Walking, Jogging, and Cycling: What Differs? Explainable Machine Learning Reveals Differential Responses of Outdoor Activities to Built Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research History of Healthy Streets

2.2. Measurement of PA

2.3. Nonlinear Associations Between Built Environment and PA

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.2.1. Motion GPS Trajectories

3.2.2. Streets and Roads

3.2.3. Street View Images

3.2.4. Other Datasets

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variables

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.4. Methods

3.4.1. Random Forest Model

3.4.2. Interpretation Model

3.4.3. Research Framework

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Walking GPS Trajectories

4.1.2. Jogging GPS Trajectories

4.1.3. Cycling GPS Trajectories

4.2. Model Training and Evaluation

4.3. BE Variable Importance

4.4. Nonlinear Associations of BE Variables

4.4.1. The Variables of Accessibility

4.4.2. The Variables of Vitality

4.4.3. The Variables of Attraction

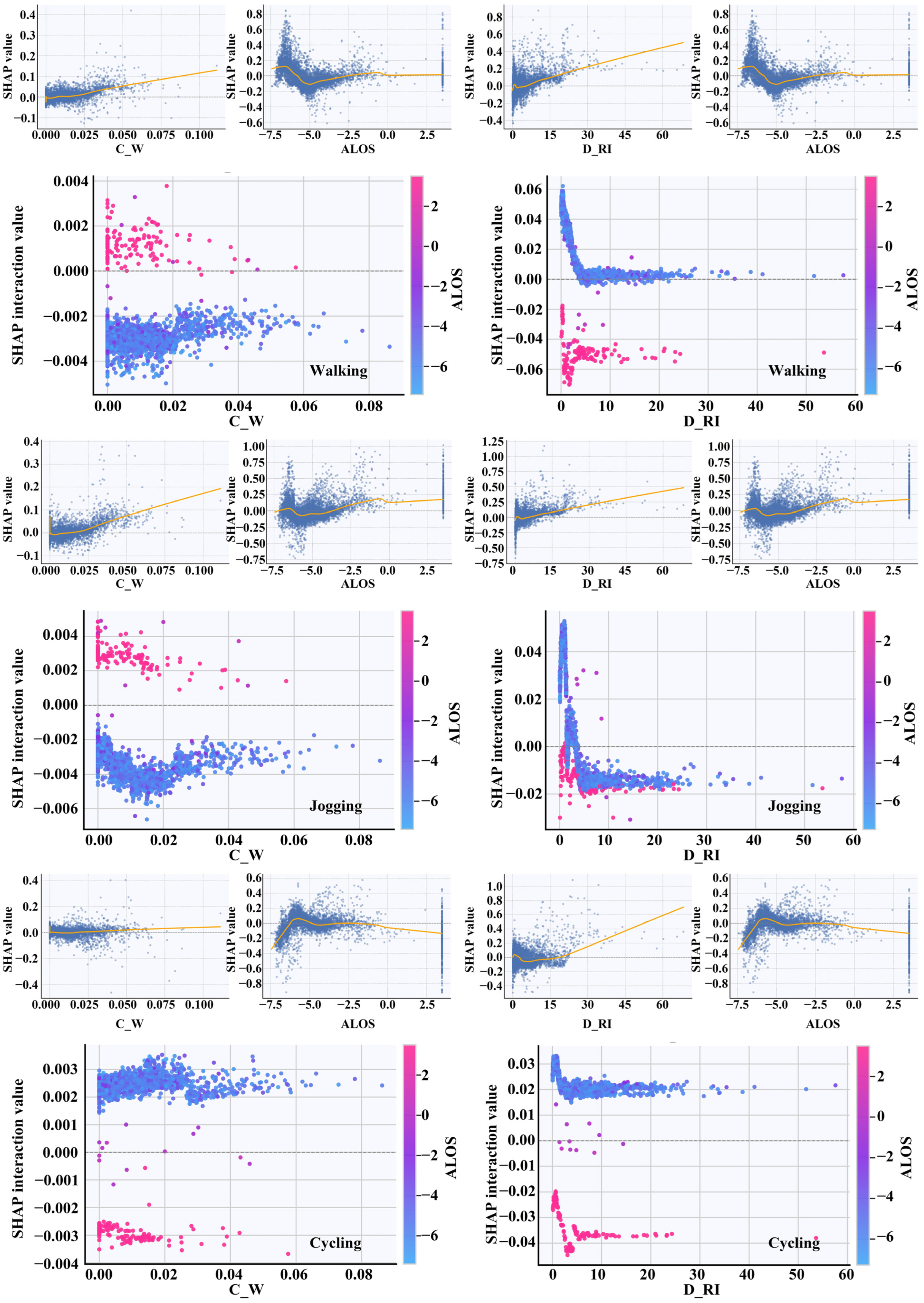

4.5. Interaction Effects Among BE Variables

4.5.1. Overall Analysis

4.5.2. Interaction Analysis

- (1)

- Accessibility–vitality variable pairs

- (2)

- Vitality–attractiveness variable pairs

- (3)

