1. Introduction

Plastic litter pollution is a rapidly evolving global environmental issue with significant consequences for ecosystem health, human well-being, and sustainable development. More than 460 million tonnes of plastic are produced annually, and less than 10% are ever recycled, producing vast mismanagement that disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries [

1,

2]. Environmentally unfriendly waste disposal, including open dumping, open burning, and direct effluent release into water bodies, facilitates the easy entry of chemicals and plastic-bound contaminants into the terrestrial and aquatic food chains [

3,

4]. The same entry routes facilitate habitat degradation and compromise water security by promoting leachate percolation, surface runoff, and atmospheric deposition of toxic by-products, such as dioxins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and microplastics [

5,

6].

There is also rapid urbanisation, poor waste infrastructure, and heavy surface water use across the Caribbean region, which exacerbate the plastic pollution hazard. Empirical analysis of household waste practices is, nevertheless, scant, particularly in mainland Caribbean nations like Guyana. Although regional reports show policy shortfall and waste streams [

7,

8]. Few analyse the role of socioeconomic heterogeneity on disposal behaviours, and none relate these to water quality hazards in Guyana’s typical hydrology.

Freshwater system contamination is of particular interest to nations like Guyana, where over 90% of the country relies on surface and ground water for industrial, agricultural, and household uses [

3,

4]. Guyana’s flat coastal plain and intricate river network make the nation very vulnerable to plastic-borne contamination, especially in the context of increasing urbanisation and consumption patterns without a corresponding investment in facilitative waste infrastructure [

5,

6]. While these risks are identified in national strategies, such as the Low Carbon Development Strategy 2030 and the National Solid Waste Management Strategy (2013–2024), they are exacerbated by fragmented service provision, weak enforcement, and socioeconomically unequal access to waste collection [

6].

Additional evidence has confirmed that household waste management practice is strongly moderated by socioeconomics, i.e., income, education, and employment status [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Higher educated and affluent families will always use formal disposal sites and adapt their green behaviours, and poor communities use high-risk alternatives due to economy, access to services, or lack of choice, following the environmental Kuznets curve [

16,

17,

18]. Double whammy: poor people are both cause and disproportionately impacted victims of environmental deterioration, a bitter rejection of environmental justice values underlying sustainability plans such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [

19].

Despite such global evidence, empirical evidence of socioeconomic status as a cause of plastic waste mismanagement and water quality risks in the Caribbean is lacking, and virtually nonexistent in Guyana. The majority of studies in the country are either policy studies or waste composition studies, but some have addressed the behavioural, environmental, and equity factors [

7,

8]. Such limited evidence hinders the development of targeted, evidence-informed interventions grounded in circular-economy policy and in regional and local agendas for transitioning to sustainability.

This study fills this crucial knowledge gap by investigating the socioeconomic drivers of toxic plastic waste dumping in four villages in Guyana, Mon Repos, Lusignan, De Endragt, and Good Hope, and water resource quality impacts. This study does not claim generalisability beyond the four surveyed communities. Instead, it offers a foundational, context-specific baseline to inform future mixed-methods research and pilot interventions. Using household survey data (N = 384), we investigate relationships between education, income, labour force status, age, and household status and incorrect waste disposal behaviour (i.e., dumping or burning). We also investigated the geographic congruence between these practices and measurable waste production as a means of controlling water pollution. Although water quality monitoring was not incorporated into the current study, it provides explanatory background for upscaling to future large-scale research and policy interventions aimed at enhancing environmental resilience and social justice in Guyana’s development towards sustainable water and waste management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study focuses on four communities in Guyana: Mon Repos, Lusignan, De Endragt, and Good Hope. These communities were selected to represent a range of urban and peri-urban settings with varying levels of access to formal waste management services. Each community faces unique challenges related to plastic waste management and potential impacts on local water resources (

Figure 1).

2.2. Sample Population Selection Method

The sample for this research was selected based on a multi-stage sampling strategy to realize representation according to key demographic and geographic characteristics relevant to plastic waste management in domestic households in Guyana, recruiting residents of four purposively selected areas, Mon Repos and Lusignan representing urban areas with comparatively better access to municipal services, and De Endragt and Good Hope representing peri-urban areas with underdeveloped formal waste collection infrastructure, to realize the entire spectrum of waste management practice and determinants. In every community, the households were selected by systematic sampling in which the chosen enumerators every nth household along previously marked transects from community maps to achieve geographic representation to have about 96 households per community (384 across all communities) estimated based on standard sample size formulae for descriptive studies with the assumption of a 95% level of confidence, 5% margin, and estimated 50% prevalence of key behaviours. Households were considered for involvement if they had at least one adult resident (18 years or older) responsible for waste management decisions, had resided for at least 6 months, and agreed to participate, excluding commercial properties, temporary accommodations, and institutional accommodations. The sample frame was constructed from recent community registers and rolls of the local government, supplemented by door-to-door reconnaissance in communities that lacked official registers, to create detailed household listings through the joint efforts of enumerators and community leaders. The research achieved a 100% response rate by conducting pre-study interactions with local government authorities and community leaders to outline the study’s purpose and importance.

2.3. Data Collection

For the study, data were collected through a standardised household survey as part of the PROMAR Household Plastic Waste Material Flow Analysis project. The survey instrument gathered comprehensive information on household features, plastic waste generation behaviours, disposal modes, access to waste collection services, and attitudes about service adequacy. Between 21 June and 8 July 2025, a total of 384 valid responses were obtained.

Significant variables collected are:

Demographic information: Education level, employment status, household income, household composition (single income earner, partner, other adult household member)

Domestic waste handling behaviour: Type of plastic products utilised, frequency of use, method of disposal (municipal bins, private company, informal collector, self-disposal by dumping, burning, abandoning)

Service use and attitude: Type of waste collection service used, perceived adequacy of service, collection frequency

