Service Marketing Mix and MOOC Enrollment in Thailand: Exploring Brand Image as a Mediator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Consumer Decision-Making

2.2. Service Marketing Mix Framework

2.3. Brand Image

2.4. Research Gaps

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Measurement of Constructs

3.4. Estimation Method

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the Respondents

4.2. Measurement Model

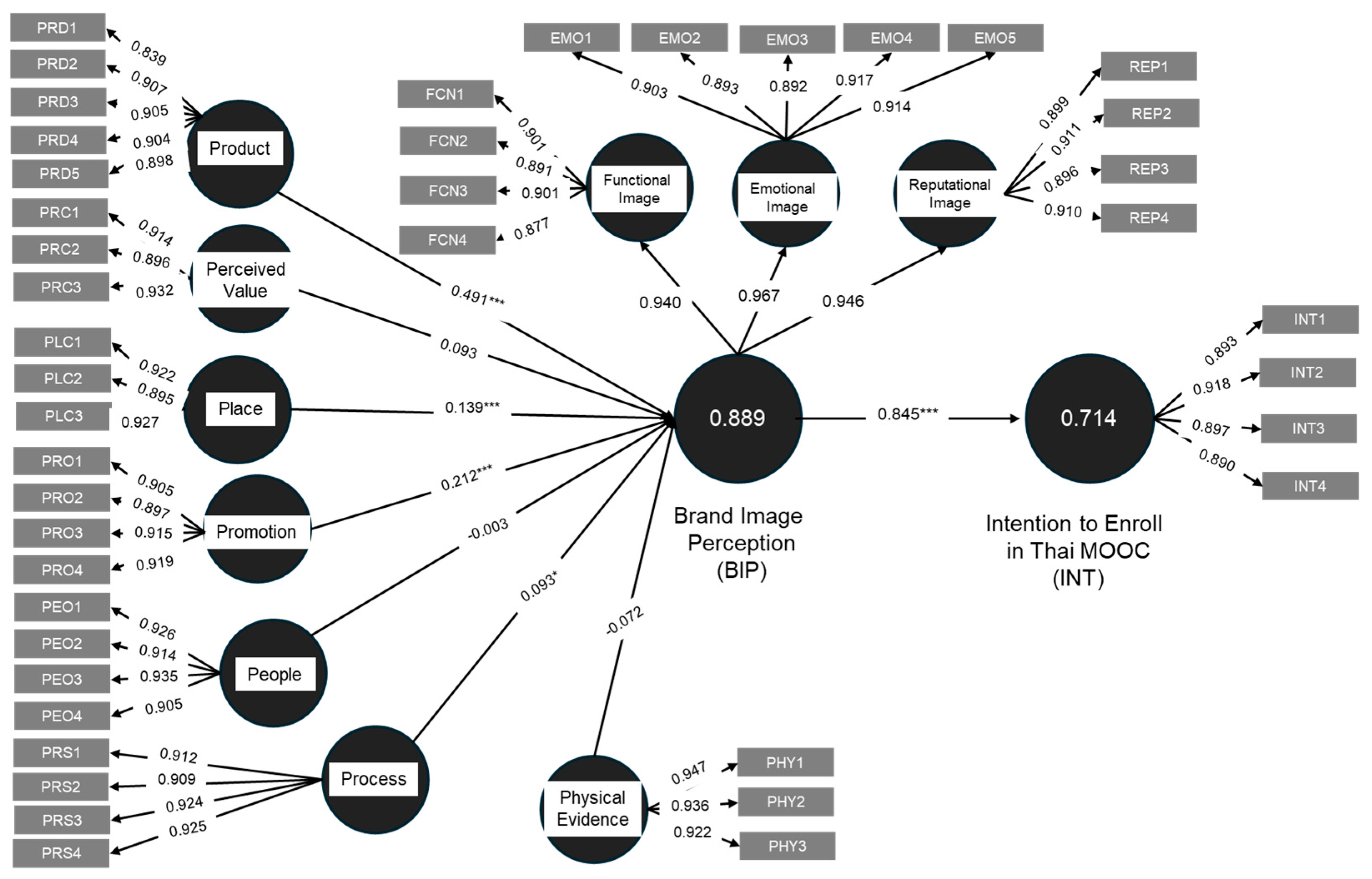

4.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Direct Effects: Marketing Mix→Brand Image Perception