- Attractiveness–accessibility variable pairs

5. Discussion

5.1. Comprehensive Interpretation of BE Affecting Outdoor Activities

5.1.1. Influence of BE on Walking Behaviors

5.1.2. Influence of BE on Jogging Behaviors

5.1.3. Influence of BE on Cycling Behaviors

5.1.4. Contrasting BE Impacts Across Three Outdoor Activities

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cleven, L.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Nigg, C.R.; Woll, A. The Association between Physical Activity with Incident Obesity, Coronary Heart Disease, Diabetes and Hypertension in Adults: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies Published after 2012. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (Ed.) Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-005915-3. [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo Cruz, B.; Ahmadi, M.; Naismith, S.L.; Stamatakis, E. Association of Daily Step Count and Intensity with Incident Dementia in 78 430 Adults Living in the UK. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Bhuyan, S.S.; Tarimo, C.S.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Chen, N.; Miao, Y. Active Commuting and the Risk of Obesity, Hypertension and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e005838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban and Transport Planning Pathways to Carbon Neutral, Liveable and Healthy Cities; a Review of the Current Evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Fan, J.; Peng, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Fei, Y. Systematic Review of Nonlinear Associations between the Built Environment and Walking in Older Adults. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, H. Spatially Varying Effects of Street Greenery on Walking Time of Older Adults. IJGI 2021, 10, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Lin, R.; Liu, J. Building Running-Friendly Cities: Effects of Streetscapes on Running Using 9.73 Million Fitness Tracker Data in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, H.; Ma, X. Effects of Urban Green Exercise on Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1677223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šemrov, D.; Rijavec, R.; Lipar, P. Dimensioning of Cycle Lanes Based on the Assessment of Comfort for Cyclists. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; De Vos, J.; Zhao, P.; Yang, M.; Witlox, F. Examining Non-Linear Built Environment Effects on Elderly’s Walking: A Random Forest Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 88, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General; United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Active Design. Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design; Center for Active Design: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Rubio, O.; Daher, C.; Fanjul, G.; Gascon, M.; Mueller, N.; Pajín, L.; Plasencia, A.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Thondoo, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban Health: An Example of a “Health in All Policies” Approach in the Context of SDGs Implementation. Glob Health 2019, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, X.; Lin, W. Environment and Sports. Zhejiang Sport. Sci. 1990, 6, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. A Literature Review: A Collaborative Study on Housing Type, Environment, and Residents’ Health. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1992, 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Guo, C. Design Guidelines for Active Living: Western Experience. New Archit. 2005, 6, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Li, L. New Perspectives on Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Strategies and Research. Chin. J. Prev. Control. Chronic Dis. 2009, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. Environment, Walking and Health: An Evolutionary, Social-Ecological View. Sport. Sci. Res. 2009, 30, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J. On the Forming of Health-oriented Urban Space. Mod. Urban Res. 2009, 24, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Xinghua News Agency. Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, S. Urban street health service function based on mobile fitness data. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Bian, Q.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, B. A Research on the Correlation between PhysicalActivity Performance and Thermal Comfortable ofUrban Park in Cold Region. Chin. Landescape Archit. 2019, 35, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, N.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Dai, H. A Review on the Application Research of Trajectory Data Mining in Urban Cities. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2015, 17, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Alberico, C.; Zweig, M.; Carter, A.; Hughey, S.M.; Huang, J.-H.; Schipperijn, J.; Floyd, M.F.; Hipp, J.A. Use of Accelerometry and Global Positioning System (GPS) to Describe Children’s Park-Based Physical Activity among Racial and Ethnic Minority Youth. J. Urban Health 2025, 102, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantz, K.H.; Meredith, H.R.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Metcalf, C.J.E.; Grenfell, B.T.; Giles, J.R.; Mehta, S.; Solomon, S.; Labrique, A.; Kishore, N.; et al. The Use of Mobile Phone Data to Inform Analysis of COVID-19 Pandemic Epidemiology. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Batty, M.; Manley, E.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F.; Schmitt, G. Variability in Regularity: Mining Temporal Mobility Patterns in London, Singapore and Beijing Using Smart-Card Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free Report: Newzoo Global Mobile Market Report 2021|Free Version. Newzoo 2021. Available online: https://newzoo.com/resources/trend-reports/newzoo-global-mobile-market-report-2021-free-version (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Meng, C. Analysis of the Current Situation Andoptimization Suggestions of NinghaiNational Trail Based on Volunteeredgeographic Information Data. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L. Evaluation and Optimization of Urban Greenways in Hangzhou Based on Trajectory Data of Physical Activities. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Cao, X.; Næss, P. Applying Gradient Boosting Decision Trees to Examine Non-Linear Effects of the Built Environment on Driving Distance in Oslo. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 110, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Wang, J.; Cao, X. Exploring the Non-Linear Associations between Spatial Attributes and Walking Distance to Transit. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Built Environment Restrained Traffic Carbon Emissions and Policy Implications. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Helbich, M.; Lu, Y.; He, D.; Ettema, D.; Chen, L. Examining Non-Linear Associations between Built Environments around Workplace and Adults’ Walking Behaviour in Shanghai, China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 155, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, M.; Li, D. Bike-Sharing or Taxi? Modeling the Choices of Travel Mode in Chicago Using Machine Learning. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 79, 102479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhang, T.; Ai, T.; Wang, Y. Characterizing the Activity Patterns of Outdoor Jogging Using Massive Multi-Aspect Trajectory Data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 95, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Sheng, J.; Li, Q.; Ban, P. The Nonlinear Influence of Built Environment on Multi Period Running Activities in Streets Based on Random Forest Model: A Case Study of Shenzhen. Trop. Geogr. 2025, 45, 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Hu, J. Exploring Nonlinear Effects of Built Environment on Jogging Behavior Using Random Forest. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 156, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Towards Resilient Urban Design: Revealing the Impacts of Built Environment on Physical Activity amidst Climate Change. Buildings 2025, 15, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- stataiml. Thresholds for Detecting Multicollinearity. Available online: https://stataiml.com/posts/60_multicollinearity_threshold_ml/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Yang, W.; Fei, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y. Unraveling Nonlinear and Interaction Effects of Multilevel Built Environment Features on Outdoor Jogging with Explainable Machine Learning. Cities 2024, 147, 104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzdugan, S. Random Forest XGBoost vs LightGBM vs CatBoost: Tree-Based Models Showdown. Medium 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@sebuzdugan/random-forest-xgboost-vs-lightgbm-vs-catboost-tree-based-models-showdown-d9012ac8717f (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Twardzik, E.; Falvey, J.R.; Clarke, P.J.; Freedman, V.A.; Schrack, J.A. Public Transit Stop Density Is Associated with Walking for Exercise among a National Sample of Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, M.; Sieben, A. The Connection between Stress, Density, and Speed in Crowds. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, W.; Qiu, B.; Wang, H.; Qiu, W. Assessing Impacts of Objective Features and Subjective Perceptions of Street Environment on Running Amount: A Case Study of Boston. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Moudon, A.V.; Zhou, C.; Stewart, O.T.; Saelens, B.E. Light Rail Leads to More Walking around Station Areas. J. Transp. Health 2017, 6, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Mi, Z.; Coffman, D.; Meng, J.; Liu, D.; Chang, D. The Role of Bike Sharing in Promoting Transport Resilience. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2022, 22, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, I.; Sobhan, S.; Klaprat, N.; George, T.; Vik, N.; Prowse, D.; Collett, J.; McGavock, J. Urban Cycling-Specific Active Transportation Behaviour Is Sensitive to the Fresh Start Effect: Triangulating Observational Evidence from Real World Data. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.; Datta, G.D.; Chinerman, D.; Kakinami, L.; Mathieu, M.-E.; Henderson, M.; Barnett, T.A. Associations of Neighborhood Walkability with Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity: An Application of Compositional Data Analysis Comparing Compositional and Non-Compositional Approaches. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Inoue, S.; Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, H.; Takamiya, T.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Hikihara, Y.; Tanaka, S. Lower Youth Steps/Day Values Observed at Both High and Low Population Density Areas: A Cross-Sectional Study in Metropolitan Tokyo. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.D.; Xiao, W.; Wen, M.; Wei, R. Walkability, Land Use and Physical Activity. Sustainability 2016, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, B.; Ta, N.; Zhou, K.; Chai, Y. Does Street Greenery Always Promote Active Travel? Evidence from Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Yin, H.; Bai, Z.; Yin, J.; Xia, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D. Walking, Jogging or Cycling? Exploring the Associations between Campus Greenway Environment and Physical Activity Using Large-Scale Trajectory Data. People Nat. 2025, 7, 2678–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Yu, B.; Li, P.; Liang, P. Spatially Varying Impacts of the Built Environment on Physical Activity from a Human-Scale View: Using Street View Data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1021081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki-Opas, T.E.; Borodulin, K.; Valkeinen, H.; Stenholm, S.; Kunst, A.E.; Abel, T.; Härkänen, T.; Kopperoinen, L.; Itkonen, P.; Prättälä, R.; et al. The Contribution of Travel-Related Urban Zones, Cycling and Pedestrian Networks and Green Space to Commuting Physical Activity among Adults—A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study Using Geographical Information Systems. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Schindler, M.; Belcher, R.N. Walking Time Is a Major Barrier to Accessing Urban Ecosystems Globally. npj Urban Sustain. 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoelder, M.; Schoofs, M.C.A.; Raaphorst, K.; Lakerveld, J.; Wagtendonk, A.; Hartman, Y.A.W.; van der Krabben, E.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Lifelines Corona Research Initiative. A Positive Neighborhood Walkability Is Associated with a Higher Magnitude of Leisure Walking in Adults upon COVID-19 Restrictions: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, E.Y.; Lee, N.H.; Choi, C.G. Relationship between Land Use Mix and Walking Choice in High-Density Cities: A Review of Walking in Seoul, South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Liu, X.; Peng, B.; Wang, T.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y. Nonlinear and Threshold Effects of Built Environment on Older Adults’ Walking Duration: Do Age and Retirement Status Matter? Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1418733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Cao, J.; Sun, B.; Liu, J. Exploring Built Environment Correlates of Walking for Different Purposes: Evidence for Substitution. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Park, H.; Hong, E.; Lee, J.; Kwon, N. Predicting Effects of Built Environment on Fatal Pedestrian Accidents at Location-Specific Level: Application of XGBoost and SHAP. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 166, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deelen, I.; Janssen, M.; Vos, S.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Ettema, D. Attractive Running Environments for All? A Cross-Sectional Study on Physical Environmental Characteristics and Runners’ Motives and Attitudes, in Relation to the Experience of the Running Environment. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y. Association and Interaction between Built Environment and Outdoor Jogging Based on Crowdsourced Geographic Information. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, P. Meta-analysis on associations between the built environment and mobile physical activity using volunteered geographic information. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wang, X.; Lyu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Heinen, E.; Sun, Z. Understanding Cycling Distance According to the Prediction of the XGBoost and the Interpretation of SHAP: A Non-Linear and Interaction Effect Analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Sánchez, F.S.; Valenzuela-Montes, L.M.; Abarca-Álvarez, F.J. Evidence of Green Areas, Cycle Infrastructure and Attractive Destinations Working Together in Development on Urban Cycling. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-Y.; Paulsen, M.; Nielsen, O.A.; Jensen, A.F. Analysis of Cycling Accessibility Using Detour Ratios—A Large-Scale Study Based on Crowdsourced GPS Data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yu, S.; Ai, L.; Dai, J.; Chung, C.K.L. The Built Environment, Purpose-Specific Walking Behaviour and Overweight: Evidence from Wuhan Metropolis in Central China. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2024, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Non-Linear Effects of the Built Environment and Social Environment on Bus Use among Older Adults in China: An Application of the XGBoost Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Namkung, O.S.; Ko, J.; Yao, E. Cycling Distance and Detour Extent: Comparative Analysis of Private and Public Bikes Using City-Level Bicycle Trajectory Data. Cities 2024, 151, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Q.; Wei, W.; Liu, G.; Liu, M. Landscape Scene Sequences of Park View Elements Facilitate Walking, Jogging, and Running: Evidence from 3 Parks in Shanghai. Buildings 2025, 15, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50220-95; Urban Road Traffic Planning and Design Code. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Beijing, China, 1995.

