Multi-Scale Retention to Improve Urban Stormwater Drainage Capacity Based on a Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

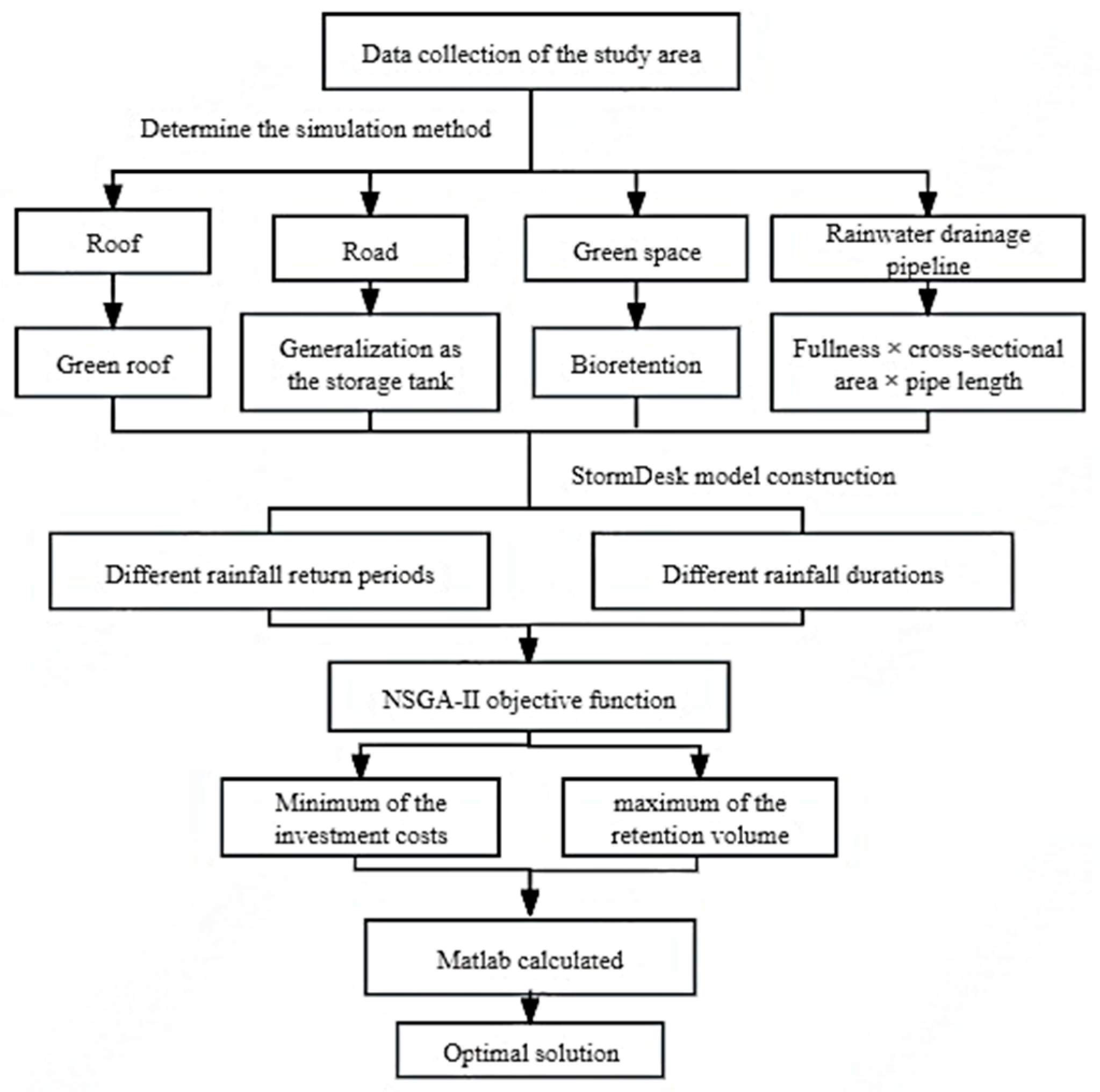

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Urban Stormwater Drainage System Enhancement Program