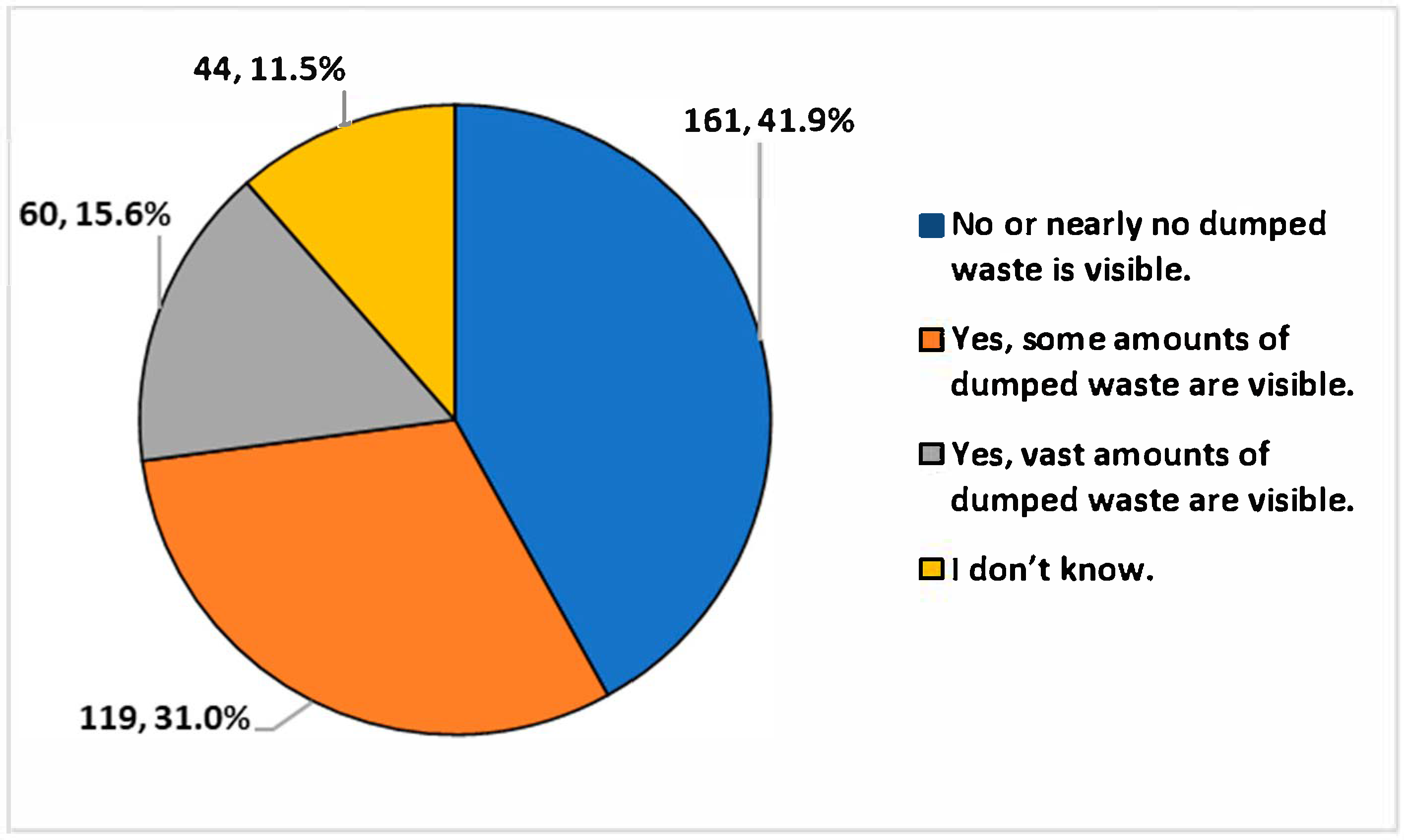

Environmental indicators: Sight of refuse dumped within the adjacent area (rated as ‘No or scarcely any’, ‘Yes, small amounts’, ‘Yes, some amounts’, ‘Yes, massive amounts’, ‘I don’t know’)

While the survey instrument gathered quantitative behavioural and demographic data, it did not include qualitative modules (e.g., open-ended interviews or focus groups) through which cultural, psychological, or institutional drivers of disposal choices may have been revealed. Future iterations of this study should use mixed methods to generate more refined hypotheses about the underlying drivers of waste mismanagement.

The questionnaire was tested in 15 households in a non-study village, Beterverwagting (an adjacent community), for cultural sensitivity and wording. Enumerator training included techniques to reduce social desirability bias. This involved using confidential methods and neutral language.

The “high-risk” label for disposal practices agrees with standard environmental health guidelines. It reflects existing research showing that informal waste burning and open dumping are significant sources of water pollution [

3,

5].

Visible signs of dumped rubbish served as a practical indicator of environmental risk, following community-based methods in areas with limited data [

19,

20]. Although it indirectly measures water quality, visible rubbish buildup closely relates to leachate drainage and runoff issues in low-lying coastal regions, as in the aforementioned study areas.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 28. Descriptive statistics were applied to report the sample population and summarise waste management practices. Cross-tabulations and chi-square tests examined associations between socioeconomic variables and high-risk disposal practices (dumping, burning, abandoning waste). By prioritising bivariate chi-square analysis, a sound research methodology for hypothesis testing, we limit our ability to explore interaction effects or multivariate causality. A more interdisciplinary approach, combining hydrological modelling, cost analysis, and social network theory, could transform this descriptive study into a predictive model for policymakers.

For this study, ‘high-risk disposal practices’ are defined as self-reported disposal methods that have a direct and immediate impact on water quality and the environment. These include: (1) dumping rubbish in unauthorised sites or on open land, (2) burning rubbish in the household garden or on nearby land, and (3) directly dumping rubbish into water bodies or open fields.

To assess the risk to water resources, the presence of dumped waste within the neighbourhood was used as a proxy indicator. Households responding with ‘Yes, some amounts’ or ‘Yes, huge amounts’ of visible dumped waste were classified as living in areas with a higher potential risk of plastic leaching into water bodies.

To identify independent socioeconomic predictors of high-risk plastic waste disposal, a binary logistic regression model was employed using SPSS version 28. The dependent variable was dichotomised into high-risk disposal (1 = practised burning, dumping, or abandonment; 0 = practised low-risk or formal disposal practices). Independent variables included education level (reference: university), employment status (reference: government employer), household income (reference: >GYD

$255,000), age category (reference: 60+ years), and household role (reference: breadwinner). Missing income or education data were excluded by listwise deletion (133 records were excluded), leaving an analytical sample of n = 251. Descriptive statistics, cross-tabulations, and visualisations (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) are based on the full sample of N = 384 households, as these analyses accommodate missing data through valid response counts per item. However, the binary logistic regression model required complete data on all predictor variables; thus, only n = 251 households with complete socioeconomic information were included in the multivariate analysis. This distinction is maintained throughout the Results and Discussion sections to avoid conflation of descriptive and inferential findings. Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and multicollinearity was assessed via variance inflation factors (all VIFs < 2.0, indicating no issues). Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and

p-values (α = 0.05).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Since there was no institutional review board, the research team adhered to the ethical guidelines for social science research as outlined by the University of Guyana’s Faculty of Earth & Environmental Sciences and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Confidential procedures were strictly maintained, with data anonymised and stored using secure, unique identification codes. The research posed minimal risk to participants and included pre-study community-based activities to ensure local engagement and cultural sensitivity. All research processes complied with consideration for Guyanese laws and regulations, and the findings were reported responsibly to protect participant confidentiality and to inform policy and science.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The survey sample included 384 households from the four study communities. Most respondents were female (58.1%), aged 18–24 years (10.2%), and 60 years or over (21.6%). Education levels varied: 31.5% had completed secondary school, 26.8% held university qualifications, and 19.3% chose not to disclose their education level. Employment statuses were reported as 38.8% working for the government, 15.6% for NGOs, 10.4% unemployed, and 12.5% being students (see

Table 1).

