Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean

Abstract

1. Introduction

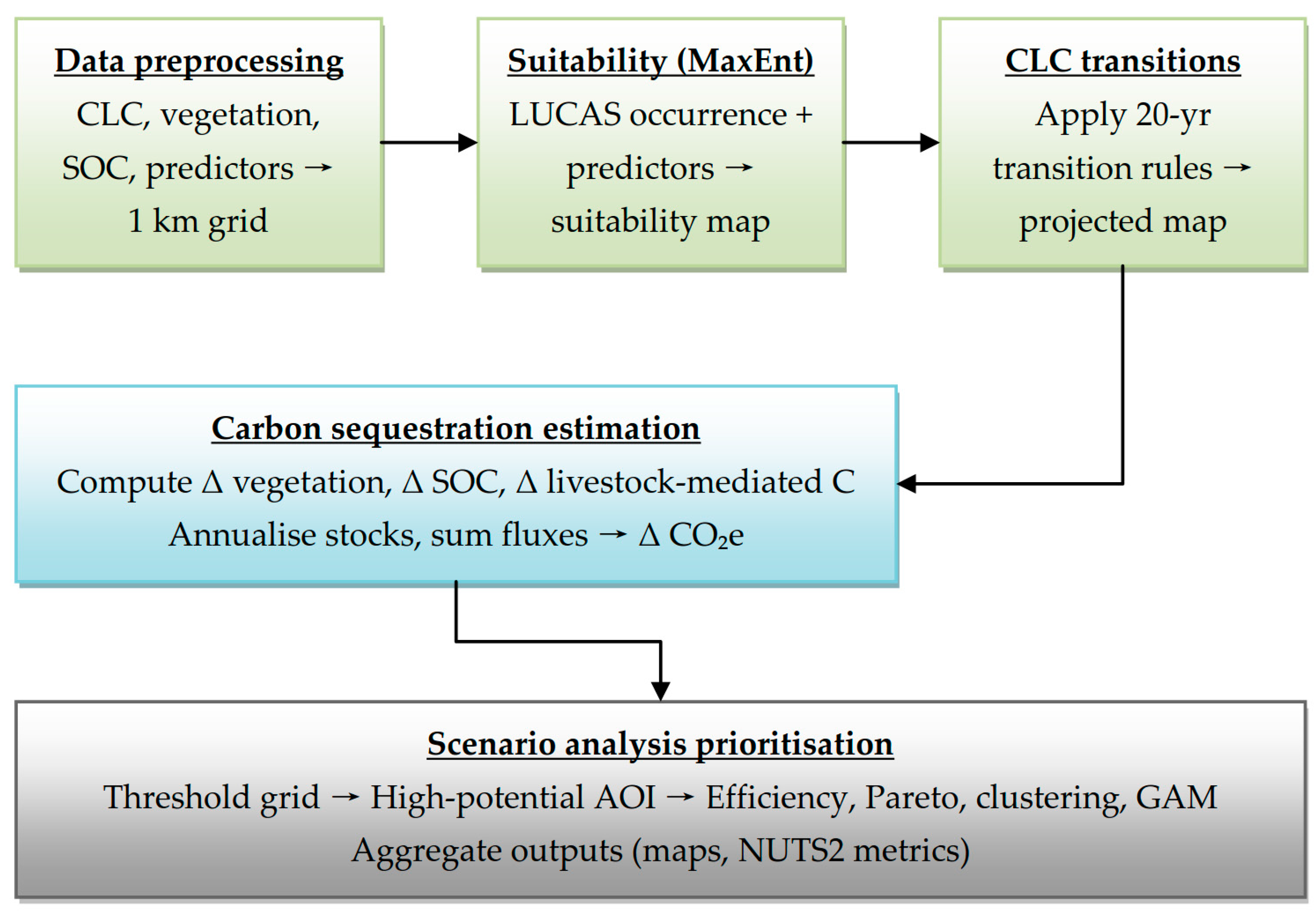

2. Materials and Methods

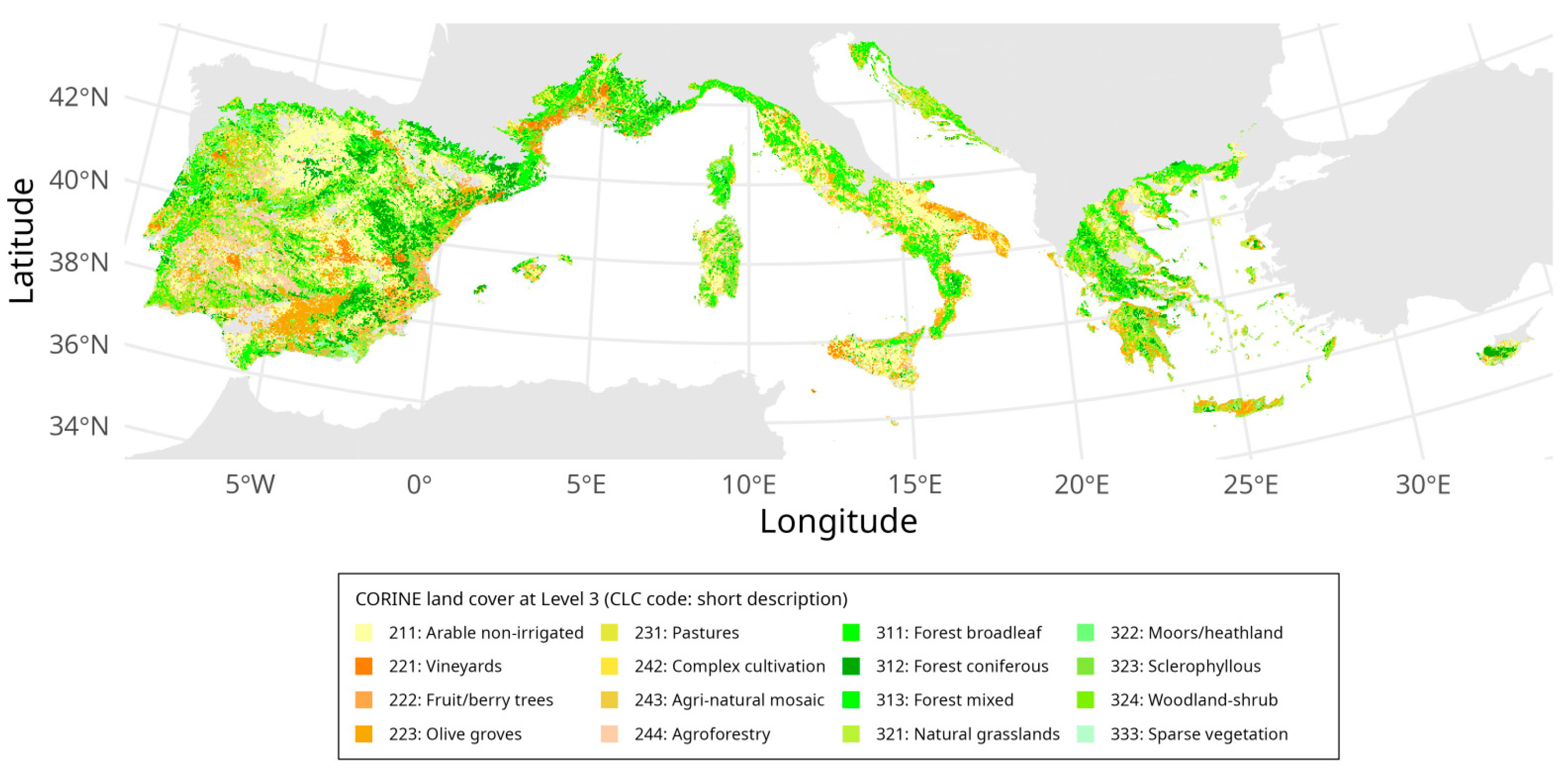

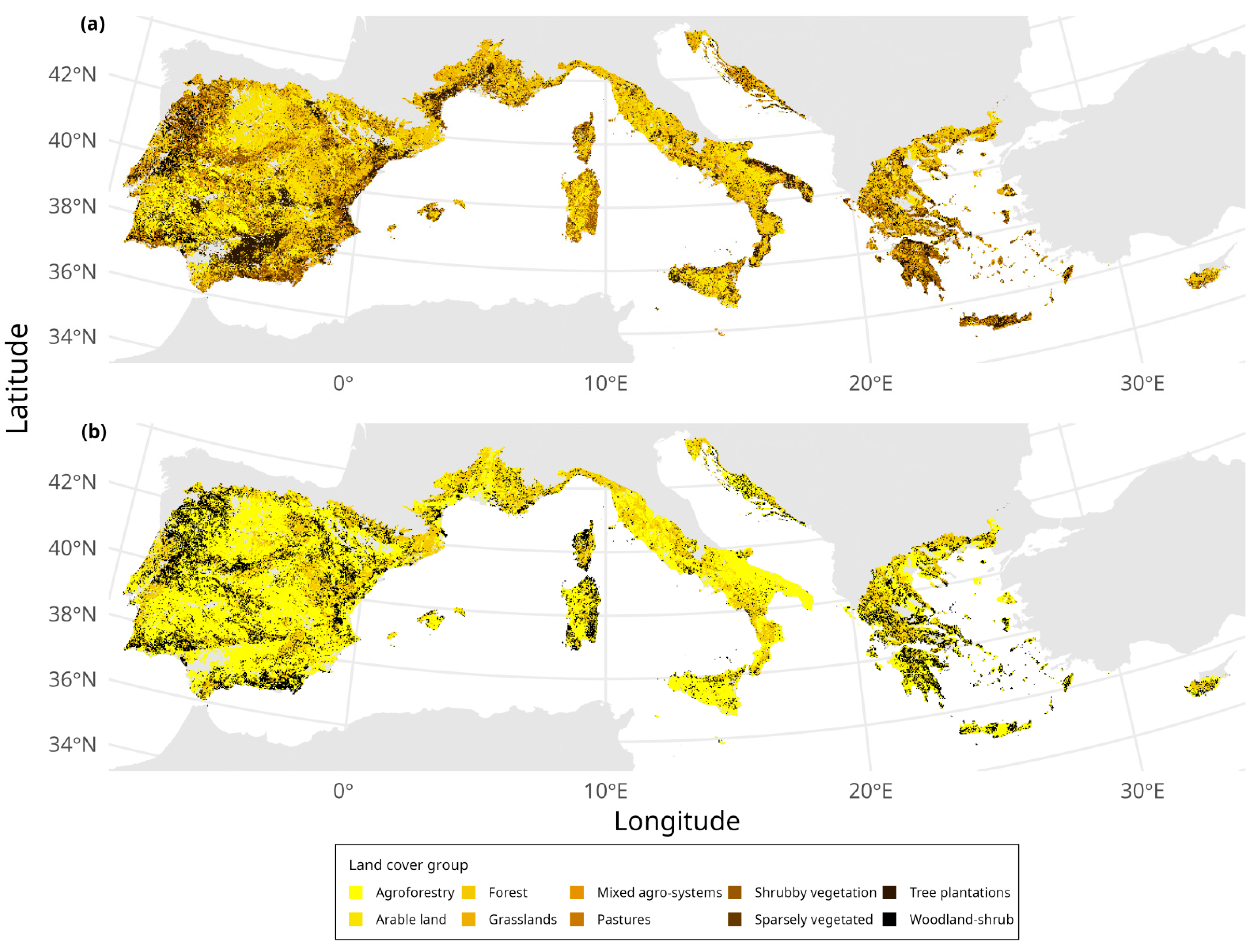

2.1. Study Region and Baseline Land Cover

2.2. Silvopastoralism Suitability Modelling

2.2.1. Silvopastoralism Occurrence Data

2.2.2. Ecological and Socioeconomic Predictors

- Bioclimatic variables: Four variables were sourced from the WorldClim 2.1 dataset [56]: annual mean temperature (BIO1), temperature seasonality (standard deviation × 100, BIO4), annual precipitation (BIO12), and precipitation seasonality (coefficient of variation in percentage, BIO15). These were processed from their native 30 s resolution, reprojected, resampled to the 1 km grid, and finally classified to ordinal levels (Figure S3).

- Soil properties: Three topsoil (0–30 cm) variables were obtained from the European Soil Database (ESDB) of the JRC [58]: total organic carbon content (TOC), total available water