1. Introduction

Climate change has evolved into one of the most acute global challenges, predominantly fueled by the relentless rise in greenhouse gas emissions [

1,

2,

3]. As one of the world’s top fossil fuel consumers, China confronts substantial hurdles in mitigating climate change in the years ahead [

4,

5]. The imperative to curb carbon emissions and transition toward sustainable practices has spurred the adoption of diverse carbon pricing mechanisms, such as emissions trading systems [

6,

7]. While extensive research has been conducted on carbon emission rights allocation at China’s provincial level, notable gaps persist owing to regional disparities—with the lack of granularity impeding timely responses to local emission dynamics. Analyzing cities with greater homogeneity can refine management, monitoring, and emission reduction strategies by addressing variations in input-output indicators [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Since 2018, China has vigorously advanced the development of urban agglomerations to facilitate regional industrial integration and boost interactive growth [

14,

15,

16,

17]. These agglomerations have emerged as a cornerstone of national development strategies, propelling economic growth, enhancing regional coordination, and elevating international competitiveness [

18]. Yet, while fueling economic vitality, urban agglomerations—particularly high-density ones—are associated with surging energy consumption and pollutant emissions [

19]. This dual challenge underscores the urgent need for targeted research on carbon emission rights allocation, especially in critical regions like the Yangtze River Delta (YRD). Despite its prominent economic status, the YRD has witnessed a steady uptick in carbon emissions, reflecting a misalignment between economic expansion and environmental sustainability. Addressing carbon emissions in this urban cluster is therefore pivotal to advancing China’s dual environmental and economic goals.

Prior research on carbon emission allocation has predominantly centered on efficiency and equity as the core principles guiding allocation scheme design [

20,

21]. Efficiency is typically evaluated via methodologies such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), whereas equity seeks to balance the interests of diverse social groups, regions, and generations. Yet, reconciling these dual objectives remains a formidable challenge in practice. Most existing models adopt single-stage allocation approaches that neglect the dynamic interactions and spatial heterogeneity of carbon emissions across regions and cities [

22,

23,

24]. For example, cities situated along major wind corridors may be disproportionately impacted by emissions originating from adjacent urban centers. Neglecting such interconnections may lead to inequitable carbon quota allocations and suboptimal results. Since CO

2 emissions are shaped by meteorological factors (e.g., wind direction and speed) and transcend administrative boundaries, grasping the spatial dynamics of emission transmission is imperative. As urban agglomerations such as the YRD expand, their interconnectedness necessitates a reassessment of carbon credit allocation frameworks to more effectively address the inherent spatial spillover effects of these systems.

This research aims to address these challenges by employing a two-stage network DEA model that accounts for reciprocal CO2 transport to allocate carbon emission rights across the Yangtze River Delta city cluster. A backward trajectory model is utilized to analyze transmission rates among the three provinces and one municipality within the region based on wind patterns and CO2 concentrations. Following this, a robust two-stage network DEA model is developed, assigning total carbon emission allowances to each city with weights based on allowances obtained in each of the two stages. Additionally, to mitigate economic impacts stemming from emission reductions and enhance efficiency, the allocation model incorporates constraint coefficients based on each city’s GDP protection and energy consumption.

To guide the research implementation and address the identified gaps, the following specific research questions (RQs) are proposed:

RQ1: How to quantitatively characterize the inter-city CO2 spillover effects in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, and what roles do meteorological factors play in shaping these transmission dynamics?

RQ2: Can a two-stage network DEA model integrating emission generation and governance capacities optimize the fairness and efficiency of carbon emission rights allocation, compared with traditional single-stage or emission-centric models?

RQ3: How does the proposed allocation framework balance economic development and environmental governance to provide actionable policy implications for urban agglomerations?

This study makes significant contributions to the field of carbon emission rights allocation, with four key innovations: first, unlike traditional models that allocate carbon emission rights solely within individual cities, this research incorporates CO2 transmission between cities, considering regional spillover effects. By accounting for the movement of CO2 influenced by meteorological factors such as wind patterns, this model offers a more nuanced and realistic approach to emission distribution across interconnected urban areas.

Second, the study employs the MEIC inventory data within the WRF (Weather Research and Forecasting) environment, departing from the conventional emission factor method. This integration enhances the accuracy and granularity of carbon emission quantification by utilizing high-resolution meteorological and pollutant data, which more precisely reflects the actual emission scenarios in the Yangtze River Delta.

Third, the introduction of a two-stage network Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model represents a methodological advancement. This model not only optimizes carbon emission rights allocation but also accounts for both CO2 generation and management efficiencies across multiple stages, contrasting with previous single-stage approaches that may overlook dynamic interactions and regional heterogeneity in emission reductions.

Finally, this study provides a comprehensive framework for balancing economic growth and carbon emission control in the Yangtze River Delta. By incorporating GDP protection and energy consumption constraints, the model minimizes the economic impact on cities during emission reduction efforts while ensuring sustainable urban development. Additionally, it proposes strategies for achieving carbon peaking and gradual reduction, promoting a holistic approach to environmental sustainability.

The remaining sections of the paper are structured in the following manner:

Section 2 presents the related works.

Section 3 focuses on the development and analysis of the proposed model.

Section 4 covers the allocation results and discussions.

Section 5 provides conclusions and policy suggestions.

2. Related Works

The allocation of carbon emission rights is critical for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, with extensive related research focusing on key principles, methodologies, and spatial scales. Existing studies in this field primarily center on two core principles: fairness and efficiency. Fairness in allocation typically advocates for equal distribution of emission allowances, aiming to protect the developmental rights of different regions and populations [

11,

25]. However, while this approach addresses social equity, it often compromises overall efficiency, as an equal distribution might not optimize resource usage across diverse regions and sectors [

26]. On the other hand, efficiency seeks to maximize societal benefits from emission reductions by focusing on the optimal use of resources [

23,

27,

28]. Efficiency can be evaluated through two main perspectives: input-output efficiency, which measures emissions relative to inputs, and marginal abatement cost efficiency, which considers the cost-effectiveness of emission reductions [

29,

30].

In terms of research methodologies, carbon emission rights allocation has been approached through a variety of strategies, including optimization, game theory, indicator synthesis, and hybrid models [

31,

32,

33]. Optimization methods, particularly Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), are frequently used to solve linear and nonlinear programming challenges in allocation models [

34,

35]. While DEA-based models such as BCC-DEA, SBM-DEA, two-stage network DEA, and DDF/NDD have become widely adopted, they focus on optimizing carbon resource allocation based on efficiency, often leaving fairness concerns underexplored [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Game-theoretic models, often employed in studies involving multiple stakeholders such as governments, enterprises, and societies, offer insights into how these parties can negotiate and collaborate to achieve efficient allocation. However, these models may sometimes lead to inefficiencies due to individual actors prioritizing self-interest [

51]. Indicator synthesis models, which integrate multiple criteria such as equity and efficiency, seek to improve the acceptability and applicability of carbon allocation strategies. Despite their ability to balance multiple objectives, the main challenge lies in the disparity of assessment standards and weighting factors, which can result in significant variations in allocation outcomes [

52]. Hybrid models, combining different methodologies, are also used to address the complexity of the allocation problem and enhance the robustness of the solutions.

