Mangrove-Derived Microbial Consortia for Sugar Filter Mud Composting and Biofertilizer Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Pretreatment

2.2. Composting Experiment Design

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and Purification

2.3.2. Metagenomic Sequencing

2.3.3. Auxiliary Microbiological Analysis

2.4. Measurement of Composting Parameters

2.5. High-Throughput Sequencing of Compost Samples

2.6. Pot Experiment Design

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Mangrove-Derived Microbial Strains

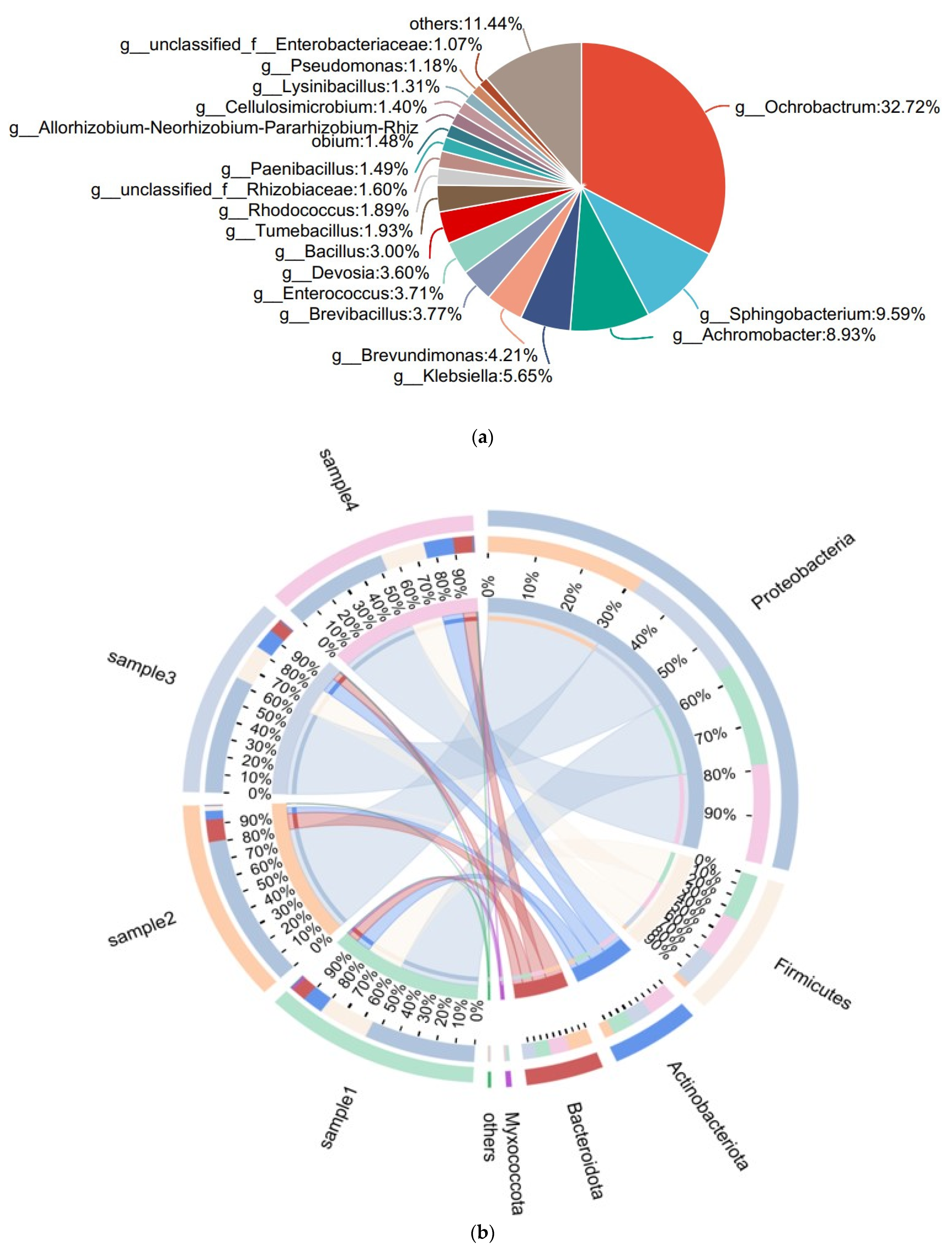

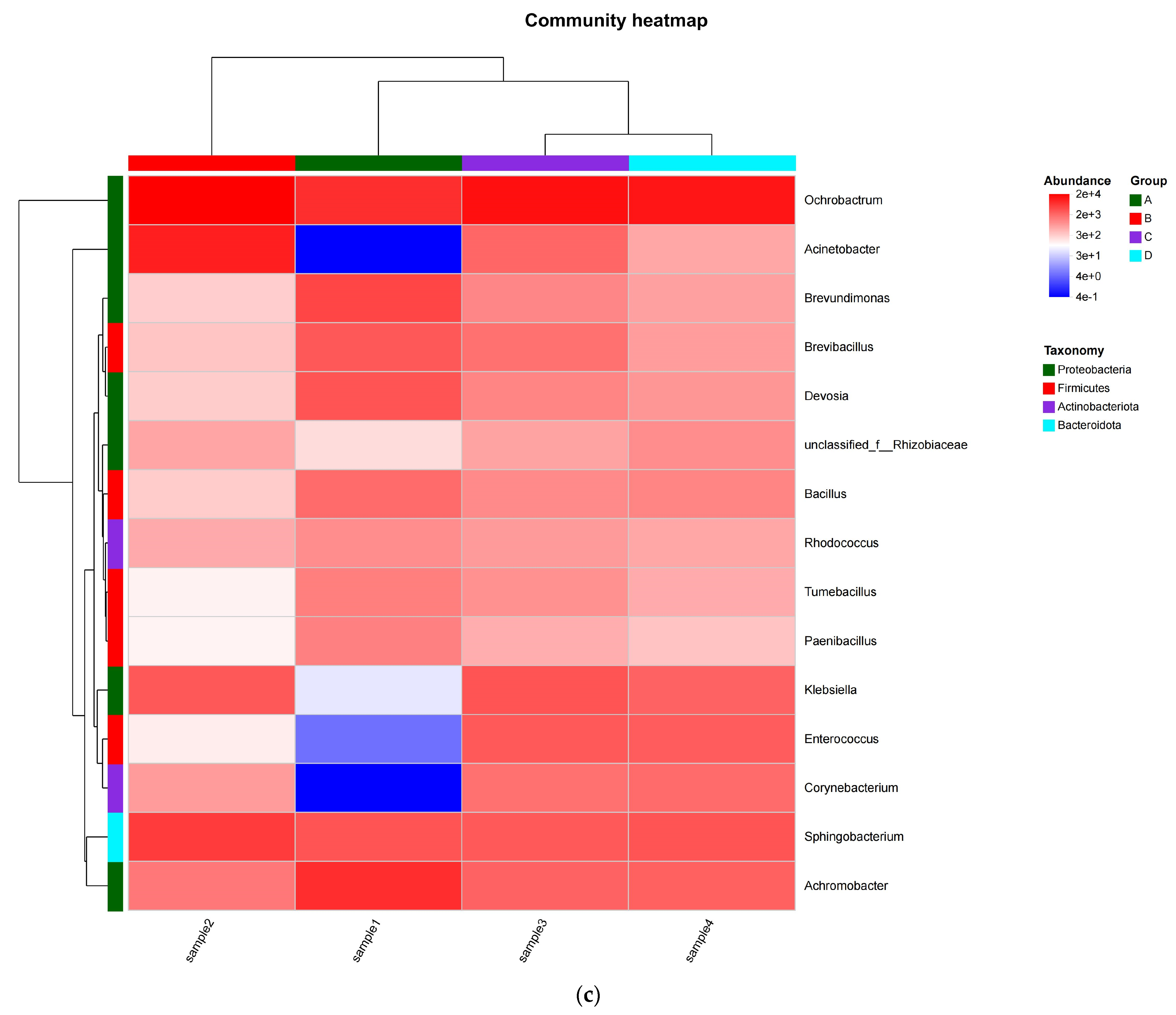

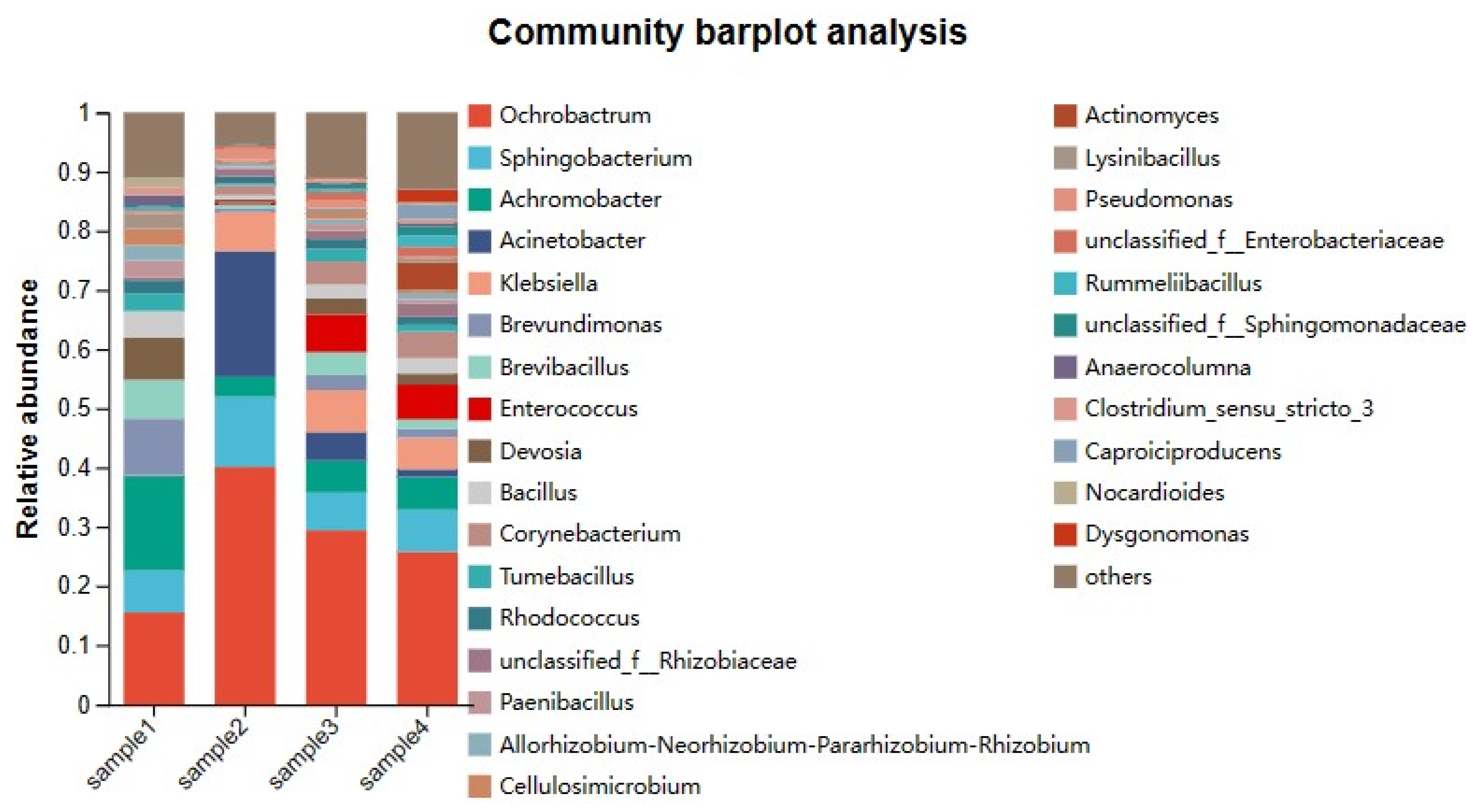

3.1.1. Microbial Community Diversity and Abundance

3.1.2. Multidimensional Profiling of Mangrove Bacterial Assemblages: Diversity, Distribution and Dynamics