Income was distributed as follows: 34.6% of households had incomes between

$85,001 and

$255,000 Guyanese dollars (GYD), while 31.0% of households earned above GYD

$255,000. The remaining households earned GYD

$85,000 or less (19.0%) or did not respond to questions about income (15.4%) (see

Table 1).

Population data also indicate that interventions must include gendered waste management responsibilities and extend to poorer, less educated, and unemployed segments of society, who are statistically more at risk of unhygienic disposal.

3.2. Plastic Waste Disposal and Management Practices

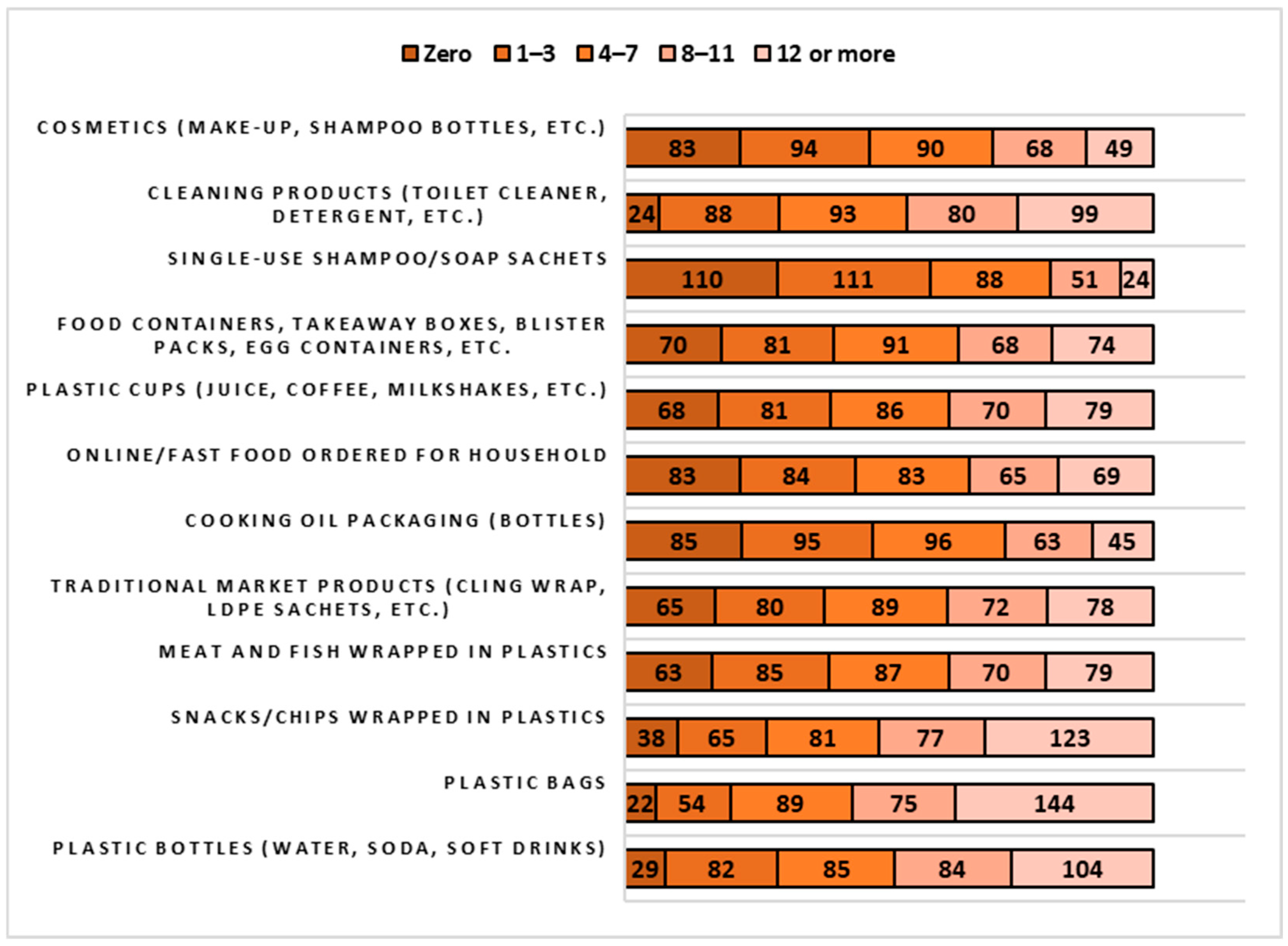

Figure 2 reveals a heavy and structural reliance on single-use plastics, with consumption patterns sharply delineated by socioeconomic status. The ubiquitous use of plastic bags (144 households using 12 or more weekly) and single-use beverage bottles underscores a community-wide ‘throwaway culture’. However, the bimodal distribution for items like cooking oil and sachets is particularly telling. The high consumption of cooking oil bottles reflects its status as a frequent, essential purchase. In stark contrast, the concentration of sachet use (for products like shampoo and soap) among a smaller segment of the population points directly to poverty-driven purchasing habits, in which smaller, cheaper units are preferred despite generating more waste per unit. This divergence is not merely a difference in preferences but a clear indicator of how economic constraints shape both consumption and the subsequent waste stream.

