Analysis of the Environmental Impact of Different Olive Grove Systems in Southern Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. The Case Study

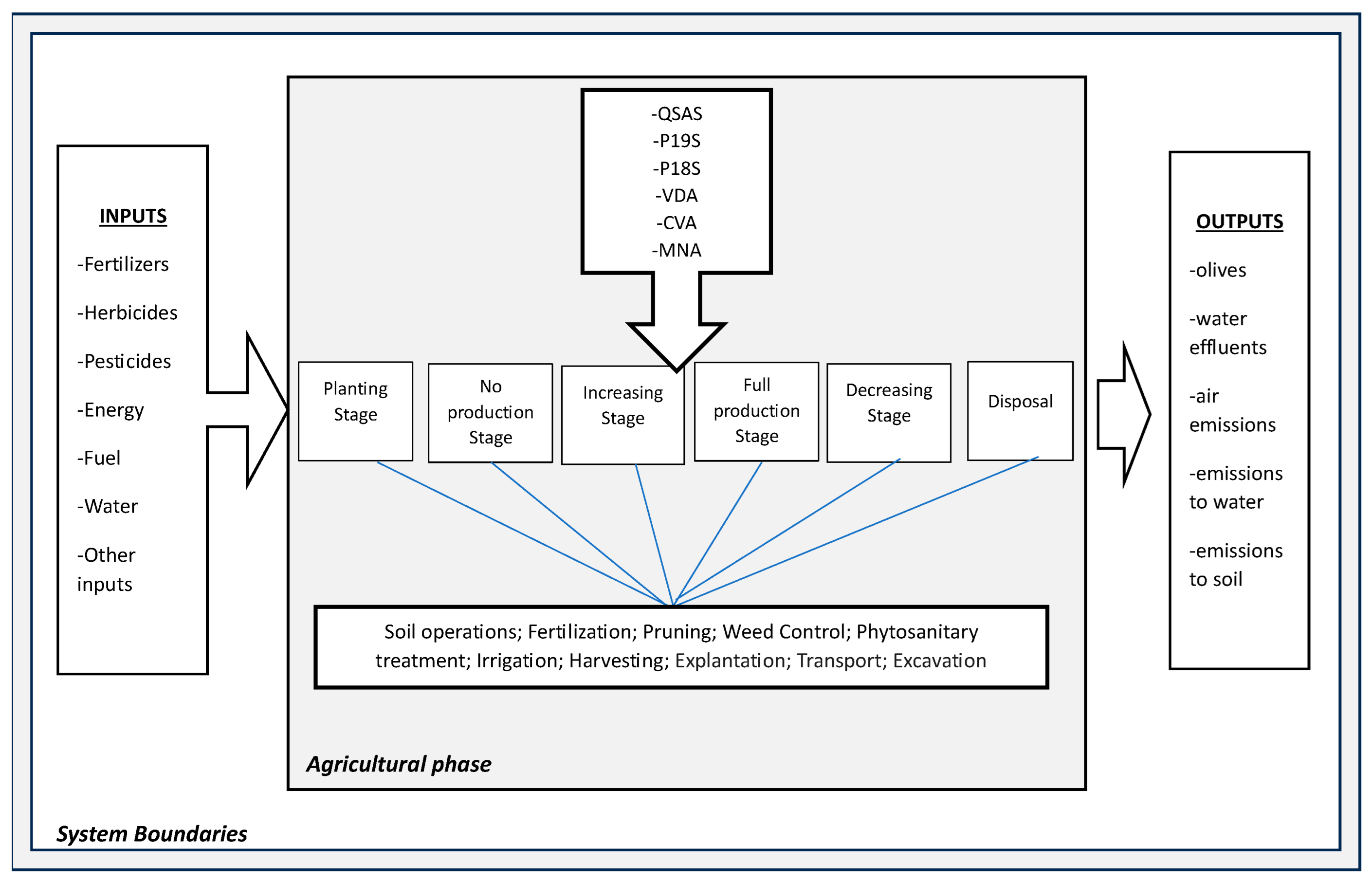

2.2. Goal and Scope

2.3. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) and Impact Assessment (LCIA)

2.4. Limitations

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- INE Instituto Nacional de Estadística/National Statistical Institute. Agricultural Statistics—2021/2022. Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=539491784&DESTAQUESmodo=2 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- IOC International Olive Oil Council. Olive Oil Production Dashboard. 2024. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IOC-Olive-Oil-Dashboard.html#production-1 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sustainolive. Projeto Sustainolive. 2021a. Available online: https://sustainolive.eu/importance-olive-grove-mediterranean-basin/?lang=en (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Campello, F. Sustentabilidade dos Olivais em Portugal: Desafios e Respostas. Principia Editora: Cascais, Portugal. 2022. Available online: https://alfredodasilva150anos.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Sustentabilidade-Olivais-Portugal.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Sales, H.; Figueiredo, F.; Patto, M.C.V.; Nunes, J. Assessing the environmental sustainability of Portuguese olive growing practices from a life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, J.; Santos, P.; Cãno, S.; Caldeira, B.; Dias, P.; Rosario, L. Alentejo: A Liderar a Olivicultura Moderna Internacional. 2019. Available online: https://www.olivumsul.com/_files/ugd/a303d9_5993f29b65054e46a54accff8c90cf7f.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- GPP Análise Setorial do Azeite. 2020. Available online: https://www.gpp.pt/images/PEPAC/Anexo_NDICE_ANLISE_SETORIAL___AZEITE.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- SIAZ -Sistema de Informação do Azeite e Azeitona de Mesa. Campanha 2019-2020. Gabinete de Planeamento, Políticas e Administração Geral (GPP). 2020. Available online: https://www.gpp.pt/index.php/estatisticas-e-analises/siaz-campanha-2019-2020-azeite (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- EC (European Commission). Eurobarometer: Europeans, Agriculture and the CAP. Brussels, Belgium. 2020. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2229 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Silveira, A.; Ferrão, J.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Guimarães, M.H.; Schmidt, L. The sustainability of agricultural intensification in the early 21st century: Insights from the olive oil production in Alentejo (Southern Portugal). In Changing Societies: Legacies and Challenges; Vol. III. The Diverse Worlds of Sustainability; Delicado, A., Domingos, N., de Sousa, L., Eds.; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018; pp. 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Basile, L.; Gagliardi, F.; Riccaboni, A.; Isernia, P. The AGRIFOODMED Delphi Final Report. Trends, Challenges and Policy Options for Water Management, Farming Systems and Agri-Food Value Chains in 2020–2030. PRIMA Annual Work Plan 2018. Siena, Italy. 2019. Available online: http://www.primaitaly.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AGRIFOODMED-Delphi-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Beaufoy, G. EU policies for olive farming—Unsustainable on all counts. 2001. Available online: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/olivefarmingen.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Espadas-Aldana, G.; Vialle, C.; Belaud, J.P.; Vaca-Garcia, C.; Sablayrolles, C. Analysis and trends for life cycle assessment of olive oil production. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Carvalho, M. A agricultura e os sistemas de produção da região Alentejo de Portugal.: Evolução, situação atual e perspectivas. Rev. De Econ. E Agronegócio 2017, 15, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, L.; Barranco, D.; Castro-García, S.; Connor, D.J.; del Campo, M.G.; Rallo, P. High-density olive plantations. Hortic 2013, 41, 303–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gámez, M.; Castro-Rodríguez, J.; Suarez-Rey, E.M. Optimization of olive growing practices in Spain from a life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone, R.; Ioppolo, G. Environmental impacts of olive oil production: A life cycle assessment case study in the province of messina. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joumri, L.E.; Labjar, N.; Dalimi, M.; Harti, S.; Dhiba, D.; El Messaoudi, N.; Bonnefille, S.; El Hajjaji, S. Life cycle assessment (LCA) in the olive oil value chain: A descriptive review. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lobato, L.; López-Sánchez, Y.; Blejman, G.; Jurado, F.; Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Vera, D. Life cycle assessment of the Spanish virgin olive oil production: A case study for Andalusian region. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Sala, S.; Anton, A.; McLaren, S.J.; Saouter, E.; Sonesson, U. The role of life cycle assessment in supporting sustainable agri-food systems: A review of the challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.I.; Falcone, G.; Iofrida, N.; Stillitano, T.; Strano, A.; Gulisano, G. Life Cycle Methodologies to Improve Agri-Food Systems Sustainability. Riv. Di Studi Sulla Sostenibilitá 2015, 1, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone, R.; Cappelletti, G.M.; Malandrino, O.; Mistretta, M.; Neri, E.; Nicoletti, G.M.; Notarnicola, B.; Pattara, C.; Russo, C.; Saija, G. Life cycle assessment in the olive oil sector. In Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-Food Sector; Notarnicola, B., Salomone, R., Petti, L., Renzulli, P., Roma, R., Cerutti, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 57–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, R.S.; Verrastro, V.; Cardone, G.; Bteich, M.R.; Favia, M.; Moretti, M.; Roma, R. Optimization of organic and conventional olive agricultural practices from a Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 70, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, N.; Parker, R.; Henriksson, P.J.G. Environmental nutrition and LCA-Chapter 8. In Environmental Nutrition; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.I.; Iofrida, N.; González de Molina, M.; Spada, E.; Domouso, P.; Falcone, G.; Gulisano, G.; García Ruiz, R. A methodological proposal of the Sustainolive international research project to drive Mediterranean olive ecosystems toward sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1207972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.B.; Parra-López, C.; Elfkih, S.; Suárez-Rey, E.M.; Romero-Gámez, M. Sustainability assessment of traditional, intensive and highly-intensive olive growing systems in Tunisia by integrating Life Cycle and Multicriteria Decision analyses. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.S.V. Análise do ciclo de Vida do Azeite: Caso de Estudo do Azeite de Trás-os-Montes. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico of Bragança, Bragança, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Todde, G.; Murgia, L.; Deligios, P.; Almeida, R.; Carrêlo, I.; Moreira, M.; Pazzona, A.; Ledda, L.; Narvarte, L. Energy and environmental performances of hybrid photovoltaic irrigation systems in Mediterranean intensive and super-intensive olive orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 651, 2514–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.S.; Ferreira, A.F. Techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment of olive and wine industry co-products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainolive. Novel Approaches to Promote the Sustainability of Olive Cultivation in the Mediterranean. D3.2 Database of Experimental Sites According to the STS Concept. 2021b. Available online: https://mel.cgiar.org/projects/sustainolive (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- ISO 14040; 2006 Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Ecoinvent 2023 Ecoinvent Database, V. 3.8. Swiss Centro for Life Cycle Inventories. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecoinvent.org/database/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Nemecek, T.; Bengoa, X.; Lansche, J.; Roesch, A.; Faist-Emmenegger, M.; Rossi, V.; Humbert, S. World Food LCA Database: Methodological Guidelines for the Life Cycle Inventory of Agricultural Products. Version 3.5. Quantis and Agroscope, Lausanne and Zurich, Switzerland. 2019. Available online: https://simapro.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/WFLDB_MethodologicalGuidelines_v3.5.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- PRé Sustainability. SimaPro 9.4: What’s New? 2022. Available online: https://simapro.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SimaPro940WhatIsNew.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- ReCiPe 2016 v1.1 A Harmonized Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level Report I: Characterization. 2017. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2018-11/Report%20ReCiPe_Update_20171002_0.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- De Luca, A.I.; Iofrida, N.; Falcone, G.; Stillitano, T.; Gulisano, G. Olive growing scenarios of soil management: Integrating environmental, economic and social indicators from a life-cycle perspective. Acta Hortic 2018, 1199, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotia, K.; Mehmeti, A.; Tsirogiannis, I.; Nanos, G.; Mamolos, A.P.; Malamos, N.; Barouchas, P.; Todorovic, M. LCA-Based Environmental Performance of Olive Cultivation in Northwestern Greece: From Rainfed to Irrigated through Conventional and Smart Crop Management Practices. Water 2021, 13, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bellido, P.J.; Lopez-Bellido, L.; Fernandez-Garcia, P.; Muñoz-Romero, V.; Lopez-Bellido, F.J. Assessment of Carbon Sequestration and the Carbon Footprint in Olive Groves in Southern Spain. Carbon Manag. 2016, 7, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemecek, T.; Kagi, T. Life Cycle Inventories of Agricultural Production Systems. Ecoinvent-Report n. 15. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263239333_Life_Cycle_Inventories_of_Agricultural_Production_Systems (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- De Luca, A.I.; Falcone, G.; Stillitano, T.; Iofrida, N.; Strano, A.; Gulisano, G. Evaluation of sustainable innovations in olive growing systems: A life cycle sustainability assessment case study in southern Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1187–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Standard | Alternative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAS | P19S | P18S | VDA | CVA | MNA | ||

| GENERAL DATA | Plot size (ha) | 0.5 | 55 | 86 | 8 | 7.16 | 17 |

| Variety | Galega | Cordovil | Arbequina | Galega | Galega | Arbequina | |

| ethod of production | Conventional | Integrated | Conventional | Organic | Integrated | Organic + Biodynamic | |

| Production system | Traditional | High-density | Super-high- density | Traditional | Traditional | Super-high-density | |

| Trees/ha | 60 | 205 | 2050 | 139 | 81 | 1770 | |

| AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES | Fertilization | Fertilization only for the planting stage (Manure) | Foliar treatment with organic nitrogen and NPK + micronutrients; fertigation with NPK; manure only in planting stage | Foliar treatment with organic nitrogen and fertigation with N-P-K + micronutrients; manure only in planting stage | Distribution in the soil of manure and foliar treatment with N-P-K + micronutrients; manure on planting stage | Distribution in the soil of phosphate fertilizer; manure only in planting stage | Distribution in the soil of manure and foliar treatment with N-P-K + micronutrients; manure in planting stage |

| Harvesting | Semi-mechanic with vibrator stick | Mechanic with trunk shakers | Mechanic with olive harvester | Semi-mechanic with vibrator stick | Manual | Mechanical with olive harvester | |

| Irrigation | Rainfed | Irrigated | Irrigated | Rainfed | Rainfed | Irrigated | |

| Phytosanitary control | No pesticides | Six times a year with pesticides (dodine, deltamethrin, copper compounds, difenoconazole, lambdacyhalothrin) | Six times a year with pesticides (Azoxystorbin, dodine, deltamethrin, copper compounds) | Twice a year with Spinosad | No pesticides | Four times a year with copper sulfate | |

| Weed control | No herbicides are used, and control is carried out by the sheep | Four times a year with herbicides (glyphosate, fluroxypyr, and flazasulfuron) | Three times a year with herbicides (glyphosate, fluroxypyr) | Mechanical | Mechanical | Mechanical | |

| SUSTAINABLE TECHNOLOGICAL SOLUTIONS | COCover crops | Cultivated | Spontaneous | Spontaneous | Cultivated | Spontaneous | Spontaneous |

| Livestock integration | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Shredded pruning | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Organic fertilization | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| p | Soil Operations | Fertilization | Weed Control | Phytosanitary | Pruning | Harvesting | Irrigation | Explantation | Transport | Excavation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAS | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | - | - | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | - | - | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X | |

| P19S | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | X | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | X | X | X | - | - | X | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X | |

| P18S | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | X | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | X | X | X | - | - | X | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X | |

| VDA | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X | |

| CVA | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | X | X | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | X | X | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | X | X | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X | |

| MNA | PS | X | X | - | - | - | - | X | - | - | - |

| NPS | X | X | X | X | - | - | X | - | - | - | |

| IS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| FPS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| DS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | |

| D | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | X | X |

| Standard | Alternative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | QSAS | P19S | P18S | VDA | CVA | MNA | Coefficient of Variation | |

| Productivity | t | 2.00 | 8.72 | 15.80 | 2.39 | 1.07 | 16.25 | 90.74% |

| Agricultural Operations | ||||||||

| Soil Management | ||||||||

| Diesel | kg | 6.26 | 18.78 | 12.52 | 11.69 | 12.52 | 25.04 | 45.12% |

| Fertilization | ||||||||

| Organic Nitrogen | kg | 10.92 | 0.84 | 121.22% | ||||

| Inorganic Nitrogen | kg | 0.82 | - | |||||

| N | kg | 169.26 | 195.75 | 2.4 | 63.34 | 84.09% | ||

| P2O5 | kg | 27.24 | 67.01 | 1.2 | 17.86 | 98.65% | ||

| K2O | kg | 57.16 | 206.09 | 2.4 | 32.19 | 121.63% | ||

| Diesel | kg | - | 4.2 | 4.2 | 16.7 | 8.4 | 31.3 | 88.37% |

| Phytosanitary control | ||||||||

| Copper | kg | - | 3.187 | 4.885 | - | - | 4.15 | 92.04% |

| Spinosade | kg | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | |

| Azoxystorbin/Difenoconazole | kg | - | 0.478 | 0.092 | - | - | - | 95.77% |

| Dodine | kg | - | 2.269 | 2.085 | - | - | - | 5.98% |

| Deltamethrin | kg | - | 0.199 | 1.038 | - | - | - | 141.37% |

| Phosmet | kg | - | 1.141 | 0.945 | - | - | - | 141.19% |

| Trifloxystrobin | kg | - | 0.243 | 0.24 | - | - | - | 0.88% |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | kg | - | 0.109 | - | - | - | - | |

| Cresoximemethyl | kg | - | 0.152 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diesel | kg | - | 5.0 | 5.0 | 8.4 | - | 8.4 | 29.30% |

| Weed Control | ||||||||

| Glyphosate | kg | - | 13.632 | 17.674 | - | - | - | 18.26% |

| Fluroxypyr | kg | - | 1.043 | 1.435 | - | - | - | 22.37% |

| Flazasulfuron | kg | - | 0.158 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diesel | kg | - | 4.2 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 4.2 | 18.61% |

| Pruning | ||||||||

| Chainsaw | h | 2.24 | 2.24 | 4.48 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 4.48 | 38.73% |

| Petrol | L | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 38.73% |

| Harvesting | ||||||||

| Electric stick | h | 19 | - | - | 30 | - | - | 31.75% |

| Diesel | kg | - | 66.8 | 20.0 | - | - | 20.5 | 75.14% |

| Irrigation | ||||||||

| Water | m3 | - | 1750 | 2700 | - | - | 2000 | 22.90% |

| Electricity | kWh | - | 0.2 | 0.148 | - | - | 0.2 | 16.44% |

| Disposal | ||||||||

| Explantation | h | 20 | 50 | 60 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 33.7% |

| Transport | kg | 50 | 150 | 300 | 100 | 50 | 300 | 73.16% |

| Excavation | kg | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 0.0% |

| CC | TA | FEU | MEU | WC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg CO2 eq) | (kg SO2 eq) | (kg P eq) | (kg N eq) | (m3) | ||

| Standard | QSAS | 1.16 × 102 | 9.57 × 10−1 | 6.49 × 10−2 | 7.85 × 10−2 | 4.27 × 10−1 |

| P19S | 3.80 × 103 | 5.23 × 101 | 2.68 × 100 | 1.22 × 101 | 1.62 × 103 | |

| P18S | 9.96 × 103 | 1.51 × 102 | 6.60 × 100 | 4.25 × 101 | 2.42 × 103 | |

| Alternative | VDA | 4.25 × 102 | 4.31 × 100 | 1.50 × 10−1 | 4.96 × 10−1 | 4.79 × 100 |

| CVA | 3.47 × 102 | 4.23 × 100 | 2.93 × 10−1 | 8.71 × 10−2 | 4.71 × 100 | |

| MNA | 4.55 × 103 | 6.53 × 101 | 2.77 × 100 | 9.57 × 100 | 1.86 × 103 |

| Olive Tree Plantations | Shoot | Root | Biomass Total | Soil (0–30 cm) | Biomass + Soil Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | 178 | 60 | 238 | 224 | 462 |

| Intensive | 438 | 104 | 542 | 1596 | 2138 |

| Super-intensive | 958 | 224 | 1182 | 3076 | 4258 |

| CC | TA | FEU | MEU | WC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg CO2 eq) | (kg SO2 eq) | (kg P eq) | (kg N eq) | (m3) | ||

| Standard | QSAS | 5.80 × 10−2 | 4.79 × 10−4 | 3.25 × 10−5 | 3.93 × 10−5 | 2.14 × 10−4 |

| P19S | 4.36 × 10−1 | 6.00 × 10−3 | 3.07 × 10−4 | 1.40 × 10−3 | 1.86 × 10−1 | |

| P18S | 6.30 × 10−1 | 9.56 × 10−3 | 4.18 × 10−4 | 2.69 × 10−3 | 1.53 × 10−1 | |

| Alternative | VDA | 1.78 × 10−1 | 1.80 × 10−3 | 6.28 × 10−5 | 2.08 × 10−4 | 2.00 × 10−3 |

| CVA | 3.24 × 10−1 | 3.95 × 10−3 | 2.74 × 10−4 | 8.14 × 10−5 | 4.40 × 10−3 | |

| MNA | 2.80 × 10−1 | 4.02 × 10−3 | 1.70 × 10−4 | 5.89 × 10−4 | 1.14 × 10−1 |

| CC | TA | FEU | MEU | WC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg CO2 eq) | (kg SO2 eq) | (kg P eq) | (kg N eq) | (m3) | |||

| Standard | QSAS | PS | 2.50 × 102 | 1.56 × 101 | 2.54 × 10−2 | 7.21 × 100 | 1.83 × 10−1 |

| NPS | 3.81 × 102 | 6.13 × 100 | 1.32 × 10−1 | 5.19 × 10−3 | 9.81 × 10−1 | ||

| IS | 2.77 × 102 | 4.46 × 100 | 9.60 × 10−2 | 3.77 × 10−3 | 7.13 × 10−1 | ||

| FPS | 8.29 × 103 | 5.30 × 101 | 4.73 × 100 | 4.19 × 10−1 | 3.06 × 101 | ||

| DS | 2.21 × 103 | 1.57 × 101 | 1.47 × 100 | 1.36 × 10−1 | 9.76 × 100 | ||

| D | 2.12 × 102 | 7.85 × 10−1 | 3.38 × 10−2 | 7.23 × 10−2 | 4.35 × 10−1 | ||

| P19S | PS | 9.97 × 102 | 2.79 × 101 | 3.39 × 10−1 | 1.29 × 101 | 4.61 × 102 | |

| NPS | 8.43 × 103 | 1.37 × 102 | 4.93 × 100 | 3.86 × 101 | 2.38 × 103 | ||

| IS | 1.91 × 104 | 2.68 × 102 | 1.38 × 101 | 6.25 × 101 | 8.07 × 103 | ||

| FPS | 2.87 × 105 | 3.91 × 103 | 2.03 × 102 | 8.99 × 102 | 1.25 × 105 | ||

| DS | 6.40 × 104 | 8.84 × 102 | 4.59 × 101 | 2.04 × 102 | 2.68 × 104 | ||

| D | 5.90 × 102 | 2.29 × 100 | 9.40 × 10−2 | 1.81 × 10−1 | 1.14 × 100 | ||

| P18S | PS | 1.36 × 103 | 3.56 × 101 | 6.60 × 10−1 | 1.61 × 101 | 6.87 × 102 | |

| NPS | 2.75 × 104 | 4.39 × 102 | 1.86 × 101 | 1.27 × 102 | 6.40 × 103 | ||

| IS | 4.52 × 104 | 6.51 × 102 | 3.19 × 101 | 1.78 × 102 | 2.08 × 104 | ||

| FPS | 7.32 × 105 | 1.11 × 104 | 4.85 × 102 | 3.15 × 103 | 1.67 × 105 | ||

| DS | 1.87 × 105 | 2.81 × 103 | 1.24 × 102 | 7.83 × 102 | 4.66 × 104 | ||

| D | 2.59 × 103 | 1.31 × 101 | 4.01 × 10−1 | 2.23 × 10−1 | 2.95 × 100 | ||

| Alternative | VDA | PS | 4.20 × 102 | 1.35 × 101 | 2.58 × 10−1 | 7.22 × 100 | 1.63 × 100 |

| NPS | 1.80 × 103 | 2.78 × 101 | 5.73 × 10−1 | 4.02 × 100 | 2.04 × 101 | ||

| IS | 1.94 × 103 | 2.44 × 101 | 5.42 × 10−1 | 3.36 × 100 | 2.56 × 101 | ||

| FPS | 2.88 × 104 | 2.75 × 102 | 1.03 × 101 | 2.63 × 101 | 3.24 × 102 | ||

| DS | 9.17 × 103 | 8.92 × 101 | 3.33 × 100 | 8.61 × 100 | 1.06 × 102 | ||

| D | 4.43 × 102 | 1.68 × 100 | 7.05 × 10−2 | 1.45 × 10−1 | 8.86 × 10−1 | ||

| CVA | PS | 3.09 × 102 | 1.33 × 101 | 7.83 × 10−2 | 7.22 × 100 | 1.19 × 100 | |

| NPS | 1.81 × 103 | 2.49 × 101 | 1.21 × 100 | 4.57 × 10−2 | 1.92 × 101 | ||

| IS | 2.12 × 103 | 2.60 × 101 | 1.64 × 100 | 5.90 × 10−2 | 2.91 × 101 | ||

| FPS | 2.46 × 104 | 2.92 × 102 | 2.12 × 101 | 1.03 × 100 | 3.41 × 102 | ||

| DS | 5.64 × 103 | 6.58 × 101 | 5.14 × 100 | 2.72 × 10−1 | 8.01 × 101 | ||

| D | 2.69 × 102 | 1.01 × 100 | 4.27 × 10−2 | 9.04 × 10−2 | 5.45 × 10−1 | ||

| MNA | PS | 2.53 × 103 | 2.75 × 101 | 3.01 × 100 | 1.09 × 101 | 1.88 × 101 | |

| NPS | 1.18 × 104 | 1.71 × 102 | 7.06 × 100 | 2.05 × 101 | 4.71 × 103 | ||

| IS | 2.04 × 104 | 2.69 × 102 | 1.31 × 101 | 2.87 × 101 | 1.58 × 104 | ||

| FPS | 3.70 × 105 | 5.41 × 103 | 2.24 × 102 | 8.34 × 102 | 1.31 × 105 | ||

| DS | 4.80 × 104 | 6.42 × 102 | 3.01 × 101 | 6.31 × 101 | 3.47 × 104 | ||

| D | 1.68 × 103 | 8.05 × 100 | 2.62 × 10−1 | 2.20 × 10−1 | 2.20 × 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hermeto de Pádua Souza, R.; Fragoso, R.; Marques, C.; Falcone, G.; De Luca, A.I. Analysis of the Environmental Impact of Different Olive Grove Systems in Southern Portugal. Sustainability 2026, 18, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010430

Hermeto de Pádua Souza R, Fragoso R, Marques C, Falcone G, De Luca AI. Analysis of the Environmental Impact of Different Olive Grove Systems in Southern Portugal. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010430

Chicago/Turabian StyleHermeto de Pádua Souza, Rachel, Rui Fragoso, Carlos Marques, Giacomo Falcone, and Anna Irene De Luca. 2026. "Analysis of the Environmental Impact of Different Olive Grove Systems in Southern Portugal" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010430

APA StyleHermeto de Pádua Souza, R., Fragoso, R., Marques, C., Falcone, G., & De Luca, A. I. (2026). Analysis of the Environmental Impact of Different Olive Grove Systems in Southern Portugal. Sustainability, 18(1), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010430