Enterprise Groups and Environmental Investment Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China’s Heavily Polluting Industries

Abstract

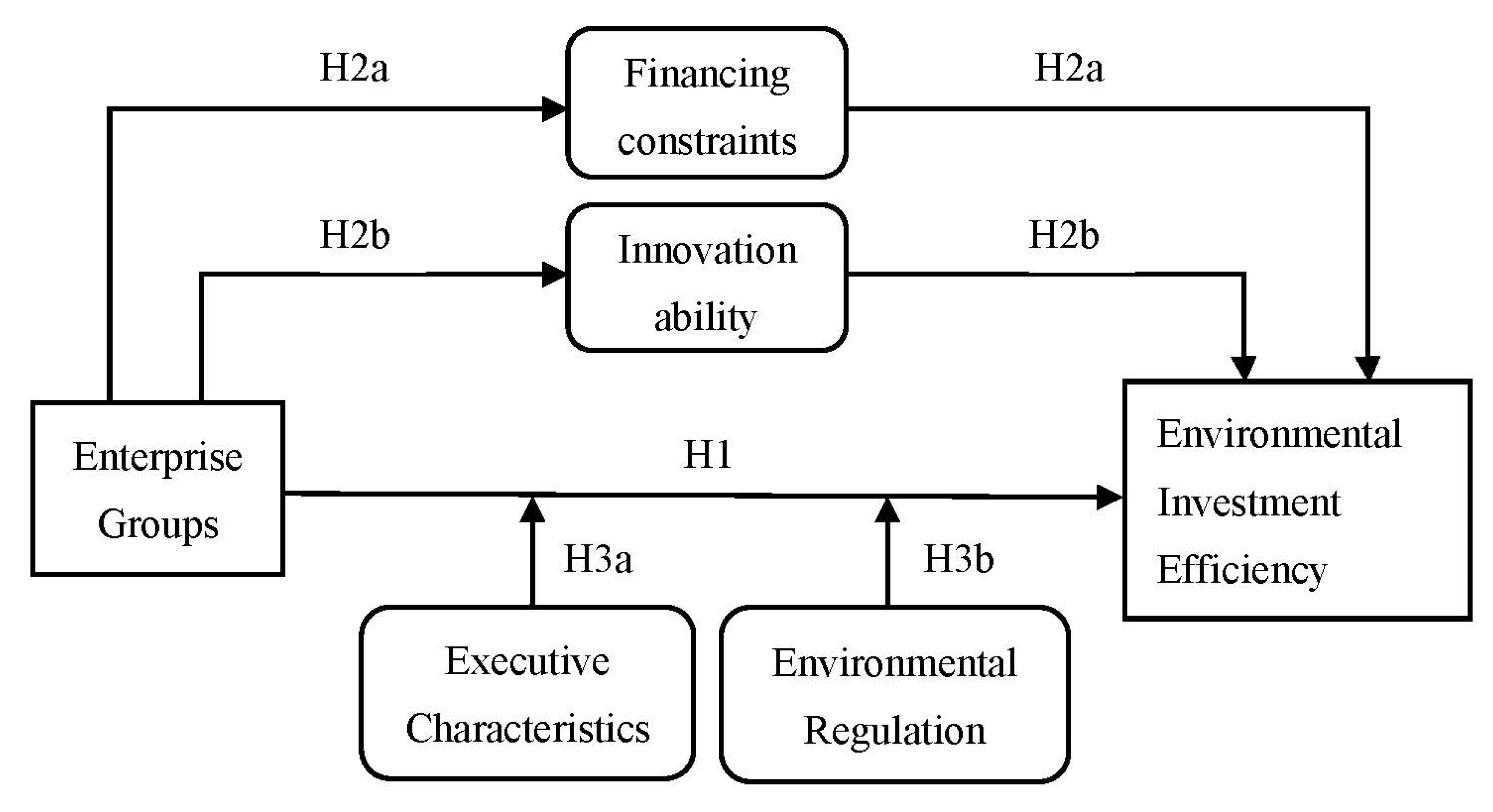

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Influence of Enterprise Groups on Environmental Investment Efficiency

2.2. Mediating Effect Analysis of Enterprise Groups on Environmental Investment Efficiency

- a.