content (TAWC), and soil texture class (TTEXT). These were reclassified into ordinal levels, or categories based on their original documentation, and resampled to the 1 km grid (Figure S5).

- Socioeconomic variables: Three NUTS3-level indicators for the year 2022 were sourced from Eurostat: median population age [59], population density [60], and employment rate for ages 15–64, i.e., percentage of the population in the 15–64 year range [61] that is employed [62]. These vector-based data were rasterized to the 1 km grid. Missing values were imputed using the mean of neighbouring NUTS3 regions, with a country-level median as a fallback (Figure S6).

2.2.3. MaxEnt Model Implementation and Selection

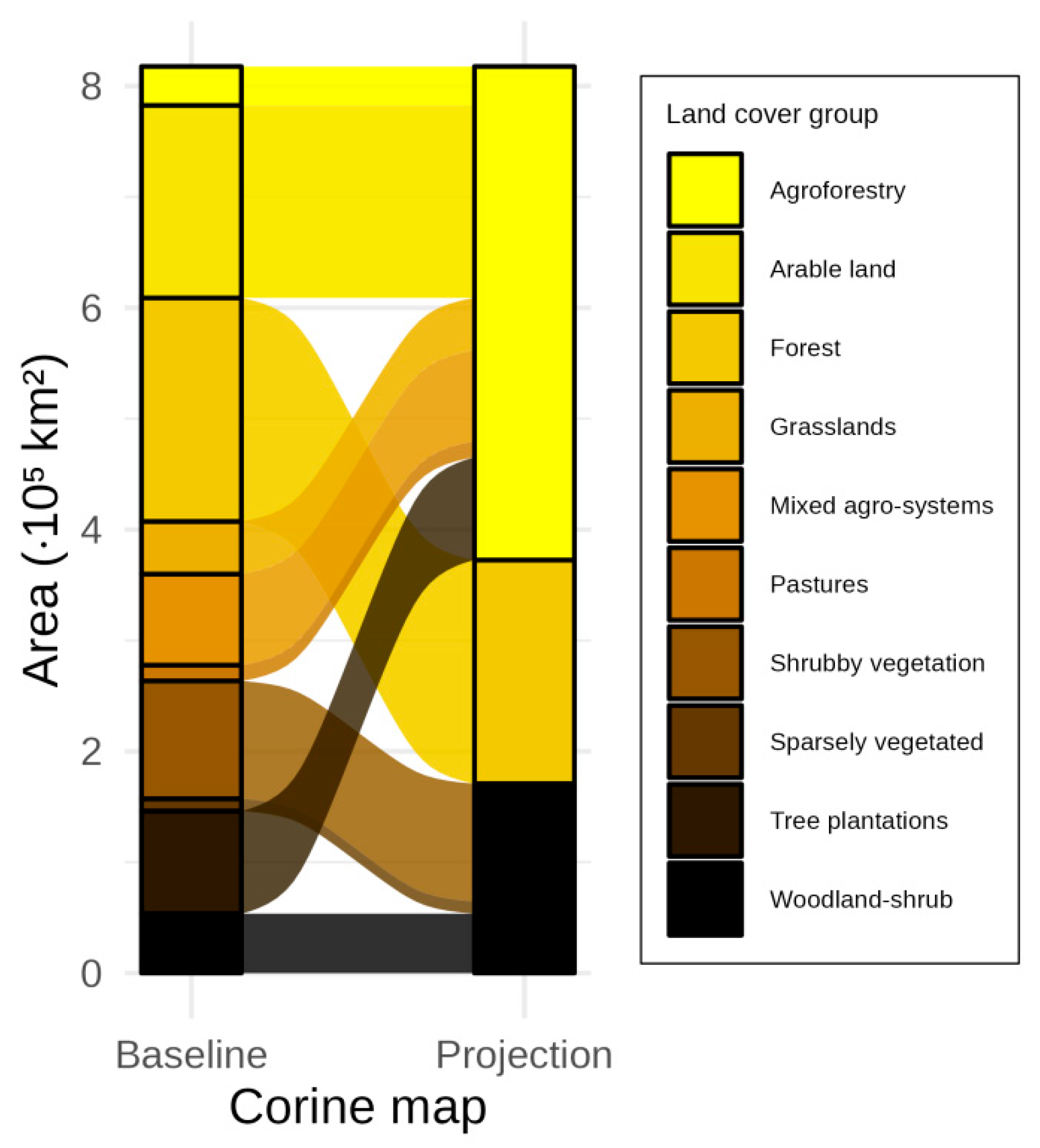

2.3. Projection of Land Cover to Silvopastoralism Transition

- Non-irrigated arable land (211), Vineyards (221), Fruit trees (222), Olive groves (223), Pastures (231), Complex cultivation (242), Agri-natural mosaic (243), and Natural grasslands (321) were transitioned to Agroforestry (244).

