1. Introduction

Rapid technological breakthroughs and rising global uncertainty have been driving an unparalleled rate of digital transformation of supply chains, especially in the e-commerce industry [

1]. The incorporation of digital technologies and strategies targeted at improving supply chain operations’ resilience, agility, and sustainability is what defines this shift. Businesses are better prepared to handle the intricacies of contemporary business settings, where interruptions have increased in frequency and severity, as they embrace digital supply chain management techniques [

2]. The necessity for strong and resilient supply chains that can tolerate and bounce back from a variety of difficulties is highlighted by these disruptions, which range from worldwide pandemics to technological revolutions [

3].

As businesses realize how crucial it is to preserve operational stability and continuity, the idea of supply chain resilience has attracted a lot of attention lately. In this sense, a supply chain’s resilience is its capacity to withstand shocks, adjust to shifting circumstances, and bounce back quickly from interruptions [

4]. The speed at which technology is developing, especially in the field of information technology (IT), has drastically changed how businesses handle supply chain management. In order to survive in the digital age, supply chain operations must now include IT into every aspect of their operations [

5]. By encouraging increased connectedness and integration across different divisions within a business, this process known as supply chain digitization not only improves efficiency but also simplifies processes.

A key component of contemporary supply chain management is data-driven decision-making, which helps businesses streamline processes and boost productivity [

6]. Effective supply chain integration requires high-quality data because it enables predictive analytics, real-time monitoring, and better decision-making [

7]. These skills are especially useful in the context of e-commerce, where a company’s capacity to satisfy client needs and preserve competitive advantage may be greatly impacted by the speed and precision of decision-making [

8].

IT-driven supply chain digitalization is essential for increasing organizational agility in addition to efficiency [

9]. The capacity of a company to react swiftly and efficiently to shifting consumer demands and market situations is referred to as agility [

10]. Agility is crucial for maintaining competitive advantage in the fast-paced corporate world of today, when customer preferences and market dynamics can change drastically. The basis for the agility needed by contemporary firms has been established by the development of IT and its incorporation into supply chain management [

11]. IT gives businesses the ability to quickly adapt their supply chain operations by facilitating automation, real-time data access, and predictive analytics. This improves their capacity to react to market circumstances and disruptions [

12].

IT integration into supply chains has important environmental implications in addition to efficiency and agility. Organizations are looking for more methods to link their operations with sustainable development goals as the emphasis on environmental and social responsibility grows on a global scale [

13]. Modern technology is essential to sustainable production processes and has changed business sustainability programs. Technologies like blockchain, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are completely changing how businesses handle supply chain sustainability [

14]. The IoT, for example, makes it possible to measure and lower an organization’s carbon footprint by enabling real-time environmental performance monitoring. AI-powered analytics may reduce waste, maximize resource utilization, and improve supply chain operations’ overall effectiveness [

6]. However, blockchain technology offers traceability and transparency across the supply chain [

7].

Creating sustainable supply chains that support social and environmental well-being is another goal of integrating technology-driven solutions into supply networks, in addition to increasing operational efficiency [

15]. Supply chains that preserve resources, reduce adverse effects on the environment, and improve community well-being are considered sustainable. Organizations may develop more environmentally friendly supply chains that are both more responsible and efficient by incorporating digital technology [

16]. For example, technology-driven manufacturing processes may cut inventories, lower energy usage, and decrease emissions, all of which contribute to a more sustainable supply chain. Digital technology may also mean that supply chains follow environmental and ethical norms by improving traceability and transparency, which encourages social responsibility [

1,

7].

Even though incorporating digital technology into supply chain management has many advantages, there are obstacles in the way of real resilience and sustainability [

17]. For many firms, it is still difficult to integrate sustainability and resilience into supply chain operations. Although digital transformation has the potential to improve supply chain performance, a number of barriers frequently prevent its adoption, such as organizational opposition, technological complexity, and the requirement for significant expenditures in new technology [

18]. Furthermore, firms may find it difficult to stay abreast of the most recent developments and their consequences for supply chain management due to the quick speed of technological change [

19].

