2. Which Economy? The Company, the Expert, or Materialism?

“We need to act quickly, drastically and in a coordinated way to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, but the economy is standing in the way.”

—Anonymous

This anonymous citation reports a commonly held view of the dilemma in which our current societies seem to be caught, particularly in market-based economies. In fact, most economists will agree with the beginning of the citation, whether regarding the objective of reducing emissions (which is crucial), or the verb (to act), or the complements used (quickly, drastically, and in a coordinated way). These are undeniable truths [

3].

However, most economists will be less convinced by the end of the statement: “but the economy is standing in the way”. This conclusion is imprecise, conveys preconceived ideas about economics, and clouds the debate on the measures to be adopted in the face of climate change. We propose below a clarification based on three different conceptions of “the economy”.

Economy as business activity. Firms create value added and jobs, but they also pollute. The short-sighted pursuit of profitability by business actors may thus appear as one of the major obstacles toward a sustainable future. However, in reality, business circles are very diverse and evolving. Some of them are genuinely convinced of the urgency to transform business practice. Moreover, firms do not operate in a vacuum: they depend on demand, technology, and regulations. Under appropriate regulations, the pursuit of profitability itself can provide strong incentives for change. Firms can reduce costs, improve efficiency, and strengthen long-term competitiveness by adopting cleaner practices. For example, empirical evidence [

4] shows that Chinese firms investing in green technologies benefit from enhanced long-term profitability, particularly through improved environmental performance. This illustrates how profit motives and sustainability goals can work hand in hand.

Economy as economic science. A second interpretation of what is meant by “the economy is standing in the way” is the discipline of economics (as a social science) rather than its practice (business). It is true that economists tend to be quite sympathetic to free markets, for reasons we discuss below. However, when it comes to climate change policy, it is the reverse (e.g., [

5]). For over twenty years, it has not been laissez-faire that has been recommended by most economic experts, but rather massive state intervention, on the basis of economic reasoning, to put a price on carbon. The aim of this paper is to explain why.

Economy as individual behavioral motivations. A third and more philosophical interpretation of this mistrust of “the economy” is that it is neither a criticism of business nor of the profession as such, but rather of the individual materialistic impulses that characterize the human species. This criticism may arise because of humans’ tendencies to favor short-term private gains over long-term social benefits. In fact, this is quite debated by economists themselves, and the empirical evidence suggests that people in general are not driven by selfishness alone (e.g., [

6]). However, it is also true that humans have frequently caused dramatic harm to the natural environment over the long run (e.g., [

7,

8,

9]).

In sum, although none is totally convincing, each interpretation of the final part of the statement conveys some truth but also deserves nuances. That said, unless one suffers from a particularly acute form of climate skepticism, the continuation of “business as usual” is clearly no longer an option. The question is which alternative to choose, and how to manage the transition. Faced with these enormous challenges, the following sections illustrate how, sometimes against the odds, the economists’ perspective may be a good one to take (The focus here is on climate change. For a more general presentation of the main sources of misunderstanding between economists and naturalists, see the brilliant summary by the authors of [

10]. Economics can also bring powerful insights in seemingly unrelated domains (e.g., emotions [

11] or religion [

12])).

3. Market Forces or Market Failures?

An illustrative example. Although most countries welcome private firms, whether to allow them to set their prices freely or to regulate their pricing is a delicate topic that depends on the context. For example, consider the case of the price of surgical face masks during the early months of 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruption of global supply chains, an enormous shortage of masks suddenly appeared in almost every country. What should governments have done? Let the price of masks go up or introduce price controls?

A pure free-market logic would have been to let the price increase to boost national production and solve the shortage in the long run. But apart from being terribly unfair for the poor, this classical price-rationing mechanism would have been too slow. According to the OECD [

13], by May 2020, world demand was over 10 times larger than global industrial capacity. It became urgent for governments to do whatever they could to redirect existing supplies toward the most pressing needs (hospitals) and guarantee minimal access for the rest of the population.

State-controlled rationing of surgical masks, trade restrictions, and industrial stimulus were thus introduced almost everywhere (e.g., [

14]). Even in market-friendly countries like the US, and even if it took some time, there was ultimately massive public intervention to contain price increases, stimulate domestic production, and be better prepared for future outbreaks [

15]. Other countries moved more quickly, particularly those with prior experience of coronavirus infections, such as Taiwan [

16] and South Korea [

17].

However, what is most revealing in the COVID-19 crisis is how quickly governments reverted to business-as-usual practices as soon as it became clear that the pandemic was over. Of course, they were pressed by business lobbies. But they were also much constrained by their limited resources. Using administrative procedures to substitute for price signals on every market in the economy would be a daunting task. This is why, in normal times, governments tend to specialize in a limited set of interventions while letting market forces drive production and consumption decisions on more mundane issues. Such reliance on market mechanisms is not blind but based on substantive economic analysis and evidence. It deserves complementary explanations.

Market forces. It is generally recognized that, since the Industrial Revolution, economic development has been most pronounced in societies that have offered the best guarantees of individual economic freedoms, including private property [

18]. How can we explain this paradox of “the prosperity of vice”, to use the title of Cohen’s excellent introductory book [

19], that individual selfishness led to economic progress? The basic intuition is that under certain conditions, prices help people and firms to make the most appropriate decisions from a social point of view. In economic theory, this intuition is formalized by the perfect competition model (Models in economics are simplifications of reality, stressing key dimensions under transparent and refutable assumptions. Models help to structure thoughts, describe mechanisms, and make testable predictions. The scale, scope, and time horizons of models are extremely diverse, as are the statistical techniques used to check their empirical relevance. Behavioral models in economics have received particular attention recently as they offer the possibility to address causal inference through experiments with practical implications in many different areas (e.g.,

https://thebehaviouralist.com/case-studies (accessed on 10 December 2025))).

