Application of Vis–NIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning for Assessing Soil Organic Carbon in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

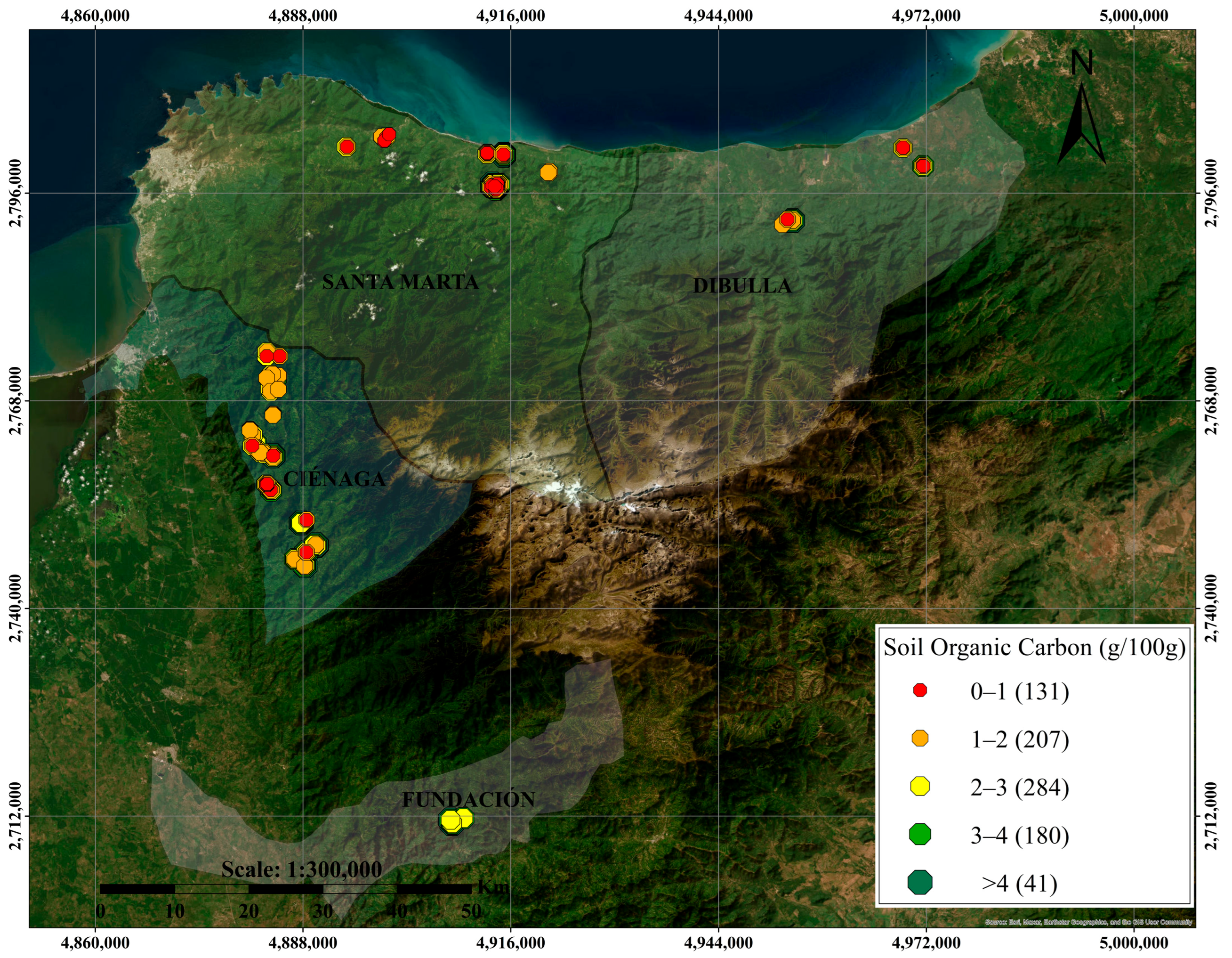

2.1.1. Study Area and Sample Collection Procedure

2.1.2. Chemical Measurements

