Deep Ensemble Learning Model for Waste Classification Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present efficient deep ensemble learning models, integrating pre-trained models with ensemble methods to provide more accurate results for waste management systems.

- We perform a comparative evaluation of the waste classification problem using sixteen different pre-trained DL models on four waste datasets.

- We provide a detailed overview of the existing studies on waste classification.

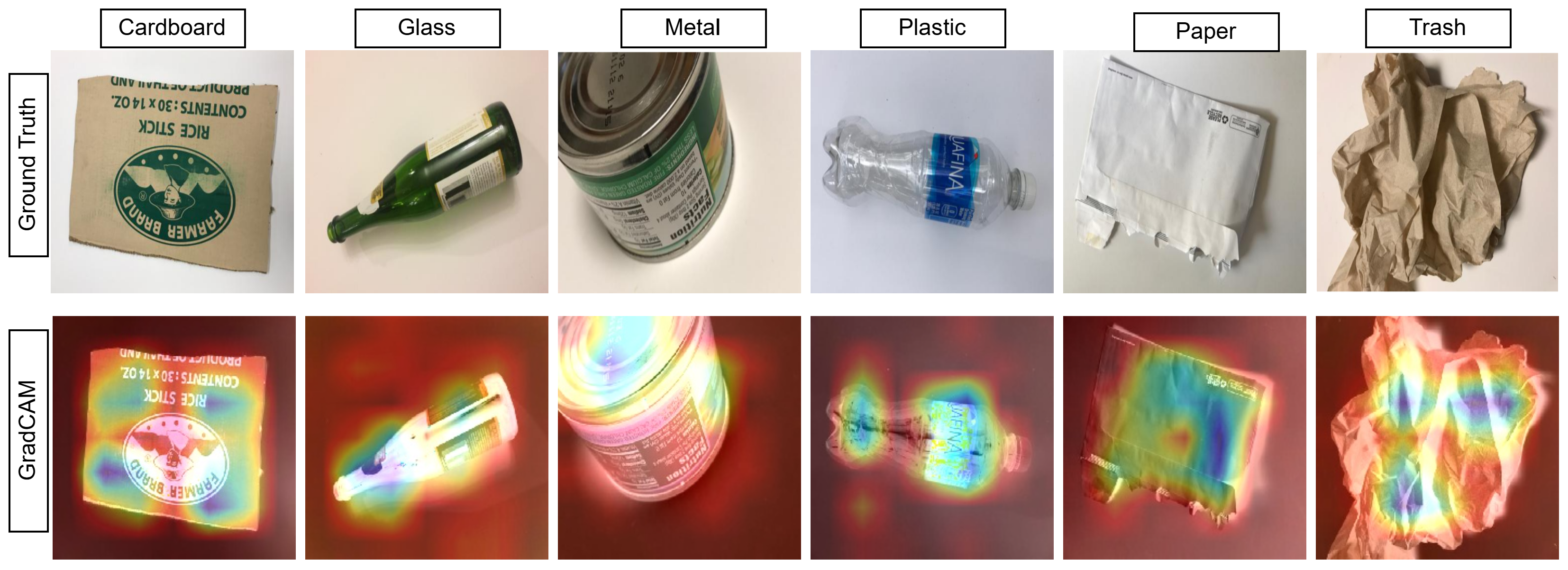

- We implement Grad-CAM method to ensure the explainability of models within the waste classification task.

2. Related Work

| Ref | Year | Task | ML/DL Model(s) | Dataset | #Class | Performance Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | 2016 | Waste classification | SIFT + SVM | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [25] | 2017 | Waste sorting | VGG-16 | Own data | 1 | Miss rate False rate |

| [26] | 2018 | Waste recognition | ResNet-34 | Own data | 6 | Accuracy |

| [27] | 2018 | Waste classification | CNN, MLP, AlexNet | Own data | 2 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall |

| [28] | 2018 | Waste classification | MobileNet | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [29] | 2018 | Waste classification | CNN, SVM, XGB, RF, KNN | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [21] | 2018 | Waste classification | ResNet50 | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [30] | 2019 | Waste detection, HSI classification | Multi-Scale CNN, | Indian Pines dataset, Pavia University dataset | 16 9 | Overall accuracy, Average accuracy, Kappa coefficient |

| [31] | 2019 | Waste classification | ResNet-50, SVM | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [41] | 2019 | Waste classification | VGG, Inception, ResNet | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [34] | 2020 | Waste classification | AutoEncoder, AlexNet, GoogLeNet, ResNet-50, SVM | Waste Classification data | 2 | Accuracy, Precision, F1-score |

| [33] | 2020 | Waste classification | VGG16, ResNet-50, Xception | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall |

| [35] | 2020 | Waste classification | Inception-v3 | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy |

| [42] | 2021 | Waste classification | InceptionV3 | Garbage Classification | 12 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F0.5-score |

| [36] | 2021 | Waste classification | MLH-CNN, VGG16, AlexNet, ResNet50 | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [37] | 2021 | Waste classification | ResNet18 | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [38] | 2022 | Waste detection Waste classification | EfficientDet-D2, EfficientNet-B2 | Detect-waste Cassify-waste | 8 | mAP, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [40] | 2022 | Waste classification | ResNeXt-50 | Medical waste dataset | 8 | Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [39] | 2022 | Waste detection Waste classification | ResNet-34, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, VGG-19, DenseNet-121 | TrashNet TACO TrashBox | 6 28 7 | Accuracy |