Let us consider an ideal world in which invisible, incorruptible, and cost-free administrators guarantee respect for private property and contracts. The framework conditions are stable and transparent, and the economy is not facing any urgent crises or emergencies. Households and companies are profit-maximizing units independent of each other, and too small to influence the prices of goods, services, and factors of production. There is no pollution, no noise, no lack of information, and no external effects whatsoever (By “no external effects” we mean that all costs related to a market transaction on a given good are fully and exclusively borne by the producers, and all profits are fully and exclusively earned by the consumers).

Under these conditions of perfect competition, it can be shown that the law of supply and demand operating simultaneously across all markets leads to the social optimum (A condensed mathematical proof is available to the interested reader on

https://www.sustecon.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/appendix.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025). For a more extensive presentation of these notions, see chapter 1 of [

20]). In other words, letting people and firms use the price as a decision anchor leads to the best possible set of decisions concerning: (1) sharing the production effort between firms, such that the most efficient ones produce more (cost minimization), (2) allocating consumption between households according to their willingness to pay (benefit maximization), and (3) optimizing the quantity produced and consumed of each good (optimal choice of production-consumption mix). Adam Smith had this brilliant insight in mind when he articulated the famous “invisible hand” parable in 1776.

If, more than two centuries later, we continue to refer to the invisible hand, it is because this result is far from obvious. It also has two merits. The first is to provide an explanation for the paradox of the prosperity of vice, by highlighting the crucial role played by prices as a coordination mechanism between different decision-making units (see the insightful introductory chapter of [

21], which explains that nobody is specifically in charge of the daily supply of bread (or any other commodity) to the population of London in a normal day, even though this is in fact “astonishingly hard to believe”). The second is to explain the conditions under which the parable is valid, i.e., the assumptions of perfect competition, which ensure the coincidence of individual and collective rationality. These conditions are highly restrictive and therefore rarely fulfilled. This brings us to the realm of market failures.

Market failures. In a nutshell, there are as many market failures as there are possibilities of not satisfying the assumptions of perfect competition. For example, third parties not directly involved in a transaction can still be affected by its consequences. A typical case, which is called a negative externality, is residents living near a polluting firm who suffer from its emis-sions (In other cases, the externality may be positive, e.g., the individual use of a surgical face mask during a pandemic). Other imperfections may arise (the list is non-exhaustive) from incomplete contracts, lack of information, or from the strategic interaction between large players, which can influence the price.

These market failures become particularly important in the context of climate change. The following two examples help illustrate this point. The burning of fossil fuels is the major source of greenhouse gas emissions and thus contributes to the social cost of climate change. However, in the absence of state intervention, this external cost is not considered by private agents and generates additional costs not only for society as a whole but also for future generations. Likewise, property rights over natural resources like tropical forests are difficult to define and enforce. In the absence of a collective arrangement, the pursuit of individual self-interest leads to overexploitation of these natural resources, or even to their outright disappearance. This brings us to another parable, that of the “tragedy of the commons”, introduced by William Forster Lloyd (an economist) in 1833 and revived by Garrett Hardin (an ecologist) in 1968.

A complication that makes market failures difficult to generalize is that there is no single remedy for them. Even for a specific market failure (e.g., a polluting activity), various solutions exist, including bans, taxes, or standards to be respected. For example, the multiplicity of solutions found to protect resources affected by the tragedy of the commons earned Elinor Ostrom the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009. Depending on the magnitude of the market failure and on the state’s capacity to respond, the optimal policy may lie anywhere along a spectrum of interventions: from private negotiation on the one end to full takeover by a public authority on the other end, with intermediate cases such as incentives or technical standards.

Also, note that what is considered optimal depends on the normative criterion that is selected. For the sake of conciseness, and unless stated otherwise, we will adopt below the perspective of a benevolent social planner, i.e., a hypothetical decision-maker aiming to maximize social welfare by weighing social costs against social benefits across all agents. However, much should also be said about the distribution of these costs and benefits across firms, people, and generations. In other words, even if we focus on social efficiency here (in the sense of maximizing the size of the social cake), equity considerations (how the cake is shared among agents) also matter a lot in the real world.

A complete treatment of market failures would be out of scope for the present paper. However, one may use the broad structure of public expenditure to get a first approximation of which areas appear to matter most in practice. Whatever the country, an important share will be devoted to health, education, security, and the environment. This is not to say that outside these categories, all markets function perfectly well. However, under normal circumstances, markets for bread, shirts, or teapots can be considered sufficiently competitive to let prices fluctuate with changes in fundamentals (e.g., consumer preferences or production technology). As illustrated earlier by the case of surgical masks, this allows governments to mobilize their limited resources into areas where public intervention is most needed. Protecting the environment is one such area, and in the case of climate change, it comes with huge challenges, as discussed below.