As illustrated in

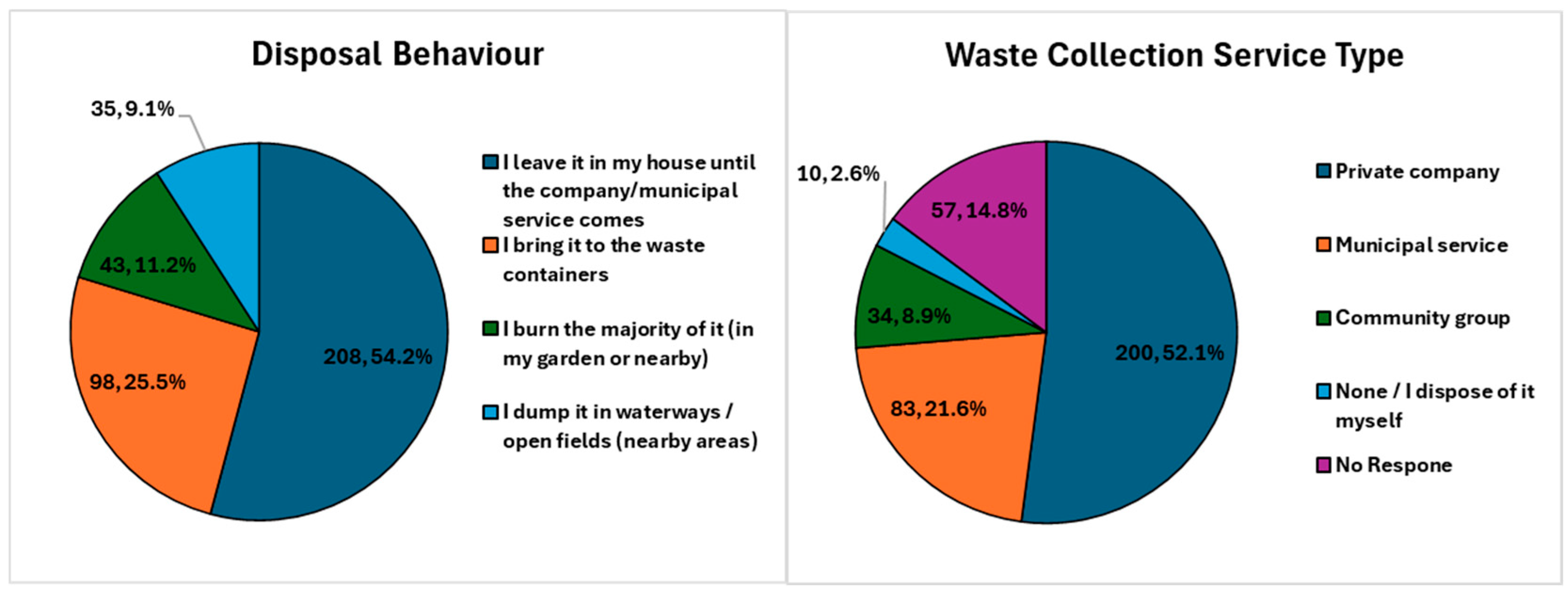

Figure 3, the waste management landscape is characterised by a fragmented, market-driven system. The heavy reliance on private sector collection (52.1%), more than double the use of municipal services (21.6%), creates a critical access barrier. This is because private services are typically fee-based, effectively excluding low-income households from formal disposal routes. The data visualises the direct consequence of this exclusion: the high-risk practices of burning (11.2%) and dumping (9.1%) are not merely individual choices but are rational, if detrimental, responses to this infrastructural and economic failure. The minimal municipal footprint highlights a systemic underinvestment in public services, leaving a vacuum that exacerbates environmental injustice.

The behaviour data for garbage disposal indicate a strongly ranked pattern of response to the breakdown of official collection: the passive restraint default is observed, and 208 houses (54.2%) reported keeping garbage in the house until municipal or private collection resumes, indicating reliance on, but vulnerability to, unstable networks of collection. A significant minority (25.5%, n = 98) actively sends garbage to suitable containers, indicating agency when infrastructure is in place. In contrast, the 11.2% (n = 43) who burn and 9.1% (n = 35) who dump in open spaces or bodies of water are predominantly from socioeconomically poor households. Such hazardous practices are not isolated incidents but a direct result of institutional service failure, showing how infrastructural inadequacy causally leads to environmental degradation in the targeted water-sensitive coastal communities (see

Figure 3).

