On Recovery Opportunity for Critical Elements from Effluent Water from Mining, Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Operations in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Characterization of Water Effluents

3.1. Coal Mines

3.2. Abandoned Coal Mines

3.3. Lignite Mines

3.4. Copper Mines

3.5. Chemical Raw Material Mines

3.6. Oil and Gas Fields

3.7. Geothermal and Curative Water

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- La Rivière, J.W.M. Threats to the World’s water. Sci. Am. 1989, 261, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasechko, S.; Seybold, H.; Perrone, D.; Fan, Y.; Shamsudduha, M.; Taylor, R.G.; Fallatah, O.; Kirchner, J.W. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 2024, 625, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailiušis, B.; Kriaučiūnenė, J.; Jakimavičius, D.; Šarauskienė, D. The variability of long-term run-off series in the Baltic Sea drainage basin. Baltica 2011, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak-Wójcicka, K.; Machula, S. Influence of climate changes on the state of water resources in Poland and their usage. Geosciences 2020, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Office, Environment, Statistical Information and Elaboration. Ochrona Środowiska 2016; Central Statistical Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 163–164. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2016,1,17.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Szwed, M.; Karg, G.; Pinskwar, I.; Radziejewski, M.; Graczyk, D.; Kedziora, A.; Kundzewicz, Z.W. Climate change and its effect on agriculture, water resources and human health sectors in Poland. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.M.; Bednorz, E. Atlas of Climate in Poland (1991–2020); Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2022; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10593/26990 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Schrijvers, D.; Hool, A.; Blengini, G.A.; Chen, W.-Q.; Dewulf, J.; Eggert, R.; van Ellen, L.; Gauss, R.; Goddin, J.; Habib, K.; et al. A review of methods and data to determine raw material criticality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieć, M.; Galos, K.; Szamałek, K. Main challenges of mineral resources policy of poland. Resour. Policy 2014, 42, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, E.; Guzik, K.; Galos, K. On the Possibilities of critical raw materials production from the EU’s primary sources. Resources 2021, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S. Challenges, opportunities, and technological advances in desalination brine mining: A mini review. Adv. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mends, E.A.; Chu, P. Lithium extraction from unconventional aqueous resources—A review on recent technological development for seawater and geothermal brines. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xevgenos, D.; Panteleaki Tourkodimitri, K.; Mortou, M.; Mitko, K.; Sapoutzi, D.; Stroutza, D.; Turek, M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. The concept of circular water value and its role in the design and implementation of circular desalination projects. The case of coal mines in Poland. Desalination 2024, 579, 117501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelatontsev, D.; Mukhachev, A.; Shevchenko, V. Comprehensive utilization of mineral resources in produced water from oil and gas industry—A critical review. Desalination 2026, 619, 119558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, D. The general methods of mine water treatment in China. Desal. Water Treat. 2020, 202, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombert, P.; Sracek, O.; Koukouzas, N.; Gzyl, G.; Valladares, S.T.; Frączek, R.; Klinger, C.; Bauerek, A.; Areces, J.E.Á.; Chamberlain, S.; et al. An overview of priority pollutants in selected coal mine discharges in Europe. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalidis, G.A.; Tourkodimitri, K.P.; Mitko, K.; Gzyl, G.; Skalny, A.; Posada, J.A.; Xevgenos, D. Assessing the environmental performance of a novel coal mine brine treatment technique: A case in Poland. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitko, K.; Dydo, P.; Milewski, A.K.; Bok-Badura, J.