3.1.3. Isolation of Nitrogen-Fixing Strain P1N2

3.2. Regulation of the Composting Process and Fertilization Efficiency by Mangrove-Derived Microbial Inoculants

3.2.1. Environmental Parameters of the Composting Process

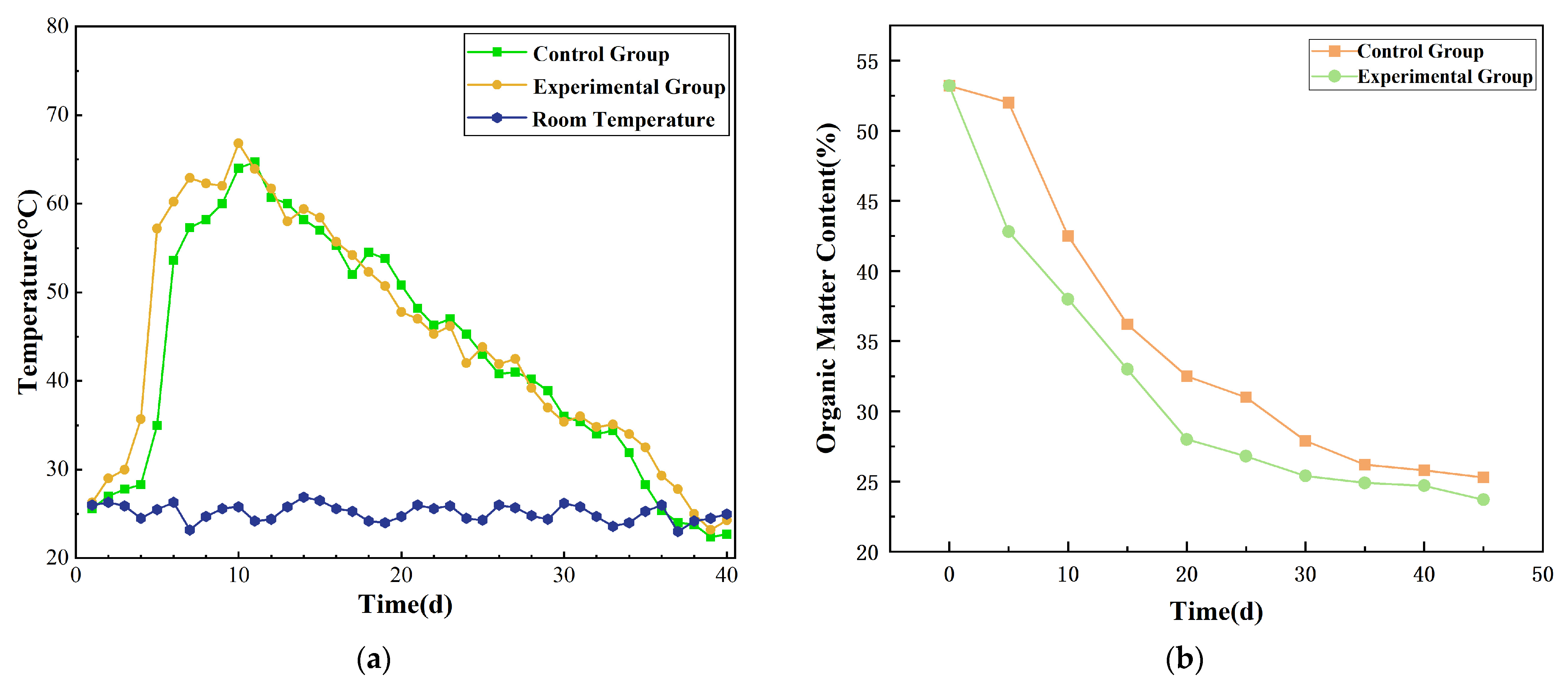

Temperature Dynamics

Changes in Organic Matter Content

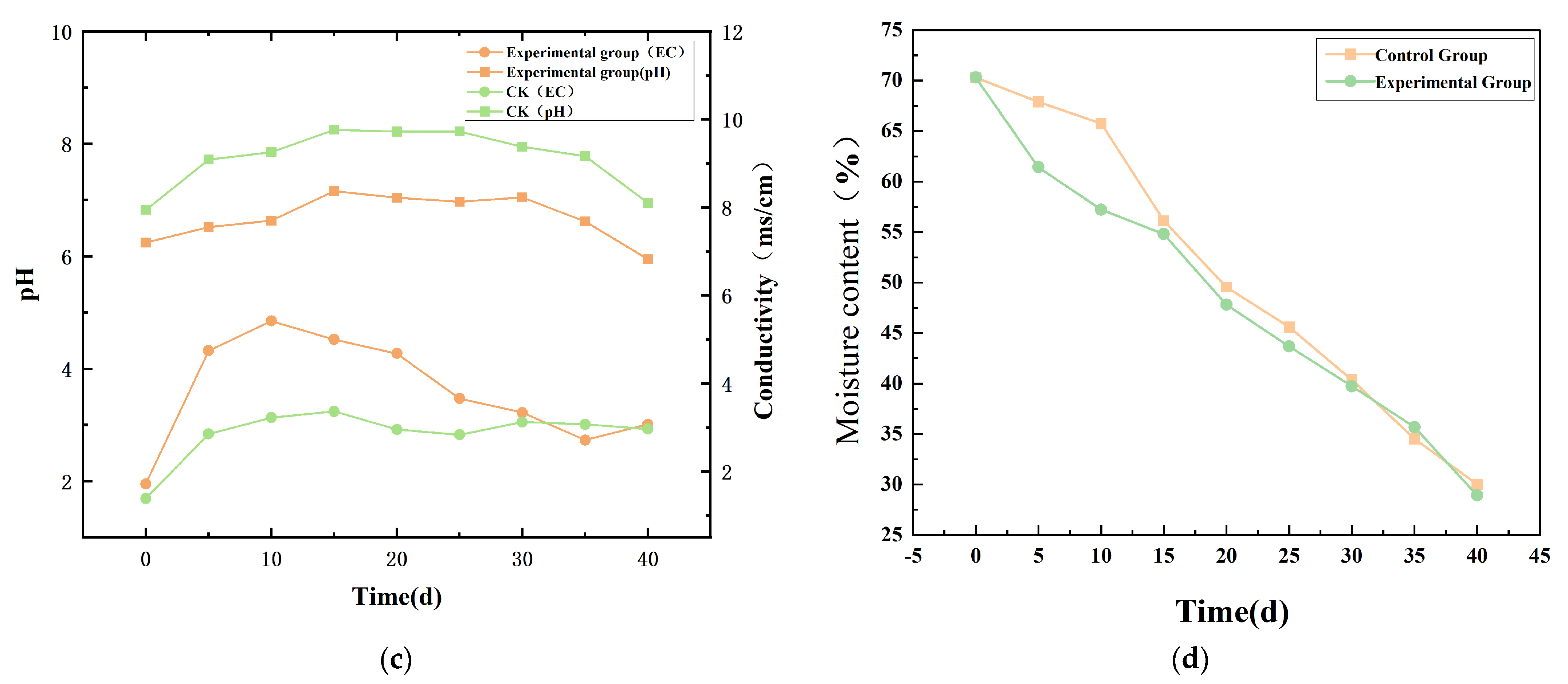