- Sclerophyllous vegetation (323), Moors and heathland (322), and Sparsely vegetated areas (333) were transitioned to Transitional woodland-shrub (324).

2.4. Carbon Sequestration Modelling

- Above- and below-ground vegetation carbon stock.

- Soil organic carbon (SOC) stock.

- Livestock-mediated carbon sequestration from manure deposition.

2.4.1. Vegetation Carbon Stock

- Primary: Mean of 10 nearest neighbours with the same target land cover and environmental group.

- Fallback 1: Mean of fewer than 10 nearest neighbours with the same target land cover and environmental group (at least one neighbour required).

- Fallback 2: Mean of 10 nearest neighbours with only the same target land cover.

- Fallback 3: Mean of 10 nearest neighbours with only the same levels of environmental conditions.

- Fallback 4: If no analogues are found, the pixel retains its baseline carbon value.

2.4.2. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Stock

2.4.3. Livestock-Mediated Carbon Sequestration

- Carbon Intake (): Annual carbon intake was calculated as the product of annual dry matter intake and the carbon content of forage dry matter which was assumed to be 45% [70]:was estimated as the percentage of animal body weight , using values of 2.5% for cattle [71] and 4.0% for sheep/goats [72]:was assumed to be 365 kg and 45 kg for cattle and sheep/goats, respectively [71,72].

- Carbon Outflows (): Carbon outflows were partitioned into the following pathways:

- ○

- Animal Products (from milk and growth): Carbon exported in milk and new body tissue was subtracted. This was calculated using literature-derived values for annual milk yield assumed to be 3500 kg and 400 kg for, respectively, the cattle and sheep/goats [73,74], the carbon content of milk assumed to be 11% of its weight [75], annual body growth assumed to be approximately 65 kg and 123 kg for, respectively, and cattle and sheep/goats [76], and carbon content of body tissue assumed to be approximately 19% and 15% for respectively the cattle and sheep/goats [77].

- ○

- Respiration (): Carbon lost as CO2 through maintenance respiration was estimated. We first calculated the maintenance energy requirement scaled by metabolic body weight (), relative to a reference weight for expressing results per LSU (650 kg) [78]. This maintenance energy (MJ day−1) was converted to CO2 production using a fixed energy-to-CO2 factor (0.07 kg CO2 MJ−1) [79]. The carbon percent of DMI (45%) provided the ingested carbon, while 27.3% of CO2 mass corresponds to carbon [80]. The resulting carbon respired, and percentage of ingested carbon lost as CO2, quantify respiration-related carbon turnover per animal.

- ○

- Methane Emissions (): Carbon lost as methane (CH4) from enteric fermentation and manure management was assumed to be 87 kg CH4 LSU−1 year−1 and 8 kg CH4 LSU−1 year−1 for cattle and sheep/goats, respectively [64]. The mass of methane was converted to the mass of carbon using the molar mass ratio of carbon to methane (12/16).

- Net Manure Carbon Input (): The carbon remaining for deposition as manure was calculated as the residual of intake minus all outflows:

- Final Sequestered Carbon (): The amount of manure carbon that becomes stabilised in the soil was estimated by applying a sequestration efficiency coefficient () to the net manure C input. This coefficient represents the fraction of deposited carbon that is incorporated into long-term SOC pools. Based on meta-analyses of manure application studies, we used efficiency values of 15% for cattle [81], and 30% for sheep/goats [82]. The model assumes uniform manure deposition and does not account for non-linear density effects such as soil compaction:

2.5. Scenario Analysis Framework for Identifying High-Potential Areas

- Minimum slope: We tested thresholds of 1°, 3°, 5°, 7°, 10°, 15°, and 20°. Pixel slope was given from the continuous version of the slope raster (Figure S4c).

- Minimum silvopastoralism suitability: We tested thresholds from 0.3 to 0.9 with a 0.1 increment. This threshold was based on the map of predicted suitability from the previously developed MaxEnt SDM (Figure S7).

- Maximum tree cover density: Thresholds ranged from 10% to 60% with a 10% increment. Tree cover density for the study area was derived from 2021 GLOBMAP Fractional Tree Cover tiles [84]. We applied a mosaicking of all MODIS sinusoidal tiles intersecting the area of interest, reprojecting the mosaic to the EPSG:3035 grid, and resampling it to 1 km resolution. Remaining data gaps were filled using an 11 × 11 median focal filter and global mean fallback (Figure S16).

- Maximum livestock density: We tested thresholds 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 1.0 LSU ha−1 from the baseline map of LSU density (summing the LSU densities from cattle and sheep/goats in Figure S12a,b, respectively).

- Land protection status (strict versus relaxed): We hypothesised two protection regimes: strict versus relaxed. Initially, a protected areas map was created by merging the Natura 2000 sites (Birds and Habitats Directives; types B and C) [85], and the CDDA national designations (IUCN Ia–III and equivalent strict conservation categories) [86]. Both datasets were reprojected to the EPSG:3035 grid, clipped to the study extent, simplified, and dissolved into a single exclusion mask that identifies zones that could be restricted from agroforestry or land-use modification (Figure S17). We defined two policy regimes regarding the protected areas:

- Strict regime: All protected areas were excluded from consideration.

- Relaxed regime: Protected areas were excluded unless they already supported grazing (LSU density greater than 0 LSU ha−1), acknowledging that some forms of agriculture are permissible in certain designated areas.