2.3. Stormwater Drainage Modeling Construction

2.3.1. One-Dimensional Stormater Drainage Pipeline Modeling

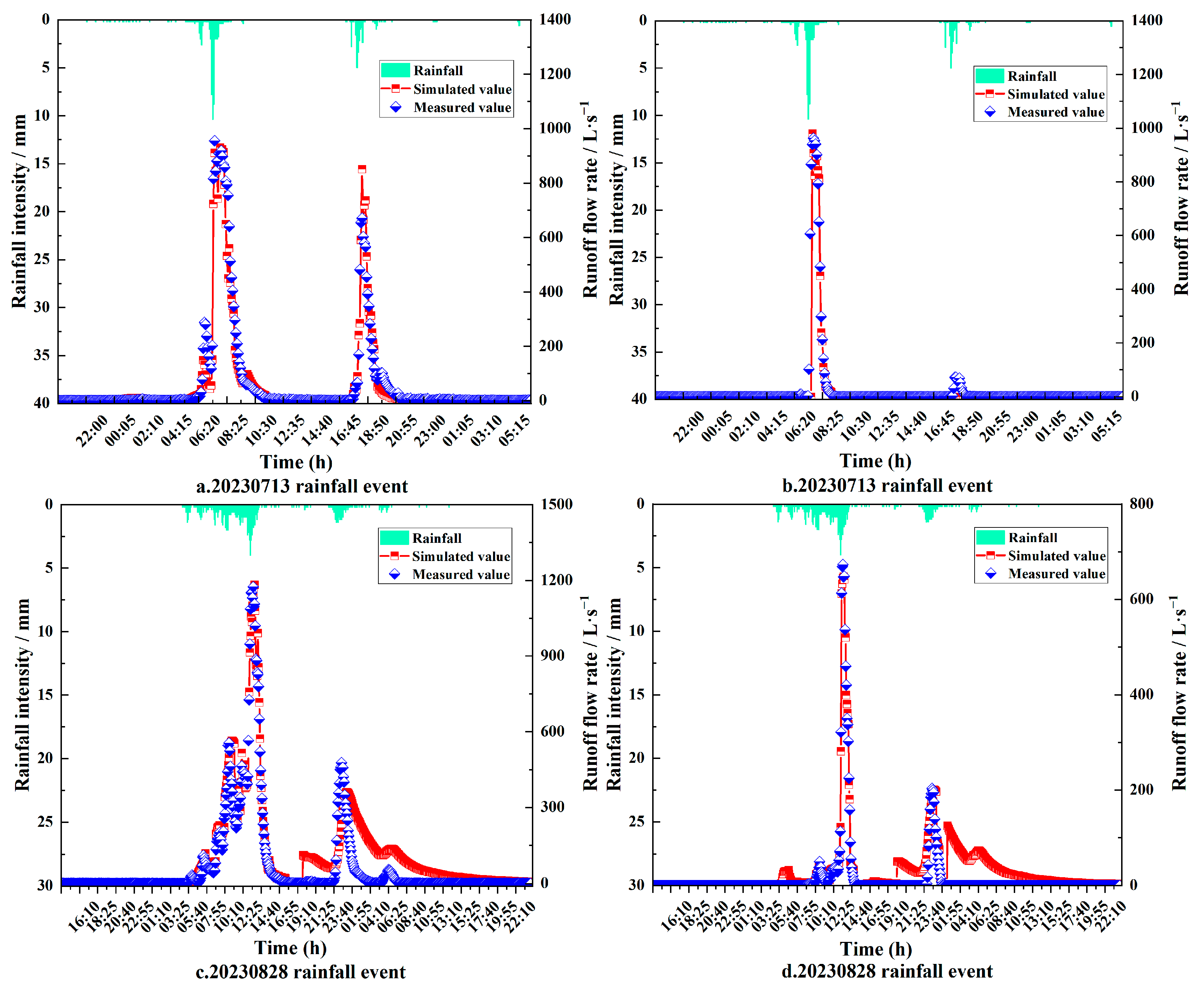

2.3.2. Parameters Calibration

- qobs,t measured overflow flow rate, L/s;

- qsim,t simulated overflow flow rate, L/s;

- qave,o average measured overflow flow rate, L/s;

- qave,s average simulated overflow flow rate, L/s.

