Deep-Sea Dilemmas: Evaluation of Public Perceptions of Deep-Sea Mineral Mining and Future of Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Survey Design

2.3. Designing of the Choice Experiment

2.4. Analytical Framework

2.4.1. Conditional Logit Model

2.4.2. WTP for Attributes

2.4.3. Random Parameter Logit Model

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Public Awareness and Perceived Impacts of Deep Seabed Mining

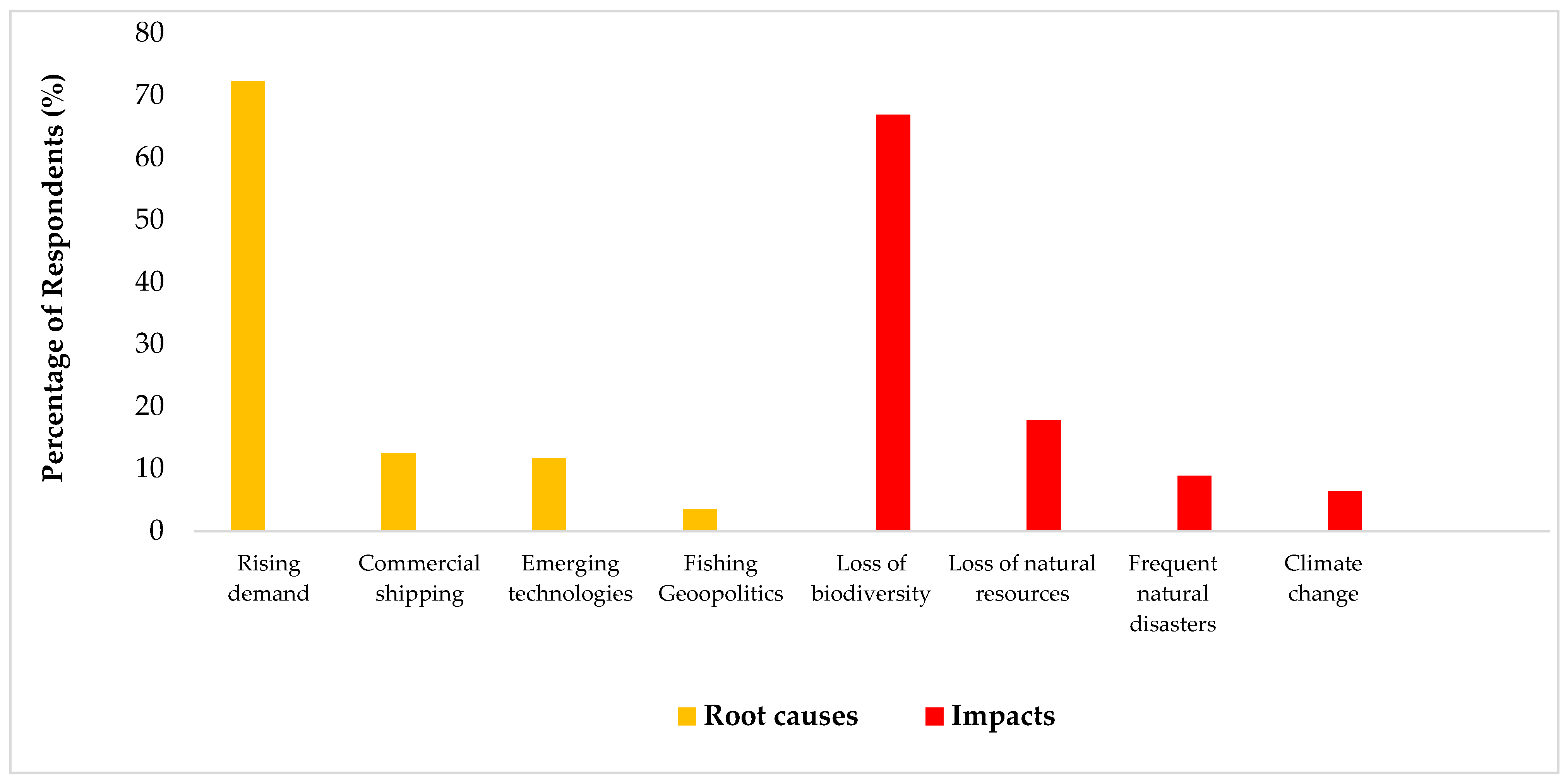

3.3. Root Causes of and Harmful Impacts of Deep-Sea Mining

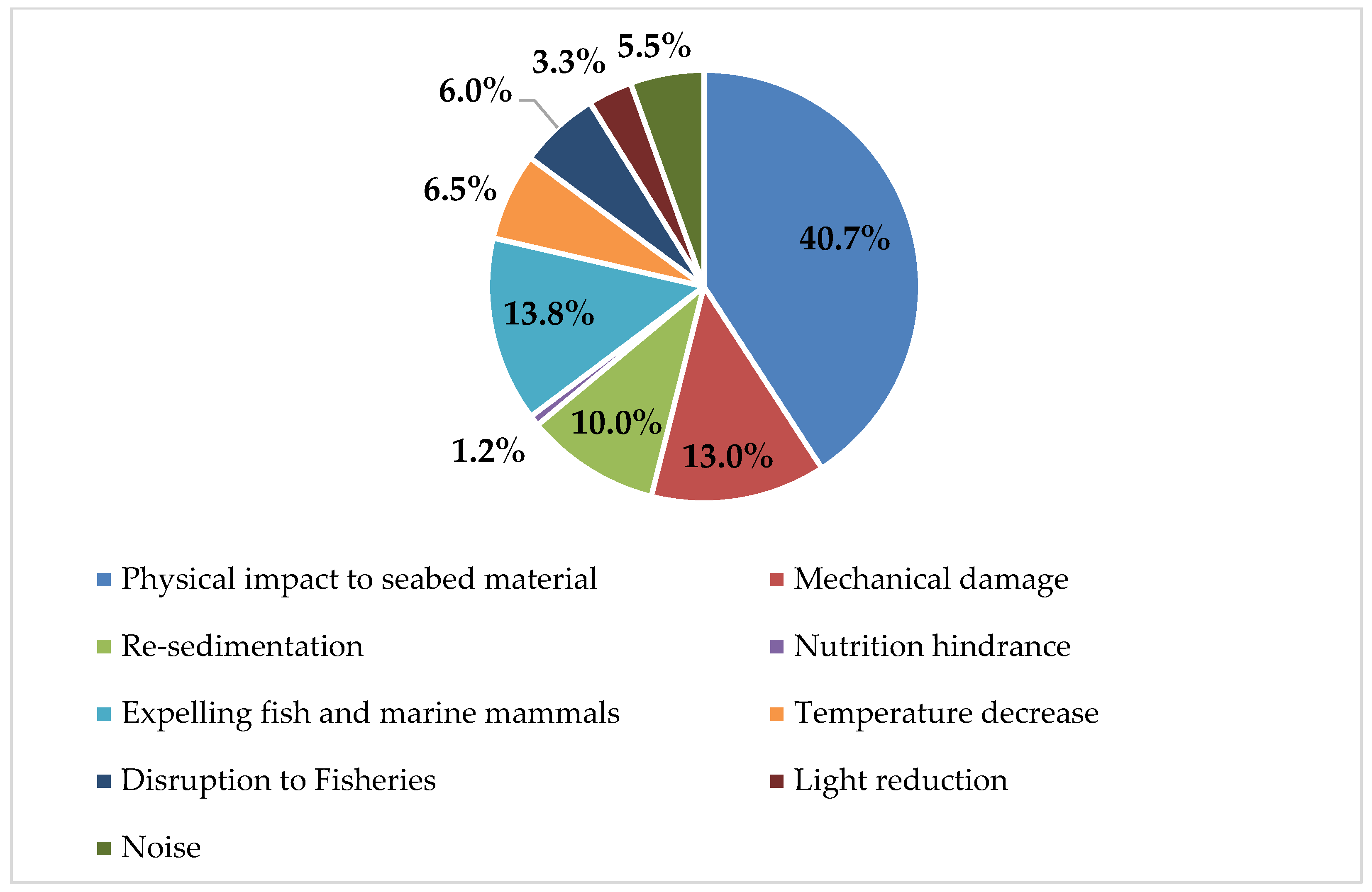

3.4. Challenges Caused by Deep Seabed Mining

3.5. Perceptions of the Ecosystem Services Provided by Coastal Ecosystems

3.6. Parameter Estimation of the Choice Experiment Using CL and RPL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUVs | Autonomous Underwater Vehicles |

| BMPs | Best Management Practices |

| CCZ | Clarion–Clipperton Zone |

| Coeff./r | Coefficient |

| CL | Conditional Logit Model |

| DCE | Discrete Choice Experiment |

| EIAs | Environmental Impact Assessments |

| EEZ | Exclusive Economic Zone |

| IIA | Irrelevant Alternatives |

| MPAs | Marine Protected Areas |

| NBSAP | National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plan |

| RPL | Random Parameter Logit |

| SE | Standard deviation |

| LKR | Sri Lankan Rupees |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| WTP | Willingness to Pay |