2.1.3. Spectroscopy Vis–NIR

2.2. Methods

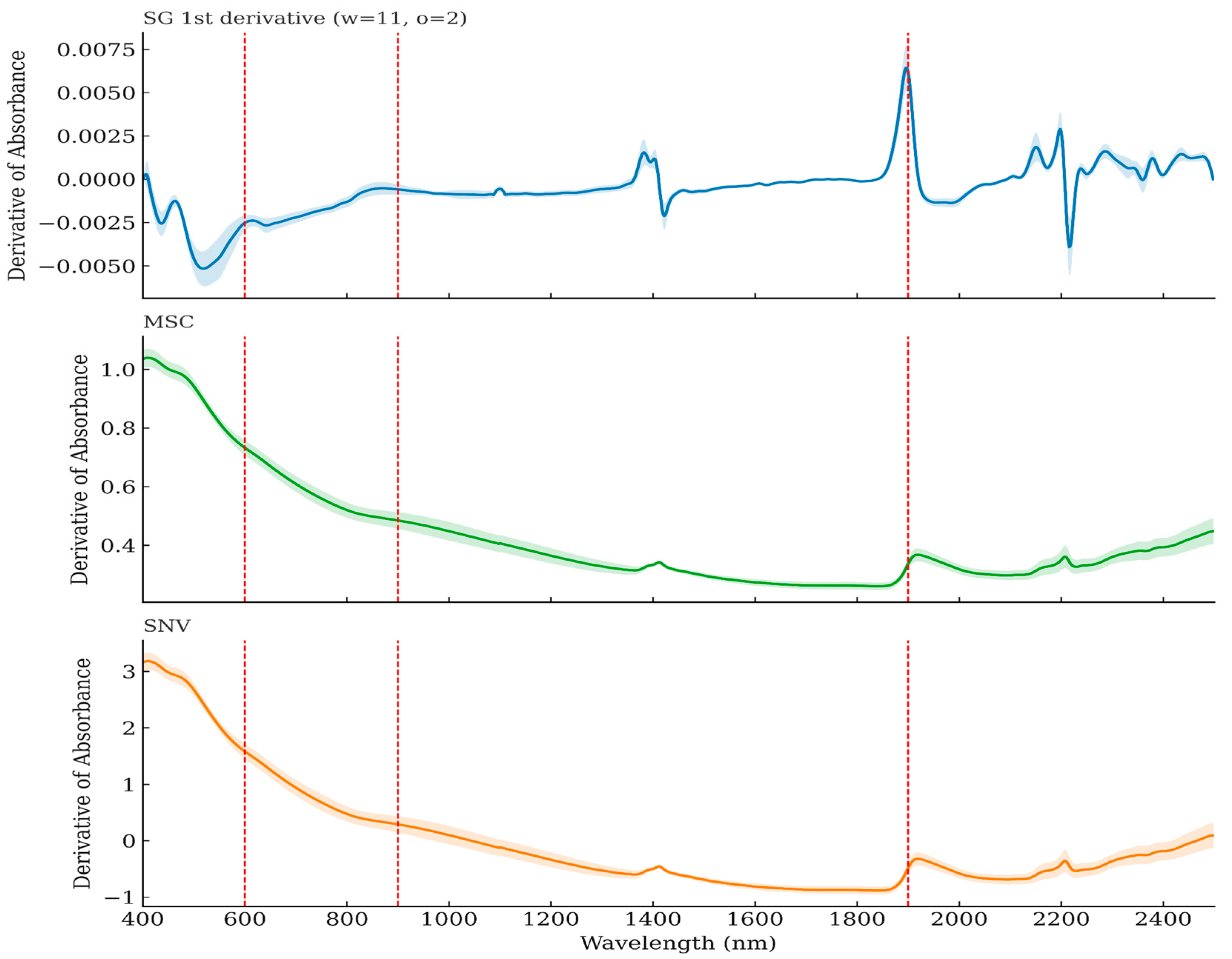

2.2.1. Preprocessing

2.2.2. Training Models

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Selected Soil Properties

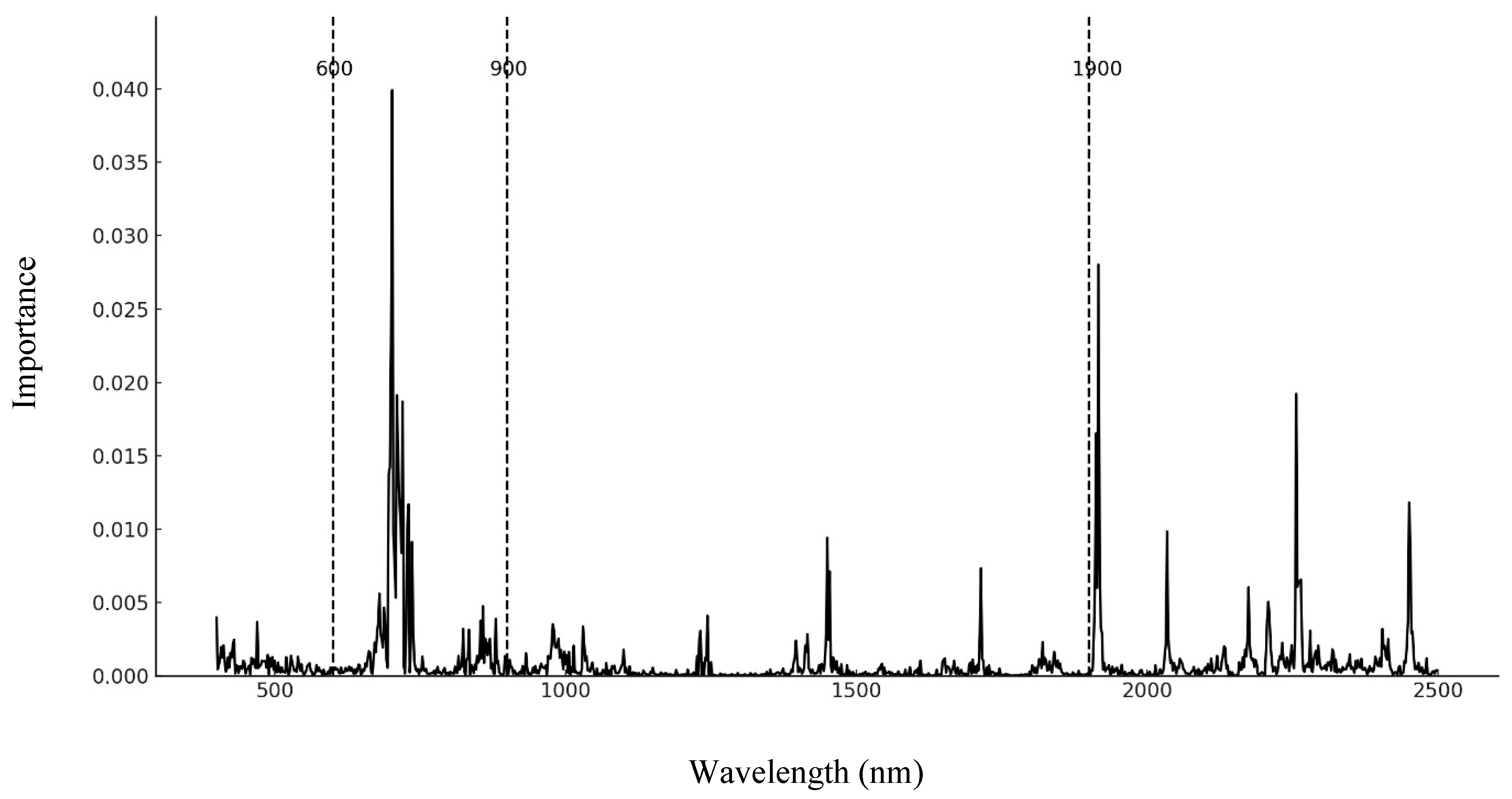

3.2. Data Processing

3.3. Selecting the Number of Trees and Characteristics per Node in a Random Forest Model

3.4. Model Selection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FCM | Fuzzy C-means |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| LIBS | Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy |

| MIR | Mid-Infrared |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MSC | Multiplicative Scatter Correction |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PCR | Principal Component Regression |

| PI | Prediction Interval |

| PLSR | Partial Least Squares Regression |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RF–SVR | Random Forest–Support Vector Regression |

| RF–XGBoost | Random Forest–Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| ROC | Readily Oxidizable Carbon |

| RPD | Residual Prediction Deviation |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SAFC | Agroforestry–Cacao Systems |

| SG | Savitzky–Golay |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| UL | Unsupervised Learning |

| Vis–NIR | Visible–Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Gerke, J. The central role of soil organic matter in soil fertility and carbon storage. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liang, Z. Organic carbon accumulation and aggregate formation in intensively managed soils. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Chang, X.; Huang, B.; Nie, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Jiang, J. The mineralization and sequestration of organic carbon in relation to agricultural soil erosion. Geoderma 2018, 329, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houba, V.J.G.; Novozamsky, I.; van der Lee, J.J. Quality aspects in laboratories for soil and plant analysis. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1996, 27, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, R.J.; Miller, P.C.H. A review of the technologies for mapping within-field variability. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 84, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetterl, S.; Six, J.; Van Wesemael, B.; Van Oost, K. Carbon cycling in eroding landscapes: Geomorphic controls on soil organic C pool composition and stability. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 18, 2218–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamifar, M.; Tavakoli, H.; Thiessen, E.; Kock, R.; Correa, J.; Hartung, E. Effective spectral pre-processing methods enhance accuracy of soil property prediction by NIR spectroscopy. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyi, K.E.; Shilin, R.E.; Liang, Y.I. Advancing soil property prediction with encoder-decoder structures integrating traditional deep learning methods in Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Geoderma 2024, 449, 117006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangeci, A.; Adén, D.; Nikolajsen, T.; Greve, M.H.; Knadel, M. Combining laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy and visible near-infrared spectroscopy for predicting soil organic carbon and texture: A Danish national-scale study. Sensors 2024, 24, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Pereira, S.; Araújo de França, C.; dos Santos, D.; Feliciano, R.; Menezes, R.; Simas, E.; Pereira, R. On the feasibility of Vis–NIR spectroscopy and machine learning for real-time SARS-CoV-2 detection. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 308, 123735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinilin, A.V.; Vindeker, G.V.; Savin, I.Y. Vis-NIR spectroscopy for soil organic carbon assessment: A meta-analysis. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvero, N.E.; Demattê, J.A.; Minasny, B.; Rosin, N.A.; Nascimento, J.G.; Albarracín, H.S.R.; Gómez, A.M. Sensing technologies for characterizing and monitoring soil functions: A review. Adv. Agron. 2023, 177, 125–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Duran, D.; Vargas-García, C.; Varón-Ramírez, V.; Calderón, F.; Montenegro, A.; Reyes-Herrera, P. Vis-NIR spectroscopy and machine learning methods to diagnose chemical properties in Colombian sugarcane soils. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 31, e00588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padarian, J.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Using deep learning to predict soil properties from regional spectral data. Geoderma Reg. 2019, 16, e00198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adab, H.; Morbidelli, R.; Saltalippi, C.; Moradian, M.; Ghalhari, G.A.F. Machine Learning to Estimate Surface Soil Moisture from Remote Sensing Data. Water 2020, 12, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.K.; Lee, S.J.; Park, J.H. Prediction of soil properties using vis-nir spectroscopy combined with machine learning: A review. Sensors 2025, 25, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohland, M.; Ludwig, B. Using variable selection and wavelets to exploit the full potential of visible–near infrared spectra for predicting soil properties. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2016, 24, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Shi, Z. Effectiveness of different approaches for in situ measurements of organic carbon using visible and near-infrared spectrometry in the Poyang Lake Basin area. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, A.K.; Wolff, S.B.E.; Ko, R.; Ölveczky, B.P. The basal ganglia control the detailed kinematics of learned motor skills. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shen, X.; Shen, X.; Cheng, J.; Xu, D.; Makar, R.S.; Guo, Y.; Hu, B.; Chen, S.; Hong, Y.; et al. Improving the Accuracy of Soil Classification by Using Vis–NIR, MIR, and Their Spectra Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.R.; Das, B.; Gaikwad, B.; Murgaonkar, D.; Desai, A.; Morajkar, S.; Patel, K.; Kulkarni, R. Monitoring properties of the salt-affected soils by multivariate analysis of the visible and near-infrared hyperspectral data. Catena 2021, 198, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.G.; Teixeira, A.D.S.; de Oliveira, M.R.R.; Costa, M.C.G.; Araújo, I.C.D.S.; Moreira, L.C.J.; Lopes, F.B. Soil organic carbon content prediction using soil-reflected spectra: A comparison of two regression methods. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.; Saffaj, T.; Ilham, B.; Saidi, O.; Issam, K.; Brahim, L.; El Hadrami, E.M. A comparative study between a new method and other machine learning algorithms for soil organic carbon and total nitrogen prediction using near-infrared spectroscopy. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2019, 195, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, C.; Yuan, J.; Ding, N.; Chen, Z. Prediction of soil properties based on characteristic wavelengths with optimal spectral resolution by using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 293, 122452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santana, F.; de Souza, A.; Poppi, R. Green methodology for soil organic matter analysis using a national near infrared spectral library in tandem with learning machine. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A.; Saberioon, M.; Borůvka, L.; Vašát, R. Soil organic carbon and texture prediction using visible and near-infrared spectroscopy and support vector machine regression: A case study from Czech agricultural soils. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, S.; Mouazen, A.M. On-line vis-NIR spectroscopy prediction of soil organic carbon using machine learning. Soil. Tillage Res. 2019, 190, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morellos, A.; Pantazi, X.-E.; Moshou, D.; Alexandridis, T.; Whetton, R.; Tziotzios, G.; Wiebensohn, J.; Bill, R.; Mouazen, A.M. Machine learning-based prediction of soil total nitrogen, organic carbon and moisture content using VIS-NIR spectroscopy. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 152, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, S.; Mouazen, A.M. Comparison between Random Forests, Artificial Neural Networks and Gradient Boosted Machines Methods of On-Line Vis-NIR Spectroscopy Measurements of Soil Total Nitrogen and Total Carbon. Sensors 2017, 17, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xu, D.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Shi, Z. Evaluation of machine learning approaches to predict soil organic matter and pH using vis-NIR spectra. Sensors 2019, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). Estudio General de Suelos y Zonificación de Tierras: Departamento de Magdalena, Escala 1:100000; Imprenta Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. Available online: https://catalogo.fedepalma.org/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=27933 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Six, J.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for soil C-saturation. Plant Soil. 2002, 241, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land use change on soil organic carbon stocks—A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Roose, E.; Feller, C. Soil Erosion and Carbon Dynamics; Roose, E.E.J., Meybeck, M., Lal, R., Feller, C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A. A critical examination of a rapid method for determining organic carbon in soils: Effect of variations in digestion conditions and of inorganic soil constituents. Soil Sci. 1947, 63, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlček, V.; Juřička, D.; Valtera, M.; Dvořáčková, H.; Štulc, V.; Bednaříková, M.; Šimečková, J.; Váczi, P.; Pohanka, M.; Kapler, P.; et al. Soil organic matter interactions along the elevation gradient of the Monte Baldo (Eastern Italian Alps). Soil 2024, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 1996, 3—Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, B.A. Methods for the Determination of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) in Soils and Sediments; EPA/600/R-02/069; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- FAO. Walkley–Black Method for Soil Organic Carbon Determination: Training Material; Global Soil Laboratory Network (GLOSOLAN): Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AGROSAVIA. Corporate Agenda Management—Sample Pretreatment for Soil Analysis (Code: GA-R-104); AGROSAVIA: Tolima, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Canero, F.M.; Rodríguez Galiano, V.; Aragón, D. Machine learning and feature selection for soil spectroscopy: An evaluation of Random Forest wrappers to predict soil organic matter, clay, and carbonates. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.H.; Morita, H.; Bachofer, F.; Ho, T.H. Random forest regression kriging modeling for soil organic carbon density estimation using multi-source environmental data in central Vietnamese forests. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 7137–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Arshad, M.; Wang, J.; Triantafilis, J. Soil exchangeable cations estimation using Vis-NIR spectroscopy in different depths: Effects of multiple calibration models and spiking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 182, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilash, P.; Hameed, M.A. Improvement of Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm using neural decision trees on miscarriage dataset. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing & Communication (ICICC 2024), New Delhi, India, 16–17 February 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.; Ramirez-Lopez, L. An Introduction to the Prospectr Package. 2015. Available online: https://mran.microsoft.com/snapshot/2017-08-06/web/packages/prospectr/vignettes/prospectr-intro.