Advancing Climate Resilience Through Nature-Based Solutions in Southern Part of the Pannonian Plain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Natural Features of Vojvodina Province, Serbia

2.2. Data Sets for Other Spatial Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Climate Changes in Vojvodina

Rainfall Analysis: Extremes and Trends

- Wet years: Specifically, 1999 (927.0 mm), 2010 (911.6 mm), and 2014 (879.6 mm) exhibited high annual precipitation, with corresponding SPI values reflecting “Wet” and “Extremely Wet” conditions. In 2010, extreme precipitation was recorded, with SPI indicating three months in the “Wet” category and two months as “Extremely Wet”, aligning with the high rainfall total of 911.6 mm (Figure 2a).

- Normal years: Years with near-average precipitation, such as 1981 (771.6 mm), 1991 (717.3 mm), and 1976 (a little above 600 mm), predominantly showed SPI values within the “Normal” range (−1 < SPI < 1), indicating relatively stable hydrometeorological conditions. In 1991, for example, most months were classified as “Normal”, with only occasional deviations toward wetter or drier categories (Figure 2b).

- Dry years: Conversely, drier years such as 2000, which recorded only 295.3 mm of annual precipitation, showed a significant number of months in the “Drought” category (−2 < SPI ≤ −1). Specifically, in 2000, five months were classified as “Drought”, which is consistent with the extremely low precipitation recorded that year, and can be interpreted as a period of extreme dryness (Figure 2c).