References

- The World Bank. World Bank Staff. The World Bank Annual Report 2007; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/732761468779449524 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Pauli, G.A. The blue economy: 10 years, 100 innovations, 100 million jobs. In The Blue Economy Series; Paradigm Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R. Deep-sea mining: Economic, technical, technological, and environmental considerations for sustainable development. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2011, 45, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, N.; Robles, P.; Jeldres, R.I. Seabed mineral resources, an alternative for the future of renewable energy: A critical review. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 126, 103699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vysetti, B. Deep-sea mineral deposits as a future source of critical metals, and environmental issues-A brief review. Miner. Miner. Mater. 2023, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Luan, L.; Sha, F.; Liu, X. Technology and equipment of deep-sea mining: State of the art and perspectives. Earth Energy Sci. 2015, 1, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson, S.Á.; Burgos, J.M.; Kutti, T.; van den Beld, I.; Egilsdóttir, H.; Arnaud-Haond, S.; Grehan, A. The impact of anthropogenic activity on cold-water corals. In Marine Animal Forests; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 989–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, A.R.; Sweetman, A.K.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Jones, D.O.; Ingels, J.; Hansman, R.L. Ecosystem function and services provided by the deep sea. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 3941–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.W.; Foley, N.S.; Tinch, R.; van den Hove, S. Services from the deep: Steps towards valuation of deep-sea goods and services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Mengerink, K.; Gjerde, K.M.; Rowden, A.A.; Van Dover, C.L.; Clark, M.R.; Brider, J. Defining “serious harm” to the marine environment in the context of deep-seabed mining. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardron, J.; Arnaud-Haond, S.; Beaudoin, Y.; Bezaury, J.; Billet, D.; Boland, G.; Carr, M.; Cherkashov, G.; Cook, A.; Deleo, F.; et al. Environmental Management of Deep-Sea Chemosynthetic Ecosystems: Justification of and Considerations for a Spatially Based Approach; ISA Technical Study: No. 9; International Seabed Authority: Kingston, Jamaica, 2011; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Niner, H.J.; Ardron, J.A.; Escobar, E.G.; Gianni, M.; Jaeckel, A.; Jones, D.O.; Gjerde, K.M. Deep-sea mining with no net loss of biodiversity, An impossible aim. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.; Parker, G.; Jenner, N.; Holland, T. An Assessment of the Risks and Impacts of Seabed Mining on Marine Ecosystems; Fauna and Flora International: Cambridge, UK, 2020; 336p. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, J.J.; Gray, N.J.; Campbell, L.M.; Fairbanks, L.W.; Gruby, R.L. Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. J. Environ. Dev. 2015, 24, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbesgaard, M. Blue growth: Savior or ocean grabbing? J. Peasant. Stud. 2018, 45, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, D.; Gollner, S.; Jones, D.O.; Kaiser, S.; Arbizu, P.M.; Menzel, L.; Mestre, N.C.; Morato, T.; Pham, C.; Pradillon, F.; et al. Potential mitigation and restoration actions in ecosystems impacted by seabed mining. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Amon, D.J.; Lily, H. Challenges to the sustainability of deep-seabed mining. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalan, K.; Ratnayake, A.S.; Ratnayake, N.P.; Weththasinghe, S.M.; Dushyantha, N.; Lakmali, N.; Premasiri, R. Influence of nearshore sediment dynamics on the distribution of heavy mineral placer deposits in Sri Lanka. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, N. Sustainable exploitation of deep seabed mineral resources in the Indo-Pacific through practical cooperation under the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative. J. Indian Ocean. Reg. 2021, 17, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, L.A.; Saritas, O.; Deidun, A. Exploring future research and innovation directions for a sustainable blue economy. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105433. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayake, W. Sri Lanka’s Future: Towards a Blue Economy. Proceedings of the 78th Annual Sessions 2022—Part II, Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science. 2022. Available online: https://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/385968.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Sri Lanka; Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies. Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy: A Position Paper. UNDP Sri Lanka. 2023. Available online: https://lki.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Blue-Economy-Position-Paper_UNDP-and-LKI.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Arunashantha, H.; Lecture, A. Over Utilization of Coastal Resources and Its Impact: The Case of Sri Lanka. Soc. Investig. 2015, 1, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenkott, K.; Meyn, K.; Vink, A.; Martínez Arbizu, P. A review of megafauna diversity and abundance in an exploration area for polymetallic nodules in the eastern part of the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone (North East Pacific), and implications for potential future deep-sea mining in this area. Mar. Biodivers. 2023, 53, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, N.; Chami, R.; Sutherland, M.D.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Lebleu, L.; Benitez, M.B.; Levin, L.A. The role of blue carbon in climate change mitigation and carbon stock conservation. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 710546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.F.; Schneider, M.J.; Lozano, A.G. Toward a critical environmental justice approach to ocean equity. Environ. Justice 2025, 18, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. An Ocean of Opportunities: How the Blue Economy Can Transform Sustainable Development in Small Island Developing States; UNDP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake, E.A.; Galdolage, B.S. Opportunities, challenges, and solutions in expanding the blue economy in Sri Lanka: Special reference to the fisheries sector. Asian J. Mark. Manag. 2024, 3, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment. Biodiversity Expenditure Review; Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2017.

