1. Introduction

The concept of bioregions is a relatively new, innovative approach to the development of rural areas, which includes economic, social, environmental and ethical aspects [

1,

2,

3,

4]. At the political level, a biological region (bioregion) is defined as follows: a ‘bio district’ is a geographical area where farmers, the public, tourist operators, associations and public authorities enter into an agreement for the sustainable management of local resources, based on organic principles and practices. The aim is to maximise the economic and sociocultural potential of the territory. Each ‘bio district’ includes lifestyle, nutrition, human relations and nature considerations [

5]. Under this system, organic farming as a practice and the farmers who practice it play a key role [

4,

6]. The bioregion concept is described in the literature using various terms, such as “bioregion”, “bio-district”, “eco-district” and “eco-region”, although in some disciplines, the latter terms refer to ecological or biogeographical classifications rather than territorial development concepts [

3,

4,

7,

8,

9]. To quantitatively substantiate the topicality of the bioregion concept, the dynamics of scientific publications indexed in the Scopus database were analysed using the keywords “bioregion”, “bio-district(s)” and “ecoregion”. For the keyword “bioregion”, a total of 302 publications were identified, of which 135 were published in 2010–2014, 75 in 2015–2019, and 131 in 2020–2024, indicating a renewed growth trend in the most recent period. The use of the keyword “bio-district(s)” in the academic literature is relatively recent but rapidly increasing: no publications were identified before 2014, whereas 12 publications were recorded in 2020–2024. In contrast, the keyword “ecoregion” shows a broad and long-established scientific base, with a total of 3230 publications and a consistent increase across all analysed periods. At the same time, following the approach of Giacomo Packer (2025) [

10], a share of these publications was excluded from the in-depth analysis, as they focus on ecological regions or biodiversity conservation rather than on bioregions or bio-districts as concepts of territorial development and governance. Overall, these results are consistent with the conclusions of Packer’s (2025) [

10] systematic literature review, which also highlights a growing number of publications; however, the existing research remains limited in scope and is mainly focused on individual case studies and their comparisons [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The experience of the first bioregion (Cilento Bio-district in Italy) has been analysed by several authors [

12,

15]. Some of the research studies are devoted to the classification and identification of bioregions [

12,

16]. The concept of bioregions has also been researched as a tool for implementing the circular economy [

17]. The concept of agroecology, which has gained attention in Italy, has been studied in comparison with the concept of bioregions, thus finding similarities between the two approaches [

18,

19]. In fact, there has been an increase in the basis of academic literature in recent years, which, in the opinion of the authors, indicates the topicality of the concept of bioregions. This trend is further complemented by the authors’ recent studies on the economic impact of local food systems, which provide additional context for understanding the potential of the bioregion approach in regional development [

20,

21].

Although the concept of bioregions is increasingly being analysed in the academic literature and several approaches to its interpretation, categories and applications have been identified, there is still a lack of tools in the scientific discourse that would allow us to quantitatively compare different development scenarios for bioregions and to determine which factors are most relevant in specific areas. The development of bioregions is a multidimensional process affected by economic, social, cultural and environmental aspects, and the interdependence of the factors varies considerably across regions. Consequently, a methodology is needed that allows us to set priorities in a structured and reasoned way, align qualitative and quantitative information and base decisions on expert ratings. This methodological gap is especially indicated by the approaches identified by the literature review; for example, classifications of bioregions and case studies provide valuable insight into the development of the concept, yet they do not provide a tool that would allow us to systematically assess the potential development opportunities for bioregions in new, not yet established areas, as is necessary in the case of Latvia.

In studies on sustainable development and regional planning, multivariate evaluation methods are widely applied to analyse complex systems in which economic, social, and environmental factors interact simultaneously. In quantitative data analysis, principal component analysis (PCA) is frequently employed to reduce the number of variables and to identify dominant patterns of variation in multidimensional datasets [

22,

23]. PCA is based on statistical relationships among variables and is suitable for describing and comparing data structures. However, PCA provides limited support for the prioritisation of alternative development scenarios, as it does not allow for the weighting of criteria according to preference systems and does not explicitly integrate expert judgements [

24]. Therefore, in studies where structured decision-making and the integration of multiple sustainability dimensions are required, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods are more commonly applied, including the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [

25,

26]. This approach fully corresponds to the aim of the present study, which involves the comparison of alternative bioregional development scenarios based on expert evaluations.

In the study of Assiri et al. (2021) [

27], the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) was applied as a multi-criteria decision-making method to structure and evaluate a set of biological, agricultural, environmental, social and economic criteria relevant to the identification of areas suitable for the application of a bioregional approach. The inclusion of biological and agricultural characteristics, together with environmental, social and economic dimensions, reflects the multidimensional nature of bioregional development and its dependence on territorial sustainability factors. Based on this AHP-based evaluation framework, Assiri et al. (2021) subsequently developed the Ecoregional Vocation Index (EVI) as an aggregated measure to assess the suitability of territories for the establishment of bioregions. The EVI serves as an example of how structured multi-criteria assessment methods can be operationalised into composite indicators for spatial planning purposes. As highlighted by Assiri et al. (2021) [

27], the identification of suitable areas for bioregional development requires the application of structured multi-criteria evaluation methods capable of integrating diverse territorial factors—a methodological challenge that is also addressed in the present research.

Strategies for the development of areas, including bioregions, are essential to identify real factors that can create a relative advantage for bioregions. Using site-specific indicators, it is possible to cluster areas through identifying potential bioregional development pathways that focus on tourism, organic farming, education and nature protection, as well as identify those without pronounced prerequisites for the creation of bioregions and areas where intensive production generates too many benefits that limit the development of bioregions [

28]. At the same time, the use of such an analytical approach depends on expert evaluation.

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [

26,

29] is relatively widely used in territorial development and policymaking, representing an effective approach to complex decision-making related to the prioritisation of various aspects of development and the allocation of resources [

30,

31,

32]. In a research study on territorial development priorities for the municipality of Zawidz (Poland) [

33], AHP was used for spatial planning, including decision-making, with the method providing a structured and systematic approach to decision-making based on ratings by industry experts. The research study showed how AHP helps to identify priority pathways for land use by employing proper indicators and methodology, thereby leading to a comprehensive assessment of factors. The case of Zawidz municipality demonstrates that AHP can be applied in practice to select the most optimal uses for land in the municipal territory, thus improving the efficiency and transparency of decision-making. Similarly, AHP has been used in Poland to prioritise land consolidation in rural areas with severe fragmentation of agricultural land [

34]. The research study was conducted in the municipality of Sławno, where land fragmentation significantly limited the development of agricultural production. Using AHP, the research study identified rural areas and village territories where consolidation could make the largest contribution, thus increasing land use efficiency and access to modern agricultural technologies. However, Palka et al. (2020) [

35] have focused on the effectiveness of strategic territorial planning in Lyon, France, and Copenhagen, Denmark, using AHP.

