Rice–Fish Integration as a Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods Among Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from DPSIR-Informed Analysis in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

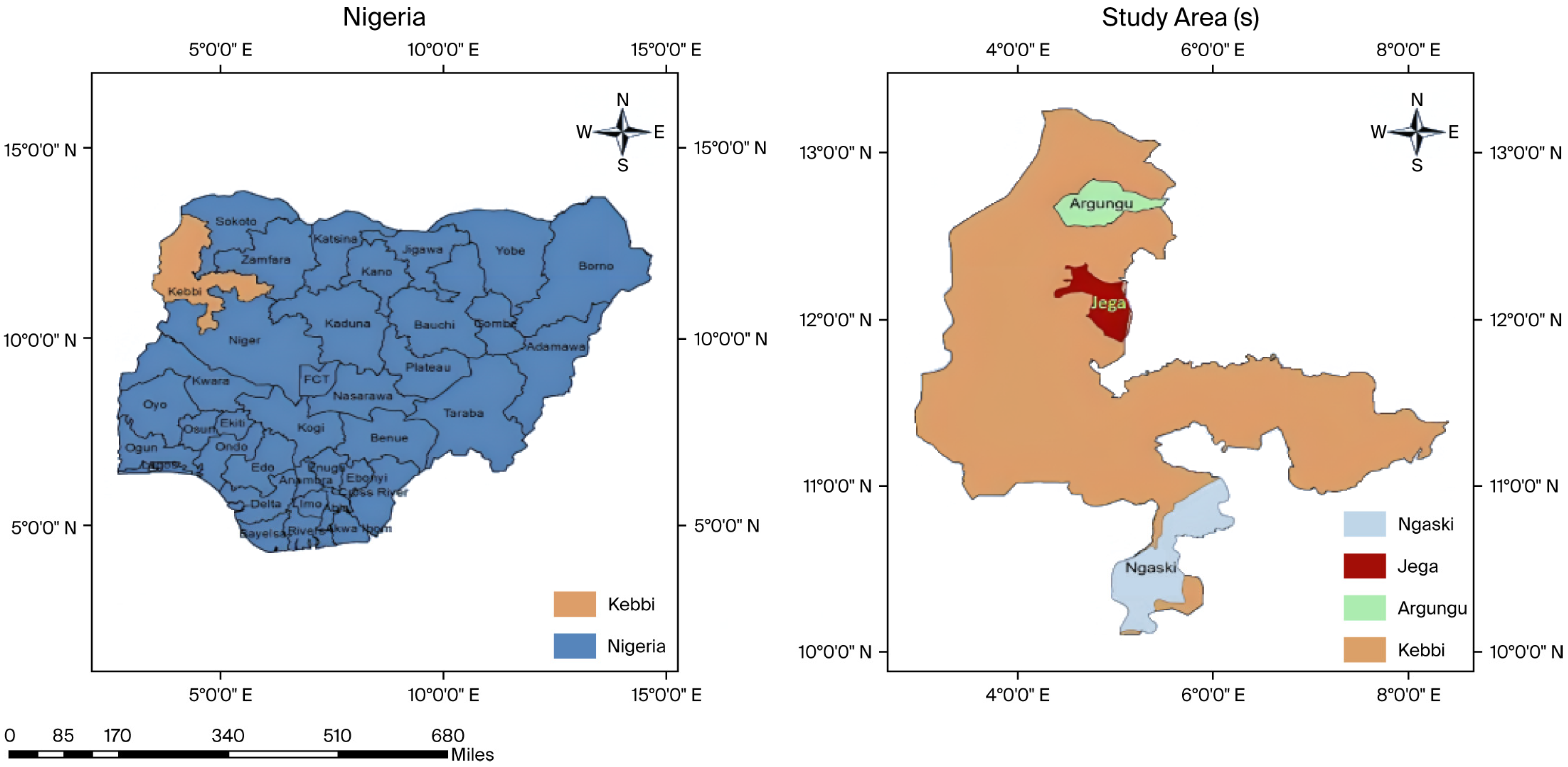

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Survey Instrument Design

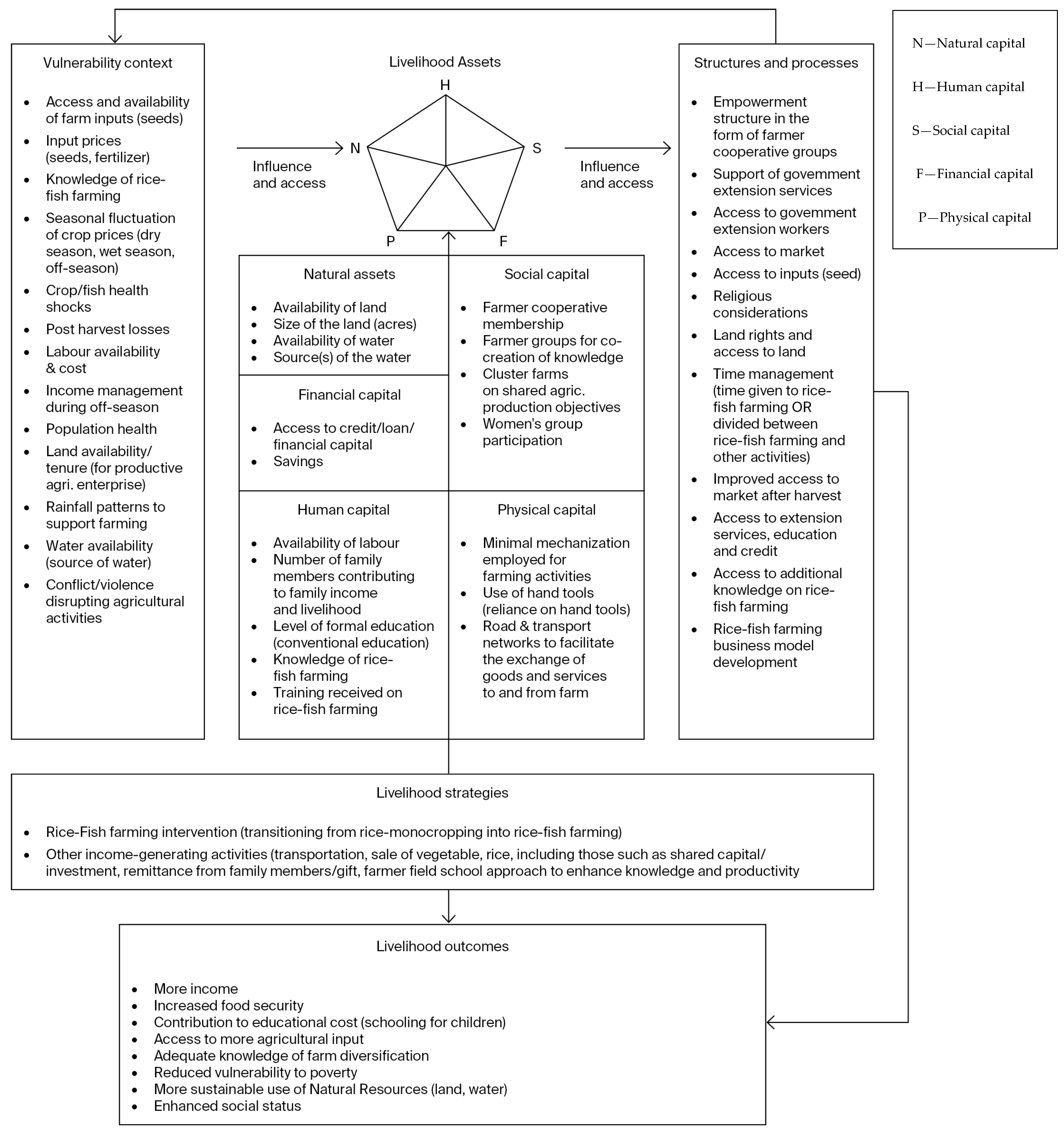

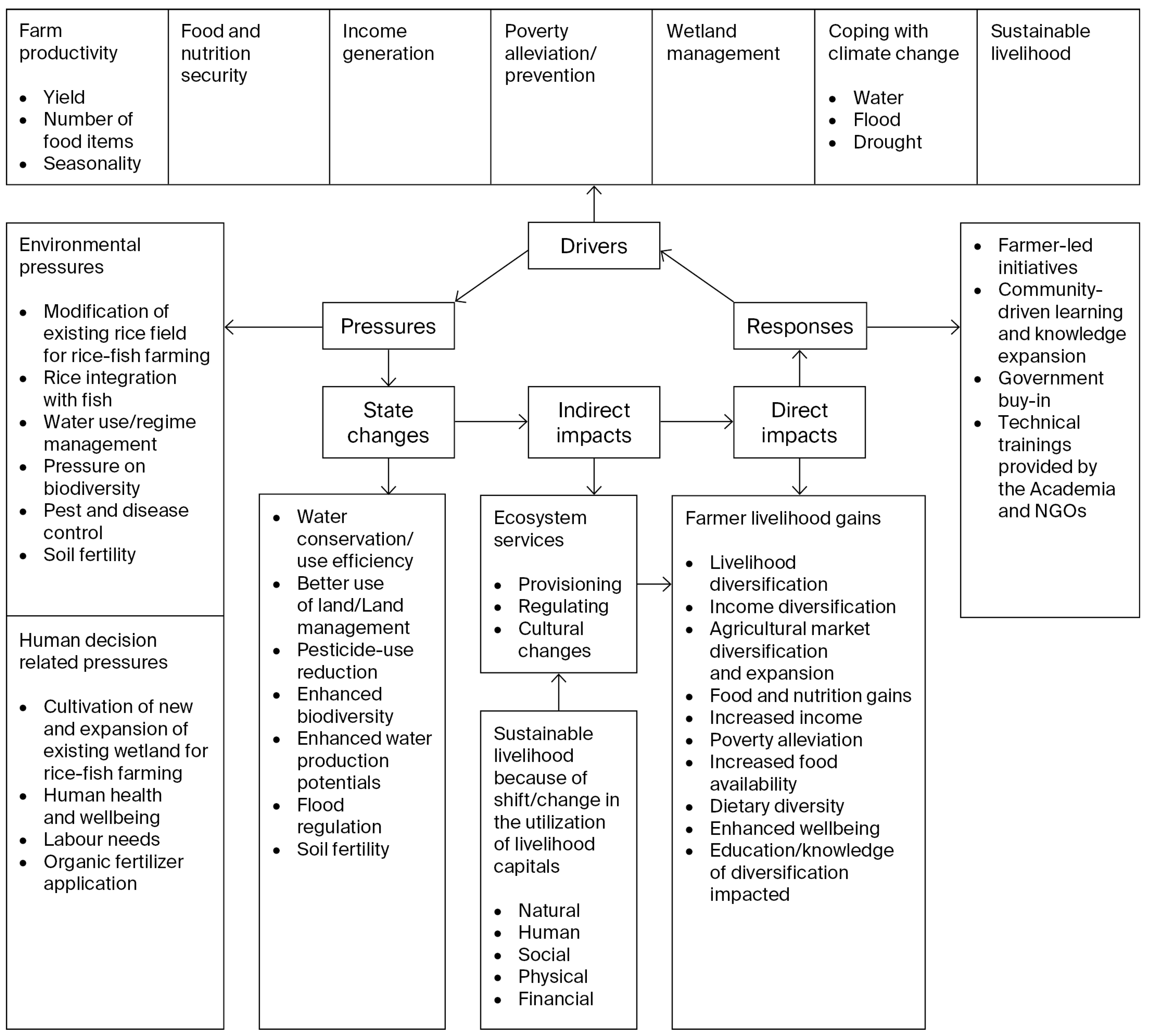

2.2.2. Measurement of Variables from SLF and DPSIR Frameworks

2.3. Sampling and Sample Size

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of Rice–Fish Farmers

3.2. Livelihood Capitals of Rice Farmers for Adopting Rice–Fish Farming

3.2.1. Natural Capital

3.2.2. Human Capital

3.2.3. Financial Capital

3.2.4. Social and Physical Capitals

3.3. Vulnerability Context Limiting Sustainable Livelihoods

3.4. Livelihood Structures and Processes Linked to Rice–Fish Farming

3.5. Livelihood Strategies of Rice Farmers

3.6. Livelihood Outcomes

3.7. Regression Analysis of Livelihood Predictors

4. Discussion

4.1. Livelihood Strategies and Vulnerability Management

4.2. Livelihood Management

4.3. Livelihood Outcomes

4.4. Factors Influencing Adoption and Performance

4.5. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mauki, C.; Jeckoniah, J.; Massawe, G.D. Smallholder Rice Farmers Profitability in Agricultural Marketing Co-Operative Societies in Tanzania: A Case of Mvomero and Mbarali Districts. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouna, A.; Fatognon, I.A.; Saito, K.; Futakuchi, K. Moving toward Rice Self-Sufficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030: Lessons Learned from 10 Years of the Coalition for African Rice Development. World Dev. Perspect. 2021, 21, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zewdu, Z.; Dessie, A.; Atinaf, M.; Berie, A.; Bitew, M.; Abdi, G. Evaluation of Yield and Yield Components of Lowland Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Varieties in the Rainfed-Lowland Rice Producing Areas of Ethiopia. Acad. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2019, 7, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg, J.; Saito, K. Towards Sustainable Productivity Enhancement of Rice-Based Farming Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Field Crops Res. 2022, 287, 108670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamayevu, D.; Nyagumbo, I.; Chiduwa, M.; Liang, W.; Li, R. Understanding Crop Diversification Among Smallholder Farmers: Socioeconomic Insights from Central Malawi. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loko, Y.L.E.; Gbemavo, C.D.S.J.; Djedatin, G.; Ewedje, E.-E.; Orobiyi, A.; Toffa, J.; Tchakpa, C.; Sedah, P.; Sabot, F. Characterization of Rice Farming Systems, Production Constraints and Determinants of Adoption of Improved Varieties by Smallholder Farmers of the Republic of Benin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper No. 72; Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Apine, E.; Turner, L.M.; Rodwell, L.D.; Bhatta, R. The Application of the Sustainable Livelihood Approach to Small Scale-Fisheries: The Case of Mud Crab Scylla Serrata in South West India. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 170, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, S.; Barman, B.; Dubois, M.; Flor, R.J.; Funge-Smith, S.; Gregory, R.; Hadi, B.A.R.; Halwart, M.; Haque, M.; Jagadish, S.V.K.; et al. Maintaining Diversity of Integrated Rice and Fish Production Confers Adaptability of Food Systems to Global Change. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 576179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Phonexay, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Status of Rice-Fish Farming and Rice Field Fisheries in Northern Laos. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1174172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, C.; Guo, Z.; Guo, Y.; Cao, C. Sustainability of the Rice–Crayfish Farming Model in Waterlogged Land: A Case Study in Qianjiang County, Hubei Province, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpoffo, A.M.Y.; Kouadio, K.S.A.; Yeo, Y.A.; Dossou-Yovo, E.R. Adoption Levels, Barriers, and Incentive Mechanisms for Scaling Integrated Rice-Fish System and Alternate Wetting and Drying in Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria; Africa Rice Center: Bouake, Cote d’Ivoire, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Awuor, F.J.; Macharia, I.N.; Mulwa, R.M. Adoption and Intensity of Integrated Agriculture Aquaculture among Smallholder Fish Farmers in Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1181502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, J. Rice–Fish Integration in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Challenges for Participatory Water Management. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2015, 49, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Tracking Progress on Food and Agriculture-Related SDG Indicators 2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 978-92-5-139913-2. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Making Food Systems Work for People and Planet UN Food Systems Summit +2; Report of the Secretary-General; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Tracking Progress on Food and Agriculture-Related SDG Indicators 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136737-7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Dai, R.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, T.; Ye, J.; Tang, J.; Hu, L.; Chen, X. Traditional Rice-Fish System Benefits Sustainable Production of Small Farms and Conservation of Local Resources. Agric. Syst. 2025, 228, 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.H.P.; Long, T.X.; Da, C.T.; Tam, N.T.; Berg, H. Drivers and Barriers for Adopting Rice–Fish Farming in the Hau Giang Province of the Mekong Delta. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departement for International Development (DFID). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; DFID: London, UK, 1999; Section 2.1. [Google Scholar]