Research on carbon emission rights allocation in China has primarily focused on three levels: national, provincial, and urban. At the national level, early studies emphasized the importance of fairly distributing emission reduction responsibilities across provinces to ensure national economic stability while achieving emission reduction targets. These studies explored resource distribution strategies that balanced efficiency and equity. They identified regional disparities in carbon utilization, with eastern China showing the lowest carbon efficiency, followed by the central and western regions, which demonstrated relatively better carbon utilization rates [

53,

54]. At the provincial level, studies have often employed compensatory mechanisms to optimize provincial benefits, ensuring smooth execution of allocation programs and addressing efficiency concerns. At the urban level, city-specific research has focused on ensuring that each city’s carbon emission rights align with national and regional goals. The study of urban clusters, such as those in the Pearl River Delta, highlights the importance of strategic allocation in reducing urban disparities and fostering sustainable development [

55].

The literature on transboundary CO

2 transport and atmospheric modeling has also gained prominence in recent years. Researchers have utilized regional air quality models, such as WRF-CMAQ and WRF-Chem, to study the dynamics of CO

2 emissions across different regions [

56]. These models help to understand how emissions from one city or province can impact neighboring regions, providing insights into the inter-regional spillover effects that should be considered in carbon emission rights allocation [

57]. These modeling approaches have significantly advanced the understanding of atmospheric pollutants, including CO

2, and have been critical in designing allocation frameworks that consider transboundary emission flows [

58]. Additionally, other methodologies such as the Gaussian Plume Model and spatial correlation analysis using GIS have been employed to quantify emissions and their transboundary effects [

59]. However, these methods often face limitations, such as high computational costs or reliance on simplifying assumptions that can introduce uncertainty in the results [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

Despite the progress in these areas, gaps remain in the literature, particularly in integrating spatial spillover effects and dynamic regional interactions into carbon emission rights allocation models. While many studies focus on carbon emission efficiency and fairness at a single level (e.g., provincial or national), there is less focus on the interconnectedness of urban agglomerations and their impact on emission dynamics. Furthermore, although various models have been developed to optimize allocation, incorporating meteorological influences and transboundary CO

2 transport into these models remains underexplored. There is also increasing interest in the application of artificial intelligence models and statistical techniques for forecasting carbon emissions and improving allocation processes, though this area still lacks comprehensive exploration [

51,

52].

This study aims to fill these gaps by integrating the dynamics of CO2 transmission across regions, employing innovative modeling techniques, and proposing strategies for sustainable urban development within the Yangtze River Delta, a key urban agglomeration in China. By addressing the interconnectedness of cities and accounting for transboundary emissions, this research contributes to a more comprehensive and effective framework for carbon emission rights allocation that aligns economic, environmental, and social objectives.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Indicator Selection

3.1.1. Research Objective

The Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region has demonstrated remarkable economic growth, outpacing the national average. By the end of 2024, its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is projected to exceed 32 trillion yuan, contributing approximately 25.2% of China’s total economic output. Given its substantial economic activity and high population density, the YRD presents a critical area for research on the equitable distribution of carbon emission rights at a national level. The cities within the YRD urban agglomeration are primarily located on the relatively low-lying YRD plains, which exhibit significant uniformity [

66]. This homogeneity across the region makes the allocation of emission rights at the urban agglomeration level more accurate and fairer compared to provincial-level allocations, which may overlook regional disparities. For this reason, this study focuses on the 27 cities within the Yangtze River Delta region, aiming to refine emission rights allocation through a more localized and representative approach (see

Figure 1).

3.1.2. Configuration of a Model to Simulate the Trajectory in Reverse

Urban agglomerations play a pivotal role in reducing carbon emissions, as they represent highly interconnected spatial units [

67]. However, not all urban areas in China exhibit a polycentric spatial structure, and this structure does not necessarily lead to reduced emissions. In fact, polycentric regions may inadvertently promote carbon emissions due to the complex dynamics of inter-city interactions. Research indicates that the YRD urban agglomeration adopts a polycentric model, which can influence carbon emissions both positively and negatively [

68]. To better understand these dynamics, previous studies have focused on representative cities such as Nanjing, Shanghai, and Ningbo, exploring seasonal variations in pollutants like PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and nitro-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (NPAHs), as well as the correlation between O

3 and the stratosphere, considering the effects of tropical storms [

25,

69]. Notably, Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Hefei have been identified as key centers within the YRD urban agglomeration. This study evaluates these central cities and the surrounding areas in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces for their influence on carbon emissions across the region.

To simulate the dispersion of CO

2 across the YRD, this study utilizes the MeteoInfo 4.1.4 to generate backward trajectory models [

70]. These models account for atmospheric transport and CO

2 dispersion, recognizing that CO

2, unlike other pollutants such as SO

2 and O

3, does not undergo significant chemical transformations in the atmosphere. This method provides a more precise model of CO

2 distribution, considering the region’s meteorological conditions and their impact on emissions.

3.1.3. Optimal Configurations for Two-Stage Network DEA Variables

This study synthesizes a range of input and output indicators for CO

2 emissions, as identified by previous scholars.

Table 1 summarizes these indicators, revealing a consistent emphasis on GDP as the primary output in emission rights allocation, with CO

2 emissions being treated as the undesirable output. Commonly, three key input dimensions are prioritized in existing literature: human capital, financial resources, and material factors. In this study, the specific inputs used are energy consumption, fixed asset investment, and labor force size, all of which are critical factors in understanding the sources of carbon emissions. The desired output is GDP, while CO

2 emissions, as derived from emission inventories in the WRF model, represent the unwanted byproduct of the region’s economic activities.

To simulate CO

2 concentrations in the YRD region, this study uses WRFv4.0 (Weather Research and Forecasting model), which integrates the 2020 MEIC emission inventory from Tsinghua University. This inventory provides accurate data on anthropogenic emissions, which is crucial for the simulation [

71]. The model simulates carbon emissions from 1 January to 31 December 2020, with a focus on the 27 cities within the YRD urban agglomeration. By using these advanced models and data sources, the study aims to provide a more granular and accurate picture of carbon emissions within the YRD, ensuring that the carbon emission rights allocation system is both efficient and equitable.

The selection of 2020 as the simulation period is primarily based on two considerations: first, the MEIC emission inventory for 2020 provides high-resolution anthropogenic emission data covering the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, which is compatible with the WRF model’s spatial-temporal resolution requirements for simulating inter-city CO

2 transmission. Second, while 2020 was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Yangtze River Delta region resumed industrial and transportation activities relatively early, with near-normal economic operations from late March onward. Besides, the core drivers of the carbon emission rights allocation framework proposed in this study—atmospheric transport dynamics and urban governance capacity—are structural and long-term factors that are not significantly distorted by short-term pandemic shocks. Specifically, the wind direction, wind speed, and other meteorological conditions that dominate inter-city CO

2 spillover effects are consistent with long-term climatic averages in the YRD [

72], and there is no evidence of abnormal meteorological events in 2020 that would alter the spatial transmission patterns of CO

2. Meanwhile, urban governance capacity indicators (e.g., environmental protection investment, number of green patents, green space area) reflect long-term policy commitments and technological accumulation, which are not affected by short-term economic fluctuations caused by lockdowns or reduced transportation. Detailed indicators are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of selected indicators from relevant literature.

