From Passive Consumers to Active Citizens: A Survey-Based Study of Prosumerism in Jerusalem

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cities and Energy Transition

1.2. Social Innovation, Energy Citizenship, and Prosumers

1.3. Research Gap

2. Case Study: Jerusalem

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Sampling

3.2. Survey Design

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

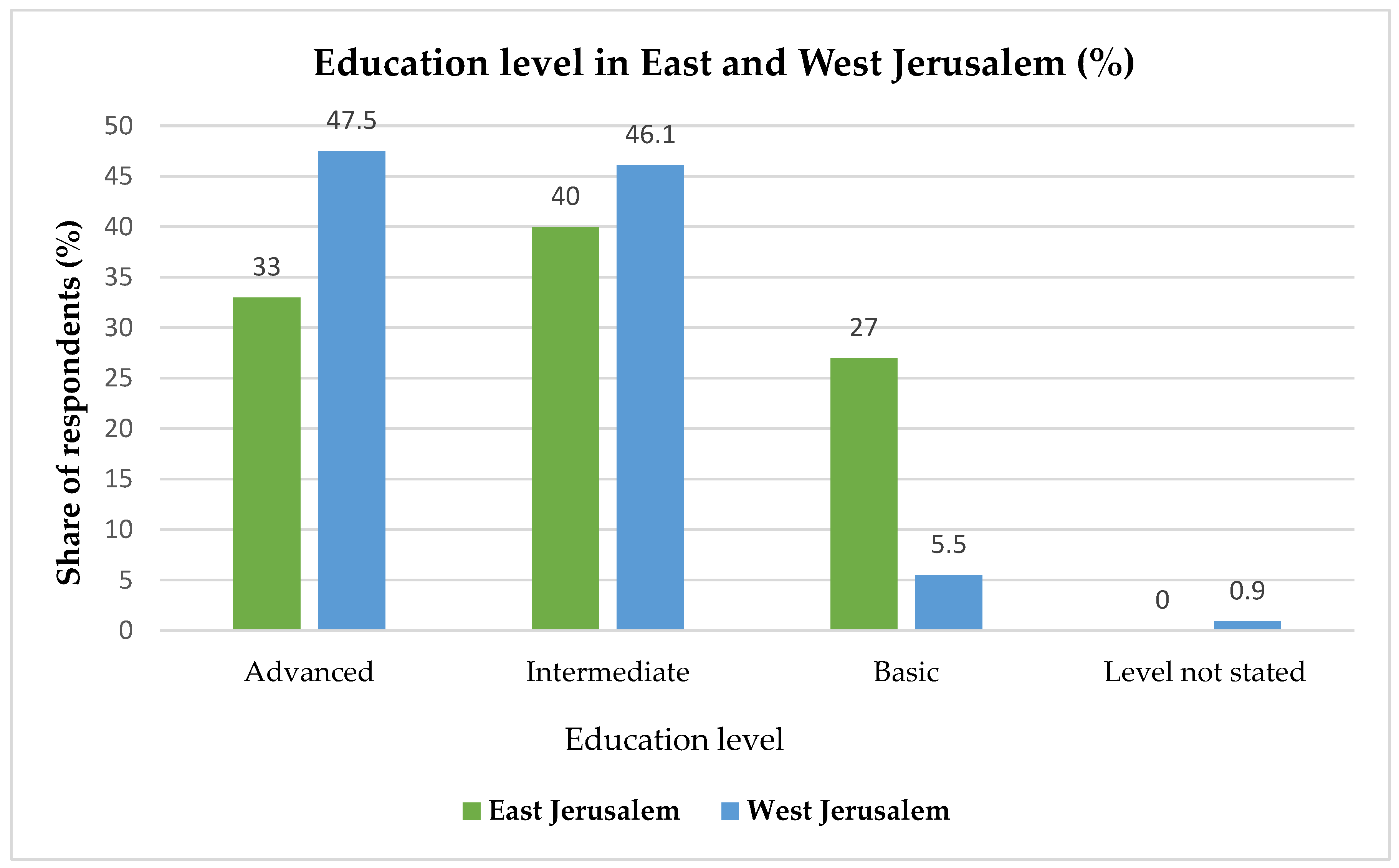

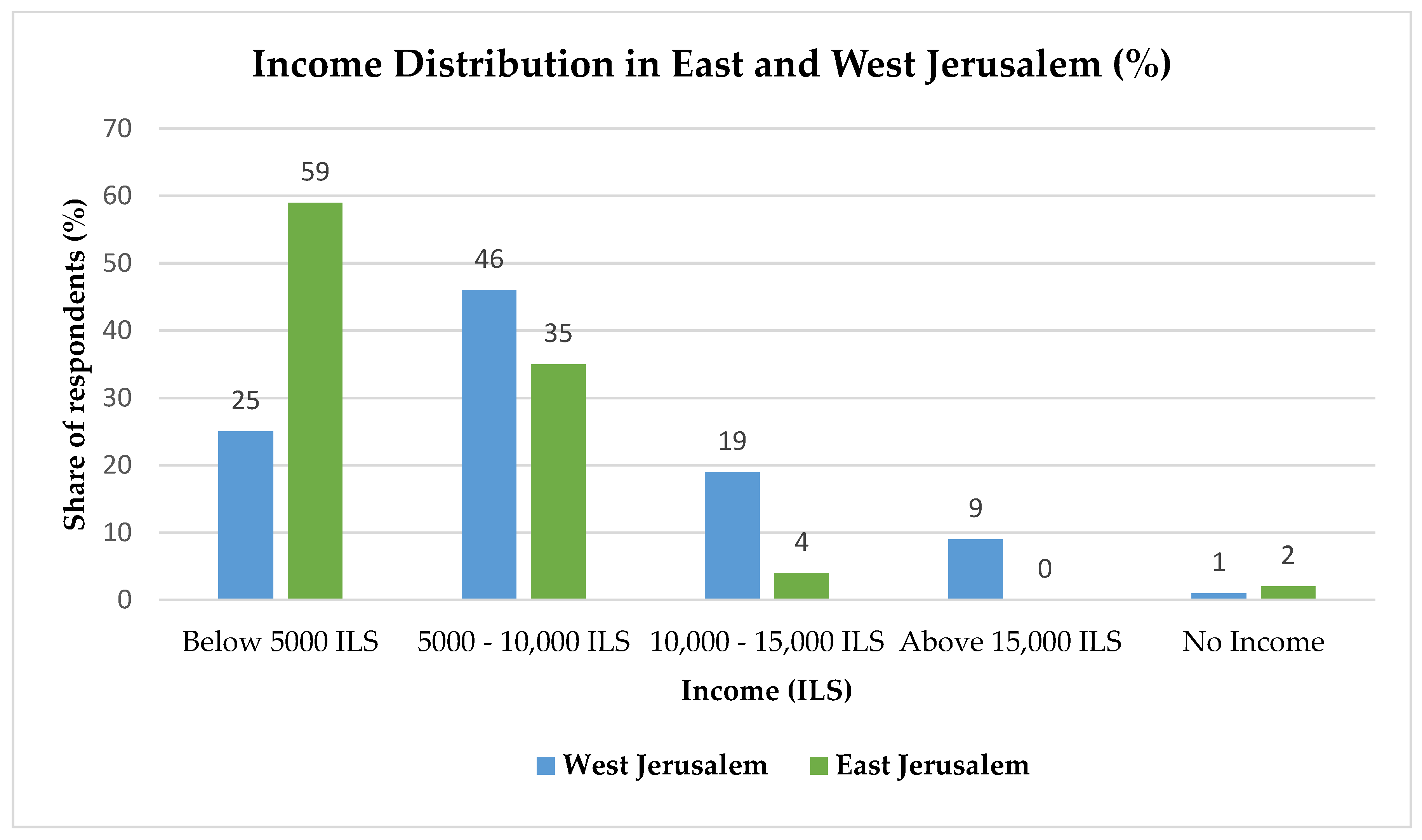

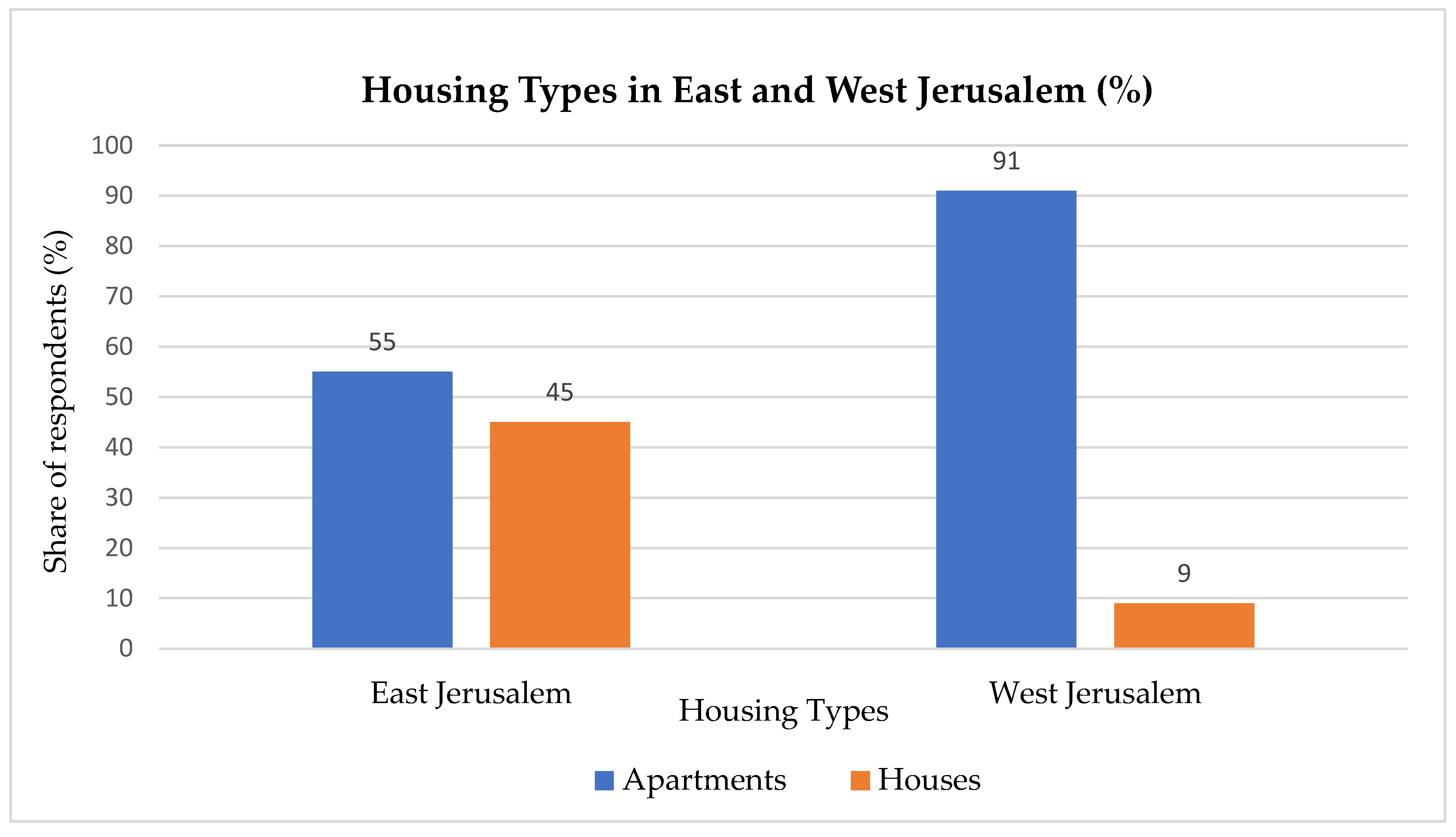

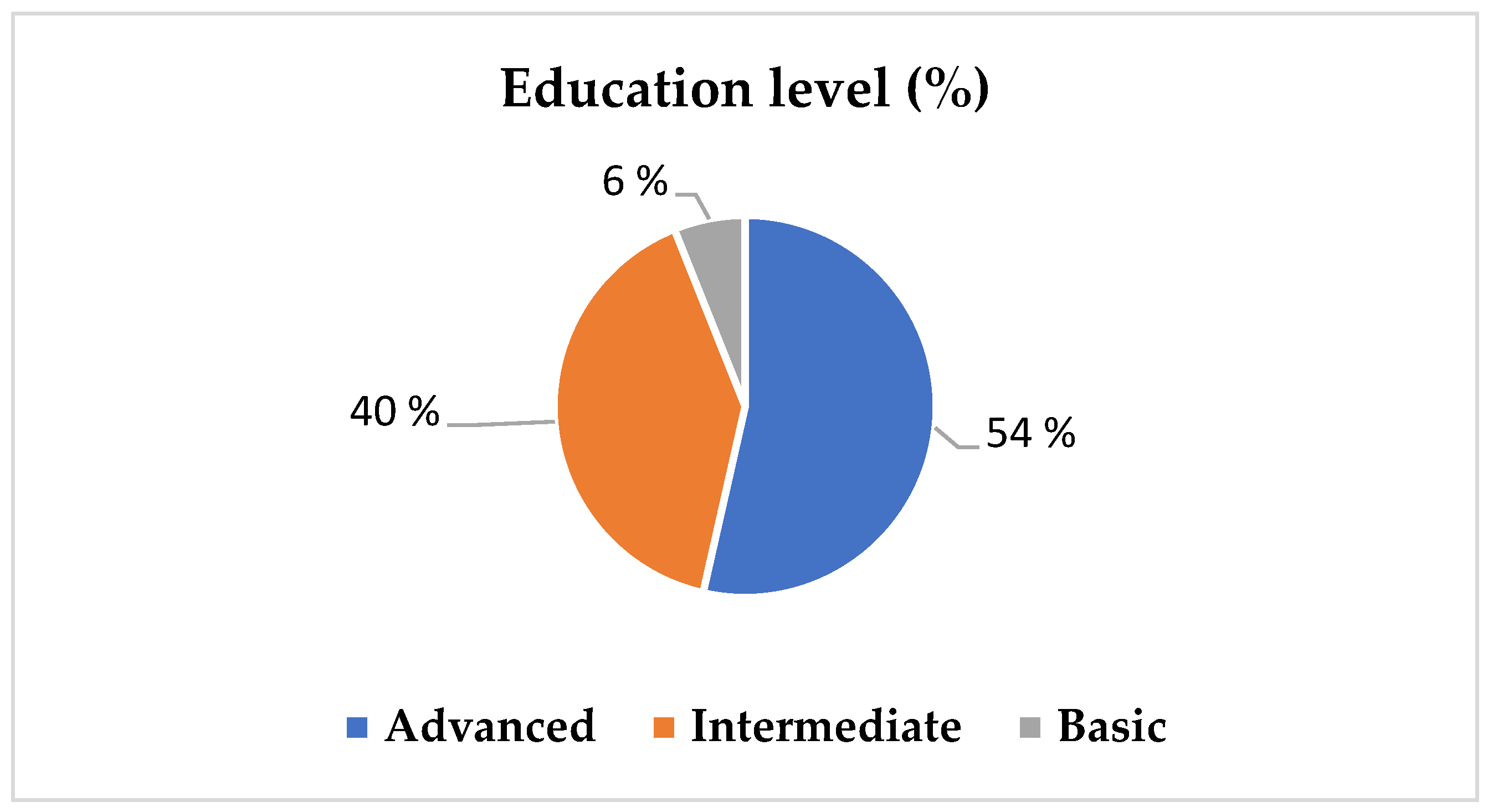

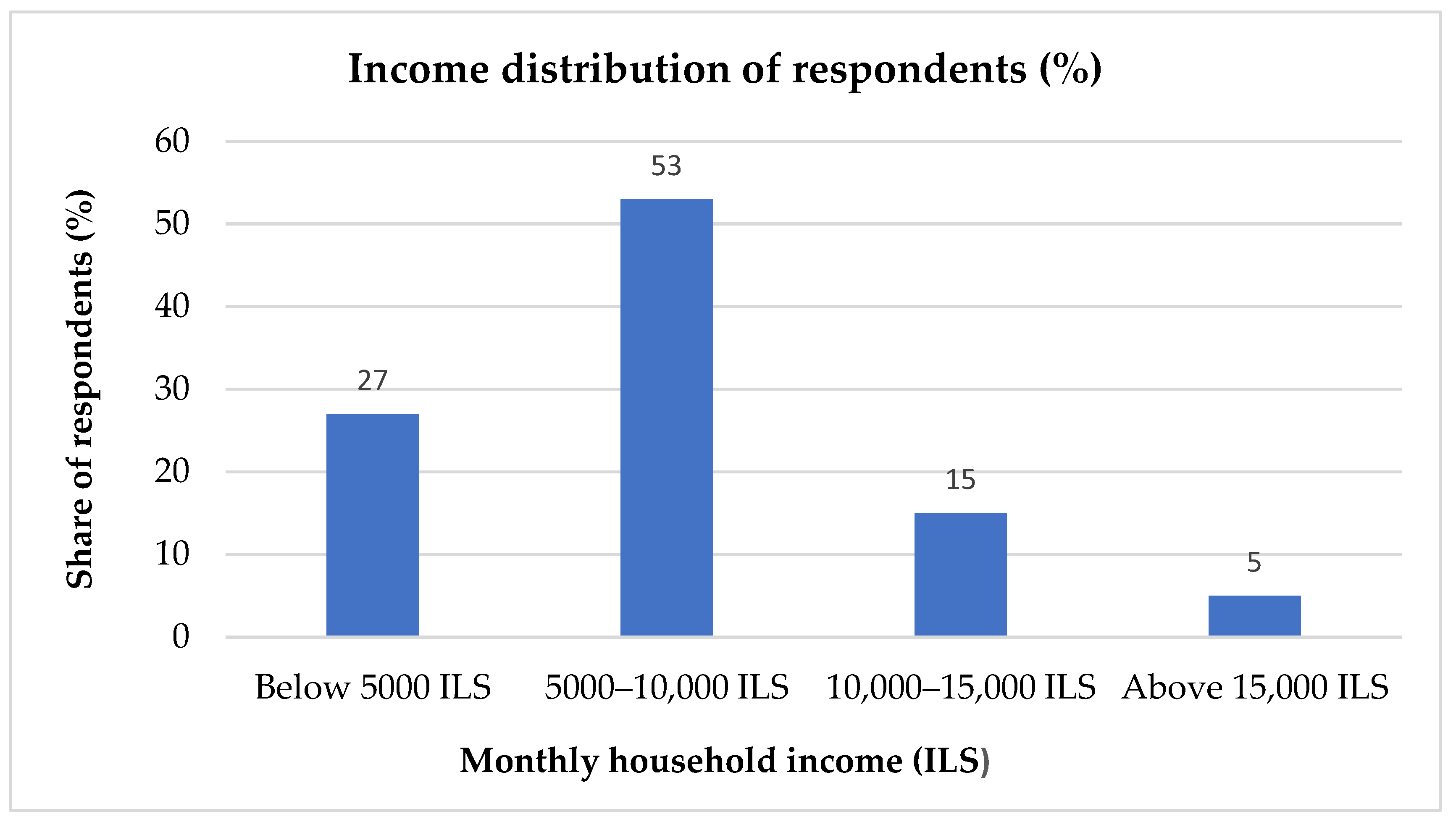

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents

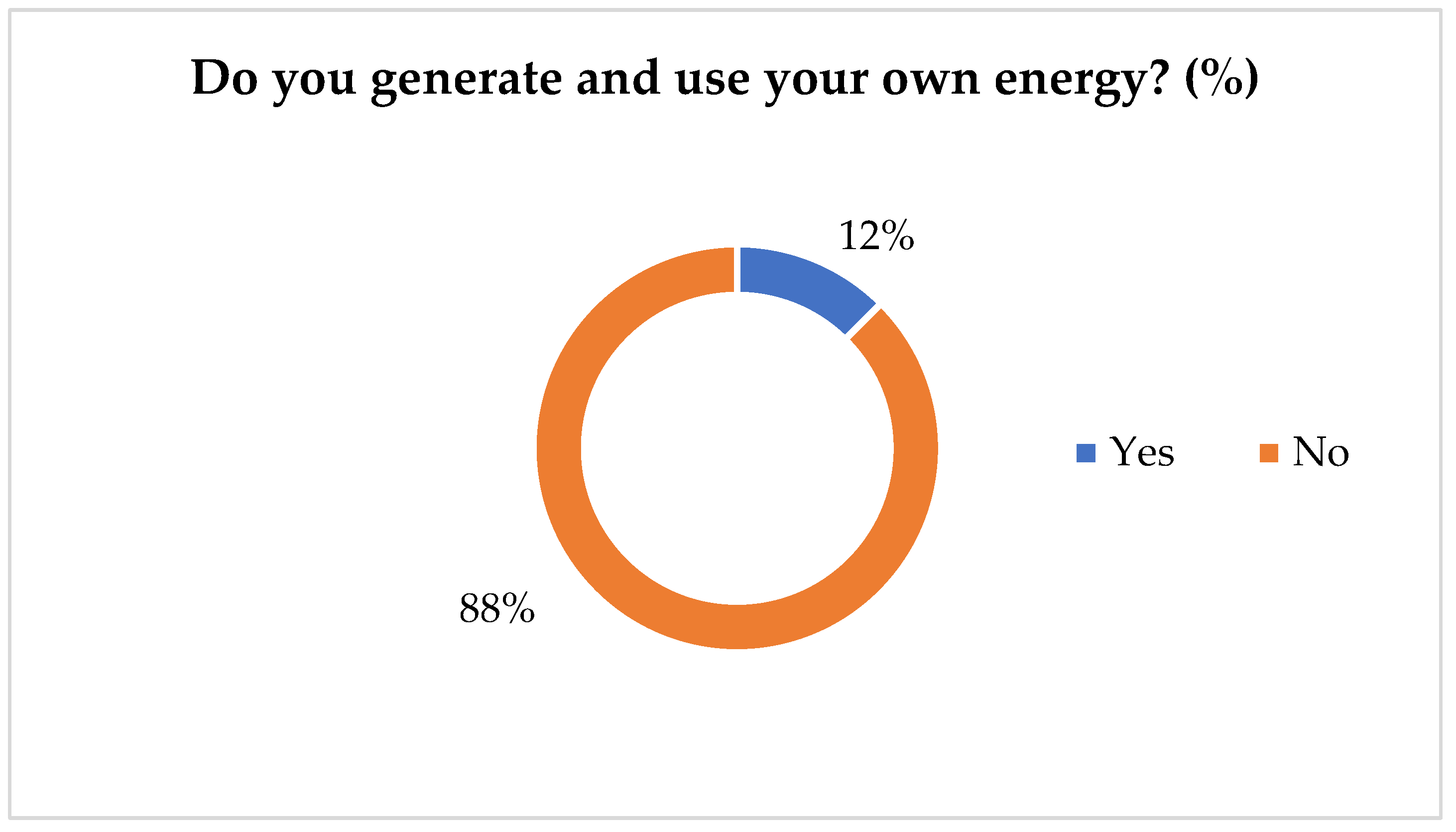

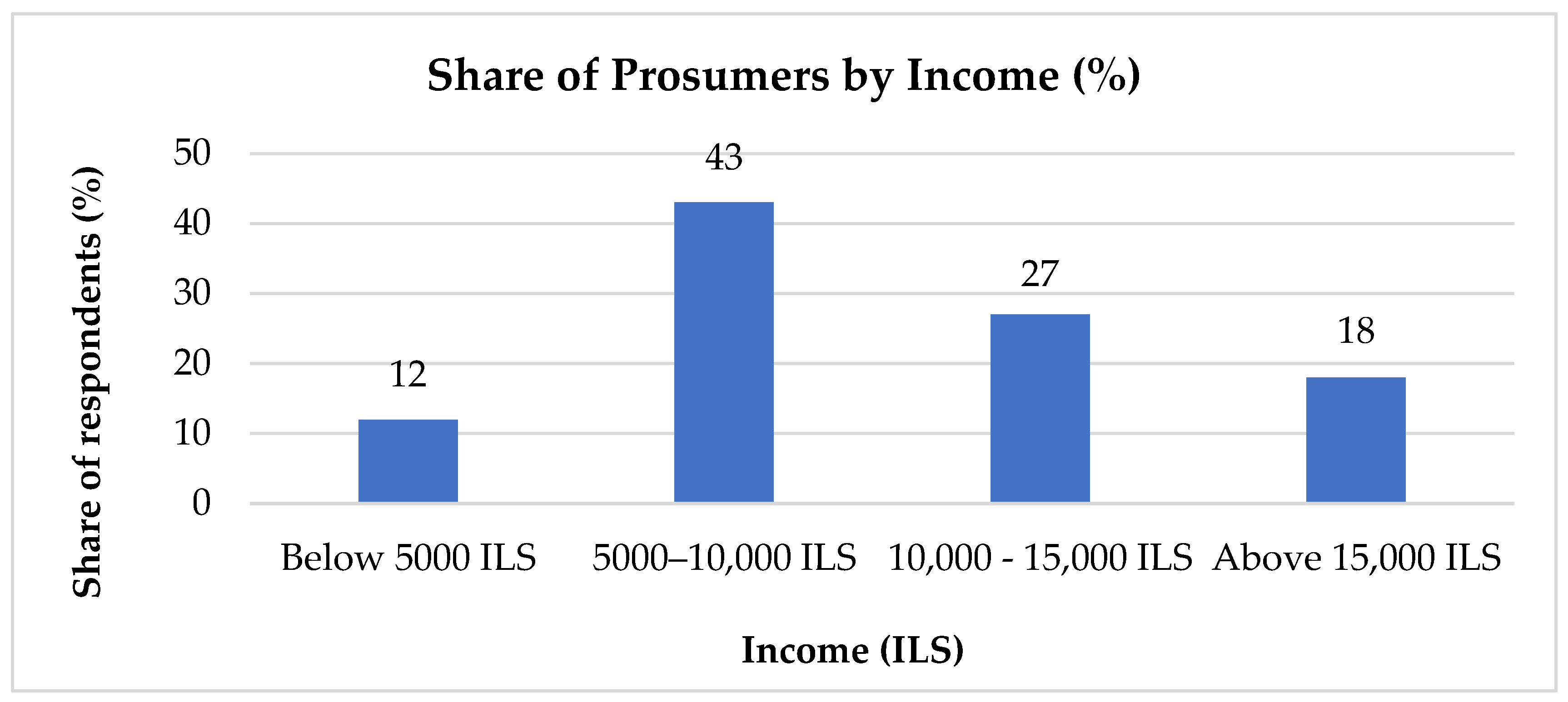

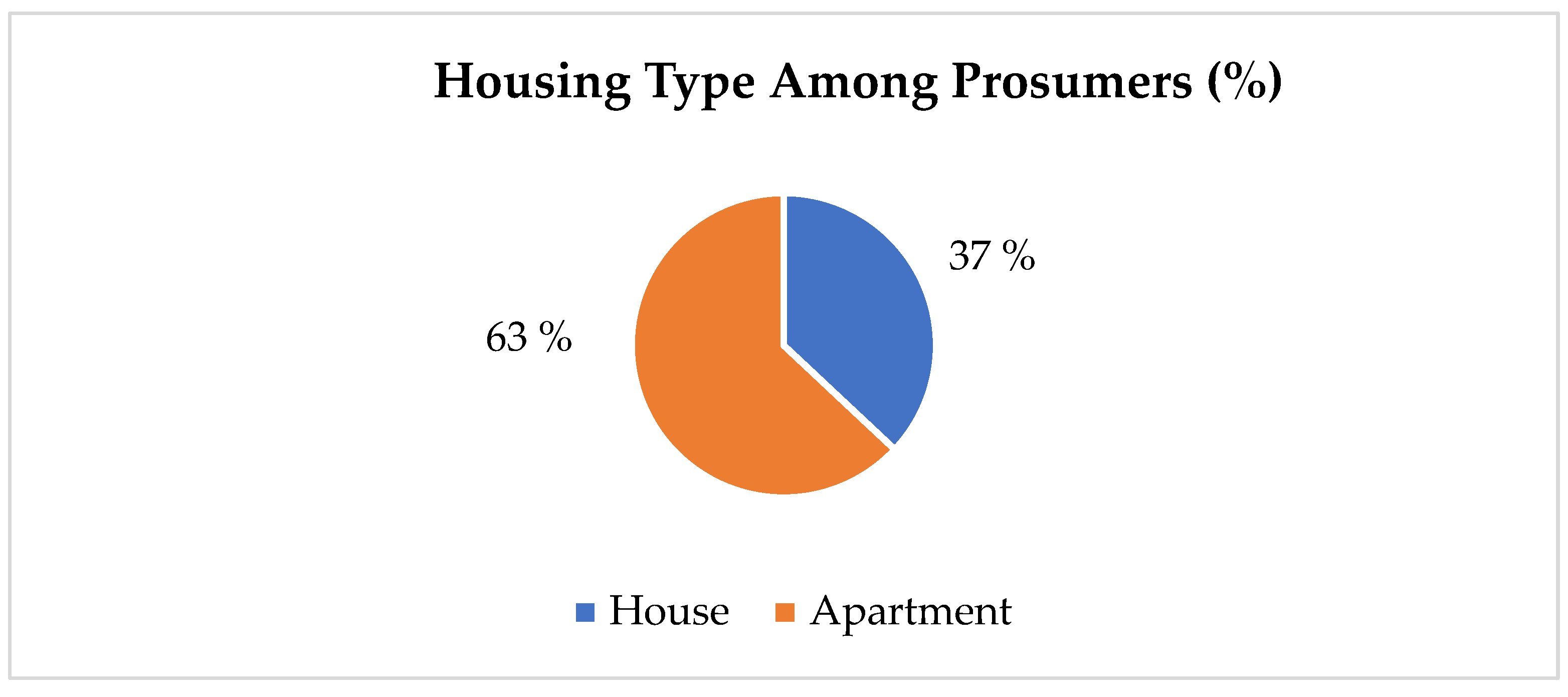

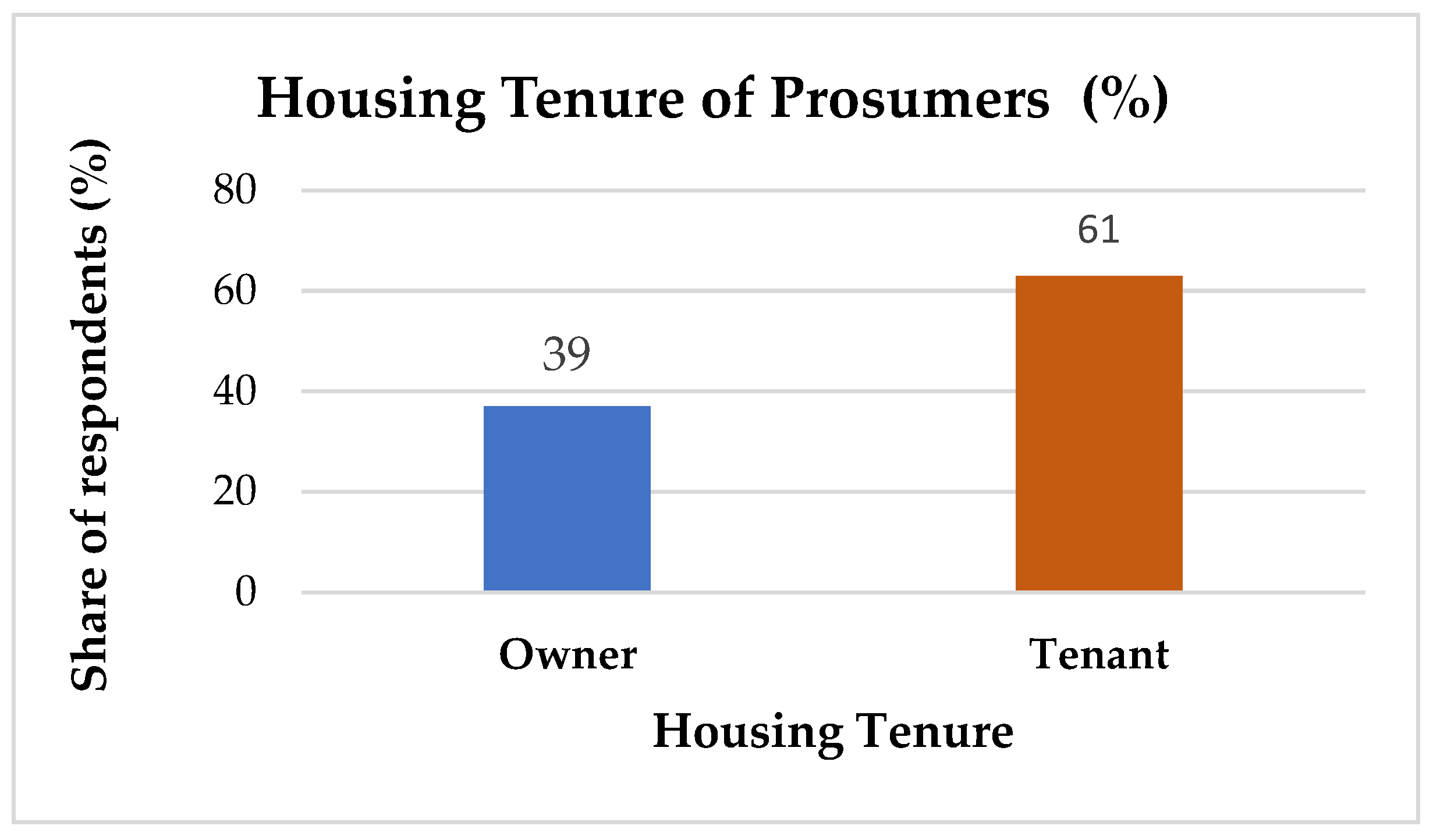

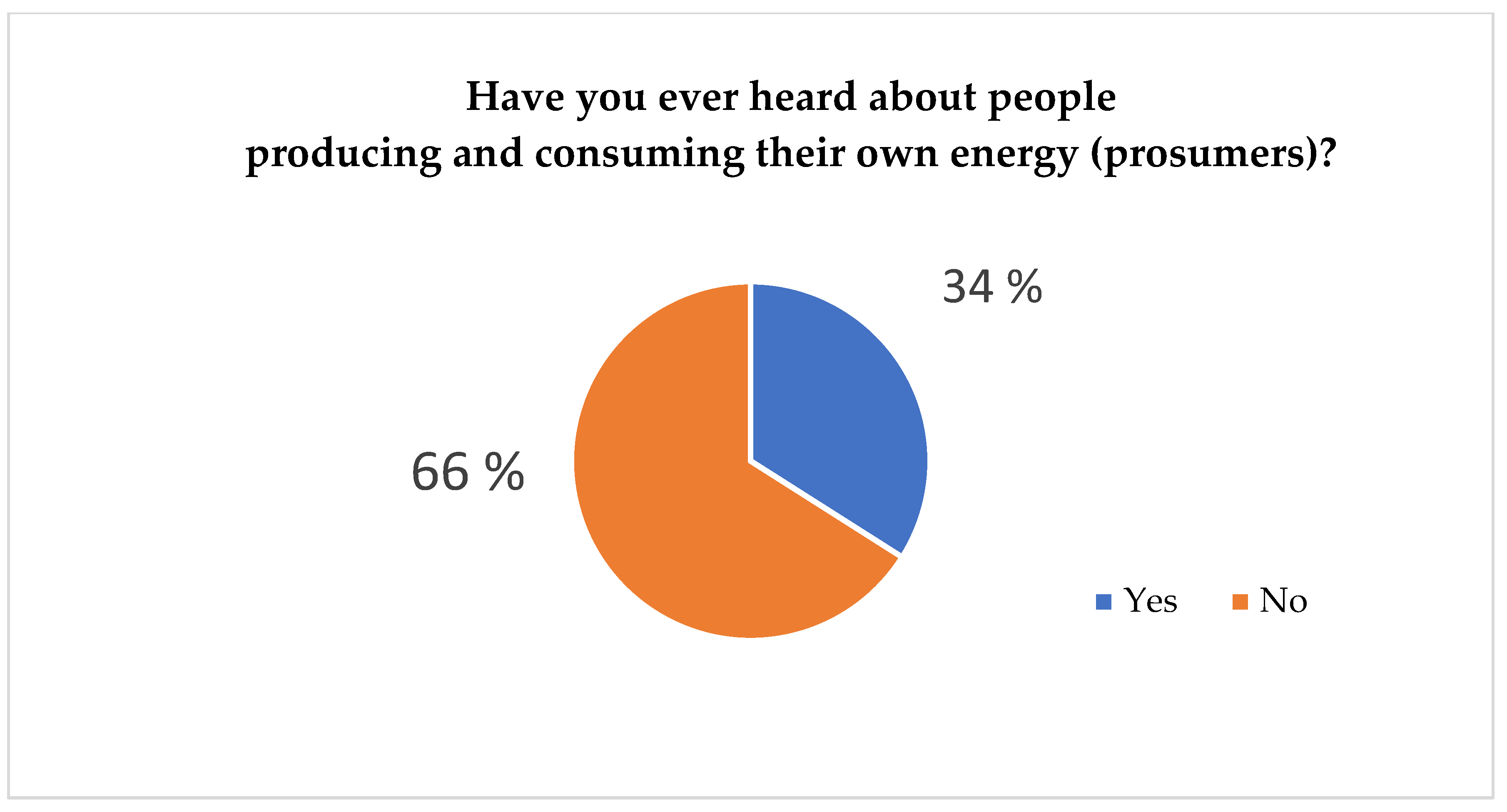

4.2. Current Energy Prosumerism Practice

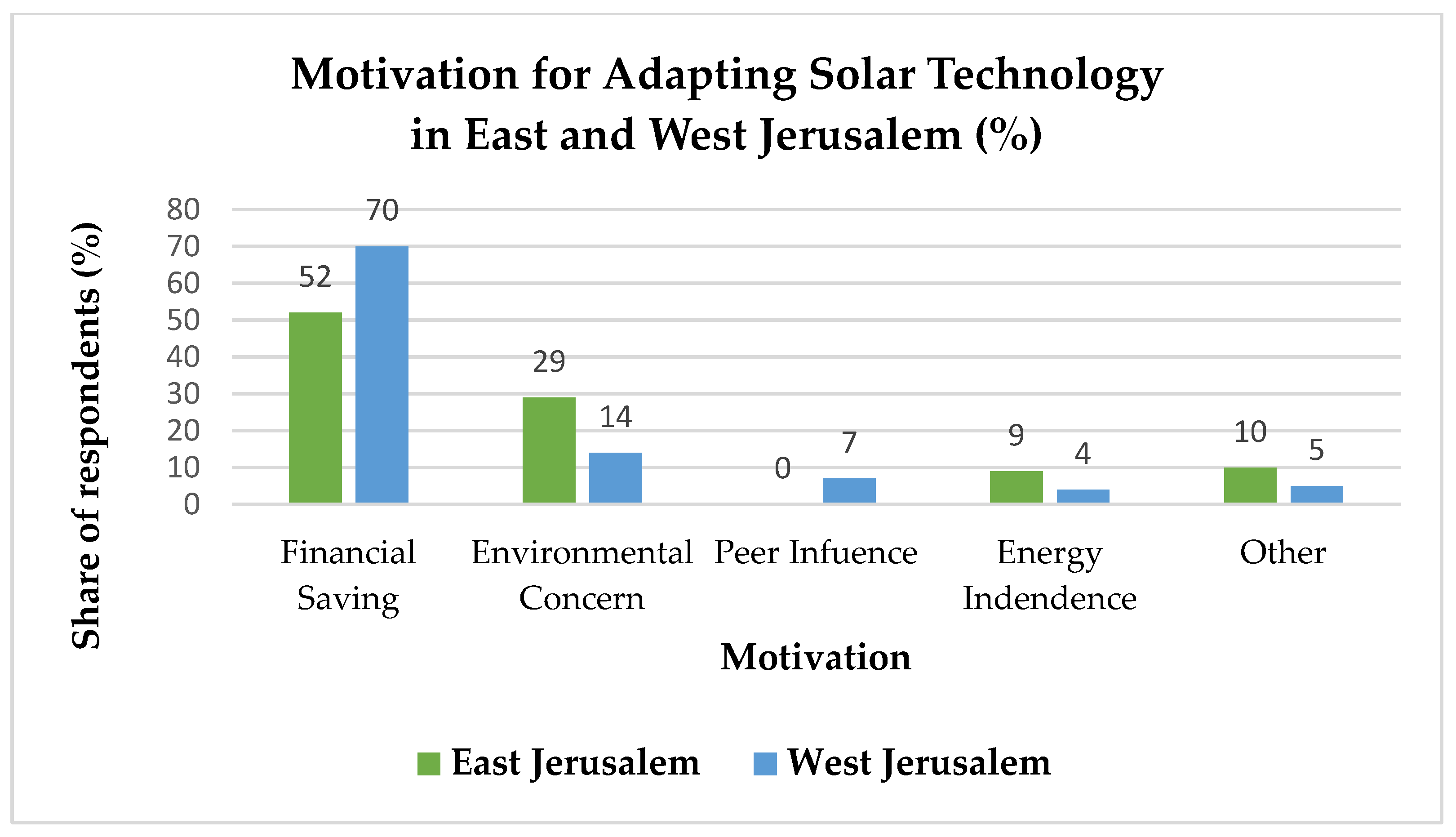

4.3. Motivational Drivers and Constraint Factors

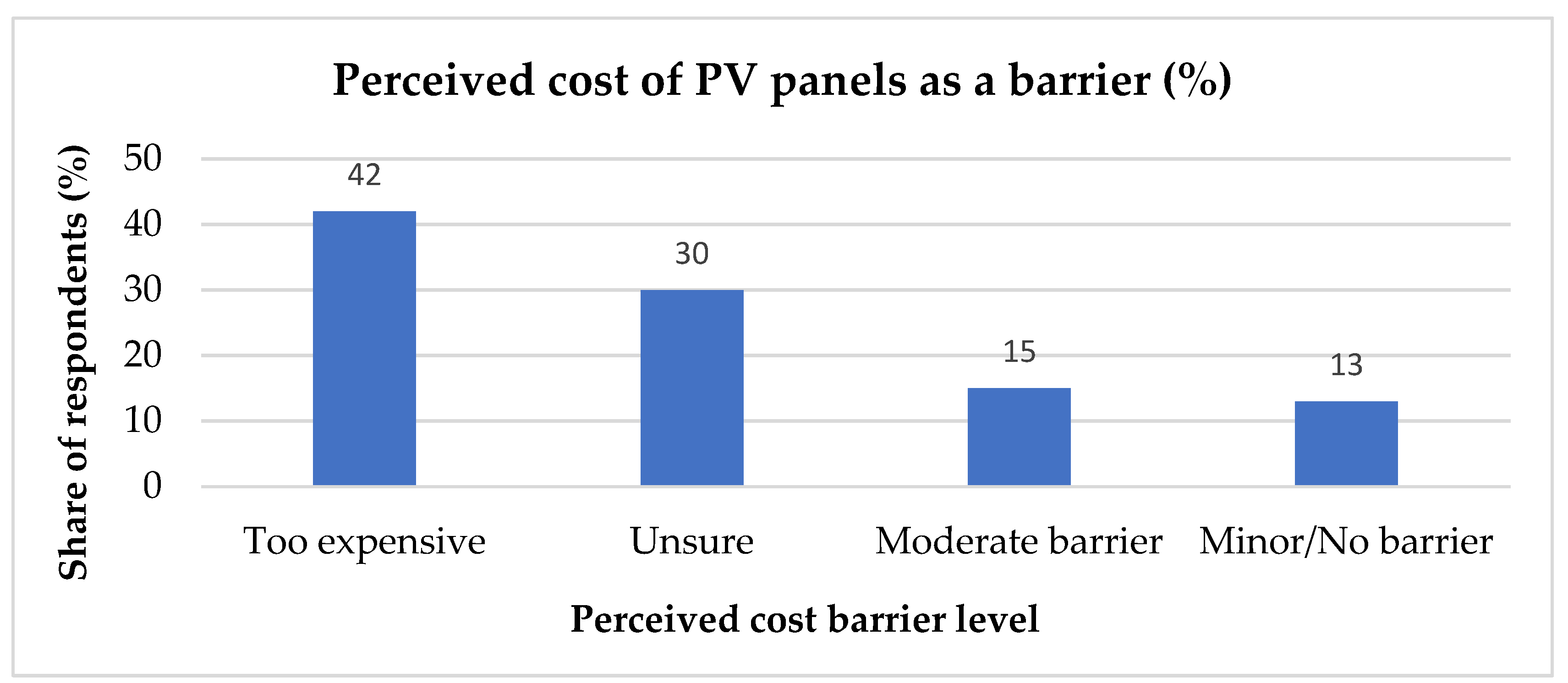

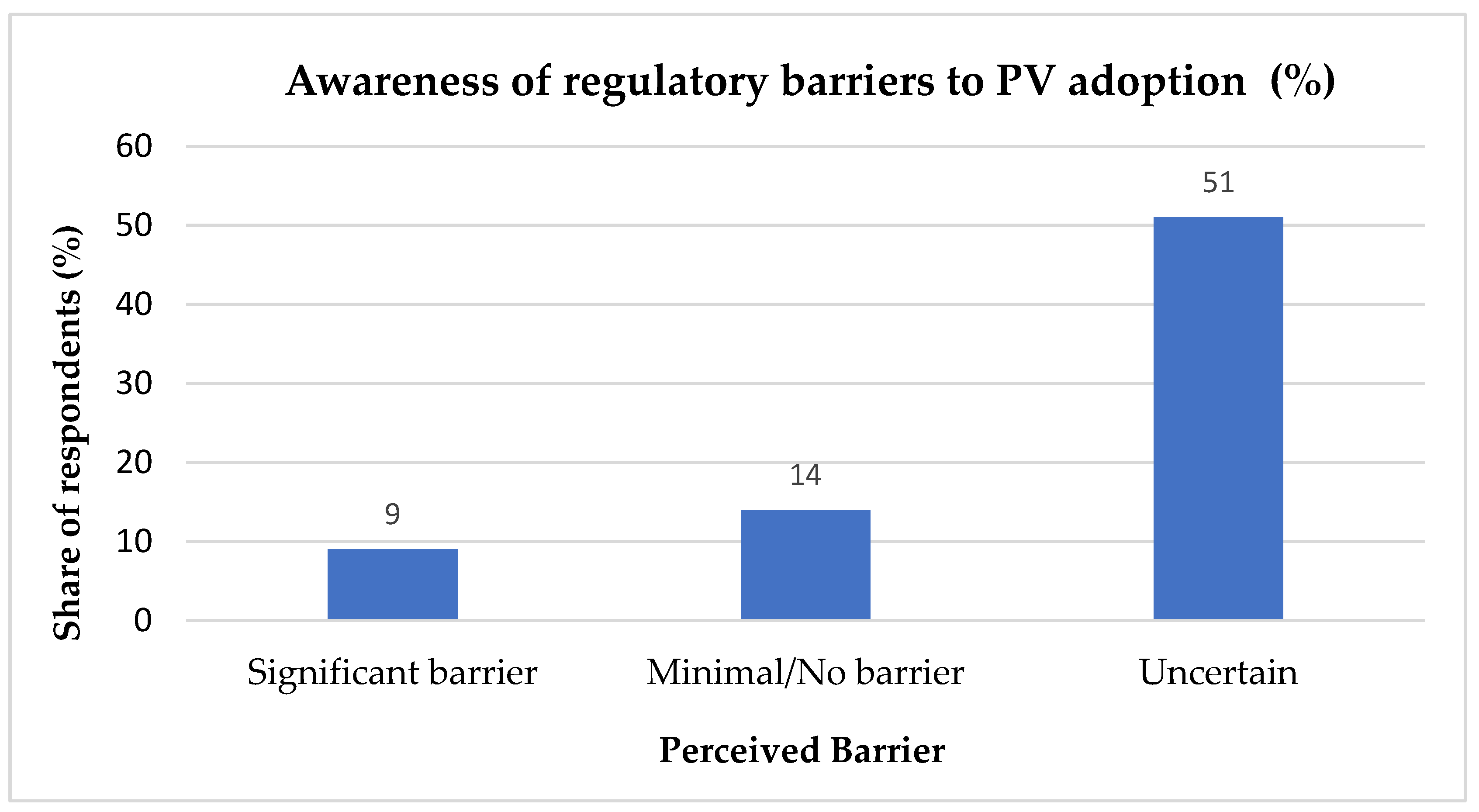

4.4. Barriers to Adopting Solar Energy Systems

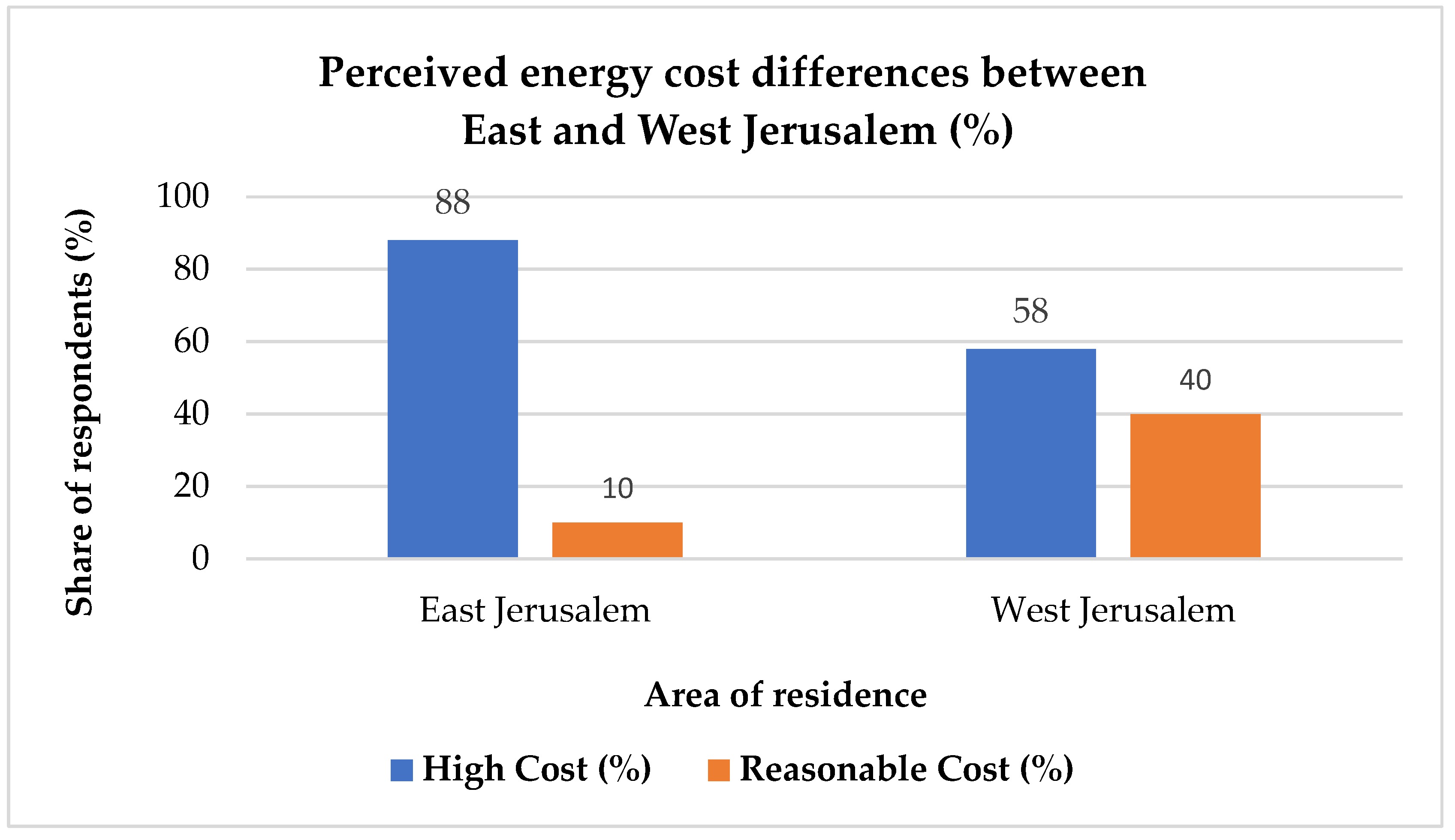

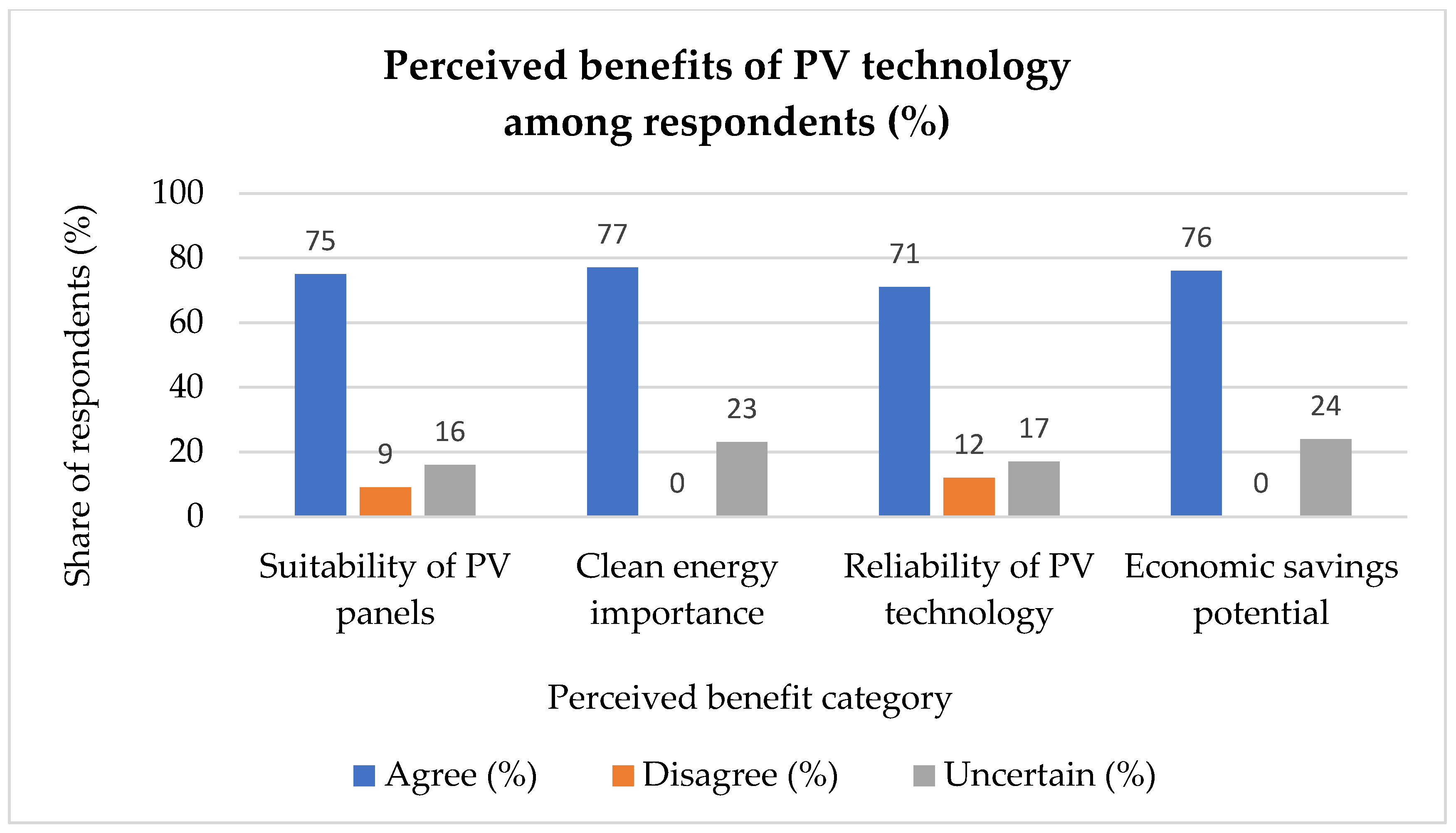

4.5. Perception of PV Technology

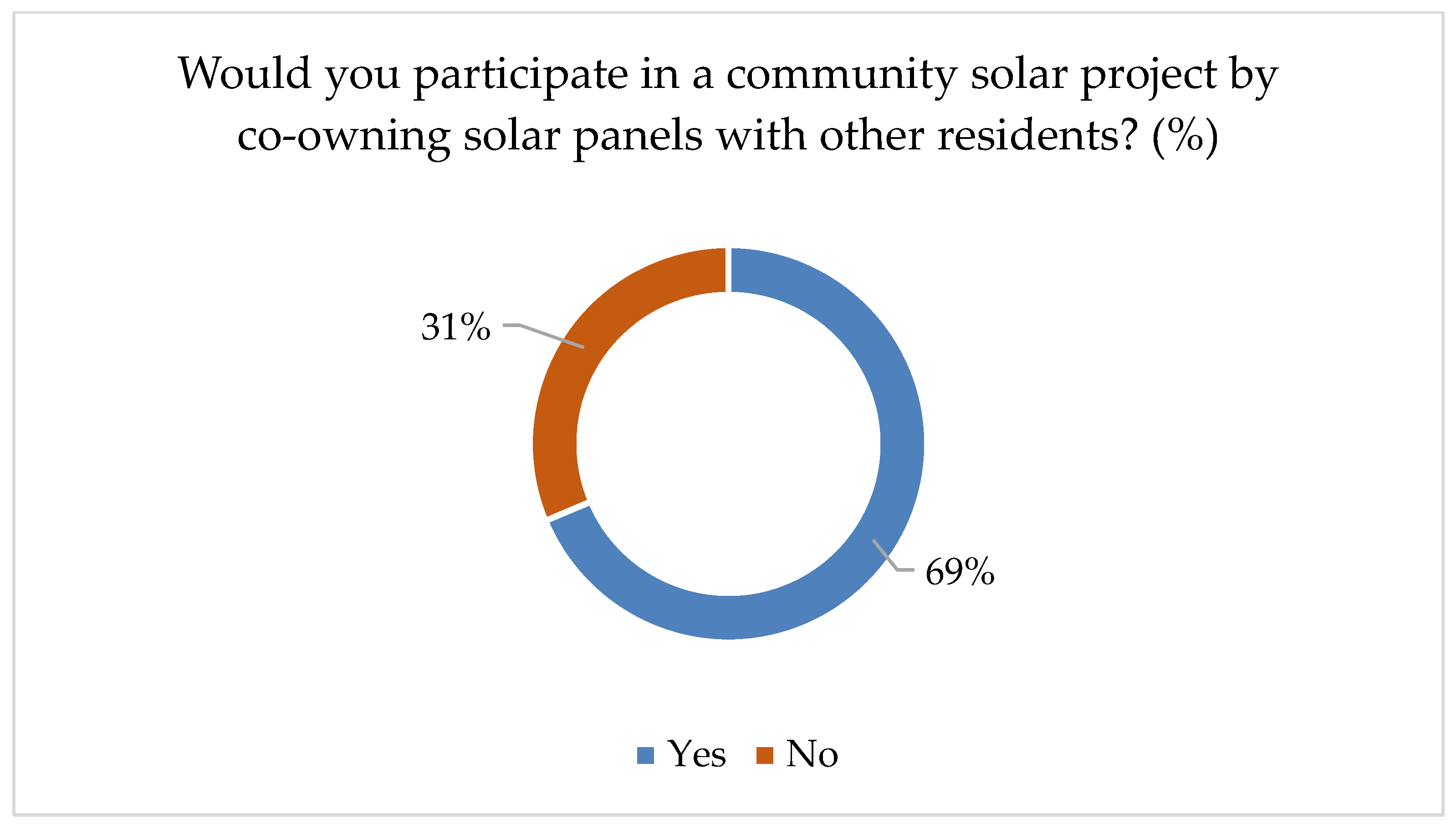

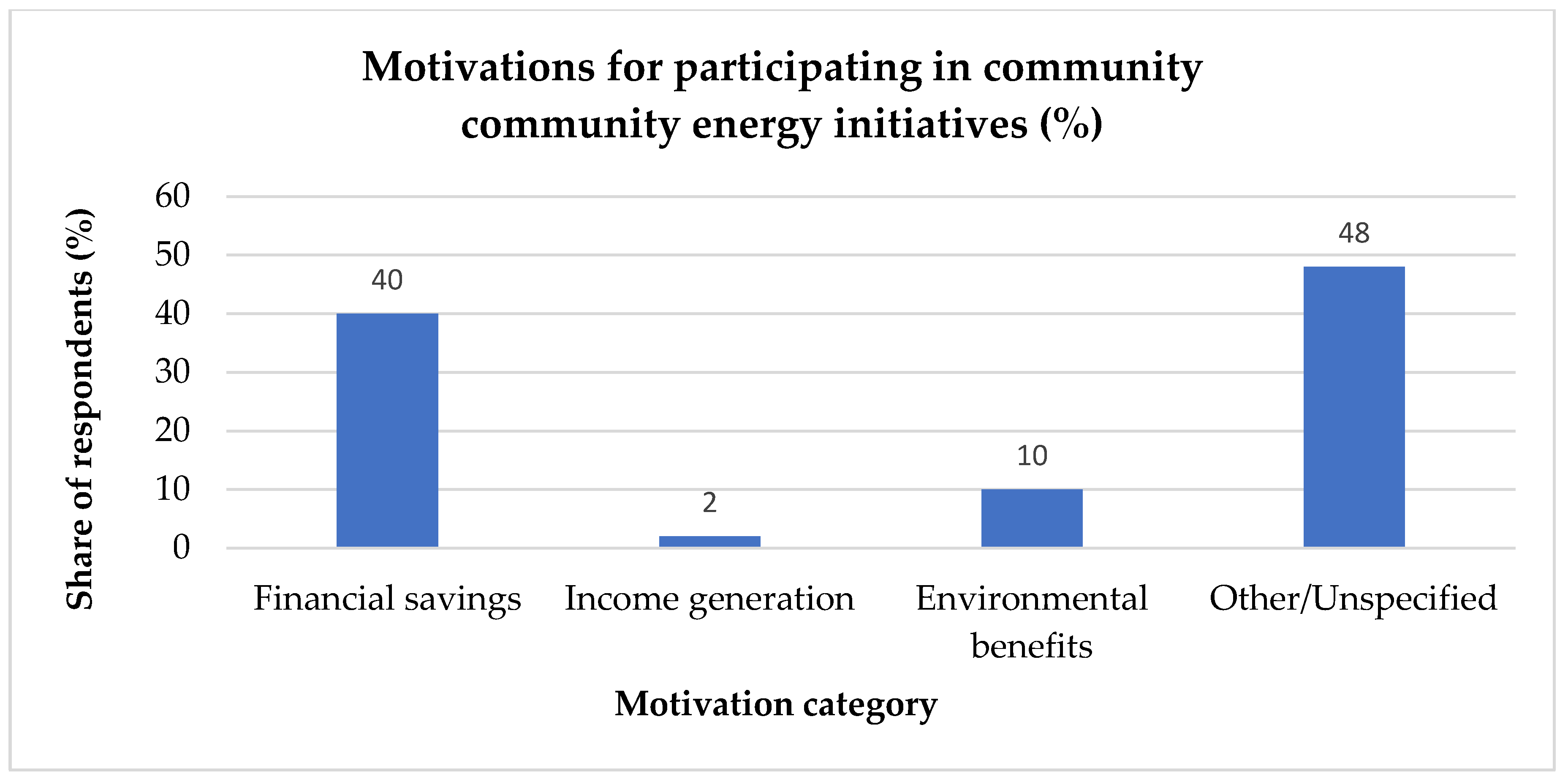

4.6. Community Engagement and Prosumerism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. Empowering Urban Energy Transitions Smart Cities and Smart Grids; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/empowering-urban-energy-transitions (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Nik, V.M.; Perera, A.T.D.; Chen, D. Towards climate resilient urban energy systems: A review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Nobanee, H.; Ullah, S.; Iftikhar, H. Renewable energy transition and regional integration: Energizing the pathway to sustainable development. Energy Policy 2024, 193, 114270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, M.L.; Favuzza, S.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Zizzo, G. How Decarbonization, Digitalization and Decentralization are changing key power infrastructures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, A.; Sijm, J.; Faaij, A. A systemic approach to analyze integrated energy system modeling tools: A review of national models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Yin, X. Understanding the impact on energy transition of consumer behavior and enterprise decisions through evolutionary game analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, S.; Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Z. Multidimensional assessment of energy transition and policy implications. Renew. Energy 2025, 238, 121870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, E.; Chtourou, N.; Bazin, D. Technological, economic, institutional, and psychosocial aspects of the transition to renewable energies: A critical literature review of a multidimensional