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- O’Haver, T.C. An introduction to signal processing in chemical measurement. J. Chem. Educ. 1991, 68, A147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudorff, C.M.; Novo, E.M.L.M.; Galvão, L.S.; Pereira Filho, W. Análise derivativa de dados hiperespectrais medidos em nível de campo e orbital para caracterizar a composição de águas opticamente complexas na Amazônia. Acta Amaz. 2007, 37, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocita, M.; Stevens, A.; Toth, G. Prediction of soil organic carbon content by diffuse reflectance spectroscopy using a local partial least square regression approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, B. Effects of soil sample pretreatments and standardised rewetting as interacted with sand classes on Vis-NIR predictions of clay and soil organic carbon. Geoderma 2010, 158, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura-Bueno, J.M.; Dalmolin, R.S.D.; ten Caten, A.; Oliveira, J.P.; Barros, F.M. Stratification of a local VIS-NIR-SWIR spectral library by homogeneity criteria yields more accurate soil organic carbon predictions. Geoderma 2019, 337, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, I.; Haefele, S.M.; Sakrabani, R.; Kebede, F. Soil spectroscopy with the use of chemometrics, machine learning and pre-processing techniques in soil diagnosis: Recent advances—A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 135, 116166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, A.C.; Dalmolin, R.S.D.; ten Caten, A.; Grunwald, S. A systematic study on the application of scatter-corrective and spectral-derivative preprocessing for multivariate prediction of soil organic carbon by Vis-NIR spectra. Geoderma 2018, 314, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milos, M.; Bensa, A. Organic carbon estimation in a regional soil Vis-NIR database supported by unsupervised learning and chemometrics techniquesr. Soil Adv. 2024, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Soil Spectroscopy: Apractical Guide for Measuring Soil Properties Using Reflectance Spectroscopy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasizadeh, H.; Maca, P.; Hanel, M.; Troldborg, M.; AghaKouchak, A. Can causal discovery lead to a more robust prediction model for runoff signatures? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 4761–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Linderman, M.; Mouazen, A.M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; et al. Comparing laboratory and airborne hyperspectral data for the estimation and mapping of topsoil organic carbon: Feature selection coupled with random forest. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z. Prediction of soil organic matter using different soil classification hierarchical level stratification strategies and spectral characteristic parameters. Geoderma 2022, 411, 115696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, B.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A. Visible and near-infrared spectroscopy in soil science. In Advances in Agronomy; Donald, L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasbian, I.; Xu, Z.; Boyd, S.; Zhou, J.; Esmaeilani, R.; Che, R.; Hosseini, B.S. Laboratory-based hyperspectral image analysis for predicting soil carbon, nitrogen and their isotope compositions. Geoderma 2018, 330, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloš, B.; Bensa, A. Prediction of soil organic carbon using VIS-NIR spectroscopy: Application to Red Mediterranean soils from Croatia. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2017, 6, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.M.H.; Coelho, A.P.; Fernandes, C.; da Silva, M.F.; Dela Marta, C.C. Estimation of soil organic matter content by modeling with artificial neural networks. Geoderma 2019, 350, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D.; de Dios Herrero, J.M.; Kloster, N. Uso de la espectroscopia visible e infrarrojo cercano para estimar propiedades de suelo en argentina. Cienc. Del. Suelo 2024, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Guo, B.; Zhuo, R.; Dai, F. Estimation of soil organic carbon in LUCAS soil database using Vis-NIR spectroscopy based on hybrid kernel Gaussian process regression. Spectrochim. Acta Part. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 310, 124687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudjihartono, N.; Fadason, T.; Kempa-Liehr, A.W.; O’Sullivan, J.M. A Review of Feature Selection Methods for Machine Learning-Based Disease Risk Prediction. Front. Bioinform. 2022, 2, 927312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, X.; Ma, X. Improving the Accuracy of Soil Organic Carbon Estimation: CWT-Random Frog-XGBoost as a prerequisite technique for in situ hyperspectral analysis. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Nie, L.; Cui, L.; Li, H.; Xiong, M.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, W. Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content. Ecologies 2025, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, A.R.S.; Alcibahy, M.; Gafoor, F.A.; Al Hashemi, H.; Athamneh, B.; Al Hammadi, A.A.; Seneviratne, L.; Al Shehhi, M.R. Estimation of soil organic carbon in arid agricultural fields based on hyperspectral satellite images. Geoderma 2024, 453, 117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Farms | Average (g 100 g−1) | Error | SD (g 100 g−1) | CV (%) | Min (g 100 g−1) | Max (g 100 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altamira | 1.57 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 8.11 | 1.48 | 1.66 |

