1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation of the Study

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a central element of the globalization process, one that is not limited merely to a simple transfer of capital but also facilitates the transfer of goods, services, technologies, information, and knowledge between different economies. After the 1980s, the flow of foreign direct investment worldwide began to increase considerably. Thus, global FDI flows increased from

$50 billion in the early 1980s to

$1.51 trillion in 2024 [

1]. This spectacular growth can also be explained by the following potential positive effects that FDI has on the economies of host countries: increasing the stock of capital and knowledge, introducing new technologies, and, implicitly, boosting labor productivity [

2].

The theoretical foundations for understanding the relation between FDI and economic development are driven from multiple schools of economic thought, each offering different but complementary insights into the transmission mechanism of FDI’s effects on the host-country development and growth. FDI is considered the most important contemporary factor for the sustainable development of any national economic system. In traditional neoclassical models (exogenous growth models), FDI was treated as a factor contributing to the growth of the capital stock, allowing the economy to reach a higher level of output per capita. Keynesian and post-Keynesian (neo-Keynesian) growth theories consider investment to be the main driver of economic growth through investment multiplier and accelerator mechanisms. The new endogenous growth models, developed notably by P. Romer, R. Lucas, G. Grossman, and E. Helpman, argue that investment in technological development and human capital forms the basis for economic development and growth [

3].

Building on these theoretical insights, it is important to distinguish between economic growth—a quantitative measure that typically captures changes in real GDP or GDP per capita—and economic development, a broader qualitative concept that incorporates structural transformations, institutional improvements, and enhanced quality of life of the entire population. Sustainable economic development requires that growth be accompanied by productivity improvements, higher value-added activities, export diversification, technological development, and institutional empowering. All these are aspects that FDI can potentially contribute to. Conceptually, there is a clear distinction between economic growth and economic development. Economic growth has a quantitative connotation, usually referring to the value of GDP (gross domestic product) recorded in an economy over a specific period compared to the GDP value recorded in a previous period (after removing the effects of inflation). Economic development has a more qualitative valence, reflected in the qualitative changes occurring within the economic processes of an economy, which lead to enhanced economic performance and an improved quality of life for the community. Economic development also implies economic growth, but not all economic growth constitutes economic development—only that which leads to structural-qualitative changes in the national economy and improvements in people’s quality of life.

We built our study on the distinction between growth and development conceptual framework, focusing on economic sustainability dimensions, like productivity growth, export competitiveness, structural transformations, and institutional capacity. Although we acknowledge the importance of environmental sustainability, since our analysis does not take into account proxies for it, due to the lack of availability of data, we address these aspects in the policy recommendations.

Romania’s economic trajectory over the 2003–2023 period represents an interesting case study for analyzing FDI-growth relationships in transition economies. Romania experienced profound structural transformations shaped by the EU integration, global financial crisis, and pandemic negative effects. Understanding this context is important for our interpretation of the empirical results and for generating policy recommendations. We can divide our sample period in five principal phases related to the evolution of Romania’s development. In phase 1, between 2003 and 2006, being a pre-EU ascension period, Romania had to make some institutional reforms to meet the EU ascension criteria, including judicial improvements, anti-corruption measures, and regulatory harmonization. These measures helped at creating a more predictable investment climate, attracting foreign direct investment. In phase 2, between 2007 and 2008, the EU ascension on 1 January 2007 helped at eliminating the remaining trade barriers, ensured free movement of capital and labor, and facilitated institutional reforms through EU governance mechanisms. However, in phase 3, between 2009 and 2010, the financial crisis hit Romania severely and, besides GDP contraction and unemployment increasing, the FDI inflow also collapsed, although the FDI stock remained resilient, continuing to grow. This aspect is important for our analysis because it reflects the need to disentangle the FDI stock and FDI flow’s influence on growth and development. In phase 4, between 2011 and 2019, the largest phase in our sample, Romania’s development was characterized by a post-crisis recovery, although it witnessed the spillover effects of the Eurozone crisis. In this period, Romania gradually recovered, although the political instability made the recovery slowly. In the last phase, phase 5, between 2020 and 2023, Romania was again affected by another crisis, this time not an economical one, but a medical crisis, generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the economy decreased sharply and there were many changes that the economic sectors had to face, such as severe supply chain disruptions and demand collapse, implementing remote work and accelerating the digitalization adoption. However, although FDI inflows decreased, the FDI stock remained resilient, a pattern that was also observed in the financial crisis.

The analysis of the Romania’s development over the period 2003–2023 highlights the focus of our study on distinguishing FDI stock and flow effects and deriving sustainability-oriented policy recommendations.

The objective of this paper is to analyze the impact of FDI on sustainable development in Romania, over the period 2003–2023. Our purpose is to capture the different effects of FDI stock and FDI flows to emphasize which of the two matter more for sustainable growth and to analyze the extent to which labor productivity and trade are transmission channels for the FDI effects.

The contribution of our study spans in four directions. First, we include both FDI stock and flow in the same model and study the comparative effects of both for Romania’s growth. Second, we consider a large sample that covers the COVID-19 pandemic and the after-recovery period. Third, for our empirical framework, we take into account the labor productivity growth rate, rather than its levels to capture dynamic productivity; furthermore, we address multicollinearity between FDI measures and trade variables and extensively document our model selection rationale and the lag structure specification. Fourth, our paper contributes to the literature regarding the FDI’s effects on sustainable growth by using economic sustainability dimensions that we can measure in the empirical analysis and addressing environmental and social dimensions of sustainability in the policy recommendations based on our study.