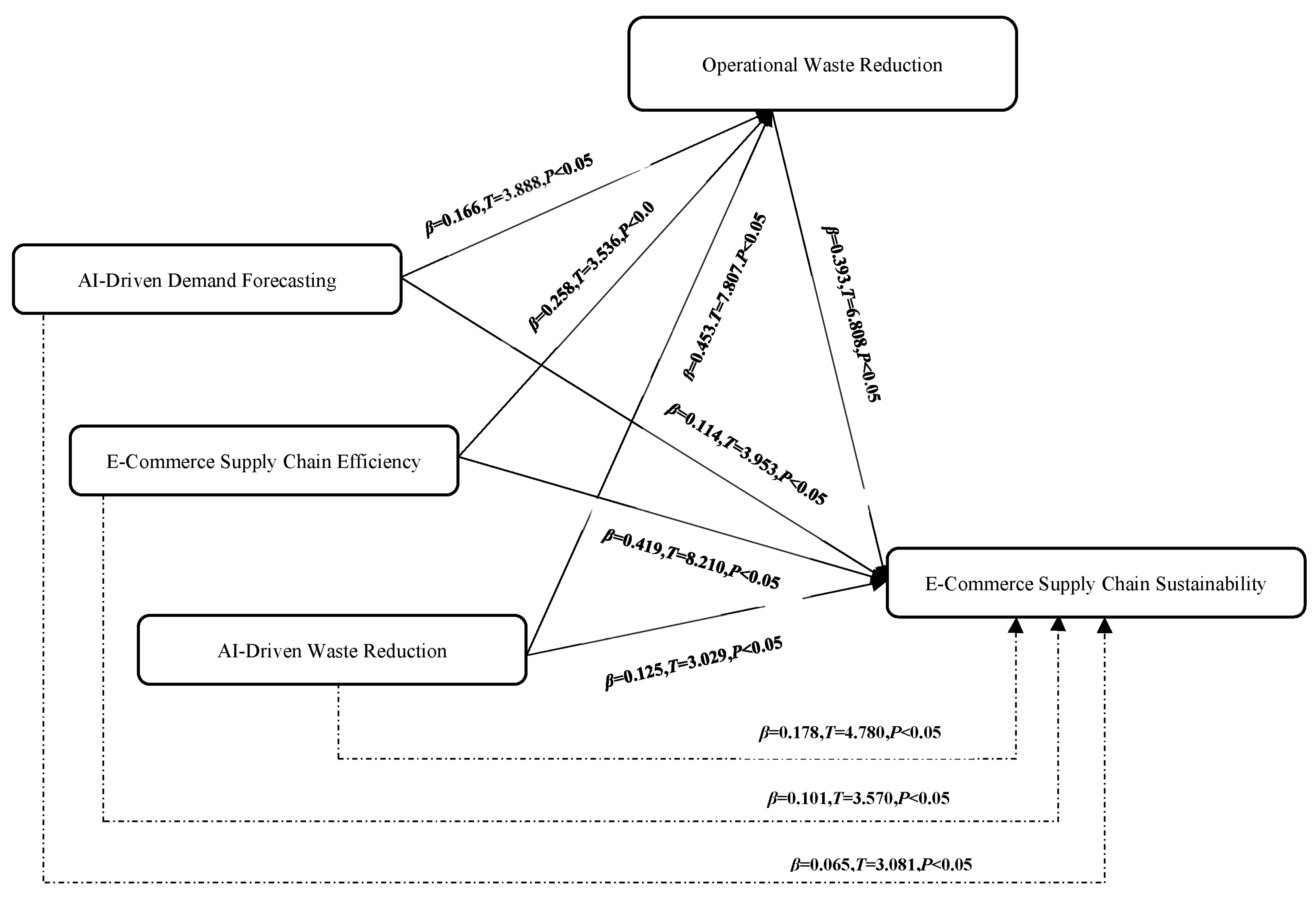

This study clarifies its theoretical novelty by specifying that the main contribution is an integrated framework that links AI practices to sustainability through the mediating mechanism of operational waste reduction, particularly in data-rich e-commerce settings. Unlike prior work that treats AI, resilience, and green/sustainable outcomes as parallel streams, we theorize and empirically test waste reduction as the causal pathway through which granular AI practices, e.g., demand sensing, anomaly detection, and AI-supported replenishment, translate into environmental and resilience gains. This moves the literature beyond generic “digitalization” proxies and applied PLS-SEM confirmations by offering a mechanism-oriented explanation with clear boundary conditions, e.g., high data quality, rapid feedback loops, and robust algorithmic governance. In short, this involves an integrated framework centering waste-reduction mediation, the concrete operationalization of AI-linked routines to process-level metrics, and the explicit positioning in the e-commerce context where these effects are most salient. Additionally, we delineate testable propositions that differentiate direct AI-to-performance effects from indirect, waste-mediated effects, clarifying where mediation should be partial versus full. We also articulate falsifiable contingencies such as demand volatility and data sparsity that bound the theory’s scope and guide future comparative tests across non-e-commerce contexts.