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Scenario Prioritisation

3. Results

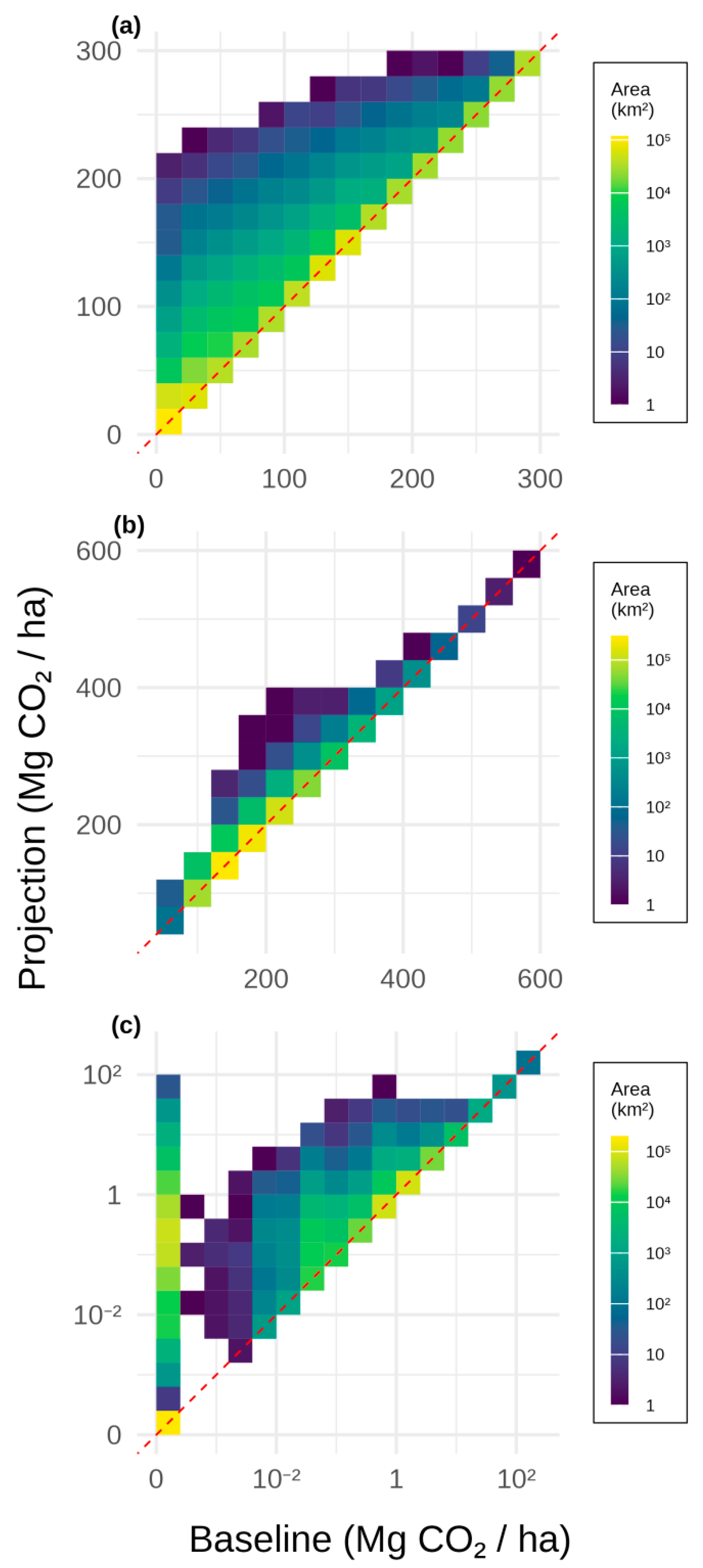

3.1. Carbon Stock Changes from Baseline to Projection

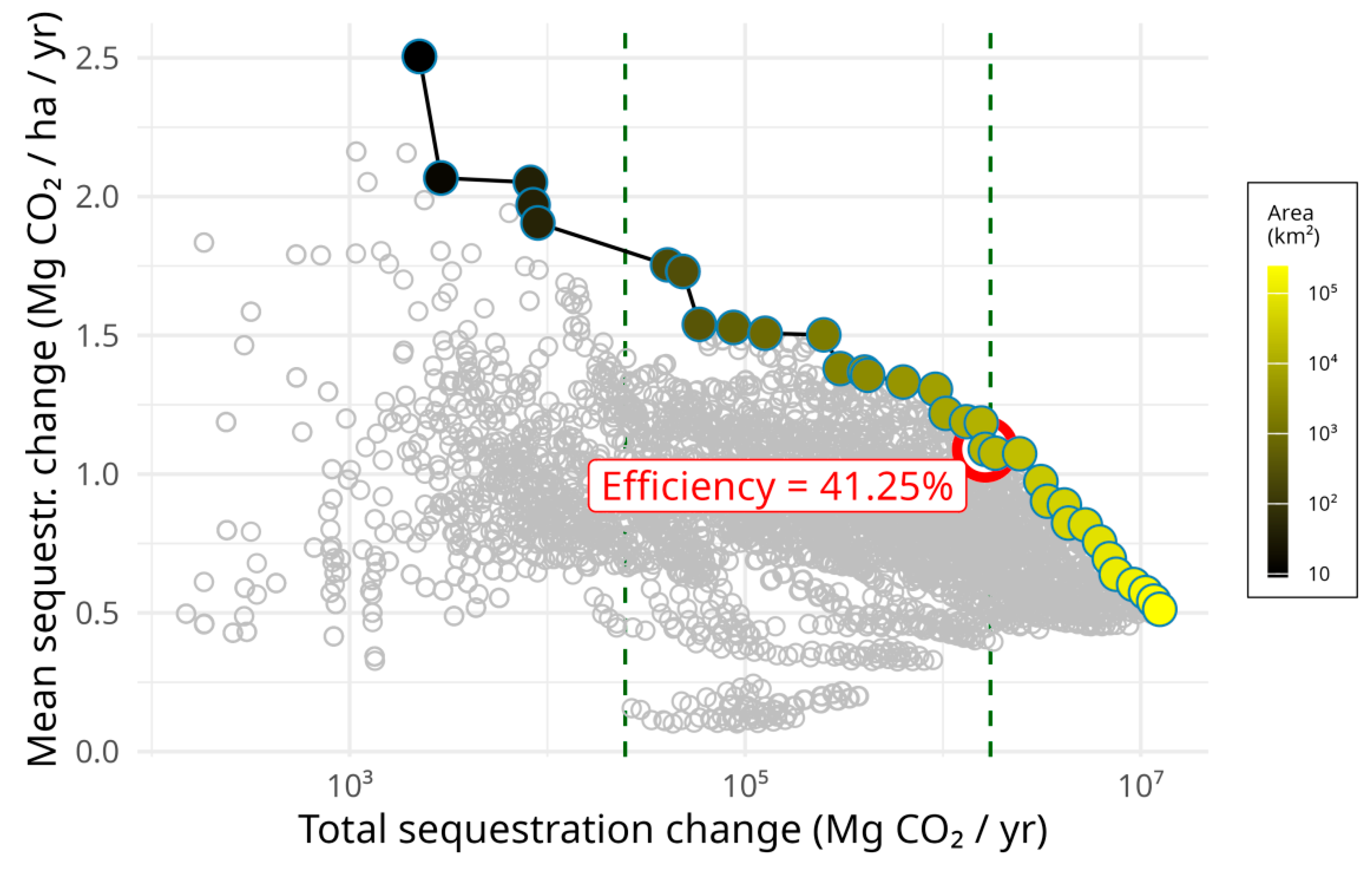

3.2. Scenario Analysis and Identification of Optimal Strategies

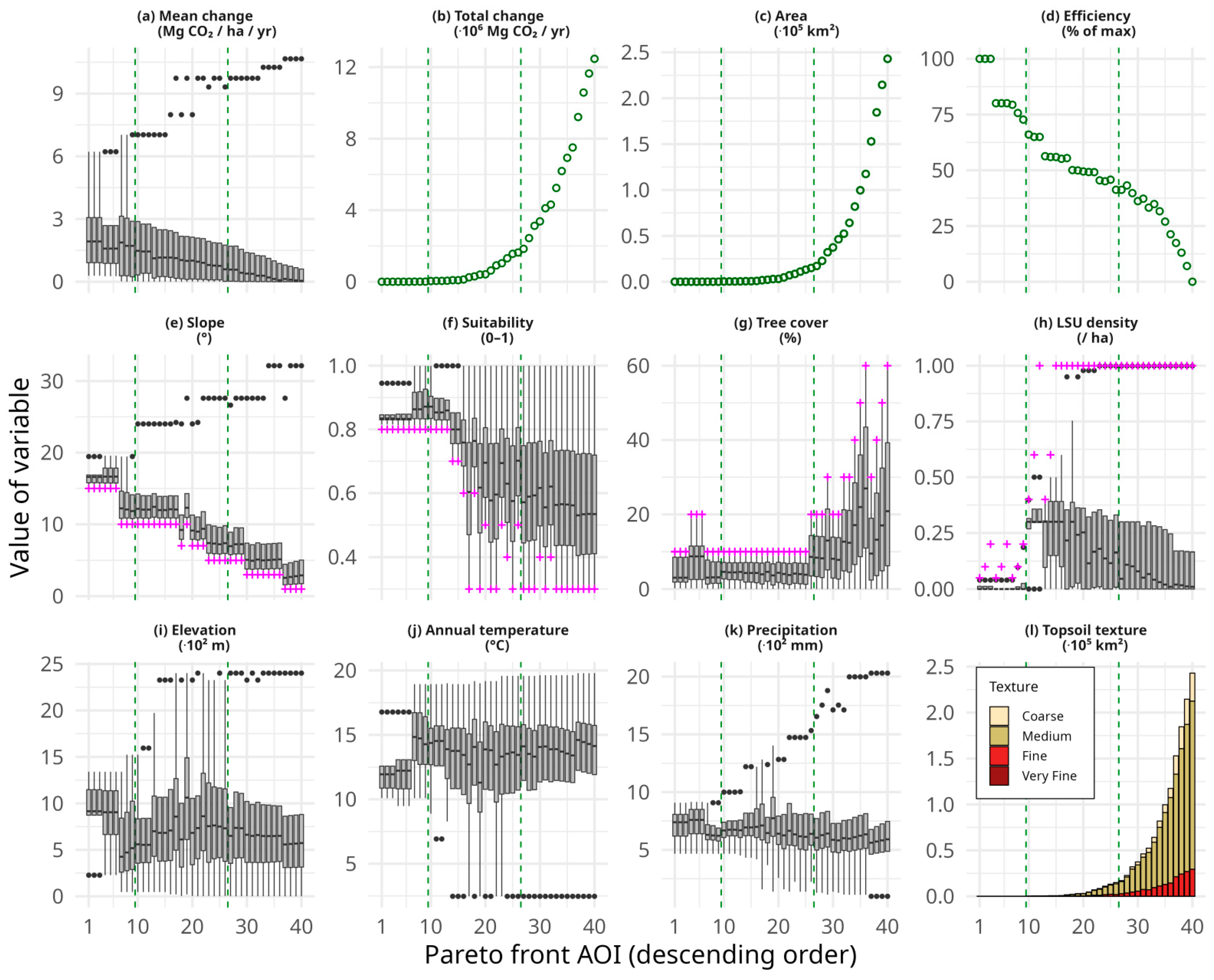