4. What Is Climate Change from an Economic Perspective?

Unfortunately, climate change brings together just about every conceivable market failure from an economic point of view. The external costs generated by CO2 emissions from a multitude of production and consumption actions are clearly not reflected in the prices of inputs (fossil fuels) or goods and services consumed (air travel). The spatial scale (the globe), the temporal scale (centuries or even millennia), and the number of stakeholders (all of us) mean that private negotiations cannot be expected to deal with these external effects. State intervention is required, but it is hard to find a political consensus between those in favor of vigorous actions and the powerful lobbies that oppose them (mainly from the energy, construction, and transport sectors, the major polluters). A core argument is that unilateral action will benefit the rest of the world while deteriorating the competitiveness of domestic firms. This is correct and makes climate change a clear international coordination issue. Unfortunately, at the international level, there is no dedicated organization with strong enforcement powers. This leaves us with international treaties (Kyoto, Paris), but their negotiations have proven very difficult, with mixed results, to say the least.

To illustrate the difficulty of international coordination on climate change, let us consider a stylized textbook case of strategic interaction between two countries, say China and the USA. The two countries are identical in every respect, and there is a single lever for action, either to contribute (C) or not to contribute (NC) to the reduction of CO2 emissions. The benefit of the contribution is public, i.e., accrues to both players, each country gaining 2, but the cost is private, equal to 3. Collectively, it would be in the interest of both countries to agree so that each contributes and earns 1 (a benefit of 2 + 2 minus a cost of 3). But this situation is not stable, given that each country has an individual interest in “cheating”, i.e., letting the other contribute, without contributing itself, and hoping to end up with a free-riding benefit of 2. Ultimately, the only stable equilibrium is one where neither country contributes, which is the worst outcome at the collective level.

In game theory, this type of situation is called a Prisoner’s Dilemma. It is a configuration of incentives such that the lack of coordination between two profit-maximizing agents leads to the worst outcome from a collective point of view (a negative sum game). In this sense, it is the exact opposite of the invisible hand parable and illustrates a major source of market failure. Similarly to the perfect competition framework, it is based on assumptions that can be altered, leading to a variety of alternative outcomes (To consider just one extension, assume that in the China–USA case, the estimated cost of inaction increases. Now, each country suffers a cost of 2 if none contributes. In this case, no contribution at all by both countries is not an equilibrium anymore. One of the two countries will eventually play “chicken”, i.e., contribute to minimize the costs, while the other country will win free-riding benefits. Further insights and more formal treatment can be found in [

22] for international environmental treaties or [

23] for global collective action in general). For example, countries differ in their vulnerability to climate damages and in their abatement costs, which can break the symmetry of payoffs and shift strategic incentives. Still, the Prisoner’s Dilemma remains a useful illustration of cheating incentives and the free-riding problem, as reflected in the actions of the US administration under President Trump’s two terms (i.e., the withdrawal of the USA from the Paris Agreement and the manipulations of the social cost of carbon, as discussed in

Section 7 below).

It would be wrong to conclude that all environmental treaties are doomed to failure. Some famous counterexamples exist, such as the Montreal Protocol (1987), which was negotiated in record time and led to a drastic reduction in chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) emissions worldwide in less than ten years, effectively preserving the stratospheric ozone layer that protects the biosphere from UV radiation. As argued in [

24], this counter-example is edifying in many ways, as it shows how much more complex the situation is in the case of CO

2. The damage caused by CFCs (cancer) was immediate (and not to future generations) and directly affected the main emitters (therefore, a national issue). The situation is opposite for climate change, with strong intergenerational and international dimensions. In the case of CFCs, the cost–benefit analysis was clearly favorable, even for unilateral national measures, which meant that national consensus was easy to achieve and there was no global Prisoner’s Dilemma. Emission sources were limited to a few countries and a few sectors (mainly refrigeration and aerosols), and substitution technology was known and cost-effective. In the case of CO

2, emission sources are multiple, linked to the ubiquity of fossil fuel combustion, and the transition to sustainable energy substitutes is characterized by high levels of uncertainty. Finally, the USA played a leading role in the negotiation of the Montreal Protocol, whereas its leadership has been much more inconsistent in the case of climate policy (see

Section 7).

5. Why Carbon Pricing? Carbon Taxes and Cap-and-Trade Regimes in Theory

A thought experiment. Let us consider a different world where three conditions prevail. First, every single gram of carbon-equivalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere can be traced back to its human origin, i.e., a specific person. Second, the social cost is known with certainty, i.e., a metric that encapsulates in a single number all present and future suffering on Earth generated by this additional gram of carbon in the atmosphere. Third, there is a magic button that converts this social cost into an immediate and proportional pain for the responsible person.

Imagine now that you press the button. What happens? All controversies, past and present, regarding climate change instantaneously disappear. They are replaced by myriad individual decisions from agents who suddenly and fully realize all the consequences of their carbon emissions. Now they logically seek to reduce emissions through the best available alternative. The magic button assures that individual incentives yield the best outcome at the aggregate level, i.e., for society as a whole.

The three conditions of the thought experiment are unrealistic, but the basic message is important. Building a mechanism that would make each person generating new carbon emissions bear the full cost of all consequences has the potential to turn the tables. The very market forces that are at the origin of climate change could be tamed to powerfully contribute to mitigation. The good news is that in the real world, two mechanisms do exist to replace the magic button: carbon taxes and emission trading systems (ETSs, also referred to as cap-and-trade systems).