Table 1.

Summary of selected indicators from relevant literature.

| Author | Input Variables | Expected Outputs | Unexpected Results |

|---|

| Guo, Zhao [73] | Labor force | GDP | PM2.5 emission |

| Coal |

| Capital |

| Gas |

| Miao, Geng [74] | Capital stock | GDP | CO2 emission |

| Population |

| Energy consumption |

| Zhao, Wu [75,76] | Labor input | GDP | Pollutant production |

| Energy consumption |

| Fixed asset input |

| Cai and Ye [8] | CO2 emissions allowances | GDP | |

| Population |

The second tier of carbon emission rights allocation is strongly influenced by municipal governance processes. Cities that demonstrate effective governance are rewarded with increased emission allowances, while cities with less effective governance will need to purchase carbon permits from municipalities with stronger governance systems. This system places significant emphasis on CO2 governance, wherein cities excelling in governance practices are incentivized with financial support for initiatives such as industrial upgrading and environmental protection. These investments are intended to foster long-term, sustainable development within the urban agglomeration.

Environmental governance effectiveness has been extensively studied and is closely tied to government actions, particularly investments in environmental protection funds. Such investments are essential in enhancing a city’s capacity for self-purification, which is not only reflected in environmental indicators like green space coverage and forest preservation rates but also in the broader success of carbon reduction efforts [

77]. Research has shown that municipalities that prioritize governance systems aligned with environmental sustainability tend to see better overall management of CO

2 emissions and related environmental impacts [

78,

79].

Furthermore, excessive CO

2 emissions contribute to rising global temperatures and intensify extreme weather events. The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2035, issued by 17 Chinese departments in 2022, acknowledges the growing risks posed by global climate instability [

80]. This strategy underscores the importance of addressing climate change and extreme weather as major medium- to long-term challenges that impact ecosystems, economies, and social structures worldwide. In line with this, the study uses the frequency of severe weather events as an adverse outcome indicator for evaluating CO

2 management efforts. Additionally, Air Quality Index (AQI) values that meet or exceed the second threshold are employed as a desired outcome, helping to gauge the effectiveness of CO

2 reduction strategies. The study draws on data from the 2020 Statistical Yearbook, with extreme weather data provided by the National Meteorological Centre for comprehensive statistical analysis. These sources provide critical insight into the relationship between governance, environmental protection efforts, and CO

2 emission management within the urban agglomeration. The variables used in this study are shown in

Table 2.

3.2. The Two-Stage Network DEA Framework

In carbon credit allocation, much of the current literature primarily focuses on the formation of carbon dioxide emissions [

22]. For example, studies often highlight the consumption of fossil energy, economic indicators such as GDP, and labor availability [

81,

82]. However, relatively few researchers have addressed the post-production treatment of CO

2, which plays a crucial role in mitigating climate change and ensuring societal well-being [

83,

84]. This paper employs a two-stage network DEA (Data Envelopment Analysis) model to allocate carbon emission quotas within the Yangtze River Delta Group. The model considers 27 cities as distinct Decision-Making Units (DMUs), where each city receives carbon emission quotas from two combined stages. The goal is to create an efficient allocation model that also prioritizes sustainable development, balancing both economic and environmental objectives. A key aspect of this model is its incorporation of inter-city CO

2 transmission due to atmospheric transport, acknowledging that emissions from one city can affect neighboring areas, influencing their treatment stage. The research framework is shown in

Figure 2. The framework takes 27 cities in the Yangtze River Delta as Decision-Making Units, integrates inter-city CO

2 transmission effects caused by atmospheric transport, and divides the allocation process into two stages: CO

2 generation (Stage 1) and CO

2 governance (Stage 2). Key input-output indicators for each stage (e.g., energy consumption, GDP, green patents, AQI-compliant days) are incorporated to balance efficiency, equity, and sustainability.

The primary approaches in multi-objective models include constraint-based methods, multi-stage approaches, and other strategies [

85]. This paper introduces the concept of sustainable development through a unique approach inspired by Yu, Jian [

86]. It sets constraints on the quota and energy shares that a city (j DMU) can earn in each phase, ensuring these do not exceed a specified threshold. Additionally, each city’s GDP share in both phases is confined to a range of values between 0 and 1. Unlike previous models that assume equal importance of both stages, this study uses an additive rule, allocating a weighting factor of 0.5 to each stage, reflecting their equal significance in the distribution of carbon credits. This equal weighting is supported by academic consensus and policy orientations: recent studies on multi-stage carbon allocation emphasize that emission generation (as a reflection of regional economic development reality) and governance capacity (as a core driver of long-term emission reduction) are mutually indispensable for equitable and sustainable quota distribution [

87,

88], while China’s “Dual Carbon” policy framework explicitly advocates for synergizing economic development with environmental governance [

89], justifying the balanced prioritization of both stages.” Because CO

2 emissions from one city can impact others due to atmospheric transport, this study modifies the classical two-stage network DEA model. The new model (

Figure 3) accounts for these inter-city effects, enhancing the allocation’s fairness and efficiency.

The particular model is built in the following manner:

The final quota for CO

2 for the

city is:

In Equation (1), the variable reflects the value of overall efficiency. The variable is the weighting factor for the CO2 allowance in Phase I, and the variable is the weighting factor for the CO2 allowance in Phase II. represents the carbon dioxide (CO2) allowance for the city in phase I, whereas represents the CO2 allowance for the city in phase II. The variable denotes the weighting factor for the first output in phase I, while represents the weighting factor for the first output in phase II. represents the output of the city during the first phase, while represents the output of the city during the second phase. The variable represents the weighting factor for the input in the first stage, whereas represents the weighting factor for the input in the second stage, excluding CO2. indicates the value of the input for the city during the first phase, while shows the value of the input for the city during the second phase.

3.3. Genetic Algorithm-Based Optimization

Optimization problems are fundamental in decision-making and planning across various domains, with classical approaches such as linear programming and integer programming being well-established tools [

90,

91]. Traditional methods like the Simplex algorithm and interior point algorithms have been widely used to solve linear optimization challenges efficiently [

92,

93]. However, real-world problems frequently involve nonlinear optimization tasks, which present significant challenges to conventional linear techniques in achieving optimal solutions. In this study, the equation under investigation represents a nonlinear optimization problem, which often eludes effective resolution by traditional linear optimization methods.

As demonstrated in the work of Meng and Ge, a diagonal algorithm was employed to address nonlinear optimization models with variational inequalities [

94]. However, this study proposes the adoption of a genetic algorithm for optimizing parameter solutions [

95]. The genetic algorithm is particularly well-suited for global search tasks, significantly reducing the risk of getting trapped in local optima [

96]. Unlike traditional gradient-based methods, such as Newton’s iterative approach or interior-point methods, genetic algorithms operate independently of gradient information, making them particularly useful for non-differentiable objective functions or complex gradient computations [

97,

98,

99,

100].

One of the key strengths of genetic algorithms lies in their ability to maintain population diversity through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. This enables comprehensive exploration of the solution space, facilitating the discovery of globally optimal solutions even in high-dimensional and complex problems. Unlike heuristic algorithms, which may suffer from local search limitations, genetic algorithms offer greater robustness. They are capable of efficiently handling nonlinear optimization problems without being constrained by the dimensionality or complexity of the problem. This paper highlights the advantages of genetic algorithms, especially when dealing with high-dimensional and complex nonlinear optimization scenarios. The following section outlines the methodology for addressing the system of nonlinear equations using this powerful technique.