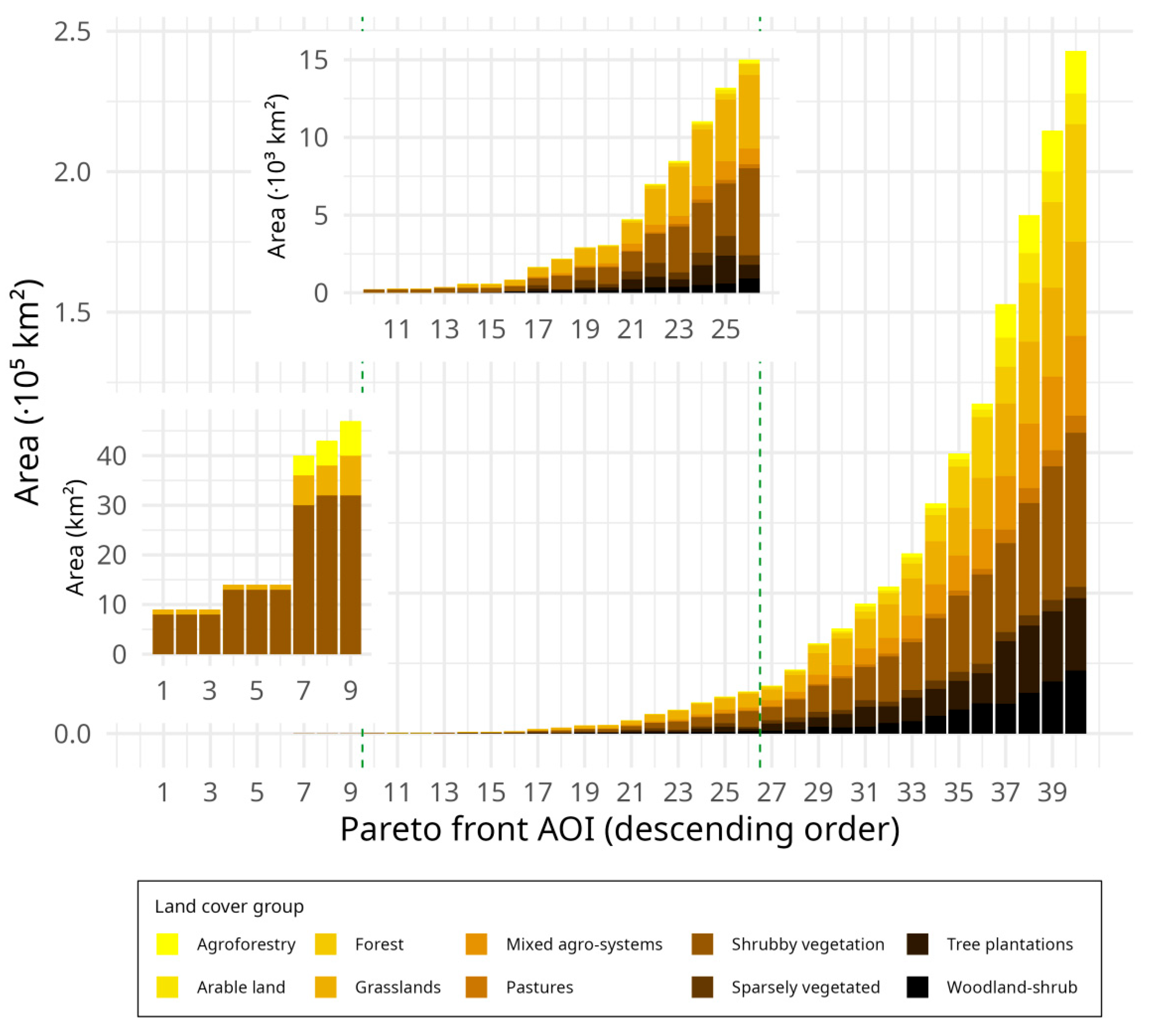

3.3. Drivers of Sequestration Potential Along the Pareto Front

3.4. High Potential for Sequestration Change at the Administrative Level

3.5. Key Drivers of Carbon Sequestration Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Total and Mean Carbon Sequestration Rates