The carbon tax is a priori simple. It consists of estimating the carbon content of a given production or consumption and making the producer or consumer pay for it using an appropriate carbon price. As in our thought experiment, the tax generates incentives to curb carbon emissions at the individual level. One difficulty is to find the appropriate carbon price, i.e., the level of the tax. ETSs follow a different logic. They consist of attributing a limited number of emission allowances, or transferable emission permits (TEPs), to the emitters. Each emitter can then either buy or sell TEPs on a newly created carbon market. The equilibrium price of TEPs reflects the scarcity of allowed TEPs vis-à-vis the initial level of emissions. Allowances can be attributed for free or through auctions. In the latter case, ETSs also generate government revenues, like the carbon tax.

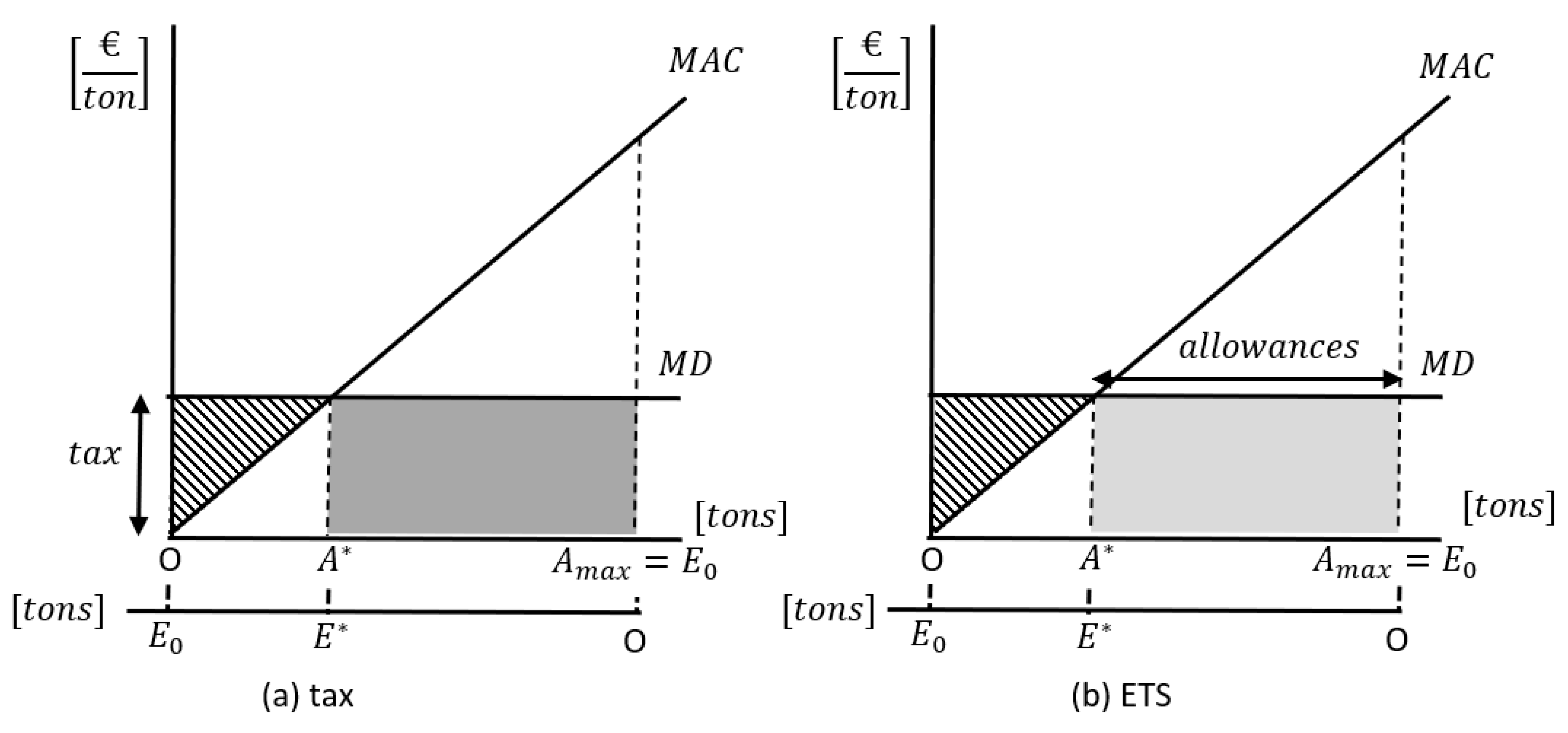

A simple efficiency diagram. Although different in their design, the tax and the ETS regime share the same desirable properties in terms of efficiency.

Figure 1 illustrates this point in a very stylized way for a representative agent. On the horizontal axis, we represent emission abatement,

, in tons, i.e., the amount of CO

2 emissions that are reduced. The effective amount of emissions which are released,

, is read from right to left and is assumed equal to

prior to government intervention (

). On the vertical axis, we represent the two relevant marginal values, in euros per ton (“Marginal” in economics means “per extra unit”. Consequently, the area beneath a marginal cost schedule represents total cost across all units). The marginal damage of emissions,

, is assumed constant, and the marginal abatement cost (i.e., the marginal cost of reduced emissions),

, is assumed to increase, reflecting larger opportunity costs as the abatement effort becomes larger.