5.2. Non-Significant Results: Theoretical Implications

5.3. Mediation Effects: Brand Image as Strategic Mechanism

5.4. Paradigm Shift: Digital-Native Educational Marketing

6. Research Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

7.1. Limitations of the Study

7.2. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- NSTDA. MOOCs: Educational Innovation/Technological Communication for Leapfrogging in Education. Available online: https://www.nstda.or.th/home/knowledge_post/moocs-bibliometric/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Jiang, L.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, P.; Fu, Y.; Yin, M. Reinforced explainable knowledge concept recommendation in MOOCs. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2023, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, M.; Liu, J. Analysis of factors including MOOC quality based on I-DEMATEL-ISM method. Syst. Soft Comput. 2025, 7, 200220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese-Posselt, M.; Saydan, S.; Lâm, T.; Rorig, A.; Bergmann, C.; Becker, F.; Kurzai, O.; Feufel, M.; Gastmeier, P.; Schneider, S. Development and evaluation of a MOOC to teach medical students the prudent use of antibiotics. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2025, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Yang, T.; Niu, Z.; Kim, J.K. Investigating what learners value in marketing MOOCs: A content analysis. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2024, 36, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, A.; Cartney, P.; Christie, J.; Smyth, R.; Cooke, A.; Jones, T.; Kingm, E.; White, H.; Kennedy, J. Do MOOCs encourage corporate social responsibility or are they simply a marketing opportunity? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 33, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiling, J.; Hollebrands, K. Examining the effect of active participation on the TPACK knowledge of mathematics educators in a MOOC. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2025, 9, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, J.M.; Bastos, C.; Vieira, F.; Machado, P.; Ribeiro, A.; Cabral, P.; Abreu, M. Perceived usefulness of a MOOC on healthcare during the pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, R.H.; Ezeh, O.V.; Teck, T.S.; Sorooshian, S. The disruptive power of MOOCs. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2020, 10, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Arteaga, J.; Leton, E.; Perez-Martin, J.; Molanes-Lopez, A.; Rodriguez-Ascaso, A. Assessment of captions’ quality by students of a MOOC. Comput. Educ. Open 2025, 9, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica, A.; Villanueva, E.; Lodeiros-Zubiria, M.L. Micro-learning platforms brand awareness using social-media marketing and customer brand engagement. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Fu, S.; Xu, J.; Edusei-Mensah, W.; Li, Y. Pathway from learning engagement to innovative entrepreneurial intentions in MOOCs. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e70338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai MOOC. Thai MOOC Academy. Available online: https://thaimooc.ac.th (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Sirisuthikul, V. Building a R.I.C.H. brand in 10 hours: Teaching sustainability concepts through Thai MOOC. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2023, 13, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Standard. Knowing Thai MOOC: A National Online Platform for Lifelong Learning. Available online: https://thestandard.co/thai-mooc/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- TKPark. Thai MOOC: Important Step of Education for All. Available online: https://www.tkpark.or.th (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ponnen, P.; Riyanti, R.D. A decade of MOOC in Asian higher education. Asian J. Educ. 2025, 21, 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Scalamonti, F. The Sustainable Development Index: An ecological-governance perspective. Highl. Sustain. 