Sediment Distribution, Depositional Trends, and Their Impact on the Operational Longevity of the Jiahezi Reservoir

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

2.1. River and Reservoir Characteristics

2.2. Hydrological Characteristics

3. Sampling Strategy and Methodology

4. Hydrodynamic and Sediment Transport Model

4.1. Model Principles

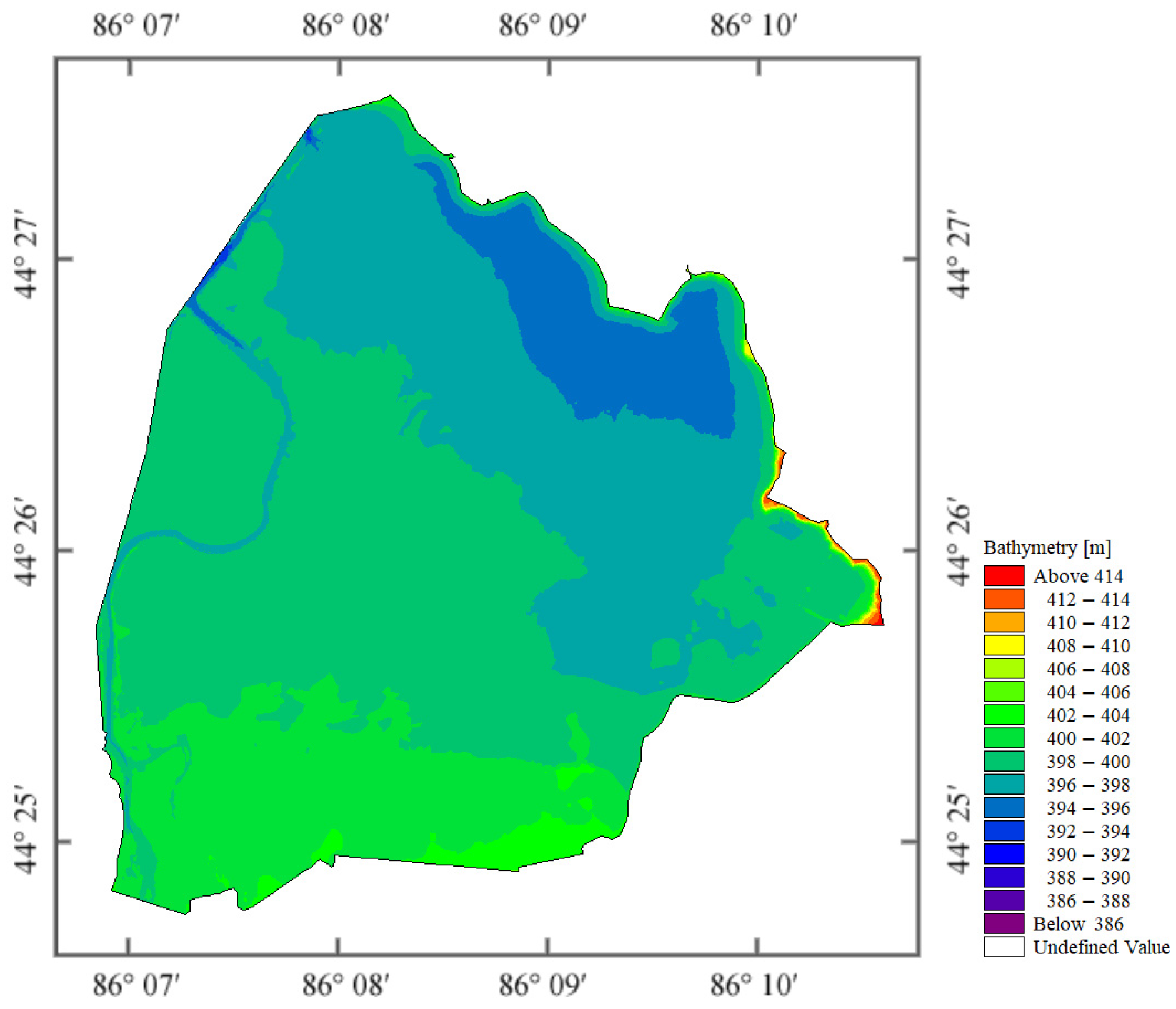

4.2. Model Construction

4.3. Boundary Conditions

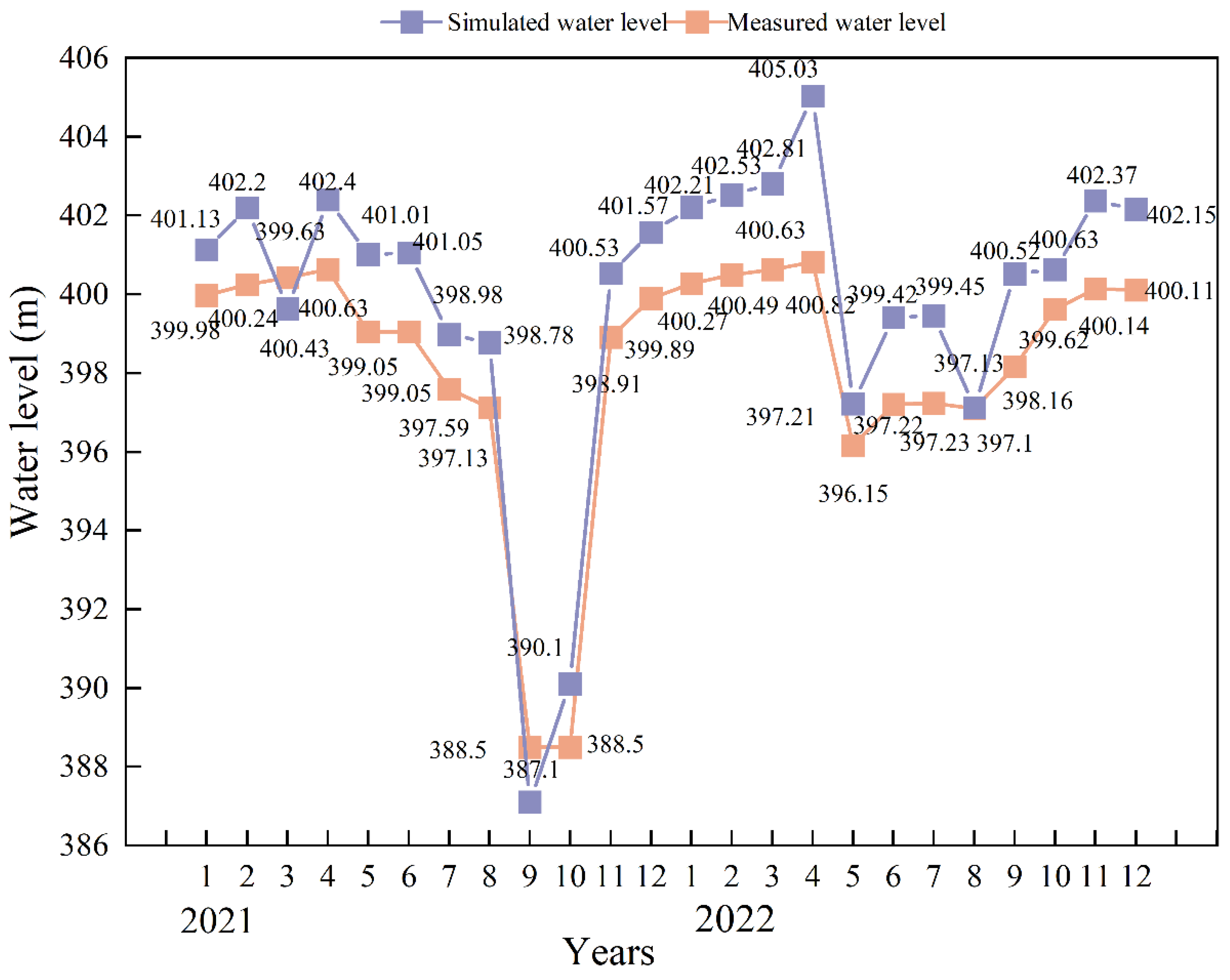

4.4. Model Validation

4.5. Data Coverage

5. Reservoir Simulation Operating Conditions

- (1)

- Wet Season (September–October 2023)—This period, which is marked by the transition from flood to normal flow conditions, is characterized by sharp inflow fluctuations and is considered highly representative of wet-season dynamics. The corresponding sediment concentration was 1.56 kg/m3, with an initial water level was 398.68 m. The sluice openings at the west and east outlets were 0.95 m and 0.27 m in September, and 0.14 m and 0 m in October, respectively.