| [43] | 2023 | Waste classification | GoogleNet, ResNet, DenseNet, ResNeXt, EfficientNet | Garbage Classification | 12 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [44] | 2023 | Waste classification | VGGNet16, Resent50, MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, CNN | Garbage Classification | 8 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [45] | 2023 | Waste classification | ResNet18 | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [46] | 2023 | Waste detection Waste classification | MobileNet-v2 | HUAWEI-40 | 4 | Accuracy, Precision |

| [47] | 2023 | Waste classification | ResNet-34, ResNet-101, VGG-16 | TrashNet, TACO | 6 | Accuracy |

| [48] | 2024 | Waste classification | GoogleNet, ResNet50, Inception-v3, MobileNet-v2, DenseNet201. | TrashNet | 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, Specificity, F1-score |

| [49] | 2024 | Waste classification | VGG-16, ResNet-34, ResNet-50, AlexNet, LSTM | Recycle Waste image dataset | 2 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [50] | 2024 | Waste classification | VGG19 | TrashNet, GarClass | 6 6 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [51] | 2024 | Waste classification | YOLO 5, YOLO 7 | e-waste dataset | 5 | mAP, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

| [52] | 2024 | Waste classification | VGG16 | TrashNet, Own data | 6 | Accuracy |

| [53] | 2025 | Waste classification | CNN, YOLO | Own data | 4 | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score |

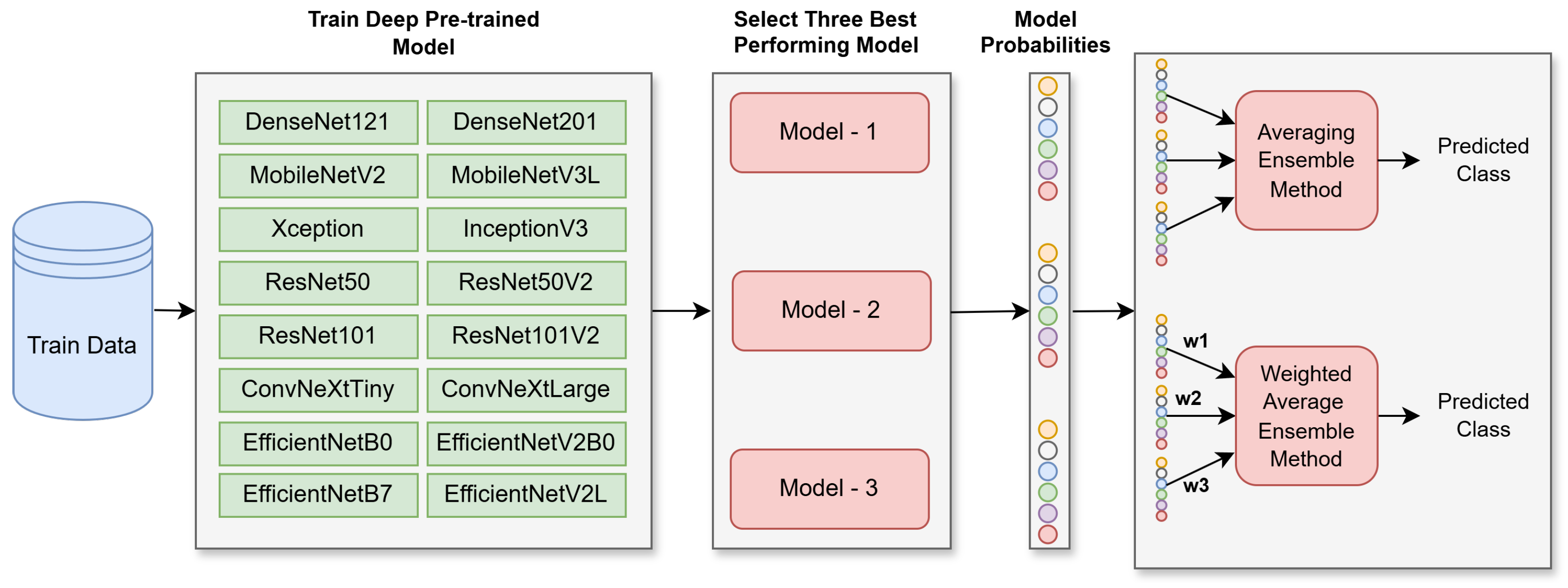

3. Proposed Deep Ensemble Model for Waste Classification

3.1. Pre-Trained Models

3.2. Ensemble Learning Methods

3.3. Proposed Deep Ensemble Model

| Algorithm 1 weighted averaging ensemble method |

|

4. Experimental Results and Evaluation

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. TrashNet

4.1.2. TrashBox

4.1.3. Waste Pictures

4.1.4. Garbage Classification

4.2. Performance Metrics

4.3. Experimental Results

4.4. Time Complexity Analysis

4.5. Discussion

4.6. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Macro Average | Weighted Average | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

| DenseNet121 | 90.5 | 88.1 | 91.9 | 89.4 | 91.2 | 90.5 | 90.6 |

| DenseNet201 | 87.4 | 86.3 | 86.7 | 86.2 | 88.1 | 87.4 | 87.4 |

| MobileNetV2 | 84.6 | 83.4 | 85.0 | 83.9 | 85.2 | 84.6 | 84.7 |

| MobileNetV3L | 89.3 | 87.1 | 89.9 | 88.2 | 89.8 | 89.3 | 89.4 |

| InceptionV3 | 83.4 | 80.9 | 80.4 | 80.5 | 83.7 | 83.4 | 83.4 |

| ResNet50 | 92.9 | 90.6 | 92.6 | 91.4 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 93.0 |

| ResNet50V2 | 83.0 | 81.0 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 83.6 | 83.0 | 83.2 |