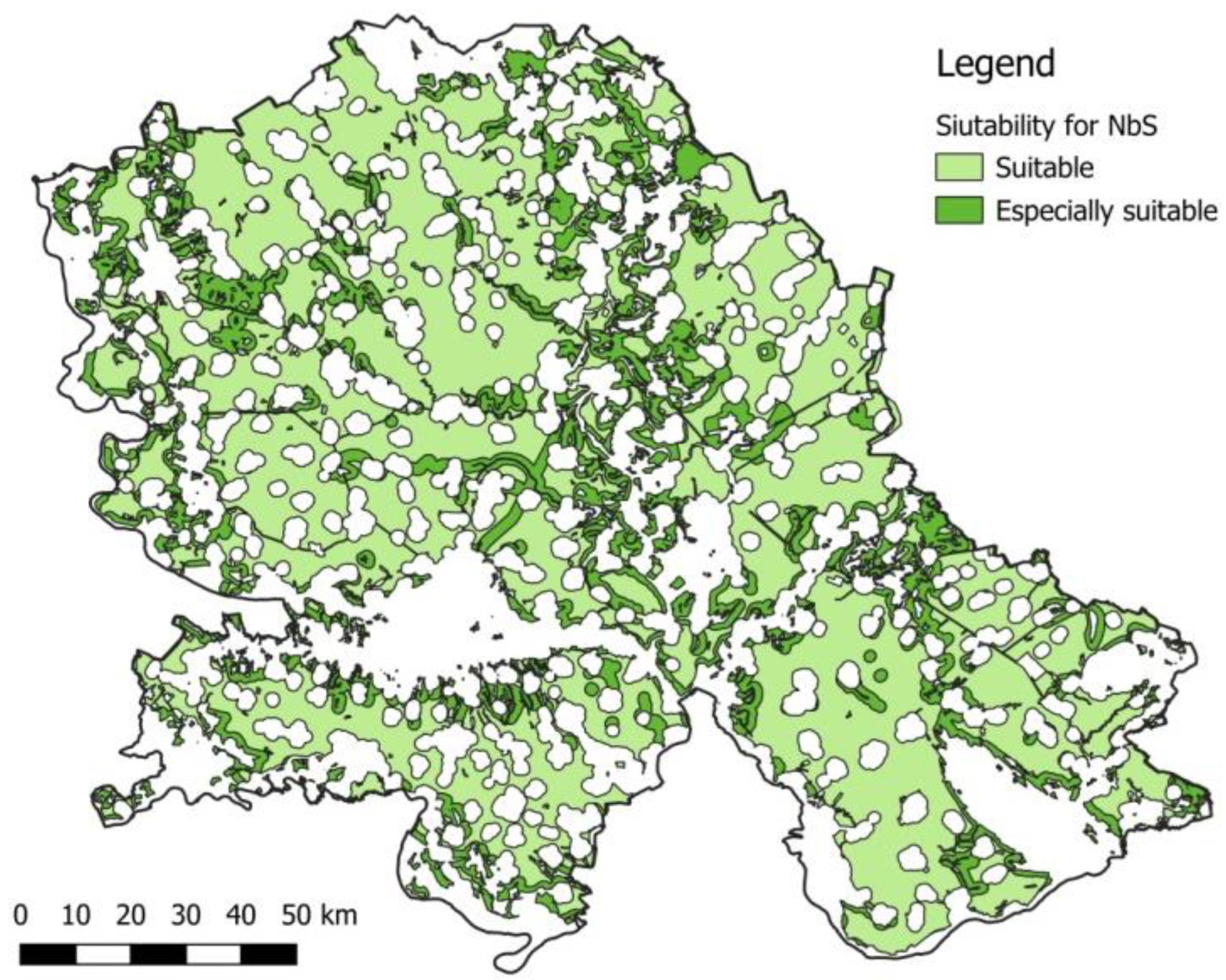

3.2. Natural Potentials Within the Vojvodina’s Landscape

Forests and Non-Forest Greenery

4. The Connection of NbS and Best Practice Implementation

4.1. A Nature-Based Solution That Incorporates Sustainable Agriculture

4.2. NbS in Sustainable Agriculture of Vojvodina

- The differences between sustainable agriculture and NbS concepts are how they address the problem. While NbS has a top-down approach, sustainable agriculture mostly uses a bottom-up approach.

- NbS relies on and develops carbon farming and carbon offsetting schemes in partnership with major conservation groups, while sustainable agriculture aims at building soil carbon in the long term.

- Sustainable agriculture systems use a food system approach (from field to fork) while NbS addresses sustainable land and water resources management, which support food systems development.

- NbS is more focused on global benefits, while sustainable agriculture emphasizes improvements on the local level.

- NbS and sustainable agriculture share similar principles and have the same human well-being outcomes.

- NbS is adherent to the territorial level—integrated into the specific area, which is why the joint action and synergism of NbS and sustainable agriculture can lead to multiple benefits in agriculture.

- With both concepts, farmers and other food producers are positioned to be some of the most important stewards of the world’s lands and water resources.

- Both are inclusive, addressing societal challenges, and convenient for scaling up.

- Together (NbS and sustainable agriculture) they can improve agricultural production by resolving difficulties in encompassing the farm vs. food systems scale.

4.3. Ecological Network

4.4. Grazing Within Protected Areas

5. A Roadmap for the Implementation of NbS in Vojvodina Province

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.H.; Salam, J. Resilience, Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies to Combat Climate Change for a Sustainable Future. Int. J. Environ. Clim. 2025, 15, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, M.D.; Duffield, S.; Harley, M.; Pearce-Higgins, J.W.; Stevens, N.; Watts, O.; Whitaker, J. Measuring the success of climate change adaptation and mitigation in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 2019, 366, eaaw9256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.; Bledsoe, B.; Ferreira, S.; Nibbelink, N. Challenges to realizing the potential of nature-based solutions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolz, K.J.; De Lucia, E.H. Alley cropping: Global patterns of species composition and function. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 252, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 97, p. 2036. [Google Scholar]

- Bauduceau, N.; Berry, P.; Cecchi, C.; Elmqvist, T.; Fernandez, M.; Hartig, T.; Krull, W.; Mayerhofer, E.N.S.; Noring, L.; Raskin-Delisle, K.; et al. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities: Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ‘Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’; Publications Office of the European Union: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015; 76p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, B.G.; Merbis, J.S.; Alfarra, M.D.A.; Ünver, O.; Arnal, M.A. Nature-Based Solutions for Agricultural Water Management and Food Security. FAO Land and Water Discussion Paper No. 12; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; 66p, Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/CA2525EN/ca2525en.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Nature-Based Solutions in Agriculture—Sustainable Management and Conservation of Land, Water and Biodiversity; FAO and The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Jacobs, S. Nature-Based Solutions for Europe’s Sustainable Development. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization—WHO. Communicating on Climate Change and Health: Toolkit for Health Professionals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376283 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Castellari, S.; Zandersen, M.; Davis, M.; Veerkamp, C.; Förster, J.; Marttunen, M.; Mysiak, J.; Vandewalle, M.; Medri, S.; Picatoste, J.R. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation; Disaster Risk Reduction. EEA Report No 1/2021, Issue. 2021. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/da65d478-a24d-11eb-b85c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, S.; Vale, M.M.; Malecha, A.; Pires, A.P.F. Nature-based solutions promote climate change adaptation safeguarding ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 55, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabic, J. Wetlands in Serbia: Past, present and future. Columella 2024, 11, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agri-Environmental Indicator—Soil Erosion. Data Extracted in February 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agri-environmental_indicator_-_soil_erosion (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Srejić, T.; Manojlović, S.; Sibinović, M.; Bajat, B.; Novković, I.; Milošević, M.V.; Carević, I.; Todosijević, M.; Sedlak, M.G. Agricultural Land Use Changes as a Driving Force of Soil Erosion in the Velika Morava River Basin, Serbia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia—2024. Municipalities and Regions of the Republic of Serbia, Republic Statistical Office of the RS. Belgrade. Posted on 25 December 2024. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/sr-latn/publikacije/publication/?p=17065&tip=13 (accessed on 20 January 2025). (In Serbian)