The research addresses several key questions: How does AI-driven demand forecasting impact e-commerce supply chain efficiency? To what extent does improved supply chain efficiency reduce operational waste? How do AI-driven waste reduction practices enhance the overall sustainability of e-commerce supply chains? What is the mediating role of waste reduction in the relationship between AI-driven demand forecasting and supply chain efficiency? And how do AI-driven sustainability practices affect the resilience of e-commerce supply chains? The research seeks to answer these questions in order to accomplish a number of important goals, including assessing how AI-driven demand forecasting affects supply chain efficiency, examining the relationship between efficiency and waste reduction, evaluating how AI-driven waste reduction contributes to sustainability, examining how waste reduction mediates the relationship between demand forecasting and supply chain efficiency, and figuring out how AI-driven sustainability practices affect supply chain resilience.

This study contributes to the e-commerce and AI literature by offering a comprehensive analysis of how AI-driven demand forecasting and waste reduction strategies simultaneously improve supply chain efficiency, resilience, and sustainability. While much of the existing research focuses on one of these elements at a time, this study uniquely integrates both supply chain resilience and environmental sustainability with AI adoption, providing a more holistic approach to supply chain management.

The findings lie in its dual focus on both operational and environmental outcomes. It highlights that operational waste reduction, mediated by AI applications, can serve as a critical lever for enhancing supply chain resilience. This dual contribution to both operational excellence and sustainability goals sets the study apart from prior research. Furthermore, this study offers practical recommendations for e-commerce businesses seeking to integrate AI into their operations. The findings emphasize the importance of AI not only in optimizing efficiency but also in enabling firms to meet their environmental sustainability targets, which is an emerging concern in today’s business landscape.