2024, 3, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- But, T.; Pulina, T.; Bielan, O.; Zidova, V. Assessment of the development potential of the tourism industry in Czechia. Econ. Manag. 2025, 28, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tongpaeng, Y.; Sureephong, P.; Chernbumroong, S.; Kamon, M.; Tabai, K. Vocational knowledge improvement for post-modern workers. ECTI-CIT Trans. 2019, 13, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasritha, K.; Angskun, J.; Angskun, T. Factors analysis of affective assessment in electronic education. Suranaree J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 14, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Wisenblit, J. Consumer Behavior, 12th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ivy, J. A new higher education marketing mix: 7Ps for MBA marketing. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2008, 22, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M. Marketing education: Service quality perceptions among international students. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, D.; Sinaga, O.; Saudi, M.H.B.M. The impact of 7Ps of marketing on the performance of higher education institutions. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. 2021, 11, 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Pardiyono, R.; Suteja, J.; Puspita, H.D.; Undang, J. Dominant factors for the marketing of private higher education. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, R.; Lettice, F.; Nadeau, J. Anthropomorphized university marketing. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2016, 27, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhana, P.; Noermijati, N.; Hussein, A.S.; Indrawati, N.K. Moderated mediation of low enrollment intention. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2023, 36, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.; Ennew, C.; Kortam, W. Brand equity in higher education. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanoves-Boix, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Lorente-Ayala, J.M. Brand equity in higher education: Strategies for Spanish public universities. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2025, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, J.; D’Alessandro, S.; Johnson, L.; White, L. MOOCs and consumer goals. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 46, 994–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.H.; Nayak, R.; Van Nguyen, L.T. Social brand engagement in higher education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, P.; Golahit, S. Service marketing mix in higher education. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 12, 151–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharov, S.; Biliatska, V.; Kolmakova, V.; Chernova, G.; Miroshnichenko, M. Use of MOOCs by university teachers. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2025, 15, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verykios, V.S.; Alachiotis, N.S.; Paxinou, E.; Feretzakis, G. Behavioral patterns in MOOCs using hidden Markov models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide-Pulido, P.; Gutiérrez-Villar, B.; Carbonero-Ruz, M.; Alves, H. Determinants of university brand image. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2022, 34, 692–710. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F. SmartPLS 4: Next-Generation Path Modeling Software; SmartPLS GmbH: Oststeinbek, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Taecharungroj, V. Improving learning experience in MOOCs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Pahlevan Sharif, S.; Ray, A.; Khong, K.W. MOOC perceived quality and emotional experience. Online Inf. Rev. 2023, 47, 582–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snadrou, D.; Haoucha, M. The role of brand image in higher education choice. J. Mark. Res. Case Stud. 2024, 224523. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent Profile | Frequency (%) | Respondent Profile | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 210 (44.2) | Occupation | |