1.2. Literature Review

In recent years, several authors have attempted to analyze the effects of FDI on host economies in general, and on their economic growth/development in particular. Most of them have concluded that FDI leads to economic growth for the host countries [

4]. This paper aims to determine the impact of FDI and other economic variables (imports, exports, and growth rate of labor productivity per employed person) on economic growth in Romania, analyzing data related to these variables for the 2003–2023 period.

Historically, the study of the relationship between FDI and economic growth has been dominated by many economic theories, each of them emphasizing different transmission mechanisms of FDI impact towards host-country development. Neoclassical growth theory [

5,

6] documents the effects of FDI on growth, but only on a temporary basis through its impact on capital accumulation. In addition to this, endogenous growth theory [

7,

8,

9,

10] documents technology transfer, human capital accumulation, and innovation spillovers as transmission mechanisms of FDI’s effects on growth. A recent study [

11] argues that productivity improvements and innovation better shape the impact of FDI on growth than the simple capital accumulation. Modern endogenous growth theories emphasize the positive effect of FDI on the economies of host countries. Empirical studies, such as the one conducted by [

4], support the fact that FDI fosters development and economic growth, with the positive effect often being more pronounced in developing countries. Thus, it has been empirically shown that FDI has a greater impact on economic growth in less developed countries, where there is a higher demand for investment and advanced technologies, compared to developed countries [

12]. In a comprehensive review of these theories, Ref. [

3] outlines that the effects of FDI on growth depend on both the supply side (technology transfer, productivity) and demand side (investment multipliers, aggregate demand). Coupled with this evidence, Ref. [

13] highlights the following five main transmission mechanisms of FDI effects towards growth: capital accumulation, technology transfer, human capital development, competitive pressure that stimulates host-country firm efficiency, and backward and forward linkages with domestic suppliers and customers.

A substantial body of research focuses on the distinction between FDI stock and FDI flow and the effects of the two concepts on economic growth. Capturing the cumulative value of foreign investments in the host country, FDI stock highlights the long-term presence and commitment of foreign affiliates, while FDI flow captures short-term confidence and sentiment, being representative for the annual inflows of foreign capital. Regarding the empirical illustration of this distinction, Ref. [

14] presents significantly larger effects of FDI stock on growth than using FDI flows, underscoring that accumulated foreign investments matter more than annual flow variations. Also, Ref. [

15] found that, for CEE transition countries, FDI stock has positive and long-run effects, while FDI flow proved to have no significant impact in pooled specifications. Moreover, the importance of FDI stock for sustainable growth is also emphasized in its resilience in times of crisis [

16] and its effects on FDI quality (technology intensity, R&D content, and skill requirements), which matter more for economic growth than FDI quantity, as shown in [

12]. Recent evidence of [

17] emphasizes the endogeneity between growth and FDI. The study demonstrates that, while growth triggers immediate FDI flows, the accumulated FDI stock is a significant determinant of long-term growth, validating the existence of virtuous circle dynamics in the FDI–growth nexus. This evidence is also supported by [

18].

Building on these aspects from the existing literature, we consider that one of the main contributions of our study is the inclusion of both FDI stock and FDI flow in the analysis and capturing their relative impact on growth, since the historical analysis of the Romanian economic context shows volatile FDI flows, but relatively resilient FDI stock during both financial crisis and pandemic.

The issue of the factors that shape the relation between FDI and growth have received considerable attention in recent years. Evidence shows that the benefits of FDI are not automatic. Instead, they depend on a country’s “absorptive capacity”—its ability to use foreign capital. Studies by [

19,

20] suggest that FDI boosts growth if the host country has a well-educated workforce and a developed financial system. Recent studies also emphasize that good infrastructure and a stable economy are necessary to turn FDI into economic growth [

21]. Furthermore, the “technology gap” matters: if foreign technology is too far ahead of what local companies use, it becomes difficult for them to adopt foreign investments [

22]. The quality of a country’s laws and government also determines how well FDI works. Research highlights that when a country has strong institutions (low corruption and clear business rules), FDI is much more effective at positively impacting economic growth through technology transfer [

23], while countries with weak institutions benefit less from FDI spillover effects, even with large FDI presence.

Beyond domestic conditions, a significant body of research examines how FDI influences a country’s growth through its impact on international trade and global integration. The relationship between FDI and trade is a central pillar of the “export-led growth” hypothesis. Research suggests that FDI does not just provide capital but acts as a bridge to global markets. This happens through “export platform” investments, where foreign firms set up local facilities to serve international customers and by integrating local businesses into global supply chains [

24]. Empirical evidence shows strong FDI-export complementarities, working together to drive economic growth, particularly when investments involve building new facilities rather than just acquiring existing ones [

25]. In the Romanian context, this link is significantly strong, as shown in [

26], which outlines that FDI also plays an important role in the re-specialization of developing economies and in increasing export potential. While exports provide clear benefits that are proven empirically, the evidence on the import–growth relationship is mixed. However, in our initial analysis, we include both export and import because we consider it important in understanding the Romania’s growth path.