For the benevolent social planner, neither complete laissez-faire (emissions ) nor total abatement () is recommendable. The optimal solution is , which generates a net social welfare given by the shaded area, i.e., the difference between avoided damages (read beneath the schedule) and total abatement costs (read beneath the schedule). This social optimum level can be achieved either by setting an optimal level of the tax equal to in the left-hand side panel (so that the marginal cost of the last abated unit is just equal to ) or an optimal level of emission permits equal to in the right-hand side panel (so that the agent is ready to sell one unit of allowances at a price just equal to ). Note that if allowances are perfectly auctioned, government revenue, i.e., the grey area, is identical in both cases.

Apart from social efficiency (a concept that is debated, as mentioned in the next section), taxes and ETS regimes are also equivalent in terms of cost efficiency. By cost efficiency, we mean that the total abatement effort (whether or not this total level is optimal for the benevolent planner) is shared optimally between agents so that total abatement cost is minimized. This is not immediately apparent in

Figure 1, as we assumed a single representative agent. However, an extension to

heterogeneous agents is straightforward. Imagine that an initial sub-optimal sharing rule is such that

. Then, maintaining the total abatement level constant, re-allocating the abatement effort toward agent

would reduce total costs, as the decrease in abatement cost for agent

would be larger than the increase in abatement cost for agent

. Thus, cost efficiency implies that

for all agents. This is exactly what is implied by the common tax or the common ETS price faced by all agents in the two considered policies.

6. Why Carbon Pricing? Carbon Taxes and Cap-and-Trade Regimes in Practice

Despite the above-mentioned theoretical advantages, several complications affect the design and implementation of real carbon pricing policies. To illustrate practical caveats, we list below the main points of discussion, followed by a brief presentation of two emblematic cases (Interested readers may consult [

25] for a public policy presentation or [

26] for an academic review).

Uncertainty regarding marginal damage.

Figure 1 assumes that

is constant and well known. In practice, it is not the case, as discussed in more detail in

Section 7. Disagreement on

does not mean that carbon pricing becomes irrelevant, as cost efficiency remains untouched. However, the level of the tax or the cap on allowances becomes contingent on targets set by another instance (e.g., climate scientists or international negotiators).

Uncertainty regarding marginal abatement costs. Changing circumstances may affect the position of the

schedule and thus the optimal level of abatement. For example, technical progress in renewables may decrease marginal abatement costs. Using

Figure 1 (constant

), one can check that under a tax regime, this will lead to an optimal increase in the abatement level, whereas under an ETS regime, there will be a sub-optimal drop in the price of TEPs. However, note that this is due to the debatable assumption of the

being constant.

Administrative complexity. In principle, the tax is simpler in administrative terms as it can be based on existing taxes, such as excise taxes on fossil fuels. ETS regimes are more sophisticated and often limited to the largest emitters, i.e., energy producers and industrial sectors. The simplicity of the tax also makes it more salient and exposed to the two criticisms that follow.

Impact on inequalities. As poor households spend a larger share of their income on energy than richer ones, carbon pricing tends to be regressive (see [

27] for a meta-analysis). Additional general equilibrium effects, such as those on employment and income, may exacerbate the problem (e.g., [

28]).

Impact on competitiveness. Fossil-fuel-intensive sectors are harder hit by carbon pricing and will tend to lobby to be less exposed through tax reliefs or free allowances (e.g., [

29] in the EU case or [

30] in the Swiss case). Moreover, if the product is traded and other jurisdictions apply a lower carbon price, domestic firms may lose competitiveness, and there is a risk of carbon leakage, i.e., a relocation of carbon-intensive production abroad. Border tax adjustments may be introduced to reduce carbon leakage, but their design, effectiveness, and compatibility with WTO law are not evident ([

31,

32,

33,

34]).

Use of government revenues. Carbon pricing generates new fiscal revenues (only if allowances are auctioned in the ETS case). This creates tensions but also opportunities for governments to use these additional funds to reduce fiscality in other domains, soften the impact on inequalities or competitiveness, or invest in environmental projects (The latter category is on the rise and represents more than 50% of carbon pricing revenue worldwide according to the World Bank [

35]). Proper use of revenues may increase political acceptance (e.g., [

36]).

Interaction with other policies. Other policy measures exist to achieve national targets. Technical requirements, green subsidies, or climate funds (e.g., [

37]) are also considered and discussed.

Given the above intricacies, it is not surprising that the coverage and stringency of carbon pricing vary a lot across countries and even across jurisdictions within a country (as in Canada, Mexico, or the USA). According to the World Bank (

https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 14 December 2025)), 28% of global emissions are covered today by carbon pricing (23% for ETS, 5% for the tax), with a very large price range (from 0.1 USD/tCO2e to more than 150). This heterogeneity provides an interesting ground for testing whether carbon pricing reduces emissions. Differences in samples or statistical techniques used to isolate the specific impact of carbon pricing policies explain why some authors find significant effects [

38], while others do not [

39]. Most reviews suggest significant impacts for both types of carbon pricing policies (e.g., [

40]), although the estimated effects vary substantially. Using a machine learning approach applied to more than 15,000 studies, the authors of [

41] find that carbon pricing is associated with emissions reduction of between 4% and 15%, after correcting for publication and study design biases.