3. Data Collection and Instrumentation

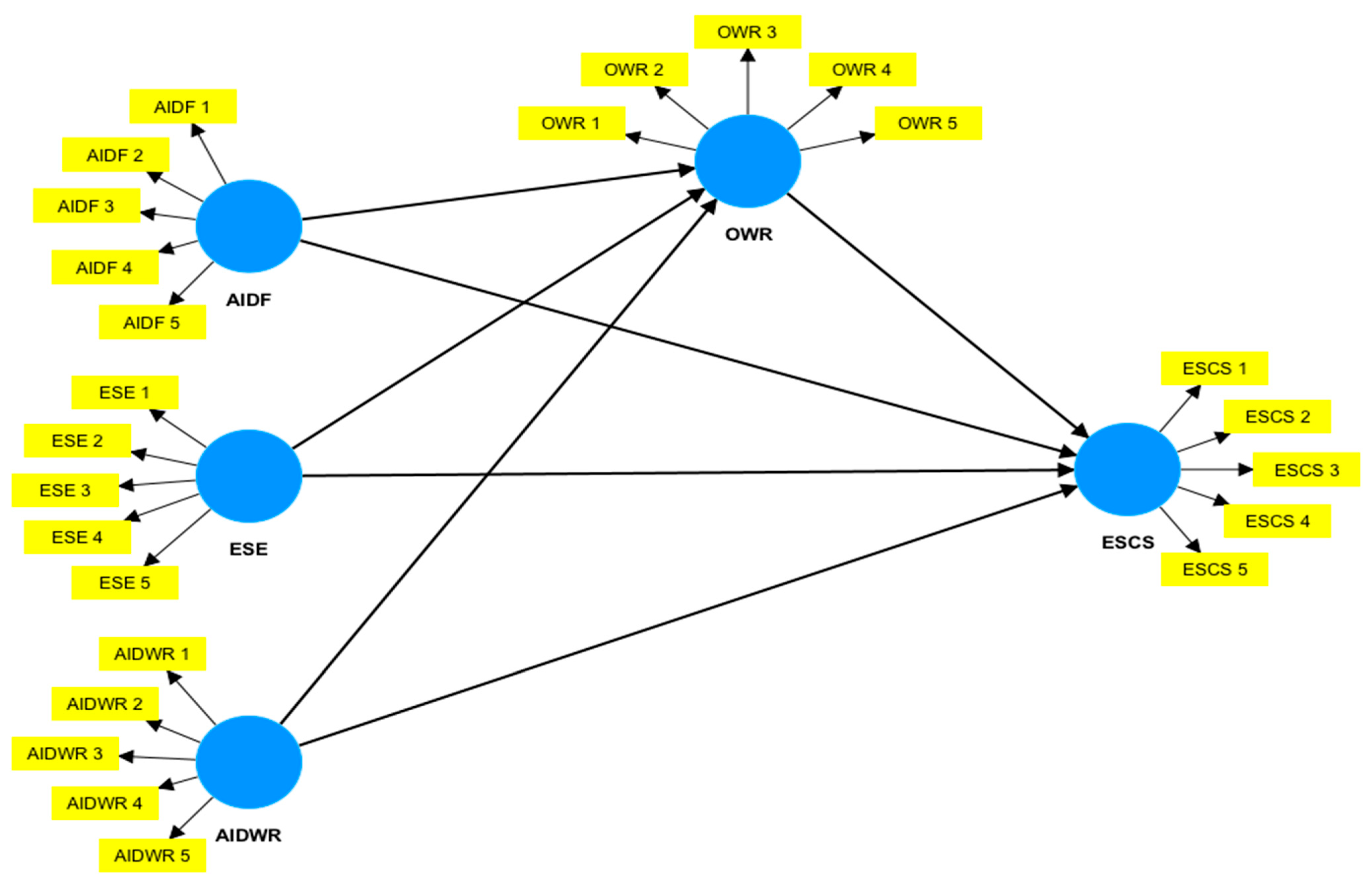

In order to overcome the limitations of traditional CBSEM for our theoretical analysis, the study employed PLS-SEM with bootstrapping (5000 replications) to predict statistical models [

79]. In this examination, the questionnaire instrument and survey research technique were applied. In Bangladesh, several firms operate business on various online platforms, and our study’s target demographic consists of managers at all levels. A questionnaire that was given to 570 management staff members who were chosen at random was used to gather data; 31 responses were eliminated following data screening because they contained missing or insufficient information. Therefore, the study’s sample size is 539. The sample size requirement is based on the recommendations of several scholars who claimed that a sample size of 150 is adequate, according to [

80].

In determining the required sample size for the survey, a standard formula for estimating a population proportion was employed (Formula (1)):

The parameters for this calculation were selected to ensure a robust and conservative estimate. The critical value

z = 1.96 corresponds to the 95% confidence level from the standard normal distribution. The proportion

p = 0.50 (50%) represents the assumed maximum variance scenario for “success,” with its complement

q = 1 −

p = 0.50. This value of

p = 0.50 is intentionally used as it yields the largest possible product,

p ×

q, thereby resulting in the maximum required sample size and erring on the side of caution. The margin of error d was set as 0.075, derived by applying the stated allowable relative error of 15% to the proportion pp (i.e., 0.15 × 0.50) [

81].

This combination of parameters ensures that the calculated sample size is sufficient to estimate the true population proportion with high confidence and precision, given the study’s findings. Our sample size, 539, exceeds the number 171 according to the formula; as a result, this study’s sample size is large enough for making estimations of the variables.

Before the entire survey was sent, a pilot test and many bias analyses were carried out to guarantee data validity and reliability. Both academic researchers and business experts participated in the pilot test, which sought to assess the survey’s content validity, reliability, and clarity [

82]. Five supply chain managers and seven academics, three from Bangladesh and four from China, pretested the questionnaire before it was sent to make sure it was understandable and clear. This focus group-style pretest offered comprehensive input on the quality of the questions, phrasing, and instructions. Managers from senior, medium, and lower management levels from various firms participated. The questionnaire’s reliability was evaluated in a follow-up pilot test with 39 participants, which made sure that every item was understandable, pertinent, and appropriately captured the targeted components [

83]. This stage’s feedback resulted in wording changes and the removal of certain elements to improve clarity. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to verify construct validity and dependability, showing findings that were within reasonable bounds. Before moving forward with the full-scale study, this procedure made sure the survey instrument was reliable. Respondents evaluated their organizations’ implementation of e-commerce supply chain practices using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). This instrument provided a reliable and valid foundation for measuring all constructs in the research model.