3.3. Perceptions of Service Adequacy

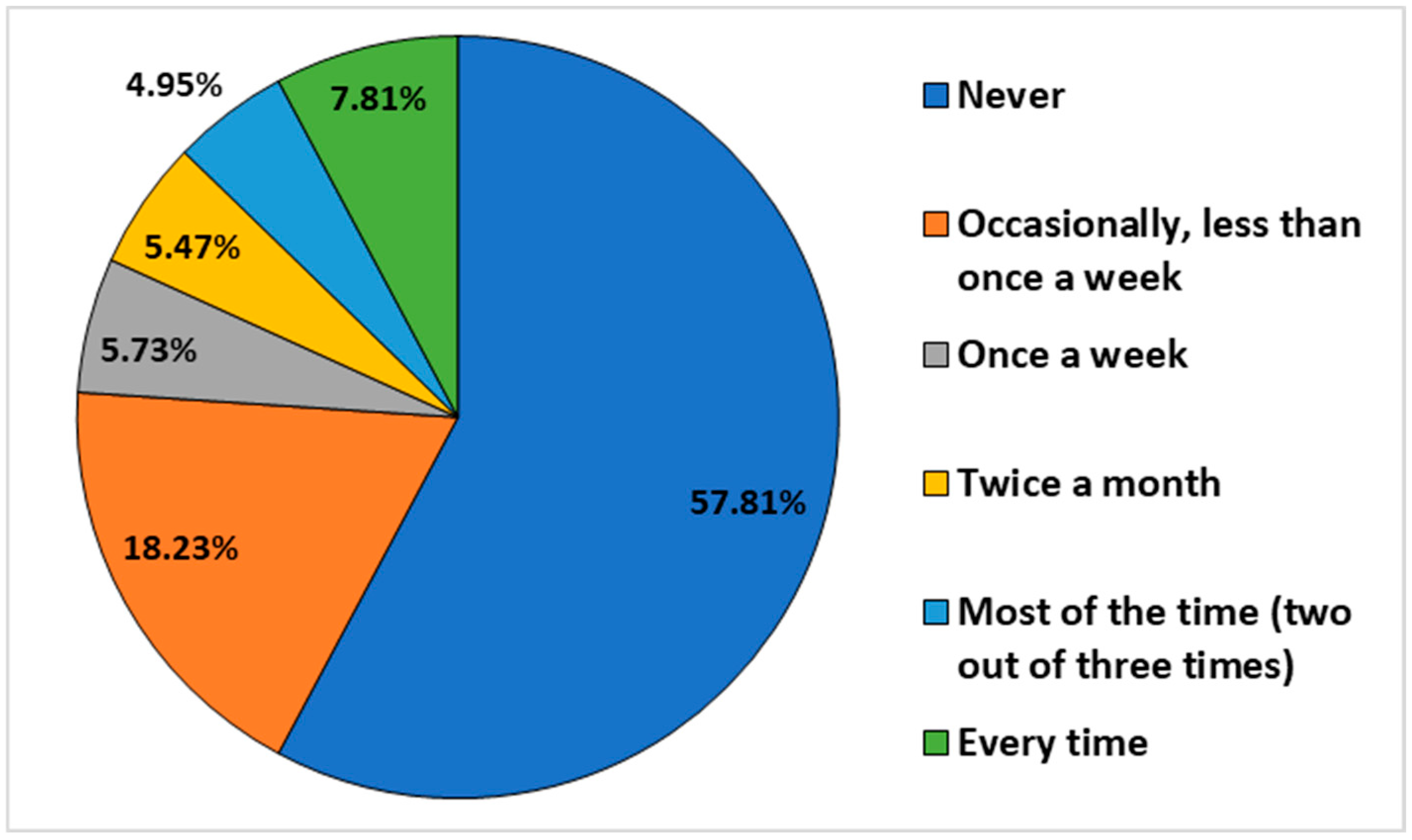

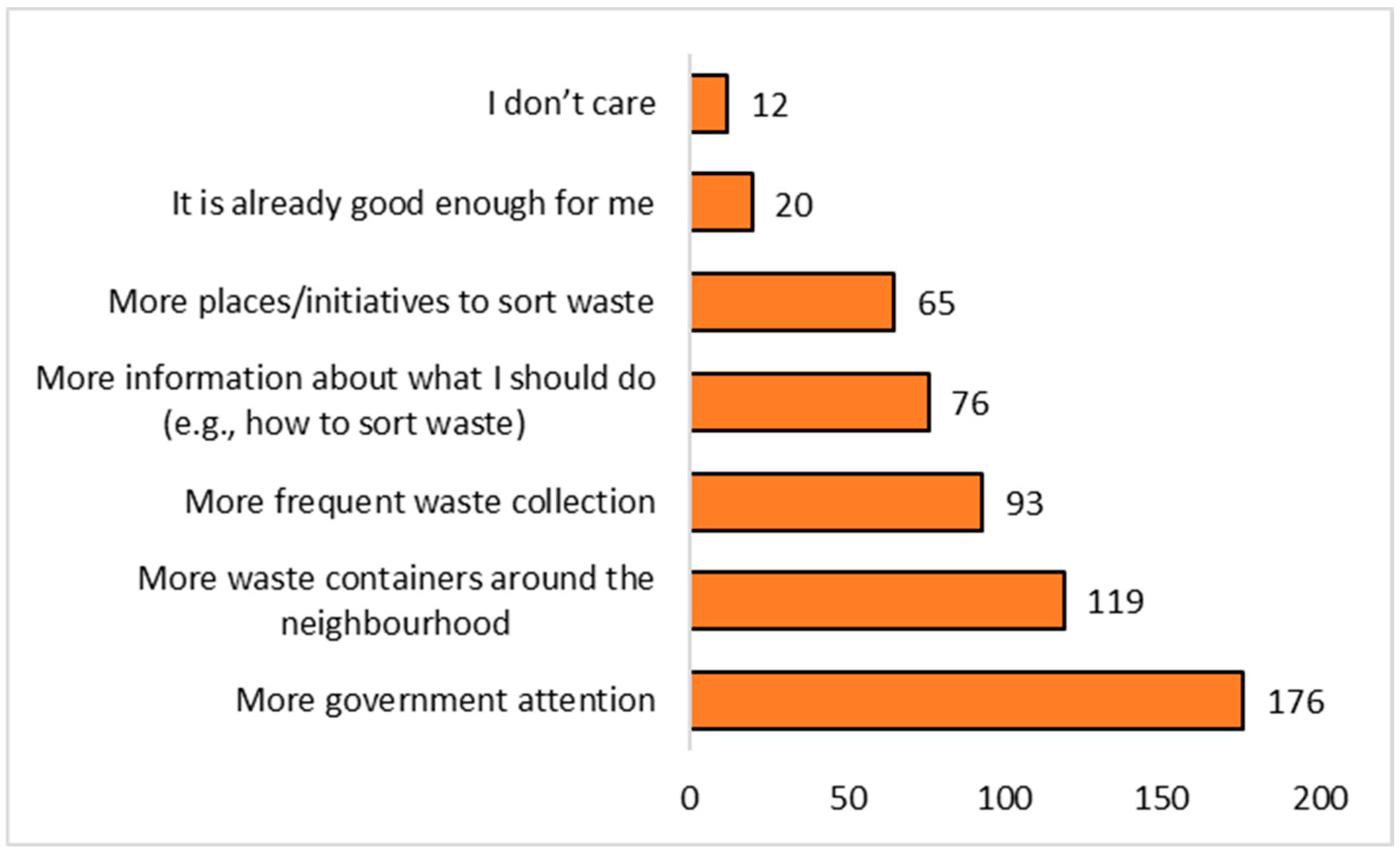

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 together demonstrate that communities are not apathetic towards waste management but are pragmatically aware of systemic failures. While

Figure 4 shows that a majority (57.8%) report adequate service, a significant minority (42.2%) experience unreliable collection, a figure that aligns with the observed reliance on high-risk disposal methods. Crucially,

Figure 5 reveals the community’s diagnosis of the problem. The most demanded solutions, ‘More government attention’ (176 responses) and ‘More waste bins’ (119 responses), are calls for robust, physical infrastructure and greater institutional oversight, not simply awareness campaigns. This underscores that the public recognises the solution lies in systemic investment and governance, not in changes to individual behaviour alone.

3.4. Visibility of Dumped Waste

The prevalence of visible waste, shown in

Figure 6, confirms that environmental degradation is a current and widespread reality for these communities. With nearly half (46.6%) of all households reporting ‘some’ or ‘vast’ amounts of dumped refuse, pollution is normalised rather than exceptional. This high visibility is critical; it acts as a feedback loop, where the sight of existing waste legitimises further dumping behaviour for residents who lack alternatives. This normalisation of pollution in the lived environment directly underpins the inferred risk to water resources, as these visible accumulations are the very sources of leachate and runoff.

3.5. Link Between Disposal Method and Environmental Waste Visibility

The linkage between disposal behaviour and visible environmental impact is significant to the point where it explains the probability of water contamination.

Table 2 compares disposal behaviour and waste visibility, painting a complex picture. Domestic data indicates that those who use collection services have 49.0% visibility of the waste, the same as those who dispose of it themselves at 48.7%. This finding is that even when waste is sent to a formal or informal collection network, it can still be dumped or burned in the middle zones of the community, creating hotspots of contamination to which everyone living there is exposed. Therefore, the high-risk practice of dumping is not an isolated behavioural failure but a symptom of a structurally deficient waste management system.

3.6. Socioeconomic Determinants of High-Risk Disposal Behaviours

The results suggest that family socioeconomic characteristics are significantly associated with unsafe practices in plastic waste disposal, such as dumping or incineration, or dumping trash at unauthorised sites. Early chi-square tests showed an association. Binary logistic regression provided an explanation of which parameters are significant when other determinants are held constant.