Electrical Conductivity (EC) and pH Dynamics

Moisture Content Variation

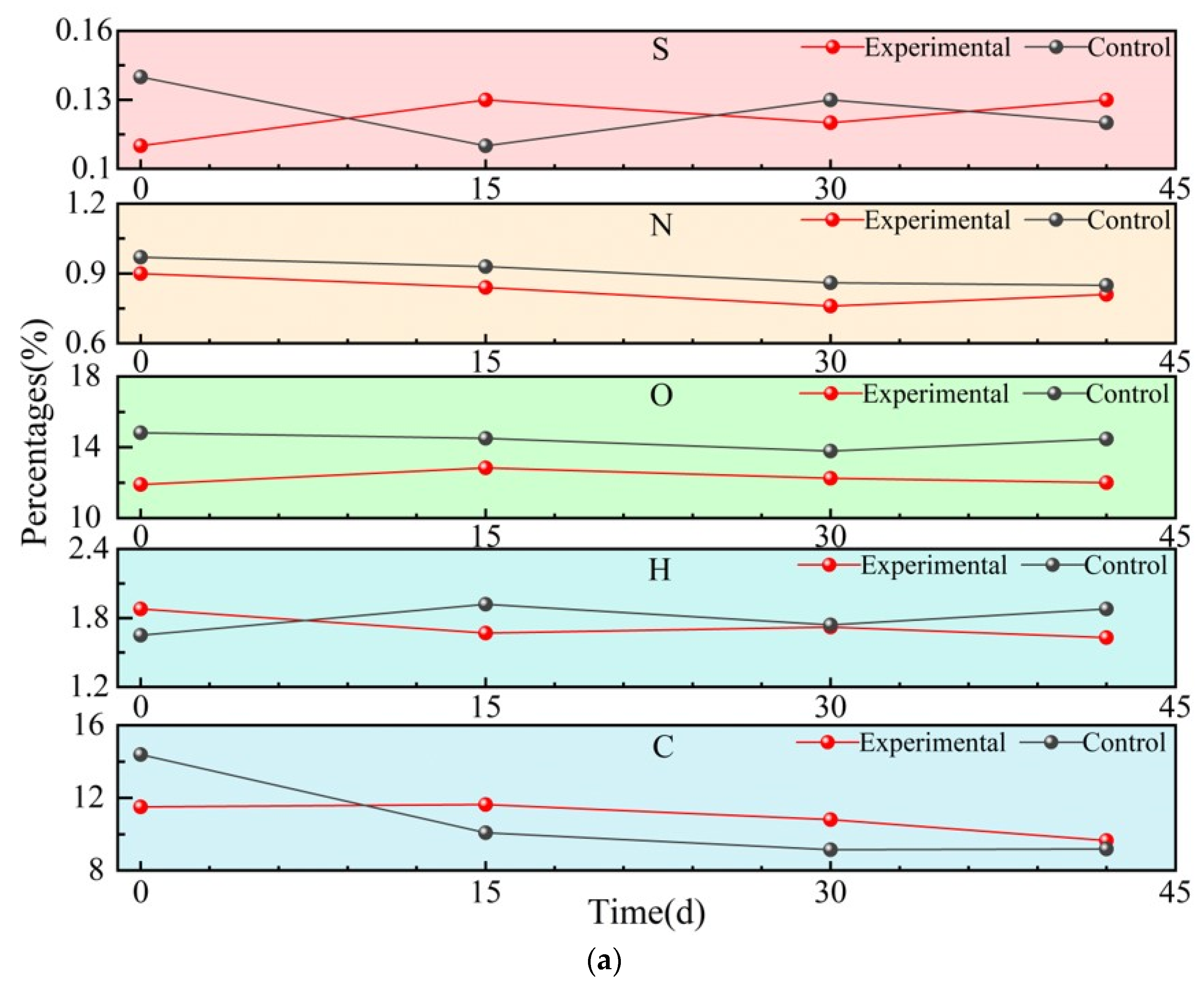

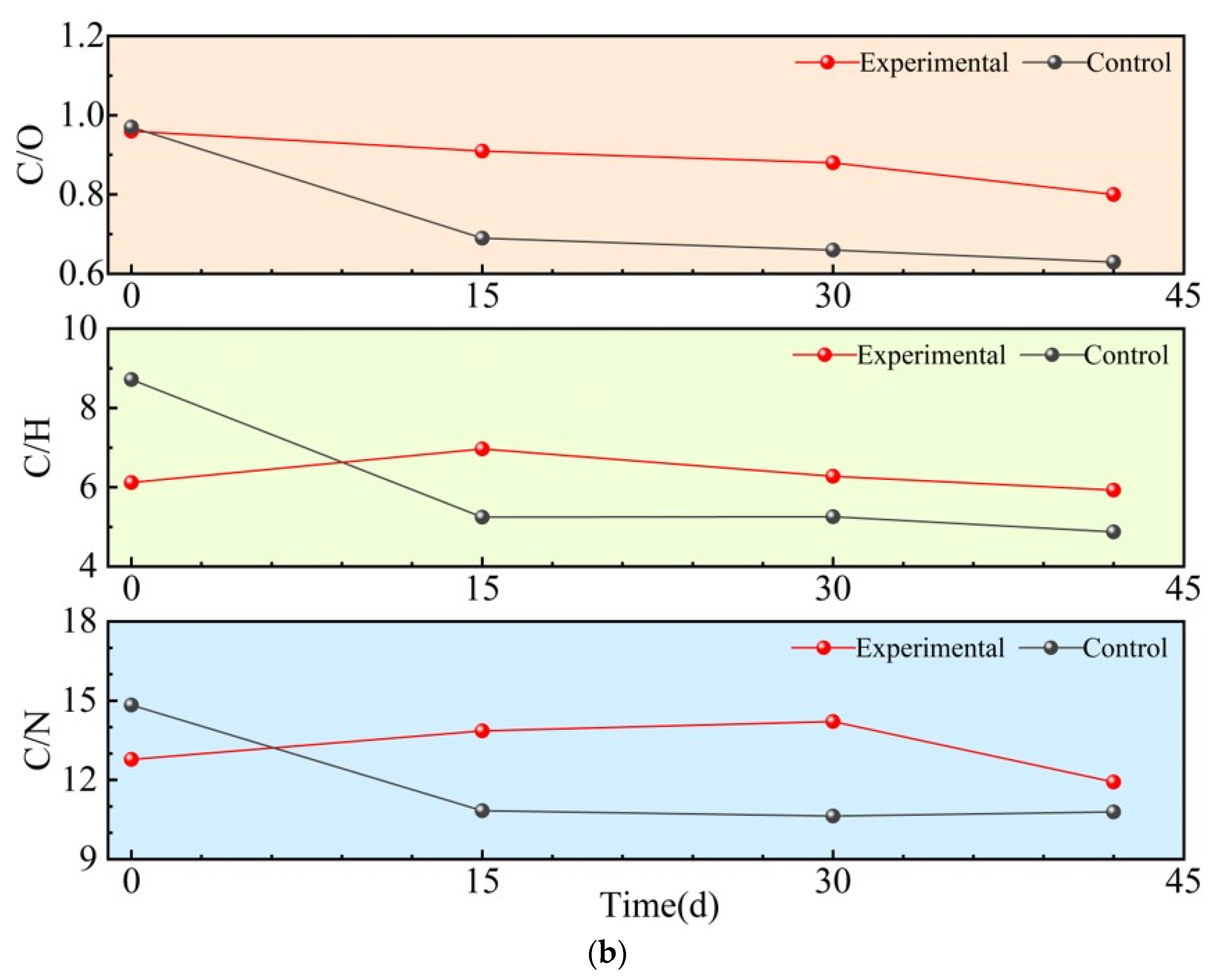

3.2.2. Elemental Composition

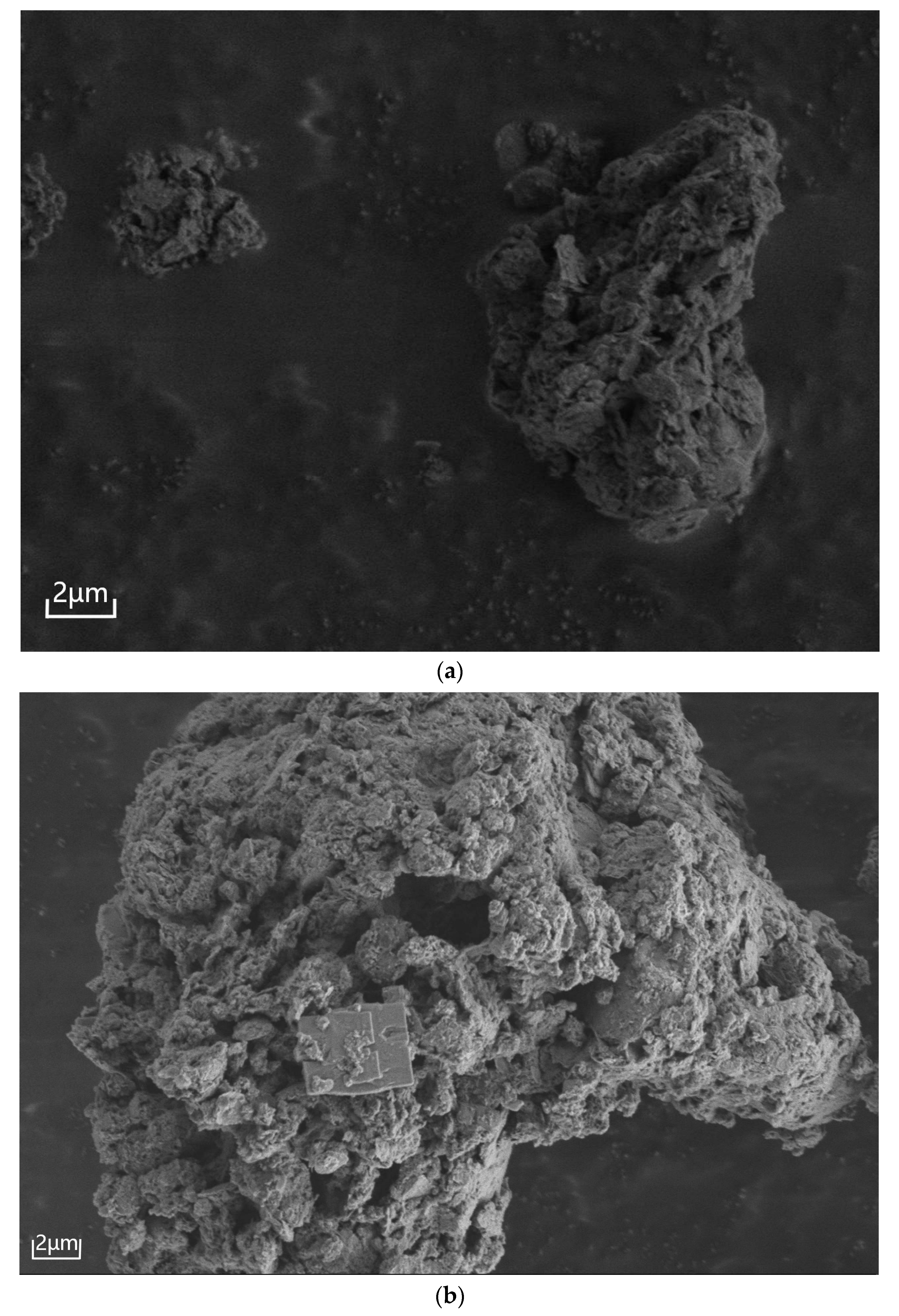

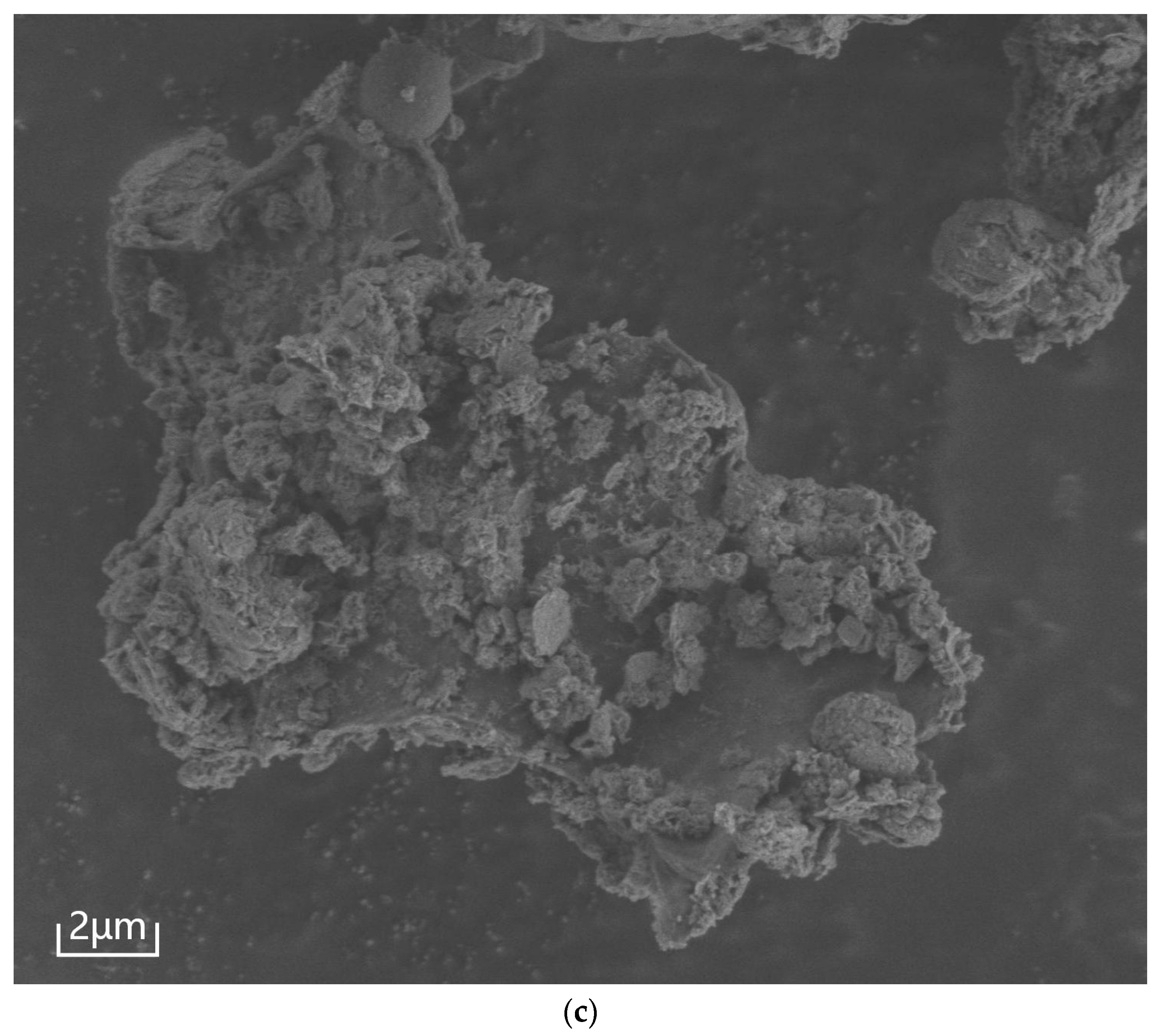

3.2.3. Microstructural Evolution of Humus

3.2.4. Bacterial Community Succession During Composting

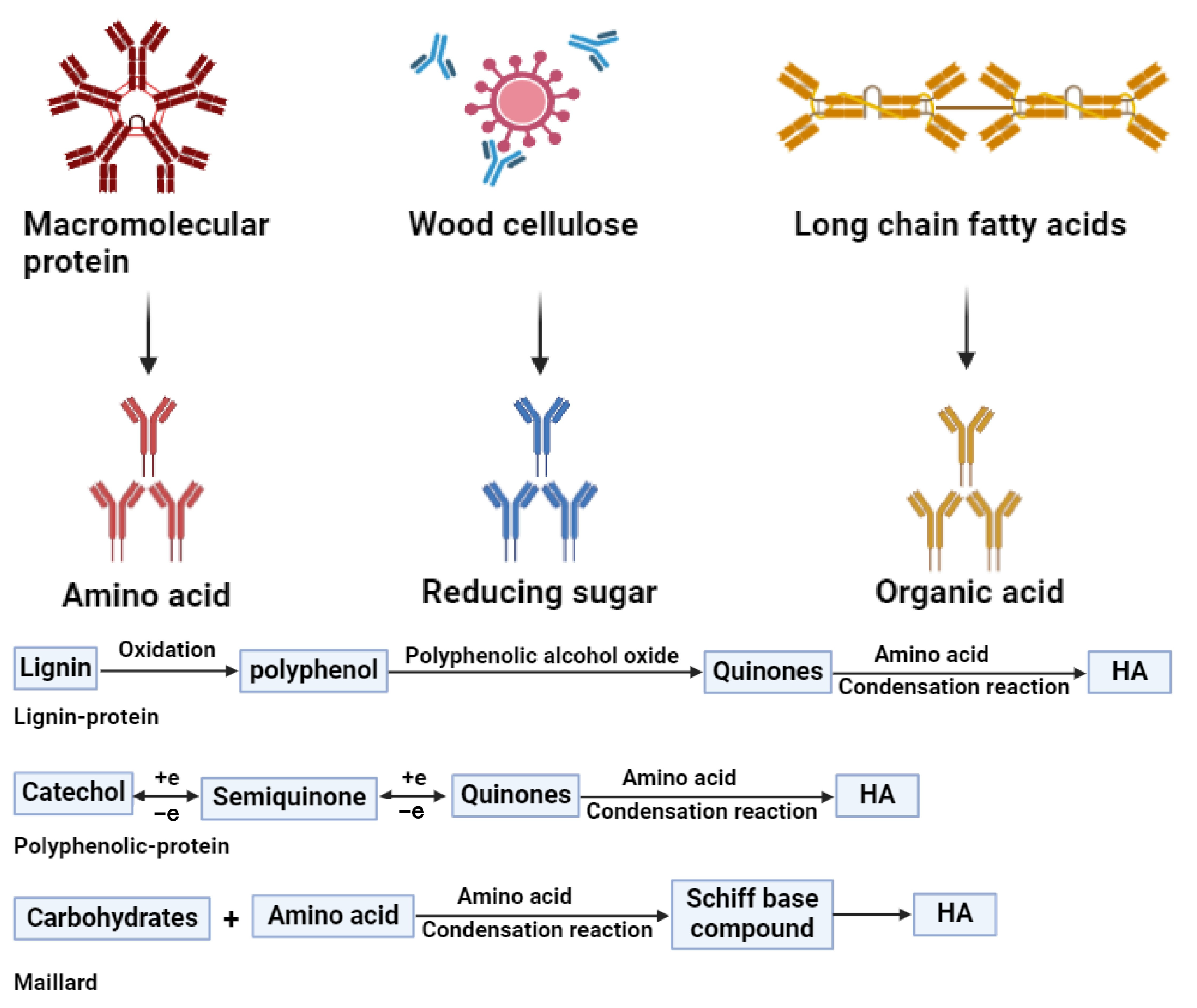

3.2.5. Mechanistic Insight into Composting Enhancement

- (1)

- the lignin–protein pathway, in which lignin oxidation products (polyphenols) react with nitrogenous compounds;

- (2)

- the polyphenol–protein pathway, where oxidized phenols (quinones) condense with amino acids;

- (3)

- the Maillard reaction, a non-enzymatic condensation between reducing sugars and amino compounds.