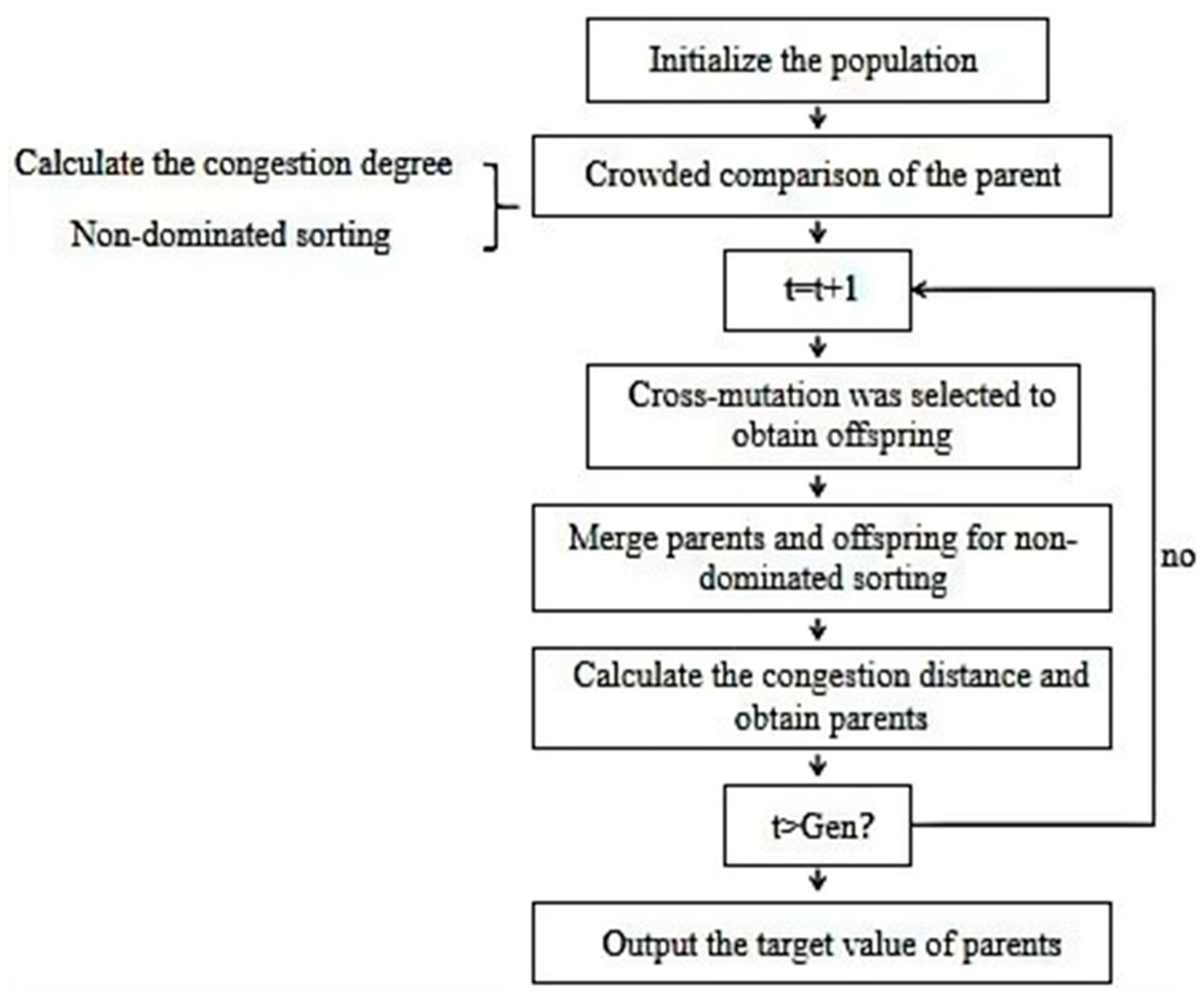

2.4. Optimization Strategy of Different Scenarios

- W the total volume of retention, m3;

- C the total construction cost, USD;

- Si for the unit retention volume, m3

- Ui the construction cost of individual retention facilities, USD;

- ϕ the retention control ratio, ranging from 40% to 100%;

- Ai the area of the i-th retention unit facility, m2;

- fi the depth of retention for the i-th retention unit, m;

- u the construction cost per unit of retention volume

- L the total green roof construction volume, m3;

- T the total volume of the road retention tank, m3;