The British Columbia (BC) carbon tax. This is one of the best-known examples of a carbon tax. It was introduced in 2008 as an ambitious scheme, covering more than 70% of provincial emissions, with only limited exemptions (e.g., agriculture). The initial price started at 10 CAD/t of CO2e (corresponding roughly to 2 cents per litre of gasoline) but was set to increase by CAD 5 every year thereafter. To cement political acceptance, the tax was conceived to be fully revenue-neutral, i.e., all the proceeds would be returned to households or firms through cuts in other taxes. During the last decade, although the annual increase was temporarily suspended in 2012–2017 (at 30 CAD/t) and during the COVID years (at 40 CAD/t), the BC tax experiment appeared to be thriving and deserving emulation (e.g., [

42]). Then, quite suddenly, it was dropped in April 2025. Explaining why this happened provides a perfect illustration of the limitations mentioned above.

To begin with, the experiment was not as smooth and clear-cut as it is sometimes claimed ([

43,

44]). The tax had been debated politically since the beginning, and its support was never unanimous. Its acceptance was linked to favorable circumstances. It was adopted during a period of high public concern for the environment and backed by a committed right-of-center government with good relationships with the business community. Once it was implemented, the carbon tax benefited from the incumbent effect, i.e., replacing it would have meant increasing taxes elsewhere at constant budgetary levels. It is true that over time, as the proceeds of the tax kept rising, part of them were recycled to finance decarbonization projects. This deviation from the revenue-neutral principle generated some tensions, but no general public outcry, as it also strengthened the inclusion of the tax within the broader spectrum of low-carbon policies, including the federal carbon tax scheme adopted in 2017. Moreover, academic studies were broadly supportive, suggesting that the tax was reducing emissions (between 5% and 15% according to [

45]) with no strong effects on the rest of the economy nor on income inequalities.

Circumstances became more adverse in the last two years before the abandonment of the tax. There was an outburst of inflation in the post-pandemic period (2021–2023), which pushed cost-of-living issues to the top of the political agenda. This came into direct conflict with the gradual increases of the carbon tax, which reached 80 CAD/t in April 2024 (worth more than 18 cents per litre of gasoline). Federal politics were also in flux. Tensions within the ruling Liberal party led to the resignation of the Prime Minister in early 2025. The threat of a tariff war and the annexation proposal by the incoming Trump administration heated the debate and gave the fight to preserve Canadian jobs and competitiveness a sense of national urgency. Carbon pricing became a polarizing issue in the election campaign. The opposition Conservative Party of Canada adopted the slogan “Axe the Tax”. The Liberal Party committed to removing the consumer-pay fuel charge of the carbon tax scheme during the campaign, while keeping the industrial carbon tax. In the end, the Liberal Party won the April 2025 election and completed its promise, leading the provincial authorities to follow suit. The short and hard lesson is that, due to equity concerns and the reversal of good fortunes, the consumer part of the tax was scrapped, the industrial part was preserved, and the credibility of the policy was weakened.

The EU ETS. The EU ETS is another major reference point on carbon pricing. Compared with the BC tax, apart from being based on quantities (emission cap) rather than prices (carbon tax), it took a lot more time in the making. The two differences are linked to the administration caveat mentioned above. It is a totally different story to create a new market (moreover, at the international level) rather than introducing a tax. We refer briefly to the major aims and main phases of the EU ETS regime before presenting a short review of its impact (see [

46] for a recent policy review and [

47] for a bibliometric review).

Figure 2 reports the evolution of the carbon price on the EU ETS market since its introduction in 2005. A quick look at the figure may give the impression of an experiment that initially failed until a correction was made in 2015. Fluctuations are strong, the price is mostly below 20 EUR/t or even 10 EUR/t during the first 10 years and then rises to the 70–90 EUR/t range for the rest of the period. This first impression is misleading. Indeed, corrections were introduced, but a lot more progressively and consistently than the immediate appreciation of the price pattern suggests.

Since the beginning of this complex project, the first phases were designed as rather experimental ones. Phase 1 (2005–2007) was essentially set to test the emission trading mechanism. Allowances were allocated to more than 12,000 power stations and industrial plants in 31 countries, covering roughly 40% of total emissions in the zone. To soften competitive concerns, more than 90% of allowances were allocated freely and based on historical emissions (this means that the price on the auctioned allowances, which appears in the figure during that phase, only concerns a limited number of firms). Moreover, it was biased downward due to early characteristics of the design, in particular, the fact that during that phase, allowances could not be banked, i.e., stored for use in subsequent phases.

The major aim of phase 2 (2008–2012) was to bring the EU ETS into line with the committed targets of the EU under the Kyoto Protocol. The share of auctioned allowances increased slightly, and banking of allowances was now allowed, which helped push up prices initially. This is because with banking, and since firms expect scarcity, they are willing to pay more to save allowances for later use. However, this upward pressure was largely overwhelmed by two strong downward forces. First, the contraction and slow recovery of economic activity after the 2008 financial crisis sharply reduced emissions, generating a surplus of allowances. Second, this surplus was further amplified by the development of renewable energy sources, favored by other climate policies in the EU.

The next two phases are longer and seek to consolidate the system. Phase 3 (2012–2020) introduced a linear reduction factor (LRF) on the EU-wide emissions cap of 1.74% per year. More allowances were auctioned, although free allowances remained for sectors particularly exposed to carbon leakage (e.g., the steel and fertiliser industries). The possibility of claiming international emission reductions (offsets) was subject to stricter standards. A buffer mechanism, the Market Stability Reserve (MSR), was introduced in 2015 to stabilize price fluctuations. Under the MSR, the number of auctioned allowances is automatically reduced (increased) when the total number of allowances in circulation reaches an upper (lower) limit. All these elements have been tightened in phase 4 (2021–2030), with an LRF rising to 2.2% in 2022 and 4.3% from 2024 onward, an additional reduction in the share of free allowances, international offsets excluded, and the MSR further strengthened. This should lead to a reduction of 62% in EU emissions in 2030 compared to 2005. An extension of the scheme to smaller companies, the ETS-2 project, is planned for the coming years.