Furthermore, data were collected from a diverse group of respondents to minimize potential bias in subjectively rated elements. Participants represent different managerial levels, with 12.8% high-level managers, 49.0% middle-level managers, and 38.2% low-level managers.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the 539 respondents, including gender, managerial position, work experience, and company size.

Table 1 assess the representativeness of the sample by comparing its percentage distribution with the general population proportions of managerial employees in the relevant industry context. The demographic distribution of our sample, particularly in terms of managerial hierarchy and company size, aligns closely with the actual population structure, where middle-level managers and small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constitute the majority. This comparison supports the validity and representativeness of the sample used in this study.

5. Discussion

The study’s findings offer important insights into how AI-driven solutions can enhance the sustainability, resilience, and efficiency of e-commerce supply chains, whose operational characteristics differ markedly from those of traditional supply chains. E-commerce environments are defined by high order variability, short delivery windows, elevated return rates, fragmented last-mile logistics, and large-scale digital transactions. These frictions make the integration of AI not merely beneficial but essential. By interpreting the findings through the lens of these e-commerce specific challenges, the contribution of this study becomes more focused and compelling.

First, the significant impact of AI-driven demand forecasting on supply chain effectiveness becomes especially meaningful in the e-commerce context. Unlike traditional retail, e-commerce faces real-time fluctuations in customer orders, frequent promotional campaigns, and rapid shifts in consumer behavior across digital channels. The study confirms that AI technologies by processing high-velocity and high-variety datasets enable firms to anticipate these fluctuations with greater accuracy. This results in more responsive replenishment decisions, reduced safety stock buffers, and more synchronized last-mile fulfillment. Prior research also shows that digital intelligence increases informational processing capacity and reduces uncertainty in complex environments [

17], supporting our finding that accurate forecasting is foundational for managing e-commerce’s fast-paced, demand-driven system. The ability to avoid stockouts and oversupply is particularly critical in e-commerce, where delivery reliability directly affects conversion rates, customer retention, and platform competitiveness.

Second, the study highlights the crucial role of AI-enabled waste reduction in building sustainable e-commerce supply chains. Waste takes on unique forms in e-commerce, including excess packaging, inefficient routing in last-mile delivery, high rates of product returns, and unused warehouse energy due to fluctuating demand. AI’s ability to detect patterns such as return-prone products, inefficient delivery paths, or over-packaging tendencies helps mitigate sources of waste that are disproportionately large in digital commerce compared to traditional retail. This aligns with sustainability studies suggesting that digital intelligence improves organizational information-processing capabilities and reduces resource consumption [

34]. By optimizing packaging, consolidating delivery routes, and predicting return behaviors, firms can significantly lower their carbon footprint. Given increasing consumer pressure for eco-friendly e-commerce operations, AI-driven waste mitigation also strengthens brand reputation and customer trust [

6].

Third, the moderating role of supply chain efficiency between AI-driven forecasting and waste reduction is particularly relevant to e-commerce’s structural complexities. The study demonstrates that when AI improves supply chain efficiency through faster order processing, dynamic routing, and streamlined pick-and-pack operations, it directly reduces operational waste. This finding underscores the synergy between efficiency and sustainability in digital commerce, countering earlier assumptions that the two objectives might conflict [

66,

67]. In e-commerce ecosystems where small inefficiencies multiply due to high transaction volumes, achieving both goals simultaneously become not only feasible but necessary. AI facilitates this alignment by enhancing real-time information processing and coordination across warehousing, logistics, and customer interface systems.

Moreover, the study confirms that AI-driven sustainability practices significantly strengthen e-commerce supply chain resilience. E-commerce supply chains are particularly vulnerable to disruptions stemming from pandemics, supply bottlenecks, cyberattacks, last-mile disruptions, and sudden demand spikes. The findings show that AI-enhanced waste reduction and resource optimization increase a supply chain’s ability to absorb shocks and recover quickly, echoing broader research that positions resilience and sustainability as complementary outcomes enabled by digital technologies [

13,

74,

76,

78]. In e-commerce where speed, accuracy, and adaptability are competitive necessities, AI tools such as predictive analytics and anomaly detection are vital for reallocating resources, rerouting deliveries, and managing surge demand during disruptions.