3.3.1. Initializing Populations

A population consisting of

individuals (solutions) is initially created. Every person is characterized by a chromosome, which is composed of parameters.

where

represents the

individual whose gene is represented as a parameter vector.

3.3.2. Adequacy Assessment

Define the fitness function

, which is a tool when assessing the worth of each individual. The fitness function typically exhibits an inverse relationship with the objective problem, meaning that a greater fitness value corresponds to a better objective value.

Let represents the objective function that we aim to minimize.

3.3.3. Choose an Operation

Selection of individuals for the following generation is determined by their level of fitness. Two often employed selection procedures are roulette selection [

85] and tournament selection [

101,

102].

where

denotes the probability that an individual

is selected.

3.3.4. Genetic Recombination

Two individuals are selected as a double generation and new individuals (offspring) are generated by crossover. Crossover can be done by single point crossover, two points crossover or uniform crossover. Let the two parents be

and

. Single-point crossover: choose a crossover point k, and generate two offspring Autumn and

as follows:

3.3.5. Mutation Operation

In order to preserve population variety and avoid premature convergence, mutational lifting introduces a random disturbance on the motifs of each new individual. Genes can be selected at random and their values can be altered to create variation.

where

symbolizes a minor, unpredictable disturbance used to change the value of gene

.

3.3.6. Alternative Procedure

By choosing from double and offspring generations according to fitness values, old individuals are removed and new ones are introduced, creating a new population. A flexible selection approach is frequently applied, meaning that members of the next generation who are more fit are chosen.

where

indicates selection lifting and

is the population of offspring produced by crossover and mutation lifting.

3.3.7. Termination Requirements

Specify termination criteria, such as the maximum number of iterations

or the adaptation

reaching a specific threshold

, to halt the process. Usually, either the population fitness change falls below a predetermined threshold or the maximum number of iterations is reached.

4. Results

4.1. WRF Simulation Results

Although the WRF simulation covered the entire period from 1 January to 31 December 2020,

Figure 4 presents the validation results for January 2020 as a representative month. January was selected because it exhibits typical winter meteorological conditions in the Yangtze River Delta (e.g., prevailing northeast winds and stable atmospheric stratification), which are crucial for testing the model’s capability to reproduce CO

2 dispersion under strong inversion and low-mixing environments. The validation confirmed the consistency between simulated and observed CO

2 concentrations for this month, and similar agreement was also found in other randomly checked months. Therefore,

Figure 4 serves as a representative example, while the allocation analysis was conducted using the full-year simulation results.

As shown in

Figure 4, the simulated urban CO

2 concentration trends closely align with actual emissions data. Cities with lower actual emissions exhibit proportionally lower simulated concentrations, reflecting the model’s ability to capture spatial variations in carbon output. This consistency validates the model’s application for assessing CO

2 emissions across the Yangtze River Delta.

4.2. Simulation of Backward Trajectories

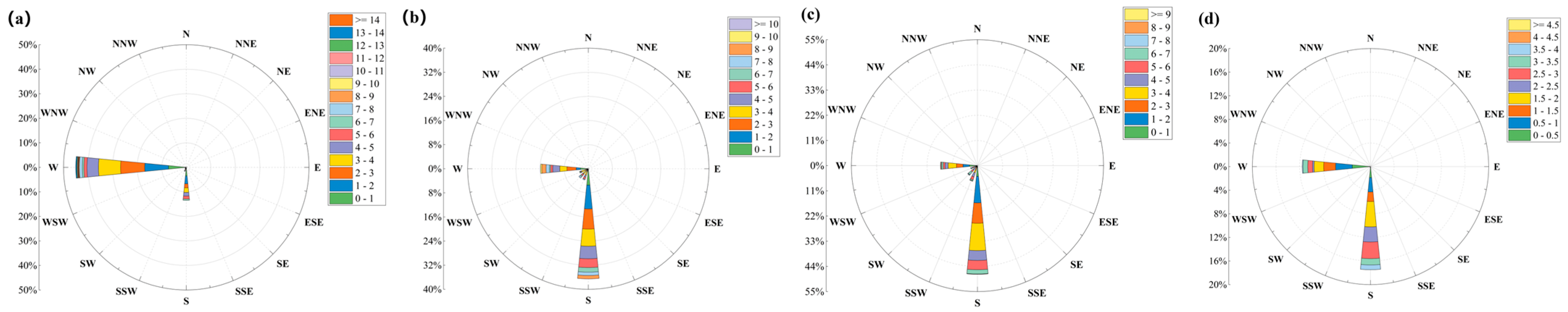

The majority of cities in the YRD are situated on the flat terrain of the region’s middle and lower river reaches, making them highly sensitive to wind direction and atmospheric flow patterns.

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate wind rose diagrams for Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Hefei across the four seasons, revealing that prevailing wind directions in the YRD vary significantly by season. Dominant wind flows are typically from the northeast, west, and south, with occasional influence from other directions (lower wind speeds).

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 depict the spatial interaction scope of CO

2 transmission among the four representative cities. Most CO

2 transmission remains contained within the YRD urban agglomeration. Coastal cities like Shanghai are influenced not only by emissions from adjacent inland cities but also by monsoonal sea breezes and other meteorological phenomena.

Table 3 quantitatively details the mutual CO

2 transmission contributions among Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Hefei. The data indicate that Shanghai and Nanjing are more significantly impacted by surrounding cities—attributable to their central locations and the frequent westward and southward wind flows. Conversely, Hangzhou, which primarily experiences northeast winds in the fall, shows a marked influence from Shanghai. Hefei, positioned further inland and with less exposure to dominant seasonal wind flows, demonstrates the lowest level of external CO

2 influence among the four cities. This is visually supported by its interaction map (

Figure 12), which is dominated by cooler tones (blue and green) and shows relatively limited areas of high interaction intensity (red zones). This minimal external impact highlights Hefei’s comparative isolation from regional CO

2 transmission effects and underscores its role as a lower-priority city in terms of cross-boundary emissions management.

4.3. Results of Two-Stage Network DEA Allocation

The two-stage network DEA model yields ideal efficiency values across both carbon generation and carbon governance stages. As depicted in

Figure 13, a significant divergence is observed between the carbon emission allowances allocated during the two phases across the 27 cities in the YRD region. Zhoushan exhibits the most dramatic discrepancy, with a 2049.98% increase in its carbon quota between the first and second stages. It also records the highest number of days with an Air Quality Index (AQI) at or above Grade 2.

As shown in

Table 4, Shanghai receives the highest allocation in both the generation and governance stages, with a total quota reaching 4.47 million tons. Suzhou ranks second in total carbon allowances. Jinhua, Shaoxing, Huzhou, and Wenzhou received similar carbon quotas in the generation stage, while Wenzhou secured a higher allocation in the treatment phase.

Substantial disparities exist in the quotas received by cities between the two stages, particularly for several cities in Anhui Province (Tongling, Maanshan, Anqing, Chuzhou, Chizhou, and Xuancheng).