- Palys, T. Purposive Sampling; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The Importance of the Normality Assumption in Large Public Health Data Sets. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, M.A.; Tripathy, S.P.; Pawale, S.S.; Bhawalkar, J.S. A Narrative Review with a Step-by-Step Guide to R Software for Clinicians: Navigating Medical Data Analysis in Cancer Research. Cancer Res. Stat. Treat. 2024, 7, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balana, B.B.; Oyeyemi, M.A. Agricultural Credit Constraints in Smallholder Farming in Developing Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. World Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Hornbuckle, J.; Turchini, G.M. Blue–Green Water Utilization in Rice–Fish Cultivation towards Sustainable Food Production. Ambio 2022, 51, 1933–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldan, B.; Janoušková, S.; Hák, T. How to Understand and Measure Environmental Sustainability: Indicators and Targets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Integrated Pest Management (IPM): An Ecosystem Approach to Crop Production and Protection. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/agriculture/crops/thematic-sitemap/theme/pests/ipm/en (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- FAO. Farmers Taking the Lead: Thirty Years of Farmer Field Schools; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Farmer Field School Guidance Document: Planning for Quality Programmes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dedehayir, O.; Ortt, R.J.; Riverola, C.; Miralles, F. Innovators and Early Adopters in the Diffusion of Innovations: A Literature Review. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1740010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, G.; Xu, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Nie, Z.; Murekezi, P.; Liang, X.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, X. Aquaculture PPP Development in China-Case Study from Hani Terrace. Mar. Policy 2024, 163, 106075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwart, M.; Gupta, M.V. (Eds.) Culture of Fish in Rice Fields; FAO: Rome, Italy; WorldFish Center: Penang, Malaysia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Shaffril, H.A.; Abu Samah, A.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Ahmad, N.; Tangang, F.; Ahmad Sidique, S.F.; Abdul Rahman, H.; Burhan, N.A.S.; Arif Shah, J.; Amiera Khalid, N. Diversification of Agriculture Practices as a Response to Climate Change Impacts among Farmers in Low-Income Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Clim. Serv. 2024, 35, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) Programme. Rice-Fish Culture, Qingtian County, China; Case Study; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. The Determinants of Rural Livelihood Diversification in Developing Countries. J. Agric. Econ. 2000, 51, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwart, M. Biodiversity and Nutrition in Rice-Based Aquatic Ecosystems. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwart, M. Valuing Aquatic Biodiversity in Agricultural Landscapes. In Diversifying Food and Diets: Using Agricultural Biodiversity to Improve Nutrition and Health; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halwart, M.; Bartley, D. (Eds.) Aquatic Biodiversity in Rice-Based Ecosystems. In Aquatic Biodiversity in Rice-Based Ecosystems: Studies and Reports from Indonesia, Lao PDR and the Philippines; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Garaway, C.J.; Photitay, C.; Roger, K.; Khamsivilay, L.; Halwart, M. Biodiversity and Nutrition in Rice-Based Ecosystems; the Case of Lao PDR. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, T.J.; Kepple, A.W.; Cafiero, C. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Developing a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide; Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/29506589-c91c-44aa-b628-b032ea38f691/content (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Rasowo, J.; Auma, E.; Ssanyu, G.; Ndunguru, M. Does African Catfish (Clarias Gariepinus) Affect Rice in Integrated Rice-Fish Culture in Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya? Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fertin, L.; Perinelle, A.; Bakker, T. From Pond to Lowland Scale, a Systemic Approach to Better Understanding Small-Scale Rice-Fish Farming Dynamics: Case Study in Guinea. Agric. Syst. 2025, 228, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oben, B.O.; Molua, E.L.; Oben, P.M. Profitability of Small-Scale Integrated Fish-Rice-Poultry Farms in Cameroon. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, B.; Bogard, J.R.; Dizyee, K.; Lim-Camacho, L.; Kumar, S. Value Chains and Diet Quality: A Review of Impact Pathways and Intervention Strategies. Agriculture 2019, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, R.H.; Nhan, D.K.; Udo, H.M.J.; Kaymak, U. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Adoption of Integrated Rice–Fish Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Rev. Aquac. 2012, 4, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, X. Review of Rice–Fish-Farming Systems in China—One of the Globally Important Ingenious Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Aquaculture 2006, 260, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Editorial: Human Capital and Human Capability. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1959–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafwila Kinkela, P.; Kambashi Mutiaka, B.; Dochain, D.; Rollin, X.; Mafwila, J.; Bindelle, J. Smallholders’ Practices of Integrated Agriculture Aquaculture System in Peri-Urban and Rural Areas in Sub Saharan Africa. Tropicultura 2019, 4, 2295–8010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, A. Direct Seeded Rice: Prospects, Problems/Constraints and Researchable Issues in India. Curr. Agric. Res. J. 2017, 5, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornlund, V.; Bjornlund, H.; van Rooyen, A. Why Food Insecurity Persists in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Existing Evidence. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean/% (±SD) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 41.26 (±9.4) | Predominantly middle-aged |