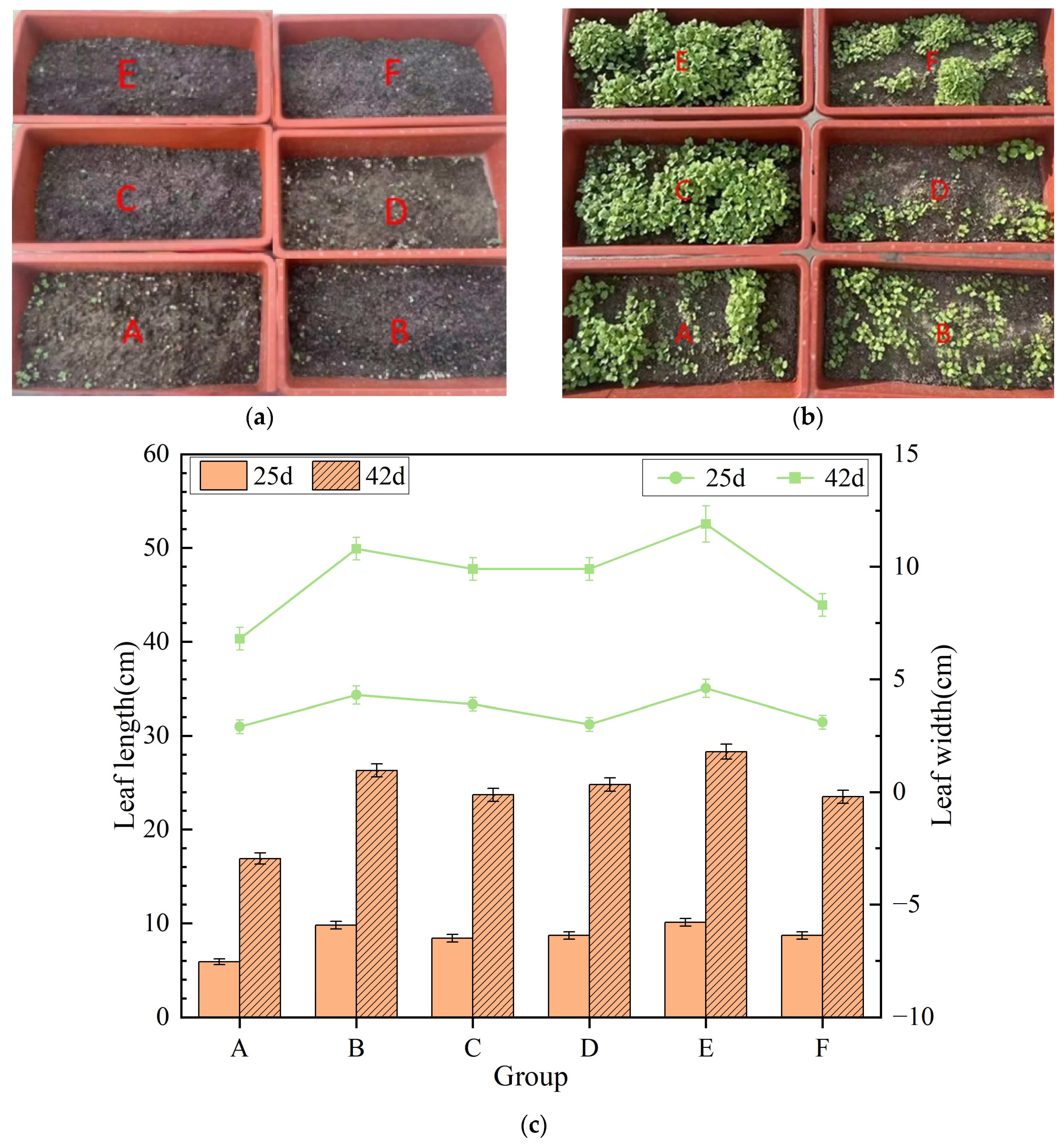

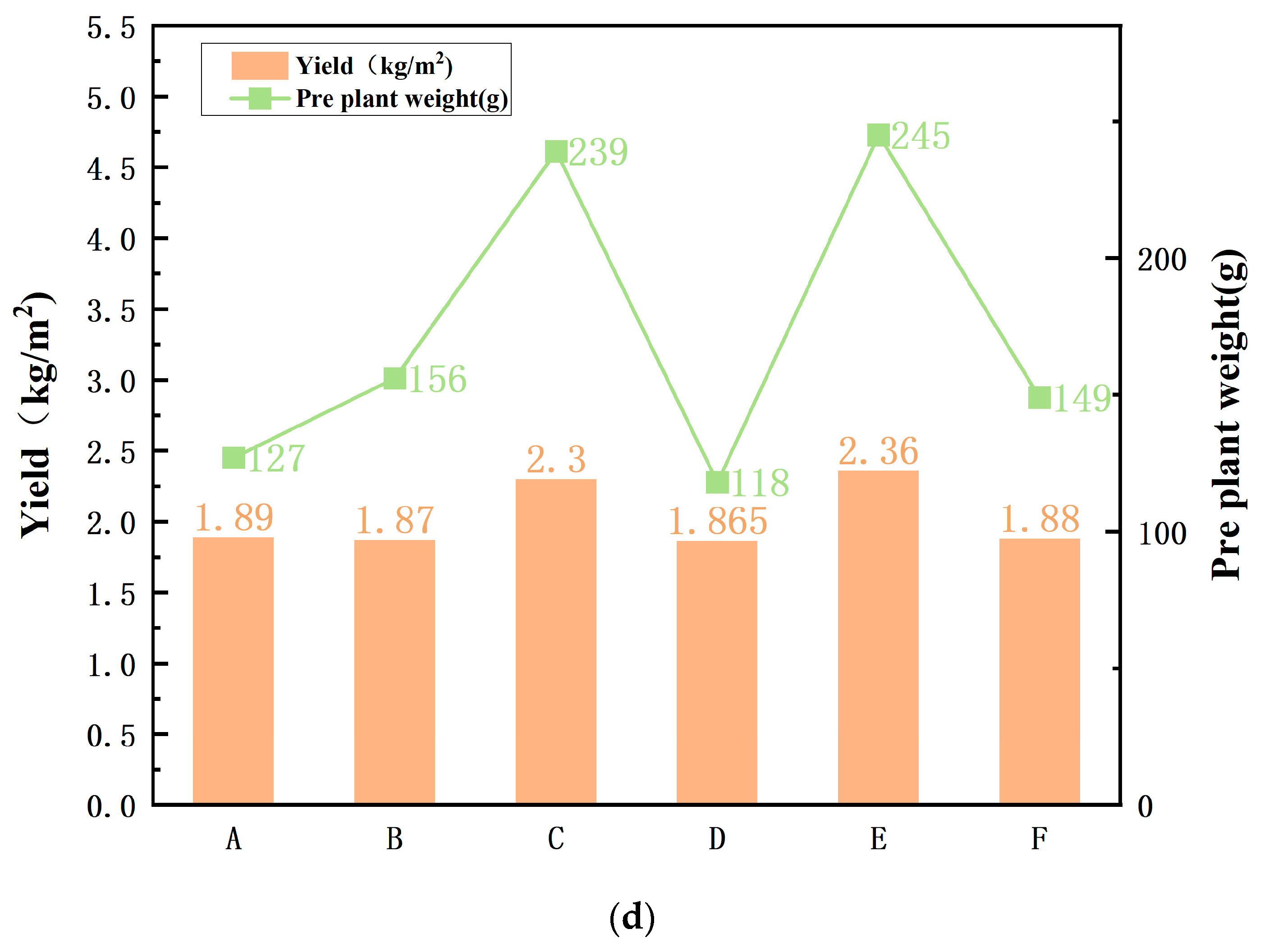

3.3. Pot Experiment and Evaluation of Fertilization Efficiency

- A—Soil amended with raw filter mud (no additional fertilizer);

- B—Soil treated with conventional organic fertilizer;

- C—Soil amended with compost produced using the mangrove microbial inoculant;

- D—Unfertilized control soil;

- E—Filter-mud-amended soil supplemented with the bio-inoculated compost;

- F—Soil treated with inorganic fertilizer.