At the provincial level (

Figure 14), in the generation phase, Shanghai secures the highest total quota, followed by Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui. In the governance phase, Jiangsu surpasses the other provinces, with Zhejiang following, then Shanghai and Anhui.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

In order to verify whether the model has long-lasting fitness and wide range of fitness, our study also conducts a sensitivity analysis of the model. We observe the changes in the distribution result by adjusting the parameters

,

,

,

. Box Plot (

Figure 15) shows that the target value data distribution is concentrated, with a median close to 0.3 and small fluctuations within the range of parameter changes, indicating that the model has a certain degree of stability.

Figure 16 (Parameter values vs. Objective Value) indicates that the curves for parameters α

1, α

2, γ, and ψ show significant fluctuations in the target values. α

2 fluctuates more at certain normalized values, and ψ also shows large fluctuations at some normalized values.

Figure 17 (

t-Test Results) demonstrates that the median of the t-statistic is around 2.0, and the

p-value is close to 0, indicating that the mean difference is highly statistically significant.

Figure 18 (T-Statistic for Parameters) shows that parameter ψ has the highest t-statistic (close to 3.0), followed by γ (about 2.5), α

1 (about 2.0), and α

2 (about 1.5). This suggests that when performing model tuning and optimization, the parameters ψ, γ and α

1 should be focused on to achieve the best results.

5. Discussion

This study focuses on CO2 emission rights allocation in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, and the key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

The WRF model integrated with the MEIC inventory exhibits high reliability, as simulated CO2 concentrations are highly consistent with actual emissions and effectively capture spatial variations across 27 cities. The consistency of WRF simulation results stems from the integration of high-resolution MEIC inventory data and meteorological dynamics, which overcomes the limitations of traditional emission factor methods in capturing actual emission scenarios. This accuracy is critical for subsequent inter-city transmission analysis, as CO2 dispersion is inherently tied to meteorological conditions.

- (2)

Inter-city CO2 transmission in the YRD is significantly influenced by seasonal wind patterns: Shanghai and Nanjing are more affected by surrounding cities due to their central locations and dominant wind flows, while Hefei (inland) has the weakest external CO2 impact. Most transmission is confined within the urban agglomeration, with coastal cities like Shanghai additionally influenced by marine meteorological factors. The seasonal and spatial differences in inter-city CO2 transmission are primarily driven by the YRD’s geographical and meteorological characteristics: the flat terrain of the middle and lower Yangtze River plain facilitates atmospheric transport, while seasonal wind shifts (northeast winds in winter, southwest winds in summer) reshape transmission paths. Shanghai and Nanjing’s central positions in the urban agglomeration make them “transmission hubs,” while Hefei’s inland location reduces exposure to dominant wind flows, resulting in weaker cross-city impacts.

- (3)

The two-stage DEA model reveals substantial differences in quota allocation between the generation and governance stages: Shanghai leads in total quotas due to superior economic scale and governance capacity; cities in Anhui Province (e.g., Tongling, Chuzhou) show extreme disparities between the two stages; governance performance (e.g., green patents, AQI-compliant days) is a decisive factor for second-stage quotas. The significant two-stage quota disparities reflect the dual attributes of carbon emission rights allocation: the first stage (generation) is dominated by economic and energy input-output efficiency, while the second stage (governance) emphasizes environmental management capacity. Cities like Zhoushan achieve substantial second-stage quota growth because their favorable natural conditions (fewer extreme weather events) and effective pollution control (more AQI-compliant days) compensate for modest generation-stage inputs. In contrast, Anhui’s industrial cities (e.g., Tongling, Maanshan) face lower first-stage quotas due to relatively low economic efficiency and weaker governance capacity, leading to larger inter-stage gaps.

- (4)

Sensitivity analysis confirms the model’s stability (small target value fluctuations) and identifies key sensitive parameters (ψ, γ, α1), which have significant impacts on allocation outcomes. The model’s stability and parameter sensitivity indicate that the framework balances flexibility and robustness: the small fluctuation of target values ensures consistent allocation outcomes, while the sensitivity of ψ (governance stage weight) and γ (generation stage weight) highlights the importance of balancing emission generation and management in policy design.

This study aligns with and extends international research on carbon emission rights allocation and inter-regional pollution transmission. Regarding carbon emission rights allocation, the international literature has long centered on balancing two core principles: equity (e.g., per capita allocation to protect developmental rights) and efficiency (e.g., allocating quotas based on abatement cost or productivity) [

103,

104]. Early foundational studies, such as those on the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), primarily adopted top-down allocation mechanisms based on historical emissions (grandfathering) or sectoral benchmarks [

105], but these approaches ignored spatial interdependencies between regions—a critical limitation highlighted by recent critiques [

106]. Subsequent studies attempted to integrate efficiency into allocation via Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) models [

20,

48], but most remained confined to single-stage frameworks (focusing only on emission generation efficiency) or static spatial scales (national/provincial), failing to capture dynamic inter-city spillover effects or post-emission governance capacities [

106]. For instance, Joltreau & Sommerfeld emphasized the need for urban agglomeration-scale allocation in high-density regions but did not propose a method to quantify cross-city emission transmission [

107].

Our study advances this line of research by three key contributions: (1) Unlike traditional allocation models (e.g., EU ETS grandfathering, single-stage DEA) that treat regions as independent units, we explicitly integrate inter-city CO2 spillover effects (driven by meteorological factors) into the allocation framework, addressing the “spatial blindness” of international mainstream methods; (2) We narrow the spatial scope from national/provincial (dominant in international studies) to urban agglomerations, enabling more precise quota distribution that aligns with the actual economic-environmental interaction of interconnected cities; (3) We extend the single-stage DEA to a two-stage network DEA that links emission generation (economic efficiency) and governance (environmental management capacity), resolving the long-standing trade-off between efficiency and equity in international allocation research.

The proposed framework offers multiple extension opportunities for international and regional carbon management research. The model can be replicated in other high-density urban agglomerations globally, such as the Greater Tokyo Area or the European Megalopolis. For example, in regions with complex topographical conditions, the WRF model can be adjusted to incorporate terrain effects, while the two-stage DEA can adapt to local governance indicators (e.g., EU Emissions Trading System compliance rates). International studies have begun to combine AI with carbon allocation models. This framework can be enhanced by integrating machine learning (e.g., LSTM neural networks) to predict inter-city transmission trends, or by using reinforcement learning to optimize genetic algorithm parameters (e.g., mutation rate, population size), further improving allocation accuracy.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

This study proposes a novel two-stage network DEA model integrating inter-city CO2 transmission and governance capacity for carbon emission rights allocation in the YRD urban agglomeration. The research findings carry significant implications for sustainability and environmental governance in urban agglomerations, addressing the core challenge of balancing economic growth and carbon mitigation. Cities with higher governance scores (e.g., Shanghai, Zhoushan) securing increased quotas creates a positive incentive for proactive environmental management—encouraging investments in green technology and infrastructure that reduce carbon intensity while preserving economic vitality. Additionally, the model’s consideration of inter-city CO2 transmission addresses the “collective action problem” in sustainability governance: by recognizing that emissions transcend administrative boundaries, it promotes regional synergy rather than isolated city-level efforts, which is essential for achieving carbon peaking and neutrality targets in high-density urban clusters.