In addition to trade dynamics, labor productivity serves as a primary channel through which foreign investment translates into long-term economic development. Foreign firms enhance productivity by introducing advanced technology, superior management practices, and specialized workforce training, while driving local competitors to innovate. Research by [

27,

28] confirms that in transition economies like the one in Romania, these benefits often spread through “backward linkages”, where foreign firms provide technical support to their local suppliers. While most studies look at static productivity levels, our analysis specifically uses the labor productivity growth rate to capture dynamic efficiency gains. This approach allows us to identify whether a continuous acceleration in productivity, rather than just a one-time improvement, is what truly drives economic growth.

The empirical literature surrounding Romania’s FDI–growth relationship must be contextualized within the broader transition dynamics of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where regional benchmarks provide a critical framework for evaluating whether observed patterns are country-specific or characteristic of the post-transition experience.

The role of FDI as a catalyst for economic convergence in CEE is well documented. Ref. [

29] demonstrates that FDI contributed between 30% and 40% of GDP per capita growth in countries like Romania and Poland, while ref. [

28] highlights how foreign affiliates transformed CEE countries into export platforms for the European market. However, the efficiency of FDI is influenced by some factors that shape the relation between FDI and growth. Ref. [

30] finds that institutional quality acts as a critical mediator, where institutional volatility can significantly dampen the FDI–growth nexus. Central to the regional narrative is the distinction between FDI stock and flow. While [

14,

31] observe that capital flows are highly sensitive to cyclical shocks, they find that FDI stock reflects accumulated structural factors that provide resilience during crises. This finding aligns with the foundational work of [

32,

33] regarding long-term technology transfer. Furthermore, Ref. [

34] notes that the nature of the crisis dictates the stability of these growth relationships, a factor essential for understanding Romania’s performance during the financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the specific context of Romania, the literature reveals a remarkably stable adjustment process. Ref. [

35] emphasizes a highly statistically significant error correction term, which shows the long-run relationship and reflects the realistic institutional frictions inherent in the Romanian economy.

This stability is further explored by [

36], which confirms that productivity and export expansion are the primary transmission channels through which FDI impacts growth. Similarly, Ref. [

4] finds that these FDI effects remain robust even when accounting for other capital inflows, such as remittances. However, the Romanian evidence is mixed regarding the quality of growth. Ref. [

37] identifies an inverted-U relationship between FDI and income inequality, suggesting that initial growth may come at the cost of social dispersion before benefits diffuse. Additionally, while ref. [

38] argues for the existence of asymmetric effects and ref. [

39] points to a temporary weakening of linkages during the 2008 financial crisis, the broader consensus suggests a resilient structural relationship. This is reinforced by [

40], which argues that FDI stock in CEE is driven by long-term determinants like market size, exports or trade structure, rather than short-term cyclicality.

However, some authors question the positive relationship between the level of FDI inflow and the host country’s economic growth, arguing either that there is no interdependence between these economic variables [

41], or that the relationship is rather negative, at least in the short term. The impact of FDI on economic growth is not always positive, as it depends on the characteristics of the FDI, such as the type of investment, the sector of the host country’s economy where the FDI will be directed, the number of domestic enterprises in the sector, etc. [

42]. For example, the results of studies analyzing the effect of FDI on different sectors of the host economy have led to the conclusion that there can be significant differences in economic growth rates between various sectors, generated by FDI [

43].

The preceding review establishes the theoretical foundation for this study while highlighting several unresolved gaps in the Romanian context. We have built our study’s motivation and contribution directly upon these gaps, moving from a traditional GDP-centered analysis towards a more dynamic framework.

First, this study resolves the stock-flow ambiguity prevalent in the Romanian literature. While previous studies typically examine either FDI stock [

40] or flow [

36], we include both simultaneously in the model. Second, we extend the temporal coverage, capturing the full COVID-19 pandemic and the recovery cycle. Unlike earlier studies, this timeframe captures both the financial crisis and the pandemic. Third, from a methodological perspective, we shift the analysis from static models to a dynamic productivity growth specification. This approach reveals a temporal asymmetry as follows: while productivity improvements drive immediate short-run dynamics, FDI and exports operate exclusively as long-run structural anchors. Finally, this study integrates sustainability by relating our results to the broader paradigm of sustainable development.