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method has also been widely applied in Latvia for the evaluation of regional and territorial development scenarios, investment decisions, and land use alternatives. One of the most significant publications demonstrating the application of AHP in Latvia is the study by Rivža and Rivža (2009) [

36], which analysed the use of AHP in territorial planning and the evaluation of regional development projects, for example, by identifying the most suitable locations for the construction of grain processing facilities or for defining sugar production strategies. The study employed the principle of pairwise comparisons to prioritise alternative development scenarios, which is essential for the formulation of effective and sustainable regional development strategies. Continuing this line of research, Auziņš (2016) [

37], in a study on land use assessment and management, developed a multi-level indicator system to evaluate land use efficiency, applying the AHP method to determine the relative weights of criteria based on expert judgement, while taking into account planning needs at both the national and municipal levels. This approach enabled a detailed assessment of land use efficiency and supported well-founded decision-making regarding future development. A similar methodological approach was applied by Jeroscenkova et al. (2016) [

38] in a study on the conservation of cultural heritage and its use in rural tourism as an integral component of Latvia’s sustainable development policy. Based on expert evaluations, the study assessed the most appropriate scenarios for the use of cultural heritage in rural tourism development and compared alternative development strategies, thereby promoting informed decision-making in line with regional conditions. The AHP method was also used in the development of long-term development plans for the Latgale region [

39], where experts evaluated strategic scenarios, priorities, and sustainability indicators within the context of the region’s development potential. In addition to the studies mentioned above, the application of AHP in Latvia has been documented in analyses of smart specialisation development in the Vidzeme region [

40], evaluations of the potential use of degraded areas [

41], and studies on sustainable and smart entrepreneurship development at the municipal level [

42]. Overall, these studies demonstrate that the AHP method has been successfully applied across various planning domains in Latvia, fostering an integrated approach and supporting well-founded decision-making for the promotion of sustainable development.

The reviewed studies indicate that the application of AHP in territorial research is characterised by a flexible approach to the design of criteria and subcriteria, which is directly related to the specific objective of each study [

26,

27]. In some studies, AHP is applied to construct composite territorial indices based on detailed biophysical and territorial indicators [

27], whereas in other cases, AHP primarily serves as a decision-support tool for the comparison and prioritisation of alternative development scenarios based on expert evaluations [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Consequently, the system of criteria and subcriteria applied in the present study is methodologically sound and consistent with its scenario-based analytical focus.

Therefore, the present research aims to identify the most suitable scenarios for the development of bioregions in Latvia using AHP. Specifically, the study seeks to determine which development scenario provides the highest overall added value in a sustainability context, based on expert evaluation across economic, social, cultural, and ecological dimensions.

2. Materials and Methods

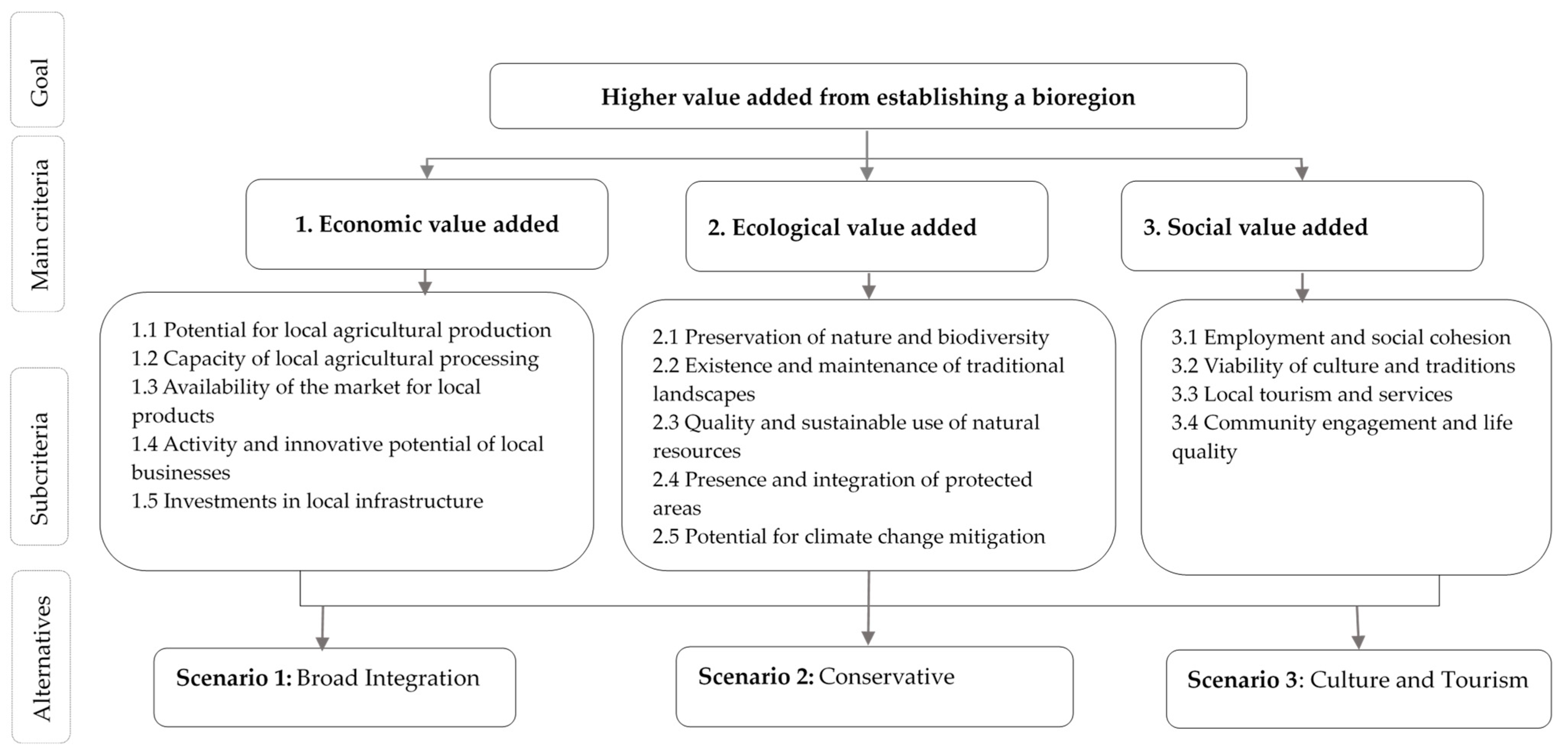

Based on the basic principles of the bioregional approach and their potential impact on territorial development, an AHP model was designed as part of the present research to determine which factors and scenarios generate the highest value added if forming bioregions in Latvia.

2.1. Expert Selection Criteria and Characteristics

According to the foundational AHP literature, priority is given to expert competence, experience, and sectoral diversity rather than to sample size [

26]. Previous studies applying AHP to territorial and development scenario assessment commonly relied on relatively small expert groups, typically comprising five to nine experts, particularly when the objective is to integrate diverse sectoral perspectives rather than to achieve statistical representativeness [

24,

25,

43]. Accordingly, the size of the expert group in the present study was determined by the scope of the analysis and the need to ensure balanced cross-sectoral representation. In line with these methodological principles, a structured expert selection procedure was applied in the present study.