- Cerin, E.; Sallis, J.F.; Salvo, D.; Hinckson, E.; Conway, T.L.; Owen, N.; van Dyck, D.; Lowe, M.; Higgs, C.; Moudon, A.V.; et al. Determining Thresholds for Spatial Urban Design and Transport Features That Support Walking to Create Healthy and Sustainable Cities: Findings from the IPEN Adult Study. Lancet Glob Health 2022, 10, e895–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, J.; Ding, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Song, Z.; Wu, Y. Quality Assessment of Cycling Environments around Metro Stations: An Analysis Based on Access Routes. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Gundersen, V.; Scott, S.L.; Barton, D.N. Bias and Precision of Crowdsourced Recreational Activity Data from Strava. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, T.; Ivanovic, B.; King, A.C.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L.; Leskovec, J. Countrywide Natural Experiment Links Built Environment to Physical Activity. Nature 2025, 645, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Guan, H.; Yan, H.; Hao, M. Community Environment, Psychological Perceptions, and Physical Activity among Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.Y.; Goggins, W.B.; Mo, P.K.H.; Chan, E.Y.Y. The Effect of Temperature on Physical Activity: An Aggregated Timeseries Analysis of Smartphone Users in Five Major Chinese Cities. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Road Grade | Road Width (m) | Buffer Zone Distance (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Main road | 45–55 | 55 |