- Technology adoption: Implementing cutting-edge pollution control systems;

- b.

- Process optimization: Enhancing resource utilization efficiency;

- c.

- R&D integration: Transforming investments into measurable environmental gains.

- Accelerated technological learning curves;

- Enhanced problem-solving capacity for environmental challenges;

- Superior adaptation to regulatory requirements.

2.2.1. Enterprise Groups, Financing Constraints, and Environmental Investment Efficiency

2.2.2. Enterprise Groups, Innovation Ability, and Environmental Investment Efficiency

2.3. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Enterprise Groups on Environmental Investment Efficiency

- a.

- Standardizing environmental practices across subsidiaries;

- b.

- Creating economies of scale in compliance technologies;

- c.

- Strengthening internal resource reallocation toward high-impact initiatives.

3. Study Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Definition

- (1)

- Quantifying corporate environmental investment efficiency presents unique methodological challenges, as it involves balancing desirable economic outputs against undesirable ecological impacts within a complex operational system. To capture this nuanced efficiency landscape, we employed the non-radial, non-oriented Slack-Based Measure Data Envelopment Analysis (SBM-DEA) model—a sophisticated approach that avoids restrictive radial or angular assumptions while accommodating intricate input-output relationships. Our implementation carefully integrates three fundamental resource inputs: total environmental protection expenditures, capital investments in fixed assets, and workforce scale measured through employee counts. For outputs, we distinguish between desirable economic returns (total operating revenue) and undesirable environmental consequences (carbon emissions footprint). This carefully calibrated framework generates comprehensive efficiency scores (denoted as Eff) that reveal how effectively organizations transform ecological investments into both economic value creation and emission control outcomes. The particular strength of this methodology lies in its ability to identify optimization potential across all dimensions simultaneously, providing a holistic view of environmental investment performance that mirrors real-world operational complexities.

- (2)

- Identification of enterprise groups. Referring to the existing research practice [40], the following method was adopted to identify enterprise groups. If two or more listed companies share the same final controller in the same year, the listed companies are subordinate to an enterprise group. Notably, if the final controller is the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), the companies will be traced back to the enterprise level that is directly subordinate to SASAC at all levels.

- (3)

- Selection of control variables. Following the practice of the existing literature [41,42,43], a series of control variables that may affect enterprises’ environmental investment efficiency were selected, including return on total assets (Roa), asset-liability ratio (Lev), enterprise scale (Size), duality (Dual), shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder (Top_1), equity balance degree (Balance), board size (Board), Tobin’s Q ratio (Q), and Herfindahl index (HHI), which are specifically defined in Table 2.

3.3. Model Setting

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Multivariate Multicollinearity Tests

4.3. Multiple Regression Results

4.4. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Endogeneity Handling: Test Based on the Reform of State-Owned Enterprises

4.4.2. Endogeneity Handling: Heckman Two-Stage Method

4.4.3. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

4.4.4. Change in the Estimation Method

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Influencing Mechanism Analysis

5.1.1. Financing Constraint Channel

5.1.2. Channels of Innovation Ability

5.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

5.2.1. Executive Characteristics

5.2.2. Environmental Regulation

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1. Nature of Property Rights

5.3.2. Geographic Area

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- A multi-stage approach to guarantee rigorous conclusions. The previous analysis is the first step that we used to quantify the efficiency of environmental investing in the form of slacks-based measure data envelopment analysis (SBM-DEA) model to create exact measures of performance during the 18-year input-output period. Next, the Least Squares Dummy Variable (LSDV) estimation confirmed that affiliation with the enterprise group results in a significant positive difference in the effectiveness of environmental investments. This underlying connection proved an extremely robust one against varied robustness tests: instrument variable strategies to overcome the issue of endogeneity, Heckman two-stage adjustments to overcome the issue of sample selection, propensity score matching to balance observable differences, and alternative methods of estimation—all together lending support to the methodological plausibility of the underlying connection.

- (2)

- In addition to the direct relationship, we were able to define the two major channels of the transmission: enterprise groups significantly reduce the financing constraints that normally affect environmental investments, and in the process, enhance innovation capabilities through the exchange of knowledge. These processes facilitate greater prioritization of funds in sustainable programs. The contextual issues were also identified in our analysis of moderation: the executive features have a significant impact on implementation efficacy, the age of leaders mitigated the group advantage, and the international experience intensified the finding. There is a positive moderating factor between this relationship, namely, environmental regulations insinuate synergistic benefits of policy frameworks on organizational advantage.