- Tyllianakis, E.; Ferrini, S. Personal attitudes and beliefs and willingness to pay to reduce marine plastic pollution in Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourvenec, S.; Dbouk, W.; Sturt, F.; Teagle, D.A.H. Pathways to a blue economy. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 77, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vázquez, R.M.; Milán-García, J. Challenges of the blue economy: Evidence and research trends. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Anderson, S.; Sutton, P. The future value of ecosystem services: Global scenarios and national implications. In Environmental Assessments; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B. The economics of aquatic ecosystems: An introduction to the special issue. Water Econ. Policy 2017, 3, 1702002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.C.; Croot, P.; Carlsson, J.; Colaço, A.; Grehan, A.; Hyeong, K.; Kennedy, R.; Mohn, C.; Smith, S.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. A primer for the environmental impact assessment of mining at seafloor massive sulfide deposits. Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutilla, K.; Good, D.; Toman, M.; Arin, T. Addressing fundamental uncertainty in benefit–cost analysis: The case of deep seabed mining. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 2021, 12, 122–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liu, R.; Jin, Y. Toward ecosystem-based deep-sea governance: A review of global approaches and China’s participation. Mar. Dev. 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Rovere, M. Understanding the impacts of blue economy growth on deep-sea ecosystem services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Thompson, K.F.; Johnston, P.; Santillo, D. An overview of seabed mining including the current state of development, environmental impacts, and knowledge gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 4, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedding, L.M.; Friedlander, A.M.; Kittinger, J.N.; Watling, L.; Gaines, S.D.; Bennett, M.; Smith, C.R. From principles to practice: A spatial approach to systematic conservation planning in the deep sea. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20131684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; Ardron, J.A.; Escobar, E.; Gianni, M.; Gjerde, K.M.; Jaeckel, A.; Jones, D.O.; Levin, L.A.; Niner, H.J.; Pendleton, L.; et al. Biodiversity loss from deep-sea mining. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Hynes, S.; Chen, W. Estimating the non-market benefit value of deep-sea ecosystem restoration: Evidence from a contingent valuation study of the Dohrn Canyon in the Bay of Naples. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 275, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasuriya, A. Coastal area management: Biodiversity and ecological sustainability in Sri Lankan perspective. In Biodiversity and Climate Change Adaptation in Tropical Islands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 701–724. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena, U.D. The Coastal Zone of Sri Lanka Characteristics, Problems and Prospects. In Sand Dunes of the Northern Hemisphere; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, N.; Mourato, S.; Wright, R.E. Choice modelling approaches: A superior alternative for environmental valuatioin? J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. The measurement of urban travel demand. J. Public Econ. 1974, 3, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Greene, W.H. The Mixed Logit Model: The state of practice. Transportation 2003, 30, 133–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, C.; Silver, M. Awareness of ocean literacy principles and ocean conservation engagement among American adults. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 976006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Scarpa, R. Using choice experiments to explore preferences for environmental quality under economic constraints. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde, K.M.; Weaver, P.; Billett, D.; Paterson, G.; Colaco, A.; Dale, A.; Greinert, J.; Hauton, C.; Jansen, F.; Arbizu, P.M.; et al. Report on the Implications of MIDAS Results for Policy Makers with Recommendations for Future Regulations to be Adopted by the EU and the ISA. No. December, 61. Future Regulations to be Adopted by the EU and the ISA; Seascape Consultants: Romsey, UK, 2016; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Cai, Y.; Jin, L.; Du, B. Effects on willingness to pay for marine conservation: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Yoo, S.-H. Public perspective on the environmental impacts of sea sand mining: Evidence from a choice experiment in South Korea. Resour. Policy 2020, 69, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpage, N.D.; Aanesen, M.; Armstrong, C.W. Willingness to pay for mangrove restoration to reduce the climate change impacts on ecotourism in Rekawa coastal wetland, Sri Lanka. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2022, 12, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattage, P.; Glenn, H.; Mardle, S.; Van Rensburg, T.; Grehan, A.; Foley, N. Economic Value of Conserving Deep-Sea Corals in Irish Waters: A Choice Experiment Study on Marine Protected Areas. Fish. Res. 2011, 107, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subroy, V.; Rogers, A.A.; Kragt, M.E. To bait or not to bait: A discrete choice experiment on public preferences for native wildlife and conservation management in Western Australia. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.W.; Atkinson, G.; Mourato, S. Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Recent Developments; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, N.C.; Mills, M.; Tam, J. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: Embedding social considerations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Description | Levels |