Having stressed the logic behind EU ETS reforms, it is also important to acknowledge its limits (see also [

48] for an empirical analysis of the distributional effects of the EU ETS between and within countries). Apart from the seemingly erratic behavior of prices, it is not evident how to identify their real impact on emissions. This may look surprising given that the EU has the authority to fix the cap. However, as illustrated above, there are many factors influencing carbon emissions, which makes the identification of the causal effect of the EU ETS regime a complicated matter. Controlling for these effects, and based on a large sample of European firms, the careful analysis of the authors of [

49] suggests that the EU-ETS did manage to reduce emissions significantly over the 2005–2014 period, in a range between −7% and −16%. Moreover, the EU scheme did not appear to alter the performance of the regulated firms or the overall competitiveness of the industry.

Despite this positive micro-based evidence, there are sources of concern. The authors of [

50] suggest that the true impact on emissions may be smaller than expected due to a macroeconomic rebound effect, i.e., the unintended consequence of higher energy demand triggered by the reduction in energy intensity. According to [

51], the macroeconomic impacts of phase 4 have been underestimated. This analysis suggests that the tightening of regulations has contributed to the recent increase in consumer prices, a clear warning signal given the recent BC tax experience.

The MSR mechanism is also debated. A recent review [

52] is quite favorable, crediting the MSR for lifting the EU ETS carbon price out of a decade-long depression. However, the author of [

53] points to another unintended consequence, this time on the behavior of financial actors. With external investors being admitted to the EU ETS market, it is subject to speculation. Speculation is not necessarily destabilizing if it is based on fundamentals (i.e., factors determining the intrinsic value of allowances, such as the LRF or abatement costs). However, it becomes so if price expectations are based on sentiments, and the current setting of the MSR makes it vulnerable to these effects.

Speculators are also acknowledged in the energy-system model used by [

54], but their influence is estimated to be secondary vis-à-vis two other factors. Simulations suggest that the recent increase in the EU carbon price was due to both the regulatory tightening in phases 3 and 4 (as could be expected) and also to changes in the behavior of regulated companies regarding energy investment. More specifically, actors in the electricity and industry sectors became more farsighted following the improved credibility of the ETS scheme and climate targets. Thus, a virtuous cycle appeared between higher policy credibility, extended foresight, and higher carbon prices. However, the same elements could function in a reverse dynamic in the case of an economic or political crisis.

To sum up, as a policy instrument, carbon pricing is both praised and debated. On the one hand, it is recommended by experts and international organizations (e.g., [

3]) and credited by enthusiasts to have curbed European greenhouse gas emissions in recent years (e.g., [

55]). On the other hand, as mentioned above, its concrete application is full of caveats, and causality is hard to prove, even in the case of the EU ETS. However, even if it is not directly applied as a mandatory tax or an ETS regime, carbon pricing may still be very useful as an accounting yardstick, as we shall see below.

7. Why Carbon Pricing? An Accounting Yardstick

A key assumption of the thought experiment described at the beginning of

Section 5 is that it is possible to measure the cost of an additional unit of carbon released in the atmosphere. Given that effects span worldwide and across centuries, this may seem unfeasible. It is not. For decades, complex simulation models called Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) have allowed researchers to estimate the monetary value (in USD or local monetary units) of damages generated by the release of one additional ton of carbon equivalent into the atmosphere, in principle covering all damages worldwide and across all present and future generations. Note that it is not an infinite number, because future costs are reduced using a discount rate to account for expected future growth and time preference (e.g., [

56]). The choice of the appropriate discount rate itself is contested, as mentioned below.

IAMs are complex algorithms that include modules to simulate the evolution of the climate under alternative scenarios, to convert climate change into damages to human populations, and to convert those damages into costs. The pioneering contributions of William Nordhaus in this domain have earned him the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in economics. However, even if the methodology has greatly improved over time, it is fair to say that IAM estimates rest on many uncertainties regarding the severity of the damages, the inclusion of catastrophic risks, or the choice of the discount rate. This has generated controversies among experts (e.g., [

57,

58]) and also explains why IAMs typically generate a distribution of carbon prices around a central case.

An important distinction is warranted here. IAMs can be used to estimate the price of carbon under two different configurations: the social efficiency perspective or the cost-efficiency perspective. As discussed in the stylized case of

Figure 1, the social efficiency perspective is the most ambitious one in terms of how far economics can go. In line with neoclassical theory, it assumes that it is possible to aggregate social welfare across people and generations and find the optimal price trajectory to maximize it. This is referred to as the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC). A less ambitious stance is to drop the optimality claim and focus on cost efficiency alone. In this case, modelers consider the climate goal as given (e.g., by the Paris Agreement or Net Zero objective) and use IAMs to estimate the required carbon price trajectory necessary to achieve this exogenous goal. This might be referred to as the (Cost-)Efficient Price of Carbon (EPC, our wording).