Traditional policies often overemphasize historical emission levels, which disadvantages cities with weak economic bases but improving governance (e.g., Wenzhou, Zhoushan). Our model demonstrates that incorporating governance indicators into quota allocation can guide local governments to prioritize environmental management—for instance, increasing green space coverage, supporting green patent development, and strengthening air quality control. This is particularly relevant for China’s urban agglomeration governance system, as it provides a measurable tool to evaluate and incentivize local environmental performance. Furthermore, the provincial-level differences (Jiangsu and Shanghai leading in generation, Jiangsu and Zhejiang in governance) reflect the YRD’s socio-economic division of labor: Jiangsu and Shanghai are industrial and economic powerhouses with higher emission generation, while Zhejiang’s stronger governance performance stems from its earlier focus on green development (e.g., digital economy, eco-industrial parks). This pattern underscores the importance of region-specific socio-economic policies.

The research’s implications for sustainability, governance, and socio-economic development are summarized as follows.

- (1)

To promote long-term sustainability, policymakers should embed governance performance into carbon allocation policies, rewarding cities that invest in green technology, improve air quality, and enhance carbon management. This not only reduces carbon intensity but also fosters sustainable economic structures by linking quota acquisition to low-carbon development. Additionally, regional collaborative mechanisms should be established to address inter-city emission transmission, such as joint monitoring of wind-driven CO2 flow and shared emission reduction targets, ensuring that sustainability efforts are not undermined by spatial spillover effects.

- (2)

To mitigate socio-economic disparities, targeted support should be provided to cities with weak governance capacity but high development potential (e.g., Anhui’s industrial cities). This could include financial subsidies for environmental protection investment, technical training for green patent development, and cross-city partnerships to share best practices in air quality management. By reducing the governance gap, these cities can better participate in the carbon trading system, avoiding excessive emission reduction pressure that threatens employment and industrial upgrading. Furthermore, the model’s parameter flexibility (e.g., GDP protection coefficient) allows policymakers to adjust the balance between economic growth and environmental protection according to regional socio-economic conditions, ensuring that allocation policies are inclusive and adaptable.

- (3)

The YRD’s socio-economic diversity—with eastern cities leading in economic scale and western cities in development potential—should be leveraged to optimize carbon allocation. Eastern hubs (Shanghai, Suzhou) can focus on technological innovation and green infrastructure to maintain high governance performance, while central and western cities (Hefei, Anqing) can prioritize industrial restructuring and governance capacity building to improve their quota competitiveness. This division of labor promotes regional synergy, as eastern cities can transfer green technology and capital to western cities, while western cities contribute to regional emission reduction through improved governance, creating a win-win for socio-economic development and environmental protection.