|---|---|---|

Extraction of minerals  | The percentage of minerals and resources extracted from mining | 10% 30% 0% |

Deterioration of sea water quality  | The percentage deterioration in the sea water quality due to the emission of nutrients, heavy metals, and organic matter concentrated in the sediments due to mining | 15% 30% 0% |

Destruction of biodiversity and habitats  | The percentage destruction of bio diversity and habitat due to mining | 10% 25% 0% |

Monitoring and regulation  | Level of governance and enforcement | Current state of governance More stringent regulation Improved community participation |

Price  | Amount willing to pay for conservation per month | LKR 100 LKR 250 LKR 500 |

| Variable | Category | Percentage of Respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 61.8 |

| Male | 38.2 | |

| Age (Years) | Less than 18 | 1.6 |

| 20 to 30 | 55.4 | |

| 31 to 45 | 30.6 | |

| 46 to 60 | 12.4 | |

| Above 60 | 0 | |

| Employment | Fisheries/Environment related | 7.3 |

| Government sector job | 11.4 | |

| NGO | 3.3 | |

| Private sector job | 11.4 | |

| Self-employed | 4.1 | |

| Student | 8.1 | |

| Retired | 0 | |

| Unemployed | 52.8 | |

| Other | 1.6 | |

| Education Level | Primary Education | 0 |

| Secondary Education | 9.8 | |

| Diploma | 24.9 | |

| First Degree | 54.0 | |

| Master’s Degree | 8.1 | |

| Doctorate | 0.8 | |

| Professional Qualification | 2.4 | |

| Monthly Income (Sri Lankan Rupees [LKR]) | Less than 50,000 | 9.8 |

| 50,001 to 100,000 | 63.70 | |

| 100,001 to 200,000 | 22.44 | |

| 200,001 to 500,000 | 3.25 | |

| Over 500,000 | 0.81 |

| Statement | Percentage of Respondents (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I have heard of deep seabed mining activities in the country | 31 | 46 | 14 | 10 | 0 |

| I want to learn more about deep seabed mining | 10 | 8 | 8 | 45 | 29 |

| Marine environment is very important to me | 13 | 4 | 11 | 22 | 50 |

| I believe seabed mining is harmful to coral reefs and other sensitive ecosystems | 13 | 7 | 4 | 24 | 52 |

| There is no significant impact on my beach activities due to seabed mining | 28 | 25 | 24 | 14 | 9 |

| We need more stringent policies to control seabed mining | 16 | 15 | 35 | 28 | 6 |

| Media has not done enough to mobilize the public on this issue | 15 | 5 | 11 | 36 | 33 |