4.2. Policy Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030—Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Official Journal of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2018/841 on the Inclusion of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework, and Amending Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 and Decision No 529/2013/EU; L 156, 19.6.2018; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Enhancing Europe’s Land Carbon Sink: Status and Prospects. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/2836317 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Dong, H.; Elsiddig, E.A.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 811–922. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Calvin, K.; Nkem, J.; Campbell, D.; Cherubini, F.; Grassi, G.; Korotkov, V.; Le Hoang, A.; Lwasa, S.; McElwee, P.; et al. Which Practices Co-deliver Food Security, Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation, and Combat Land Degradation and Desertification? Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1532–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for Ecosystem Services and Environmental Benefits: An Overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K.R. Agroforestry Systems and Environmental Quality: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnini, F.; Nair, P.K.R. Carbon Sequestration: An Underexploited Environmental Benefit of Agroforestry Systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 61–62, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.M.; Nair, P.K.R. The Enigma of Tropical Homegardens. In New Vistas in Agroforestry; Nair, P.K.R., Rao, M.R., Buck, L.E., Eds.; Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 135–152. ISBN 978-90-481-6673-2. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, A.; Jacobson, M.G. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Agroforestry Systems: A Meta-Analysis. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinael, R.; Guenet, B.; Chevallier, T.; Dupraz, C.; Cozzi, T.; Chenu, C. High Organic Inputs Explain Shallow and Deep SOC Storage in a Long-Term Agroforestry System—Combining Experimental and Modeling Approaches. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Höchtl, F.; Spek, T. Traditional Land-Use and Nature Conservation in European Rural Landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Santos, M.G.S.; Gonçalves, B.; Ferreiro-Domínguez, N.; Castro, M.; Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A.; González-Hernández, M.P.; Fernández-Lorenzo, J.L.; Romero-Franco, R.; Aldrey-Vázquez, J.A.; et al. Policy Challenges for Agroforestry Implementation in Europe. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1127601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranchina, M.; Reubens, B.; Frey, M.; Mele, M.; Mantino, A. What Challenges Impede the Adoption of Agroforestry Practices? A Global Perspective through a Systematic Literature Review. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 1817–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Eco-Schemes. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/income-support/eco-schemes_en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Schwartz, M.W.; Cook, C.N.; Pressey, R.L.; Pullin, A.S.; Runge, M.C.; Salafsky, N.; Sutherland, W.J.; Williamson, M.A. Decision Support Frameworks and Tools for Conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, S.E.; Miller, D.C.; Merten, N.; Ordonez, P.J.; Baylis, K. Evidence for the Impacts of Agroforestry on Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Map. Environ. Evid. 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughran, T.F.; Ziehn, T.; Law, R.; Canadell, J.G.; Pongratz, J.; Liddicoat, S.; Hajima, T.; Ito, A.; Lawrence, D.M.; Arora, V.K. Limited Mitigation Potential of Forestation Under a High Emissions Scenario: Results from Multi-Model and Single Model Ensembles. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2023, 128, e2023JG007605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Lawrence, D.M.; Pan, M.; Zhang, B.; Graham, N.T.; Lawrence, P.J.; Liu, Z.; He, X. A Bioenergy-Focused versus a Reforestation-Focused Mitigation Pathway Yields Disparate Carbon Storage and Climate Responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2306775121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonça, G.C.; Da Costa, L.M.; Abdo, M.T.V.N.; Costa, R.C.A.; Parras, R.; De Oliveira, L.C.M.; Pissarra, T.C.T.; Pacheco, F.A.L. Multicriteria Spatial Model to Prioritize Degraded Areas for Landscape Restoration through Agroforestry. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; O’Grady, A.; Mendham, D.; Smith, G.; Smethurst, P. Digital Tools for Quantifying the Natural Capital Benefits of Agroforestry: A Review. Land 2022, 11, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Integrating Forest Restoration into Land-Use Planning at Large Spatial Scales. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R452–R472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, I.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Watts, M.E. Marxan and Relatives: Software for Spatial Conservation Prioritization. In Spatial Conservation Prioritization; Moilanen, A., Wilson, K.A., Possingham, H.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 185–195. ISBN 978-0-19-954776-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtomäki, J.; Moilanen, A. Methods and Workflow for Spatial Conservation Prioritization Using Zonation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 47, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicuaio, T.; Zhao, P.; Pilesjo, P.; Shindyapin, A.; Mansourian, A. Sustainable and Resilient Land Use Planning: A Multi-Objective Optimization Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren Raffa, D.; Räsänen, T.A.; Trinchera, A.; Jouini, M.; Delin, S.; Kasparinskis, R.; Dirnēna, B.; Demir, Z.; Erdal, Ü.; Hanegraaf, M. Agricultural Decision Support Tools in Europe: What Kind of Tools Are Needed to Foster Soil Health? Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 76, e70097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, D.; Karmiris, I.; Kiziridis, D.A.; Astaras, C.; Papachristou, T.G. Social-Ecological Spatial Analysis of Agroforestry in the European Union with a Focus on Mediterranean Countries. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, M.; Olazabal, M.; Fokaides, P.A.; Tardieu, L.; Simoes, S.G.; Geneletti, D.; De Gregorio Hurtado, S.; Viguié, V.; Spyridaki, N.-A.; Pietrapertosa, F.; et al. Climate Mitigation in the Mediterranean Europe: An Assessment of Regional and City-Level Plans. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, J.; Aronson, J. Biology and Wildlife of the Mediterranean Region; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-850036-0. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D. Plant Evolution in the Mediterranean; Oxford Biology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-851534-0. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural Abandonment in Mountain Areas of Europe: Environmental Consequences and Policy Response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziridis, D.A.; Mastrogianni, A.; Pleniou, M.; Karadimou, E.; Tsiftsis, S.; Xystrakis, F.; Tsiripidis, I. Acceleration and Relocation of Abandonment in a Mediterranean Mountainous Landscape: Drivers, Consequences, and Management Implications. Land 2022, 11, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiris, I.; Papachristou, T.G.; Fotakis, D. Abandonment of Silvopastoral Practices Affects the Use of Habitats by the European Hare (Lepus europaeus). Agriculture 2022, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, E.; Serrano, J.; Lopes De Castro, J.; Shahidian, S.; Pereira, A.F. Montado Mediterranean Ecosystem (Soil–Pasture–Tree and Animals): A Review of Monitoring Technologies and Grazing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-López, C.; Sayadi, S.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Ben Abdallah, S.; Carmona-Torres, C. Prioritising Conservation Actions towards the Sustainability of the Dehesa by Integrating the Demands of Society. Agric. Syst. 2023, 206, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edris, S.; Gabourel-Landaverde, V.A.; Schnabel, S.; Rubio-Delgado, J.; Olave, R. Contribution of European Agroforestry Systems to Climate Change Mitigation: Current and Future Land Use Scenarios. Land 2025, 14, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecegui, A.; Olaizola, A.; Kok, K.; Varela, E. What Shapes Silvopastoralism in Mediterranean Mid-Mountain Areas? Understanding Factors, Drivers, and Dynamics Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, art27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, E.; Olaizola, A.M.; Blasco, I.; Capdevila, C.; Lecegui, A.; Casasús, I.; Bernués, A.; Martín-Collado, D. Unravelling Opportunities, Synergies, and Barriers for Enhancing Silvopastoralism in the Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2022, 118, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A.; McAdam, J.H.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R. Agroforestry in Europe: Current Status and Future Prospects; Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4020-8271-9. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, S.; Streck, C.; Beach, R.; Busch, J.; Chapman, M.; Daioglou, V.; Deppermann, A.; Doelman, J.; Emmet-Booth, J.; Engelmann, J.; et al. Land-based Measures to Mitigate Climate Change: Potential and Feasibility by Country. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 6025–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Smiraglia, D.; Quaranta, G.; Salvia, R.; Salvati, L.; Giménez-Morera, A. Land Degradation and Mitigation Policies in the Mediterranean Region: A Brief Commentary. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriacò, M.V.; Dămătîrcă, C.; Abd Alla, S.; Barilari, S.; Biancardi Aleu, R.; Brazzini, T.; Capela Lourenço, T.; De Carolis Villars, C.A.; Durand, S.; Di Lallo, G.; et al. A Catalogue of Land-Based Adaptation and Mitigation Solutions to Tackle Climate Change. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Hijmans, R.J. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Hernangómez, D. Using the Tidyverse with Terra Objects: The Tidyterra Package. J. Open Source Softw. 2023, 8, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Corine Land Cover Classes. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/content/corine-land-cover-nomenclature-guidelines/html/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Biogeographical Regions. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/11db8d14-f167-4cd5-9205-95638dfd9618 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- CORINE Land Cover 2018 (Vector/Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover/clc2018 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Merow, C.; Smith, M.J.; Silander, J.A. A Practical Guide to MaxEnt for Modeling Species’ Distributions: What It Does, and Why Inputs and Settings Matter. Ecography 2013, 36, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Statistical Office of the European Union; Publications Office. New LUCAS 2022 Sample and Subsamples Design: Criticalities and Solutions, 2022nd ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. LUCAS 2022: Data for All Countries. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lucas/database/2022 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Elith, J.; Phillips, S.J.; Hastie, T.; Dudík, M.; Chee, Y.E.; Yates, C.J. A Statistical Explanation of MaxEnt for Ecologists: Statistical Explanation of MaxEnt. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Herder, M.; Moreno, G.; Mosquera-Losada, R.M.; Palma, J.H.N.; Sidiropoulou, A.; Santiago Freijanes, J.J.; Crous-Duran, J.; Paulo, J.A.; Tomé, M.; Pantera, A.; et al. Current Extent and Stratification of Agroforestry in the European Union. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neteler, M.; Haas, J.; Metz, M. Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (DEM) for Europe at 100 Meter Resolution (EU-LAEA) Derived from Copernicus Global 30 Meter DEM Dataset. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/74d0e58f-9f51-444e-a5a7-eff4c20f05b1~~1?locale=en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Jones, A.; Montanarella, L. European Soil Data Centre: Response to European Policy Support and Public Data Requirements. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Population Structure Indicators by NUTS 3 Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/DEMO_R_PJANIND3 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Population Density by NUTS 3 Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/DEMO_R_D3DENS (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by Age Group, Sex and NUTS 3 Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/DEMO_R_PJANGRP3 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Emploi (Milliers de Personnes) Par Région NUTS 3. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/NAMA_10R_3EMPERS (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Boria, R.A.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; Anderson, R.P. ENMeval: An R Package for Conducting Spatially Independent Evaluations and Estimating Optimal Model Complexity for MaxEnt Ecological Niche Models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Mangino, J.; McAllister, T.A.; Hatfield, J.L.; Johnson, D.E.; Lassey, K.R.; Aparecida de Lima, M.; Romanovskaya, A. Emissions from Livestock and Manure Management. In 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Volume 4: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2006; pp. 10.1–10.87. [Google Scholar]