3.3.1. Seedling Growth and Early Development

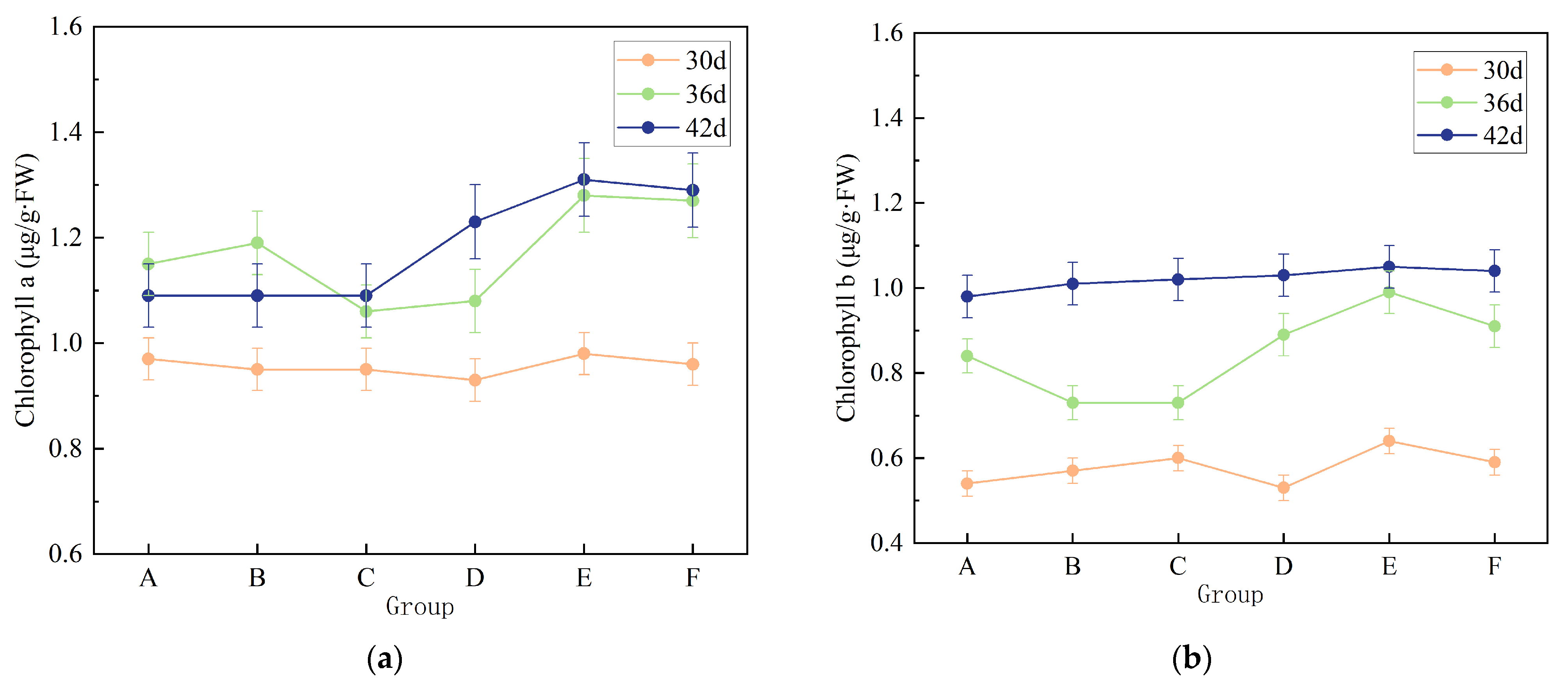

3.3.2. Effects of Different Treatments on Chlorophyll Content in Chinese Broccoli Leaves

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, L.D. Green and low-carbon development of Guangxi sugarcane sugar industry: Current status, challenges and strategies. Sugarcane Canesugar 2024, 53, 74–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Haynes, R.; Naidu, R. Use of Inorganic and Organic Wastes for in Situ Immobilisation of Pb and Zn in a Contaminated Alkaline Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.L.; Xie, Q.R.; Xie, L.L. Treatment of Congo red wastewater by high temperature modified sugar filter mud. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2019, 6, 1340–1343. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Impact and strategies of agricultural organic waste resource utilization on environmental protection. J. Agric. Catastrophol. 2024, 14, 187–189. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.S.; Lima, I.M. Identification of Microbial Populations in Blends of Worm Castings or Sugarcane Filter Mud Compost with Biochar. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, G.; Minhas, P.; Biswas, A.; Meena, K.K.; Pradhan, A.; Gawhale, B.; Choudhary, R.; Kumar, S.; Fagodiya, R.K.; Reddy, K.S. Assessment of Gains in Productivity and Water-Energy-Carbon Nexus with Tillage, Trash Retention and Fertigation Practices in Drip Irrigated Sugarcane. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211, 115294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooksawat, T.; Ngaopok, K.; Siripornadulsil, S.; Amnuaypanich, S.; Attapong, M.; Siripornadulsil, W. Sustainable Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate Biopolymers and Cellulose Microfibers from Sugarcane Waste. Process Biochem. 2025, 150, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Su, T.; Qin, F.; Su, L.; Wei, C.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Application Effects of Organic Manure from Sugarcane Filter on Chinese Flowering Cabbage. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 31, 796–801. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H. Bio-Organic Fertilizer Made through Fermentation of Filter Mud from Sugar Refinery. J. South. Agric. 2017, 48, 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, M.; Inamullah; Jamal, A.; Mihoub, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Radicetti, E.; Ahmad, I.; Naeem, A.; Ullah, J.; Pampana, S. Composting Sugarcane Filter Mud with Different Sources Differently Benefits Sweet Maize. Agronomy 2023, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.M.; Wright, M. Microbial Stability of Worm Castings and Sugarcane Filter Mud Compost Blended with Biochar. Cogent Food Agric. 2018, 4, 1423719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, W.; Yuan, J.; Li, G.; Luo, Y. Effects of Woody Peat and Superphosphate on Compost Maturity and Gaseous Emissions during Pig Manure Composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, L.; Du, H. Virulence Factors in Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 642484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, H.; Xia, L.; Schwarz, S.; Jia, H.; Yao, X.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Shao, D. Various Mobile Genetic Elements Carrying optrA in Enterococcus Faecium and Enterococcus Faecalis Isolates from Swine within the Same Farm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielaite, M.; Bartell, J.A.; Nørskov-Lauritsen, N.; Pressler, T.; Nielsen, F.C.; Johansen, H.K.; Marvig, R.L. Transmission and Antibiotic Resistance of Achromobacter in Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e02911-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Feng, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Tian, R.; Fan, F.; Ning, D.; Bates, C.T.; Hale, L.; Yuan, M.M. Winter Warming in Alaska Accelerates Lignin Decomposition Contributed by Proteobacteria. Microbiome 2020, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.G.; Du, S.Y.; Jia, H.W.; Yang, X.; Pan, Y. Bacterial community composition in sediments at different depths of mangrove forests. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 2223–2229. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklinsky-Sobral, J.; Araújo, W.L.; Mendes, R.; Geraldi, I.O.; Pizzirani-Kleiner, A.A.; Azevedo, J.L. Isolation and Characterization of Soybean-associated Bacteria and Their Potential for Plant Growth Promotion. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhen, X.; Kang, J. Variations in Enzyme Concentrations during High-Temperature Composting of Livestock and Poultry Manure and Study on Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2022, 16, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Lai, J.; Then, Y.; Vithanawasam, C. Effect of External Heat Source on Temperature and Moisture Variation for Composting of Food Waste; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1195, p. 12058. [Google Scholar]

- Zilong, Z.; Yu, X. Changes in the Spectral Characteristics of Hydrophilic Fraction in Compost Organic Matter; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 2011, p. 12069. [Google Scholar]