There are still several deficiencies in the study that require future attention. Firstly, the contribution of the cities concerned. While previous studies often utilize generic urban scenarios to represent provinces and cities, the WRF-chem model offers a more accurate depiction of the interconnections between individual cities. This enables a more customized allocation that aligns with each city’s unique circumstances. Secondly, the efficacy of CO2 control can be assessed from other perspectives. Hence, in the future, the choice of metrics to evaluate the efficacy of governance can be more all-encompassing. Furthermore, the use of 2020 data, while facilitating high-resolution simulation of CO2 transmission, is affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to short-term anomalies in absolute emission levels. Although the model’s focus on structural factors (spatial spillover, governance capacity) mitigates this impact, future research should validate the framework with data from non-pandemic years (e.g., 2019, 2021) to further confirm the generalizability of the allocation results. Additionally, the integration of multi-year average data could reduce the impact of single-year anomalies and improve the long-term guiding significance of the allocation scheme.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T., J.C. and M.T.; Methodology, J.C., C.H., M.T. and P.L.; Validation, L.M.; Formal analysis, M.T.; Investigation, L.M.; Writing—original draft, L.M.; Writing—review & editing, M.T.; Visualization, P.L.; Supervision, M.T., J.C., C.H. and M.T.; Project administration, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 72474128, 72504166, 72304161; The Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 24&ZD042; Shanghai 2025 Soft Science Research Project Foundation, grant numbers 25692110000, 25692108800; Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China, grant numbers ZR2022QG029, ZR2023QG066.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, Z.; Xia, C.; Fang, K.; Zhang, W. Effect of the carbon emissions trading policy on the co-benefits of carbon emissions reduction and air pollution control. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Khishgee, S.; Alimujiang, A.; Dong, H. Cost-effective approaches for reducing carbon and air pollution emissions in the power industry in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.-H.; He, L.-Y. Study on the synergistic effect of air pollution prevention and carbon emission reduction in the context of “dual carbon”: Evidence from China’s transport sector. Energy Policy 2023, 173, 113370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Lu, J.; Luo, X.; Ge, J. Carbon emission evaluation model and carbon reduction strategies for newly urbanized areas. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Qi, J.; Schandl, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, S. Scarcity-weighted fossil fuel footprint of China at the provincial level. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Lv, K.; Han, C.; Liu, P. Trading behavior strategy of power plants and the grid under renewable portfolio standards in China: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Energy 2023, 284, 128398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Sun, R. Effectiveness of China’s provincial industrial carbon emission reduction and optimization of carbon emission reduction paths in “lagging regions”: Efficiency-cost analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 275, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Ye, P. A more scientific allocation scheme of carbon dioxide emissions allowances: The case from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J. Allocation of carbon emission quotas in China’s provincial power sector based on entropy method and ZSG-DEA. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yang, J.; Zhong, F. Carbon emission quotas and a reduction incentive scheme integrating carbon sinks for China’s provinces: An equity perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 41, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. A performance analysis framework for carbon emission quota allocation schemes in China: Perspectives from economics and energy conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wu, F.P.; Chen, L.X. Harmonious allocation of carbon emission permits based on dynamic multiattribute decision-making method. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, B. A comparative analysis of Chinese provincial carbon dioxide emissions allowances allocation schemes in 2030: An egalitarian perspective. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 765, 142705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Xie, R.; Lu, Y.; Fang, J.; Liu, Y. The effects of urban agglomeration economies on carbon emissions: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Sun, K.; Li, L.; Lei, Y.; Wu, S.; Tang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Spatiotemporal pattern analysis of PM2.5 and the driving factors in the middle Yellow River urban agglomerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cai, W.; Ma, M.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Li, L.; Chen, X. Driving forces of China’s CO2 emissions from energy consumption based on Kaya-LMDI methods. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 711, 134569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, H.; Wu, W.; Chen, L. A multi-level characteristic analysis of urban agglomeration energy-related carbon emission: A case study of the Pearl River Delta. Energy 2023, 263, 125651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, H.; Liang, D.; Chen, Y.; Tian, P.; Xia, J.; Wang, H.; Lei, X. Ecological sustainability and its driving factor of urban agglomerations in the Yangtze River Economic Belt based on three-dimensional ecological footprint analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, X. The impact of urban agglomeration on ozone precursor conditions: A systematic investigation across global agglomerations utilizing multi-source geospatial datasets. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 704, 135458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Qu, J.; Li, A.; Liu, X. A new approach for evaluating technology inequality and diffusion barriers: The concept of efficiency Gini coefficient and its application in Chinese provinces. Energy 2021, 235, 121256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Hu, Y.-J.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Regional allowance allocation in China based on equity and efficiency towards achieving the carbon neutrality target: A composite indicator approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 342, 130914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Hao, X.; Song, M.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, B. Carbon emission performance and quota allocation in the Bohai Rim Economic Circle. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Cui, X. Two-step allocation of CO2 emission quotas in China based on multi-principles: Going regional to provincial. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-H.; Lu, K.-F.; Peng, Z.-R.; He, H.-D.; Xu, S.-Q. Spatiotemporal variations of carbon dioxide (CO2) at Urban neighborhood scale: Characterization of distribution patterns and contributions of emission sources. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Xu, X.; Liao, D.; Ji, X.; Hong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Air pollution increases human health risks of PM2.5-bound PAHs and nitro-PAHs in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 770, 145402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, H. A multi-criteria decision analysis model for carbon emission quota allocation in China’s east coastal areas: Efficiency and equity. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Wan, Q.; Lou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W. Green fiscal policy and firms’ investment efficiency: New insights into firm-level panel data from the renewable energy industry in China. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shi, Z.; Han, D.; Zeng, J. Agglomeration of the new energy industry and green innovation efficiency: Does the spatial mismatch of R&D resources matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, W.; Ning, Z. Carbon reduction and cost control of container shipping in response to the European Union Emission Trading System. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 21172–21188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Huo, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B. Marginal abatement cost under the constraint of carbon emission reduction targets: An empirical analysis for different regions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.; Fei, R.; Jiang, H.; Cui, L.; Zhu, Y. How can China achieve its goal of peaking carbon emissions at minimal cost? A research perspective from shadow price and optimal allocation of carbon emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pardo, F.; Pérez-Moreno, S.; Bárcena-Martín, E. Leaving no Country Behind: A Fuzzy Approach for Human Development. J. Human Dev. Capab. 2022, 23, 572–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, M. Carbon dioxide emissions allocation: A review. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.; Chen, Z. Evaluation and selection of sustainable hydrogen production technology with hybrid uncertain sustainability indicators based on rough-fuzzy BWM-DEA. Renew. Energy 2021, 165, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, S.; Brunner, J.O. Benchmarking the benchmarks—Comparing the accuracy of Data Envelopment Analysis models in constant returns to scale settings. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 285, 1042–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.-M. DEA target setting approach within the cross efficiency framework. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 96, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Guo, W.; Xiong, X.; Guan, Z. A hybrid approach combining data envelopment analysis and recurrent neural network for predicting the efficiency of research institutions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, B. Energy and CO2 emission performance: A regional comparison of China’s non-ferrous metals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, W.; He, Y.; Dong, J. Spill-over effect and efficiency of seven pilot carbon emissions trading exchanges in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 838, 156020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, J.; Long, H.; Xiong, X.; Wu, D. A ZSG-DEA model with factor constraint cone-based decoupling analysis for household CO2 emissions: A case study on Sichuan province. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 93269–93284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, M.R.; Mohammadi, S.; Wanke, P.F.; Correa, H.L. Towards greener petrochemical production: Two-stage network data envelopment analysis in a fully fuzzy environment in the presence of undesirable outputs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 164, 113903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Angulo-Meza, L.; González-Araya, M.C.; Iriarte, A.; Vásquez-Ibarra, L.; Rengel, F.M. A new method for eco-efficiency assessment using carbon footprint and network data envelopment analysis applied to a beekeeping case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wei, Q.; Li, A.; Chen, S. A new intermediate network data envelopment analysis model for evaluating China’s sus-tainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Triantis, K.; Murray-Tuite, P.; Edara, P. Performance measurement of a transportation network with a downtown space reservation system: A network-DEA approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 1140–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y. Evaluation of green low-carbon innovation development efficiency: An improved two-stage non-cooperative DEA model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayir Ervural, B.; Zaim, S.; Delen, D. A two-stage analytical approach to assess sustainable energy efficiency. Energy 2018, 164, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Han, C.; Hu, S. A two-stage chance constrained stochastic programming model for emergency supply distribution considering dynamic uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 179, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Ang, S.; Yang, F. Performance evaluation of two-stage network structures with fixed-sum outputs: An application to the 2018winter Olympic Games. Omega 2021, 102, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Niu, A.; Lin, C. Optimizing carbon emission forecast for modelling China’s 2030 provincial carbon emission quota allocation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, P. Unveiling the driving factors of carbon emissions from industrial resource allocation in China: A spatial econometric perspective. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Chu, C.; Zhang, L.L.; Yu, Y. Optimizing an emission trading scheme for local governments: A Stackelberg game model and hybrid algorithm. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wen, S.; Sun, Z. Current relationship between coal consumption and the economic development and China’s future carbon mitigation policies. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wei, Y.-M.; Wang, K. Provincial allocation of carbon emission reduction targets in China: An approach based on improved fuzzy cluster and Shapley value decomposition. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ni, G. Decomposing capacity utilization under carbon dioxide emissions reduction constraints in data envelopment analysis: An application to Chinese regions. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Ye, F.; Zhang, L. Carbon dioxide emissions quotas allocation in the Pearl River Delta region: Evidence from the maximum deviation method. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, J.; Dong, Z.Y. A real-time carbon emission estimation framework for industrial parks with non-intrusive load monitoring. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, V.; Clain, P.; Fournaison, L.; Delahaye, A. Experimental monitoring of CO2 hydrate slurry crystallization by heat flux rate determination in a jacketed reactor. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 217, 124665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballav, S.; Naja, M.; Patra, P.K.; Machida, T.; Mukai, H. Assessment of spatio-temporal distribution of CO2 over greater Asia using the WRF–CO2 model. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 129, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xiu, A.; Zhang, X.; Tong, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Zhang, M. Two-way coupled meteorology and air quality models in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of impacts of aerosol feedbacks on meteorology and air quality. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 5265–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Jiang, F.; Feng, S.; Xia, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lyu, X.; Zhang, L.; Lou, C. Increased diurnal difference of NO2 concentrations and its impact on recent ozone pollution in eastern China in summer. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 858, 159767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Gong, W.; Hong, J.; Jin, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B. Aerosol optical properties of haze episodes in eastern China based on remote-sensing observations and WRF-Chem simulations. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 757, 143784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Gao, C.; Song, K.; Gao, W.; Guo, Y.; Gao, C. The changes in spatial layout of steel industry in China and associated pollutant emissions: A case of SO2. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bei, N.; Tie, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, R.; Li, G. Local and transboundary transport contributions to the wintertime par-ticulate pollution in the Guanzhong Basin (GZB), China: A case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 148876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Zhu, Y.; Jang, J.; Wang, S.; Xing, J.; Chiang, P.-C.; Fan, S.; You, Z.; Li, J. Real-time source contribution analysis of ambient ozone using an enhanced meta-modeling approach over the Pearl River Delta Region of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, F.; Jia, M.; Feng, S.; Lai, Y.; Ding, J.; He, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Improved estimation of CO2 emissions from thermal power plants based on OCO-2 XCO2 retrieval using inline plume simulation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 913, 169586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhan, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Fu, P.; Huang, F.; Lai, J.; Chen, J.; Hong, F.; et al. Satellite-based mapping of the Universal Thermal Climate Index over the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Liang, H.; Dong, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, G. Synergistic CO2 reduction effects in Chinese urban agglomerations: Perspectives from social network analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 798, 149352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, W. Spatial structure and carbon emission of urban agglomerations: Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving forces. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Xie, M. Exploring the link between ozone pollution and stratospheric intrusion under the influence of tropical cyclone Ampil. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 828, 154261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q. MeteoInfo: GIS software for meteorological data visualization and analysis. Meteorol. Appl. 2014, 21, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, H.; Geng, G.; Hong, C.; Liu, F.; Song, Y.; Tong, D.; Zheng, B.; Cui, H.; Man, H.; et al. Anthropogenic emission inventories in China: A review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 834–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Meteorological Administration. China Climate Bulletin 2021; National Climate Center: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Guo, J.; Zhao, M.; Wu, X.; Shi, B.; Gonzalez, E.D.S. Study on the distribution of PM emission rights in various provinces of China based on a new efficiency and equity two-objective DEA model. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Geng, Y.; Sheng, J. Efficient allocation of CO2 emissions in China: A zero sum gains data envelopment model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4144–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Guo, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z. Study on the Allocation of SO2 Emission Rights in the Yangtze River Delta City Agglomeration Region of China Based on Efficiency and Feasibility. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. The comprehensive environmental efficiency analysis based on a new data envelopment analysis: The super slack based measure network three-stage data envelopment analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yu, S.; Wu, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, L. Carbon emissions prediction considering environment protection investment of 30 provinces in China. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ciais, P.; Zeng, Z.; Cescatti, A.; Shang, J.; Chen, J.M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.-P.; Yuan, W.; et al. Asymmetric influence of forest cover gain and loss on land surface temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S.I.; Ahmad, M.; Haq, Z.U.; Shaofu, G.; Hang, J. On the goals of sustainable production and the conditions of environmental sustainability: Does cyclical innovation in green and sustainable technologies determine carbon dioxide emissions in G-7 economies. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y.; Liang, X.; Jia, H.; Liu, L. How Extreme Events in China Would Be Affected by Global Warming—Insights From a Bias-Corrected CMIP6 Ensemble. Earth’s Futur. 2023, 11, e2022EF003347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Peng, L. Analysis of driving factors and allocation of carbon emission allowance in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 673, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, R.; Wen, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Hao, J. Impact of labor and energy allocation imbalance on carbon emission efficiency in China’s industrial sectors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tang, J.; Huang, F. The impact of industrial structure adjustment on the spatial industrial linkage of carbon emission: From the perspective of climate change mitigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, Y. How does public concern about climate change affect carbon emissions? Evidence from large-scale online content and provincial-level data in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D.; Pian, Q. Continuous allocation of carbon emission quota considering different paths to carbon peak: Based on multi-objective optimization. Energy Policy 2023, 178, 113622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jian, X.; Wang, H.; Jahanger, A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Unraveling the nexus: China’s economic policy uncertainty and carbon emission efficiency through advanced multivariate quantile-on-quantile regression analysis. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, G.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, C. Two-stage DEA models with fairness concern: Modelling and computational aspects. Omega 2021, 105, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-T. Restricting weight flexibility in fuzzy two-stage DEA. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 74, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S. Efficiency decomposition of the network DEA in variable returns to scale: An additive dissection in losses. Omega 2021, 100, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günel, K. Weighted Centroids in Adaptive Nelder–Mead Simplex: With heat source locator and multiple myeloma predictor applications. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 151, 111178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandavi, S.M.; Chung, V.Y.Y.; Anaissi, A. Stochastic Dual Simplex Algorithm: A Novel Heuristic Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 2725–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Fan, L.; Kong, T.; Wu, Y. A fast end-to-end method for automatic interior progress evaluation using panoramic images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Dai, F.-A. A Warm-Start Strategy in Interior Point Methods for Shrinking Horizon Model Predictive Control With Variable Discretization Step. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2023, 68, 3830–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Ge, H.; Wang, X.; Yan, W.; Han, C. Optimization of ship routing and allocation in a container transport network considering port congestion: A variational inequality model. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 244, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, E.C. Multi-Objective Optimization by Using Evolutionary Algorithms: The p-Optimality Criteria. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2014, 18, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, S.Y.; Chow, C.K. A Genetic Algorithm That Adaptively Mutates and Never Revisits. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çilingir, F. The boundless area of perturbed map generated by using relaxed Newton’s method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhao, X.; Deng, F. Incremental Newton’s iterative algorithm for optimal control of Itô stochastic systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 421, 126958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zeng, K. Communication-Aware Secret Share Placement in Hierarchical Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 3717–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushaba, R.N.; Al-Ani, A.; Al-Jumaily, A. Feature subset selection using differential evolution and a statistical repair mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 11515–11526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryvkin, D. The selection efficiency of tournaments. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 206, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, M. Parent Selection Pressure Auto-Tuning for Tournament Selection in Genetic Programming. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2013, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Allocating and Distributing Emission Allowances: Principles and Practice. In OECD Environmental Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; No. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman, A.D.; Buchner, B.K. The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme: Origins, Allocation, and Early Results. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2007, 1, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerman, A.D.; Convery, F.J.; de Perthuis, C. Pricing carbon in Europe: The EU ETS experience. J. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 24, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Barcena-Martin, E.; Garcia-Pardo, F. An axiomatic approach to measure the ‘Leave no one behind’ principle. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2022, 447, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joltreau, J.; Sommerfeld, K. Carbon emission rights allocation in urban agglomerations: A review of methods and chal-lenges. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51, 101752. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Study area overview map.