| Female | 265 (55.8) | Government officers | 229 (48.2) | |

| Age | 19–24 | 96 (20.2) | Employees | 88 (18.5) |

| 25–30 | 68 (14.3) | Business owners | 66 (13.9) | |

| 31–36 | 105 (22.1) | Students | 66 (13.9) | |

| 37–42 | 76 (16.0) | Not mentioned | 26 (5.5) | |

| 43–48 | 64 (13.5) | Education Level | ||

| 49–54 | 38 (8.0) | Below bachelor’s degree | 78 (16.4) | |

| 55–60 | 17 (3.6) | Bachelor’s degree | 240 (50.5) | |

| Above 60 | 11 (2.3) | Above bachelor’s degree | 157 (33.1) | |

| Construct | Indicators | Mean | S.D. | Loading | Alpha | ρA | ρC | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Marketing Mix (7Ps) | ||||||||

| Product (PRD) | PRD1–PRD5 | 4.375–4.482 | 0.581–0.614 | 0.893–0.907 | 0.935 | 0.936 | 0.951 | 0.794 |

| Perceived Value (PRC) | PRC1–PRC3 | 4.48–4.516 | 0.567–0.596 | 0.896–0.932 | 0.901 | 0.903 | 0.938 | 0.835 |

| Place (PLC) | PLC1–PLC3 | 4.484–4.507 | 0.571–0.606 | 0.895–0.927 | 0.902 | 0.902 | 0.939 | 0.836 |

| Promotion (PRO) | PRO1–PRO4 | 4.396–4.463 | 0.602–0.626 | 0.897–0.919 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.950 | 0.826 |

| People (PEO) | PEO1–PEO4 | 4.478–4.507 | 0.567–0.599 | 0.905–0.935 | 0.939 | 0.940 | 0.957 | 0.846 |

| Process (PRS) | PRS1–PRS4 | 4.408–4.444 | 0.604–0.637 | 0.909–0.925 | 0.938 | 0.939 | 0.955 | 0.842 |

| Physical Evidence (PHY) | PHY1–PHY3 | 4.421–4.463 | 0.601–0.623 | 0.922–0.947 | 0.928 | 0.928 | 0.954 | 0.874 |

| Brand Image Perception | ||||||||

| Functional (FCN) | FCN1–FCN4 | 4.440–4.500 | 0.553–0.597 | 0.877–0.901 | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.940 | 0.797 |

| Emotional (EMO) | EMO1–EMO5 | 4.410–4.450 | 0.598–0.628 | 0.892–0.917 | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.957 | 0.816 |

| Reputational (REP) | REP1–REP4 | 4.430–4.490 | 0.584–0.603 | 0.896–0.911 | 0.925 | 0.925 | 0.947 | 0.817 |

| Intention to Enroll | ||||||||

| Intention to Enroll (INT) | INT1–INT4 | 4.440–4.480 | 0.585–0.624 | 0.890–0.918 | 0.921 | 0.922 | 0.944 | 0.809 |

| PRD | PRC | PLC | PRO | PEO | PRS | PHY | BIP | INT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product (PRD) | - | ||||||||

| Perceived Value (PRC) | 0.640 | - | |||||||

| Place (PLC) | 0.657 | 0.716 | - | ||||||

| Promotion (PRO) | 0.650 | 0.641 | 0.663 | - | |||||

| People (PEO) | 0.666 | 0.727 | 0.728 | 0.704 | - | ||||

| Process (PRS) | 0.683 | 0.661 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.716 | - | |||

| Physical evidence (PHY) | 0.673 | 0.703 | 0.698 | 0.697 | 0.740 | 0.765 | - | ||

| Brand image perception (BIP) | 0.671 | 0.695 | 0.705 | 0.661 | 0.705 | 0.669 | 0.678 | - | |

| Intention to enroll in Thai MOOC (INT) | 0.615 | 0.692 | 0.694 | 0.614 | 0.692 | 0.641 | 0.655 | 0.678 | - |

| Construct | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Brand image perception (BIP) | 0.889 | 0.888 |

| Intention to enroll in Thai MOOC (INT) | 0.714 | 0.714 |

| Construct | Brand Image Perception (BIP) |

|---|---|

| Product (PRD) | 0.310 |

| Perceived Value (PCS) | 0.014 |

| Place (PLC) | 0.030 |

| Promotion (PRO) | 0.092 |

| People (PEO) | 0.000 |

| Process (PRS) | 0.028 |

| Physical evidence (PHY) | 0.007 |

| Cross-Validated Redundancy | Cross-Validated Communality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 | Prediction Capability | Q2 | Prediction Capability | |

| Brand image perception (BIP) | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.886 | 0.886 |