| Government authorities have not done enough for seabed conservation | 14 | 7 | 14 | 39 | 26 |

| Public awareness is essential for seabed protection | 13 | 8 | 19 | 41 | 20 |

| I’m willing to engage in seabed conservation activities | 15 | 28 | 14 | 33 | 10 |

| Seabed Mining and Other Operations | Provisioning Services | Regulating Services (Maintaining Environmental Balance) | Supporting Services (Essential for Ecosystem Functioning) | Cultural and Recreational Services (Human Connection to the Ocean) | ||||||||||||

| Food supply | Raw materials | Pharmaceutical compounds | Energy resources | Carbon sequestration | Nutrient cycling | Water purification | Coastal protection | Habitat provision | Biodiversity maintenance | Primary production | Tourism and recreation | Spiritual and cultural significance | Scientific and educational value | |||

| Seabed | Deep-sea mining—Extraction of valuable minerals | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | |

| Oil and gas drilling | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | ||

| Sand and gravel extraction | − | + | − | - | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Dredging—Removal of sediments for navigation, construction, or resource extraction | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Infrastructure Development | Energy project installation, i.e., wind farms and tidal energy | ± | ± | ± | + | + | ± | ± | + | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | + | |

| Artificial reefs and marine structures | + | − | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Seabed Conservation and Management | Marine protected areas (MPAs) | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Seabed habitat restoration | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Sustainable fisheries management ng | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Scientific Research and Exploration | Deep-sea exploration | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | + | |

| Climate change research | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | + | ||

| Archaeological investigations | − | − | ± | − | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | + | + | + | ||

| Attribute Variables | CL | RPL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | MWTP | Coeff. | SE | MWTP | |

| ASC | 1.1625 | 0.710 | 0.433 | 1.830 | ||

| Extraction of minerals (30%) (EXM1) | −0.182 | 0.256 | 78.48 | 0.048 | 0.328 | 1605.96 |

| Extraction of minerals (10%) (EXM2) | 0.347 * | 0.140 | 1314 | 0.894 * | 0.491 | 1618.02 |

| Deterioration of the sea water quality (15%) (SWQ1) | −0.068 | 0.126 | 1661.52 | 0.0684 | 0.287 | 774 |

| Deterioration of the sea water quality (30%) (SWQ2) | −0.227 | 0.224 | 1047.24 | 0.174 | 0.115 | 775.98 |

| Destruction of biodiversity and habitats (10% reduction) (BDH1) | 0.006 * | 0.011 | 112.86 | 0.010 * | 0.002 | 1191.96 |

| Destruction of biodiversity and habitats (25% reduction) (BDH2) | 0.445 * | 0.144 | 178.38 | 1.476 * | 0.546 | 1380.06 |

| Monitoring and regulation 1 (stringent) (MRG1) | 0.123 | 0.144 | 0.09 | 0.564 * | 0.669 | 774 |

| Monitoring and regulation 2 (community) (MRG1) | 0.191 | 0.129 | 0.61 | 0.672 | 0.332 | 775.98 |

| Price | 0.015 * | 0.036 | 0.069 * | 0.048 | ||

| Age | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.064 | 0.023 | ||

| Income | 0.217 * | 0.246 | 0.975 * | 0.274 | ||

| Gender | 0.832 * | 0.127 | 0.922 | |||

| Log-likelihood | 1017.36 | 1065.21 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ganepola, N.; Udugama, M.; Udayanga, L.; De Silva, S. Deep-Sea Dilemmas: Evaluation of Public Perceptions of Deep-Sea Mineral Mining and Future of Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy. Sustainability 2026, 18, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010440

Ganepola N, Udugama M, Udayanga L, De Silva S. Deep-Sea Dilemmas: Evaluation of Public Perceptions of Deep-Sea Mineral Mining and Future of Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010440

Chicago/Turabian StyleGanepola, Nethini, Menuka Udugama, Lahiru Udayanga, and Sudarsha De Silva. 2026. "Deep-Sea Dilemmas: Evaluation of Public Perceptions of Deep-Sea Mineral Mining and Future of Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010440

APA StyleGanepola, N., Udugama, M., Udayanga, L., & De Silva, S. (2026). Deep-Sea Dilemmas: Evaluation of Public Perceptions of Deep-Sea Mineral Mining and Future of Sri Lanka’s Blue Economy. Sustainability, 18(1), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010440