Figure 1.

Study area overview map.

Figure 2.

Research framework of the two-stage network DEA model for carbon emission rights allocation.

Figure 2.

Research framework of the two-stage network DEA model for carbon emission rights allocation.

Figure 3.

Network DEA under the influence of atmospheric transport.

Figure 3.

Network DEA under the influence of atmospheric transport.

Figure 4.

Validation of the relevance of WRF simulation results. The letters in the horizontal coordinates in

Figure 4 represent the abbreviation of the name of each city. The left vertical coordinate is the one-month CO

2 emission concentration modeled in the WRF, and the right vertical coordinate is the actual CO

2 emissions.

Figure 4.

Validation of the relevance of WRF simulation results. The letters in the horizontal coordinates in

Figure 4 represent the abbreviation of the name of each city. The left vertical coordinate is the one-month CO

2 emission concentration modeled in the WRF, and the right vertical coordinate is the actual CO

2 emissions.

Figure 5.

Shanghai Seasonal Wind Map. The four subgraphs (a–d) correspond to winter, spring, summer, and autumn, respectively. The radial direction indicates wind direction (e.g., NNW = north-northwest, SSE = south-southeast), and the percentage labels represent the frequency of each wind direction.

Figure 5.

Shanghai Seasonal Wind Map. The four subgraphs (a–d) correspond to winter, spring, summer, and autumn, respectively. The radial direction indicates wind direction (e.g., NNW = north-northwest, SSE = south-southeast), and the percentage labels represent the frequency of each wind direction.

Figure 6.

Hangzhou Seasonal Wind Map. The four subgraphs (a–d) correspond to winter, spring, summer, and autumn, respectively.

Figure 6.