| Intention to enroll in Thai MOOC (INT) | 0.737 | 0.737 | 0.777 | 0.777 |

| Direct Effect Testing | β | t-test | p Values | f-sq | Results |

| PRD → BIP (H1a) | 0.491 *** | 8.184 | 0.000 | 0.310 | Supported |

| PRC → BIP (H1b) | 0.093 | 1.910 | 0.056 | 0.014 | Not Supported |

| PLC → BIP (H1c) | 0.139 ** | 2.768 | 0.006 | 0.030 | Supported |

| PRO → BIP (H1d) | 0.212 *** | 4.194 | 0.000 | 0.092 | Supported |

| PEO → BIP (H1e) | −0.003 | 0.053 | 0.958 | 0.000 | Not Supported |

| PRS → BIP (H1f) | 0.141 * | 2.369 | 0.018 | 0.028 | Supported |

| PHY → BIP (H1g) | −0.072 | 1.277 | 0.202 | 0.007 | Not Supported |

| BIP → INT (H2) | 0.845 *** | 44.519 | 0.000 | 2.499 | Supported |

| Indirect Effect Testing | β | t-test | pValues | f-sq | Results |

| PRD → BIP → INT (H3a) | 0.179 *** | 4.231 | 0.000 | - | Supported |

| PRC → BIP → INT (H3b) | 0.079 | 1.901 | 0.057 | - | Not Supported |

| PLC → BIP → INT (H3c) | 0.118 ** | 2.752 | 0.006 | - | Supported |

| PRO → BIP → INT (H3d) | 0.179 *** | 4.231 | 0.000 | - | Supported |

| PEO → BIP → INT (H3e) | −0.003 | 0.053 | 0.958 | - | Not Supported |

| PRS → BIP → INT (H3f) | 0.119 * | 2.360 | 0.018 | - | Supported |

| PHY → BIP → INT (H3g) | −0.061 | 1.276 | 0.202 | - | Not Supported |

| Brand Image Perception (BIP) R2 = 0.889 | Intention to Enroll in Thai MOOC (INT) R2 = 0.714 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | t-Test | IE | TE | DE | t-Test | IE | t-Test | TE | |

| Product (PRD) | 0.491 *** | 8.184 | - | 0.491 *** | - | - | 0.179 *** | 4.231 | 0.415 *** |

| Perceived Value (PRC) | 0.093 | 1.910 | - | 0.093 | - | - | 0.079 | 1.901 | 0.079 |

| Place (PLC) | 0.139 ** | 2.768 | - | 0.139 ** | - | - | 0.118 ** | 2.752 | 0.118 ** |

| Promotion (PRO) | 0.212 *** | 4.194 | - | 0.212 *** | - | - | 0.179 *** | 4.231 | 0.179 *** |

| People (PEO) | −0.003 | 0.053 | - | −0.003 | - | - | −0.003 | 0.053 | −0.003 |

| Process (PRS) | 0.093 * | 2.369 | - | 0.093 * | - | - | 0.119 * | 2.360 | 0.119 * |

| Physical evidence (PHY) | −0.072 | 1.277 | - | −0.072 | - | - | −0.061 | 1.276 | −0.061 |

| Brand image perception (BIP) | - | - | - | 0.845 *** | 44.519 | - | 0.845 *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wathanakom, N.; Juicharoen, N.; Saranrom, A.; Amornrit, P.; Nadprasert, P. Service Marketing Mix and MOOC Enrollment in Thailand: Exploring Brand Image as a Mediator. Sustainability 2026, 18, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010508

Wathanakom N, Juicharoen N, Saranrom A, Amornrit P, Nadprasert P. Service Marketing Mix and MOOC Enrollment in Thailand: Exploring Brand Image as a Mediator. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010508

Chicago/Turabian StyleWathanakom, Narubodee, Nhatphaphat Juicharoen, Aphiradee Saranrom, Phantipa Amornrit, and Phisit Nadprasert. 2026. "Service Marketing Mix and MOOC Enrollment in Thailand: Exploring Brand Image as a Mediator" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010508

APA StyleWathanakom, N., Juicharoen, N., Saranrom, A., Amornrit, P., & Nadprasert, P. (2026). Service Marketing Mix and MOOC Enrollment in Thailand: Exploring Brand Image as a Mediator. Sustainability, 18(1), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010508