 139 |

| Geomatics Natural Hazards and Risk | 6 | 1.053 | Q1 | 66 |

| International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation | 6 | 2.241 | Q1 | 144 |

| Applied Sciences | 5 | 0.521 | Q2 | 162 |

| Sensors | 5 | 0.764 | Q2 | 273 |

| Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring | 4 | 1.065 | Q1 | 49 |

| IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing | 4 | 2.397 | Q1 | 324 |

| Structural Health Monitoring | 4 | 1.394 | Q1 | 101 |

| Structural Control and Health Monitoring | 3 | 1.394 | Q1 | 101 |

| Others | 50 | |||

| Categories | Reference | Citation | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monitoring deformations of infrastructure networks: A fully automated GIS integration and analysis of InSAR time-series | Macchiarulo et al. [5] | 80 | 2022–2023 |

| 2 | Satellite radar interferometry: Potential and limitations for structural assessment and monitoring | Talledo et al. [105] | 77 | 2022 |

| 3 | Satellite Remote Sensing and Non-Destructive Testing Methods for Transport Infrastructure Monitoring: Advances, Challenges and Perspectives | Gagliardi et al. [8] | 77 | 2023 |

| 4 | Combined InSAR and Terrestrial Structural Monitoring of Bridges | Selvakumaran et al. [19] | 72 | 2020 |

| 5 | Comprehensive time-series analysis of bridge deformation using differential satellite radar interferometry based on Sentinel-1 | Schlögl et al. [11] | 65 | 2021 |

| 6 | Early warning system for the detection of unexpected bridge displacements from radar satellite data | Cusson et al. [22] | 62 | 2021 |

| 7 | Hongtang Bridge Expansion Joints InSAR Deformation Monitoring with Advanced Phase Unwrapping and Mixed Total Least Squares in Fuzhou China | Wang et al. [58] | 61 | 2024 |

| 8 | A method for structural monitoring of multispan bridges using satellite InSAR data with uncertainty quantification and its pre-collapse application to the Albiano-Magra Bridge in Italy | Ferneti et al. [27] | 54 | 2023 |

| 9 | Satellite-based interferometry for monitoring structural deformations of bridge portfolios | Nettis et al. [6] | 49 | 2023 |

| 10 | Damage detection on a historic iron bridge using satellite DInSAR data | Giordano et al. [20] | 44 | 2022 |

| 11 | SAR-Transformer-based decomposition and geophysical interpretation of InSAR time-series deformations for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge | Ma et al. [4] | 43 | 2024 |

| 12 | A structure knowledge-synthetic aperture radar interferometry integration method for high-precision deformation monitoring and risk identification of sea-crossing bridges | Qin et al. [72] | 42 | 2021 |

| 13 | Perspectives on the Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges by Synthetic Aperture Radar | Biondi et al. [31] | 37 | 2020 |

| 14 | A MTInSAR-Based Early Warning System to Appraise Deformations in Simply Supported Concrete Girder Bridges | Calò et al. [81] | 33 | 2024 |

| 15 | Ground-based radar interferometry for monitoring the dynamic performance of a multitrack steel truss high-speed railway bridge | Huang et al. [23] | 32 | 2020 |

| 16 | Interpretation of Bridge Health Monitoring Data from Satellite InSAR Technology | Tonelli et al. [12] | 30 | 2023 |

| 17 | Monitoring of a landmark bridge using SAR interferometry coupled with engineering data and forensics | Markogiannaki et al. [7] | 25 | 2022 |

| 18 | Investigation of Temperature Effects into Long-Span Bridges via Hybrid Sensing and Supervised Regression Models | Behkamal et al. [48] | 23 | 2023 |

| 19 | Performance Analysis of Open-Source Time Series InSAR Methods for Deformation Monitoring over a Broader Mining Region | Karamvasis & Karathanassi) [106] | 20 | 2020 |

| 20 | Reply to Lanari, R., et al. Comment on “Pre-Collapse Space Geodetic Observations of Critical Infrastructure: The Morandi Bridge, Genoa, Italy” | Milillo et al. [97] | 20 | 2020 |

| 21 | Remote Sensing Techniques for Bridge Deformation Monitoring at Millimetric Scale: Investigating the Potential of Satellite Radar Interferometry, Airborne Laser Scanning, and Ground-Based Mobile Laser Scanning | Schlögl et al. [10] | 17 | 2022 |

| Categories | Auhor | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | The Use of Earth Observation Data for Railway Infrastructure Monitoring—A Review | Banic et al. [30] | 2025 |

| 23 | Multi-scale deformation monitoring and characterisation of large-span railway bridge by joint satellite/ground-based InSAR and BDS | Li et al. [140] | 2025 |

| 24 | Remote Structural Health Monitoring of Concrete Bridge Using InSAR: A Case Study | Lasri et al. [120] | 2023 |

| 25 | Fusion of BIM and SAR for Innovative Monitoring of Urban Movement—Towards 4D Digital Twin | Yang et al. [33] | 2025 |

| Author | Year | Publications (H) | Years (n) | M-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schlögl, Matthias | 2021 | 2 (Q2,Q2) | 3 | 0.67 |

| Nettis, Andrea | 2024 | 2 (Q1,Q2) | 1 | 2.00 |

| Uva, Giuseppina | 2024 | 2 (Q1,Q2) | 1 | 2.00 |

| Category | Technique/Framework | Contribution to Bridge SHM |

|---|---|---|

| Validation | ATS, BDS/GNSS | High-precision reference displacement and dynamic validation |

| Target enhancement | Corner Reflectors | Stable, high-coherence PS on critical structural components |

| Subsurface diagnosis | NDT, GPR | Correlation between surface deformation and internal damage |

| Dynamic monitoring | GB-InSAR | High-frequency response under operational loads |

| Geometry and localization | LiDAR, ALS/MLS, UAV | High-resolution component mapping |

| Decision support | GIS, SABRI | Network-level screening and inspection prioritisation |

| Anomaly detection | SAND, ESMD | Separation of environmental and damage-induced deformation |

| Semantic integration | BIM, Digital Twins | Component-level interpretation and asset management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buelvas Moya, H.A.; Tran, M.Q.; Pereira, S.; Matos, J.C.; Dang, S.N. A Systematic Review of the Practical Applications of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Bridge Structural Monitoring. Sustainability 2026, 18, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010514

Buelvas Moya HA, Tran MQ, Pereira S, Matos JC, Dang SN. A Systematic Review of the Practical Applications of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Bridge Structural Monitoring. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010514

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuelvas Moya, Homer Armando, Minh Q. Tran, Sergio Pereira, José C. Matos, and Son N. Dang. 2026. "A Systematic Review of the Practical Applications of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Bridge Structural Monitoring" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010514

APA StyleBuelvas Moya, H. A., Tran, M. Q., Pereira, S., Matos, J. C., & Dang, S. N. (2026). A Systematic Review of the Practical Applications of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Bridge Structural Monitoring. Sustainability, 18(1), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010514