- Şeker, C.; Negiş, H.; Koçkesen, R. Influence of Maturation Time on Organic Matter Loss and Quality of Maize Stubble Compost. Compos. Sci. Util. 2022, 30, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Chen, G.; Yan, B.; Cheng, Z.; Mu, L. Co-Composting of Cattle Manure and Wheat Straw Covered with a Semipermeable Membrane: Organic Matter Humification and Bacterial Community Succession. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 32776–32789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Zou, X.; Cheng, T.; Li, J. Aerobic Co-Composting of Mature Compost with Cattle Manure: Organic Matter Conversion and Microbial Community Characterization. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, G.S.; Weindorf, D.C.; Mona-liza, C.S.; Ribeiro, B.T.; Chakraborty, S.; Li, B.; Weindorf, W.C.; Acree, A.; Guilherme, L.R.G. Prediction of Compost Organic Matter via Color Sensor. Waste Manag. 2024, 185, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, V.T.; Antonio Pasqualini, A.; Maria Roncato Duarte, K. Electrical Conductivity, pH and Potential Acidity in Soil Fertilized with Poultry Litter Compost. Bol. Ind. Anim. (Impr.) 2014, 71, 39. Available online: https://bia.iz.sp.gov.br/index.php/bia/article/view/411 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Parsa, N.; Khajouei, G.; Masigol, M.; Hasheminejad, H.; Moheb, A. Application of Electrodialysis Process for Reduction of Electrical Conductivity and COD of Water Contaminated by Composting Leachate. Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 4, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, W.; Han, F. Expression and Characterization of a Thermotolerant and pH-Stable Hyaluronate Lyase from Thermasporomyces Composti DSM22891. Protein Expr. Purif. 2021, 182, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemimajd, K.; Farani, T.; Jamaati-e-Somarin, S. Effect of Elemental Sulphur and Compost on pH, Electrical Conductivity and Phosphorus Availability of One Clay Soil. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rabaiai, A.; Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Al-Ismaily, S.; Janke, R.; Al-Alawi, A.; Al-Kindi, M.; Bol, R. Biochar pH Reduction Using Elemental Sulfur and Biological Activation Using Compost or Vermicompost. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 401, 130707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, K.; Gao, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Deng, J.; Zhan, Y.; Li, J.; Li, R. Regulating pH and Phanerochaete Chrysosporium Inoculation Improved the Humification and Succession of Fungal Community at the Cooling Stage of Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Chen, Q.; Quan, H.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T. Combined Treatment for Chicken Manure and Kitchen Waste Enhances Composting Effect by Improving pH and C/N. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 16, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiyati, S.; Priyambada, I.B.; Zahra, S.A.F.; Pradhana, D.R.; Julianggara, M.I.; Febriana, T.F.; Putri, J.N.A.; Saputra, M.N. Comparative Analysis of Composting with Ecoenzymes and Bioactivator MOL Based on Parameters of pH, Temperature, and Water Content. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 605, p. 03054. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, T.B. Effect of Turning on Moisture Content in Sewage Sludge Composting. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 777, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubova, G.; Kavetskiy, A.; Prior, S.A.; Allen Torbert, H. Application of Neutron-Gamma Analysis for Determining Compost C/N Ratio. Compos. Sci. Util. 2019, 27, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, B.; Mnkeni, P. Bio-Optimization of the Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio for Efficient Vermicomposting of Chicken Manure and Waste Paper Using Eisenia Fetida. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 16965–16976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archanjo, B.S.; Mendoza, M.E.; Albu, M.; Mitchell, D.R.; Hagemann, N.; Mayrhofer, C.; Mai, T.L.A.; Weng, Z.; Kappler, A.; Behrens, S. Nanoscale Analyses of the Surface Structure and Composition of Biochars Extracted from Field Trials or after Co-Composting Using Advanced Analytical Electron Microscopy. Geoderma 2017, 294, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducasse, V.; Watteau, F.; Kowalewski, I.; Ravelojaona, H.; Capowiez, Y.; Peigné, J. The Amending Potential of Vermicompost, Compost and Digestate from Urban Biowaste: Evaluation Using Biochemical, Rock-Eval® Thermal Analyses and Transmission Electronic Microscopy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 22, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Yahuitl, V.; Zarco-González, K.E.; Toriz-Nava, A.L.; Hernández, M.; Velázquez-Fernández, J.B.; Navarro-Noya, Y.E.; Luna-Guido, M.; Dendooven, L. The Archaeal and Bacterial Community Structure in Composted Cow Manures Is Defined by the Original Populations: A Shotgun Metagenomic Approach. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1425548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, J.S.; Natarajan, A.; Nisha, K.; Saleena, L.M. Compost Samples from Different Temperature Zones as a Model to Study Co-Occurrence of Thermophilic and Psychrophilic Bacterial Population: A Metagenomics Approach. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Sun, W.; Jin, D.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, P.; Ma, J. Effect of Composting on the Conjugative Transmission of Sulfonamide Resistance and Sulfonamide-Resistant Bacterial Population. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, M.A.; Gilardi, G.; Pugliese, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Garibaldi, A. An Assessment of the Modulation of the Population Dynamics of Pathogenic Fusarium Oxysporum f. Sp. Lycopersici in the Tomato Rhizosphere by Means of the Application of Bacillus Subtilis QST 713, Trichoderma Sp. TW2 and Two Composts. Biol. Control 2020, 142, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanajima, D.; Aoyagi, T.; Hori, T. Dead Bacterial Biomass-Assimilating Bacterial Populations in Compost Revealed by High-Sensitivity Stable Isotope Probing. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albino, R.; Taraba, J.; Marcondes, M.; Eckelkamp, E.; Bewley, J. Comparison of Bacterial Populations in Bedding Material, on Teat Ends, and in Milk of Cows Housed in Compost Bedded Pack Barns. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safianowicz, K.; Bell, T.L.; Kertesz, M.A. Bacterial Population Dynamics in Recycled Mushroom Compost Leachate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 5335–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Elemental Composition (wt. %) | C/N | ASH (%) | 1 HHV (MJ/kg) | pH | 2 EC (mS cm−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | O | N | S | ||||||

| Sugar filter mud | 19.59 | 3.94 | 16.52 | 1.10 | 3.58 | 17.80 | 56.13 | 8.93 | 6.82 | 1.38 |

| sugarcane bagasse | 44.16 | 5.78 | 47.96 | 0.55 | 0.23 | 80.79 | 1.32 | 17.26 | 4.67 | — |

| Parameter | Method/Instrument |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Digital thermometer |

| pH | Portable pH meter |

| Moisture content | Vacuum oven method |

| 1 EC | Conductivity meter |

| 2 OM | Potassium dichromate titration |

| 3 TKN | Selenium-catalyzed digestion method |

| Sample ID | ACE | Chao 1 | Shannon | Simpson | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 3,890,615.74 ± 748,195.36 | 3,782,147.96 ± 839,472.16 | 13.48 ± 0.28 | 1.0000 | 0.97 ± 0.02 |

| b | 4,027,159.36 ± 362,947.81 | 3,817,859.26 ± 492,685.73 | 13.27 ± 0.37 | 1.0000 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| c | 3,442,816.57 ± 915,827.43 | 3,274,298.15 ± 157,934.82 | 13.20 ± 0.35 | 1.0000 | 0.95 ± 0.04 |

| d | 3,725,964.18 ± 284,631.95 | 3,795,162.74 ± 628,417.59 | 13.48 ± 0.28 | 1.0000 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| e | 4,038,261.47 ± 576,218.49 | 3,949,876.51 ± 374,196.28 | 13.29 ± 0.35 | 1.0000 | 0.95 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Luo, M.; Li, S.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y. Mangrove-Derived Microbial Consortia for Sugar Filter Mud Composting and Biofertilizer Production. Sustainability 2026, 18, 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010488

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Tang X, Luo M, Li S, Xue Y, Wang Z, Feng Y. Mangrove-Derived Microbial Consortia for Sugar Filter Mud Composting and Biofertilizer Production. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010488

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yingying, Xiongxian Zhang, Yinghui Wang, Xingying Tang, Mengyuan Luo, Shangze Li, Yuyang Xue, Zhijie Wang, and Yiming Feng. 2026. "Mangrove-Derived Microbial Consortia for Sugar Filter Mud Composting and Biofertilizer Production" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010488

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Tang, X., Luo, M., Li, S., Xue, Y., Wang, Z., & Feng, Y. (2026). Mangrove-Derived Microbial Consortia for Sugar Filter Mud Composting and Biofertilizer Production. Sustainability, 18(1), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010488