- Public Water Management Company Vojvodina Vode—PWMC VV. Hidrosystem Dunav-Tisa-Dunav—HS DTD. Available online: https://vodevojvodine.com/en/water-resources/dtd-hs/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Dragović, S.; Maksimović, L.; Radojević, V.; Cicmil, M.; Pantelić, S. Historical development of soil water regime management using drainage and irrigation in Vojvodina. Vodoprivreda 2005, 37, 216–218+285–296. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Vranešević, M.; Salvai, A.; Bezdan, A.; Zemunac, R. Assessment of Runoff and Drainage Conditions in a North Banat Sub-Catchment, North-Eastern Serbia. J. Environ. Geogr. 2019, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Nature Conservation of Vojvodina Province—INCVP. Register of Protected Areas. Available online: https://pzzp.rs/zastita-prirode/zastita-prirode/registar-zasticenih-podrucja.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Belic, S.; Rajkovic, M. Conditions that land reclamation must ensure sustainable agriculture. Stud. Univ. Vasile Goldiş Arad Ser. Vietii 2010, 20, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia for 2022. Republic Statistical Office of the RS. Belgrade. Posted on 20 October 2022. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/sr-Latn/publikacije/?d=2&r=2 (accessed on 20 June 2025). (In Serbian)

- Lalic, B.; Mihailovic, D.; Podraščanin, Z. Future state of climate in Vojvodina and expected effects on crop production. Field Veg. Crop Res. 2011, 48, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošić, I.; Hrnjak, I.; Gavrilov, M.; Unkašević, M.; Marković, S.; Lukić, T. Annual and seasonal variability of precipitation in Vojvodina, Serbia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014, 117, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarin, B.; Lukić, T.; Mesaroš, M.; Pavić, D.; Đorđević, J.; Matzarakis, A. Spatial and temporal analysis of extreme bioclimate conditions in Vojvodina, Northern Serbia. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia—RHMSS. Metheorological Yearbooks, Climataological Data; Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 1971–2019. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration of time scales. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, American Meteorological Society, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–23 January 1993; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Corine Land Cover—CLC, Version 20; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018.