| ResNet101 | 92.5 | 90.0 | 92.6 | 90.9 | 93.1 | 92.5 | 92.6 |

| ResNet101V2 | 87.0 | 85.2 | 87.7 | 85.7 | 88.2 | 87.0 | 87.0 |

| Xception | 83.8 | 81.2 | 84.4 | 81.9 | 85.3 | 83.8 | 84.1 |

| ConvNeXtTiny | 84.6 | 82.4 | 84.6 | 82.7 | 86.1 | 84.6 | 84.8 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 92.9 | 90.6 | 92.9 | 91.5 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 93.0 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 86.6 | 83.2 | 86.5 | 84.0 | 87.9 | 86.6 | 86.8 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 88.5 | 85.3 | 89.2 | 86.3 | 90.0 | 88.5 | 88.9 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 89.3 | 86.3 | 89.9 | 87.3 | 90.6 | 89.3 | 89.6 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 85.8 | 81.6 | 83.6 | 81.9 | 87.7 | 85.8 | 86.3 |

| Averaging ensemble | 94.9 | 93.0 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 95.0 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 96.0 | 94.0 | 97.0 | 95.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 |

| Macro Average | Weighted Average | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

| DenseNet121 | 83.7 | 83.5 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 84.0 | 83.7 | 83.7 |

| DenseNet201 | 85.1 | 85.1 | 85.3 | 84.9 | 85.8 | 85.1 | 85.2 |

| MobileNetV2 | 80.6 | 80.5 | 80.7 | 80.2 | 81.1 | 80.6 | 80.5 |

| MobileNetV3L | 85.8 | 85.7 | 85.7 | 85.6 | 85.9 | 85.8 | 85.7 |

| InceptionV3 | 79.6 | 79.7 | 79.7 | 79.3 | 80.3 | 79.6 | 79.6 |

| ResNet50 | 85.9 | 85.8 | 85.9 | 85.8 | 86.0 | 85.9 | 85.8 |

| ResNet50V2 | 82.4 | 82.8 | 82.0 | 82.3 | 82.7 | 82.4 | 82.4 |

| ResNet101 | 87.0 | 87.1 | 87.0 | 87.0 | 87.2 | 87.0 | 87.0 |

| ResNet101V2 | 84.9 | 84.8 | 84.8 | 84.7 | 84.9 | 84.9 | 84.8 |

| Xception | 82.1 | 82.3 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 82.5 | 82.1 | 82.2 |

| ConvNeXt | 87.2 | 87.1 | 87.2 | 87.1 | 87.3 | 87.2 | 87.2 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 94.9 | 95.0 | 94.8 | 94.9 | 94.9 | 94.9 | 94.9 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 87.3 | 87.1 | 87.4 | 87.2 | 87.4 | 87.3 | 87.3 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 87.1 | 87.0 | 87.2 | 87.0 | 87.3 | 87.1 | 87.1 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 88.3 | 88.0 | 88.3 | 88.1 | 88.4 | 88.3 | 88.3 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 87.5 | 87.3 | 87.5 | 87.4 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 87.5 |

| Averaging ensemble | 93.5 | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 95.8 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 |

| Macro Average | Weighted Average | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

| DenseNet121 | 89.8 | 90.6 | 87.6 | 88.6 | 90.1 | 89.8 | 89.6 |

| DenseNet201 | 90.3 | 90.8 | 88.9 | 89.5 | 90.6 | 90.3 | 90.3 |

| MobileNetV2 | 89.3 | 89.9 | 88.7 | 89.0 | 89.7 | 89.3 | 89.3 |

| MobileNetV3L | 91.1 | 91.3 | 89.8 | 90.4 | 91.2 | 91.1 | 91.0 |

| InceptionV3 | 86.5 | 87.3 | 84.8 | 85.6 | 87.0 | 86.5 | 86.5 |

| ResNet50 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 90.2 | 90.9 | 90.8 | 90.7 |

| ResNet50V2 | 89.7 | 90.8 | 88.4 | 89.2 | 90.2 | 89.7 | 89.7 |

| ResNet101 | 91.8 | 91.9 | 90.3 | 90.9 | 92.0 | 91.8 | 91.8 |

| ResNet101V2 | 88.0 | 87.8 | 86.7 | 86.9 | 88.5 | 88.0 | 87.9 |

| Xception | 87.8 | 88.4 | 85.5 | 86.5 | 88.1 | 87.8 | 87.7 |

| ConvNeXt | 90.5 | 91.1 | 89.1 | 89.8 | 90.8 | 90.5 | 90.5 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 97.2 | 97.4 | 96.9 | 97.1 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.2 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 91.4 | 91.1 | 90.2 | 90.5 | 91.5 | 91.4 | 91.3 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 93.8 | 93.9 | 93.5 | 93.6 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 93.8 | 93.9 | 93.1 | 93.3 | 93.9 | 93.8 | 93.7 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 90.4 | 90.9 | 89.4 | 90.0 | 90.5 | 90.4 | 90.4 |

| Averaging ensemble | 97.2 | 97.0 | 96.0 | 97.0 | 97.0 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Macro Average | Weighted Average | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

| DenseNet121 | 95.4 | 93.9 | 93.2 | 93.5 | 95.5 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| DenseNet201 | 96.3 | 94.9 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 96.5 | 96.3 | 96.3 |

| MobileNetV2 | 95.3 | 93.8 | 93.3 | 93.4 | 95.5 | 95.3 | 95.3 |

| MobileNetV3L | 95.6 | 94.2 | 93.7 | 93.9 | 95.7 | 95.6 | 95.6 |

| InceptionV3 | 93.0 | 90.1 | 89.5 | 89.7 | 93.1 | 93.0 | 93.0 |

| ResNet50 | 96.1 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.7 | 96.2 | 96.1 | 96.1 |