| Secondary road | 40–50 | 50 |

| Branch line | 15–30 | 30 |

| Category of Variable | Name of Variable | Abbr. | Description or Calculation | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Bus stop density | D_BS | Number of bus stops/TAZ area size | points/m |

| Road intersection density | D_RI | Number of intersections/TAZ area size | points/km | |

| Distance to nearest subway entrance | D_SBE | Distance from the nearest subway entrance to TAZ centroid | m | |

| Walking continuity | C_W | / | ||

| Vitality | Land use mix | LUM | / | |

| Population density | D_P | Population/TAZ area | persons/km2 | |

| Retail store density | D_RS | Number of retail stores/TAZ area size | points/m | |

| Attraction | Accessibility of large open spaces | ALOS | Distance to large open spaces (standardized) | / |

| Sky openness | SO | SO = SO_x/i/n, (i = 1, …, n) The proportion of sky pixels in the i-th sampling point | / | |

| Green view index | GVI | The proportion of vegetation pixels in the i-th sampling point | / | |

| Interface enclosure | IE | The ratio of building height to street width | / | |

| Building continuity | C_B | / |

| Variable | VIF | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| D_RS | 1.065 | 0.939 |

| ALOS | 1.079 | 0.926 |

| LUM | 1.154 | 0.866 |

| D_RI | 1.194 | 0.838 |

| D_BS | 1.287 | 0.777 |

| D_SBE | 1.323 | 0.756 |

| D_P | 1.368 | 0.731 |

| C_W | 1.538 | 0.650 |

| C_B | 1.543 | 0.648 |

| GVI | 2.016 | 0.496 |

| SO | 2.270 | 0.440 |

| IE | 2.489 | 0.402 |

| Model | Parameters | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N_Estimators | Learning Rate | Max_Depth | RMSE | MAE | R2 | |

| RF | 500 | / | 13 | 0.892 | 0.680 | 0.682 |

| XGBoost | 100 | 0.14 | 6 | 0.929 | 0.695 | 0.655 |

| LightGBM | 400 | 0.04 | 15 | 0.940 | 0.716 | 0.646 |

| Model | Parameters | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N_Estimators | Learning Rate | Max_Depth | RMSE | MAE | R2 | |

| RF | 500 | / | 13 | 0.719 | 0.519 | 0.660 |

| XGBoost | 100 | 0.14 | 6 | 0.750 | 0.524 | 0.631 |

| LightGBM | 400 | 0.04 | 13 | 0.762 | 0.545 | 0.619 |

| Model | Parameters | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N_Estimators | Learning Rate | Max_Depth | RMSE | MAE | R2 | |

| RF | 500 | / | 13 | 0.746 | 0.551 | 0.662 |

| XGBoost | 100 | 0.15 | 6 | 0.774 | 0.560 | 0.637 |

| LightGBM | 400 | 0.04 | 19 | 0.797 | 0.590 | 0.615 |

| Activity | Category of Variable | Name of Variable | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycling | Accessibility | D_BS | 30.1% |

| Vitality | LUM | 27.1% | |

| Vitality | D_P | 16.7% | |

| Accessibility | D_SBE | 7.6% | |

| Attraction | ALOS | 5.4% | |

| Accessibility | D_RI | 4.5% | |

| Vitality | D_RS | 1.9% | |

| SUM | 93.3% | ||

| Jogging | Vitality | LUM | 25.7% |

| Accessibility | D_BS | 21.2% | |

| Vitality | D_P | 14.1% | |

| Attraction | ALOS | 10.7% | |

| Accessibility | D_SBE | 7.8% | |

| Accessibility | D_RI | 5.8% | |

| Attraction | SO | 4.3% | |

| SUM | 89.6% | ||

| Walking | Vitality | D_P | 26.3% |

| Accessibility | D_BS | 22.0% | |

| Vitality | LUM | 16.9% | |

| Attraction | ALOS | 9.1% | |

| Accessibility | D_SBE | 8.8% | |

| Accessibility | D_RI | 5.5% | |

| Attraction | SO | 2.7% | |

| SUM | 91.3% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, M.; Zhong, P.; Liu, R. Walking, Jogging, and Cycling: What Differs? Explainable Machine Learning Reveals Differential Responses of Outdoor Activities to Built Environment. Sustainability 2026, 18, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010485

Xiao M, Zhong P, Liu R. Walking, Jogging, and Cycling: What Differs? Explainable Machine Learning Reveals Differential Responses of Outdoor Activities to Built Environment. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010485

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Musong, Peng Zhong, and Runjiao Liu. 2026. "Walking, Jogging, and Cycling: What Differs? Explainable Machine Learning Reveals Differential Responses of Outdoor Activities to Built Environment" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010485

APA StyleXiao, M., Zhong, P., & Liu, R. (2026). Walking, Jogging, and Cycling: What Differs? Explainable Machine Learning Reveals Differential Responses of Outdoor Activities to Built Environment. Sustainability, 18(1), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010485