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Planet Dump [Data File from $Date of Database Dump$]. Available online: https://planet.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- EEA—European Environmental Agency, Datahub. EUNIS Habitat Distribution Plots (Spatial Data). Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/ce3e4bf4-e929-404a-88c7-37f2c614fd1d (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Chi, W.; Wang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Na, Y.; Luo, Q. Effect of Land Use/Cover Change on Soil Wind Erosion in the Yellow River Basin since the 1990s. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Jiao, J.; Jian, J.; Bai, L.; Li, J.; Ma, X. Impact of Land Use/Cover Changes on Soil Erosion by Wind and Water from 2000 to 2018 in the Qaidam Basin. Land 2023, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudić, B.; Orlović, S.; Galović, V.; Pekeč, S.; Stojanović, D.; Stojnić, S. Molecular Technologies in Serbian Lowland Forestry under Climate Changes—Possibilities and Perspectives. South East Eur. For. 2014, 5, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niketić, M.; Tomović, G.; Bokić, B.; Buzurović, U.; Duraki, Š.; Đorđević, V.; Sanjaf, Đ.; Zorang, K.; Predragb, L.; Ranko, P.; et al. Material on the annotated checklist of vascular flora of Serbia: Nomenclatural, taxonomic and floristic notes III. Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. Belgr. 2021, 14, 77–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šurbanovski, N.; Tobutt, K.; Konstantinović, M.; Maksimović, V.; Sargent, D.; Stevanović, V.; Ortega, E.; Bošković, R. Self-incompatibility of Prunus tenella and evidence that reproductively isolated species of Prunus have different SFB alleles coupled with an identical S-RNase allele. Plant J. 2007, 50, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Milojković, D.; Ristić, V.; Nechita, F.; Maksin, M.; Štetić, S.; Candrea, A.N. Sustainable Tourism of Important Plant Areas (IPAs)—A Case of Three Protected Areas of Vojvodina Province. Land 2023, 12, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseldžija, M.; Dudić, M.; Stipanović, S. Distribution of the invasive species Ailanthus altissima (P. Mill.) Swingle along the Danube river banks on the territory of Novi Sad. Contemp. Agric. 2019, 68, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabić, J.; Ljevnaić-Mašić, B.; Zhan, A.; Benka, P.; Heilmeier, H. A review on invasive false indigo bush (Amorpha fruticosa L.): Nuisance plant with multiple benefits. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabić, J.; Benka, P.; Ljevnaić-Mašić, B.; Vasić, I.; Bezdan, A. Spatial distribution assessment of invasive alien species Amorpha fruticosa L. by UAV-based on remote sensing in the Special Nature Reserve Obedska Bara, Serbia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetaković, J.; Čortan, D.; Maksimović, Z. Conservation of European White Elm; Black Poplar Forest Genetic Resource: Case Study in Serbia. In Forests of Southeast Europe Under a Changing Climate; Šijačić-Nikolić, M., Milovanović, J., Nonić, M., Eds.; Advances in Global Change Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, P.; Romelić, J.; Kicošev, S.; Lazić, L. Vojvodina, Scientifically Popular Monograph; Geographic Society of Vojvodina: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Štetić, S.; Ristić, V.; Trišić, I.; Tomašević, V.; Skenderović, I.; Kurpejović, J. Nature Conservation and Tourism Sustainability: Tikvara Nature Park, a Part of the Backo Podunavlje Biosphere Reserve Case Study. Forests 2025, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, L.; Pavić, D.; Stojanović, V.; Tomić, P.; Romelić, J.; Pivac, T.; Košić, K.; Besermenji, S.; Kicošev, S. Protected Natural Resources and Ecotourism in Vojvodina; Departman za Geografiju, Turizam i Hotelijerstvo, Prirodno-Matematički Fakultet, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2008. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Obradov, D.P.; Radak, B.Đ.; Bokić, B.S.; Anačkov, G.T. Floristic diversity of the central part of the South Bačka loess terrace (Vojvodina, Serbia). Biol. Serbica 2021, 42, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tmušić, G.M.; Rat, M.M.; Bokić, B.S.; Radak, B.Đ.; Radanović, M.M.; Anačkov, G.T. Floristic analysis of the Danube’s shoreline from Čerević to Čortanovci. Matica Srp. J. Nat. Sci. 2019, 136, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćuk, M. Status and Temporal Dynamics of Flora; Vegetation of Deliblatsko Sands. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Biology, Faulty of Sciences, Ecology, University of Novom Sadu, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2019. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, I.H.; Morello, E.; Vona, C.; Benciolini, M.; Sejdullahu, I.; Trentin, M.; Pascual, K.H. Setting the social monitoring framework for nature-based solutions impact: Methodological approach and pre-greening measurements in the case study from CLEVER cities Milan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, D.; Rice, C. Soil Degradation: Will Humankind Ever Learn? Sustainability 2015, 7, 12490–12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat Skenderović, T. Vita Organica; Terras; Printex: Subotica, Serbia, 2023; pp. 1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaš Simin, M.; Milić, D.; Novaković, D.; Zekić, V.; Novaković, T. Organic Agriculture in Focus: Exploring Serbian Producers’ Views on the Common Agricultural Policy and the National Agrarian Policy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeremešić, S.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Tomaš Simin, M.; Milašinović Šeremešić, M.; Vojnov, B.; Brankov, T.; Rajković, M. Articulating Organic Agriculture and Sustainable Development Goals: Serbia Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management—MAFWM (2025 March). Organic Agriculture. Available online: http://www.minpolj.gov.rs/organska/?script=lat (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Budding-Polo Ballinas, M.; Arumugam, P.; Verstand, D.; Siegmund-Schultze, M.G.R.; Keesstra, S.D.; Garcia Chavez, L.Y.; de Boer, R.; van Eldik, Z.C.S.; Voskamp, I.M. Discussion Paper: Nature Based Solutions in Food Systems: Review of Nature-Based Solutions Towards More Sustainable Agriculture and Food Production. Wageningen University & Research, 2022. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/578174 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Đorić, Ž. Zelena Ekonomija I Održivi Razvoj U Zemljama Zapadnog Balkana (Green Economy; Sustainable Development In The Western Balkan Countries). Ekon. Ideje I Praksa 2021, 41, 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Popovicki, T. Study on Nature-Based Climate Solutions in Serbia. United Nations Development Programme. 