| ResNet50V2 | 94.1 | 91.0 | 90.8 | 90.7 | 94.2 | 94.1 | 94.1 |

| ResNet101 | 95.9 | 94.5 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 96.2 | 95.9 | 95.9 |

| ResNet101V2 | 94.8 | 92.3 | 92.4 | 92.3 | 94.9 | 94.8 | 94.8 |

| Xception | 94.5 | 92.1 | 91.7 | 91.7 | 94.7 | 94.5 | 94.5 |

| ConvNeXt | 96.8 | 95.6 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 96.9 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.6 | 98.9 | 98.8 | 98.8 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 95.9 | 94.6 | 94.0 | 94.3 | 95.9 | 95.9 | 95.9 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 96.3 | 95.0 | 94.9 | 94.9 | 96.4 | 96.3 | 96.3 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 97.6 | 96.5 | 96.6 | 96.5 | 97.7 | 97.6 | 97.6 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 96.5 | 95.4 | 95.1 | 95.2 | 96.6 | 96.5 | 96.5 |

| Averaging ensemble | 98.6 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 99.1 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 |

References

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z. An Automatic Garbage Classification System Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 140019–140029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.L.; He, J.; Xu, Z.; Huang, G. A combination model based on transfer learning for waste classification. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, K.; Zou, H.; Xie, L. GarbageNet: A Unified Learning Framework for Robust Garbage Classification. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoya, S.A.; Oyinlola, M.; Schröder, P.; Kolade, O.; Abolfathi, S. Enhancing decentralised recycling solutions with digital technologies. In Digital Innovations for a Circular Plastic Economy in Africa; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023; Volume 208. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; Pereira, F., Burges, C., Bottou, L., Weinberger, K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going Deeper with Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; PMLR: Cambridge MA, USA, 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollar, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26, July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge MA, USA, 2019; Volume 97, pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Pacal, I.; Kilicarslan, S.; Ozdemir, B.; Deveci, M.; Kadry, S. Efficient and autonomous detection of olive leaf diseases using AI-enhanced MetaFormer. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacal, I.; Akhan, O.; Deveci, R.T.; Deveci, M. NeXtBrain: Combining local and global feature learning for brain tumor classification. Brain Res. 2025, 1863, 149762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacal, I.; Attallah, O. InceptionNeXt-Transformer: A novel multi-scale deep feature learning architecture for multimodal breast cancer diagnosis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 110, 108116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacal, I.; Attallah, O. Hybrid deep learning model for automated colorectal cancer detection using local and global feature extraction. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 319, 113625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S.; Alizadehsani, R.; Nahavandi, D.; Mohamed, S.; Mohajer, N.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Hossain, I. A comprehensive review on autonomous navigation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, S.; Mazzia, V.; Salvetti, F.; Martini, M.; Angarano, S.; Navone, A.; Chiaberge, M. A deep learning driven algorithmic pipeline for autonomous navigation in row-based crops. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 138306–138318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, G.E.; Mokbel, M.; Darwich, A.; Khneisser, M.N.; Hadi, A. Comparing deep learning and support vector machines for autonomous waste sorting. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Multidisciplinary Conference on Engineering Technology (IMCET), Beirut, Lebanon, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Thung, G. Classification of Trash for Recyclability Status; Technical Report; CS229 Project Report; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bircanoğlu, C.; Atay, M.; Beşer, F.; Genc, O.; Kızrak, M.A. RecycleNet: Intelligent Waste Sorting Using Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications (INISTA), Thessaloniki, Greece, 3–5 July 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y. PublicGarbageNet: A Deep Learning Framework for Public Garbage Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 7200–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Jiao, H. Garbage classification system based on improved ShuffleNet v2. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi, O.; Rokach, L. Ensemble learning: A survey. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2018, 8, e1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhihong, C.; Hebin, Z.; Yanbo, W.; Binyan, L.; Yu, L. A vision-based robotic grasping system using deep learning for garbage sorting. In Proceedings of the 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Dalian, China, 26–28 July 2017; pp. 11223–11226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lian, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Liu, D. Deep Learning Based Robot for Automatically Picking Up Garbage on the Grass. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2018, 64, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Huang, C.; Xie, X.; Tan, B.; Kamal, S.; Xiong, X. Multilayer Hybrid Deep-Learning Method for Waste Classification and Recycling. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018, 2018, 5060857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabano, S.L.; Cabatuan, M.K.; Sybingco, E.; Dadios, E.P.; Calilung, E.J. Common Garbage Classification Using MobileNet. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Baguio City, Philippines, 29 November–2 December 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satvilkar, M. Image Based Trash Classification Using Machine Learning Algorithms for Recyclability Status. Master’s Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y. Multi-Scale CNN Based Garbage Detection of Airborne Hyperspectral Data. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 104514–104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, O.; Wang, Z. Intelligent Waste Classification System Using Deep Learning Convolutional Neural Network. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, V.; Sánchez, Á.; Vélez, J.F.; Raducanu, B. Automatic Image-Based Waste Classification. In Proceedings of the From Bioinspired Systems and Biomedical Applications to Machine Learning, Almería, Spain, 3–7 June 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 422–431. [Google Scholar]