- Tadese, S.; Soromessa, T.; Aneseye, A.B.; Gebeyehu, G.; Noszczyk, T.; Kindu, M. The Impact of Land Cover Change on the Carbon Stock of Moist Afromontane Forests in the Majang Forest Biosphere Reserve. Carbon Balance Manag. 2023, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulckaen, A.; Crespo, R. Vegetation Carbon Stock 2001–2020. Available online: https://data.integratedmodelling.org/dataset/global-vegetation-carbon-stock-2001-2020 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Poggio, L.; de Sousa, L.M.; Batjes, N.H.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing Soil Information for the Globe with Quantified Spatial Uncertainty. Soil 2021, 7, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Ž.; Romanchuk, Z.; Yashschun, O.; See, L. Spatial Distribution of Cattle, Sheep and Goat Density, and Grazed Areas for the European Union and the United Kingdom [Zenodo Data Set]. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/13734518 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Malek, Ž.; Romanchuk, Z.; Yaschun, O.; Jones, G.; Petersen, J.-E.; Fritz, S.; See, L. Improving the Representation of Cattle Grazing Patterns in the European Union. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; He, F.; Tian, D.; Zou, D.; Yan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Huang, K.; Shen, H.; Fang, J. Variations and Determinants of Carbon Content in Plants: A Global Synthesis. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, H.M.; Brennan, J.R.; Ehlert, K.A.; Parsons, I.L. Improving Dry Matter Intake Estimates Using Precision Body Weight on Cattle Grazed on Extensive Rangelands. Animals 2023, 13, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primary Industries Standing Committee. Nutrient Requirements of Domesticated Ruminants; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2007; ISBN 978-0-643-09510-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.; Aboshady, H.M.; Agamy, R.; Archimede, H. Milk Production and Composition in Warm-Climate Regions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.M.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Atzori, A.S. The Comparison of the Lactation and Milk Yield and Composition of Selected Breeds of Sheep and Goats. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2017, 1, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulwahid Jaber Al-Fayad, M. Evaluation of Different Chemical and Physical Components of Milk in Cows, Buffalos, Sheep, and Goats. Arch. Razi Inst. 2022, 77, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoro, K.; Ferreira, L.M.M.; García, U.; Martínez, A.; Celaya, R. Forage Intake, Digestibility and Performance of Cattle, Horses, Sheep and Goats Grazing Together on an Improved Heathland. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2017, 57, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.S. Estimation of Carcass Composition of Sheep, Goats and Cattle by the Urea Dilution Technique. Pak. J. Nutr. 2010, 9, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M. Body Size and Metabolic Rate. Physiol. Rev. 1947, 27, 511–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaxter, K.L. The Energy Metabolism of Ruminants; Hutchinson Scientific and Technical: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane Emissions from Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, É.; Angers, D.A. Animal Manure Application and Soil Organic Carbon Stocks: A Meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, I.K.; Christensen, B.T. Carbon Sequestration in Soils with Annual Inputs of Maize Biomass and Maize-Derived Animal Manure: Evidence from 13C Abundance. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1643–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A.J.; Topp, C.F.E.; Rees, R.M. Understanding Uncertainty in the Carbon Footprint of Beef Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Qi, L.; Zhao, L. A Global Annual Fractional Tree Cover Dataset during 2000–2021 Generated from Realigned MODIS Seasonal Data. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Natura 2000 Dataset (End 2021 Revision 1). Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/data/dae737fd-7ee1-4b0a-9eb7-1954eec00c65 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Common Database on Designated Areas (CDDA) V2021, Public Version. Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/data/c0c9663b-ea1c-4068-b8b5-533f40539bdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Aryal, D.R.; Morales-Ruiz, D.E.; López-Cruz, S.; Tondopó-Marroquín, C.N.; Lara-Nucamendi, A.; Jiménez-Trujillo, J.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, E.; Betanzos-Simon, J.E.; Casasola-Coto, F.; Martínez-Salinas, A.; et al. Silvopastoral Systems and Remnant Forests Enhance Carbon Storage in Livestock-Dominated Landscapes in Mexico. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay-Smith, T.H.; Burkitt, L.; Reid, J.; López, I.F.; Phillips, C. A Framework for Reviewing Silvopastoralism: A New Zealand Hill Country Case Study. Land 2021, 10, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, T.P. Inflection: Finds the Inflection Point of a Curve. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=inflection (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Wood, S.N. Mgcv: Mixed GAM Computation Vehicle with Automatic Smoothness Estimation. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mgcv (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Funes, I.; Molowny-Horas, R.; Savé, R.; De Herralde, F.; Aranda, X.; Vayreda, J. Carbon Stocks and Changes in Biomass of Mediterranean Woody Crops over a Six-Year Period in NE Spain. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranca, C.; Pedra, F.; Madeira, M. Enhancing Carbon Sequestration in Mediterranean Agroforestry Systems: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Vicente, J.L.; García-Ruiz, R.; Francaviglia, R.; Aguilera, E.; Smith, P. Soil Carbon Sequestration Rates under Mediterranean Woody Crops Using Recommended Management Practices: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 235, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, M.; Rodríguez-González, M.Á.; Paredes, D.; Fernández-Pozo, L. Influence of Mediterranean Shrublands Management on Soil Carbon Sequestration. iScience 2025, 28, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, P.; Delgado, A.; Doblas-Miranda, E.; Berk, B. Carbon Farming, Crop Yield and Biodiversity in Mediterranean Europe: The Dose Makes the Poison? Plant Soil 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Peinado, R.; Bravo-Oviedo, A.; López-Senespleda, E.; Bravo, F.; Del Río, M. Forest Management and Carbon Sequestration in the Mediterranean Region: A Review. For. Syst. 2017, 26, eR04S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Woude, A.M.; Peters, W.; Joetzjer, E.; Lafont, S.; Koren, G.; Ciais, P.; Ramonet, M.; Xu, Y.; Bastos, A.; Botía, S.; et al. Temperature Extremes of 2022 Reduced Carbon Uptake by Forests in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, V.; Martín-Gallego, P.; Julián, F.; Six, J.; Cardinael, R.; Laub, M. Initial Soil Carbon Losses May Offset Decades of Biomass Carbon Accumulation in Mediterranean Afforestation. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 36, e00768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasis, V.P.; Mantzanas, K.; Dini-Papanastasi, O.; Ispikoudis, I. Traditional Agroforestry Systems and Their Evolution in Greece. In Agroforestry in Europe; Rigueiro-Rodróguez, A., McAdam, J., Mosquera-Losada, M.R., Eds.; Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 6, pp. 89–109. ISBN 978-1-4020-8271-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori, S.; Wu, W.; Doelman, J.; Frank, S.; Hristov, J.; Kyle, P.; Sands, R.; Van Zeist, W.-J.; Havlik, P.; Domínguez, I.P.; et al. Land-Based Climate Change Mitigation Measures Can Affect Agricultural Markets and Food Security. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development; Unit A.3 (Policy Performance); European Evaluation Helpdesk for the CAP. Rough Estimate of the Climate Change Mitigation Potential of the CAP Strategic Plans (EU-27) over the 2023–2027 Period. Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/publications/rough-estimates-climate-change-mitigation-potential-cap-strategic-plans-eu-27-over_en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Wolpert, F.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Pulido, F.; Huntsinger, L.; Plieninger, T. Collaborative Agroforestry to Mitigate Wildfires in Extremadura, Spain: Land Manager Motivations and Perceptions of Outcomes, Benefits, and Policy Needs. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Rural Landscape Planning and Forest Management in Tuscany (Italy). Forests 2018, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagella, S.; Caria, M.C.; Seddaiu, G.; Leites, L.; Roggero, P.P. Patchy Landscapes Support More Plant Diversity and Ecosystem Services than Wood Grasslands in Mediterranean Silvopastoral Agroforestry Systems. Agric. Syst. 2020, 185, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlagne, C.; Bézard, M.; Drillet, E.; Larade, A.; Diman, J.-L.; Alexandre, G.; Vinglassalon, A.; Nijnik, M. Stakeholders’ Engagement Platform to Identify Sustainable Pathways for the Development of Multi-Functional Agroforestry in Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Agrofor. Syst. 2023, 97, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakiris, R.; Stara, K.; Kazoglou, Y.; Kakouros, P.; Bousbouras, D.; Dimalexis, A.; Dimopoulos, P.; Fotiadis, G.; Gianniris, I.; Kokkoris, I.P.; et al. Agroforestry and the Climate Crisis: Prioritizing Biodiversity Restoration for Resilient and Productive Mediterranean Landscapes. Forests 2024, 15, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemitzi, A.; Albarakat, R.; Kratouna, F.; Lakshmi, V. Land Cover and Vegetation Carbon Stock Changes in Greece: A 29-Year Assessment Based on CORINE and Landsat Land Cover Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalamenti, E.; Battipaglia, G.; Gristina, L.; Novara, A.; Rühl, J.; Sala, G.; Sapienza, L.; Valentini, R.; La Mantia, T. Carbon Stock Increases up to Old Growth Forest along a Secondary Succession in Mediterranean Island Ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facioni, L.; Burrascano, S.; Chiti, T.; Giarrizzo, E.; Zanini, M.; Blasi, C. Changes in Plant Diversity and Carbon Stocks along a Succession from Semi-Natural Grassland to Submediterranean Quercus cerris L. Woodland in Central Italy. Phytocoenologia 2019, 49, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, A.; Pascual, U.; García-Barrios, L.E.; Mukherjee, N. Drivers to Adopt Agroforestry and Sustainable Land-Use Innovations: A Review and Framework for Policy. Land Use Policy 2025, 151, 107468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J. The CENTURY Model. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models; Powlson, D.S., Smith, P., Smith, J.U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 283–291. ISBN 978-3-642-64692-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schaphoff, S.; Von Bloh, W.; Rammig, A.; Thonicke, K.; Biemans, H.; Forkel, M.; Gerten, D.; Heinke, J.; Jägermeyr, J.; Knauer, J.; et al. LPJmL4—A Dynamic Global Vegetation Model with Managed Land—Part 1: Model Description. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 1343–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Wårlind, D.; Arneth, A.; Hickler, T.; Leadley, P.; Siltberg, J.; Zaehle, S. Implications of Incorporating N Cycling and N Limitations on Primary Production in an Individual-Based Dynamic Vegetation Model. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2027–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, S.; Ju, W.; Chen, J.M.; Ciais, P.; Guo, H.; Pan, Y.; Yu, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. Newly Established Forests Dominated Global Carbon Sequestration Change Induced by Land Cover Conversions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchenwirth, L.; Stümer, W.; Schmidt, T.; Förster, M.; Kleinschmit, B. Large-Scale Mapping of Carbon Stocks in Riparian Forests with Self-Organizing Maps and the k-Nearest-Neighbor Algorithm. Forests 2014, 5, 1635–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M.; DuPont, J.; Somenahally, A.; McLawrence, J.F.; Case, C.L.; Gowda, P.; King, N.; Rouquette, M., Jr.; Yu, R.-Q. Long-Term Grazing and Nitrogen Management Impacted Methane Emission Potential and Soil Microbial Community in Grazing Pastures. Environ. Health 2025, 3, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.B.; Galyean, M.L.; Kallenbach, R.L.; Greenwood, P.L.; Scholljegerdes, E.J. Understanding Intake on Pastures: How, Why, and a Way Forward. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilpakar, C.; Yang, D.; Holbrook, D.L.; Norton, U.; Islam, M.A. Impact of Grazing Duration and Environment on Soil Carbon in Reclaimed Uranium Mines Tailings: A Region Specific Study. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 4474–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Ž.; Romanchuk, Z.; Yashchun, O.; See, L. A Harmonized Data Set of Ruminant Livestock Presence and Grazing Data for the European Union and Neighbouring Countries. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milazzo, F.; Francksen, R.M.; Abdalla, M.; Ravetto Enri, S.; Zavattaro, L.; Pittarello, M.; Hejduk, S.; Newell-Price, P.; Schils, R.L.M.; Smith, P.; et al. An Overview of Permanent Grassland Grazing Management Practices and the Impacts on Principal Soil Quality Indicators. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, B.D.; Dong, X.; Nyren, P.E.; Nyren, A. Effects of Grazing Intensity, Precipitation, and Temperature on Forage Production. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 60, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, H.C.S.; Ashworth, A.J.; O’Brien, P.L.; Thomas, A.L.; Runkle, B.R.K.; Philipp, D. Temperate Silvopastures Provide Greater Ecosystem Services than Conventional Pasture Systems. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, A.; Gwozdz, W. On the Relation between Monocultures and Ecosystem Services in the Global South: A Review. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 278, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecegui, A.; Olaizola, A.M.; Varela, E. Disentangling the Role of Management Practices on Ecosystem Services Delivery in Mediterranean Silvopastoral Systems: Synergies and Trade-Offs through Expert-Based Assessment. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 517, 120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Sandino, C.O.; Barnes, A.P.; Sepúlveda, I.; Garratt, M.P.D.; Thompson, J.; Escobar-Tello, M.P. Examining Factors for the Adoption of Silvopastoral Agroforestry in the Colombian Amazon. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Vargas, C.T.; Morgan, S.; Pantevéz, H.; Gomez, M.; Kennedy, C.M.; Kremen, C. Enablers and Barriers to Adoption of Sustainable Silvopastoral Practices for Livestock Production in Colombia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1600091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammi, I.; Mustajärvi, K.; Rasinmäki, J. Integrating Spatial Valuation of Ecosystem Services into Regional Planning and Development. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziridis, D.; Karmiris, I.; Fotakis, D. Data and Code for “Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean” [Zenodo Data Set]. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17482130 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