Importantly, while this study focuses on e-commerce, the implications extend to other digitally intensive sectors such as smart manufacturing, retail logistics, and omnichannel distribution. Industries that experience similar challenges high demand variability, network fragmentation, and environmental pressure can adopt AI frameworks to improve operational visibility, sustainability performance, and resilience. Thus, the study offers a versatile perspective grounded in information-processing theory, showing how AI expands decision-making capacity under environmental uncertainty, much like the role of digital intelligence in green shipping operations.

Finally, the study contributes to the broader literature on AI in supply chain management by providing empirical evidence from the uniquely demanding e-commerce context. The findings confirm that AI-enhanced demand forecasting and waste reduction significantly improve sustainability, efficiency, and resilience, three performance dimensions central to e-commerce value delivery. Future research should further examine sector-specific dynamics such as return behavior patterns, customer-driven demand volatility, and last-mile logistics complexity. Additionally, scholars may explore the long-term risks of AI adoption including algorithmic bias, cyber vulnerabilities, and integration costs as well as cross-industry comparisons to deepen the theoretical understanding of AI’s role in digital-era supply chain management.

5.1. Practical Implications

The findings translate into immediate, operational actions that practitioners can implement to improve performance. Firms should deploy AI-driven demand forecasting calibrated with their own data and schedule regular retraining, while setting exception thresholds that trigger human review when forecast errors exceed defined limits. Waste-reduction analytics should be applied across materials, logistics, and energy flows, supported by dashboards that connect anomalies to specific process steps and suppliers for targeted interventions. Seamless integration with existing operations systems is essential: smaller firms can adopt modular, cloud-based tools that connect to current order, WMS, and POS systems to avoid heavy capital expenditure, whereas larger organizations should integrate AI services with ERP/TMS/WMS via APIs with strict version control and change management. Daily workflows need embedded governance through data validation pipelines, lineage tracking, audit logs, and explain ability reports for high-impact decisions, complemented by decision logs for compliance. Workforce enablement is critical, with role-specific training for planners, buyers, and logistics teams, alongside clearly defined human-in-the-loop escalation protocols for high-stakes decisions tied to sustainability targets. Progress should be monitored through a concise performance set, with forecast accuracy, inventory turns, stockouts, waste tonnage, energy intensity, and CO2e per order reviewed on a monthly cadence and linked to explicit targets.

5.2. Managerial Implications

From a leadership and governance perspective, managers should position AI as a strategic lever for resilience and sustainability rather than a narrow cost-cutting tool and formalize this stance through a governance charter that sets guardrails for model risk, privacy-by-design, and accountability. Building scalable capabilities requires investment in a central data/AI function that develops reusable assets such as feature stores, MLOPs, and data contracts, while establishing cross-functional stewardship among supply chain, IT, sustainability, and compliance. Organizational change must be supported by aligned incentives and KPIs so that planners and suppliers are rewarded for waste reduction and service-level gains, with clear escalation policies to prevent over-reliance on automation. Vendor and ecosystem choices should prioritize interoperability, explainability, and security, avoiding lock-in by favoring open standards and portable models and underpinned by supplier data-sharing agreements that balance transparency with confidentiality. Rigorous risk oversight is necessary through periodic audits for bias, drift, and segment-level performance, supported by comprehensive audit trails that satisfy regulatory and customer requirements for environmental claims. Finally, managers should adopt a staged roadmap from pilot to scale with explicit gates tied to ROI and sustainability impact and reinvest efficiency gains into circular economy initiatives and low-carbon logistics to compound long-term value.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

While the prior literature cautions that AI can introduce risks such as data privacy concerns, opacity in algorithmic decision processes, and organizational over-reliance, our results nonetheless show positive effects on supply chain resilience and sustainability. To reconcile these positions, we clarify why the observed risks did not undermine the measured benefits in our context and specify the conditions under which AI’s advantages are most likely to materialize.