- Rismiyati; Endah, S.N.; Khadijah; Shiddiq, I.N. Xception Architecture Transfer Learning for Garbage Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences (ICICoS), Semarang, Indonesia, 10–11 November 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toğaçar, M.; Ergen, B.; Cömert, Z. Waste classification using AutoEncoder network with integrated feature selection method in convolutional neural network models. Measurement 2020, 153, 107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, F.A.; Suhaimi, H.; Abas, E. Waste Classification using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Communications, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–14 August 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tan, C.; Wang, T.; Wang, L. A Waste Classification Method Based on a Multilayer Hybrid Convolution Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Mu, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Recyclable waste image recognition based on deep learning. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 171, 105636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrowska, S.; Mikołajczyk, A.; Ferlin, M.; Klawikowska, Z.; Plantykow, M.A.; Kwasigroch, A.; Majek, K. Deep learning-based waste detection in natural and urban environments. Waste Manag. 2022, 138, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumsetty, N.V.; Bhat Nekkare, A.; Sowmya, S.K.; Kumar, A.M. TrashBox: Trash Detection and Classification using Quantum Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 31st Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), Helsinki, Finland, 27–29 April 2022; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, X.; Alhaskawi, A.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Q.; Hu, X.; Liu, Z.; Kota, V.G.; Abdulla, M.H.A.H.; et al. A deep learning approach for medical waste classification. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Pictures. 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/wangziang/waste-pictures (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Jin, J.; Wang, H.; Xing, Q.; Zhang, Y. Clean Our City: An Automatic Urban Garbage Classification Algorithm Using Computer Vision and Transfer Learning Technologies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1994, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukurov, R. Garbage classification based on fine-tuned state-of-the-art models. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Rome, Italy, 3–6 July 2023; pp. 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Shama, U.S.; Akash, M.; Karim, D.Z. Automatic Waste Classification System using Deep Leaning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 19–21 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, M.; Xu, T.; Dong, S.Q. A waste classification method based on a capsule network. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 86454–86462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Yang, Z.; Królczykg, G.; Liu, X.; Gardoni, P.; Li, Z. Garbage detection and classification using a new deep learning-based machine vision system as a tool for sustainable waste recycling. Waste Manag. 2023, 162, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumsetty, N.V.; Nekkare, A.B.; Sowmya Kamath, S.; Anand Kumar, M. An Approach for Waste Classification Using Data Augmentation and Transfer Learning Models. In Machine Vision and Augmented Intelligence: Select Proceedings of MAI 2022; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Majid, M.E.; Kashem, S.B.A.; Khandakar, A.; Nashbat, M.; Ashraf, A.; Hasan-Zia, M.; Kunju, A.K.A.; Kabir, S.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. A Reliable and Robust Deep Learning Model for Effective Recyclable Waste Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 13809–13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilhore, U.K.; Simaiya, S.; Dalal, S.; Damaševičius, R. A smart waste classification model using hybrid CNN-LSTM with transfer learning for sustainable environment. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 29505–29529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, M.K.; Nguyen, D.C.; Nguyen, V.D.; Wijayasundara, M.; Setunge, S.; Pathirana, P.N. Toward Privacy-Preserving Waste Classification in the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 24814–24830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarswat, P.K.; Singh, R.S.; Pathapati, S.V.S.H. Real time electronic-waste classification algorithms using the computer vision based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): Enhanced environmental incentives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 207, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhou, M.; Wang, B.; Qin, H. Waste classification strategy based on multi-scale feature fusion for intelligent waste recycling in office buildings. Waste Manag. 2024, 190, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.K.; Ali, Y.; Kumar, R.R.; Assaf, M.H.; Ilyas, S. Artificial Intelligent and Internet of Things framework for sustainable hazardous waste management in hospitals. Waste Manag. 2025, 203, 114816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.; Daneshkhah, A.; Abolfathi, S. Forecasting global climate drivers using Gaussian processes and convolutional autoencoders. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.; Islam, M.S. A new ensemble learning approach to detect malaria from microscopic red blood cell images. Sensors Int. 2023, 4, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, R.; Arora, S. A hybrid evolutionary weighted ensemble of deep transfer learning models for retinal vessel segmentation and diabetic retinopathy detection. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 115, 109107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Ahn, J.; Lee, K. Opinion mining using ensemble text hidden Markov models for text classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 94, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, S.; Hu, J.; Ni, W.; Liu, J. TextCNN-based ensemble learning model for Japanese Text Multi-classification. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 109, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, B. An intrusion detection system based on stacked ensemble learning for IoT network. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 110, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jethanandani, M.; Sharma, A.; Perumal, T.; Chang, J.R. Multi-label classification based ensemble learning for human activity recognition in smart home. Internet Things 2020, 12, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, G.; Yang, M. Trashnet. 2016. Available online: https://github.com/garythung/trashnet (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Garbage Classification. 2021. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mostafaabla/garbage-classification (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Attallah, O.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Zakzouk, N.E. A lightweight deep learning framework for transformer fault diagnosis in smart grids using multiple scale CNN features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Liang, R.; Song, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, J.; Yan, B.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, G. Noise-assisted data enhancement promoting image classification of municipal solid waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 209, 107790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Year | Parameter | Depth | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InceptionV3 | 2015 | 23.9 M | Deep | Complex |

| ResNet50 | 2015 | 25.6 M | Deep | Moderate |

| ResNet50V2 | 2016 | 25.6 M | Deep | Moderate |

| ResNet101 | 2015 | 44.7 M | Deep | Complex |

| ResNet101V2 | 2016 | 44.7 M | Deep | Complex |

| DenseNet121 | 2016 | 8.1 M | Deep | Complex |

| DenseNet201 | 2017 | 20.2 M | Deep | Complex |

| Xception | 2017 | 22.9 M | Deep | Complex |

| MobileNetV2 | 2018 | 3.5 M | Shallow | Lightweight |

| MobileNetV3L | 2019 | 3.9 M | Shallow | Lightweight |

| EfficientNetB0 | 2019 | 5.3 M | Moderate | Efficient |

| EfficientNetB7 | 2019 | 66.7 M | Moderate | Efficient |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 2021 | 7.2 M | Moderate | Efficient |