Education was a decisive variable. In such households where the respondent had only an elementary education, 20.0% used high-risk disposal practices. On the other hand, 6.8% of university graduates reported similarly (χ2 = 11.23, df = 4, p = 0.024). The same trend also remained in the multivariate model. Controlling for employment status, income, age, and household status, primary graduates were over four times more likely to undergo high-risk disposal than university graduates (aOR = 4.12, 95% CI: 1.21–14.05, p = 0.023). This means that formal education can make one aware of the need to respect environmental issues and to use alternative, safer disposal options, even without favourable infrastructure.

The highest association was with employment status. The unemployed group had the highest rate of high-risk disposal (32.7%), significantly higher than that of government officials (8.3%) or NGO staff (6.7%) (χ2 = 28.47, df = 6, p < 0.001). Logistic regression was in concordance as well. The unemployed had nearly six-fold higher odds of having high-risk practices than government-employed individuals (aOR = 5.78, 95% CI: 1.82–18.34, p = 0.003). Even private-sector and self-employed workers were at higher risk (respective aORs of 3.21 and 4.05), further reinforcing the safety benefit of secure formal employment, perhaps through waste-collection premiums or greater anticipation of environmental compliance.

Household income was significant. The high-risk disposal rate was 21.9% in low-income households (≤GYD $85,000). Compared with the other groups, 7.6% of high-income households (>GYD $255,000) also practised similarly (χ2 = 15.23, df = 3, p = 0.002). Being low income was also a predictor in the adjusted model, where such homes were over three times more likely to be high-risk disposal (aOR = 3.37, 95% CI: 1.15–9.89, p = 0.027). This shows how economic poverty can prevent households from accessing regular waste management services and push them towards informal, mostly harmful options.

On the other hand, family status and age group did not independently correlate with high-risk disposal in either bivariate or multivariate analyses (all p > 0.05). Young adults (18–24 years) had a higher percentage (20.5%), though this difference was not significant after adjusting for other variables, compared with older adults (8.4% of 60+ years).

Overall, these findings attest to a dramatic socioeconomic divide in the management of plastic waste. It is founded under the intersection of low earnings, unemployment, and low education. It not only limits access to proper disposal but also poses greater environmental risks. Logistic regression indicates that the earlier-mentioned factors interact. It is necessary to put in place measures to address structural imbalances rather than individuals’ behaviours to protect human beings and water resources in Guyana.

3.7. Risk Assessment for Water Resources

This threat to community water sources is unevenly distributed, primarily affecting households facing multiple socioeconomic challenges. Our logistic model indicates that unemployment, low education, and low income are associated with improper waste disposal behaviours and independently predict high-risk dumping. This hazardous dumping correlates with visible environmental degradation and increasing water quality risks.

Households that dispose of their waste themselves, primarily due to unemployment (aOR = 5.78) and illiteracy (aOR = 4.12), have the most noticeable discarded waste nearby. About 46.6% report encountering “some” or “immense” rubbish in their vicinity. The presence of waste and vulnerable households facilitates the entry of plastic and other harmful substances into drainage systems and water bodies, especially during Guyana’s rainy season. Dumping is not random but results from inadequate coverage of official waste services, creating pollution hotspots in impoverished areas.

Waste burning, another hazardous practice, is also rising, with 40. 0% reporting significant waste buildup. Burning compressed waste releases toxins such as PAHs, dioxins, and heavy metals into the environment, which settle on land and water through atmospheric deposition or runoff. Logistic regression shows incineration is more common among private (aOR = 3.21) and self-employed individuals (aOR = 4.05), who often lack affordable disposal options despite being employed.

Conversely, low-risk disposal (using formal or informal schemes like municipal bins or scheduled pickups) is practised by those less likely to generate hazardous waste, with only 34.8% reporting significant rubbish nearby. Public sector workers, with the lowest likelihood of high-risk disposal, live in the least polluted areas, highlighting the link between institutional support, service access, and environmental health.

These patterns reveal an environmental justice issue: the socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are both more involved in risky waste practices and suffer the worst effects, creating a cycle that exacerbates plastic pollution and water contamination.

Although this study does not provide specific water-quality data, the strong link between predicted risk of hazardous disposal based on socioeconomic factors and observed waste buildup suggests pollution sources. In Guyana, where surface and groundwater are vital for households, agriculture, and ecosystems, this intersection of poverty, exclusion, and pollution threatens water security. Addressing these issues requires tackling the root causes of inequality that foster both environmental hazards and waste mismanagement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Socioeconomic Determinants of Waste Mismanagement: A Lens of Sustainability Equity

In line with our hypotheses, our evidence confirms that plastic waste mismanagement at the household level in Guyana is not due to individual laziness but rather a structural factor of socioeconomic marginalisation. Our binary logistic model shows that unemployment, lack of education, and low income are independent, statistically significant predictors of high-risk disposal practices, including dumping, incineration, and improper disposal of plastic waste. Unemployed households are nearly six times more likely to engage in such practices than those with government employment (aOR = 5.78), and those with only primary education face more than four times the risk (aOR = 4.12). These findings align with international evidence that environmental risks are unequally distributed along axes of economic and social power [

9,

10,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18].

From a sustainability perspective, the trend represents a complete failure of distributive and procedural justice. Families excluded from formal waste services due to costs, location, or employment status are forced to resort to environmentally harmful coping strategies. This contradicts the core principle of “leaving no one behind” embedded in the UN 2030 Agenda. Specifically, the findings criticise SDG 10 (Fewer Inequalities) and SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). By lacking equal access to waste facilities, vulnerable groups are burdened with additional labour in both causing and suffering from pollution, creating a cycle of social and environmental exposure.

Notably, family role and age were not significantly linked to disposal behaviour, indicating that campaigns targeting demographic groups (such as youth campaigns) will be less effective than those focusing on structural factors, such as income insecurity or exclusion from services. This further emphasises the need to move beyond awareness-raising as a policy objective in this case, towards providing material support and fostering institutional inclusion.

4.2. Water Resource Risk: From Behavioural Patterns to Environmental Justice

It is critical to emphasise that the link between disposal behaviour and water contamination is inferred from the visibility of dumped waste, a proxy indicator, and not from physicochemical or biological water quality measurements. While plausible, this association requires empirical validation through environmental sampling before causal claims can be substantiated.

The prevalence of visible rubbish is high across the board: 49.0% of homes use formal and informal collection, and 48.7% of self-disposers report dumped waste in their immediate surroundings. This widespread clustering of waste highlights the formation of pollution hotspots, where poverty, poor infrastructure, and systemic service failures come together to increase contamination risks to nearby water bodies.