2019, pp. 1–48. Available online: https://www.undp.org/serbia/publications/study-nature-based-climate-solutions-serbia (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cooper, T.; Pezold, T.; Keenleyside, C.; Đorđević-Milošević, S.; Hart, K.; Ivanov, S.; Redman, M.; Vidojević, D. Developing a National AgriEnvironment Programme for Serbia; IUCN Programme Office for South-Eastern Europe: Gland, Switzerland; Belgrade, Serbia, 2010; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Šeremešić, S.; Milošev, D.; Nikolić, L.; Lazić, B.; Jug, D.; Đurđević, B. High nature value farming concept in agriculture and environment. In Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific/Professional Conference, Agriculture in Nature and Environment Protection, Vukovar, Croatia, 27–29 May 2013; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Khangura, R.; Ferris, D.; Wagg, C.; Bowyer, J. Regenerative Agriculture—A Literature Review on the Practices; Mechanisms Used to Improve Soil Health. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelton, E.; Carew-Reid, J.; Coulier, M.; Damen, B.; Howell, J.; Pottinger-Glass, C.; Tran, H.V.; van Der Meiren, M. NBS framework for agricultural landscapes. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 678367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law on Nature Protection, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, Nos. 36/09 of 15 May 2009, 88/10 of 23 November 2010, 91/10 of 3 December 2010 (Corrigendum), 14/16 of 22 February 2016 and 95/18 of 8 December 2018 (Other Law). Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_zastiti_prirode.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Kicošev, V.; Mesaroš, M.; Veselinović, D.; Sabadoš, K. Uspostavljanje zona unutar zaštitnih pojaseva prirodnih dobara u funkciji prilagođavanja na klimatske promene (Establishing a zone within the protection belts of natural assets for the purpose of climate change adaptation). Ecologica 2013, 20, 181–187. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- European Commision, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Green Infrastructure (GI): Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital (COM(2013) 249 Final of 6 May 2013). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52013DC0249 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Stec, A.; Słyś, D. New bioretention drainage channel as one of the low-impact development solutions: A case study from Poland. Resources 2023, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicošev, V.; Vasin, J.; Kvaščev, M.; Bibin, M.; Bošnjak, I.; Đukić, D.; Senji, L. The issue of determining the amount of deposited nitrogen compounds in salt-affected habitats within the national ecological network. Ratar. I Povrt./Field Veg. Crops Res. 2014, 51, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation on the Protection of the Special Nature Reserve Selevenjske Pustare, RS Official Gazette, No.37/97. Available online: http://demo.paragraf.rs/demo/combined/Old/t/t2008_07/t07_0065.htm (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Steklová, J.; Novák, J.; Češká, J. Managed and unmanaged permanent grasslands: Species composition at selected localities of the protected landscape area Šumava (Bohemian forest; The Czech Republic) depending on the soil. Cereal Res. Commun. 2008, 36, 831–834. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, E.E.; Webber, H.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Durand, J.L.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; MacCarthy, D.S. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, V.; Drešković, N.; Mihailovic, D.; Mimić, G.; Arsenic, I.; Đurđević, V. Which is the response of soils in the Vojvodina Region (Serbia) to climate change using regional climate simulations under the SRES-A1B? Catena 2017, 158, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabić, J.; Đurić, S.; Ćirić, V.; Benka, P. Water quality at special nature reserves in Vojvodina, Serbia. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 10, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranešević, M.; Belić, S.; Kolaković, S.; Kadović, R.; Bezdan, A. Estimating suitability of localities for biotechnical measures on drainage system application in Vojvodina. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 66, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Živanović Miljković, J.; Crnčević, T. Multifunctional Urban Agriculture; Agroforestry for Sustainable Land Use Planning in the Context of Climate Change in Serbia. In Climate Change-Resilient Agriculture; Agroforestry; Castro, P., Azul, A., Leal Filho, W., Azeiteiro, U., Eds.; Climate Change Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnov, B.; Jaćimović, G.; Šeremešić, S.; Pezo, L.; Lončar, B.; Krstić, Đ.; Vujić, S.; Ćupina, B. The Effects of Winter Cover Crops on Maize Yield and Crop Performance in Semiarid Conditions—Artificial Neural Network Approach. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warlo, H.; Kautz, M. How do global forest pests respond to increasing temperatures?–A meta-analysis. Oikos 2024, 11, e10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, L.J.; Stockan, J.; Helliwell, R. Managing riparian buffer strips to optimise ecosystem services: A review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 296, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benka, P.; Grabić, J.; Ilić, M.; Srđević, B.; Srđević, Z. Koviljsko-petrovaradinski rit Special Nature Reserve (KPR), Serbia: [Chapter 3.2.4]. In Ecosystem Services in Floodplains and Their Potential to Improve Water Quality; Julia, S., Andreas, G., Adrian, L., Barbara, S., Eds.; Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt [u.a.]: Eichstadt, Germany, 2022; pp. 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, T.R., Jr.; Rasera, K.; Parron, L.M.; Brito, A.G.; Ferreira, M.T. Nutrient removal effectiveness by riparian buffer zones in rural temperate watersheds: The impact of no-till crops practices. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Rohrbach, D.; Nowak, A.; Girvetz, E. An Introduction to the Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers. In An Introduction to the Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers: Investigating the Business of a Productive, Resilient and Low Emission Future; Rosenstock, T.S., Nowak, A., Girvetz, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campese, J.; Mansourian, S.; Walters, G.; Nuesiri, E.O.; Hamzah, A.; Brown, B.; Kuzee, M.; Nakangu, B. Enhancing the Integration of Governance in Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities Assessments; IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy (CEESP), IUCN, Human Rights in Conservation; IUCN—International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/x1ghkf (accessed on 16 October 2024). COI: 20.500.12592/x1ghk.