| EfficientNetV2L | 2021 | 119.0 M | Moderate | Efficient |

| ConvNeXtTiny | 2022 | 28.6 M | Moderate | Complex |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 2022 | 197.7 M | Moderate | Complex |

| Dataset | # Images | # Classes | Class Imbalance | Type | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrashNet | 2527 | 6 | Low | Classification | Clear background |

| TrashBox | 17,853 | 7 | Low | Classification | Scraped from web |

| Garbage Classification | 15,515 | 12 | High | Classification | Scraped from web |

| Waste Pictures | 23,087 | 34 | High | Classification | Scraped from Google search |

| Dataset | Train | Validation | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrashNet | 2021 | 253 | 253 | 2527 |

| TrashBox | 14,279 | 1781 | 1793 | 17,853 |

| Waste Pictures | 14,268 | 3567 | 5252 | 23,087 |

| Garbage Classification | 12,412 | 1551 | 1552 | 15,515 |

| Dataset | Train | Validation | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrashNet | 3564 | 253 | 253 | 4070 |

| TrashBox | 16,835 | 1781 | 1793 | 20,409 |

| Waste Pictures | 14,268 | 3567 | 5252 | 23,087 |

| Garbage Classification | 12,412 | 1551 | 1552 | 15,515 |

| Dataset | TrashNet | TrashBox | Waste Pictures | Garbage Classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Loss | Accuracy | Loss | Accuracy | Loss | Accuracy | Loss | Accuracy |

| DenseNet121 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.95 |

| DenseNet201 | 0.32 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 0.85 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.12 | 0.96 |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.45 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.89 | 0.17 | 0.95 |

| MobileNetV3L | 0.34 | 0.89 | 0.45 | 0.86 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 0.96 |

| InceptionV3 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.87 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| ResNet50 | 0.27 | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.96 |

| ResNet50V2 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.35 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.94 |

| ResNet101 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.45 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.13 | 0.96 |

| ResNet101V2 | 0.44 | 0.87 | 0.52 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.95 |

| Xception | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.82 | 0.40 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.94 |

| ConvNeXtTiny | 0.44 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 0.97 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.99 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 0.33 | 0.89 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 0.94 | 0.12 | 0.96 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.13 | 0.96 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 0.35 | 0.89 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.22 | 0.94 | 0.11 | 0.98 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 0.39 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.97 |

| Model | Optimizer | LR | # Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| DenseNet121 | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 7,044,679 |

| DenseNet201 | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 18,335,431 |

| MobileNetV2 | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 2,266,951 |

| MobileNetV3L | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 3,003,079 |

| InceptionV3 | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 21,817,127 |

| ResNet50 | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 23,602,055 |

| ResNet50V2 | SGD | 1 × 10−2 | 23,579,143 |

| ResNet101 | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 42,672,519 |

| ResNet101V2 | SGD | 1 × 10−2 | 42,640,903 |

| Xception | RMSprop | 1 × 10−3 | 20,875,823 |

| ConvNeXtTiny | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 27,825,511 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 196,241,095 |

| EfficientNetB0 | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 4,058,538 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 5,928,279 |

| EfficientNetV2L | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 117,755,815 |

| EfficientNetB7 | Adam | 1 × 10−3 | 64,115,614 |

| Models | Averaging Ensemble (%) | Weighted Average Ensemble (%) | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|