Although there is no immediate data on water quality, a strong correlation between visible waste dumping, a sign of unsafe disposal, can serve as a valid proxy for contamination risk. Leachates, plastics, and combustion residues (e.g., PAHs, dioxins) can easily be transported in rain runoff to Guyana’s low-lying riverine and coastal villages [

21,

22,

23]. Waste incineration, a practice reported by 11.2% of households, adds to the risk through airborne deposition of non-transient organic contaminants, which subsequently enter aquatic environments [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

This double exposure, lower-income communities both cause and endure pollution, is an environmental injustice. It undermines the principle that less guilty groups, which contribute less to environmental degradation (such as lower-consumption, lower-income groups), should not have to bear the burden. In a circular economy, this waste also constitutes system loss: valuable materials are not recovered, but instead become carriers of harm, undermining SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

4.3. Formal and Informal Systems’ Role in Sustainable Waste Management

Our evidence indicates that having access to municipal or private formal waste collection services is strongly linked to cleaner neighbourhoods and fewer environmental hazards. Nonetheless, access varies depending on socioeconomic status, with government workers and wealthier families more likely to benefit. This reveals a key paradox in sustainability efforts: technical fixes alone cannot prevent social exclusion.

Municipal collectors, utilised by 21.6% of the population, serve a crucial bridging role in peri-urban settlements such as De Endragt and Good Hope. While their work helps keep open dumping under control, there is no simple solution. Incorporating informal collectors into formal systems is crucial since they can relocate without eliminating environmental risks, especially if collected waste is dumped or burned elsewhere afterwards.

A genuinely sustainable waste management system in Guyana would thus institutionalise and empower such non-formal stakeholders by providing them with training, machinery, and market access, facilitating decentralised, community-level resource recovery models of the circular economy [

3,

19]. This would, on the one hand, reduce pollution and, on the other, generate green employment, thereby fostering SDG 8 (Decent Work) and environmental objectives.

4.4. Policy Implications: Towards Equitable and Evidence-Informed Interventions

The current waste policy in Guyana focuses on mass education and infrastructure development. While these efforts are essential, our analysis indicates they are insufficient without safeguards that promote equity. For example, education campaigns can inadvertently harm those unable to pay collection fees or those living outside service areas.

We offer three policy directions along sustainability lines:

Implement Equitable Access to Waste Collection: Given the strong correlation between low income (≤GYD $85,000) and high-risk disposal, direct financial barriers must be removed. The government should pilot a subsidised or free collection service for households with incomes below a specified threshold, verified through existing social welfare registries. Funding could be sourced from an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) scheme levied on plastic packaging imports, creating a polluter-pays model that is both progressive and fiscally sustainable, aligning with the goals of the Low Carbon Development Strategy 2030.

Formalise the Informal Recycling Sector: The study notes that 8.9% of households use community organisations (often informal collectors). To harness this existing capacity and reduce the environmental burden of ‘middle zone’ dumping, these informal waste pickers should be integrated into municipal solid waste management plans. This could involve providing them with official identification, safety equipment, and access to waste transfer stations. Creating cooperatives could empower them to negotiate better prices for recyclables, turning a current problem into a source of green employment and improved material recovery rates.

Develop Context-Specific Environmental Education: Since education level was a key determinant (with primary graduates at 4× the risk of university graduates), awareness campaigns must be tailored. Instead of generic messages, community-led workshops should be co-designed to focus on practical local risks, such as how dumped waste blocks drains and exacerbates flooding during the rainy season. These initiatives should be integrated into adult literacy and school curricula in the target communities, framing proper waste disposal as a collective action for community health and resilience, rather than a matter of individual blame.

Importantly, interventions must be co-produced with local communities to avoid top-down impositions that overlook local context. Communities monitoring water quality and waste behaviours can build trust and produce relevant data.

5. Conclusions

The study shows that socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of how families in Guyana dispose of plastic waste and also directly affects water quality. Less educated, unemployed, and lower-income families are much more likely to use risky disposal methods, such as dumping, burning, and littering. These practices are closely linked to increased visible waste in residential areas, which increases the likelihood of plastic entering regional waterways.

The evidence underscores the importance of addressing socioeconomic disparities in learning and access to waste disposal as part of broader sustainable water resource management strategies. Merely increasing waste collection capacity or raising public awareness may be ineffective if socioeconomic barriers to proper waste management are not tackled. While tailored interventions show much promise, their credibility as protectors of water resources cannot be confirmed without on-the-ground environmental monitoring and participatory policy-making. A basis for diagnosis has been established in this research; the subsequent intervention requires research to test replicable models for waste management alone and to assess their contribution to water quality.

Future studies should focus on longitudinal research to assess the impact of individual interventions and intensive environmental monitoring. This approach aims to measure the real effects of household waste management on water quality. Additionally, research on the incentives and disincentives faced by household consumers who use informal collectors may offer insights into how to integrate these influential players into formal waste management systems.

6. Limitations

Moreover, although the study highlights policy-relevant correlations, the lack of longitudinal or experimental data undermines the robustness of the causal claims needed for large-scale policy development. The study’s geographical scope also limits the applicability of recommendations to Guyana’s broader national context.

Several limitations to this research should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the survey data limits causal inference regarding the relationship between socioeconomic variables and waste management strategies. A longitudinal analysis would be necessary to establish the direction of these correlations. The design did not control for cultural, psychological, or social-normative factors likely to confound or mediate socioeconomic associations. Its absence is a significant limitation, as interventions in changing behaviour will often require an understanding not only of ‘capacity’ but also of ‘willingness’ and ‘social permission’.

Second, the research relies on self-report data, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias. Household members might underreport negative environmental actions or overreport positive ones. Neighbourhood waste visibility as a proxy for water resource influence is also an indirect measure, and it cannot fully capture the complexity of plastic pollution pathways.

Third, this research focuses on only four specific communities in Guyana, which may reduce the generalisability of the results to other contexts or regions. Different communities may have diverse socioeconomic profiles or waste-disposal issues that could influence the patterns described in this study.

Finally, this research does not directly measure plastic pollution or water quality levels; instead, it uses environmental risk as a proxy. Future studies on environmental monitoring would provide more substantial evidence for the relationship identified in this research.

To proceed beyond the limitations of this study, three essential steps are recommended for subsequent research:

Take direct water quality measurements: companion studies need to collect water samples from drainage systems, rivers, and groundwater sources near high-risk disposal areas to quantify microplastic loads, leachate chemicals (e.g., phthalates, BPA), and biological indicators of contamination.