3. Results

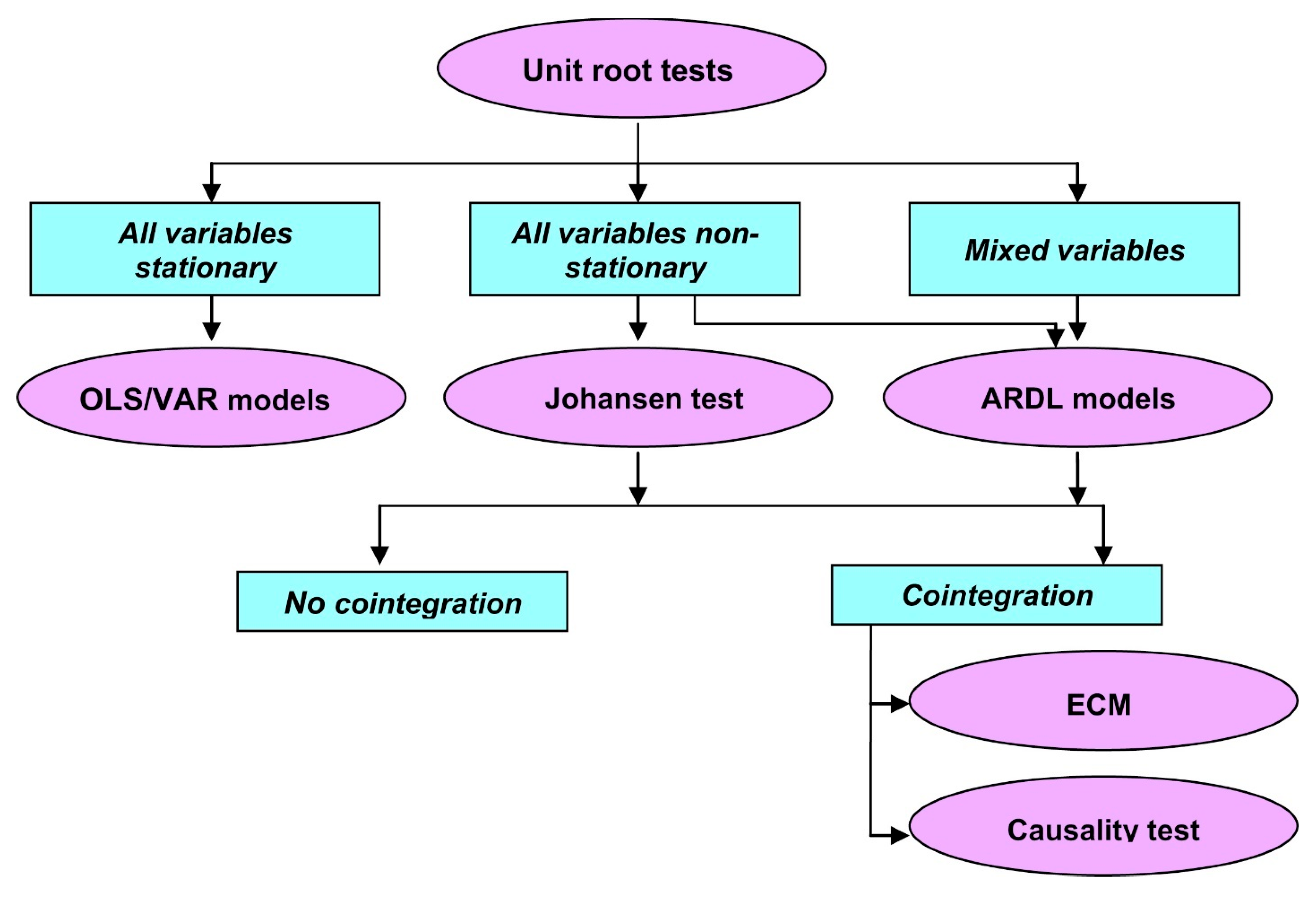

This section reports the empirical findings from our ARDL analysis, organized in five subsections as follows: stationarity test results, cointegration testing and model selection, long-run coefficient estimates, short-run dynamics through error correction model, and diagnostic tests confirming model validity.

The stationarity analysis of the time series under consideration is performed using EViews software, version 12. Thus, applying the ADF (augmented Dickey–Fuller) test, the following results are obtained, as exhibited in

Table 4 and

Table 5:

We selected the stationarity test type based on EViews results for the deterministic trend, checked through OLS regressions. To ensure the correct specification of the unit root tests (ADF and KPSS) and avoid potential biases, the choice between the “with constant” and “with constant & trend” specifications is determined by examining the statistical significance of the deterministic trend. Thus, at level, the trend coefficient proves to be statistically insignificant (p > 0.05) for ln(FDI) (p = 0.33) and GRLPEP (p = 0.21). Consequently, for the stationarity testing of these variables at level, the “with constant” specification is selected. In the case of the remaining variables, the trend coefficient is statistically significant (p < 0.05), leading to the adoption of the “with constant & trend”.

At the first difference, the trend coefficient is statistically insignificant for all variables; thus, the “with constant” specification is adopted.

To confirm the stationarity of the variables and their order of integration, we use the KPSS stationarity test. The results of this test are summarized in

Table 6.

As observed in

Table 5 and

Table 6, the ADF and KPSS stationarity tests yield contradictory results regarding the order of integration for several variables (e.g., lnRGDPC, lnFDI), discrepancies that are characteristic of small samples. However, this uncertainty confirms the mixed behavior of the variables and the fact that none exceed the I(1) order of integration. Given that the analyzed time series exhibit mixed orders of integration (strictly I(0) and I(1)), the ARDL (autoregressive distributed lag) model is selected for the econometric modeling, as it is specifically designed to handle such situations.

Before proceeding to the construction of an ARDL model, we check the correlation between the analyzed time series using the Pearson correlation coefficient (a value of +1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, –1 a perfect negative correlation, and 0 reflects no correlation). The Pearson correlation test, performed on the time series brought to stationarity, is conducted using SPSS software, version 27.

To avoid false correlations, the Pearson analysis requires strictly stationary series. Given the mixed results from the ADF and KPSS tests, we adopt a conservative approach as follows: first differences (Δ) are used for all variables where at least one test indicated non-stationarity or inconclusive results (i.e., lnRGDPC, lnFDI, lnFDIStock, lnEXP, and lnIMP). The variable GRLPEP is retained in its level form, as it is confirmed to be robustly stationary (I(0)) by both tests.

The results in

Table 7 highlight strong and statistically significant positive correlations between the real GDP per capita (ΔlnRGDPC) and the explanatory variables. Specifically, economic growth is most strongly correlated with GRLPEP (0.885), as well as with ΔlnFDI (0.674) and ΔlnFDIstock (0.563). On the other hand, the Pearson test reveals a very strong correlation between imports (ΔlnIMP) and exports ΔlnEXP (0.895), pointing to potential multicollinearity issues.