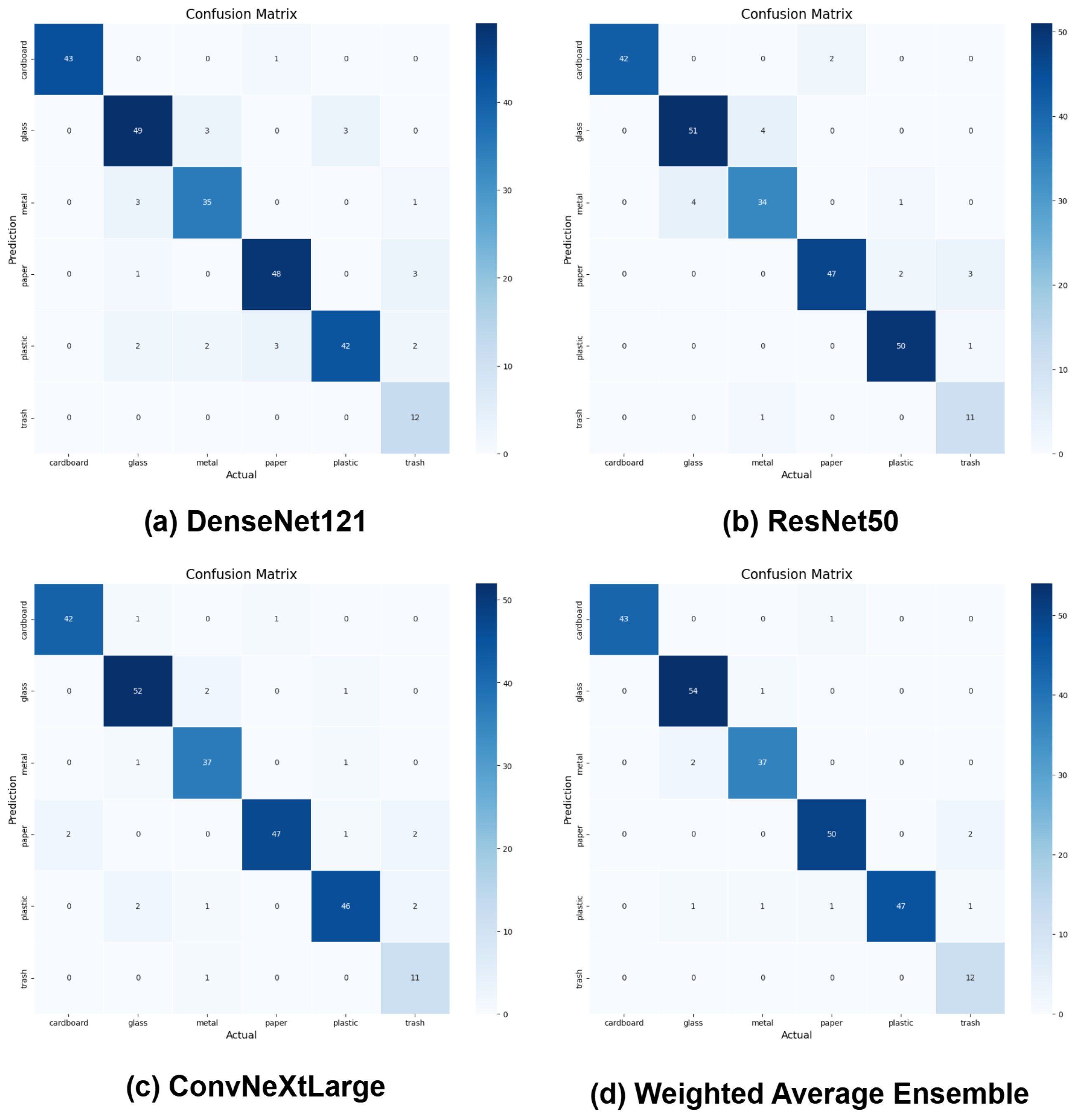

| DenseNet121, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 94.9 | 96.0 | 0.33, 0.22, 0.44 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.7 | 96.0 | 0.35, 0.18, 0.47 |

| ResNet50, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 94.9 | 95.3 | 0.17, 0.33, 0.5 |

| DenseNet121, MobileNetV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 94.1 | 95.3 | 0.17, 0.33, 0.5 |

| ResNet50, MobileNetV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 94.1 | 95.3 | 0.34, 0.06, 0.6 |

| ResNet101, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.3 | 94.5 | 0.25, 0.25, 0.5 |

| EfficientNetB7, Xception, ConvNeXtLarge | 91.3 | 94.1 | 0.17, 0.16, 0.67 |

| ResNet50, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtTiny | 91.7 | 94.1 | 0.62, 0.31, 0.07 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DenseNet121 | 90.5 | 88.1 | 91.9 | 89.4 |

| ResNet50 | 92.9 | 90.6 | 92.6 | 91.4 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 92.9 | 90.6 | 92.9 | 91.5 |

| Averaging ensemble | 94.9 | 93.0 | 94.0 | 94.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 96.0 | 94.0 | 97.0 | 95.0 |

| Models | Averaging Ensemble (%) | Weighted Average Ensemble (%) | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.5 | 95.8 | 0.07, 0.33, 0.6 |

| ResNet101, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtLarge | 94.1 | 95.6 | 0.33, 0.09, 0.58 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.8 | 95.6 | 0.09, 0.33, 0.58 |

| DenseNet121, MobileNetV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.4 | 95.5 | 0.1, 0.2, 0.7 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.0 | 95.4 | 0.18, 0.18, 0.64 |

| EfficientNetB7, Xception, ConvNeXtLarge | 93.9 | 95.3 | 0.22, 0.22, 0.56 |

| ResNet50, EfficientNetV2B0, ConvNeXtTiny | 91.5 | 91.9 | 0.3, 0.35, 0.35 |

| DenseNet121, DenseNet201, EfficientNetB0 | 88.6 | 89.7 | 0.11, 0.33, 0.56 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50 | 85.9 | 85.8 | 85.9 | 85.8 |

| ResNet101 | 87.0 | 87.1 | 87.0 | 87.0 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 94.9 | 95.0 | 94.8 | 94.9 |

| Averaging ensemble | 93.5 | 93.0 | 93.0 | 93.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 95.8 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 |

| Models | Averaging Ensemble (%) | Weighted Average Ensemble (%) | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtLarge | 97.2 | 98.0 | 0.22, 0.22, 0.56 |

| ResNet101, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtLarge | 96.8 | 98.0 | 0.19, 0.25, 0.56 |

| EfficientNetB0, EfficientNetV2B0, ConvNeXtLarge | 97.3 | 97.9 | 0.25, 0.19, 0.56 |

| EfficientNetV2B0, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 97.0 | 97.9 | 0.27, 0.18, 0.54 |

| EfficientNetB0, InceptionV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 97.0 | 97.9 | 0.31, 0.07, 0.62 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 96.0 | 97.8 | 0.1, 0.2, 0.7 |

| ResNet50, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 96.1 | 97.7 | 0.15, 0.23, 0.62 |

| ResNet101V2, InceptionV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 95.5 | 97.7 | 0.13, 0.12, 0.75 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 90.2 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 97.2 | 97.4 | 96.9 | 97.1 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 93.8 | 93.9 | 93.5 | 93.6 |

| Averaging ensemble | 97.2 | 97.0 | 96.0 | 97.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Models | Averaging Ensemble (%) | Weighted Average Ensemble (%) | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|