- Ilić, M.; Srđević, Z.; Srđević, B.; Stammel, B.; Borgs, T.; Benka, P.; Grabić, J.; Ždero, S. The nexus between pressures and ecosystem services in floodplains: New methods to integrate stakeholders’ knowledge for water quality management in Serbia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 68, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seremesic, S.; Grabic, J.; Ninkov, J.; Altobelli, F.; Milasinovic-Seremesic, M.; Vojnov, B. Nature Based Solution framework for Agro-ecological transition in Serbia. In Book of Abstract Centennial Celebration and Congress of the International Union of Soil Sciences Florence—Italy; 19–21 May 2024; ID ABS, WEB 137875; International Union of Soil Sciences: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1mcbITzR1wfY1b4vLAaceHAyg_y_K3vzq/view (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Biró, M.; Molnár, Z.; Babai, D.; Dénes, A.; Fehér, A.; Barta, S.; Sáfián, L.; Szabados, K.; Kiš, A.; Demeter, L.; et al. Reviewing historical traditional knowledge for innovative conservation management: A re-evaluation of wetland grazing. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biró, M.; Molnár, Z.; Öllerer, K.; Lengyel, A.; Ulicsni, V.; Szabados, K.; Kiš, A.; Perić, R.; Demeter, L.; Babai, D. Conservation and herding co-benefit from traditional extensive wetland grazing. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 300, 106983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, L.; Kiš, A.; Kemenes, A.; Ulicsni, V.; Juhász, E.; Đapić, M.; Bede-Fazekas, Á.; Szabados, K.; Öllerer, K.; Molnár, Z. Uncovering the little known impact of a millennia-old traditional use of temperate oak forests: Free-ranging domestic pigs markedly change the herb layer, but barely affect the shrub layer. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 568, 122150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josimov-Dunderski, J.; Belic, A.; Salvai, A.; Grabic, J. Age of constructed wetland and effects of wastewater treatment. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Josimov-Dundjerski, J.; Savić, R.; Belić, A.; Salvai, A.; Grabić, J. Sustainability of the Constructed Wetland Based on the Characteristics in Effluent. Soil Water Res. 2015, 10, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Backo Podunavlje, Serbia. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/backo-podunavlje (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- UNESCO. Mura-Drava-Danube Biosphere Reserve. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/mura-drava-danube-0 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Hermoso, V.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Lanzas, M.; Brotons, L. Designing a network of green infrastructure for the EU. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SPI Value | Drought Conditions | SPI Value | Wet Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| −2.0 and below | extreme drought | 2.0 and above | extremely wet |