| Brisas de Córdoba | 1.51 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 21.32 | 1.25 | 1.87 |

| Chukwin Chukwa | 2.33 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 11.86 | 2.13 | 2.52 |

| El Amparo | 1.86 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 28.66 | 0.85 | 3.75 |

| El Congo | 1.55 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 15.76 | 1.38 | 1.83 |

| El Descanso | 1.67 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 14.12 | 1.41 | 1.87 |

| El Diamante | 2.07 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 14.99 | 1.86 | 2.43 |

| El Edén | 1.34 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 18.16 | 1.06 | 1.50 |

| El Esfuerzo | 1.22 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 20.91 | 0.97 | 1.48 |

| El fraile | 1.32 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 13.94 | 1.12 | 1.48 |

| El Jardín | 1.61 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 12.89 | 1.46 | 1.85 |

| El Limón | 1.69 | 0.33 | 0.58 | 34.07 | 1.03 | 2.09 |

| El Manantial | 3.09 | 0.31 | 1.21 | 39.33 | 0.39 | 4.64 |

| El Paraíso | 2.44 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 39.15 | 1.03 | 5.28 |

| El Progreso | 1.62 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 13.13 | 1.47 | 1.86 |

| El Recuerdo | 2.65 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 20.87 | 1.76 | 3.67 |

| El Triunfo | 1.66 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 11.03 | 1.52 | 1.87 |

| Emanuel | 1.24 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 10.18 | 1.10 | 1.34 |

| La Arcadia | 2.25 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 14.15 | 1.73 | 2.66 |

| La Aurora | 1.64 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 21.10 | 1.31 | 2.00 |

| La Cabaña | 1.90 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 31.50 | 0.96 | 3.24 |

| La Carmelita | 1.68 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 21.15 | 1.27 | 1.90 |

| La Cascada | 1.53 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 6.44 | 1.45 | 1.64 |

| La Chavela | 1.84 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 33.00 | 0.69 | 2.97 |

| La Conquista | 1.36 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 36.52 | 0.78 | 2.26 |

| La Esperancita | 3.67 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 20.57 | 2.87 | 4.37 |

| La Esperanza | 2.78 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 23.54 | 1.95 | 4.61 |

| La Fortuna | 1.22 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 20.92 | 0.86 | 1.52 |

| La Granja | 1.50 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 11.37 | 1.33 | 1.67 |

| La Perla | 1.40 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 14.49 | 1.27 | 1.63 |

| La Vega | 0.89 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 25.00 | 1.08 | 1.76 |

| La Victoria | 2.23 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 8.66 | 2.06 | 2.44 |

| Las Tres Palmas | 1.06 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 21.45 | 0.86 | 1.31 |

| La Esperanza | 1.39 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 26.33 | 1.05 | 1.78 |

| Las Gaviotas | 1.36 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 14.03 | 1.16 | 1.54 |