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A.; Krawczyk, T.; Cieplok, A.; Krodkiewska, M.; Spyra, A.; Gzyl, G.; et al. Mine wastewater effect on the aquatic diversity and the ecological status of the watercourses in Southern Poland. Water 2024, 16, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razowska-Jaworek, L.; Pasternak, M.; Karpiński, I.M.; Będkowski, Z.; Kaczorowski, Z.; Wysocka, I.; Drzewicz, P.; Sokołowski, K.; Konieczyńska, M. Wstępna ocena możliwości pozyskiwania metali i pierwiastków z wód podziemnych (Preliminary feasibility assessment of recovering of valuable metals and elements from various groundwater sources). In Raport Końcowy Realizacji Zadania w Ramach “Wsparcia Działań Głównego Geologa Kraju w Zakresie Prowadzenia Polityki Surowcowej Państwa”; A Project Report; National Geological Archive (Narodowe Archiwum Geologiczne): Warsaw, Poland, 2020. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Wysocka, I.; Vassileva, E. Method validation for high resolution sector field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry determination of the emerging contaminants in the open ocean: Rare Earth Elements as a case study. Spectrochim. Acta B 2017, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, I.; Kaczor-Kurzawa, D.; Porowski, A. Development and Validation of seaFAST-ICP-QMS Method for determination of Rare Earth Elements total concentrations in natural mineral waters. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 133008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczor-Kurzawa, D.; Wysocka, I.; Porowski, A.; Drzewicz, P. The occurrence and distribution of rare earth elements in mineral and thermal waters in the Polish Lowlands. J. Geochem. Explor. 2022, 237, 106984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlauer-Łukaszewska, A.; Ławicki, Ł.; Engel, J.; Drewniak, E.; Ciężak, K.; Marchowski, D. Quantifying a mass mortality event in freshwater wildlife within the Lower Odra River: Insights from a large European river. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Kappler, A. Desorption of arsenic from clay and humic acid-coated clay by dissolved phosphate and silicate. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2011, 126, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski-Vähälä, J.; Hartikainen, H.; Tallberg, P. Phosphorus mobilization from various sediment pools in response to increased pH and silicate concentration. J. Environ. Qual. 2001, 30, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Czapowski, G. Salt domes in Poland—Potential sites for hydrogen storage in caverns. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 21414–21427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Przybycin, A. Present and future status of the underground space use in Poland. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Sener, S.E.; Thomas, V.M.; Hogan, D.E.; Maier, R.M.; Carbajales-Dale, M.; Barton, M.D.; Karanfil, T.; Crittenden, J.C.; Amy, G.L. Recovery of critical metals from aqueous sources. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 11616–11634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredkin, M.; Zabolotsky, A.; Jeffress, G. In situ recovery, an alternative to conventional methods of mining: Exploration, resource estimation, environmental issues, project evaluation and economics. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 79, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Chanois, R.M.; Cooper, N.J.; Lee, B.; Patel, S.K.; Mazurowski, L.; Graedel, T.E.; Elimelech, M. Prospects of metal recovery from wastewater and brine. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy-water-environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, I.C.; Soldatos, P.G. Water desalination cost literature: Review and assessment. Desalination 2008, 223, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria-Díaz, J.J.; López-Méndez, M.C.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.P.; Sandoval-Herazo, L.C.; Correa-Mahecha, F. Commercial thermal technologies for desalination of water from renewable energies: A State of the Art Review. Processes 2021, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, C.M.; Al Hamzah, A.A.; East, C.P. Scale control in thermal desalination. In Water-Formed Deposits; Amjad, Z., Demadis, K.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, N.M. A Review of Scale control Methods. Desalination 1979, 31, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraldy, E.; Rahmawati, F.; Heriyanto Putra, D.P. Preparation of struvite from desalination waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S.K.; Suraparaju, S.K.; Elavarasan, R.M. A Review on low-temperature thermal desalination approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 32443–32466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Bu, L.; Guerra-Valle, M.; Petzold, G.; Orellana-Palma, P. Technical and environmental opportunities for freeze Desalination. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2023, 52, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janajreh, I.; Zhang, H.; El Kadi, K.; Ghaffour, N. Freeze desalination: Current research development and future prospects. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekanayake, U.G.M.; Seo, D.H.; Faershteyn, K.; O’Mullane, A.P.; Shon, H.; MacLeod, J.; Golberg, D.; Ostrikov, K. Atmospheric-pressure plasma seawater desalination: Clean energy, agriculture, and resource recovery nexus for a blue planet. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2020, 25, e00181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzke, M.; Rumbach, P.; Go, D.B.; Sankaran, R.M. Evidence for the electrolysis of water by atmospheric-pressure plasmas formed at the surface of aqueous solutions. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2012, 45, 442001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, U.M.; Rathilal, S.; Isa, Y.M. Membrane desalination technologies in water treatment: A review. Water Pract. Technol. 2018, 13, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minier-Matar, J.; Hussain, A.; Janson, A.; Benyahia, F.; Adham, S. Field evaluation of membrane distillation technologies for desalination of highly saline brines. Desalination 2014, 351, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane distillation: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhu, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xue, L. Development of lower cost seawater desalination processes using nanofiltration technologies—A review. Desalination 2015, 376, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenten, I.G.; Khoiruddin. Reverse osmosis applications: Prospect and challenges. Desalination 2016, 391, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathmann, H. Electrodialysis, a mature technology with a multitude of new applications. Desalination 2010, 264, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, A.; Gurreri, L.; Ciofalo, M.; Micale, G.; Tamburini, A.; Cipollina, A. Electrodialysis for water desalination: A critical assessment of recent developments on process fundamentals, models, and applications. Desalination 2018, 434, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Sabur, G.M.; Akter, M.M.; Nam, S.Y.; Im, K.S.; Tijing, L.; Shon, H.K. Electrodialysis desalination, resource, and energy recovery from water industries for a circular economy. Desalination 2024, 569, 117041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidar, M.; Fateev, V.; Bouzek, K. Membrane electrolysis—History, current status and perspective. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 209, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, I.K.; Lee, C.H. Techno-economic and environmental evaluation of CO2 mineralization technology based on bench-scale experiments. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, T.; Tleimat, B.W.; Klein, G. Ion-exchange pretreatment for scale prevention in desalting systems. Desalination 1983, 47, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Brighu, U.; Jain, S.; Meena, A. Hybrid configurations for brackish water desalination: A review of operational parameters and their impact on performance. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2023, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowska, A.; Gajda, D.K.; Kiegiel, K.; Miśkiewicz, A.; Drzewicz, P.; Zakrzewska-Kołtuniewicz, G. Purification of flowback fluids after hydraulic fracturing of Polish gas shales by hybrid methods. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

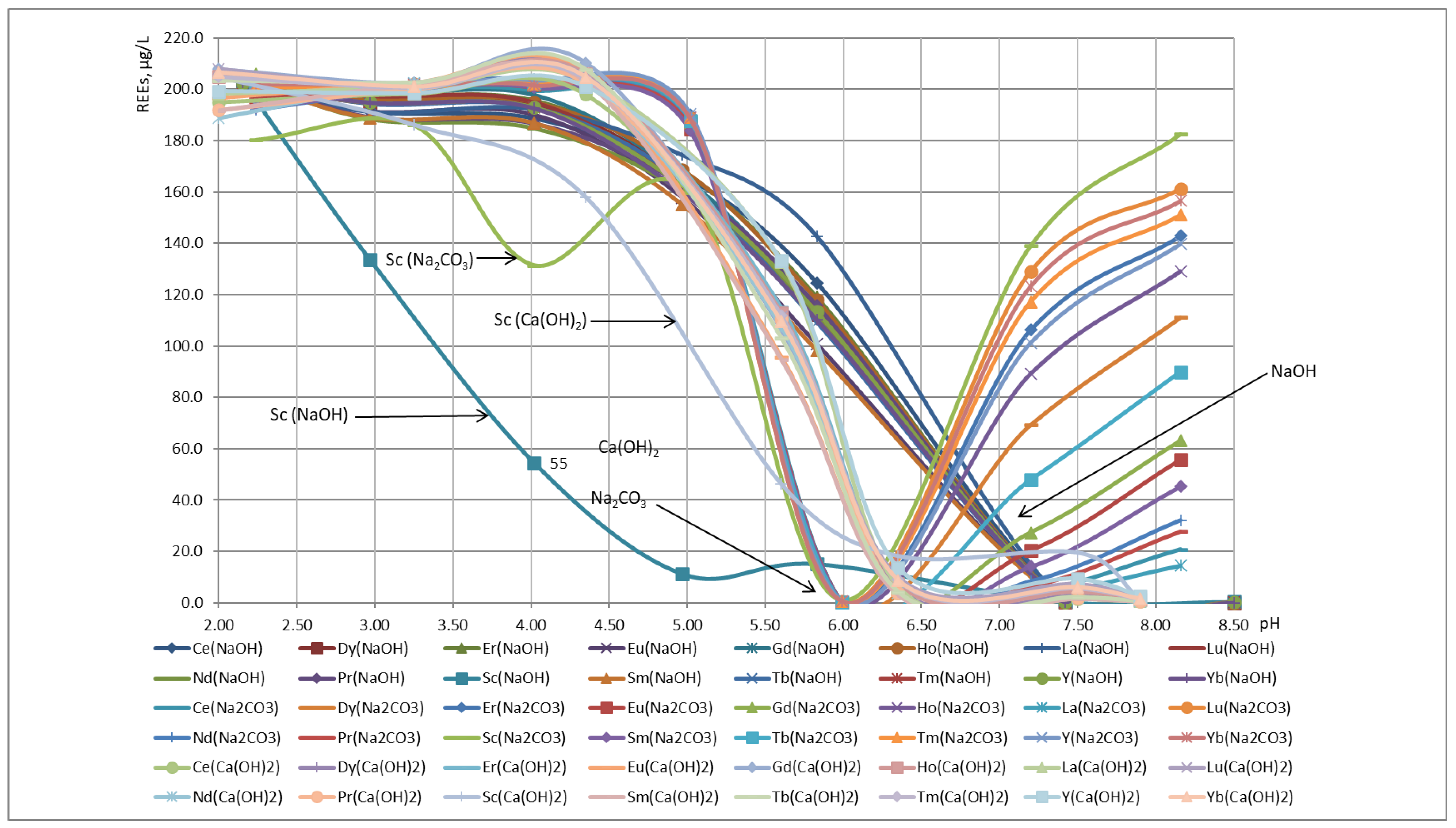

- Thomas, M.; Białecka, B.; Cykowska, M.; Bebek, M.; Bauerek, A. Precipitation of Rare Earth Elements from model and real solutions by using alkaline and sulfur compounds. Przem. Chem. 2017, 96, 2471–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, P.K.; Santana, M.V.E.; Hokanson, D.R.; Mihelcic, J.R.; Zhang, Q. Carbon footprint of water reuse and desalination: A review of greenhouse gas emissions and estimation tools. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 2014, 4, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Valipour, M.; Choo, K.-H.; Ahmed, A.T.; Baba, A.; Kumar, R.; Toor, G.S.; Wang, Z. Desalination: From ancient to present and future. Water 2021, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah, I.; Mustafa, J.; Zafar, A.M.; Obaid, M.; Atieh, M.A.; Ghaffour, N. Waste to wealth: A critical analysis of resource recovery from desalination brine. Desalination 2022, 543, 116093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavukkandy, M.O.; Chabib, C.M.; Mustafa, I.; Al Ghaferi, A.; Al Marzooqi, F. Brine management in desalination industry: From waste to resources generation. Desalination 2019, 472, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, A.; Jacangelo, J.G. Emerging Desalination technologies for water treatment: A critical review. Water Res. 2015, 75, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Dessouky, H.T.; Ettouney, H.M. Fundamentals of Salt Water Desalination; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naas, M.H.; Mohammad, A.F.; Suleiman, M.I.; Al Musharfy, M.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H. A New process for the capture of CO2 and reduction of water salinity. Desalination 2017, 411, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, J.; Mourad, A.A.-H.I.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; El-Naas, M.H. Simultaneous treatment of reject brine and capture of carbon dioxide: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2020, 483, 114386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, P.; Naidu, G.; Vigneswaran, S. Mining valuable minerals from seawater: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2017, 3, 7–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, S.; Vicari, F.; López, J.; Salem, M.; Lo Brutto, R.; Azzouz, S.; Chamam, S.; Cataldo, S.; Muratore, N.; de Labastida, M.F.; et al. Unlocking hidden mineral resources: Characterization and potential of bitterns as alternative sources of critical raw materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.; He, L.; Zhao, Z. Facet engineered Li3PO4 for lithium recovery from brines. Desalination 2021, 514, 115186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Naidu, G.; Fukuda, H.; Du, F.; Vigneswaran, S.; Drioli, E.; Lienhard, J.H.V. Metals recovery from seawater desalination brines: Technologies, opportunities, and challenges. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 7704–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, B. Recovery and recycling of lithium: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 172, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkh, B.A.; Al-Amoudi, A.A.; Farooque, M.; Fellows, C.M.; Ihm, S.; Lee, S.; Li, S.; Voutchkov, N. Seawater desalination concentrate—A new frontier for sustainable mining of valuable minerals. npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Jho, E.H.; Park, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H. Potassium recovery from potassium solution and seawater using different adsorbents. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.G.; Seckler, M.; Rocha, S.D.F.; Saturnino, D.; de Oliveira, É.D. Thermodynamic modelling of phases equilibrium in aqueous systems to recover potassium chloride from natural brines. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2017, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelich, C.J.; Williams, M.D.; Rahardianto, A.; Franklin, J.C.; Cohen, Y. High-recovery reverse osmosis desalination using intermediate chemical demineralization. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 301, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giwa, A.; Dufour, V.; Al Marzooqi, F.; Al Kaabi, M.; Hasan, S.W. Brine management methods: Recent innovations and current status. Desalination 2017, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Phillips, K.R.; Thiel, G.P.; Schröder, U.; Lienhard, J.H. Direct electrosynthesis of sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid from brine streams. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Site Number | Location | Description | Strata | Amount of Discharged Water in 2019 [m3/year] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Silesian Coal Basin | ||||

| 1 | Coal mine “Janina 1” | Level 500 m | Carboniferous | 3,679,200 |

| 2 | Coal mine “Janina 2” | Level 800 m | Carboniferous | 525,600 |

| 3 | Coal mine “Sobieski” | Dam of water reservoir | Carboniferous | 788,400 |

| 4 | Coal mine “Dębieńsko 1” | Level 600 m | Carboniferous | 1,219,392 |

| 5 | Coal mine “Dębieńsko 2” | Level 690 m | Carboniferous | 173,448 |

| 6 | Coal mine “Rydułtowy-Anna” | Level 800 m | Carboniferous | 2,628,000 |

| 7 | Coal mine “Ruda Ruch Halemba” | Level 1030 m | Carboniferous | 2,628,000 |

| 8 | Coal mine “Śląsk” | Level 1030 m | Carboniferous | 420,480 |

| 9 | Coal mine “Knurów-Szczygłowice” | Mainshaft “Paweł” | Carboniferous | 326,923 |

| 10 | Coal mine “Krupiński” | Level 620 m | Carboniferous | 157,680 |

| 11 | Coal mine “Budryk” | Desalination plant “Dębieńsko” | Carboniferous | 872,496 |

| 12 | Coal mine “ROW Ruch Marcel” | Cut-through C-14. Level 800 | Carboniferous | 157,680 |

| 13 | Coal mine “Piast-Ziemowit” | Level 650 m | Carboniferous | 140,400 |

| 14 | Mine drainage collector reservoir “Olza” | Mine drainage collector reservoir “Olza” | Carboniferous | 7,358,400 |

| 15 | Coal mine Jastrzębie-Bzie. Ruch Jastrzębie | Level 600 m | Carboniferous | 52,560 |

| 16 | Coal mine Murcki-Staszic 1 | Level 720 m | Carboniferous | 168,192 |

| 17 | Coal mine Murcki-Staszic 2 | Level 821 m | Carboniferous | |

| 18 | Coal mine ROW Jankowice | Mine water drainage collector | Carboniferous | 2,628,000 |

| 19 | Desalination plant “Dębieńsko 1” | Mine water drainage collector | Carboniferous | 1,752,000 |

| 20 | Desalination plant “Dębieńsko 2” | Concentrated brine discharge to settling ponds | Carboniferous | 1,839,600 |

| Abandoned mines | ||||

| 21 | Coal mine “Niwka Modrzejów” | Mineshaft “Sosnowiec” | Carboniferous | 5,273,216 |

| 22 | Coal mine “Saturn” | Mineshaft “Paweł”, Czeladź | Carboniferous | 13,144,073 |

| 23 | Coal mine. “Katowice” | Mineshaft near Mine Museum | Carboniferous | 2,273,309 |

| 24 | Coal mine “Kleofas” | Mineshaft “Kleofas”, Katowice | Carboniferous | 2,274,128 |

| 25 | Coal mine “Gliwice” | 2nd Mineshaft | Carboniferous | 2,288,577 |

| 26 | Coal mine “Pstrowski” | Mineshaft “Pstrowski Zabrze” | Carboniferous | 7,952,295 |

| 27 | Coal mine “Powstańców Śląskich” | City of Radzionków | Carboniferous | 1,431,588 |

| 28 | Coal mine “Szombierki” | Discharge to mine water drainage “Bytom” | Carboniferous | 3,417,670 |

| 29 | Coal mine “Siemianowice” | Mineshaft “Kolejowy I” | Carboniferous | 7,230,324 |

| Lower Silesian Coal Basin | ||||

| 30 | Closed coal mine Nowa Ruda | Drainage “Nowa Ruda” | Carboniferous | 525,600 |

| Lublin Coal Basin | ||||

| 31 | Coal mine “Lubelski Węgiel “Bogdanka 1” | Level 720 m | Jurassic | 3,679,200 |

| 32 | Coal mine “Lubelski Węgiel “Bogdanka 2” | Level 960 m | Jurassic-Carboniferous | 1,576,800 |

| Geothermal and curative water | ||||

| 33 | Kazimierskie Wody Lecznicze i Termalne (spa) | Well “Cudzynowice GT-1” | Cretaceous | 913 |

| 34 | Uzdrowisko Cieplice (spa) | Well “C-1” | Cretaceous | 146,000 |

| 35 | Park Wodny Bania S.A. (aquapark) | Well “GT-1” (at Białka Tatrzańska) | Neogene-Triassic | 247,153 |

| 36 | Geotermia Podhalańska S.A. (geothermal plant) | Well “Bańska PGP-1” | Neogene-Triassic | 2,451,671 |

| 37 | Geotermia Mazowiecka S.A (geothermal plant) | Well “Mszczonów IG-1” | Cretaceous | 297,840 |

| 38 | MILEX Sp. z o.o. | Well “Trzęsacz GT-1” | Jurassic | 395,714 |

| 39 | Tarnowska Gospodarka Komunalna | Well “Tarnowo Podgórne GT-1” | Jurassic | 36 |

| 40 | Uzdrowisko Kamień Pomorski (spa) | Well “Edward III” | Jurassic | 4284 |

| 41 | Przedsiębiorstwo Uzdrowiskowe Ustroń S.A. (spa) | Well “U-3 (IG-3)” | Devon | 4113 |

| 42 | Geotermia Pyrzyce Sp. z o.o. (geothermal plant) | Well “ Pyrzyce GT-1 Bis” | Jurassic | 1,052,244 |

| 43 | G-Term Energy Sp. z o.o. (geothermal plant) | Well “Stargard Szczeciński GT-2” | Jurassic | 1,678,400 |

| Lignite deposits | ||||

| 44 | Open-cast lignite mine “Adamów” | Mine drainage | Neogene | 525,600 |

| 45 | Open-cast lignite mine “Konin” | Mine drainage collector reservoir | Neogene | 18,688,000 |

| 46 | Open-cast lignite mine “Turów” | Mine drainage | Neogene | 870,000 |

| 47 | Open-cast lignite mine “Bełchatów” | Mine drainage at Rogowiec | Neogene | 15,768,000 |

| Deposits of chemical raw materials | ||||

| 48 | Gypsum mine “Leszcze S.A.” | Sump | Miocene | 82,125 |

| 49 | Gypsum mine “Nowy Ląd” | Sump | Permian | 706,572 |

| 50 | Sulfur mine “Siarkopol” Osiek | Mine water collecting pipeline | Neogene | 2,007,500 |

| 51 | Sulfur mine Basznia II | Mine water collecting pipeline | Neogene | 394,200 |

| 52 | Salt mine “Góra” | Reservoir “Solino” | Permian | 4,467,600 |

| 53 | Salt mine Kłodawa S.A. | Level 750 m | Permian | 365 |

| 54 | Iodine-Bromine brine processing plant “Salco S.J.” | Well “Siedlec S-5” | Permian | 2992 |

| Copper ore deposits | ||||

| 55 | Mine “Lubin 1” | Mineshaft “LIII” | Permian | 9,288,190 |

| 56 | Mine “Lubin 2” | Mineshaft “LI” | Permian | |

| 57 | Mine “Polkowice-Sieroszowice” | Pit water drainage | Permian | 12,410,784 |

| 58 | Mine “Rudna” | Well “TO-75” | Permian | 5,487,401 |

| Natural gas deposits | ||||

| 59 | Pilzno, Subcarpathia | Borehole “Pilzno 48” | Neogene | 1095 |

| 60 | Tarnów, Subcarpathia | Borhole “Tarnów 81k” | Neogene | 5475 |

| 61 | Żuchlów | Borehole “Żuchlów-11” | Permian | 50 |

| 62 | Bogdaj-Uciechów | Borehole “Bogdaj Uciechów-11” | Permian | 8925 |

| 63 | Wilków 1 | Produced water reservoir | Permian | 91 |

| 64 | Cierpisz | Borehole 3d | Neogene | 2737 |

| 65 | Kuryłówka | Borehole 5 | Neogene | 5475 |

| 66 | Terliczka | Borehole 3cg | Neogene | 5475 |

| 67 | Wilków 2 | Borehole 37 | Permian | 90.75 |

| Location | The Most Prospective Source | Amount of Discharged Water in 2019, m3/year | TDS, mg/L | Critical Elements at Pumping Rate in 2019, t/year | Critical Elements at the Highest Allowed Pumping Rate, t/year | The Total Concentration of Critical Elements, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Silesian Coal Basin | ||||||

| 1 | Coal mine “Janina 1” | 3,679,200 | 94,322 | 4061 | 3535 | |

| 3 | Coal mine “Sobieski” | 788,400 | 38,229 | 938 | 1608 | |

| 7 | Coal mine “Ruda Ruch Halemba” | 2,628,000 | 12,805 | 776 | 399 | |

| 8 | Coal mine “Śląsk” | 420,480 | 38,198 | 331 | 1088 | |

| 11 | Coal mine “Budryk” | 872,496 | 81,286 | 1197 | 1890 | |

| 14 | Mine drainage collector reservoir “Olza” | 7,358,400 | 24,024 | 3175 | 585 | |

| 18 | Coal mine ROW Jankowice | 2,628,000 | 42,139 | 1317 | 1074 | |

| 20 | Desalination plant “Dębieńsko 2” | 1,839,600 | 312,963 | 50,554 | 26,623 | |

| Abandoned mines | ||||||

| 22 | Coal mine “Saturn” | 13,144,073 | 1396 | 999 | 86 | |

| 25 | Coal mine “Gliwice” | 2,288,577 | 13,676 | 499 | 289 | |

| 26 | Coal mine “Pstrowski” | 7,952,295 | 7638 | 1274 | 211 | |

| 29 | Coal mine “Siemianowice” | 7,230,324 | 6009 | 1035 | 187 | |

| Geothermal and curative water | ||||||

| 33 | Kazimierskie Wody Lecznicze i Termalne (spa) | 913 | 12,161 | 0.01 | 192 | 333 |

| 34 | Uzdrowisko Cieplice (spa) | 146,000 | 635 | 12 | 9918 | 6 |

| 36 | Geotermia Podhalańska “Bańska” | 2 516 | 292 | 1118 | 101 | |

| 38 | MILEX Sp. z o.o. | 395,714 | 10,169 | 25 | 99 | 70 |

| 40 | Uzdrowisko Kamień Pomorski | 32,037 | 1 | 64 | 365 | |

| 41 | Przedsiębiorstwo Uzdrowiskowe Ustroń S.A. (spa) | 4113 | 90,767 | 10 | 505 | 3191 |

| 42 | Geotermia Pyrzyce Sp. z o.o. (geothermal plant) | 1,052,244 | 117,371 | 885 | 2504 | 1116 |

| 43 | G-Term Energy Sp. z o.o. (geothermal plant) | 1,678,400 | 120,753 | 1465 | 3057 | 1143 |

| Salt mines | ||||||

| 52 | Salt mine “Góra” | 4,467,600 | 324,315 | 5926 | 1828 | |

| 53 | Salt mine Kłodawa S.A. | 365 | 463,567 | 23 | 15,514 | 86,202 |

| 54 | Iodine-Bromine brine processing plant “Salco S.J.” | 2992 | 184,389 | 5 | 2746 | 2358 |

| Copper ore mines | ||||||

| 55 | Mine “Lubin 1” | 9,288,190 | 6139 | 963 | 163 | |

| 57 | Mine “Polkowice-Sieroszowice” | 12,410,784 | 36,920 | 2636 | 284 | |

| 58 | Mine “Rudna” | 5,487,401 | 178,041 | 6205 | 1550 | |

| Natural gas extracting wells | ||||||

| 59 | Pilzno, Subcarpathia | 1095 | 176,758 | 2 | 103 | 2721 |

| 60 | Tarnów, Subcarpathia | 5475 | 196,879 | 11 | 387 | 2582 |

| 62 | Bogdaj-Uciechów | 8925 | 287,305 | 42 | 213 | 6316 |

| Desalination Processes | TDS Range, mg/L |

|---|---|

| Reverse osmosis | 150–70,000 |

| Evaporation | 25,000–100,000 |

| Electrodialysis | 400–500 |

| Ion exchange | 100–500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drzewicz, P.; Razowska-Jaworek, L.; Wysocka, I.A.; Pasternak, M.; Thomas, M. On Recovery Opportunity for Critical Elements from Effluent Water from Mining, Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Operations in Poland. Sustainability 2026, 18, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010047

Drzewicz P, Razowska-Jaworek L, Wysocka IA, Pasternak M, Thomas M. On Recovery Opportunity for Critical Elements from Effluent Water from Mining, Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Operations in Poland. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrzewicz, Przemysław, Lidia Razowska-Jaworek, Irena Agnieszka Wysocka, Marcin Pasternak, and Maciej Thomas. 2026. "On Recovery Opportunity for Critical Elements from Effluent Water from Mining, Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Operations in Poland" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010047

APA StyleDrzewicz, P., Razowska-Jaworek, L., Wysocka, I. A., Pasternak, M., & Thomas, M. (2026). On Recovery Opportunity for Critical Elements from Effluent Water from Mining, Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Operations in Poland. Sustainability, 18(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010047