| Land Cover Group | CLC Code, Name (% Baseline Cover) |

|---|---|

| Agroforestry | 244, Agroforestry (4.3%) |

| Arable land | 211, Arable non-irrigated (21.2%) |

| Forest | 311, Broadleaf (13.2%); 312, Coniferous (7.8%); 313, Mixed (3.7%) |

| Grasslands | 321, Natural grasslands (5.8%) |

| Mixed agro-systems | 242, Complex cultivation (5.3%); 243, Agri-natural mosaic (4.8%) |

| Pastures | 231, Pastures (1.7%) |

| Shrubby vegetation | 322, Moors/heathland (1.5%); 323, Sclerophyllous (11.5%) |

| Sparsely vegetated | 333, Sparse vegetation (1.3%) |

| Tree plantations | 221, Vineyards (3%); 222, Fruit/berry (2.3%); 223, Olive groves (6%) |

| Woodland-shrub | 324, Woodland-shrub (6.6%) |

| Predictor | Resolution | Rationale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land cover (categorical) | 1 km (modal aggregation) | Represents dominant landscape context affecting grazing and tree cover | CLC 2018 [48] |

| Annual mean temperature (BIO1) | 1 km (from 30″) | Captures climate suitability for woody vegetation and livestock | WorldClim 2.1 [56] |

| Temperature seasonality (BIO4) | 1 km (from 30″) | Reflects climatic extremes influencing vegetation and forage stability | WorldClim 2.1 [56] |

| Annual precipitation (BIO12) | 1 km (from 30″) | Indicates water availability for biomass productivity | WorldClim 2.1 [56] |

| Precipitation seasonality (BIO15) | 1 km (from 30″) | Represents drought stress risk affecting grazing capacity | WorldClim 2.1 [56] |

| Elevation | 1 km (aggregated) | Topographic constraint shaping vegetation structure and microclimate | EU-DEM [57] |

| Slope | 1 km (aggregated) | Limits accessibility for livestock and mechanised management | EU-DEM [57] |

| Aspect | 1 km (categorised) | Influences solar radiation and vegetation patterns | EU-DEM [57] |

| Topsoil organic carbon (TOC) | 1 km (reclassified) | Indicator of soil fertility and biomass retention potential | ESDB [58] |

| Topsoil available water content (TAWC) | 1 km (reclassified) | Determines vegetation resilience under grazing pressure | ESDB [58] |

| Soil texture class (TTEXT) | 1 km (categorical) | Affects root penetration, water retention and tree establishment | ESDB [58] |

| Median population age | 1 km (rasterised) | Proxy for demographic structure influencing labour availability | Eurostat (2022) [59] |

| Population density | 1 km (rasterised) | Indicates human pressure and land-use competition | Eurostat (2022) [60] |

| Employment rate (ages 15–64) | 1 km (rasterised) | Represents socio-economic conditions supporting farming | Eurostat (2022) [61,62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kiziridis, D.A.; Karmiris, I.; Fotakis, D. Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean. Sustainability 2026, 18, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010439

Kiziridis DA, Karmiris I, Fotakis D. Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010439

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiziridis, Diogenis A., Ilias Karmiris, and Dimitrios Fotakis. 2026. "Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010439

APA StyleKiziridis, D. A., Karmiris, I., & Fotakis, D. (2026). Agroforestry Optimisation for Climate Policy: Mapping Silvopastoral Carbon Sequestration Trade-Offs in the Mediterranean. Sustainability, 18(1), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010439