To ensure methodological transparency and a balanced expert-based evaluation, experts were selected using predefined qualitative criteria. These included: (1) demonstrated professional experience in fields directly related to bioregional development (agriculture, regional policy, cultural heritage, community development, or agri-environmental research); (2) institutional involvement in policymaking, governance, research, or practical implementation relevant to territorial and sustainable development; (3) practical or analytical experience in strategy development, planning, or evaluation processes; and (4) the ability to represent distinct sectoral perspectives to ensure cross-sectoral balance within the expert group.

Table 1 summarises expert backgrounds at a level enough to demonstrate sectoral coverage and methodological relevance, while detailed professional histories are intentionally omitted to maintain focus on the evaluation procedure.

To ensure that the experts have a common understanding of how to rate the scenarios, the experts were familiarised with the scenarios, their main features, potential benefits and potential risks or limitations before starting to rate them. The experts were also provided with comprehensive information on the criteria and subcriteria and their roles at each level of analysis. The experts were also provided with methodological guidance on the principle of pairwise comparison in AHP, as well as on how to interpret numerical values in comparisons and how to rate the relevant significance of alternatives.

At the first stage, the experts made pairwise comparisons between three main criteria: economic, ecological and social value added. Each expert, based on their professional experience and understanding, identified which of the criteria was more relevant in a particular context. The results of pairwise comparisons were compiled into a comparative matrix, which was the basis for further calculation of the coefficients of significance. Next, individual pairwise comparison matrices were created for each of the basic criteria, with the experts comparing the subcriteria (e.g., for the economic criterion: local food processing capacity; for the ecological criterion: preservation of natural diversity; for the social criterion: employment, etc.). This approach allowed for a detailed assessment of which aspects in each of the dimensions were most significant within the respective criterion. At the next stage, the experts had to identify the extent to which each of the scenarios could contribute to meeting the respective subcriterion. For rating the scenarios, an individual pairwise comparison matrix was created for each subcriterion to rate the three identified alternatives: (1) broad integration, (2) conservation, and (3) culture and tourism (

Figure 1).

2.2. Characterisation of Scenarios, Criteria and Subcriteria

The Broad Integration Scenario (Scenario 1) envisages that the bioregional concept is implemented on a large scale, covering vast areas of high ecological and scenic value, as well as areas that have not been considered suitable for the introduction of the bioregional concept because of intensive economic activity or other reasons. This scenario envisages the creation of a new territorial governance model, covering various areas of Latvia with different socio-economic and environmental potential. Such an approach allows for the balanced development of sustainable agriculture and processing industries, strengthens local entrepreneurship, improves transport and logistics infrastructure and promotes the spread of innovations over a wider area. At the same time, the sustainable use of natural resources and the preservation of a quality living environment on a large scale are ensured as well. In a social context, this scenario envisages greater participation of local communities in the development of their territories, thus increasing employment opportunities and contributing to the economic security of the population.

The Conservative Scenario (Scenario 2) assumes that the bioregional approach is applied selectively in areas with significant ecological and scenic value, such as specially protected nature areas or areas with significant cultural landscapes. In the Latvian context, this includes, for example, nationally protected areas such as Gauja National Park, Kemeri National Park, and Slitere National Park, as well as culturally valuable landscapes shaped by traditional land use practices. Adapting the bioregional approach in this way reduces the initial impact on wider areas and reduces the likelihood of negative attitudes. By implementing this scenario as a pilot project, it is possible to identify potential challenges and risks, as well as to identify public support and economic efficiency. In ecological terms, this scenario minimises potential risks to biodiversity. However, the economic and social benefits under this scenario are most pronounced in the communities involved in the pilot projects.

Under the Culture and Tourism Scenario (Scenario 3), the bioregional approach is targeted at areas with a strong cultural and historical identity, traditions and tourism opportunities. In the Latvian context, this focus is aligned with national cultural policy priorities that emphasise the preservation of cultural heritage, the strengthening of regional cultural identity, and the sustainable use of cultural resources as a foundation for regional development, as defined in the Cultural Policy Guidelines 2021–2027 “Cultural State” adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia (2022) [

44]. The activities of the bioregion are aimed at preserving and developing local cultural values, crafts, gastronomy and unique living space through the tourism industry and the export of services. This approach is consistent with policy objectives promoting culture-led regional development, creative industries, and community-based cultural tourism. At the same time, the scenario envisages the participation and involvement of local communities in decision-making. Active involvement of local communities is recognised as a fundamental principle within Latvian cultural and regional development policy frameworks, especially in the context of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage and reinforcing local identity. From an economic perspective, this scenario creates development incentives for local businesses, various cultural projects and social initiatives. However, the ecological scenario contributes to the quality of historical environmental and cultural landscapes. Socially, this approach can strengthen the identity, cooperation and well-being of communities.

The scenarios put forward were rated according to the following criteria and subcriteria:

The main criterion of economic value added indicates the extent to which a bioregional approach to a given area can contribute to the development of the local economy by generating steady incomes, increasing employment, improving infrastructure and encouraging innovation. To perform a comprehensive assessment of economic value added, it is appropriate to divide the criterion into several detailed subcriteria. Such an approach allows for a more accurate analysis of individual aspects affecting development, as well as understanding their interaction with each other. Each subcriterion gives an in-depth insight into the importance of a particular factor in the context of the development of a bioregion. Next, the authors give characteristics of each subcriterion of economic value added.

- 1.1.

The production potential for local agriculture makes it possible to identify the capacity of the area to develop sustainable agriculture, especially organic or integrated farming.

- 1.2.

The local food processing capacity shows the extent to which opportunities have been or can be created in the area to process local agricultural commodities, adding value to them before they reach the consumer. It includes small-scale processing plants, cooperation, technological support and infrastructure.

- 1.3.

Market access for local products to identify how easily local products can reach consumers inside and outside the region. The rating considers the transport network and its quality, distance to markets, logistics infrastructure and availability of healthy products to consumers.

- 1.4.

The activity of local businesses and the innovation potential indicate how actively local businesses are involved in the creation of new products and services, attracting investments and introducing new technologies and networking.

- 1.5.

Investments in local infrastructure consider the extent to which infrastructure that directly supports the bioregional economy has been developed or is being planned in the area.

Ecological value added assesses how the bioregional approach to territorial development contributes to the protection, sustainable use, and quality improvement of natural resources within a given area. Since the principles for bioregions are based on the natural values of the area and the potential of ecosystems, high ecological value added means that a given area can become a clean and healthy environment for residents and visitors in the long term. The rating of ecological value added is important for a comprehensive assessment of the potential impact of the bioregional approach on nature protection and human economic activity. Ecological value added is identified by analysing a number of interrelated subcriteria that affect the overall ecological status, which is essential for sustainable development. Each of the subcriteria provides an in-depth understanding of possibilities for preserving and improving resources in the area.