| EfficientNetB7, Xception, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.6 | 99.1 | 0.2, 0.2, 0.6 |

| DenseNet121, MobileNetV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.0 | 99.0 | 0.06, 0.41, 0.53 |

| ResNet50, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.1 | 99.0 | 0.08, 0.25, 0.67 |

| ResNet101, EfficientNetB0, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.3 | 99.0 | 0.25, 0.25, 0.5 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet101, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.1 | 99.0 | 0.14, 0.14, 0.72 |

| DenseNet121, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 97.9 | 98.9 | 0.14, 0.14, 0.72 |

| ResNet50, MobileNetV3, ConvNeXtLarge | 98.3 | 98.9 | 0.2, 0.2, 0.6 |

| ResNet50, EfficientNetV2B0, ConvNeXtTiny | 97.6 | 97.7 | 0.1, 0.8, 0.1 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xception | 94.5 | 92.1 | 91.7 | 91.7 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.6 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 95.9 | 94.6 | 94.0 | 94.3 |

| Averaging ensemble | 98.6 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| Weighted average ensemble | 99.1 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 99.0 |

| Model | Accuracy p-Value | F1-Score p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| DenseNet121 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| ResNet50 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| MobileNetV3Large | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Dataset | TrashNet | TrashBox | Waste Pictures | Garbage Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Training Time(s) | |||

| DenseNet121 | 770 | 3596 | 2842 | 2173 |

| DenseNet201 | 674 | 3615 | 1254 | 2063 |

| MobileNetV2 | 515 | 3582 | 1916 | 1997 |

| MobileNetV3L | 1001 | 4685 | 2377 | 1400 |

| InceptionV3 | 746 | 3902 | 2165 | 2607 |

| ResNet50 | 688 | 4600 | 1648 | 3408 |

| ResNet50V2 | 737 | 4245 | 2122 | 1685 |

| ResNet101 | 624 | 4585 | 2121 | 1399 |

| ResNet101V2 | 842 | 3527 | 1670 | 1401 |

| Xception | 596 | 3556 | 2385 | 1702 |

| ConvNeXtTiny | 1034 | 5356 | 2840 | 3821 |

| ConvNeXtLarge | 429 | 4672 | 1483 | 2667 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 497 | 2864 | 2845 | 1869 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 1066 | 8689 | 1809 | 2585 |

| EfficientNetV2B0 | 858 | 6033 | 3066 | 1860 |

| EfficientNetV2L | 882 | 7956 | 3750 | 3405 |

| Proposed Method | 1887 | 13,856 | 5975 | 6953 |

| Reference | Method | Train / Val / Test Ratio (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Yang et al., 2016) [20] | SIFT + SVM | 70/13/17 | 63 |

| (Kumsetty et al., 2022) [39] | Quantum ResNet-50 | Not specified | 80.5 |

| (Bircanoğlu et al., 2018) [21] | RecycleNet | 70/13/17 | 81 |

| (Adedeji et al., 2019) [31] | ResNet-50 + SVM | Not specified | 87 |

| (Rabano et al., 2018) [28] | MobileNet | Not specified | 87.2 |

| (Endah et al., 2020) [33] | Xception | 80/20 | 88 |

| (Ruiz et al., 2019) [32] | Inception-ResNet | 80/10/10 | 88.6 |

| (Satvilkar et al., 2018) [29] | CNN | 75/25 | 89.8 |

| (Quan et al., 2024) [50] | VGG19 | 80/20 | 90.0 |

| (Huang et al., 2023) [45] | ResNet18 | 80/20 | 91.4 |

| (Azis et al., 2020) [35] | Inception-v3 | 80/10/10 | 92.5 |

| (Shi et al., 2021) [36] | MLH-CNN, | 80/20 | 92.6 |

| (Kumsetty et al., 2023) [47] | ResNet-34 | 80/10/10 | 93.1 |

| (Lin et al., 2024) [52] | VGG16 | 80/20 | 94.1 |

| (Hossen et al., 2024) [48] | DenseNet201,MobileNet-v2 | 70/20/10 | 95.0 |

| Proposed model (average ensemble) | DenseNet121, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 80/10/10 | 94.9 |

| Proposed model (weighted average ensemble) | DenseNet121, ResNet50, ConvNeXtLarge | 80/10/10 | 96.0 |

| Reference | Method | #Class | Train/Val/Test Ratio (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Chen et al., 2021) [42] | InceptionV3 | 12 | 80/10/10 | 93.1 |

| (Shukurov, 2023) [43] | ResNeXt | 12 | 80/10/10 | 95 |

| (Dey et al., 2023) [44] | custom CNN | 8 | 80/20 | 97.58 |

| Proposed model (average ensemble) | EfficientNetB7, Xception, ConvNeXtLarge | 12 | 80/10/10 | 98.6 |

| Proposed model (weighted average ensemble) | EfficientNetB7, Xception, ConvNeXtLarge | 12 | 80/10/10 | 99.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alkılınç, A.; Okay, F.Y.; Kök, İ.; Özdemir, S. Deep Ensemble Learning Model for Waste Classification Systems. Sustainability 2026, 18, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010024

Alkılınç A, Okay FY, Kök İ, Özdemir S. Deep Ensemble Learning Model for Waste Classification Systems. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkılınç, Ahmet, Feyza Yıldırım Okay, İbrahim Kök, and Suat Özdemir. 2026. "Deep Ensemble Learning Model for Waste Classification Systems" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010024

APA StyleAlkılınç, A., Okay, F. Y., Kök, İ., & Özdemir, S. (2026). Deep Ensemble Learning Model for Waste Classification Systems. Sustainability, 18(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010024