| Gender (male) | 92.14% | Female = 7.86% |

| Household size | 10.28 (±3.1) | Large, extended households |

| Indicator | Measurement | Value |

|---|---|---|

| A. Natural Capital | ||

| Land access | Yes/No | 95.2% yes, 4.8% no |

| Land ownership | Personal/Not owned/Community-owned | 86.03% personal; 10.04% not owned; 3.93% community-owned |

| Mode of land access | Inherited/Rented/Purchased/Gift/ Borrowed/Community/Joint/Other | 67.69% inherited; 11.35% rented; 10.92% purchased; 5.68% gift; 1.75% borrowed; 1.31% community; 0.87% joint; 0.44% other |

| Farm size distribution | <1 acre/1 acre/2 acres/3 acres/ 4 acres/≥5 acres | 33.19% < 1 acre; 29.69% = 1 acre; 16.16% = 2 acres; 7.86% = 3 acres; 6.11% = 4 acres; 6.55% ≥ 5 acres |

| Access to more land | Yes/No | 68.12% yes; 31.88% No |

| Water access | Yes/No | 89.52% yes; 10.48% No |

| Water sources | Rivers, tube wells, rainfall, groundwater, boreholes, reservoirs, lakes | 55.46% rivers; 49.34% tube wells; 44.54% rainfall; 30.57% groundwater; 10.40% borehole; 5.34% irrigation; 1.75% reservoir; 1.75% lake; 0.44% other |

| B. Human Capital | ||

| Labor availability | Yes/No | 94.76% yes, 4.8% no |

| Ability to afford additional labor | Yes/No | 65.07% yes, 34.93% no |

| Rice–fish knowledge before adoption | Adequate/inadequate | 46.72% adequate; 51.09% inadequate |

| Access to healthcare | Yes/No | 70.31% yes, 29.69% no |

| Knowledge gains | Rice only/Aquaculture only/Both | 58.52% rice, 22.71% aquaculture, 22.27% both |

| Adoption of flood control adaptations | Plastic lining, channels, bund elevation | Qualitative (present in text) |

| C. Financial Capital | ||

| Main income source | Sale of stored crops | 58.08% |

| Access to savings | Yes | 55.02% |

| Access to loans | Yes/No | 23.14% Yes, 76.86% no |

| Access to remittances | Yes | 10.92% |

| Casual labor during lean periods | % | 20.09% |

| D. Social Capital | ||

| Cooperative membership | Yes/no | Present (qualitatively reported) |

| Cluster farming/peer learning | Yes/No | Present in Argungu and Wawu |

| Participation in training | % reached by extension | 85.59% |

| Ownership of farming tools | Farm tools ownership | Widely owned (reported qualitatively) |

| E. Physical Capital | ||

| Access to mechanization | Yes/no | Low mechanization (reported qualitatively) |