To confirm or refute these correlations in both the short and long run, we construct and interpret an ARDL econometric model and subsequently an ARDL-ECM model.

For the actual construction of the ARDL econometric model, we use EViews software. To generate such a model and test for cointegration, the first critical step is establishing the number of lags. These lags are chosen based on information criteria (AIC, BIC). We prioritized the Schwarz information criterion (BIC), as it imposes a stricter penalty for model complexity, making it better suited for shorter time series (N = 21) to avoid overfitting.

Determining the optimal lag length proves crucial for the model’s validity. Initially, a maximum lag order of two is tested to capture potential multi-year dynamic adjustments. However, the bounds test results for this specification (

Table 8) yield an F-statistic of 3.06, which falls below the I(1) critical value (3.79), indicating no cointegration. This result is attributed to the over-parameterization of the model relative to the small sample size, which consumes excessive degrees of freedom and reduces the power of the test.

Consequently, to strictly adhere to the principle of parsimony and ensure estimate stability, the maximum lag length was restricted to one. Under this refined specification, the results summarized in

Table 9 show a completely different picture. In this version, the F-statistic (15.35) significantly exceeds the critical value (3.79), strongly rejecting the null hypothesis. This confirms the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship and validates the construction of the ARDL-ECM model to analyze both short-term deviations and the speed of adjustment towards equilibrium.

Taking the coefficient values into account, the initial ARDL (1,0,0,1,1,1) long-run equation takes the following form:

According to this initial specification, the only variable showing a positive and significant long-term influence on economic growth (p < 0.10) is labor productivity (GRLPEP, p = 0.0919). The coefficients for FDI and exports appear statistically insignificant (p > 0.10). However, this lack of significance is likely a symptom of the high multicollinearity detected between imports and exports, which inflates standard errors and distorts the t-statistics.

The error correction model (ARDL-ECM) associated with this specification is:

According to this model, the most important variable that has a positive and significant short-term influence on economic growth at a significance level < 5% (p = 0.0002) is also GRLPEP.

The key element of the ARDL-ECM model is the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable, ln(RGDPCt−1). Its estimated value is −0.202274 and is statistically significant (p-value = 0.0269). The negative sign of this term confirms the model’s stability and the existence of an adjustment mechanism for the economy, moving from short-term economic shocks towards a long-run equilibrium state. In this model, the speed of adjustment, given by the magnitude of the adjustment coefficient (0.20227), indicates that approximately 20.2% of the disequilibrium (deviation from equilibrium) recorded in one year is corrected in the following year. This is a moderate speed of adjustment.

The results of this model must be viewed with caution, as two present variables (ln(IMP) and ln(EXP)) are strongly correlated; the Pearson correlation coefficient between the two variables is 0.895. In this situation, it is difficult for the model to isolate and accurately estimate the individual impact of each of the two variables on the dependent variable (economic growth).

To address this drawback, we eliminate one of the two variables from the model, namely the one that had the least influence on economic growth in the previous model (ln(IMP)). Following the removal of the (ln(IMP)) variable, Eviews will generate a new ARDL model (we keep the same specifications as in the previous ARDL model).

In the model refinement, despite the stability of the ECM, the results must be interpreted with caution. The diagnostic analysis reveals a strong Pearson correlation (0.895) between Δln(IMP) and Δln(EXP). As anticipated, this multicollinearity makes it difficult to isolate the individual impact of trade variables, rendering the FDI and export coefficients insignificant.

To address this drawback and improve the model’s robustness, we applied a “General-to-Specific” refinement procedure. The decision to eliminate imports (lnIMP) rather than exports (lnEXP) is based on two criteria. First, the statistical criterion is as follows: in the initial specification (

Table 10), the import variable exhibited a higher

p-value (

p = 0.4496) compared to exports (

p = 0.2545), indicating a lower level of statistical significance. Standard econometric practice dictates removing the least significant variable first to reduce multicollinearity. Second, the theoretical relevance criterion si as follows: within the context of the “export-led growth” hypothesis, exports are considered a more direct proxy for the positive spillovers of FDI (such as competitiveness and integration into global value chains) than imports.

Following the removal of the LN_IMP_ variable, EViews generated a refined ARDL model (keeping the same lag specifications), emphasized in

Table 11.

The refined model exhibits an F-statistic for the bounds test (23.73) significantly larger than that of the previous specification (15.35). Since the F-statistic (23.73) substantially exceeds the upper critical bound (I(1)) of 4.01 at the 5% significance level (and even the 1% level of 5.06, based on the critical values for k = 4 regressors provided by [

47], the null hypothesis of no levels relationship is strongly rejected.

Furthermore, the t-statistic associated with the lagged dependent variable (−4.56) falls well below the I(1) critical lower bound (−3.99) at the 5% level. The concordance of both tests confirms that the adjustment mechanism is functional, and that a stable, unidirectional long-run relationship exists, flowing from the explanatory variables to economic growth.

A. Long-Run Equilibrium Equation (Elasticities)

Based on the coefficients, the ARDL (1,0,0,0,1) long-run equilibrium equation takes the following form:

A crucial improvement over the initial model is observed here. While the previous specification yielded insignificant results for trade and investment variables, the refined model shows that all explanatory variables exert a positive and statistically significant influence on economic growth (p < 0.05). This validates the “general-to-specific” removal of the collinear import variable.