- (3)

- Significant variation emerges across ownership structures and geographical contexts. Non-state-owned enterprise groups generate substantially stronger environmental efficiency improvements than state-owned counterparts, reflecting differential governance priorities and operational flexibilities. Regionally, both eastern and western China exhibit statistically significant positive effects, though the magnitude proves considerably stronger in the economically advanced eastern region. Notably, central Chinese enterprises demonstrate no significant efficiency differential between group-affiliated and independent firms, highlighting how regional development disparities and institutional environments condition organizational effectiveness.

- (4)

- These findings collectively demonstrate that organizational design constitutes a strategic lever for enhancing environmental performance. Enterprise groups’ internal resource allocation mechanisms—spanning financial, human, and knowledge capital—create structural advantages in executing sustainability initiatives. For policymakers, our results suggest that encouraging enterprise group formation could complement regulatory approaches in advancing environmental goals. Corporate leaders should recognize organizational architecture as a sustainability enabler, particularly through developing internal capital markets and cross-firm knowledge-sharing protocols. This research fundamentally advances understanding of how structural choices influence environmental performance beyond conventional factors like regulation or ownership type.

7.2. Policy Recommendations

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, C.X.; Liu, Y.H.; Yang, X.Y.; Wang, H.X. Investment and Financing on China’s Environmental Protection Industry: Problems and Solutions. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.H.; Wang, C.X.; Dong, Z.F. Research on the Synergistic Effect of Carbon Emission Reduction of Environmental Protection Investment. Jiang-Huai Trib. 2022, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, N.; Li, Q.; Zhou, W. Environmental regulation, foreign direct investment and China’s economic development under the new normal: Restrain or promote? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 4195–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Huang, S.; Dang, C. Environmental cost control system of manufacturing enterprises using artificial intelligence based on value chain of circular economy. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2022, 16, 1856422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, S.M.; Hou, K.; Kim, S. Real effects of climate policy: Financial constraints and spillovers. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 143, 668–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaraite, J.; Kurtyka, O.; Ollivier, H. Take a ride on the green side: How do CDM projects affect Indian manufacturing firms’ environmental performance? Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2021, 37605, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Z. Can digitalization reduce industrial pollution? Roles of environmental investment and green innovation. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, B.L. Air Pollution Control Intensity and Ecological Total-factor Energy Efficiency: The Moderating Effect of Ownership Structure. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.W.F. The design of supranational organizations for the provision of international public goods: Global environmental protection. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2000, 22, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Meng, D.; Bai, G.; Song, L. Performance Pressure of Listed Companies and Environmental Information Disclosure: An Empirical Research on Chinese Enterprise Groups. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Chen, S.Y.; Cai, J.Y. Business Groups, Industrial Life Cycle and Strategic Choices. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 6, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Z. Internal capital markets and risk-taking: Evidence from China Pacific-Basin. Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101968. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.J.; Saias, M.A. Strategy follows structure! Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 1, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, A.D.J. Strategy and Structure; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, J.W. The Strategic Decision Process and Organizational Structure. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 11, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How does Green Innovation Improve Enterprises’ Competitive Advantage? The Role of Organizational Learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, V.; Pampurini, F.; Quaranta, A.G. Environmental, Social and Governance investing: Does rating matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safitri, V.A.; Sari, L.; Gamayuni, R.R. Research and Development (R&D), Environmental Investments, to Eco-Efficiency, and Firm Value. Indones. J. Account. Res. 2020, 22, 377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Dong, Y.; Lu, J. Evolutionary game analysis of coal enterprise resource integration under government regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 7127–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeppe, N.; Ariss, A.; Cooke, F.L.; Chahine, L. Talent management in German multinational firms in China: The role of headquarters-subsidiary relations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 284–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Song, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C. Does Green Finance Promote the Green Transformation of China’s Manufacturing Industry? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, R.; Jiang, H. Impact of corporate environmental responsibility on green innovation efficiency: Evidence from Chinese A-share listed companies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzari, S.M.; Athey, M.J. Asymmetric Information, Financing Constraints, and Investment. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1987, 69, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Chen, L.; Lv, Y. Equity Pledge of Venture Capital and Enterprise Innovation: An Empirical Research Based on SME Board and GEM. J. Nanjing Audit Univ. 2020, 17, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, C.Y.; Shiu, Y.M. Roles of ownership structure and investment opportunities in directing internal capital allocation within groups. Eur. J. Financ. 2025, 31, 1983–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkayastha, A.; Gupta, V.K. Business group affiliation and entrepreneurial orientation: Contingent effect of level of internationalization and firm’s performance. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2023, 40, 847–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Li, G.; Sun, P.; Peng, D. Inefficient investment and digital transformation: What is the role of financing constraints? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, R.; Malik, J.A. When Does Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Affect Investment Efficiency? A New Answer to An Old Question. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402093112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pata, U.K.; Caglar, A.E.; Kartal, M.T.; Depren, S.K. Evaluation of the role of clean energy technologies, human capital, urbanization, and income on the environmental quality in the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Chu, D.X.; Lian, Y.H.; Zheng, J. Can ESG Performance Improve Enterprise Investment Efficiency? Secur. Mark. Her. 2021, 11, 24–34+72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, M.; Gao, L. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Improve Firm Investment Efficiency? Rev. Account. Financ. 2017, 16, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.Z. Impacts of digital transformation on eco-innovation and sustainable performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.A.; Cox, C.M. The Influence of Gender on the Perception and Response to Investment Risk: The Case of Professional Investors. J. Psychol. Financ. Mark. 2001, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Sun, W.; Yang, N.; Leng, X. An executive’s environmental background and corporate environmental responsibility performance: Evidence from green investors and environmental investment. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.D.; Robert, L.B. Pollution Regulation as a Barrier to New Firm Entry: Initial Evidence and Implications for Future Research. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 288–303. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Duan, L. Can informal environmental regulation restrain air pollution?–Evidence from media environmental coverage. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, R.; Liu, R. The Impact of green finance on persistence of green innovation at firm-level:a moderating perspective based on environmental regulation intensity. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhu, B. Earnings pressure, external supervision, and corporate environmental protection investment: Comparison between heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, X.; Rui, O.; Zha, X. Business Group in China. J. Corp. Financ. 2013, 22, 166–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.L.; Ji, R. The Impact of Tax Avoidance on Enterprise Investment Efficiency. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2018, 21, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, W.; Tian, G.G.; Zhang, H.F. Corporate Pyramids, Geographical Distance, and Investment Efficiency of Chinese State-owned Enterprises. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 99, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Hou, J.N.; Li, X. Industry Policy, Cross-region Investment, and Enterprise Investment Efficiency. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 56, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Zhang, L.; Hou, T.J.; Liu, H.Y. Testing and Application of the Mediating Effects. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 5, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.X.; Ni, X.R.; Zhao, P.; Yang, T.T. The Impact of Business Groups on Innovation Outputs: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 1, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, M.; Liao, G.; Yu, X. The Brain Gain of Corporate Boards: Evidence from China. J. Financ. 2015, 70, 1629–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.H.; Joshua, R.P. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving Beyond the KZ Index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Hsu, P.H.; Li, D. Innovative Efficiency and Stock Returns. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 107, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.X. Environmental Regulation, Management’s Compensation Incentive and Corporate Environmental Investment—Evidence from the Implementation of the Environmental Protection Law in 2015. Account. Res. 2021, 403, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Zhan, J.; Xu, Y.; Zuo, A.; Lv, X. Challenges or drivers? Threshold effects of environmental regulation on China’s agricultural green productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.F.; Zhnag, Z.Y.; Jiang, G.L. Empirical Study of the Relationship between FDI and Environmental Regulation: An Intergovernmental Competition Perspective. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, F.; Wu, T.; Ren, Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Yuan, X. The impact of environmental regulation on green investment efficiency of thermal power enterprises in China-based on a three-stage exogenous variable model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.Q.; Ma, X.X.; Li, Y.D.; Tang, T. Off-site Allocation of Capital Elements and Optimization of Investment Efficiency in Enterprise Groups: Based on the New Era Situation of the Construction of a Unified National Market. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 24, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.R.M.; Luo, R.H. Financing constraints and investment efficiency: Evidence from a panel of Canadian forest firms. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 5142–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xia, B.; Chen, Y.; Ding, N.; Wang, J. Environmental uncertainty, financing constraints and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 70, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Islam, A.R.M.; Wang, R. Financing constraints and investment efficiency in Canadian real estate and construction firms: A stochastic frontier analysis. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Yao, J.L. Business Group, Diversification and Technological Innovation. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2020, 40, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, I.U.; Shahzad, F.; Laique, U.; Hanif, M.A. Does environmental innovation improve investment efficiency? Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, Y. Digital investment and environmental performance: The mediating roles of production efficiency and green innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 259, 108822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Liu, K. Foreign direct investment, environmental regulation and urban green development efficiency—An empirical study from China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Badulescu, A.; Badulescu, D. Modeling and analyzing critical policies for improving energy efficiency in manufacturing sector: An interpretive structural modeling (ISM). Energy 2025, 18, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis Code | Hypothesis Content |