process. Renew. Energy Focus 2022, 43, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Sovacool, B.K. How long will it take? Conceptualizing the temporal dynamics of energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, R. Historical energy transitions: Speed, prices and system transformation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, J.; Lipscy, P.Y.; Finnegan, J.J.; Metz, F. Why nations lead or lag in energy transitions. Science 2022, 378, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, J.; Kern, F.; Rogge, K. The need for comprehensive and well targeted instrument mixes to stimulate energy transitions: The case of energy efficiency policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 33, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlund, M.; Palm, J. The role of energy democracy and energy citizenship for participatory energy transitions: A comprehensive review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 87, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Demski, C.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W. A people-centred approach is needed to meet net zero goals. J. Br. Acad. 2023, 11, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprotti, F.; de Groot, J.; Mathebula, N.; Butler, C.; Moorlach, M. Wellbeing, infrastructures, and energy insecurity in informal settlements. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1388389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffler, A. The Third Wave, 1st ed.; Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T.; de Vries, G. Social innovation and the energy transition. Sustainability 2018, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; de Geus, T.; Pel, B.; Avelino, F.; Hielscher, S.; Hoppe, T.; Mühlemeier, S.; Stasik, A.; Oxenaar, S.; Rogge, K.S.; et al. Beyond instrumentalism: Broadening the understanding of social innovation in socio-technical energy systems. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.J.; Bradley, N.; Compagnucci, A.B.; Barlagne, C.; Ceglarz, A.; Cremades, R.; McKeen, M.; Otto, I.M.; Slee, B. Social innovation in community energy in Europe: A review of the evidence. Front Energy Res. 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, A.N.; Slee, B.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn, M.; Nijnik, M.; Gezik, V. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Call: H2020-ISIB-2015-2 Innovative, Sustainable and Inclusive Bioeconomy—Report D2.1 Classification of Social Innovations for Marginalized Rural Areas. 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/D2.1-Classification-of-SI-for-MRAs-in-the-target-region.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Riveros, J.Z.; Scacco, P.M.; Ulli-Beer, S. Network dynamics of positive energy districts: A coevolutionary business ecosystem analysis. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1266126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhon, M.; Murphy, J.T. Socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions: Insights from political ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 36, 354–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Longhurst, N. Participation in transition(s): Reconceiving public engagements in energy transitions as co-produced, emergent and diverse. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Energy Citizenship: Psychological Aspects of Evolution in Sustainable Energy Technologies. In Governing Technology for Sustainability, 1st ed.; Murphy, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaValle, N.; Czako, V. Empowering energy citizenship among the energy poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvast, A.; Valkenburg, G. Energy citizenship: A critical perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 98, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryghaug, M.; Skjølsvold, T.M.; Heidenreich, S. Creating energy citizenship through material participation. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2018, 48, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunphy, N.P.; Lennon, B.; Revez, A.; Pearce, B.B.J. Conceptualising Energy Citizenship. In Energy Citizenship; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, N.P.; Lennon, B.; Revez, A.; Pearce, B.B.J. Participation and Energy Citizenship. In Energy Citizenship; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Demir, M.H.; Solak, B.; Savas, Z.F.; Kollmann, A.; Kirchler, B.; Ozcureci, B. Empowering energy citizenship: Exploring dimensions and drivers in citizen engagement during the energy transition. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1894–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Marín-González, E. People in transitions: Energy citizenship, prosumerism and social movements in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Korsnes, M.; Labanca, N.; Bertoldi, P. Can renewable energy prosumerism cater for sufficiency and inclusion? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 197, 114410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R. I’ll follow the sun: Geo-sociotechnical constraints on prosumer households in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annuk, A.; Yaïci, W.; Blinov, A.; Märss, M.; Trashchenkov, S.; Miidla, P. Modelling of consumption shares for small wind energy prosumers. Symmetry 2021, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzevic, S.; Tausova, M.; Culkova, K.; Domaracka, L.; Shyp, D. Energy Efficiency in Heat Pumps and Solar Collectors: Case of Slovakia. Processes 2024, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.A.; Bosman, L.B.; Wollega, E.; Leon-Salas, W.D. Peer-to-peer energy trading: A review of the literature. Appl. Energy 2021, 283, 116268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Innovation Landscape Brief: Peer-to-Peer Electricity Trading; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Jul/IRENA_Peer-to-peer_electricity_trading_2020.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- EESC. Delivering a New Deal for Energy Consumers (Communication). 