| Road condition | Good/poor | Predominantly poor (reported qualitatively) |

| Field modifications | Ditches/Bunds/Ponds/None/Other | 41.92% ditches; 31.00% bunds; 17.47% ponds; 8.30% none; 1.31% other |

| F. Vulnerability Factors | ||

| High input prices | Yes/no | Present (reported qualitatively) |

| Fluctuating crop prices | Yes/no | Present (reported qualitatively) |

| Post-harvest losses | Yes/no | 18.78% yes; 81.22% no |

| Pesticide/herbicide use | Yes/no | 60.26% yes; 39.74% no |

| Flooding | % affected | 50.22% |

| Pest and disease outbreaks | Yes/no | Present (reported qualitatively) |

| Tenure insecurity | Yes/no | Present (reported qualitatively) |

| Labor shortage | Yes/no | Present (reported qualitatively) |

| Security threats (theft, conflict) | Yes/no | 1.31% yes; 98.69% no |

| G. Adoption Conditions and Production Practices | ||

| Rice–fish seasons | Dry/wet | 78.6% dry; 69% wet |

| Access to rice seed | Yes/No | 83.84% yes; 15.72% no |

| Access to fish seed (baseline) | Yes/No | 51.97% yes; 47.16% no |

| Fish feed source | Purchased/Kitchen waste/Self-made/Other | 74.24% purchased; 20.98% kitchen waste; 6.55% self-made feed; 8.73% other |

| Market access improvement | % Yes | 67.25% improved |

| Fish price | Mean, median | NGN 1046.28 mean; NGN 1000 median |

| Purpose of adopting rice–fish | Sale + consumption/Sale only/Consumption only | 73.6% both; 19.65% sale; 6.99% consumption |

| Production cycles per year | One/Two/Three | 40.61% one; 53.71% two; 5.68% three |

| Outcomes | Key Predictors (Significance) |

|---|---|

| More income | None |

| Food access | Farm size (p < 0.001); pesticide/herbicide use (p = 0.017, negative) |

| Healthcare | Access to more land (p < 0.001); labor affordability (p < 0.001); farm size (p = 0.032); pesticide/herbicide use (p = 0.037, negative) |

| Education support | Access to more land (p < 0.001); labor affordability (p = 0.004); farm size (p = 0.049) |

| Dietary diversity | Access to more land (p < 0.001) |

| More access to agricultural input | Access to more land (p = 0.034); labor affordability (p < 0.001); farm size (p = 0.017) |

| Financial stability (less worry about money) | Farm size (p = 0.031); household size (p = 0.002, negative) |

| Enhanced social status | Access to more land (p = 0.011); labor affordability (p < 0.001); farm size (p = 0.015); pesticide/herbicide use (p < 0.001, negative) |

| Outcomes | % Improved | % No Change | % Declined |

|---|---|---|---|

| More income | 96.1 | 3.1 | 0.8 |

| Food security (access) | 56.3 | 43.7 | 0.0 |

| Dietary diversity | 30.6 | 69.4 | 0.0 |

| Healthcare spending capacity | 35.1 | 61.9 | 3.0 |

| Education support (school fees) | 28.4 | 66.3 | 5.3 |

| Enhanced social status | 27.9 | 69.0 | 3.1 |

| More access to agricultural input | 24.9 | 75.1 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ajayi, O.; Myo, A.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J. Rice–Fish Integration as a Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods Among Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from DPSIR-Informed Analysis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2026, 18, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010498

Ajayi O, Myo A, Cheng Y, Li J. Rice–Fish Integration as a Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods Among Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from DPSIR-Informed Analysis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010498

Chicago/Turabian StyleAjayi, Oluwafemi, Arkar Myo, Yongxu Cheng, and Jiayao Li. 2026. "Rice–Fish Integration as a Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods Among Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from DPSIR-Informed Analysis in Sub-Saharan Africa" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010498

APA StyleAjayi, O., Myo, A., Cheng, Y., & Li, J. (2026). Rice–Fish Integration as a Pathway to Sustainable Livelihoods Among Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from DPSIR-Informed Analysis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 18(1), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010498