| −2.0 to −1.5 | severe drought | 1.5 to 2.0 | very wet |

| −1.5 to −1.0 | moderate drought | 1.0 to 1.5 | moderately wet |

| −1.0 to 0.0 | near normal (mild drought) | 0.0 to 1.0 | near normal (mild wet) |

| Latin Name | English Name | References |

|---|---|---|

| Forests, native species | ||

| Populus nigra L. | Black poplar | [43] |

| Salix alba L. | White willow | [44] |

| Quercus robur L. | English oak | [45] |

| Fraxinus excelsior L. | European ash | [46] |

| Acer campestre L. | Field maple | [39] |

| Meadows and pastures, open grasslands | ||

| Festuca pratensis Tourn ex L. | Meadow fescue | [47] |

| Lolium perenne L. | Perennial ryegrass | [48] |

| Trifolium pratense L. | Red clover | [48] |

| Medicago sativa L. | Alfalfa | [48] |

| Shrublands | ||

| Prunus spinosa L. | Blackthorn | [49] |

| Rosa canina L. | Dog rose | [49] |

| Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Common hawthorn | [46] |

| Prunus tenella Batsch, 1801 | Dwarf Russian almond | [49] |

| Cornus sanguinea L. | Common dogwood | [49] |

| Wetlands | ||

| Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | Common reed | [46] |

| Typha latifolia L. | Broadleaf cattail | [49] |

| Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. | Black alder | [46] |

| Carex elata All. | Tufted sedge | [46] |

| Nymphaea alba L. | White water lily | [45] |

| Protective greenery | ||

| Robinia pseudoacacia L. | Black locust | [39] |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | Swingle, Tree of heaven | [40] |

| Platanus × acerifolia (Aiton) Willd. | London plane | [47] |

| Tilia cordata Mill. | Small-leaved lime | [49] |

| Ulmus minor Mill. | Field elm | [46] |

| Category | Area (ha) | Area % |

|---|---|---|

| High greenery | 143,057 | 6.61 |

| Low greenery | 284,418 | 13.15 |

| Without greenery | 1,735,820 | 80.24 |

| Distance-Based Classes to the Nearest Non-Forest Greenery (km) | Number of Identified Patches | Overall Size of Patches That Are at the Same Distance from Other Patches (ha) | Shares Under Non-Forest Greenery According to the Distance-Based Classes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1894 | 418,031.58 | 97.79 |

| 1 | 103 | 6723.78 | 1.57 |

| 2 | 28 | 1835.07 | 0.43 |

| 3 | 11 | 431.00 | 0.10 |

| 4 | 4 | 199.85 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 1 | 30.93 | 0.01 |

| 6 | 1 | 66.01 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 1 | 157.36 | 0.04 |

| Distance-Based Classes (km) from the Nearest Non-Forest Greenery | The Sum of Patch Areas Under the Same Distance Category (ha) | The Sum of Patch Areas Under the Same Distance-Based Class % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 868,879 | 50.06 |

| 2 | 434,519 | 25.03 |

| 3 | 241,483 | 13.91 |

| 4 | 121,601 | 7.01 |

| 5 | 51,560 | 2.97 |

| 6 | 14,875 | 0.86 |

| 7 | 2478 | 0.14 |

| 8 | 423 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grabić, J.; Vranešević, M.; Benka, P.; Šeremšić, S.; Meseldžija, M. Advancing Climate Resilience Through Nature-Based Solutions in Southern Part of the Pannonian Plain. Sustainability 2026, 18, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010362

Grabić J, Vranešević M, Benka P, Šeremšić S, Meseldžija M. Advancing Climate Resilience Through Nature-Based Solutions in Southern Part of the Pannonian Plain. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010362

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrabić, Jasna, Milica Vranešević, Pavel Benka, Srđan Šeremšić, and Maja Meseldžija. 2026. "Advancing Climate Resilience Through Nature-Based Solutions in Southern Part of the Pannonian Plain" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010362

APA StyleGrabić, J., Vranešević, M., Benka, P., Šeremšić, S., & Meseldžija, M. (2026). Advancing Climate Resilience Through Nature-Based Solutions in Southern Part of the Pannonian Plain. Sustainability, 18(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010362