|---|---|

| H1 | Compared with independently listed companies, listed companies that are subordinate to enterprise groups exhibit higher environmental investment efficiency; that is, enterprise groups have a significantly positive impact on environmental investment efficiency. |

| H2a | Enterprise groups can improve environmental investment efficiency through the mediating mechanism—financing constraints. |

| H2b | Enterprise groups can improve environmental investment efficiency through the mediating mechanism—innovation ability. |

| H3a | Executive characteristics play a moderating role between enterprise groups and environmental investment efficiency. |

| H3b | Environmental regulation plays a moderating role between enterprise groups and environmental investment efficiency. |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Symbol | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| explained variable | Environmental investment efficiency | Eff | DEA estimated value |

| core variable | Enterprise group | Group | If two or more listed companies share the same final controller in the same year, such listed companies are considered subordinate to an enterprise group. |

| mediating variable | Financing constraint | SA | The SA index is obtained by measuring |

| Innovation ability | Rd | The natural logarithm of the total number of applications for invention, utility model, and design patents plus 1 | |

| moderator variable | Average age of executives | Age | Average age of all executives of the enterprise in the year |

| Overseas backgrounds of executives | Oversea | The firm has at least one executive with overseas study or work experience in that year; if yes, the variable is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Environmental regulation | lnEI | Calculated using industrial wastewater emissions, industrial sulfur dioxide emissions, and industrial soot emissions | |

| control variables | Return on total assets | Roa | Net profit at the end of the period/average balance of total assets at the end of the period |

| Asset-liability ratio | Lev | Total indebtedness at the end of the year/total assets at the end of the year | |

| Enterprise scale | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets at the end of the period | |

| Duality | Dual | Whether the general manager and director are the same person; if yes, the variable is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder | Top_1 | Stock holding quantity of the largest shareholder/total number of stocks | |

| Equity balance degree | Balance | Total shareholding ratio of the second to fifth largest shareholders/shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder | |

| Board size | Board | Total number of members on the board of directors | |

| Tobin’s Q ratio | Q | Market value of total assets/book value of total assets | |

| Herfindahl index | HHI | Square sum of the market occupancy of all enterprises within each industry | |

| Dummy variable of industry | Industry | Dummy variable of industry | |

| Dummy variable of year | Year | Dummy variable of year | |

| Dummy variable of region | Province | Dummy variable of region |

| Panel (A): Full sample | |||||

| VARIABLES | N | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

| Eff | 7538 | 0.230 | 0.222 | 0.038 | 1 |

| Group | 7538 | 0.356 | 0.479 | 0 | 1 |

| Roa | 7538 | 0.048 | 0.049 | −0.162 | 0.203 |

| Lev | 7538 | 0.446 | 0.194 | 0.063 | 0.888 |

| Size | 7538 | 22.232 | 1.339 | 18.370 | 28.636 |

| Dual | 7538 | 0.181 | 0.385 | 0 | 1 |

| Top_1 | 7538 | 0.376 | 0.157 | 0.093 | 0.743 |

| Balance | 7538 | 0.644 | 0.601 | 0.005 | 2.961 |

| Board | 7538 | 9.125 | 1.912 | 5 | 15 |

| Q | 7538 | 1.671 | 0.875 | 0.670 | 6.139 |

| HHI | 7538 | 0.160 | 0.109 | 0.035 | 0.591 |

| Panel (B): Intragroup comparison | |||||

| VARIABLES | Group = 0 | Group = 1 | Difference | ||

| Eff | 0.215 | 0.257 | −0.042 *** | ||

| Roa | 0.052 | 0.041 | 0.011 *** | ||

| Lev | 0.413 | 0.506 | −0.092 *** | ||

| Size | 21.872 | 22.882 | −1.010 *** | ||

| Dual | 0.244 | 0.067 | 0.178 *** | ||

| Top_1 | 0.348 | 0.426 | −0.078 *** | ||

| Balance | 0.746 | 0.459 | 0.287 *** | ||

| Board | 8.849 | 9.624 | −0.775 *** | ||

| Q | 1.738 | 1.551 | 0.186 *** | ||

| HHI | 0.154 | 0.173 | −0.019 *** | ||

| VARIABLES | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Group | 1.26 | 0.791 |

| Roa | 1.32 | 0.759 |

| Lev | 1.58 | 0.634 |

| Size | 1.62 | 0.617 |

| Dual | 1.08 | 0.925 |

| Top_1 | 2.19 | 0.457 |

| Balance | 2.10 | 0.476 |

| Board | 1.14 | 0.875 |

| Q | 1.28 | 0.784 |

| HHI | 1.04 | 0.966 |

| Mean VIF | 1.46 |

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eff | Eff | Eff | |

| Group | 0.042 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.035 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Roa | −0.764 *** | −0.807 *** | |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | ||

| Lev | 0.155 *** | 0.113 *** | |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | ||

| Size | −0.022 *** | −0.004 | |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | ||

| Dual | −0.008 | −0.012 * | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Top_1 | 0.168 *** | 0.141 *** | |

| (0.023) | (0.024) | ||

| Balance | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | ||

| Board | 0.003 ** | 0.001 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Q | 0.006 * | 0.006 * | |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | ||

| HHI | 0.219 *** | 0.198 *** | |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | ||

| Constant | 0.215 *** | 0.541 *** | 0.165 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.050) | (0.063) | |

| Year | N | N | Y |

| Industry | N | N | Y |

| Province | N | N | Y |

| Observations | 7538 | 7538 | 7538 |

| R-squared | 0.008 | 0.089 | 0.162 |

| VARIABLES | (1) Instrumental Variable First Stage | (2) Instrumental Variable Second Stage | (3) Heckman Second Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Eff | Eff | |

| Group | 0.039 *** | 0.032 *** | |

| (0.011) | (0.006) | ||

| Policy * Firmage | 0.038 *** | ||

| (0.000) | |||

| Policy * State | 0.004 *** | ||

| (0.000) | |||

| Roa | −0.017 | −0.805 *** | −0.780 *** |

| (0.053) | (0.083) | (0.059) | |

| Lev | −0.037 ** | 0.114 *** | 0.112 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.030) | (0.016) | |

| Size | 0.004 * | −0.005 | −0.007 ** |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | |

| Dual | −0.005 | −0.012 | −0.005 |

| (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| Top_1 | 0.070 *** | 0.140 *** | 0.141 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.050) | (0.024) | |

| Balance | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.011 * |

| (0.005) | (0.011) | (0.006) | |

| Board | 0.004 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | |

| Q | 0.006 * | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| HHI | 0.001 | 0.198 *** | 0.196 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.059) | (0.023) | |

| Imr | −0.015 * | ||

| (0.009) | |||

| Constant | 0.168 *** | 0.171 | 0.260 *** |

| (0.059) | (0.116) | (0.083) | |

| Year | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry | Y | Y | Y |

| Province | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 7538 | 7538 | 7538 |

| R-squared | 0.846 | 0.162 | 0.162 |

| F-test of excluded instruments | 3319.82 *** |

| VARIABLES | PSM | Tobit |

|---|---|---|

| Eff | Eff | |

| Group | 0.035 *** | 0.037 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Controls | Y | Y |

| Year | Y | Y |

| Industry | Y | Y |

| Province | Y | Y |

| Constant | 0.140 ** | 0.169 *** |

| (0.063) | (0.065) | |

| Observations | 7454 | 7538 |

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eff | SA | Eff | Rd | Eff | |