Specifically, the results highlight the dominant role of FDI stock in sustaining long-term economic performance. The elasticity coefficient of FDI stock (0.23) is statistically robust and nearly equivalent to that of exports (0.24).

This finding is critical for the paper’s central hypothesis. It demonstrates that the accumulated volume of foreign capital—representing permanent production capacities, technology transfer, and industrial modernization—is a fundamental pillar of Romania’s GDP per capita growth. Furthermore, the positive significance of FDI inflows (0.09) complements this finding, showing that while annual flows add incremental value, it is the consolidated stock of foreign investment that potentially has a significant impact on sustainable development.

B. Short-Run Dynamics (ARDL-ECM)

The short-run dynamics are captured by the conditional error correction regression (Equation 7), which was used to derive the bounds test statistics:

In the short run, the GDP dynamics is directly influenced by the growth rate of labor productivity (GRLPEP), the only regressor selected with a lag of one. Its significant coefficient indicates that productivity shocks have an immediate, instantaneous effect on economic growth.

Crucially, the specific behavior of FDI variables in the short-run model reinforces their structural importance. Unlike labor productivity, which acts as a short-term shock absorber (ΔGRLPEP), both FDI stock and FDI flows influence the growth rate through the long-run equilibrium mechanism (lag 0).

This implies that FDI does not merely generate volatile short-term fluctuations; instead, it plays a stabilizing, structural role. Foreign investments in Romania correct deviations from the equilibrium path, ensuring that the economy returns to its potential growth trajectory. This confirms that the impact of FDI is consistent and foundational, rather than speculative or transient.

The speed of adjustment, indicated by the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable (−0.279), is negative and highly significant (p = 0.0005). This indicates that approximately 27.9% of any disequilibrium caused by external shocks is corrected within one year. This adjustment speed is superior to the initial model (20.2%), suggesting that the refined specification better captures the economy’s reversion to its long-term growth path.

To validate the robustness of this final ARDL (1, 0, 0, 0, 1) model, a series of post-estimation diagnostic tests were conducted. The results confirmed the model’s quality:

Absence of autocorrelation: The Breusch–Godfrey LM (Lagrange multiplier) test indicates no serial correlation in the regression errors (residuals). Since F = 0.9355 > 0.05, the null hypothesis (H0: no serial autocorrelation of errors) is not rejected.

Homoscedasticity: The Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test, used to detect heteroscedasticity in the residuals, confirms the null hypothesis (H0: variance of errors is constant), as Prob. F = 0.4169 > 0.05.

Residual normality: The Jarque–Bera test shows that the residuals are normally distributed (H0: residuals are normally distributed is confirmed), as Prob. = 0.5914 > 0.05.