Depending on modelling assumptions, the gap between SCC and EPC estimates can be large. For example, Nordhaus [

59] estimates an average SCC of 44 USD/t in 2025 against an average EPC of 284 USD/t to limit global mean temperature increase to 2.5 °C. However, the more recent survey by the authors of [

60] puts a central value of the SCC at USD 185 per ton of CO

2, well within the range of the recommended levels of the US Biden administration (between USD 120 and 340 per ton, see [

61]).

Exploiting these controversies, the two Trump administrations downplayed the role of SCC figures. In both cases, this started with disbanding the Interagency Working Group in charge of SCC estimates. In 2017, the administration pushed the methodology to its limits to generate a very low SCC. The central reference value dropped from USD 50 to less than USD 10 per ton (This was managed by selecting a very high discount rate of 7% instead of the usual 2–3% figures (the change may seem small, but over a long period of time, it does make a huge difference) and by referring to a “domestic” SCC, which rules out damages outside US territory (negating the global dimension of the collective action problem)). In 2025, it opted for an even more radical approach, instructing federal agencies to “not monetize” climate impacts at all, on the grounds that there was too much uncertainty involved. This is quite ironic, as most experts will concur that greater uncertainty calls for more stringent climate regulation, not less ([

62,

63]).

Whether under the SCC or the EPC perspective, carbon price values constitute an accounting yardstick, which is crucial for policy guidance. In the climate policy domain, they can be used to evaluate the cost of inaction (i.e., keeping on with business-as-usual trends), to identify the most cost-effective policy measures, and to select their optimal mix under a variety of scenarios. They are also useful for cost–benefit analysis of other policies that involve changes in greenhouse gas emissions, e.g., in the energy and transport sectors. This explains why, in contrast with the stance of the current US administration, they are increasingly used in a variety of countries.

8. Why Carbon Pricing? A Way to Look Ahead

Given the extent of the problem and the lack of commitment by the major players, it is tempting to give up any hope of serious measures being undertaken on a significant scale to mitigate climate change. However, even if economists are sometimes called “dismal scientists”, most of them would still agree that such a dire vision is misplaced for at least three reasons.

First, provided they are not taken to the letter, the three conditions of our thought experiment help to frame the problem and realize that solutions are not completely out of reach. We have seen that despite their uncertainty, integrated assessment models (IAMs) generate science-based estimates of either the social cost of carbon (SCC) or the efficient carbon price (ECP) required to achieve climate targets. Besides, even if it is not possible to attribute precisely the responsibility for every single gram of carbon released into the atmosphere, we have much more reliable data than before to attribute responsibilities. The widespread adoption of greenhouse gas inventory standards since the 1990s has greatly improved our perception of the problem and our understanding of the most appropriate ways to tackle it (which earned Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007). Finally, though they present practical difficulties, carbon taxes and emission trading systems have the considerable advantage of generating revenue and cost-efficient responses, which is why they are a recognized part of national and international climate agendas and policies.

Second, beyond the stop-and-go nature of US politics and the outrage of climate activists, recent trends at the global level, including in emerging economies, are toward more, not less, climate action. According to the latest World Bank report [

35], the share of global emissions directly covered by carbon pricing has risen from 12% to 28% in the last ten years, and their price has roughly doubled, even if it remains way below the central value of recent SCC/ECP estimates. Sadly, these efforts—which are challenged by the present US administration—are insufficient to reverse present trends in greenhouse gas emissions. But they are backed by other climate policy measures, such as green subsidies or technical standards. Moreover, even if the mapping between carbon prices and actual policies is contingent on many factors, provided we keep on measuring carbon prices, future increases will raise the stakes for urgent climate action and strengthen research of all types to cope with our complicated future.

Third, this is a complex and long-term game in which it is crucial to stick to fundamental economic principles, i.e., concepts that have been validated over time, even when they appear counterintuitive. Economists are well experienced in this regard. It took a century for most observers to admit that centrally planned economies, which looked sound on paper, often led to economic fiascos because they failed to nurture the positive aspects of market mechanisms. Likewise, it took fifty years after World War II to create the World Trade Organization and its non-discriminatory framework, even if the process has stalled and protectionism is now back with a vengeance. This does not mean that the underlying concepts were flawed, but rather that they have become progressively misaligned with national politics and proved unable to be applied at a global scale, at least in their present form.

Unfortunately for those calling for urgent action, global climate policy will likely face a similar fate, as illustrated by the disillusionment following the Paris Agreement. Yet, the lack of an ambitious and binding agreement at the global level should not be seen as proof of definitive failure. Rather, in line with the “polycentric view” of Elinor Ostrom (see [

64,

65]) or the “climate clubs” of William Nordhaus [

66], attention should focus on those limited initiatives that do exist. If these initiatives are based on solid evidence and incentives, such as carbon pricing, they will flourish and may develop into a substantive tool for mitigation.

To conclude, economists have no magic button to address climate change. However, there is an economic prism through which one can identify what may really matter in the long run. Our climate is under threat, while the resources to cope with it, including time, are limited. Moreover, we lack institutions and mechanisms to coordinate the response. Economists have been studying such scarcity-induced coordination issues for a long time. They know that prices and market mechanisms may both help, through the efficiency-seeking signals they send, and hurt, when the price signals are distorted by market failures. This is why, despite its limitations, carbon pricing is considered by most economists (e.g., [

67]) to be a crucial part of the climate policy agenda.