- S the total volume of greenfield bioretention, m3;

2.5. Data Analysis Methods

- η elimination ratio, %;

- Nc the initial value of the overflow point or overflow volume (m3);

- Ni the treated value of the overflow point or overflow volume (m3);

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Calibration

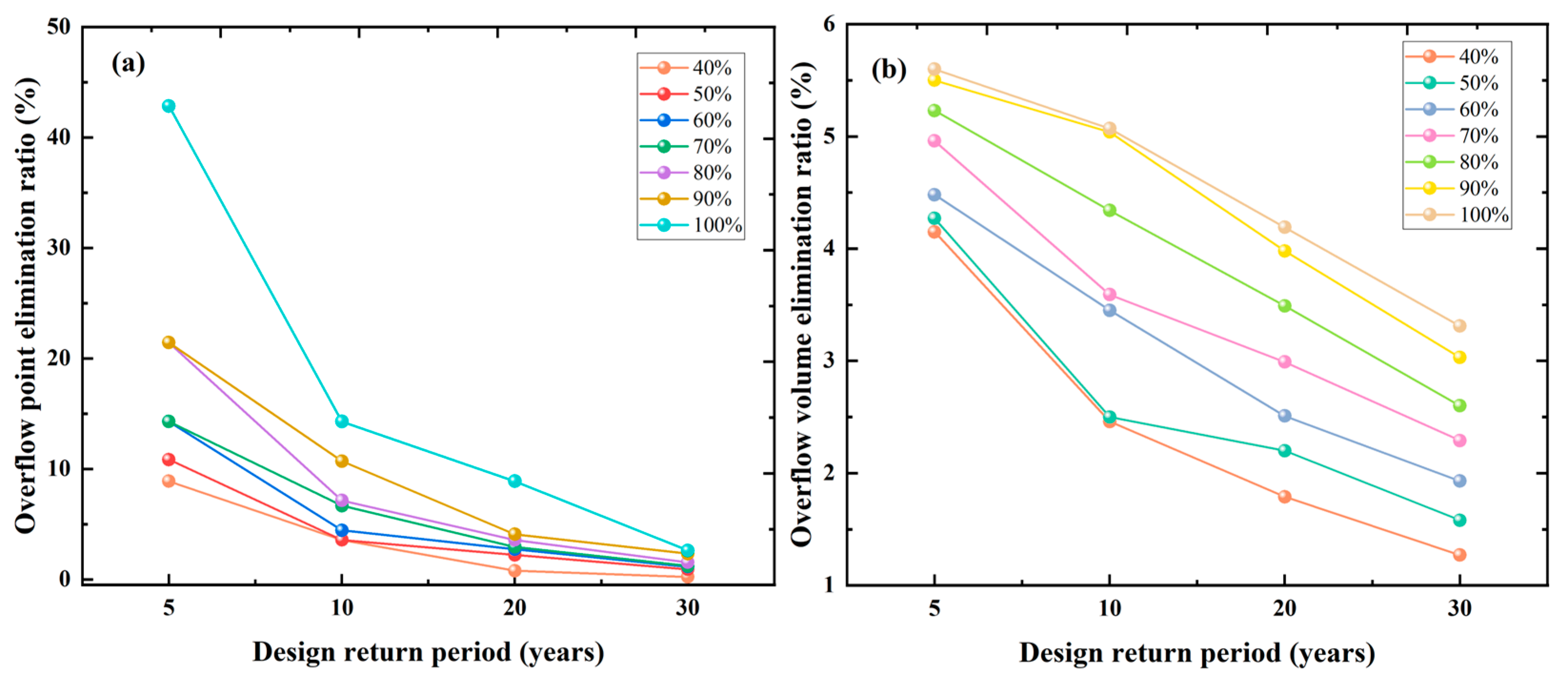

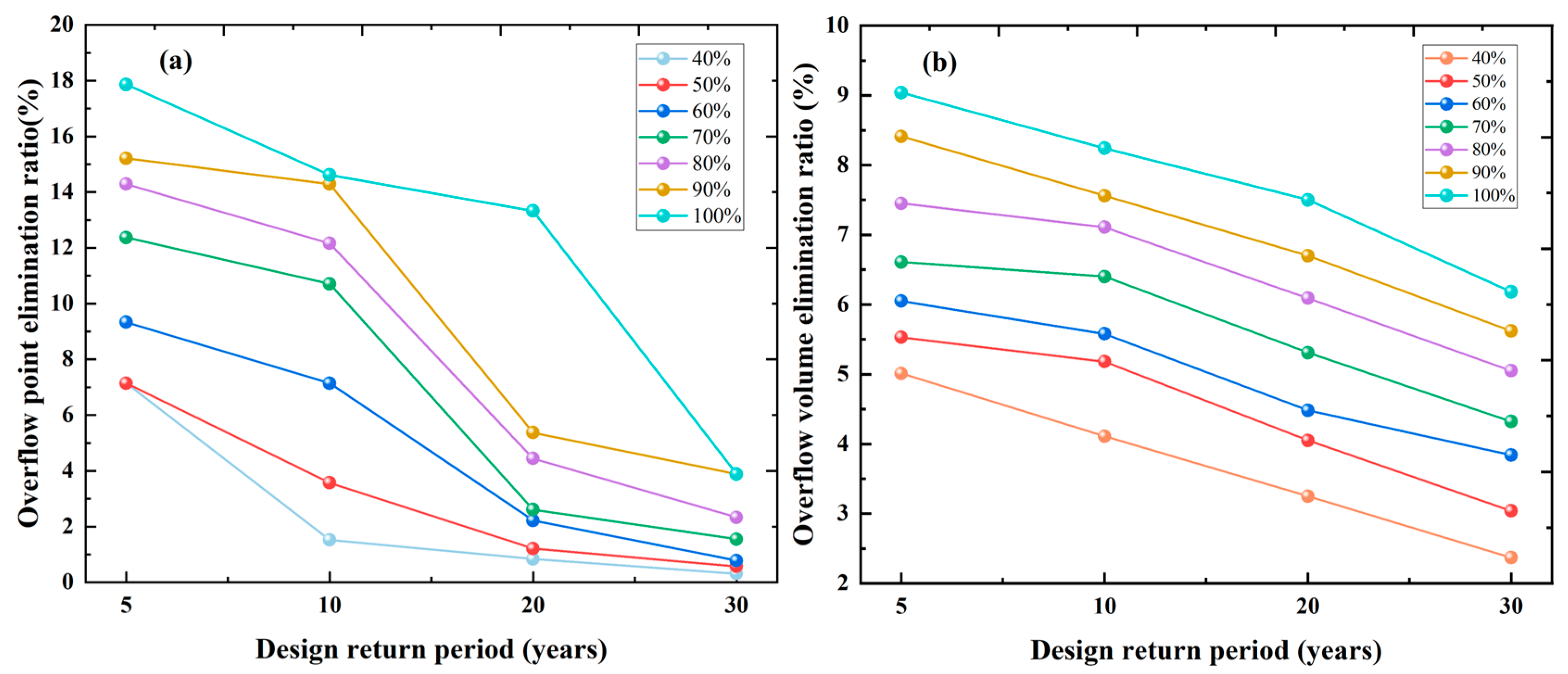

3.2. Drainage Capacity Improved Under Different Retention Ways

3.2.1. Roof Retention

3.2.2. Road Retention

3.2.3. Green Space Retention

3.2.4. Drainage Pipeline Retention

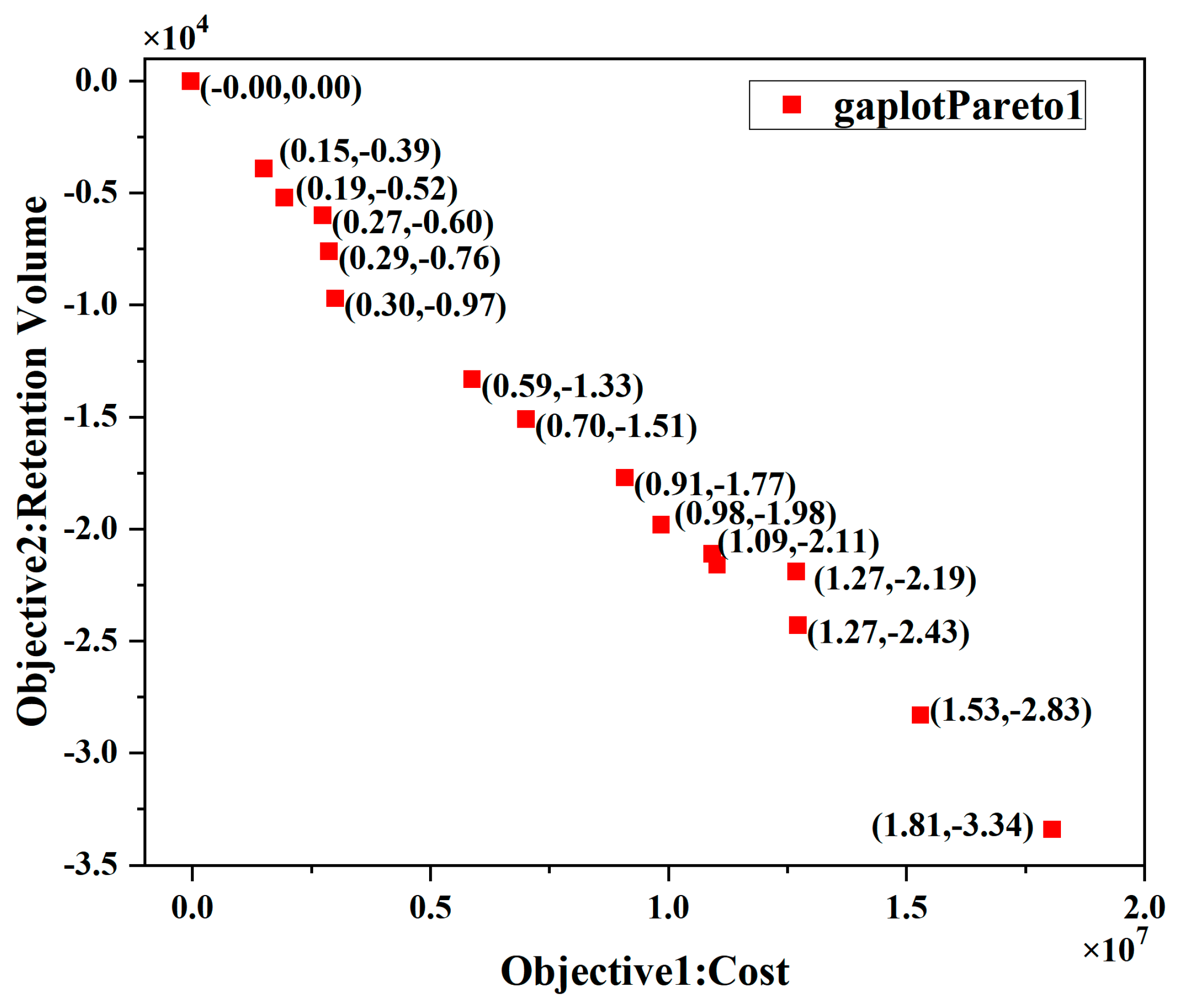

3.3. Optimization of Different Retention Scenarios

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Wu, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.; Li, G. Research on Runoff Management of Sponge Cities under Urban Expansion. Water 2024, 16, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; He, D.; Dong, Z.; Cheng, Y. Storage Scale Assessment of a Low-Impact Development System in a Sponge City. Water 2024, 16, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datola, G. Implementing urban resilience in urban planning: A comprehensive framework for urban resilience evaluation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Ge, Y.; Rott, E.; Isgandar, H. Urban resilience: Multidimensional perspectives, challenges and prospects for future research. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliardi, I.; Rovella, N.; Apollaro, C.; Bloise, A.; De Rosa, R.; Scarciglia, F.; Buttafuoco, G. Modelling seasonal variations of natural radioactivity in soils: A case study in southern Italy. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 125, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, M.T.O.V. Assessment of Urban Resilience to Floods: A Spatial Planning Framework for Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, S.H.; Wahab, A.K.A.; Shahid, S.; Asaduzzaman; Dewan, A. Low impact development techniques to mitigate the impacts of climate-change-induced urban floods: Current trends, issues and challenges. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lawluvy, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P.-S. Low Impact Development (LID) Practices: A Review on Recent Developments, Challenges and Prospects. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Fang, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Mu, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, P.; Zainol, M.R.R.M.A.; Zawawi, M.H.; Chong, K.L.; et al. Optimizing the deployment of LID facilities on a campus-scale and assessing the benefits of comprehensive control in Sponge City. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Lin, R.; Wei, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Shangguan, H.; Song, Y. Effects of low impact development on the stormwater runoff and pollution control. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Xia, J. A multi-objective optimization and evaluation framework for LID facilities considering urban surface runoff and shallow groundwater regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Qin, L.; Xue, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M. A city-scale fully controlled system for stormwater management: Consideration of flooding, non-point source pollution and sewer overflow pollution. J. Hydrol. 2021, 630 Pt D, 127155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Xu, Z. Monitoring and Evaluating Rainfall–Runoff Control Effects of a Low Impact Development System in Future Science Park of Beijing. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2021, 57, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.; Liberalesso, T.; Silva, C.M.; Sousa, V. Combining green roofs and rainwater harvesting systems in university buildings under different climate conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 163719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota-Maharaj, K.; Karunanayake, C.; Kunwar, K.; Chadee, A.A.; Azamathulla, H.M.; Rathnayake, U. Evaluation of Permeable Pavement Systems (PPS) as Best Management Practices for Stormwater Runoff Control: A Review. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2024, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, B.; Che, S. Design and Evaluation of Green Space In Situ Rainwater Regulation and Storage Systems for Combating Extreme Rainfall Events: Design of Shanghai Gongkang Green Space to Adapt to Climate Change. Land 2022, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liu, P.; Cheng, L.; Liu, W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, C. Optimization of in-pipe storage capacity use in urban drainage systems with improved DP considering the time lag of flow routing. Water Res. 2022, 227, 119350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wei, Y.; Sebastian, F.S.M.; Wang, M. Urban waterlogging control: A novel method to urban drainage pipes reconstruction, systematic and automated. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 137950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansar, H.; Duan, H.-F.; Mark, O. A multi-objective decision-making framework for implementing green-grey infrastructures to enhance urban drainage system resilience. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, D.; De Paola, F.; Ascione, G.; Giugni, M. Drainage Systems Optimization Under Climate Change Scenarios. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 2465–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Liu, T.; Shan, Y. A comprehensive survey on NSGA-II for multi-objective optimization and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 15217–15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, Y. Optimization design and research of simulation system for urban green ecological rainwater by genetic algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 11318–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Feng, P.; Miao, Y. Optimal designs of LID based on LID experiments and SWMM for a small-scale community in Tianjin, north China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 334, 117442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jato-Espino, D.; Toro-Huertas, E.I.; Güereca, L.P. Lifecycle sustainability assessment for the comparison of traditional and sustainable drainage systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ariaratnam, S.T. Life cycle cost savings analysis on traditional drainage systems from low impact development strategies. Front. Eng. Manag. 2021, 8, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, J.-L.; Wang, M.-Y.; Che, W.; Li, J. Method and feasibility analysisof blue roofs for urban stormwater runoff regulation. J. China Water Wastewater 2014, 30, 149–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, J.-L.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Wang, X.; Qiu, R. Discussion on pathways for capacity upgrading of stormwater drainage and flooding alleviation in developedurban areas based on SWMM. Environ. Eng. 2022, 40, 199–207. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.X.; Li, C.M. Effect of Different Factors on the “Net” Effect of Permeable Pavement Based on StormDe. Water Resour. Power 2024, 42, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, K.; Qiu, R.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. Effect of different MIT rainfall event division methods on volume capture ratio of annual rainfall based on bioretention assessment. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Q.; Engel, B.A.; Zhang, X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of extensive green roofs for urban stormwater control in response to future climate change scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 856, 159127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z. Increasing water retention capacity via Grey roof to green roof transformation. Water Environ. J. 2022, 36, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Wang, J.L.; Tu, N.N.; Xi, G.; Zhao, M.; Yang, B. Pilot study on runoff intercept rate of porous belt beside the urban road with large longitudinal slope. Environ. Eng. 2020, 38, 154–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, W.; Zhao, R. Emergency Response to Urban Flooding: An Assessment of Mitigation Performance and Cost-Effectiveness in Sponge City Construction. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 1993–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Lin, G.; Huang, G. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of Green Infrastructure in climate change scenarios using TOPSIS. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Davitt-Liu, I.; Erickson, A.J.; Feng, X. Integrating the Spatial Configurations of Green and Gray Infrastructure in Urban Stormwater Networks. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2023WR034796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiolo, M.; Palermo, S.A.; Brusco, A.C.; Pirouz, B.; Turco, M.; Vinci, A.; Spezzano, G.; Piro, P. On the Use of a Real-Time Control Approach for Urban Stormwater Management. Water 2020, 12, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Retention | Simulation Mode | Retention Size (S) | Retention Volume (W) | Unit Construction Cost (u) | Total Construction Cost (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roof | Green roof | (0.4–1.0) × S | A × (0.05–0.20) | 13.93–41.79 | 27.86 × S |