Conduct a Systematic Literature Review: A thoroughly conducted review of the socioeconomic determinants of waste behaviour in SIDS and tropical developing nations would have a stronger comparative framework and reveal research gaps specific to Guyana.

Establish a New Conceptual Framework: Building on these research findings, scholars should collaborate with stakeholders to develop a ‘Socio-Hydro-Environmental Behaviour Framework’ that incorporates socioeconomic status, cultural norms, hydrological vulnerability, and institutional capacity to predict and prevent plastic pollution from the outset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; methodology, S.H.; validation, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; resources, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; data curation, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; visualisation, S.H.; supervision, S.H. and T.D.T.O.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. and T.D.T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this study was carried out as part of the Prevention of Marine Litter in the Caribbean Sea (PROMAR) Project (Project Code: UNEP/PCA/Ecosystems Division/2024/7451). This project is being implemented by the University of Guyana – Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences (UG-FEES), with sponsorship and support from Germany’s Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUKN; German: Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Klimaschutz, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit). The project is administered by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Adelphi, the Cartagena Convention Secretariat (CCS), and the Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to this research complies with the ethical standards of the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Guyana and the University of Guyana’s Programme of Action.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article. The raw dataset used for analysis is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions regarding household-level information.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools, specifically ChatGPT (GPT-5.1 model), during the preparation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was utilised for assistance with data analysis and interpretation. The authors take full responsibility for the content and conclusions presented in this work, and all contributions from AI tools were carefully reviewed and validated by the research team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eneji, C.-V.O.; Onnoghen, U.N.; Edung, A.E.; Effiong, G.O. Environmental Education and Waste Management Behavior Among Undergraduate Students of the University of Calabar, Nigeria. J. Educ. Pract. 2019, 10, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Yukalang, N.; Clarke, B.; Ross, K. Barriers to Effective Municipal Solid Waste Management in a Rapidly Urbanizing Area in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitole, F.A.; Ojo, T.O.; Emenike, C.U.; Khumalo, N.Z.; Elhindi, K.M.; Kassem, H.S. The Impact of Poor Waste Management on Public Health Initiatives in Shanty Towns in Tanzania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN Plastic Pollution. Available online: https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/plastic-pollution (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ahmad, Z.; Esposito, P.; Ali, M. The Risk Factors and Problems of Waste Management in Developing Countries as Hurdles. Qlantic J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Verma, A.; Rajamani, P. Impact of Landfill Leachate on Ground Water Quality: A Review. In A Review of Landfill Leachate: Characterization Leachate Environment Impacts and Sustainable Treatment Methods; Anouzla, A., Souabi, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 93–107. ISBN 978-3-031-55513-8. [Google Scholar]

- Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission (GLSC). Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission Guyana National Land Use Plan; Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission (GLSC): Georgetown, Guyana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GoG Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. PUTTING WASTE IN ITS PLACE: A National Solid Waste Management Strategy for the Cooperative Republic of Guyana 2013–2024; Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development: Georgetown, Guyana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kalonde, P.K.; Austin, A.C.; Mandevu, T.; Banda, P.J.; Banda, A.; Stanton, M.C.; Zhou, M. Determinants of Household Waste Disposal Practices and Implications for Practical Community Interventions: Lessons from Lilongwe. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2023, 3, 011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saseanu, A.S.; Gogonea, R.-M.; Ghita, S.I.; Zaharia, R.Ş. The Impact of Education and Residential Environment on Long-Term Waste Management Behavior in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidou, A.; Ioannou, K.; Tsantopoulos, G.; Arabatzis, G. Citizens’ Attitudes and Practices Towards Waste Reduction, Separation, and Recycling: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondori, A.; Bagheri, A.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A. Pesticide Waste Disposal among Farmers of Moghan Region of Iran: Current Trends and Determinants of Behavior. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 191, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquart, P.-O.; Froehlich, Y.; Boyer, S. Plastic Pollution and Infectious Diseases. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e842–e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphela, T.; Manqele, N.; Erasmus, M. The Impact of Improper Waste Disposal on Human Health and the Environment: A Case of Umgungundlovu District in KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1386047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Age and Environmental Sustainability: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, É.; Palma-Oliveira, J.M.; Carvalho, A. From Intentions to Action: Enhancing Organic Waste Separation in Households in Portugal through Psychosocial and Operational Factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 521, 146318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Lu, W. Applicability of the Environmental Kuznets Curve to Construction Waste Management: A Panel Analysis of 27 European Economies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolano, S.; Lucio Gaeta, G.L.; Ghinoi, S.; Silvestri, F. Kuznets Justice in Municipal Solid Waste Production: An Empirical Analysis Based on Municipal-Level Panel Data from the Lombardy Region (Italy). Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.A. Illegal Dumping as an Indicator for Community Social Disorganization and Crime. Master’s Thesis, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hohl, B.C.; Kondo, M.C.; Rupp, L.A.; Sadler, R.C.; Gong, C.H.; Le, K.; Hertlein, M.; Kelly, C.; Zimmerman, M.A. Community Identified Characteristics Related to Illegal Dumping; a Mixed Methods Study to Inform Prevention. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 118930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.; Tian, D.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y. The Online in Situ Detection of Plastic and Its Combustion Smoke via Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Lett. 2023, 56, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L.; Ahmed, A.; Vukovich, J.M.; Rao, V. Hazardous Air Pollutant Emissions Estimates from Wildfires in the Wildland Urban Interface. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshtasbi, H.; Hashemzadeh, N.; Fathi, M.; Movafeghi, A.; Barar, J.; Omidi, Y. Mitigating Oxidative Stress Toxicities of Environmental Pollutants by Antioxidant Nanoformulations. Nano TransMed 2025, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAfee, E.A.; Löhr, A.J. Multi-Scalar Interactions between Mismanaged Plastic Waste and Urban Flooding in an Era of Climate Change and Rapid Urbanization. WIREs Water 2024, 11, e1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Vinoda, K.S.; Papireddy, M.; Gowda, A.N.S. Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste—A Review. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, O.W.; Ahmed, V.; Alzaatreh, A.; Anane, C. The Impact of Socio-Economic Factors on Recycling Behavior and Waste Generation: Insights from a Diverse University Population in the UAE. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Babu, K.; Deshpande, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Babu, K. Assessing the Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Household Waste Generation and Recycling Behavior in Chennai: A Survey-Based Study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Is Unemployment Good for the Environment? Resour. Energy Econ. 2016, 45, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejas Moncaleano, D.C.; Pande, S.; Haeffner, M.; Rodríguez Sánchez, J.P.; Rietveld, L. Inefficiencies in Water Supply and Perceptions of Water Use in Peri-Urban and Rural Water Supply Systems: Case Study in Cali and Restrepo, Colombia. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1389648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |