Investigation of the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Wandering Reach with Multiple Mid-Channel Shoals in the Upper Yellow River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Measurement Methods and Result Analysis

2.1. Instrumentation

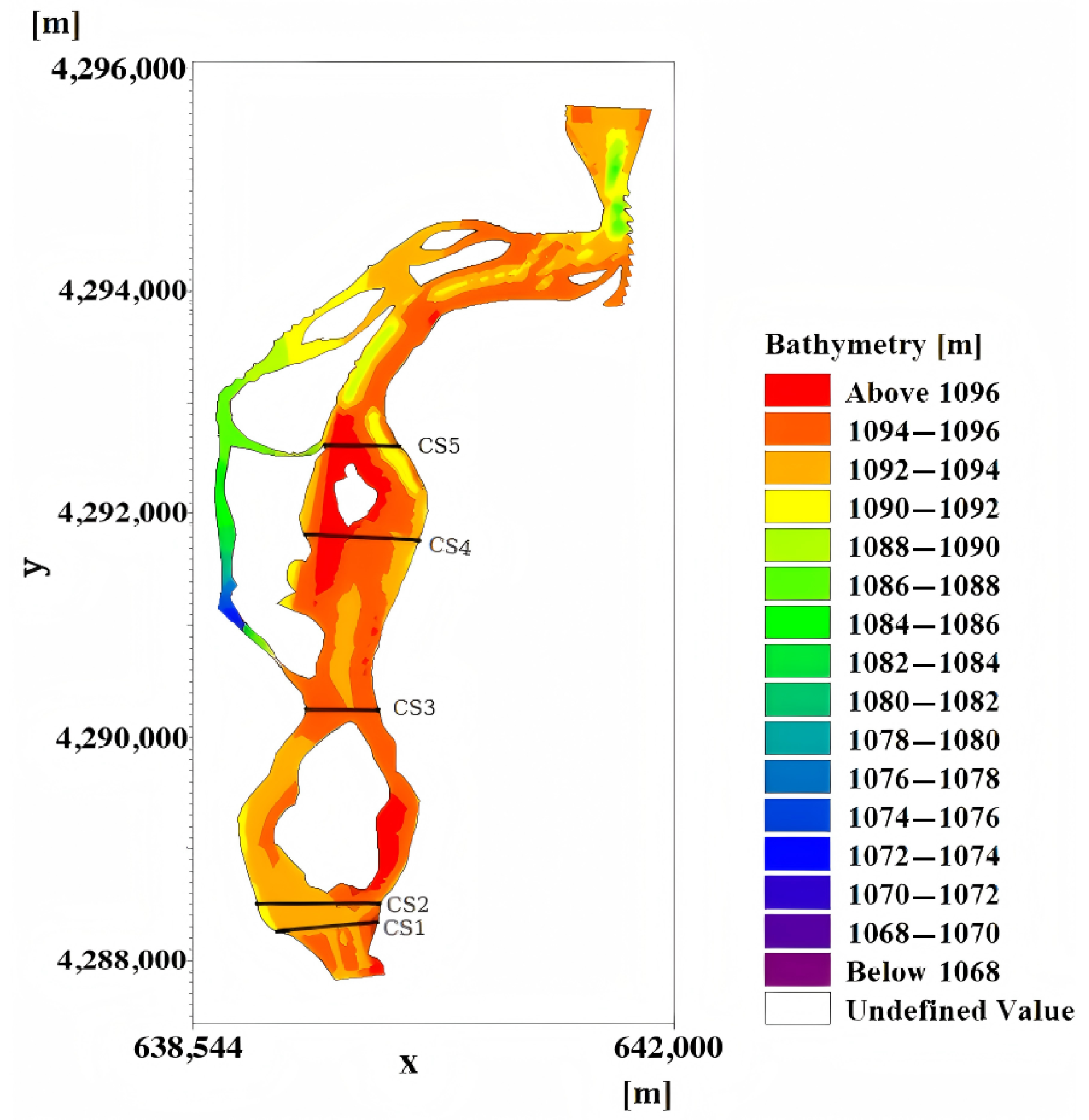

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Measurement Methods

2.4. Measurement Results and Analysis

3. Two-Dimensional Numerical Simulation of Meandering Channel with Mid-Channel Shoals and Spur Dikes

3.1. Governing Equations

3.2. Numerical Method

3.3. Model Validation

3.4. Uncertainty Analysis

4. Analysis of Numerical Results

4.1. Full-Field Velocity Analysis

4.2. Global Flow Field Analysis

4.3. Local Flow Field Analysis

4.4. Head Loss Analysis

4.5. Analysis of Bed Deformation Simulation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Measured Flow Bifurcation Mechanism and Velocity Probability Distribution Characteristics at Mid-Channel Shoal

5.2. Head Loss Characteristics

5.3. Numerical Simulation of Discharge Effects on Bed Erosion–Deposition Patterns

5.4. Complex Flow–Sediment Interaction Mechanisms in Coupled Bend-Shoal Systems

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Mid-channel shoals geometry together with bend-induced planform effects controls the depth-averaged flow partitioning. The right-branch discharge ratio is 44.16% at Z01 and 86.31% at Z02. At Z02, the S-shaped successive-bend setting promotes depth-averaged flow deflection toward the right branch.

- (2)

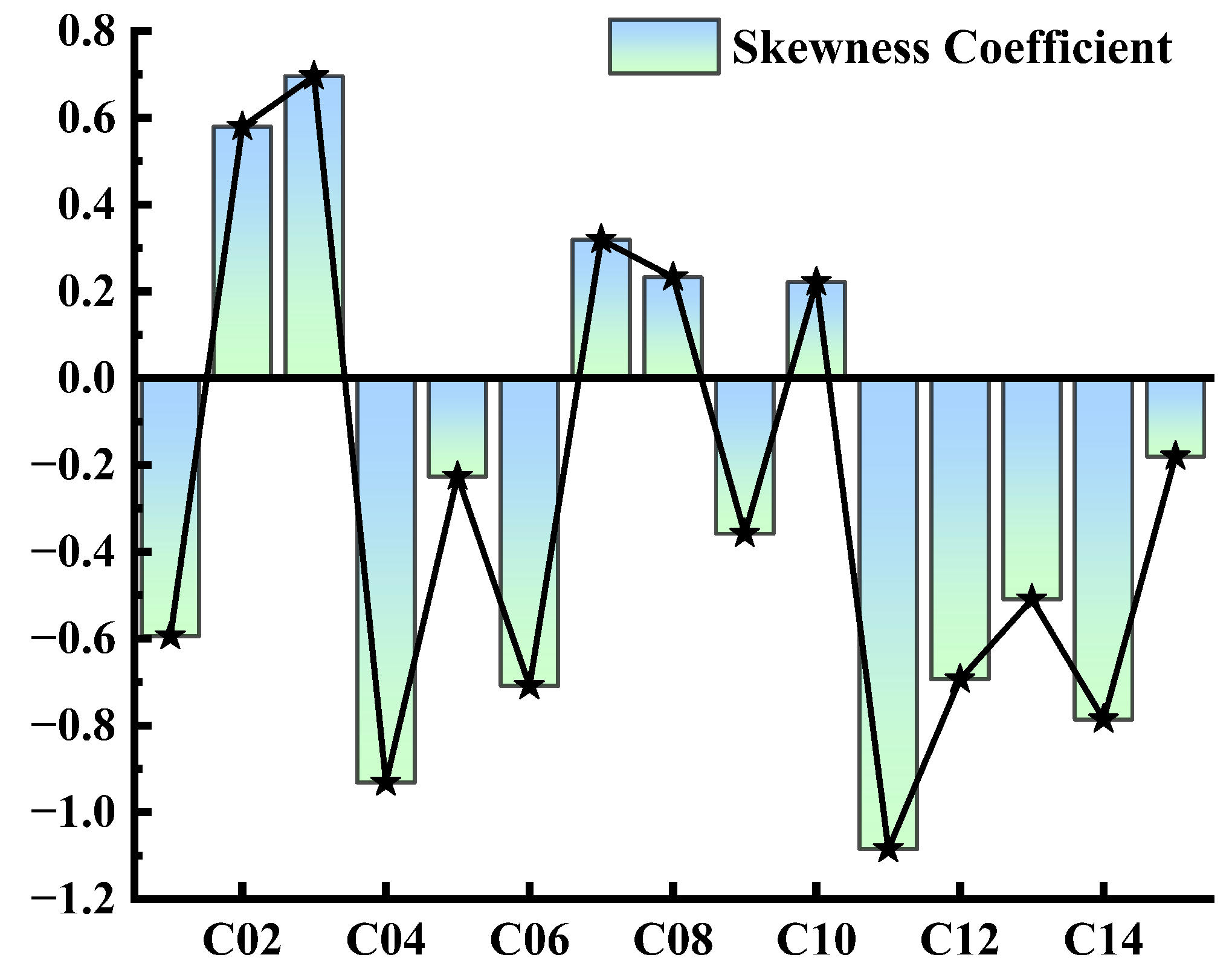

- Gaussian kernel density estimation quantitatively characterizes the skewness characteristics of velocity distribution. Sections C02–C03 around Z01 exhibit right-skewed distributions, with peaks located in the low-velocity region at 0.65–0.70 m/s, reflecting that the bifurcation-induced deceleration effect leads to an increased proportion of low-velocity flow. All sections in the spur dike-controlled reaches exhibit strong left-skewed distributions, with peaks located in the high-velocity region, indicating highly concentrated mainstream flow. The degree of velocity dispersion is negatively correlated with bed stability.

- (3)

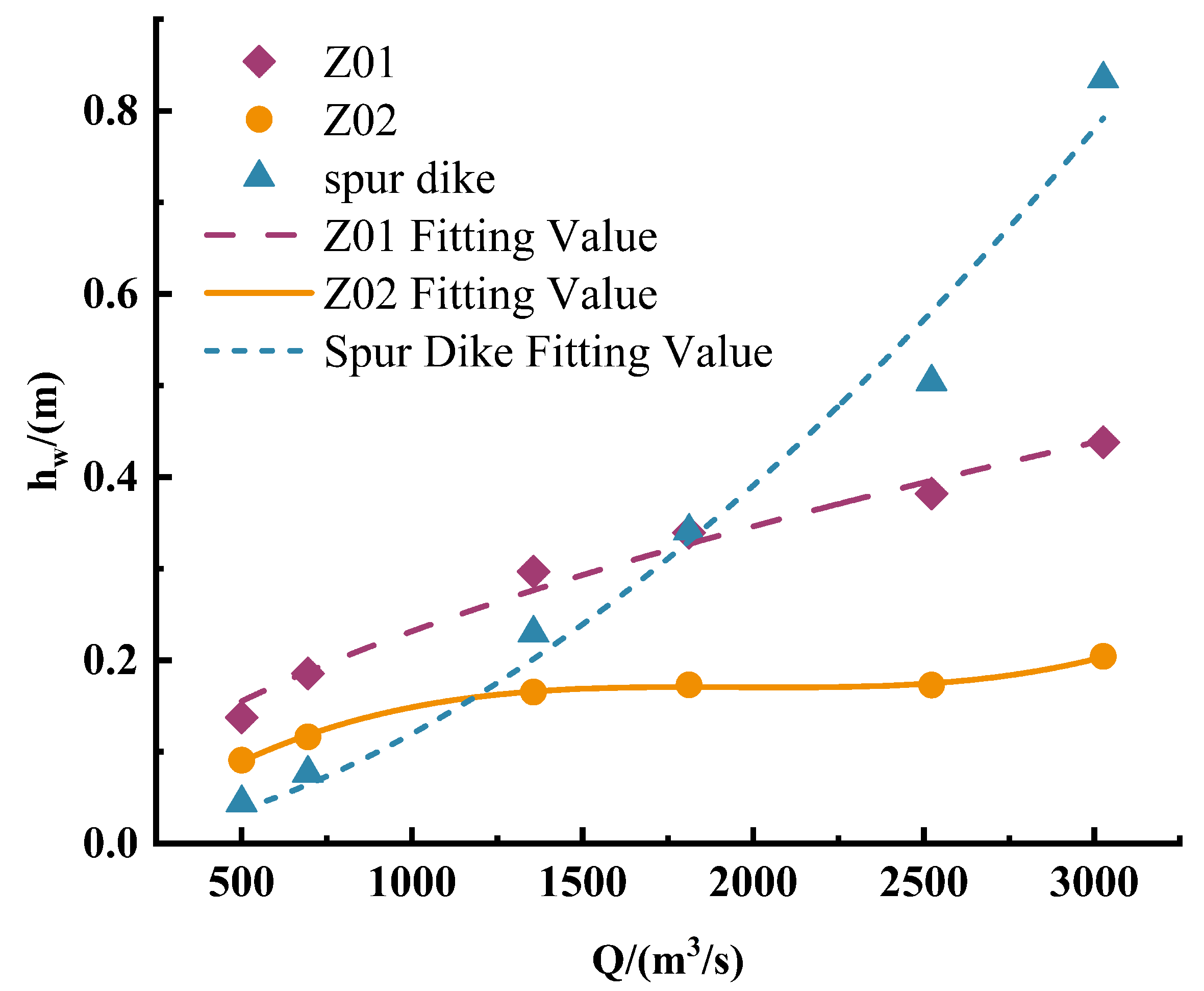

- Head loss at Z01 exhibits a diminishing marginal effect, with the marginal loss rate during the low-flow period being 2.14 times that during the high-flow period. Z02 shows polynomial growth, with an inflection point discharge of 1946 m3/s, at which the marginal loss rate approaches zero, reflecting that flow distribution reaches optimal allocation. The spur dike group exhibits superlinear growth, with the marginal loss rate increasing by 278% from the low-flow period.

- (4)

- The medium-flow period (1356–1812 ) represents the critical discharge for the bed erosion–deposition pattern. When discharge exceeds this threshold, flow velocity in the right channel of Z01 increases from less than 0.4 m/s to 0.9–1.2 m/s, and the bed transitions from deposition to erosion, with shoal body scour depth reaching 0.01 m and the deposition zone in the recirculation area at the shoal tail disappearing. During the high-flow period, the erosion–deposition pattern stabilizes, indicating that bed morphology has adapted to high-discharge conditions. Z02 exhibits a pattern of “head erosion and tail deposition”. The erosion–deposition pattern stabilizes during the high-flow period, with the spatial distributions of erosion and deposition highly coinciding between Cases 5 and 6.

- (5)