- (2)

- Dry Season (February–March 2021)—This interval exhibits consistently low inflow rates, closely reflecting actual dry season reservoir operations. The measured sediment concentration was 0.035 kg/m3, with an initial water level of 400.02 m. The sluice openings at the west and east outlets were 0.17 m and 0 m in February, and 0.15 m and 0 m in March, respectively.

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Sampling Results and Analysis

6.1.1. Particle Size Distribution Along the Flow Direction and Depth Profile

6.1.2. Particle Size Distribution Throughout the Jiahezi Reservoir

6.2. Flow Velocity Field Variations

6.2.1. During the Wet Season

6.2.2. During the Dry Season

6.3. Scour and Deposition Characteristics in Reservoir Channels

6.4. Spatial Distribution of Sediment Size Fractions

6.4.1. During the Wet Season

6.4.2. During the Dry Season

6.5. Scouring and Silting Variations in the Reservoir Area

6.5.1. During the Wet Season

6.5.2. During the Dry Season

7. Discussion

7.1. Hydrodynamic Sorting of Sediments from River Channel to Reservoir Analysis

7.2. Mechanisms of Hydrodynamic Change in the Reservoir Area

- Primary Factors Leading to Increased Flow Velocity

- 2.

- Primary Factors Leading to Decreased Flow Velocity

7.3. Erosion-Deposition Zones in the Reservoir

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| η | the water level (m) |

| d | the static water depth (m) |

| h | the total water depth (m) |

| u | the depth-averaged velocity components in the x directions (m/s) |

| v | the depth-averaged velocity components in the y directions (m/s) |

| f | the Coriolis force coefficient (-) |

| ω | the Earth’s angular velocity (rad/s) |

| φ | the local latitude (rad) |

| g | the gravitational acceleration (m/s2) |

| ρ | the density of water (kg/m3) |

| ρ0 | the density of water (kg/m3) |

| Pa | the local atmospheric pressure (Pa) |

| Sxx | radiation stress components (Pa) |

| Sxy | radiation stress components (Pa) |

| Syx | radiation stress components (Pa) |

| τsx | wind shear stresses on the water surface (Pa) |

| τsy | wind shear stresses on the water surface (Pa) |

| τbx | bed shear stresses (Pa) |

| τby | bed shear stresses (Pa) |

| Txx | horizontal viscous stress components (Pa) |

| Txy | horizontal viscous stress components (Pa) |

| Tyy | horizontal viscous stress components (Pa) |

| S | a general source term (kg/(m3 s)) |

| us | the x components of velocity due to point or distributed sources (m/s) |

| vs | the y components of velocity due to point or distributed sources (m/s) |

| c | the depth-averaged sediment concentration (kg/m3) |

| h | the water depth (m) |

| QL | the horizontal source term flow rate per unit area (m/s) |

| CL | the source sediment concentration (kg/m3) |

| u | the depth- averaged flow velocities in the x directions (m/s) |

| v | the depth- averaged flow velocities in the y directions (m/s) |

| Dx | the turbulent diffusion coefficients in the x directions (m2/s) |

| Dy | the turbulent diffusion coefficients in the y directions (m2/s) |

| S | s the bed exchange (erosion/deposition) source term (kg/(m3·s). |

| Fe | the deposition rate (kg/(m2·s)) |

| Fd | the erosion rate (kg/(m2·s)) |

| ω | the settling velocity of sediments (m/s) |

| cb | the concentration of suspended sediment near the bed surface (kg/m3) |

| Dsg | the geometric mean particle size of suspended sediment (m) |

| d | the diameter of sediment (m) |

| c | represents the sediment concentration in water (kg/m3) |

| Es | the sediment entrainment coefficient (-) |

| p | the Volume fraction of bottom sediments (-) |

| Rj | the sand grain Reynolds number (-) |

| , | representative Coefficient (-) |

| u∗ | the shear velocity of the bed layer (m/s) |

| μf | the Manning coefficient (s/m1/3) |

| rw | the upper interface to bed resistance ratio (-) |

References

- Tsyplenkov, A.; Grachev, A.; Yermolaev, O.; Golosov, V. Impacts of post-Soviet land-use transformation on sediment dynamics in the Western Caucasus. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 132965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, L.T. Measuring the impact of streamflow drought and reservoir sediment on the technical and scale inefficiencies of hydroelectric power plants. Energy 2025, 322, 135612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daus, M.; Koberger, K.; Koca, K.; Beckers, F.; Fernández, J.E.; Weisbrod, B.; Dietrich, D.; Gerbersdorf, S.U.; Glaser, R.; Haun, S.; et al. Interdisciplinary Reservoir Management-A Tool for Sustainable Water Resources Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Xie, J.K.; Xu, Y.P.; Guo, Y.X.; Wang, Y.J. Scenario-based multi-objective optimization of reservoirs in silt-laden rivers: A case study in the Lower Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Fu, L. Problems of reservoir sedimrntation in China. J. Lake Sci. 1997, 82, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gong, Z.; Li, J.; Mu, L.; Wang, Q. Study on Changes in Water and Sediment Regime and Siltation Reduction Measures of Xiaoshixia Reservoir in Xinjiang. Yellow River 2024, 46, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, A.; Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Zhang, G. Analysis of reservoir siltation in China. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 53, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Deng, A.; Hu, H. Analysis of factors affecting the annual average deposition rate of reservoirs. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, F. A Review of Reservoir Sedimentation Control and Storage Capacity Recovery. Yellow River 2019, 41, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Ludeña, S.; Toapaxi, J.A.; Castillo, L.G. Efficacy of Sediment Flushing for varying Bed Slopes and Sediment Grain Sizes. In Proceedings of the 39th IAHR World Congress on from Snow to Sea, Ctr Studies & Experimentat Publ Works, Spain Water, Granada, Spain, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1208–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrees, A.; Taha, A.T.B.; Mohamed, A.M. Prediction of sustainable management of sediment in rivers and reservoirs. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, F.; Xing, Z.; Xu, L.; Qi, J. Study on Sediment Grain Size in the Flood Season of the Songnen River and Trend Analysis of Main Stream Particle Size. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2019, 50, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tang, H.; Tang, L.; Chen, H. Analysis of Flow and Sediment Characteristics in the Yongjiang River and Its Estuarine Sea Area. In Proceedings of the 10th National Symposium on Basic Theories of Sediment Research, Wuhan, China, 8–11 November 2017; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, S.; Li, T.; Guo, Y.; Wang, P. Analysis of Riverbed Sediment Composition in Xiliugou River. Yellow River 2018, 40, 7–10+14. [Google Scholar]

