Driving Mechanism of Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions: An Experimental Study Based on Social Norms and Personal Norms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on the Effects of Social Norms

2.2. Research on the Factors Influencing Pro-Environmental Donations

2.3. Research Review

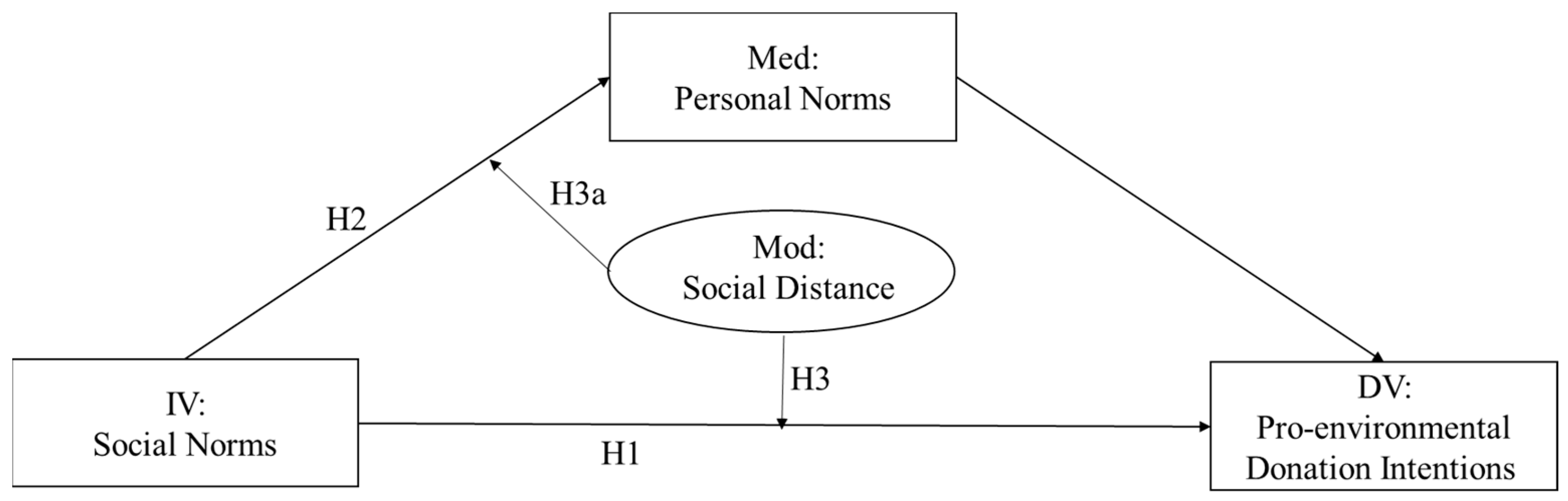

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Impact of Social Norms on Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions

3.2. Mediating Role of Personal Norms

3.3. Moderating Role of Social Distance

4. Research Method and Experimental Design

4.1. Experiment 1: Research Design and Participants

4.2. Experiment 2: Research Design and Participants

5. Analysis of the Experimental Results

5.1. Experiment 1: Analysis of Social Norms, Personal Norms, and Donation Intentions

5.1.1. Manipulation Check

5.1.2. Main Effect Analysis

5.1.3. Mediation Analysis

5.2. Experiment 2: Moderating Effect of Social Distance on the Impact of Social Norms

5.2.1. Manipulation Check

5.2.2. Main Effect Analysis

5.2.3. Mediation Effect Analysis

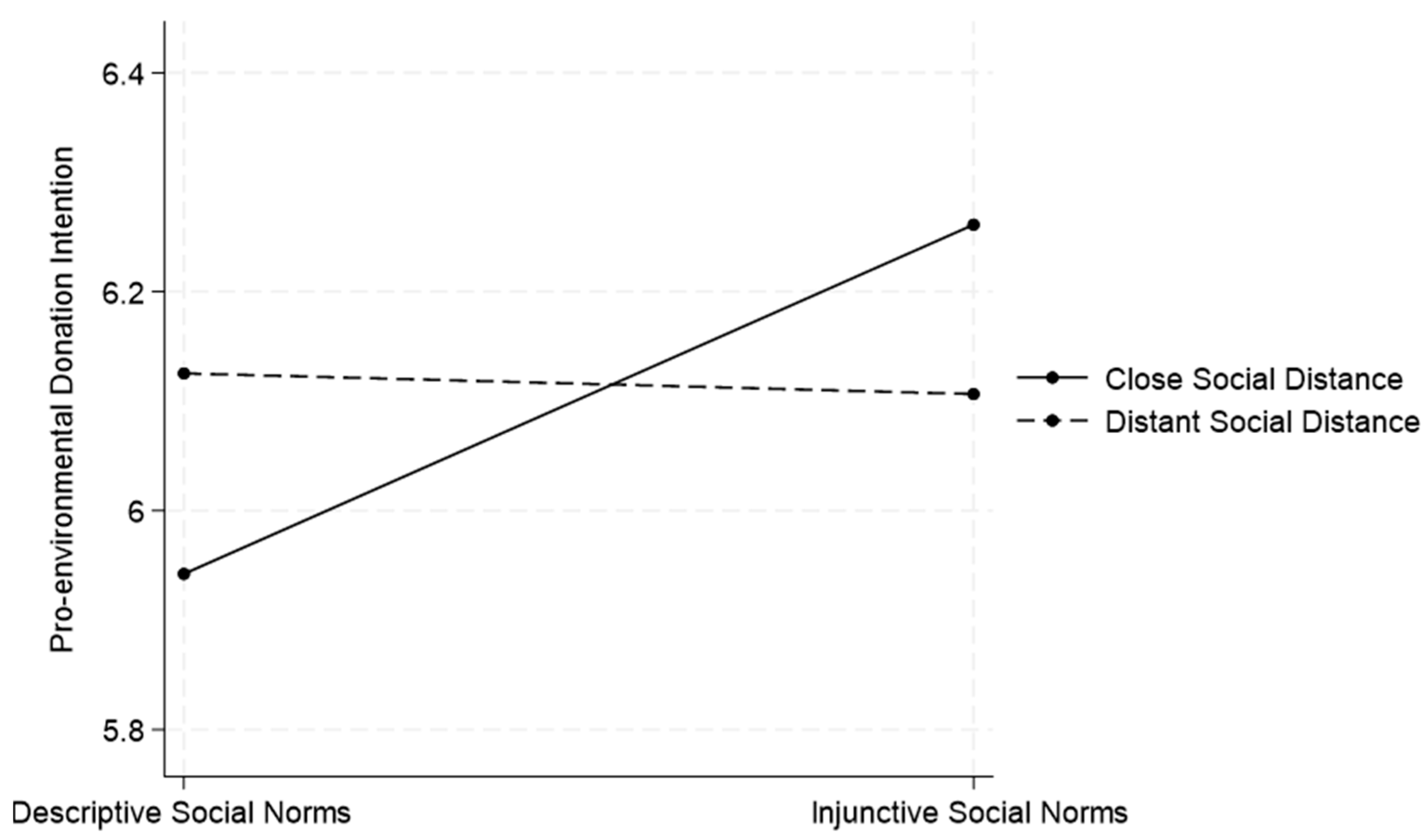

5.2.4. Moderating Effect of Social Distance

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Descriptive Social Norms Group | Injunctive Social Norms Group | p (t-Test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age | 31.54 | 8.40 | 29.79 | 6.97 | 0.19 |

| Gender | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.22 |

| Education Level | 3.09 | 0.50 | 2.97 | 0.52 | 0.19 |

| Monthly Income | 3.16 | 1.40 | 2.88 | 1.39 | 0.25 |

| Political Affiliation | 1.26 | 0.44 | 1.22 | 0.42 | 0.65 |

| Marital Status | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.21 |

| Occupation | 3.18 | 0.94 | 2.91 | 1.10 | 0.12 |

| Charitable Experience | 1.94 | 0.23 | 1.97 | 0.17 | 0.44 |

| Variables | Descriptive Social Norms Group | Injunctive Social Norms Group | p (t-Test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age | 31.94 | 8.22 | 31.38 | 8.88 | 0.53 |

| Gender | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Education Level | 2.93 | 0.69 | 3.04 | 0.62 | 0.13 |

| Monthly Income | 2.84 | 1.27 | 3.00 | 1.39 | 0.26 |

| Political Affiliation | 1.18 | 0.39 | 1.23 | 0.44 | 0.24 |

| Marital Status | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.25 |

| Occupation | 3.01 | 1.04 | 3.07 | 1.03 | 0.60 |

| Charitable Experience | 1.93 | 0.27 | 1.97 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| Donation Intentions | Donation Intentions | Personal Norms | Personal Norms | Donation Intentions | Donation Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Social Norms | 0.410 ** (0.194) | 0.493 ** (0.194) | 1.279 ** (0.537) | 1.717 *** (0.547) | 0.104 (0.156) | |

| Personal Norms | 0.242 *** (0.023) | 0.226 *** (0.024) | ||||

| Age | 0.493 ** (0.194) | 0.072 (0.052) | −0.009 (0.014) | |||

| Gender | 0.007 (0.018) | 0.556 (0.567) | −0.048 (0.157) | |||

| Education Level | 0.078 (0.202) | −0.118 (0.611) | 0.048 (0.168) | |||

| Monthly Income | 0.022 (0.217) | 0.385 (0.254) | 0.137 * (0.070) | |||

| Political Affiliation | 0.224 ** (0.090) | 0.895 (0.639) | 0.054 (0.177) | |||

| Marital Status | 0.257 (0.227) | 0.332 (0.807) | −0.001 (0.222) | |||

| Occupation | 0.074 (0.287) | 0.366 (0.297) | −0.117 (0.082) | |||

| Charitable Experience | −0.034 (0.105) | 0.103 (1.318) | 0.310 (0.362) | |||

| _cons | 5.157 *** (0.136) | 3.209 ** (1.292) | 21.900 *** (0.376) | 15.855 *** (3.638) | −0.091 (0.520) | −0.381 (1.072) |