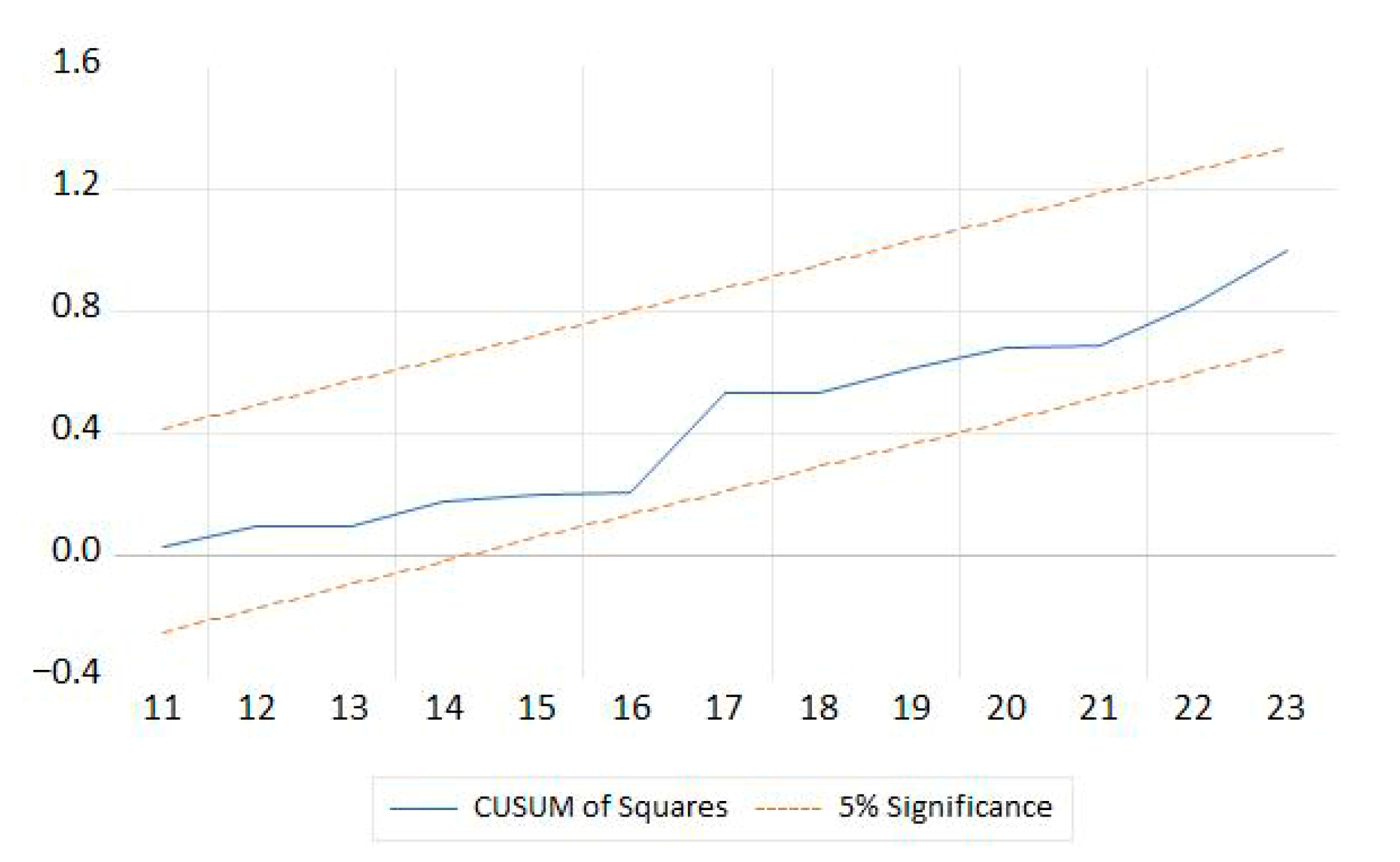

The CUSUM of squares test, used to detect sudden changes or instabilities in the error variance, confirms the null hypothesis that all coefficients are stable, with the test line remaining within the 5% confidence interval (

Figure 3). These results confirm structural stability across the EU ascension, global financial crisis, and COVID-19 pandemic.

These tests collectively demonstrate that the model is reliable and correctly specified, thus offering confidence in both the long-run and short-run estimations. The parameter stability finding is particularly important, indicating FDI–growth relationships remained structurally intact despite major shocks—providing confidence for policy recommendations based on stable long-run relationships.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study set out to answer whether foreign direct investment serves as a sustainable driver of economic growth in Romania, specifically by distinguishing between the impact of volatile annual flows and structural capital stock. The empirical analysis confirms a stable, positive long-run relationship between FDI and real GDP per capita. These findings are consistent with the broader pattern observed in Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies [

4,

39], where foreign capital has acted as a primary engine of convergence. However, unlike previous studies that focused heavily on inflows, our results clarify that accumulated stock and export capacity are the true vectors of sustainable growth, operating through long-term channels, while labor productivity acts as the essential short-term transmission mechanism. Also, parameter stability across periods of crisis confirms FDI–growth relationship remains structurally robust despite major shocks, providing confidence in FDI as a stable long-run development strategy.

Our results both confirm and extend previous research across multiple dimensions, positioning our study within the broader FDI-growth literature.

4.1. Long-Term Determinants of Economic Growth

In the long run, Romania’s economic growth is sustained by a synergistic mix of factors. Our findings align with the consensus in the literature regarding emerging European economies [

4,

39], confirming the positive and significant impact of foreign capital on economic growth. However, this study adds a critical nuance to the existing debate by distinguishing between the impact of annual flows and accumulated stock. While early studies often focused on the immediate effect of inflows [

41], our results validate the “capital accumulation” channel proposed by endogenous growth theories [

3]. Consequently, the final ARDL model provides robust evidence regarding the main drivers of development. First, regarding FDI stock as a structural pillar, the empirical analysis consistently highlights the fundamental role of accumulated foreign capital. Both the correlation analysis and the ARDL model estimation confirm that FDI stock is a significant driver of economic growth. This demonstrates that the consolidated volume of foreign investment, representing permanent production capacities and industrial modernization, has a structural impact nearly equivalent to that of exports. Second, regarding the FDI–export nexus, exports exhibited the highest elasticity, confirming the finding of [

24], which outlines that FDI and trade jointly promote growth. However, this result must be interpreted in the context of the strong multicollinearity detected between imports and exports, which necessitated the exclusion of imports to ensure model stability. Thus, the strong impact of exports indirectly amplifies the importance of attracting quality FDI that fosters export capacity. Third, regarding FDI flows, annual inflows have a positive but smaller contribution compared to the stock. This finding reinforces the conclusion that sustainable growth relies heavily on the retention and consolidation of capital (stock), rather than merely on volatile annual flows, a result that is consistent with [

36]. Fourth, regarding labor productivity, this remains a crucial internal factor, statistically significant in sustaining the long-term trend. This result is in line with the theoretical stance of [

19], which argued that FDI is more productive only when the host country possesses a sufficient level of absorptive capacity and human capital. Also, our results are consistent with [

36], who argue that FDI–growth nexus operates through productivity improvements and export competitiveness.

4.2. Short-Run Dynamics

The error correction modeling highlights a clear dichotomy in how factors influence GDP in the short term. Regarding immediate shocks, the growth rate of labor productivity acts as the primary immediate shock absorber. This underscores the rapidity with which efficiency gains translate into economic output. Conversely, regarding structural adjustment, FDI stock, FDI flows, and exports do not exhibit instantaneous volatility effects. Instead, they play a stabilizing role, influencing growth through the equilibrium restoration mechanism. Moreover, regarding the correction speed, the model indicates a robust adjustment speed of approximately 28% per year. This implies that the Romanian economy possesses a healthy capacity to correct disequilibria and return to its long-term potential trajectory following external shocks.

The diagnostic tests confirm the robustness of the model, which instills confidence in the interpretation of both the short-run and long-run effects.