- The spur-dike series provides bank protection through a dual mechanism in the depth-averaged sense: (i) constricting the main-flow corridor and (ii) creating sheltered inter-dike low-velocity zones. During the high-flow period, flow velocity around the dike heads reaches 1.8 m/s, representing an approximately 30% increase compared to upstream conditions, while velocity within inter-dike zones decreases to below 0.2 m/s, forming a low-energy depositional environment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Deng, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Variations in channel centerline migration rate and intensity of a braided reach in the Lower Yellow River. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Li, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y. Modelling of sediment transport and bed deformation in rivers with continuous bends. J. Hydrol. 2013, 499, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Fu, C.; Zhou, T.; Yan, Z.; Li, M.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Lv, M. Current status and reflections on climate and hydrological changes in the Yellow River Basin. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 35, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, H.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Numerical study of the flow in the Yellow River with non-monotonous banks. J. Hydrodyn. 2016, 28, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yue, Z.; Tian, F.; Cao, L.; Song, T. A study of the water and sediment transport Laws and Equilibrium stability of fluvial facies in the Ningxia section of the Yellow River under variable conditions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, G.J.; Yu, G.A.; Li, Z. Geomorphic diversity of rivers in the Upper Yellow River Basin. In Landscape and Ecosystem Diversity, Dynamics and Management in the Yellow River Source Zone; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Magdaleno, F.; Fernández-Yuste, J.A. Meander dynamics in a changing river corridor. Geomorphology 2011, 130, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, J.S. The interaction between channel geometry, water flow, sediment transport and deposition in braided rivers. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1993, 75, 13–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozo, M.G.; Nogueira, A.C.; Castro, C.S. Remote sensing-based analysis of the planform changes in the Upper Amazon River over the period 1986–2006. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2014, 51, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sharma, N.; Pu, J.; Alfaisal, F.M.; Alam, S.; Khan, W.A. Analysis of turbulent flow structure with its fluvial processes around mid-channel bar. Sustainability 2021, 14, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, P.E. How do gravel-bed rivers braid? Can. J. Earth Sci. 1991, 28, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasujya, G.; Nayan, S. Spatio-temporal study of morpho-dynamics of the Brahmaputra River along its Majuli Island reach. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternack, G.B.; Baig, D.; Weber, M.D.; Brown, R.A. Hierarchically nested river landform sequences. Part 2: Bankfull channel morphodynamics governed by valley nesting structure. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 2519–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Han, J. Morphodynamic changes of braided channels caused by increased runoff and sediment flux in the Yangtze river headwater on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baubinienė, A.; Satkūnas, J.; Taminskas, J. Formation of fluvial islands and its determining factors, case study of the River Neris, the Baltic Sea basin. Geomorphology 2015, 231, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Piao, S.; Lú, Y.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y. Reduced sediment transport in the Yellow River due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, T. Recent variation in reach-scale bankfull discharge in the Lower Yellow River. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2014, 39, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corato, G.; Ammari, A.; Moramarco, T. Conventional point-velocity records and surface velocity observations for estimating high flow discharge. Entropy 2014, 16, 5546–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hsu, Y.C.; Zai, E.O. Streamflow measurement using mean surface velocity. Water 2022, 14, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Qiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Q. Probability density function of streamwise velocity fluctuation in turbulent T-junction flows. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 5005–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Zhu, H.; Fu, X.; Liang, Z. Traffic flow speed distribution based on Kernel Density Estimation. Highw. Eng. 2018, 43, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Li, W.; Xiong, X. Estimating wind speed probability distribution using kernel density method. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2011, 81, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, G.; Zhu, H.; Lu, W. Outlier Detection Method of Environmental Streams Based on Kernel Density Estimation. In Proceedings of the China Conference on Wireless Sensor Networks, Xi’an, China, 31 October–2 November 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, M. Modelling of hyperconcentrated flood and channel evolution in a braided reach using a dynamically coupled one-dimensional approach. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xia, J.; Deng, S.; Li, Z. Two-dimensional modeling of channel evolution under the influence of large-scale river regulation works. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2022, 37, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Z. Coupled two-dimensional model for heavily sediment-laden floods and channel deformation in a braided reach of the Lower Yellow River. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 131, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Cheng, K.; Luo, M.; Wang, H.; Shi, J. The effect of stress history on the critical shear stress of bedload transport in gravel-bed streams. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.A.; Guo, D.; Koster, W.M.; Lauchlan-Arrowsmith, C.; Vietz, G.J. Can hydraulic measures of river conditions improve our ability to predict ecological responses to changing flows? Flow velocity and spawning of an iconic native Australian fish. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 882495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Valyrakis, M.; Qi, M.; Sharma, A.; Lodhi, A.S. Experimental assessment and prediction of temporal scour depth around a spur dike. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2021, 36, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Xu, X.; Xia, J. Hydraulic and alluvial characteristics of the lower Yellow River after the sudden dam-break of permeable spur dikes. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2023, 34, 121–127+134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, L.K.; Eldho, T.; Raj, P.A. Temporal evolution of scour depth and hydrodynamics around T-shaped spur dikes. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 086626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.; Gondu, V.R.; Zakwan, M. Numerical simulation of scour dynamics around series of spur dikes using FLOW-3D. J. Appl. Water Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, D.; Su, M.; Ma, B.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Sun, Y. A Three-Dimensional Triangle Mesh Integration Method for Oblique Photography Model Data. Buildings 2023, 13, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.R.; Jackson, P.; Czuba, J.A.; Engel, F.; Rhoads, B.L.; Oberg, K.; Best, J.L.; Mueller, D.; Johnson, K.; Riley, J. Velocity Mapping Toolbox (VMT): A processing and visualization suite for moving-vessel ADCP measurements. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2013, 38, 1244–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, F.; Frías, M.C.; Liu, J.; Simkus, K.; Karagkiolidou, S.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Challenges with regard to Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs) measurement of river surface velocity using Doppler radar. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosronejad, A.; Limaye, A.B.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, S.; Yang, X.; Sotiropoulos, F. On the morphodynamics of a wide class of large-scale meandering rivers: Insights gained by coupling LES with sediment-dynamics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2023, 15, e2022MS003257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szupiany, R.N.; Amsler, M.L.; Parsons, D.R.; Best, J.L. Morphology, flow structure, and suspended bed sediment transport at two large braid-bar confluences. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolezzi, G.; Seminara, G. Downstream and upstream influence in river meandering. Part 1. General theory and application to overdeepening. J. Fluid Mech. 2001, 438, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, F.; Kleinhans, M.G.; Middelkoop, H. Network response to disturbances in large sand-bed braided rivers. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2016, 4, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.B.; Jerolmack, D.J. Self-organization of river channels as a critical filter on climate signals. Science 2016, 352, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, B.; Zhou, J. Physics-based numerical modelling of large braided rivers dominated by suspended sediment. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 1925–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koken, M.; Cotel, E. Numerical investigation of the coherent structures in a curved channel with a spur dike at different angles with respect to the flow directions. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 065134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyer, S.; Farzin, S.; Karami, H.; Rostami, M. A numerical and experimental investigation of the effects of combination of spur dikes in series on a flow field. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Lv, J. Effects of efficient water resource management on vegetation distribution and pattern structures. Int. J. Biomath. 2025, 2550078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, J. The delayed reaction-diffusion Filippov system with threshold control: Modeling and analysis of plateau pika-vegetation dynamics. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 152, 109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cross-Section | Water Level (m) | Maximum Depth (m) | Mean Depth (m) | Channel Width (m) | Mean Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | 1097.50 | 4.58 | 2.7387 | 364.52 | 1.6821 |