- Minocha, S.; Hossain, F. GRILSS: Opening the gateway to global reservoir sedimentation data curation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1743–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, C.M.; Hanasaki, N.; Komori, D.; Tanaka, K.; Kiguchi, M.; Champathong, A.; Sukhapunnaphan, T.; Yamazaki, D.; Oki, T. Assessing the impacts of reservoir operation to floodplain inundation by combining hydrological, reservoir management, and hydrodynamic models. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 7245–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pszonka, J.; Schulz, B.; Sala, D. Application of mineral liberation analysis (MLA) for investigations of grain size distribution in submarine density flow deposits. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 129, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, S.; Sotiri, K.; Fuchs, S. Review of methods of sediment detection in reservoirs. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2024, 39, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghzayel, A.; Beaudoin, A. Three-dimensional numerical study of a local scour downstream of a submerged sluice gate using two hydro-morphodynamic models, SedFoam and FLOW-3D. Comptes Rendus Mec. 2023, 351, 525–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Al-Hamdan, M.; Wren, D. Development of a Two-Dimensional Hybrid Sediment-Transport Model. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.L.; Harada, D.; Egashira, S. Modeling of Sediment Transport Process in Drainage Basins. In Proceedings of the 39th IAHR World Congress on from Snow to Sea, Ctr Studies & Experimentat Publ Works, Spain Water, Granada, Spain, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 718–727. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Z.K.W.; Dai, Q. Comparison and Application of Mathematical and Physical Model Results for Reservoir Sediment. J. Sediment Res. 1994, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvidchenko, A.B.; Pender, G. Flume study of the effect of relative depth on the incipient motion of coarse uniform sediments. Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Three-Dimensional Simulation on Diversion and Sand Dischargecharacteristics of a Typical Bend Channel Head Under Multi-Sedimentenvironment. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Xinjiang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Deng, J.; Chen, L. Characteristics and Trends of Sedimentation in the Three Gorges Reservoir under Complex Boundary Conditions. Adv. Water Sci. 2023, 34, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, D. Numerical Simulation Analysis of Sediment Erosion and Deposition in River-type Reservoirs. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2013, 44, 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, E.; Shao, X.; Zhang, X. Numerical Simulation of the Sedimentation Morphology in the Xiaolangdi Reservoir. Adv. Water Sci. 2020, 31, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Jin, Z.; Liang, D.; Nones, M.; Zhou, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of flood control storage sedimentation in the Three Gorges Reservoir, Changjiang River, China. Catena 2024, 243, 108214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfan, J.; Ginting, B.; Rimawan, R. Assessment of reservoir sedimentation and mitigation measures using 2D hydrodynamic modeling: Case study of Pandanduri Reservoir, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Bandung, Indonesia, 14–15 November 2023; p. 012018. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z. Two—Dimensional mathematical model of sediment deposition in hydropower station reservoirs. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2020, 38, 910–914. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.J.; Qi, F. The effects of sampling design on spatial structure analysis of contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 224, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50487-2008; Code for Engineering Geological Investigation of Water Resources and Hydropower. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Bi, C.F.; Ran, D.C.; Shen, M.; Wang, L. Analysis of the Particle Size Distribution of Sediment Depleted by Warping Dams in the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River. Yellow River 2011, 33, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- SL 42-2010; Technical Standard for Determination of Sediment Particle Size in Open Channels. Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Bradford, S.F.; Katopodes, N.D. Hydrodynamics of turbid underflows. I: Formulation and numerical analysis. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1999, 125, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Parker, G. Experiments on the entrainment of sediment into suspension by a dense bottom current. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1993, 98, 4793–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, C.; Celi, D.; Concha, F. Determination of the volumetric solids fraction of saturated polydisperse ore tailing sediments. Powder Technol. 2017, 305, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Fukushima, Y.; Pantin, H.M. Self-accelerating turbidity currents. J. Fluid Mech. 1986, 171, 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Cao, Z.X. Fully coupled mathematical modeling of turbidity currents over erodible bed. Adv. Water Resour. 2009, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Pender, G.; Wallis, S.; Carling, P. Computational dam-break hydraulics over erodible sediment bed. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2004, 130, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, G.; Poesen, J. Estimating trap efficiency of small reservoirs and ponds: Methods and implications for the assessment of sediment yield. Prog. Phys. Geogr.-Earth Environ. 2000, 24, 219–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50145-2007; Standard for Engineering Classification of Soil. Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Lintern, A.; Leahy, P.J.; Zawadzki, A.; Gadd, P.; Heijnis, H.; Jacobsen, G.; Connor, S.; Deletic, A.; McCarthy, D.T. Sediment cores as archives of historical changes in floodplain lake hydrology. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.G.; McCallum, A.; Kent, D.; Rathnayaka, C.; Fairweather, H. A review of sedimentation rates in freshwater reservoirs: Recent changes and causative factors. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 85, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, C.A.; Leckie, D.A.; Smith, M.G. Point bar sedimentation and erosion produced by an extreme flood in a Check for sand and gravel-bed meandering river. Sediment. Geol. 2018, 377, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, A.M.; Otero, L.; Ospino, S.; Cueto, J. Interactions between Hydrodynamic Forcing, Suspended Sediment Transport, and Morphology in a Microtidal Intermediate-Dissipative Beach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhakar, M.; Mohan, S.; Ghoshal, K.; Kumar, J.; Singh, V.P. Semianalytical Solution for Nonequilibrium Suspended Sediment Transport in Open Channels with Concentration-Dependent Settling Velocity. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2022, 27, 04021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Hu, P.; Li, W.; Li, J. Sediment Transport Mechanics, 1st ed.; China Water Resources and Hydropower Press: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, R.L.; Schramkowski, G.P.; Dijkstra, Y.M.; Schuttelaars, H.M. Time Evolution of Estuarine Turbidity Maxima in Well-Mixed, Tidally Dominated Estuaries: The Role of Availability- and Erosion-Limited Conditions. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2018, 48, 1629–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Ghoshal, K. Hydrodynamic interaction in suspended sediment distribution of open channel turbulent flow. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 49, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Jiang, L.G.; Ma, D.H.; Liu, J.G. SWOT Unveils the Hidden Hydrodynamics of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL118488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedashraf, O.; Akhtari, A.A. Experimental and numerical investigation of water flow behaviour in sharply curved 60° open-channel bends. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2025, 50, e6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.; Vitale, A.J.; Parker, G.; García, M.H. Hydraulic resistance in mixed bedrock-alluvial meandering channels. J. Hydraul. Res. 2021, 59, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Fluid Mechanics, 1st ed.; China Water Resources and Hydropower Press: Beijing, China, 2024; p. 281. [Google Scholar]