- 2.1.

The conservation of nature and biodiversity indicates the extent to which natural ecosystems, habitats and species are preserved and protected in an area. Empirical studies in Latvia indicate that biodiversity indicators can vary over time within protected areas. For example, research on natural grasslands in Gauja National Park reports Shannon diversity index (H′) values ranging approximately from 1.8 to 2.5 in surveys conducted in 1998 and 2009, demonstrating measurable temporal and spatial variation in species diversity [

45]. In the present study, such indicators are used solely as illustrative empirical context and are not incorporated into the AHP-based scenario evaluation.

- 2.2.

The existence and maintenance of traditional landscapes show the level of preservation and maintenance of cultural and historical landscapes, which is an essential component of the identity of a bioregion.

- 2.3.

The quality and sustainable use of natural resources are characterised by the quality and usability of soil and the quality and availability of water resources, as well as the proportion of woodland and natural grasslands in the total area. This criterion indicates the state of the natural resources in the area, including the quality of soil and the quality and availability of water resources, as well as the proportion of woodland and natural grasslands, and assesses their sustainable usability for the development of the bioregion.

- 2.4.

The presence and integration of protected areas indicate to what extent the protected areas are integrated into the development and planning of the bioregion, the proportion of protected areas, the alignment of policy documents with nature protection regimes, the use of protected areas in the interests of society and the economy (e.g., green tourism).

- 2.5.

Climate change mitigation potential indicates the ability of an area to contribute to climate change mitigation through natural processes and proper management.

Social value added indicates the effect of the bioregion approach on a local community, its cohesion, quality of life, cultural identity and opportunities for participation. It shows the extent to which a bioregion helps to build strong, viable communities that support both ecological and economic sustainability. The role of social value added lies in its ability to balance economic, environmental and human interests, giving development a human dimension based on societal needs. An assessment of it helps to understand how the bioregional approach affects employment opportunities, social cohesion, the preservation of culture and traditions, the development of local tourism and services, as well as community engagement and the quality of the living environment. These interlinked aspects contribute to the resilience of local communities and the long-term attractiveness of a region. Assessing the impact of social added value requires complementary subcriteria, which make it possible to reveal more accurately how specific factors shape and affect the development and quality of life of a community.

- 3.1.

Employment and social cohesion. Employment is perceived as the basis of social well-being: less unemployment, more social cohesion and residents staying in the region. Social cohesion means the internal cohesion of society and its ability to cooperate in achieving common goals. It is people’s sense of belonging to their community and mutual trust that help them solve problems together and develop their territory.

- 3.2.

The viability of culture and traditions is characterised by how the bioregional approach helps to preserve and develop local traditions and cultural and historical values and inspires future generations. It involves local values and identities, preservation and development of local cultures and traditions and involvement of new generations and learning opportunities in the bioregional context.

- 3.3.

Local tourism and services are assessed in terms of how the bioregional approach contributes to the growth of tourism and services, thus making socio-economic contributions and strengthening the community’s capacity to provide authentic tourism experiences based on the local environment and culture.

- 3.4.

Community involvement and quality of life (participation and quality of the living environment) involve assessing community involvement and initiatives, as well as improving the quality of life.

2.3. Pairwise Comparisons and Consistency Assessment in AHP

The experts gave individual ratings by filling in a specially designed questionnaire in Excel format, which included several matrices for comparing pairs according to the hierarchical structure of AHP. Each matrix was constructed as a square n × n matrix, where n was the number of elements to be compared at the given level. For example, a matrix of 3 × 3 was created in the case of the main criteria. Representative aggregated group pairwise comparison matrices, together with the corresponding normalised values and CI/CR calculations, are provided in

Supplementary File S2. The research used AHP to determine the weights of criteria and subcriteria that are essential for identifying the suitability of areas for the creation of bioregions. AHP was applied to perform prioritisation and analyses, which are essential for deciding which areas are most suitable for inclusion in bioregions. It helps to make informed decisions based on a multidimensional analysis that includes biological, agricultural, environmental, social and economic factors.

The experts gave their ratings of the relative significance of each criterion over another on a nine-point scale, where 1 meant equal significance and 9 meant absolute predominance (see

Table 2).

Accordingly, the reverse value was assigned to the second element of the comparison. In the main diagonal of each pair comparison matrix, where the elements were compared with themselves, the value was always 1, since the relative significance of any element relative to itself was the same. A detailed description of the AHP analysis methodology, including calculation procedures and consistency assessment steps, is provided in

Supplementary File S1—Detailed Methodology and Calculation Steps of the AHP Analysis.

Since there was a possibility that the ratings might be contradictory (inconsistent), the pair-comparison matrices were normalised, and their internal coherence was checked by a coherence test yielding a coherence ratio (CR). The elements of each column of the matrix were normalised by dividing each element by the sum of the elements in that column. After the normalisation, the arithmetic mean of each row was calculated, which indicated the relative weight of the respective element. The weight vector (w) calculated indicated the relative significance of the compared elements at a given level of the hierarchy and was used in further analysis, both in rating the scenarios and in performing an overall synthesis of the results. According to Saaty (1980) [

26], the developer of AHP, the CR must be less than or equal to 0.1 or 10% in order for comparisons to be considered methodologically acceptable, but if this limit is exceeded, a review of the ratings given by experts is required. At the same time, the scientific literature documents that in applied studies in cases where evaluations from multiple independent experts are analysed, a more flexible approach to the interpretation of the consistency ratio (CR) may be justified. For example, Belton and Stewart (2002) [

24] argue that in the context of multi-criteria decision-making, methodological consistency should be assessed in balance with the complexity of the decision-making process and the multidimensional nature of expert judgement. Similarly, Ishizaka and Nemery (2013) [

25] emphasise that in group decision-making within the AHP framework, minor deviations in consistency may be acceptable if they are critically examined and if the final results are interpreted with caution. In the field of energy and sustainable development planning, Pohekar and Ramachandran (2004) [

43] demonstrate that AHP is frequently applied in practice using relatively small expert groups and complex criteria structures, where methodological flexibility is necessary to preserve the practical usefulness of the analysis. In exceptional cases when the pairwise comparison matrix is larger or when evaluations from several independent experts are analysed, the permissible CR threshold may be increased to 0.20 (20%), while maintaining a critical assessment of the degree of consistency [

46,

47,

48]. Consequently, this approach is not in conflict with the fundamental principles of the AHP methodology but is consistent with applied practices described in the international literature, maintaining a balance between methodological rigour and the realities of empirical research. Based on this literature, the increased CR threshold to 0.20 (20%) in the present study was applied only as an exception, following a detailed analysis of inconsistencies and a logical justification of the pairwise comparisons provided by the experts.

The present research, taking into account the number of pairwise comparison matrices, as well as the fact that the ratings were given by a number of independent experts, applied a more flexible approach to the permissible coherence ratio (CR):

If CR ≤ 0.10, comparisons are considered coherent and are used without further verification.