| Group | 0.035 *** | −0.038 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.019 ** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.055) | (0.003) | |

| SA | −0.045 *** | ||||

| (0.012) | |||||

| Rd | 0.003 * | ||||

| (0.001) | |||||

| Roa | −0.807 *** | −0.141 ** | −0.813 *** | 0.639 | −0.735 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.055) | (0.057) | (0.531) | (0.069) | |

| Lev | 0.113 *** | −0.197 *** | 0.105 *** | −1.201 *** | 0.176 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.151) | (0.020) | |

| Size | −0.004 | 1.217 *** | 0.050 *** | 0.278 *** | −0.015 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.027) | (0.003) | |

| Dual | −0.012 * | 0.047 *** | −0.010 | 0.258 *** | −0.008 |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.052) | (0.007) | |

| Top_1 | 0.141 *** | 0.590 *** | 0.167 *** | 0.000 | 0.095 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.025) | (0.201) | (0.027) | |

| Balance | 0.006 | 0.113 *** | 0.011 * | −0.211 * | −0.008 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.097) | (0.013) | |

| Board | 0.001 | 0.003 * | 0.001 | 0.034 * | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.014) | (0.002) | |

| Q | 0.006 * | 0.014 *** | 0.007 * | 0.038 | 0.011 ** |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.026) | (0.004) | |

| HHI | 0.198 *** | −0.162 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.349 | 0.094 ** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.260) | (0.030) | |

| Constant | 0.165 *** | −22.407 *** | −0.836 *** | −4.213 *** | 0.447 *** |

| (0.063) | (0.060) | (0.276) | (0.571) | (0.062) | |

| Year | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Province | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 7538 | 7538 | 7538 | 5504 | 5504 |

| R-squared | 0.162 | 0.985 | 0.163 | 0.048 | 0.077 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Eff | Eff | Eff |

| Group | 0.154 ** | 0.045 *** | 0.050 *** |

| (0.066) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Group * Age | −0.002 * | ||

| (0.001) | |||

| Group * Oversea | 0.072 * | ||

| (0.037) | |||

| Group * lnEI | −0.018 ** | ||

| (0.007) | |||

| Roa | −0.810 *** | −0.808 *** | −0.810 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.057) | |

| Lev | 0.113 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.112 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| Size | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.005 * |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Dual | −0.013 * | −0.012 * | −0.012 * |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Top_1 | 0.140 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.137 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | |

| Balance | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Board | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Q | 0.006 * | 0.006 * | 0.005 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| HHI | 0.200 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.199 *** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | |

| Constant | 0.167 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.161 ** |

| (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.063) | |

| Observations | 7538 | 7538 | 7514 |

| R-squared | 0.162 | 0.162 | 0.163 |

| VARIABLES | Nature of Property Rights | Geographic Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Non-State-Owned Enterprises | State-Owned Enterprises | Western Region | Central Region | Eastern Region | |

| Group | 0.049 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.026 ** | 0.012 | 0.051 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.008) | |

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Province | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | 0.477 *** | −0.052 | −0.223 | −0.092 | 0.425 *** |

| (0.102) | (0.086) | (0.143) | (0.128) | (0.082) | |

| Observations | 3608 | 3930 | 1255 | 1912 | 4371 |

| R-squared | 0.170 | 0.196 | 0.215 | 0.213 | 0.148 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, S.; Tian, T.; Jiang, W.; Xing, K.; Wang, Q.; Feng, X. Enterprise Groups and Environmental Investment Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China’s Heavily Polluting Industries. Sustainability 2026, 18, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010480

Zhao S, Tian T, Jiang W, Xing K, Wang Q, Feng X. Enterprise Groups and Environmental Investment Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China’s Heavily Polluting Industries. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010480

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Siya, Tao Tian, Wei Jiang, Kai Xing, Qing Wang, and Xumeng Feng. 2026. "Enterprise Groups and Environmental Investment Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China’s Heavily Polluting Industries" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010480

APA StyleZhao, S., Tian, T., Jiang, W., Xing, K., Wang, Q., & Feng, X. (2026). Enterprise Groups and Environmental Investment Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China’s Heavily Polluting Industries. Sustainability, 18(1), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010480