| Las Murallas | 1.89 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 29.14 | 0.84 | 2.92 |

| Las Palmas 3 | 1.76 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 23.88 | 0.74 | 2.80 |

| Las Piedritas | 1.71 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 28.44 | 0.83 | 3.04 |

| Los Acacios | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 46.43 | 0.11 | 1.77 |

| Los Angeles | 1.96 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 11.55 | 1.57 | 2.21 |

| Los Cacaos | 2.03 | 0.11 | 0.70 | 34.31 | 0.29 | 3.70 |

| Los Jazmines | 1.93 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 21.48 | 1.15 | 2.65 |

| Los Mandarinos | 2.24 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 26.93 | 0.95 | 3.53 |

| Los Mangos | 2.36 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 29.84 | 1.24 | 3.37 |

| Los Naranjos | 1.74 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 5.35 | 1.63 | 1.80 |

| Los Potreritos | 2.11 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 23.17 | 1.02 | 3.13 |

| Los Recuerdos | 1.71 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 16.83 | 0.69 | 0.97 |

| María Bonita | 1.48 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 14.78 | 1.24 | 1.67 |

| Monte Carmelo | 1.53 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 20.60 | 1.22 | 1.85 |

| Niguakoa | 2.46 | 0.17 | 0.72 | 29.17 | 1.66 | 4.40 |

| No hay como tu | 1.23 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 47.23 | 0.57 | 3.13 |

| Nuevo Oriente | 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.37 | 42.75 | 0.37 | 1.71 |

| Santa Bárbara | 1.86 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 46.23 | 0.90 | 4.50 |

| Sinaí | 2.70 | 0.15 | 0.95 | 35.06 | 0.86 | 5.35 |

| Tagbi | 1.24 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 19.33 | 1.01 | 1.49 |

| Villa Brisa | 1.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 3.62 | 1.02 | 1.09 |

| Villa Sofia | 2.05 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 19.66 | 1.29 | 2.70 |

| Villa Vista | 1.78 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 15.11 | 1.61 | 2.09 |

| Total | 1.90 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 41.61 | 0.11 | 5.35 |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | RDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.692 | 0.441 | 1.8 |

| SVR | 0.663 | 0.461 | 1.56 |

| RF–SVR | 0.853 | 0.380 | 2.6 |

| RF-Optimized XGBoost | 0.866 | 0.090 | 1.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yacomelo Hernández, M.J.; Alama, W.I.; Montenegro, A.C.; Córdoba, O.d.J.; Castañeda Sanchez, D.; Vargas García, C.; Flórez Cordero, E.; Castillo Quezada, J.; Pacherres Herrera, C.; Prado-Castillo, L.F.; et al. Application of Vis–NIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning for Assessing Soil Organic Carbon in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability 2026, 18, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010513

Yacomelo Hernández MJ, Alama WI, Montenegro AC, Córdoba OdJ, Castañeda Sanchez D, Vargas García C, Flórez Cordero E, Castillo Quezada J, Pacherres Herrera C, Prado-Castillo LF, et al. Application of Vis–NIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning for Assessing Soil Organic Carbon in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010513

Chicago/Turabian StyleYacomelo Hernández, Marlon Jose, William Ipanaqué Alama, Andrea C. Montenegro, Oscar de Jesús Córdoba, Darío Castañeda Sanchez, Cesar Vargas García, Elias Flórez Cordero, Jim Castillo Quezada, Carlos Pacherres Herrera, Luis Fernando Prado-Castillo, and et al. 2026. "Application of Vis–NIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning for Assessing Soil Organic Carbon in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010513

APA StyleYacomelo Hernández, M. J., Alama, W. I., Montenegro, A. C., Córdoba, O. d. J., Castañeda Sanchez, D., Vargas García, C., Flórez Cordero, E., Castillo Quezada, J., Pacherres Herrera, C., Prado-Castillo, L. F., & Casas Leuro, O. (2026). Application of Vis–NIR Spectroscopy and Machine Learning for Assessing Soil Organic Carbon in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability, 18(1), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010513