If 0.10 < CR ≤ 0.20, an expert’s rating was re-discussed, paying attention to the contradictions identified. If the expert reasonably justified their vision and the logic of the comparison, the respective rating was considered acceptable and included in the subsequent analysis.

If CR > 0.20, an expert was asked to redo their pair comparison matrix to find discrepancies and reach greater coherence.

Such an approach allowed the authors to maintain a balance between methodological rigour and practical flexibility, thus ensuring the quality of the data and at the same time considering the specifics of expert involvement.

Since each pairwise comparison matrix was filled in individually by the experts, the ratings were combined to obtain a single group rating for each unit of the hierarchy. According to the methodological principles of AHP [

26], the combination involved calculating the geometric mean for each pairwise comparison, which was the most commonly used method to consolidate the opinions of independent experts. This method made it possible to maintain the multiplicative structure of pairwise comparisons while at the same time equalising the effects of individual ratings [

29].

As a result, a single matrix of group comparisons was created, which served as the basis for calculating criteria weights and evaluating the scenarios. After the combined matrix was created, a CR for a group was calculated to assess the coherence of the overall ratings. Although the calculation of a CR is not mandatory in cases of group decisions, several authors recommend it [

29], as it provides an opportunity to identify whether experts have been sufficiently coherent with each other in their ratings and allows for the timely identification of significant contradictions. A similar approach has also been applied by national researchers who had analysed the coherence of group results based on a CR for combined matrices [

37,

38].

The final ratings of the scenarios were found by employing the weighted sum method [

21]. The overall rating for each alternative scenario was calculated by multiplying the relative weight of each subcriterion (derived from subcriteria comparisons) by the rating of the respective scenario in that subcriterion, and the multiplications were then added up, while taking into account the weights of the higher-level (main criteria). As a result, a comparable overall priority vector value was found for each scenario, indicating its relative suitability for establishing bioregions in the context of the hierarchy developed by the present research. Given that in the scientific literature, percentages are often used to show the results of an AHP analysis [

49] in order to facilitate the perceptibility of the results and to compare the significance of alternatives to a wide audience, the authors also used percentages to interpret the results. Since priority vector values are relative quantities that are often used only for intermediate weight calculations, the presentation of the final results in terms of percentages facilitates their comparison and interpretation, thus making the analysis results also accessible to users without in-depth knowledge of mathematics or multidimensional data analysis.

3. Results

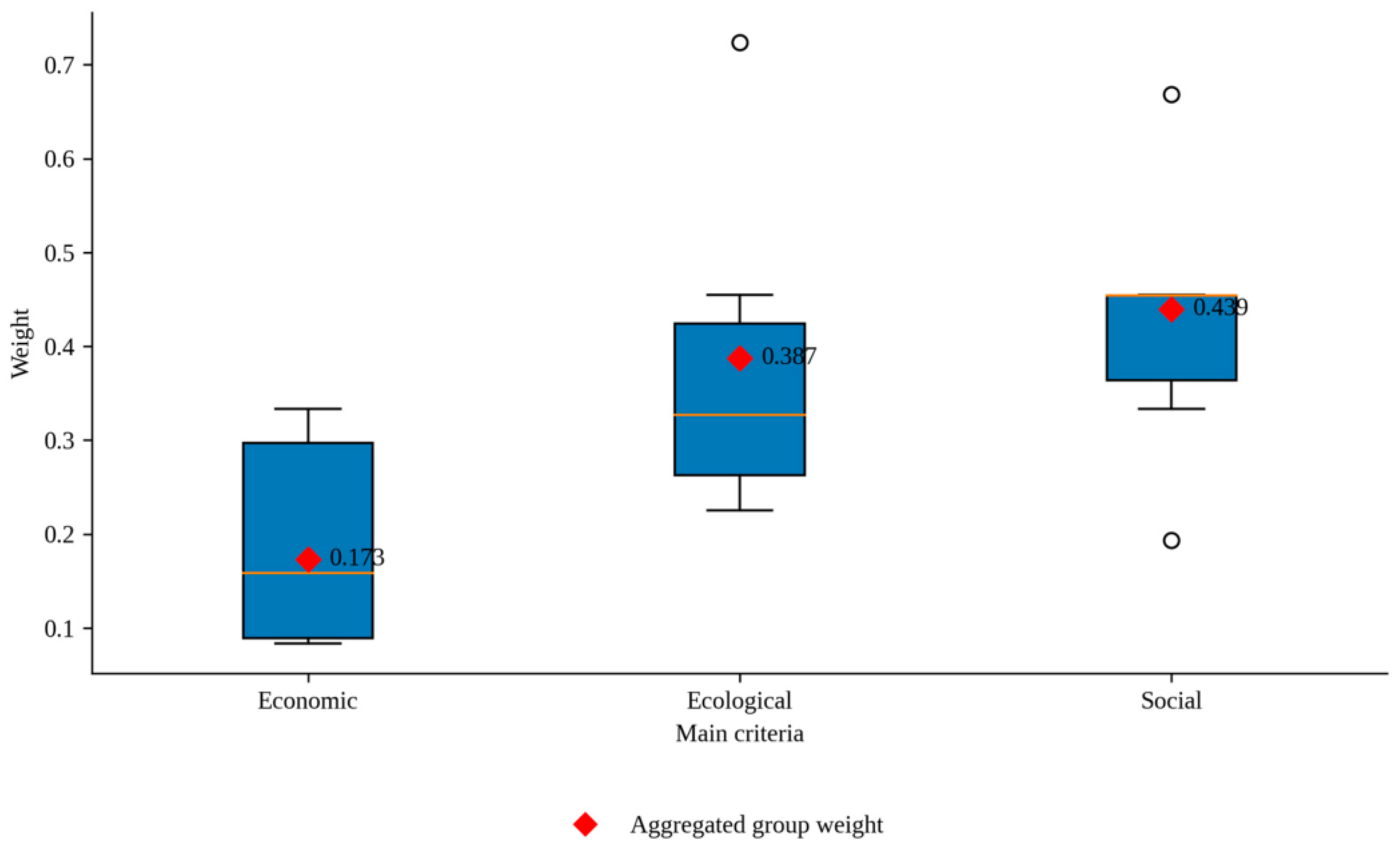

After combining and processing all the expert ratings by applying AHP (

Appendix A,

Table A1), the priority vectors (weight) of the main criteria were broken down in terms of the kind of value added as follows: economic value added 17.3%, ecological value added 38.7% and social value added 43.9% (

Figure 2). The aggregated expert group calculations underlying these results are reported in

Supplementary File S2.

The analysis results clearly indicate that, in the opinion of the experts, the social and ecological aspects are the most significant driving forces for strategic development. Although economic factors are considered significant, they play a complementary rather than a dominant role in the context of the present research. Such a trend is fully in line with the principles of sustainable development because, in the long term, priority is given to the well-being of society and the preservation of the environment.