2016. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/delivering-new-deal-energy-consumers-communication (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- EEA. Energy Prosumers in Europe—Citizen Participation in the Energy Transition. September 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/the-role-of-prosumers-of (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Promotion of Energy from Renewable Sources, and Repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32023L2413 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- de Brauwer, C.P.-S.; Cohen, J.J. Analysing the potential of citizen-financed community renewable energy to drive Europe’s low-carbon energy transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, B.; Dunphy, N.P.; Sanvicente, E. Community acceptability and the energy transition: A citizens’ perspective. Energy Sustain Soc. 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Hall, S.; Davis, M.E. What is prosumerism for? Exploring the normative dimensions of decentralised energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 66, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berka, A.; Dreyfus, M. Decentralisation and inclusivity in the energy sector: Preconditions, impacts and avenues for further research. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.; Soares, T.; Pinson, P.; Moret, F.; Baroche, T.; Sorin, E. Peer-to-peer and community-based markets: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitzow, L. Smart grids, smart households, smart neighborhoods–contested narratives of prosumage and decentralization in Berlin’s urban Energiewende. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 36, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpfenbach, K.; Faber, R. StromNachbarn: Evaluation der sozialen und ökologischen Wirkungen von Mieterstromanlagen in Berlin. Berlin 2021. Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/17805 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Ingo, B. Hagemann, Solarsiedlung am Schlierberg, Freiburg (Breisgau), Germany. 2007. Available online: https://rue-avenir.ch/wp-content/uploads/files/resources/Cite-solaire-Schlierberg.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Coates, G.J. The sustainable Urban district of vauban in Freiburg, Germany. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2013, 8, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, S. The (Non) impact of the Spanish ‘Tax on the Sun’ on photovoltaics prosumers uptake. Energy Policy 2022, 168, 113041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño-Rodriguez, A.; Ramallo-González, A.P.; Chinchilla-Sánchez, M.; Molina-García, A. Community energy solutions for addressing energy poverty: A local case study in Spain. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Castillo, C.; Heleno, M.; Victoria, M. Self-consumption for energy communities in Spain: A regional analysis under the new legal framework. Energy Policy 2021, 150, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, J. New Municipalism and the State: Remunicipalising Energy in Barcelona, from Prosaics to Process. Antipode 2021, 53, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardakas, J.S.; Zenginis, I.; Zorba, N.; Echave, C.; Morato, M.; Verikoukis, C. Electrical Energy Savings through Efficient Cooperation of Urban Buildings: The Smart Community Case of Superblocks’ in Barcelona. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüwel, P.B.; Sotoca, A.; Palumbo, M. Towards a Balanced Energy Community. Matching Energy Supply and Demand Curves. Ways of Governance. Archit. City Environ. 2025, 19, 12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadeço, M.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Ferrão, P.; Luz, G.; Freitas, S.; Brito, M.C. Solar Self-Consumption and Urban Energy Vulnerability: Case Study in Lisbon. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Jimenez, A.; Mehta, P.; Griego, D. Let it grow: How community solar policy can increase PV adoption in cities. Energy Policy 2023, 175, 113477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Christ, O. Household participation in an urban photovoltaic project in Switzerland: Exploration of triggers and barriers. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopfer, S. Assessment of the Consumer-Prosumer Transition and Peer-to-Peer Energy Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Orehounig, K. Design and assessment of district heating systems with solar thermal prosumers and thermal storage. Energies 2021, 14, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, L.; Parag, Y. Motivations and barriers to integrating ‘prosuming’ services into the future decentralized electricity grid: Findings from Israel. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS. Labour Force Survey Data, November 2023. Jerusalem, December 2023. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2023/414/20_23_414e.docx (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Statista. Monthly Number of International Tourists Arriving in Israel from January 2022 to September 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1473422/israel-monthly-tourist-arrivals/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Shahar, T.; Lerer, M. Updated Data on Evacuees from the North and South (נתונים מעודכנים על מפונים מהצפון ומהדרום). Jerusalem. July 2024. Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/bb4ad946-3c2d-ef11-815f-005056aac6c3/2_bb4ad946-3c2d-ef11-815f-005056aac6c3_11_20597.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Roumani, H. Biodiversity Report—City of Jerusalem (2013). Jerusalem, 2013. Available online: https://cbc.iclei.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Jerusalem-Biodiversity-Report_2013.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- CBS. Selected Data on the Occasion of Jerusalem Day, 2024. Jerusalem, June 2024. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2024/165/11_24_165e.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; et al. Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMS. Climate Atlas of Israel. Available online: https://ims.gov.il/en/ClimateAtlas (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Electricity Authority. Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (2023). September 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/dochmeshek/he/Files_doch_meshek_hashmal_IEC_AnnualReport_2022_nnn.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Electricity Authority. Report on the State of the Electricity Sector (2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/dochmeshek/he/Files_doch_meshek_hashmal_doch_meshek_2023_nnn.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kádár, J.; Pilloni, M.; Hamed, T.A. A Survey of Renewable Energy, Climate Change, and Policy Awareness in Israel: The Long Path for Citizen Participation in the National Renewable Energy Transition. Energies 2023, 16, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute. The Implications of the Electricity Sector Dilemma Between the Public and Private Sectors: The Case of the Jerusalem District Electricity Company (JDECO). 2019. Available online: https://mas.ps/cached_uploads/download/migrated_files/20191012104921-1-1640017464.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Moss, T.; Fischhendler, I.; Herman, L.; Lukin, S.; Papasozomenou, O.; Rettig, E.; Rosen, G.; Shtern, M.; Sonan, S. Energy infrastructures in divided cities. Prog. Plan. 2024, 191, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtern, M.; Herman, L.; Fischhendler, I.; Rosen, G. Infrastructure sovereignty: Battling over energy dominance in Jerusalem. Territ. Politics Gov. 2022, 13, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem Municipality and Department for Strategic Planning and Environmental Policy. Adaptation to Climate Change and Promoting Sustainable Energy in Jerusalem 2030; Jerusalem Municipality and Department for Strategic Planning and Environmental Policy: Jerusalem, Israel, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. Local Authorities Index for Renewable Energy in Dual Use. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYmNjY2I5ZmMtYTUxYi00YjZhLWFmZTktOTgyMzE4MDkzZDNmIiwidCI6ImUxYjY2OThlLTlhMTQtNDNkOC05ZWJhLTUzNDBiZjc5MDkxMCIsImMiOjl9 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Government of Israel. Government Decision No. 1515: Reform of the Electricity Sector. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/pages/dec1515_2022 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- UNESCO. International Standards Classification of Education—ISCED 2011. 2012. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Bank of Israel. Exchange Rates. Available online: https://www.boi.org.il/en/economic-roles/financial-markets/exchange-rates/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- IEA. Regulation on Domestic Solar Water—Heaters. Available online: https://www.iea.org/policies/4307-regulation-on-domestic-solar-water-heaters (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Martínez, A.M.; Thiel, C.; Szabo, S.; Gherboudj, I.; van Swaaij, R.; Tanasa, A.; Jäger-Waldau, A.; Taylor, N.; Smets, A. The Role of Education and Science-Driven Tools in Scaling Up Photovoltaic Deployment. Energies 2023, 16, 8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreavesn, T.; Nye, M.; Burgess, J. Making energy visible: A qualitative field study of how householders interact with feedback from smart energy monitors. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6111–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambati, F.; Ruscio, D.; Biassoni, F.; Hueting, R.; Tedeschi, A. Predicting acceptance and adoption of renewable energy community solutions: The prosumer psychology. Open Res. Eur. 2022, 2, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penco, L.; Bruzzi, C. Individuals’ Willingness to Become a Prosumer of Green Energy: An Explorative Study and Research Agenda. In Business for Sustainability, Volume II: Contextual Evolution and Elucidation; Vrontis, D., Thrassou, A., Efthymiou, L., Weber, Y., Shams, S.M.R., Tsoukatos, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. Household energy use: Applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebben, D.; Peters, J.F. Communicating the Values and Benefits of Home Solar Prosumerism. Energies 2022, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klingeren, F.; De Moor, T. Ecological, financial, social and societal motives for cooperative energy prosumerism: Measuring preference heterogeneity in a Belgian energy cooperative. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Vargas, A.; Cansino, J.M.; Román-Collado, R. Economic and environmental analysis of a residential PV system: A profitable contribution to the Paris agreement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, P.; Carrete, L. Motivational drivers for the adoption of green energy: The case of purchasing photovoltaic systems. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 542–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, J.Z.; Kubli, M.; Ulli-Beer, S. Prosumer communities as strategic allies for electric utilities: Exploring future decentralization trends in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, H.; Okpara, K.; Choochuay, C.; Kuaanan, T. Energy consumers barriers/motivations to becoming a prosumer. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Aravena, J.C.; de la Casa, J.; Töfflinger, J.A.; Muñoz-Cerón, E. Identifying barriers and opportunities in the deployment of the residential photovoltaic prosumer segment in Chile. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, J. Peer-to-peer (P2P) electricity trading in distribution systems of the future. Electr. J. 2019, 32, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanayake, R.; Johnson, L.; Daronkola, H.K.; Perera, C. Impact of Households’ Future Orientation and Values on Their Willingness to Install Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.; Emmerich, P.; Baumann, M.J.; Weil, M. Assessing the social acceptance of key