- Kaffas, K.; Pisaturo, G.R.; Premstaller, G.; Hrissanthou, V.; Penna, D.; Righetti, M. Event-based soil erosion and sediment yield modelling for calculating long-term reservoir sedimentation in the Alps. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlácek, J.; Bábek, O.; Grygar, T.M.; Lendáková, Z.; Pacina, J.; Stojdl, J.; Hosek, M.; Elznicová, J. A closer look at sedimentation processes in two dam reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.A.; Xu, X.Z.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Dang, W.Q.; Liu, B. The use of check dams in watershed management projects: Examples from around the world. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.L. Classification of Management Alternatives to Combat Reservoir Sedimentation. Water 2020, 12, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Critical Parameter Adjustments for Hydrodynamic Simulations | |

|---|---|

| Dry–Wet Boundary | Water Depth (m) |

| Drying Depth | 0.005 |

| Flooding Depth | 0.05 |

| Wetting Depth | 0.1 Coefficients |

| Eddy Viscosity Coefficient | 0.28 |

| Manning Coefficient | 32 (m−3/s) |

| Critical Parameter Adjustments for the Sediment Module | |

|---|---|

| Sediment Particle Density | 2650 (kg/m3) |

| Sediment Critical Shear Stress | 0.07 (N/m2) |

| Sediment Classes | 5 |

| Number of Layers | 2 |

| No. | Sampling Point Elevation (m) | Siltation Thickness (m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Data (2021) | Measured Value (2022) | Simulated Value (2022) | Simulated Value (2022) | Measured Value (2022) | |

| 1 | 398.30 | 395.582 | 395.48 | −2.82 | −2.718 |

| 2 | 398.63 | 395.372 | 396.406 | −2.224 | −3.258 |

| 3 | 398.18 | 403.325 | 402.19 | 4.01 | 5.145 |

| 4 | 397.30 | 398.200 | 397.70 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| 5 | 396.66 | 396.205 | 395.13 | −1.53 | −0.455 |

| 6 | 396.36 | 396.980 | 397.05 | 0.69 | 0.62 |

| 7 | 395.82 | 396.757 | 396.93 | 1.11 | 0.937 |

| 8 | 395.43 | 394.73 | 395.01 | −0.42 | −0.7 |

| 9 | 396.71 | 397.85 | 397.05 | 0.34 | 1.14 |

| 10 | 394.88 | 396.44 | 397.03 | 2.15 | 1.56 |

| Sampling Points | Coarse Sand (%) (0.5 < d ≤ 2 mm) | Med. Sand (%) (0.25 < d ≤ 0.5 mm) | Fine Sand (%) (0.075 < d ≤ 0.25 mm) | Silt (%) (0.005 < d ≤ 0.075 mm) | Clay (%) (d ≤ 0.005 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | 1.6 | 6.9 | 19.3 | 57.9 | 14.2 |

| (M) | 1.6 | 8.7 | 28.1 | 48.3 | 13.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Jiang, B.; Wan, C.; Zong, Q.; Ren, H. Sediment Distribution, Depositional Trends, and Their Impact on the Operational Longevity of the Jiahezi Reservoir. Sustainability 2026, 18, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010500

Li J, Liu Z, Wu W, Jiang B, Wan C, Zong Q, Ren H. Sediment Distribution, Depositional Trends, and Their Impact on the Operational Longevity of the Jiahezi Reservoir. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010500

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jun, Zhenji Liu, Weidong Wu, Bo Jiang, Chen Wan, Quanli Zong, and Huili Ren. 2026. "Sediment Distribution, Depositional Trends, and Their Impact on the Operational Longevity of the Jiahezi Reservoir" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010500

APA StyleLi, J., Liu, Z., Wu, W., Jiang, B., Wan, C., Zong, Q., & Ren, H. (2026). Sediment Distribution, Depositional Trends, and Their Impact on the Operational Longevity of the Jiahezi Reservoir. Sustainability, 18(1), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010500