First, the risks did not compromise the measured benefits because the study settings reflected practices that mitigate those risks. The participating firms operated with high-quality, well-governed datasets (e.g., consistent data schemas, robust data lineage, and periodic data audits), which reduced error propagation and limited bias in AI outputs. In addition, model transparency practices such as the use of interpretable model classes where feasible, post hoc explain ability tools, and decision logs enabled human supervisors to validate and contest AI recommendations, thereby curbing the downside of black-box decision-making. Finally, structured human-in-the-loop protocols and escalation rules prevented over-reliance on automated outputs in high-stakes decisions, maintaining managerial accountability and preserving domain expertise.

Second, our findings suggest several enabling conditions under which AI’s benefits to resilience and sustainability are likely to be realized: (1) data quality and integrity: standardized data pipelines, continuous data validation, and privacy-by-design safeguards that comply with relevant regulations; (2) algorithmic governance: model risk management routines, version control, performance monitoring across subpopulations, and clear accountability for model changes; (3) human oversight: defined review thresholds, exception handling, and periodic retraining aligned with operational changes; (4) organizational readiness: process integration, training for end users, and cross-functional stewardship that aligns AI objectives with the supply chain; (5) ethical and compliance frameworks: privacy impact assessments, access controls, and audit trails to ensure lawful and responsible AI use. Under these conditions, AI can enhance demand forecasting, waste reduction, and operational efficiency without amplifying the risks associated with opacity, privacy breaches, or automation bias.

In sum, the positive associations we observe are consistent with contexts where data governance, explain ability, and human oversight are embedded into AI deployment. By articulating why risks were contained in our setting and by delineating the boundary conditions for effective AI use, we provide a clearer theoretical account of when and why AI improves e-commerce supply chain resilience and sustainability and when insufficient governance may attenuate or reverse these gains.

6. Conclusions

The important role that AI-driven demand forecasting and waste reduction play in improving the sustainability and resilience of e-commerce supply chains has been examined in this study. The results highlight how AI has the potential to revolutionize supply chain management in the present era, when resilience, sustainability, and efficiency are not just desirable but also necessary for maintaining competitiveness in the global market. Businesses may optimize inventory levels, cut expenses, and avoid waste by using AI technology to estimate demand properly. This results in supply chains that are more sustainable and efficient. The study also emphasizes how AI-driven procedures help to increase supply chain resilience and save waste, which helps companies better endure interruptions and continue operations. Efficiency and sustainability have a synergistic relationship when AI is included into supply chain operations, with each supporting the other. This contradicts the conventional wisdom that these goals frequently clash and implies that businesses may accomplish both at the same time by strategically utilizing AI. Furthermore, the study’s conclusions apply not only to e-commerce but also to other sectors where sustainability and supply chain efficiency are important considerations. Businesses seeking to use AI for strategic advantage in a dynamic and unpredictable global environment might benefit greatly from the insights gathered.

6.1. Limitation

The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference and leaves open the possibility of reverse causality. The use of a single measurement waves and self-reported indicators introduces risks of common method variance and perceptual bias; although procedural and statistical checks were applied, residual common method bias may persist. The sampling frame and sectoral focus limit generalizability, and there is a lack of geographical representativeness, which constrains the applicability of findings across regions with different market, regulatory, and infrastructural conditions. Construct operationalization simplifies complex organizational practices and may introduce measurement error. Model specification choices leave potential residual confounding from omitted variables. Governance and transparency practices are inferred rather than directly audited, possibly overstating consistency of implementation. Finally, environmental outcomes are proxied by operational metrics rather than verified lifecycle assessments, limiting precision in estimating broader ecological impacts.

6.2. Further Research

AI adoption in supply chains raises several ethical concerns, such as issues related to data privacy, algorithmic biases, and the potential displacement of workers due to automation. It is crucial for future research to examine these ethical challenges and propose guidelines for implementing AI in a socially responsible manner. Additionally, businesses should be proactive in addressing potential privacy issues by ensuring that AI algorithms are transparent and accountable in their decision-making processes.

Future research should also explore the long-term effects of AI on workforce dynamics, particularly in the context of automation. While AI can enhance operational efficiency, its impact on labor markets such as job displacement or reskilling needs requires careful examination. Furthermore, longitudinal studies would help assess the sustainability outcomes of AI integration, including its effect on resource conservation, waste reduction, and overall environmental impact.

Future studies could also examine how AI can enhance supply chain traceability and transparency, offering consumers greater visibility into ethical sourcing and sustainability practices. Comparative studies across different industries or regions could provide additional insights into the broader applicability of AI in sustainable supply chains.