technologies for the German energy transition. Energy Sustain Soc. 2022, 12, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Zeng, S.; Irfan, M.; Peng, R. Do Perceived Risk, Perception of Self-Efficacy, and Openness to Technology Matter for Solar PV Adoption? An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavio. Energies 2021, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Bello, A.; Parra, D.; Herberz, M.; Tiefenbeck, V.; Patel, M.K.; Hahnel, U.J.J. Integration of prosumer peer-to-peer trading decisions into energy community modelling. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.-J. Detecting Prosumer-Community Groups in Smart Grids from the Multiagent Perspective. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. ‘Let’s do it ourselves’ Individual motivations for investing in renewables at community level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| Demographic Information | Gender; Age; City of Residence; Level of Education; Income, Housing Types, and Tenure |

| Awareness of Prosumerism | Familiarity with the Concept of Prosumerism; Perception of Self-Energy Production and Consumption |

| Current Prosumer Practice | Prosumer Activity and System Characteristics |

| Motivation to Become a Prosumer | Financial, Environmental, and Governmental Incentives for Installing Solar Technologies |

| Barriers to PV Adoption | Key Obstacles include Financial, Regulatory, Administrative and Grid Integration Issues |

| Perception of Electricity Prosumerism | Views on Sustainability, Affordability, and Long-term Benefits |

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Total Survey Participants | 320 |

| Participants from East Jerusalem | 102–31.9% |

| Participants from West Jerusalem | 218–68.1% |

| Gender Distribution | Male: 53%; Female: 47% |

| Age Distribution | Mean: 40 years; Median: 36 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kádár, J.; Pilloni, M.; Cornelis, M.; Bosman, L.; Riveros, J.V.Z.; Hamed, T.A.; Andreucci, M.B. From Passive Consumers to Active Citizens: A Survey-Based Study of Prosumerism in Jerusalem. Sustainability 2026, 18, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010481

Kádár J, Pilloni M, Cornelis M, Bosman L, Riveros JVZ, Hamed TA, Andreucci MB. From Passive Consumers to Active Citizens: A Survey-Based Study of Prosumerism in Jerusalem. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010481

Chicago/Turabian StyleKádár, József, Martina Pilloni, Marine Cornelis, Lisa Bosman, Juliana Victoria Zapata Riveros, Tareq Abu Hamed, and Maria Beatrice Andreucci. 2026. "From Passive Consumers to Active Citizens: A Survey-Based Study of Prosumerism in Jerusalem" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010481

APA StyleKádár, J., Pilloni, M., Cornelis, M., Bosman, L., Riveros, J. V. Z., Hamed, T. A., & Andreucci, M. B. (2026). From Passive Consumers to Active Citizens: A Survey-Based Study of Prosumerism in Jerusalem. Sustainability, 18(1), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010481