A Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in the Shorelines of Urban Lakes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Abundance of Microplastics

3.2. Morphological Characteristics of Microplastics

3.3. Color Characteristics of Microplastics

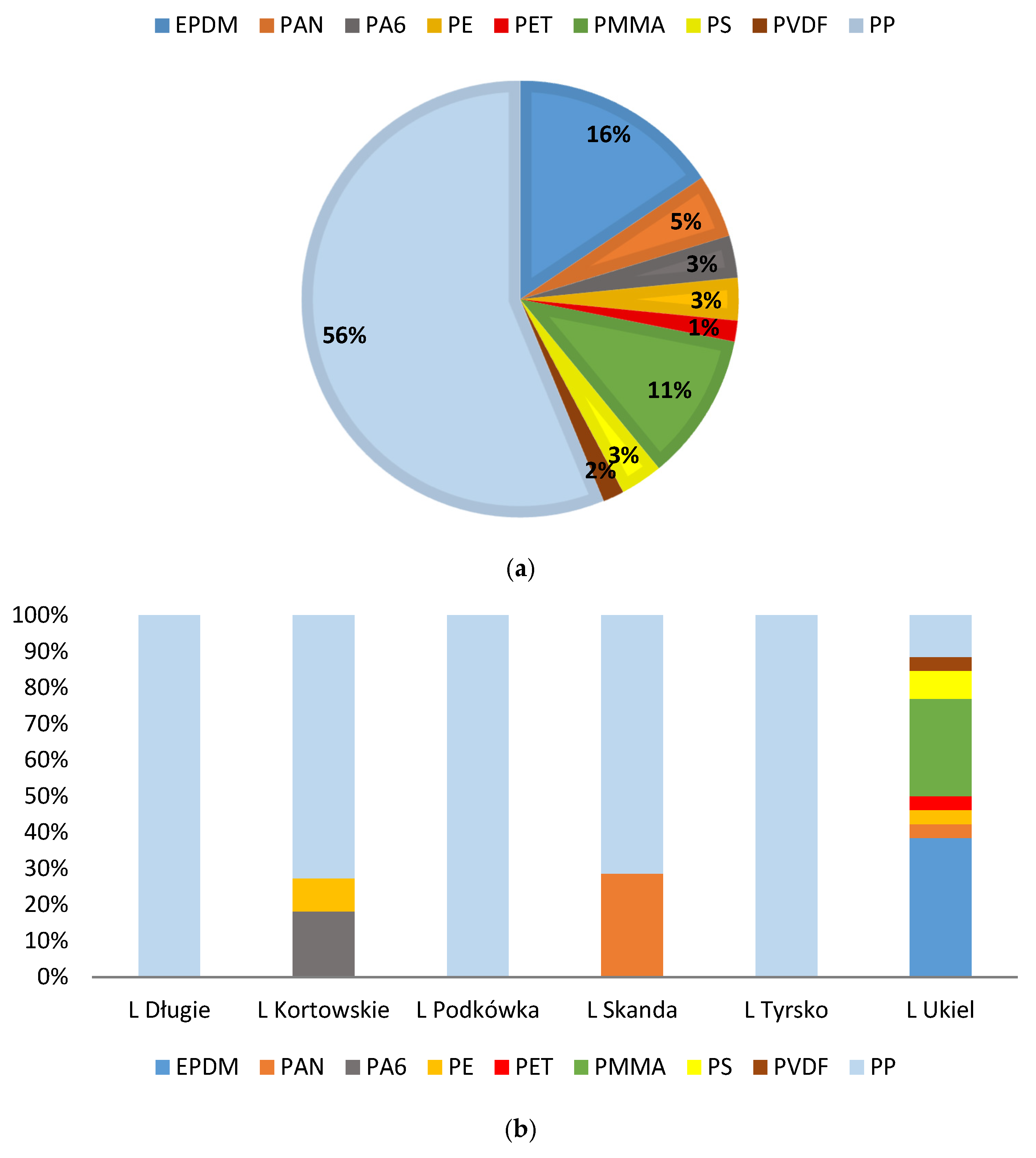

3.4. Composition of Microplastics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpenter, E.J.; Anderson, S.J.; Harvey, G.R.; Miklas, H.P.; Peck, B.B. Polystyrene spherules in coastal waters. Science 1972, 178, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thushari, G.G.N.; Senevirathna, J.D.M. Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbyszewski, M.; Corcoran, P.L. Distribution and Degradation of Fresh Water Plastic Particles Along the Beaches of Lake Huron, Canada. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 220, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, F.; Corbaz, M.; Baecher, H.; De Alencastro, L.F. Pollution due to plastics and microplastics in lake Geneva and in the Mediterranean sea. Arch. Sci. 2012, 65, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dusaucy, J.; Gateuille, D.; Perrette, Y.; Naffrechoux, E. Microplastic pollution of worldwide lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egessa, R.; Nankabirwa, A.; Ocaya, H.; Pabire, W.G. Microplastic pollution in surface water of Lake Victoria. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Velazquez, D.; Edo, C.; Carretero, O.; Gago, J.; Baron-Sola, A.; Hernandez, L.E.; Yousef, I.; Quesada, A.; Leganes, F.; et al. Fibers spreading worldwide: Microplastics and other anthropogenic litter in an Arctic freshwater lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterich, F.; Lo Giudice, A.; Azzaro, M. A plastic world: A review of microplastic pollution in the freshwaters of the Earth’s poles. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete Velasco, A.; de Rard, L.; Blois, W.; Lebrun, D.; Lebrun, F.; Pothe, F.; Stoll, S. Microplastic and fibre contamination in a remote mountain lake in Switzerland. Water 2020, 12, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avignon, G.; Gregory-Eaves, I.; Ricciardi, A. Microplastics in lakes and rivers: An issue of emerging significance to limnology. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowszys, M. Microplastics in the waters of European lakes and their potential effect on food webs: A review. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2022, 37, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Liao, H.; Yang, F.; Sun, F.; Guo, Y.; Yang, H.; Feng, D.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q. Review of microplastics in lakes: Sources, distribution characteristics, and environmental effects. Carbon Res. 2023, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.J.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Jung, S.W.; Shim, W.J. Combined Effects of UV Exposure Duration and Mechanical Abrasion on Microplastic Fragmentation by Polymer Type. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4368–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Falahudin, D.; Peeters, E.T.H.M.; Koelmans, A.A. Microplastic effect thresholds for freshwater benthic macroinvertebrates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2278–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, F.M.; Tilley, R.M.; Tyler, C.R.; Ormerod, S.J. Microplastic ingestion by riverine macroinvertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwesigye, E.; Nnadozie, C.F.; Akamagwuna, F.C.; Noundou, X.S.; Nyakairu, G.W.; Odume, O.N. Microplastics as vectors of chemical contaminants and biological agents in freshwater ecosystems: Current knowledge status and future perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Pedrouzo-Rodríguez, A.; Verdú, I.; Leganés, F.; Marco, E.; Rosal, R.; Fernández-Piñas, F. Microplastics as vectors of the antibiotics azithromycin and clarithromycin: Effects towards freshwater microalgae. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 128824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.R.; Hoellein, T.J.; London, M.G.; Hittie, J.; Scott, J.W.; Kelly, J.J. Microplastic in surface waters of urban rivers: Concentration, sources, and associated bacterial assemblages. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbeckmann, S.; Kreikemeyer, B.; Labrenz, M. Environmental factors support the formation of specific bacterial assemblages on microplastics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Pan, J.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Bartlam, M.; Wang, Y. Selective Enrichment of Bacterial Pathogens by Microplastic Biofilm. Water Res. 2019, 165, 114979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Almuhtaram, H.; McKie, M.J.; Andrews, R.C. Assessment of Biofilm Growth on Microplastics in Freshwaters Using a Passive Flow-Through System. Toxics 2023, 11, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhof, H.K.; Ivleva, N.P.; Schmid, J.; Niessner, R.; Laforsch, C. Contamination of beach sediments of a subalpine lake with microplastic particles. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faure, F.; Demars, C.; Wieser, O.; Kunz, M.; De Alencastro, L.F. Plastic pollution in Swiss surface waters: Nature and concentrations, interaction with pollutants. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.K.; Paglialonga, L.; Czech, E.; Tamminga, M. Microplastic pollution in lakes and lake shoreline sediments—A case study on Lake Bolsena and Lake Chiusi (central Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengstmann, E.; Weil, E.; Wallbott, P.C.; Tamminga, M.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastics in lakeshore and lakebed sediments–external influences and temporal and spatial variabilities of concentrations. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malla-Pradhan, R.; Phoungthong, K.; Suwunwong, T.; Joshi, T.P.; Pradhan, B.L. Microplastic pollution in lakeshore sediments: The first report on abundance and composition of Phewa Lake, Nepal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 70065–70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanentzap, A.J.; Cottingham, S.; Fonvielle, J.; Riley, I.; Walker, L.M.; WooDman, S.G.; Kon-Tou, D.; Pichler, C.M.; Reisner, E.; Leberton, L. Microplastics and anthropogenic fiber concentrations in lakes reflect surrounding land use. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. What Do We Know About Plastic Pollution in Coastal/Marine Tourism? Documenting Its Present Research Status from 1999 to 2022. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231211706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, P.; Prearo, M.; Pizzul, E.; Elia, A.C.; Renzi, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Barceló, D. High-mountain lakes as indicators of microplastic pollution: Current and future perspectives. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplast. 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Tauseef, S.M.; Sharma, M. Microplastic pollution in Himalayan lakes: Assessment, risks, and sustainable remediation strategies. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2025, 25, 2144–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorter, C.; Kutser, T.; Seekell, D.A.; Tranvik, L.J. A global inventory of lakes based on high-resolution satellite imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 6396–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossow, K.; Gawrońska, H.; Mientki, C.Z.; Łopata, M.; Wiśniewski, G. Jeziora Olsztyna Stan Troficzny, Zagrożenia; Wyd. Edycja sc.: Olsztyn, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments; NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R-R-48; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besley, A.; Vijver, G.M.; Behrens, P.; Bosker, T. A standardized method for sampling and extraction methods for quantifying microplastics in beach sand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 114, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Monitoring Plastics in Rivers and Lakes: Guidelines for the Harmonization of Methodologies; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yonkos, L.T.; Friedel, E.A.; Perez-Reyes, A.C.; Ghosal, S.; Arthur, C. Microplastics in four estuarine rivers in the Chesapeake Bay, U.S.A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14195–14202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusher, A.L.; Mchugh, M.; Thompson, R.C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 67, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jian, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, W. Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in the sediments of Poyang Lake, China. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 79, 1868–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Du, C.; Wu, L.; Long, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yin, Q.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Microplastics in Sediment and Surface Water of West Dongting Lake and South Dongting Lake: Abundance, Source and Composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, R.; Turner, S.D.; Rose, N.L. Microplastics in the sediments of a UK urban lake. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbyszewski, M.; Corcoran, P.L.; Hockin, A. Comparison of the distribution and degradation of plastic debris along shorelines of the Great Lakes, North America. J. Great Lakes Res. 2014, 40, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, W.; Stasińska, E.; Żmijewska, A.; Więcko, A.; Zieliński, P. Litter per liter—Lakes’ morphology and shoreline urbanization index as factors of microplastic pollution: Study of 30 lakes in NE Poland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retama, I.; Jonathan, M.P.; Shruti, V.C.; Velumani, S.; Sarkar, S.K.; Roy, P.D.; Rodríguez-Espinosa, P.F. Microplastics in tourist beaches of Huatulco Bay, Pacific coast of southern Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şener, İ.; Yabanlı, M. Macro- and microplastic abundance from recreational beaches along the South Aegean Sea (Türkiye). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhong, C.; Wang, T.; Zou, X. Assessment on the pollution level and risk of microplastics on bathing beaches: A case study of Liandao, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogowska, W.; Skorbiłowicz, E.; Skorbiłowicz, M.; Trybułowski, Ł. Microplastics in coastal sediments of Ełckie Lake (Poland). Stud. Quat. 2021, 38, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.R.; Imbert, A.; Parker, B.; Euphrasie, A. Microplastic in angling baits as a cryptic source of contamination in European freshwaters. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.S.; Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Potential microplastic release from beached fishing gear in Great Britain’s region of highest fishing litter density. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakanthan, K.; Fraser, M.P.; Herckes, P. Recreational activities as a major source of microplastics in aquatic environments. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplast. 2024, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, F.; Cocca, M.; Avella, M.; Thompson, R.C. Microfiber release to water, via laundering, and to air, via everyday use: A comparison between polyester clothing with differing textile parameters. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 54, 3288–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Liu, C. Microplastics release from face masks: Characteristics, influential factors, and potential risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Torre, G.E.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C.; Dobaradaran, S.; Spitz, J.; Nabipour, I.; Keshtkar, M.; Akhbarizadeh, R.; Tangestani, M.; Abedi, D.; Javanfekr, F. Release of phthalate esters (PAEs) and microplastics (MPs) from face masks and gloves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.S.; Not, C. Variations in the spatial distribution of expanded polystyrene marine debris: Are Asian’s coastlines more affected? Environ. Adv. 2023, 11, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, M. Tiny, shiny, and colorful microplastics: Are regular glitters a significant source of microplastics? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataram, A.; Ismail, A.F.; Mahmod, D.S.A.; Matsuura, T. Characterization and mechanical properties of polyacrylonitrile/silica composite fibers prepared via dry-jet wet spinning process. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arturo, I.A.; Corcoran, P.L. Categorization of plastic debris on sixty-six beaches of the Laurentian Great Lakes, North America. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Dixon, S.J. Microplastics: An introduction to environmental transport processes. WIREs Water 2018, 5, e1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lake | Recreational Use of a Lake | Recreational Development of the Lake | Recreational Use of a Beach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Długie | angling | developed walking and cycling paths | shoreline recreation, angling |

| Kortowskie | angling, boating, bathing | walking paths | bathing area, shoreline recreation, angling, cultural events |

| Podkówka | none | none | angling |

| Skanda | angling, boating, bathing | beach volleyball court, pier, developed walking and cycling paths, car park | guarded bathing area, angling, shoreline recreation |

| Tyrsko | bathing, diving, angling | none | bathing area, angling |

| Ukiel | angling, boating, sailing, bathing, diving, windsurfing and other water sports | developed walking and cycling paths, beach courts, pier, playgrounds, gastronomy, water sports equipment hire, marina, car park | guarded bathing area, shoreline recreation, recreational and sport events, cultural events |

| Lake | Area (ha) | Maximal Depth (m) | Mean Depth (m) | Catchment Area (ha) | Dominant Land Cover of the Catchment Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Długie | 26.8 | 17.3 | 5.3 | 136.8 | forests 58.0, development 32.0 |

| Kortowskie | 89.7 | 17.2 | 5.9 | 102.1 | wasteland 30.0, horticultural land 26.5, forests 19.3 |

| Podkówka | 6.9 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 25.6 | wasteland 68.8, forests 23.0 |

| Skanda | 51.5 | 12.0 | 5.8 | 71.8 | forests 52.9, agricultural land 33.7 |

| Tyrsko | 18.6 | 30.4 | 9.6 | 68.0 | wasteland 41.9, forests 36.2 |

| Ukiel | 412.0 | 43.0 | 10.6 | 1675.0 | forests 62.7, wasteland 21.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bowszys, M. A Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in the Shorelines of Urban Lakes. Sustainability 2026, 18, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010361

Bowszys M. A Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in the Shorelines of Urban Lakes. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010361

Chicago/Turabian StyleBowszys, Magdalena. 2026. "A Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in the Shorelines of Urban Lakes" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010361

APA StyleBowszys, M. (2026). A Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in the Shorelines of Urban Lakes. Sustainability, 18(1), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010361