Our study extends previous Romanian research in four ways. First, we include both FDI stock and FDI flow simultaneously in the model, enabling direct comparison of their relative growth effects, while previous studies use either FDI stock [

37,

40] or flow [

35,

36,

38]. Second, our sample period extends beyond existing studies on the relation between FDI and growth. Third, while [

36] includes productivity as the mediating channel, we use productivity growth rate rather than levels, capturing acceleration and momentum effects emphasized by the endogenous growth theory. Fourth, our detailed documentation of specification research ensures transparency and helps assess whether results are robust, also addressing robustness concerns.

4.3. Economic Policy Implications

The importance of this study lies in the fact that it is of interest to policymakers because it provides an evidence-based framework for transitioning from a volume-based growth model towards a strategy centered on sustainability. Rather than pursuing capital, the following recommendations offer a roadmap for channeling investment into sectors that align with European Green Deal and Romania’s long-term social objectives.

First, since one of the main results of this study emphasize that FDI–export nexus is significant to economic growth in Romania, we consider that this highlights the need for a fundamental shift in foreign investment, moving from generic attraction towards attracting quality FDI. By targeting FDI in high-tech sectors (e.g., renewable energy components, digital services), Romania can leverage the FDI-export channel to integrate into green global value chains, thereby reducing the carbon footprint of its exports.

Second, our finding that FDI stock is significantly more impactful than annual flows suggests that investor aftercare is more critical than attracting new investors. From an environmental perspective, updating the capital stock is essential for decarbonization. Long-term foreign investors are more likely to introduce cleaner production technologies that replace obsolete, energy-intensive assets. Therefore, fiscal incentives should prioritize the reinvestment of profits into green technologies, turning FDI stock into a catalyst for meeting the EU Green Deal targets.

Third, as in our study, labor productivity is the only significant short-run driver of growth, enhancing absorptive capacity which is essential for sustainability. To ensure FDI gains translate into higher wages rather than increased inequality, policy must prioritize human capital development. Furthermore, by using differential regional incentives to lead quality FDI into lower-developed regions, Romania can ensure that productivity growth fosters geographic cohesion and a more equitable distribution of wealth.

In conclusion, for emerging economies like Romania’s, the challenge is no longer merely attracting capital but channeling it effectively. A sustainable FDI strategy must focus on the quality of stock and the absorptive capacity of human capital, transforming foreign investment from a simple financial flow into a catalyst for the country’s sustainable convergence with developed EU economies.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study acknowledges several limitations inherent to the dataset and methodology, which contextualize the findings. The first limitation of our study is given by the sample size. The relatively short sample of twenty-one annual observations (2003–2023) restricts the degrees of freedom and prevents the inclusion of additional control variables without risking over-parameterization. Secondly, another limitation is the use of aggregate FDI data without a sectoral breakdown, which limits our ability to distinguish between the impact of high value-added investments (e.g., IT, automotive) and low-tech sectors. Consequently, the specific contribution of “green” vs. polluting industries could not be isolated econometrically. Thirdly, due to data constraints and multicollinearity concerns, the model omitted institutional quality indicators (e.g., corruption, rule of law) and specific sustainability indicators, such as carbon emissions or renewable energy adoption, which are relevant for a holistic sustainability analysis. The fourth limitation of our study refers to structural breaks as follows: while CUSUM tests confirmed stability, the sample size prevented the explicit modeling of structural breaks (e.g., the 2008 financial crisis) using dummy variables. Also, we could add a fifth limitation emphasized by the lack of inclusion in the analysis of environmental indicators (due to data unavailability reasons) or institutional quality indicators (due to limited time-series variations in annual data).

Future research should address these limitations by expanding the dataset to include quarterly observations or a longer time horizon, enabling a more granular econometric modeling. Additionally, sectoral decomposition of FDI (e.g., manufacturing, services, and green technologies) would provide deeper insights into the qualitative impact of foreign investments. Incorporating advanced econometric techniques such as nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) could capture asymmetric effects of FDI inflows and shocks. Furthermore, future research should address sectoral heterogeneity, firm-level spillovers, or structural breaks.

4.5. Concluding Remarks

This study examines the relationship between FDI and economic growth in Romania, during the 2003–2023 sample period, with a focus on distinguishing FDI stock and flow effects within a sustainable development framework. Our refined ARDL analysis, adjusted for multicollinearity, confirms stable long-run equilibrium relationships among FDI stock, FDI flow, exports, labor productivity growth, and GDP per capita. The policy implication is clear: retention and deepening of existing foreign presence should be prioritized over volume-based attraction of new investment.

The main contributions of our study are threefold. Methodologically, we provide a multicollinearity-adjusted ARDL model, transparent model selection documentation, and dynamic productivity specification innovation. Empirically, for Romania, our study is the first one that simultaneously includes FDI stock and FDI flow in the same model, extends the sample period to cover the COVID-19 pandemic and post-crisis recovery, and provides multi-crisis resilience evidence. As for policy recommendations, we provide evidence-based foundation for quality-over-quantity FDI strategies, sustainability-oriented policy guidance, and integrated export-FDI approaches.

Our findings confirm FDI can drive sustainable growth when combined with productivity enhancement and export competitiveness and quality-focused strategies. Romania’s challenge is translating accumulated FDI stock into deeper spillovers, broader diffusion, and more sustainable development, a challenge that requires not just attracting foreign capital, but strategically leveraging it for structural transformation aligned with 21st century imperatives of climate transition, digitalization, and social inclusion.