| C02 | 1097.48 | 4.14 | 2.0783 | 253.24 | 0.9551 |

| C03 | 1097.30 | 3.80 | 1.0233 | 263.65 | 0.9197 |

| C04 | 1097.14 | 3.24 | 2.2108 | 204.94 | 1.2154 |

| C05 | 1096.91 | 4.75 | 2.6042 | 407.03 | 0.7297 |

| C06 | 1096.80 | 5.08 | 2.1314 | 508.02 | 0.5338 |

| C07 | 1096.74 | 7.32 | 2.3613 | 390.31 | 0.4317 |

| C08 | 1096.51 | 7.76 | 3.3689 | 293.20 | 0.7928 |

| C09 | 1096.41 | 4.99 | 1.8284 | 336.77 | 0.8499 |

| C10 | 1096.40 | 5.41 | 2.6820 | 314.84 | 1.1903 |

| C11 | 1096.36 | 6.99 | 2.3429 | 483.92 | 1.1189 |

| C12 | 1096.34 | 6.75 | 3.2113 | 391.79 | 1.1159 |

| C13 | 1096.32 | 10.68 | 6.1668 | 216.21 | 1.1662 |

| C14 | 1096.18 | 14.88 | 5.8210 | 202.54 | 1.4332 |

| C15 | 1096.11 | 4.51 | 2.2967 | 574.72 | 0.9209 |

| Average | 1096.70 | 6.33 | 2.8577 | 347.05 | 1.0037 |

| Position | Location | D10 | D25 | D50 | D75 | D90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet | Left bank | 3.16 | 8.48 | 21.57 | 39.12 | 58.42 |

| Center | 3.29 | 9.22 | 23.78 | 43.59 | 65.60 | |

| Right bank | 2.82 | 7.30 | 18.97 | 34.24 | 51.85 | |

| Outlet | Left bank | 2.57 | 6.49 | 17.16 | 32.08 | 48.88 |

| Center | 2.71 | 6.90 | 17.81 | 33.42 | 51.57 | |

| Right bank | 2.64 | 6.77 | 16.22 | 29.37 | 45.85 | |

| Average | 2.87 | 7.53 | 19.25 | 35.30 | 53.70 |

| Shoal Type | Cross-Section Group | Right Branch Discharge (m3/s) | Discharge Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z01 | C02–C04 | 566.96 | 44.16 |

| Z02 | C06–C07 | 992.23 | 86.31 |

| Case | Period | Inlet Discharge | Outlet Water Level (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Low-flow period | 501 | 1095.78 |

| Case 2 | 695 | 1095.87 | |

| Case 3 | Normal-flow period | 1356 | 1096.11 |

| Case 4 | 1812 | 1096.37 | |

| Case 5 | High-flow period | 2523 | 1096.85 |

| Case 6 | 3026 | 1097.55 |

| Element Count | Mean Velocity (m/s) | Mean Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 3724 | 1.069 | / |

| 10,533 | 0.902 | 15.6 |

| 22,115 | 0.828 | 8.3 |

| 30,059 | 0.879 | 6.1 |

| Case | Discharge | Marginal Loss Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z01 | Z02 | Spur Dike | ||

| Case 1 | 501 | |||

| Case 2 | 695 | |||

| Case 3 | 1356 | |||

| Case 4 | 1812 | |||

| Case 5 | 2523 | |||

| Case 6 | 3026 | |||

| Case | Discharge (%) | Discharge Growth Rate (%) | Head Loss (m) | Head Loss Growth Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 501 | / | 0.045 | / |

| Case 2 | 695 | 38.7 | 0.077 | 73.1 |

| Case 3 | 1356 | 95.1 | 0.230 | 198.2 |

| Case 4 | 1812 | 57.0 | 0.341 | 48.4 |

| Case 5 | 2523 | 84.2 | 0.504 | 47.8 |

| Case 6 | 3026 | 29.7 | 0.835 | 65.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jing, H.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Lv, J. Investigation of the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Wandering Reach with Multiple Mid-Channel Shoals in the Upper Yellow River. Sustainability 2026, 18, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010264

Jing H, Li H, Wang W, Liu Y, Lv J. Investigation of the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Wandering Reach with Multiple Mid-Channel Shoals in the Upper Yellow River. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010264

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Hefang, Haoqian Li, Weihong Wang, Yongxia Liu, and Jianping Lv. 2026. "Investigation of the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Wandering Reach with Multiple Mid-Channel Shoals in the Upper Yellow River" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010264

APA StyleJing, H., Li, H., Wang, W., Liu, Y., & Lv, J. (2026). Investigation of the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of a Wandering Reach with Multiple Mid-Channel Shoals in the Upper Yellow River. Sustainability, 18(1), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010264