| Road | Generalized as the storage tank | (0.4–1.0) × S | A × (0.05–0.20) | / | 385.6 × W 0.773 |

| Green space | Bioretention | (0.4–1.0) × S | A × (0.1–0.5) | 20.89–111.44 | 90.54 × S |

| Drainage pipeline | Design fullness × cross-sectional area × pipe length | (0.4–1.0) × S × L | A × Dr | 41.79–278.6 | 222.88 × L |

| Retention Type | Total Area (m2) | Retention Depth (m) | Percentage of Retention Area (%) | Design Return Period (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roof retention | 42,093.00 | / | 40/50/60/70 /80/90/100 | 5/10/20/30 |

| Road retention | 18,694.42 | 0.05/0.10/0.15/0.20 | ||

| Green space retention | 82,000.00 | / | ||

| Drainage pipeline retention | 1631.58 |

| Serial Number | Parameters Type | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Design return period | 5 |

| 2 | Ground water collection time | 10 |

| 3 | Runoff coefficient | 0.766 |

| 4 | Centralized flow | 0 |

| 5 | Roughness factor | 0.013 |

| 6 | Floor elevation | DEM |

| 7 | Calculation method | area method |

| 8 | Minimum Overburden Depth | 1.5 |

| 9 | Minimum Pipe Diameter | 300 |

| Stormwater Drainage Pipeline Diameter (mm) | Slope (%) | Flow Rate (m3/s) |

|---|---|---|

| 300 | 3.0 | 0.0530 |

| 400 | 2.5 | 0.1041 |

| 600 | 1.5 | 0.2378 |

| 800 | 1.2 | 0.4581 |

| 1000 | 1.2 | 0.8305 |

| 1200 | 1.0 | 1.2329 |

| 1350 | 1.0 | 1.6878 |

| 1500 | 0.8 | 1.9994 |

| 1650 | 0.8 | 2.5780 |

| 1800 | 0.6 | 2.8156 |

| 2000 | 0.6 | 3.7290 |

| 2200 | 0.6 | 4.8081 |

| 2400 | 0.6 | 6.0638 |

| 2700 | 0.6 | 8.3014 |

| 3000 | 0.6 | 10.9944 |

| 3500 | 0.6 | 16.5843 |

| Program | Adaptation Scheme | Overflow Reduction Ratio Scheme | Maximum Area Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Road retention volume (m3) | 1907.3 | 1661.6 | 3738.9 |

| Roof retention volume(m3) | 741.5 | 1870.6 | 8418.6 |

| Green space retention (m3) | 1408.5 | 8199.2 | 24,600.0 |

| Construction cost ($) | 277,337.9 | 912,571.1 | 2,619,542.1 |

| Overflow elimination (m3) | 4320.0 | 6048.0 | 9430.0 |

| Unit control cost ($/m3) | 64.2 | 150.9 | 277.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Qin, H. Multi-Scale Retention to Improve Urban Stormwater Drainage Capacity Based on a Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy. Sustainability 2026, 18, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010048

Wang M, Wang J, Wang P, Qin H. Multi-Scale Retention to Improve Urban Stormwater Drainage Capacity Based on a Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Meiqi, Jianlong Wang, Peng Wang, and Haochen Qin. 2026. "Multi-Scale Retention to Improve Urban Stormwater Drainage Capacity Based on a Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010048

APA StyleWang, M., Wang, J., Wang, P., & Qin, H. (2026). Multi-Scale Retention to Improve Urban Stormwater Drainage Capacity Based on a Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy. Sustainability, 18(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010048