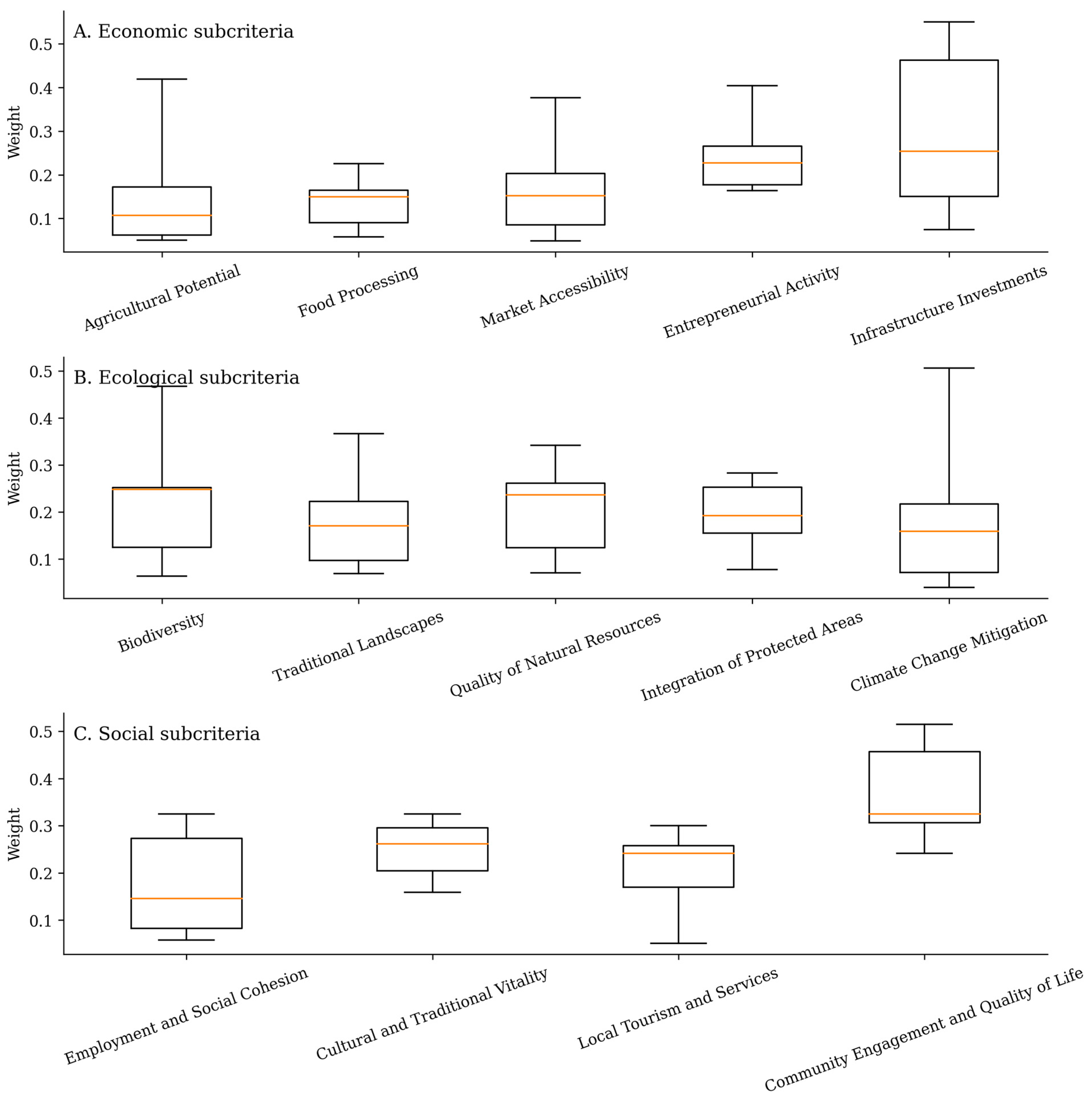

At the level of the subcriteria (

Figure 3), there are different priorities, thereby revealing which specific indicators determine the significance of each dimension. For example, regarding economic value added, infrastructure investments (28.7%) and entrepreneurial activity (27.5%) were rated as the most significant, together accounting for more than half of the significance of this group (

Appendix A,

Table A1). Other indicators: market availability (16.0%), food processing (14.5%) and agricultural potential (13.3%) were less significant. Similar trends could be observed in relation to ecological and social subcriteria, with individual elements dominating and determining the main pathway in which measures could make the largest contribution. Regarding ecological value added, the highest significance was given to biodiversity (22.8%), integration of protected areas (21.2%) and quality of natural resources (21.2%). If combined, they accounted for more than two-thirds of the overall ecological priority, thereby stressing the need to preserve and integrate natural areas and maintain their quality. A slightly smaller but still significant proportion was held by traditional landscapes (18.7%) and climate change mitigation (16.1%), demonstrating the significant role of maintaining landscape identity and climate policy elements in maintaining a sustainable environment.

It is also important to identify the global weight of the criteria, as it reveals the real impact of each factor on the choice of the final scenario and helps to identify which elements in the strategic planning process are prioritised in order to achieve the highest return from the bioregional approach. A high global weight means that a subcriterion has a significant impact on the assessments of scenarios, even if its relative weight is not the highest within its group. The results of the AHP analysis revealed that the main criterion of social value added had the highest weight; therefore, the moderately significant subcriteria (in terms of weight) in this group also had a significant global impact (

Figure 3).

According to the combined expert ratings, the criteria “Community involvement and quality of life” and “Viability of culture and traditions” (social value added), as well as “Biodiversity” (ecological value added), had the highest global impact. This means that these aspects have been crucial for the experts in their choice of the final scenario that could provide benefits for society, the environment and long-term resilience to economic and social changes. Accordingly, strategic plans at both the local and national levels should be designed taking into account the dominant role of these elements, thereby integrating them as key priorities in regional development programmes, policy documents and investment plans.

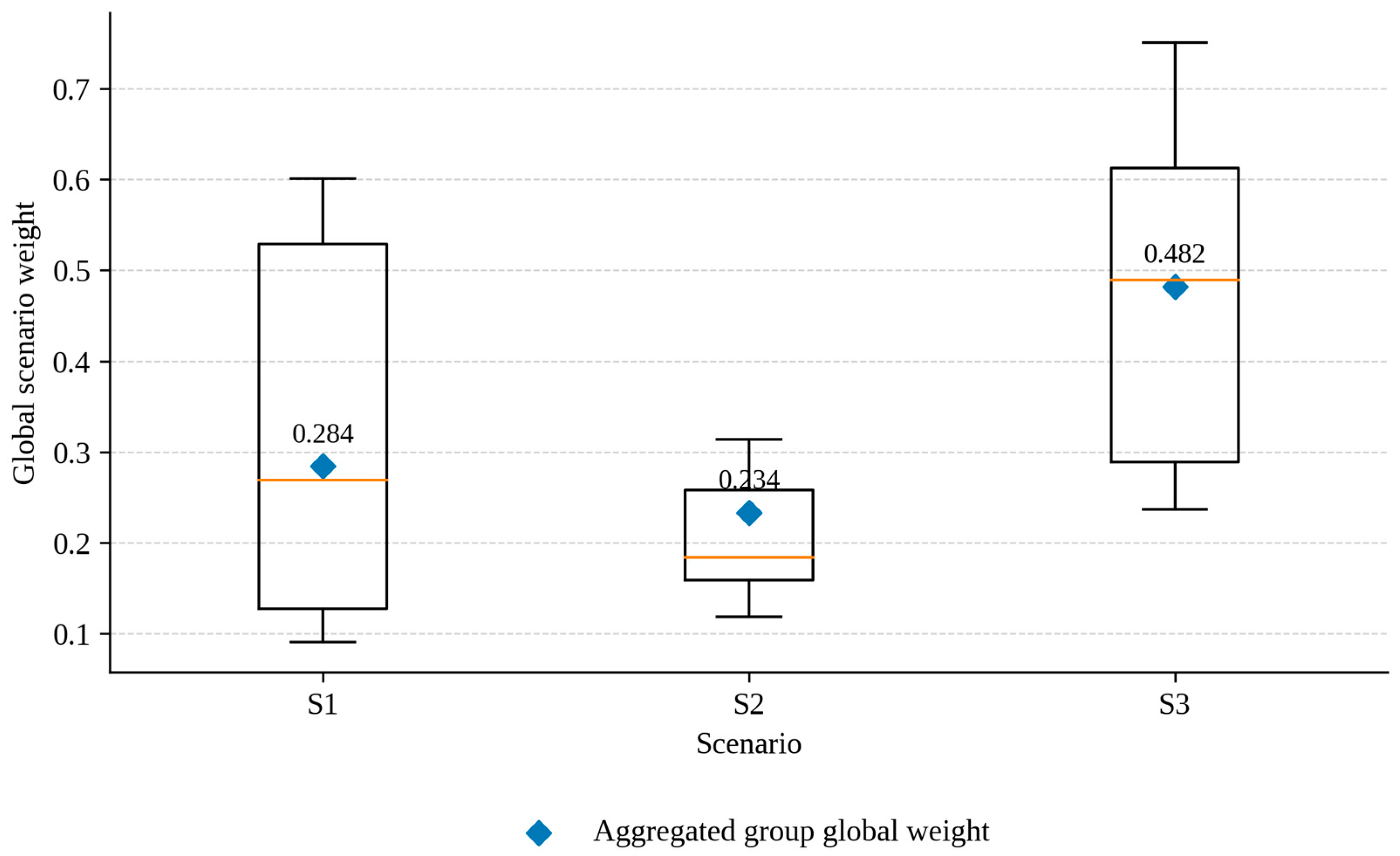

The analysis assessed three alternative regional development strategies based on the implementation of the principles of the bioregional approach to ensure a coherent and sustainable use of socio-economic, ecological and cultural resources. The Broad Integration Scenario gained a priority weight of 0.284, or 28.4%; the Conservative Scenario’s weight was 0.234, or 23.4%; and the Culture and Tourism Scenario gained the highest relative significance with a weight of 0.482 (

Figure 4). The analysis results revealed that it was the cultural and tourism approach that most fully reflected the essence and potential of the bioregional approach in achieving the long-term development goals of a region, combining the social and ecological dimensions with the economic opportunities provided by the development of the cultural and tourism industries.

An analysis of the global weights of individual priority vectors rated by the experts for the scenarios showed that each expert’s view of priorities varied slightly; however, the prevailing trend was persistent, with most of the experts giving the highest ratings specifically to the Culture and Tourism Scenario. In some cases, the experts were more inclined to support the Broad Integration Scenario, giving higher global weights to economic criteria, yet the differences were not enough to change the overall result.

It should be noted that the range of expert ratings was relatively wide, especially for the first and third scenarios (

Appendix A,

Table A2). This means that the expert opinions were polarised, with some experts rating a scenario very high, whereas others, on the contrary, very low. An average of 0.32 (scenario 1) and 0.48 (scenario 3) indicated a compromise between the opposing views. A relatively high consensus of expert opinions was observed for scenario 2, which was rated in a moderately narrow range.

To identify the reliability of the final results and the coherence of the expert ratings, it is essential to identify the dispersion of individual expert ratings (global weights) and their coherence ratios.

The test of the logical coherence of ratings using the coherence ratio (CR) showed how coherently experts have followed the rating logic when comparing criteria and subcriteria in pairs. All calculated CI and CR values for each individual expert evaluation, as well as for the aggregated expert group evaluation, are presented in

Appendix A,

Table A3 and

Table A4. At the level of the main criteria, the CR was found at 0.00069, which was well below the internationally accepted permissible threshold of 0.1. There were nuanced differences in the weight distributions of global priority vectors by individual experts, yet they were based on consistent and coherent ratings, as evidenced by the very low CR. Although the experts assigned different meanings to some criteria or scenarios, the approach to comparing them remained uniform and coherent. This ensured that the combined expert result was not contradictory and reflected a common view of priorities.

It should be noted that the highest rating of the Culture and Tourism Scenario by the experts was in line with the recognition expressed in expert interviews that the bioregional approach was most fully revealed in the social dimension, which includes cultural and tourism aspects. Both the interviews and the ratings of the scenarios suggested that through the prism of culture and tourism, social factors could directly contribute to economic value added, e.g., revenues from tourism, and increase sales of locally produced agricultural products, thereby contributing to economic activity in the region. However, economic activities, in particular the development and expansion of infrastructure, could have a positive impact on the quality of the environment and landscapes, and, taking into account the interaction of the elements, the quality of life would increase in the long term. This bioregional approach is also fully consistent with the theory of cultural determinism analysed in theoretical research studies [

50,

51], thereby emphasising that success in regional development is strongly linked to the values and social capital of a local community and experience in bioregional development in Europe.

4. Discussion

The development of bioregions is based on socio-economic and ecological theories intertwined with various aspects of regional policy. The formation of bioregions is affected by various factors, and it is not a uniform process and depends on the economic, social, cultural and environmental features of the area, as well as the values of the community. According to leading researchers focusing on the concept of bioregions, Salvatore Basile, Cesare Zanasi and Jostein Hertwig [

9], the reasons for the creation of a bioregion could be influenced by societal initiatives, territorial resources, economic motivation or environmental motivation. Based on some research studies [

12,

16,

28], three conceptual categories of bioregions can be distinguished, thus reflecting the different prerequisites for the creation of bioregions, the potential of environmental aspects and development pathways, while providing a potential theoretical framework for further development and comparison of the scenarios in Latvia.

Comparative European experience further confirms that bioregional development models vary significantly across countries. For example, in Spain, bioregional and ecoregional approaches are often embedded in energy transition strategies, biosphere reserve governance and bioeconomy policies, emphasising territorial self-sufficiency and multi-level coordination [

52,

53]. In contrast, Italian bioregions are more strongly rooted in organic farming networks and bottom-up agricultural initiatives, while other European cases demonstrate more flexible, planning-oriented and policy-driven implementations adapted to national institutional contexts [

54,

55]. These differences highlight that bioregional development cannot be transferred as a fixed model but must be adapted to local governance structures, policy frameworks and territorial specificities, which is particularly relevant for the Latvian context.

Structural transformation bioregions are areas where the concept of bioregions is introduced as a tool for territorial development to promote structural change in a vast area having high ecological and landscape values. Covering vast areas with various governance models, structural transformation bioregions serve a new governance and development model that promotes sustainable development, societal engagement and economic growth. Such bioregions are designed to transform rural areas structurally, with the aim of developing sustainable agricultural and manufacturing industries steadily, strengthening local entrepreneurship, improving infrastructure and encouraging the application of innovation. However, it should be acknowledged that structural transformation of bioregions may also entail potential environmental risks if territorial development is pursued on a large scale without sufficient ecological constraints. Large-scale infrastructure development, production intensification, or increased tourism flows may intensify pressure on biodiversity and landscape structure, particularly in areas with a high concentration of natural values. Such trade-offs have also been identified in European practice. For example, the Biovallée initiative in the Drôme region of France, often cited as a successful case of structural transition in the fields of bioeconomy, renewable energy, and organic agriculture, has also been analysed as a case where rapid territorial transformation requires strict spatial planning and ecological impact control in order to prevent land use conflicts and increased pressure on ecosystems [

54]. Similarly, in the Sörmland region of Sweden, where bioeconomy and regional sustainability strategies are implemented at a broad territorial scale, research indicates that integrated policies linking nature conservation, agriculture, and regional development are essential to prevent biodiversity loss risks that may arise from production intensification and infrastructure expansion [

10]. The scientific literature emphasises that, in such cases, clear spatial planning and adaptive governance are required to ensure a balance between economic development and ecosystem resilience [

52,

55].

Bioregions for the preservation and development of ecological values cover areas with a high concentration of natural and landscape values, e.g., protected areas where production or agricultural activity is limited. The concept of bioregions is applied to preserve and protect the values by reaching a balance between economic activity and environmental resilience. It should be taken into account that the limited area of a bioregion means that its potential economic and social benefits are manifested in the particular region, but at the same time it also serves as an opportunity to familiarise the wider public with the concept of bioregions and the potential benefits and risks, so that in the future it would be possible to reorient the public towards the structural transformation model and development in wider areas. Although this study did not include a quantitative assessment of economic impacts, international experience suggests that the proportion of protected areas within a region can constitute a significant indirect economic resource by supporting ecotourism, recreational services, and place-based branding. European studies indicate that in regions with a high share of protected natural areas, economic contributions are often realised through the service sector and long-term regional attractiveness rather than through direct growth in production activities [

53]. This indicates that bioregions oriented toward ecological protection play an important role in a balanced regional development model, even when their economic impacts are not immediately measurable.

Bioregions for cultural and landscape development cover areas where the creation of a bioregion is based on local cultures and identities and tourism resources. Bioregions are mostly created in areas where the initial potential represents strong cultural and historical values in business, high tourism potential and a strong connection of the identity of residents with the area. Organic food, crafts, local food traditions and environmental and landscape values are integrated into a territorial brand that serves as the basis for the sustainable development of the region. At the same time, the literature emphasises that development driven by culture and tourism may also generate negative externalities, particularly in cases of increasing tourism intensity. Excessive tourism development can contribute to the commodification of culture, the homogenisation of local traditions, and growing pressure on the quality of life of local residents. Such risks have been documented in regions where cultural heritage is utilised primarily as an economic resource rather than as a living component of community identity [

56,

57]. Therefore, the sustainability of culture- and landscape-oriented bioregions is closely dependent on balanced tourism governance, active involvement of local communities, and clearly defined mechanisms for regulating visitor flows.

The high global weight assigned to the subcriterion community participation and quality of life reflects the internal logic of the bioregional development scenarios rather than a general social preference. In the Latvian context, bioregional development is closely linked to local community initiatives, public support, and the active involvement of residents in territorial development processes. Empirical studies demonstrate that public participation enhances the effectiveness and sustainability of regional development and environmental governance by integrating local knowledge and strengthening the legitimacy of decision-making processes [

58]. In the AHP analysis, this subcriterion achieved a high global impact because it significantly influenced the evaluation of scenarios across multiple criterion levels, particularly within the Culture and Tourism Scenario. Quality-of-life aspects are closely linked to landscape quality, ecosystem services, cultural heritage, and tourism attractiveness [

56,

57]. In the Latvian context, these factors constitute a significant resource base for bioregional development. Accordingly, the high importance assigned to this subcriterion reflects the experts’ assessment that community-based and socially supported development pathways are essential for the resilience and long-term sustainability of bioregions, while maintaining a balance with ecological and economic considerations.

At the same time, these results should not be interpreted in terms of cultural determinism, as cultural and social factors in this study are considered as enabling conditions for development rather than as autonomous or self-sufficient drivers. The literature emphasises that community participation alone does not guarantee successful territorial development without adequate institutional support, balanced representation, and clearly defined governance mechanisms. Therefore, the high global weight assigned to this subcriterion should be interpreted as a potential whose realisation depends on governance capacity and the quality of cooperation across different levels [

58].

In Latvia, the concept of bioregions is relatively new, and its practical implementation is still being adapted to local development conditions. Research highlights the need for closer coordination and cooperation in territorial development processes in order to foster the emergence of bioregional initiatives [

27]. The potential of traditional food production, hospitality and place-based tourism is significant [

59]; however, its realisation is closely linked to active community involvement and a bottom-up approach. From a policy perspective, this implies the need for integrated support measures that connect cultural heritage, local food value chains and tourism services at the municipal and regional levels, while preventing excessive tourism pressure and ensuring long-term community benefits. At the same time, the literature emphasises that the success of bioregional development depends not only on the activation of local initiatives but also on institutional capacity and the consistency of policy instruments [

58]. In the Latvian context, this underscores the need for a clear distribution of responsibilities and coordinated action between municipalities and state authorities. Studies on local agri-food systems and rural tourism further indicate that the risks of greenwashing may undermine consumer trust and limit the socio-economic benefits of bioregional initiatives [

60]. Conversely, organic farming, short food supply chains and resilient local food systems can contribute to sustainable territorial development when supported by targeted and coherent policy frameworks [

61,

62]. From a policy-planning perspective, the principles of the bioregional approach should be more systematically integrated into regional development and spatial planning documents through the use of pilot projects and thematic support instruments [

28]. Municipalities play a key role in facilitating community cooperation, while at the national level, improved coordination between agricultural, environmental and regional development policies is necessary to ensure the long-term viability of the bioregional approach. However, identifying the development benefits of an area helps to encourage cooperation between local governments and communities aimed at the development of the area.