| N | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 |

| adj.R2 | 0.025 | 0.111 | 0.033 | 0.091 | 0.449 | 0.468 |

| Donation Intentions | Donation Intentions | Personal Norms | Personal Norms | Donation Intentions | Donation Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Social Norms | 0.209 ** (0.089) | 0.154 * (0.087) | 0.730 ** (0.296) | 0.554 * (0.290) | 0.051 (0.069) | |

| Personal Norms | 0.195 *** (0.012) | 0.186 *** (0.013) | ||||

| Age | −0.003 (0.007) | −0.011 (0.024) | −0.001 (0.006) | |||

| Gender | −0.002 (0.091) | 0.121 (0.302) | −0.025 (0.072) | |||

| Education Level | −0.007 (0.074) | 0.026 (0.246) | −0.011 (0.058) | |||

| Monthly Income | 0.098 ** (0.041) | 0.302 ** (0.136) | 0.042 (0.032) | |||

| Political Affiliation | 0.104 (0.109) | 0.181 (0.363) | 0.070 (0.086) | |||

| Marital Status | 0.207 * (0.124) | 0.835 ** (0.413) | 0.052 (0.098) | |||

| Occupation | 0.034 (0.045) | −0.093 (0.148) | 0.052 (0.035) | |||

| Charitable Experience | 0.524 *** (0.194 | 1.642 ** (0.644) | 0.219 (0.154) | |||

| _cons | 6.005 *** (0.062) | 4.473 *** (0.494) | 22.491 *** (0.215) | 19.049 *** (1.771) | 1.684 *** (0.275) | 1.105 ** (0.452) |

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 |

| adj.R2 | 0.013 | 0.069 | 0.014 | 0.078 | 0.422 | 0.422 |

References

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecke, S.L.; Huber, J.; Kirchler, M.; Schwaiger, R. Nature Experiences and Pro-Environmental Behavior: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Non-Monetary Reinforcement Effects on pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2023, 97, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, K.; Anderies, J.M.; Dannenberg, A.; Lindahl, T.; Schill, C.; Schlüter, M.; Adger, W.N.; Arrow, K.J.; Barrett, S.; Carpenter, S.; et al. Social Norms as Solutions. Science 2016, 354, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venhoeven, L.; Bolderdijk, J.; Steg, L. Explaining the Paradox: How Pro-Environmental Behaviour Can Both Thwart and Foster Well-Being. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetto, G.; Gavrilets, S.; Gelfand, M.; Mace, R.; Vriens, E. Social Norm Change: Drivers and Consequences. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20230023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; Vostroknutov, A. Why Do People Follow Social Norms? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social Influence Approaches to Encourage Resource Conservation: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A Comprehensive Model of the Psychology of Environmental Behaviour—A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H. Social Norms and Energy Conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R.; Brown, E. The Influence of Descriptive Social Norm Information on Sustainable Transportation Behavior: A Field Experiment. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundaca, L.; Román-Collado, R.; Cansino, J.M. Assessing the Impacts of Social Norms on Low-Carbon Mobility Options. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Guo, X.; Fu, H. Can Social Norms Promote Recycled Water Use on Campus? The Evidence From Event-Related Potentials. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 818292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, V.T.H.; Do, L.T. The Effectiveness of Social Norms in Promoting Green Consumption. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Fu, Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Promoting Low-Carbon Purchase from Social Norms Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson, A.; Schultz, W.P. A Meta-Analysis of Field-Experiments Using Social Norms to Promote pro-Environmental Behaviors. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Estrada, M.; Schmitt, J.; Sokoloski, R.; Silva-Send, N. Using In-Home Displays to Provide Smart Meter Feedback about Household Electricity Consumption: A Randomized Control Trial Comparing Kilowatts, Cost, and Social Norms. Energy 2015, 90, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, I.; Carmon, Z.; Dhar, R.; Drolet, A.; Nowlis, S.M. Consumer Research: In Search of Identity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; He, W.; Yao, S.; Xu, Z.; Mu, Y. How We Learn Social Norms: A Three-Stage Model for Social Norm Learning. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1153809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannals, J.E.; Li, Y. A Theoretical Framework for Social Norm Perception. Res. Organ. Behav. 2024, 44, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Rimal, R.N. An Explication of Social Norms. Commun. Theory 2005, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, R.R.; Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A. The Transsituational Influence of Social Norms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannals, J.E.; Miller, D.T. Social Norm Perception in Groups with Outliers. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2017, 146, 1342–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharding, T.K.; Warren, D.E. When Are Norms Prescriptive? Understanding and Clarifying the Role of Norms in Behavioral Ethics Research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2024, 34, 331–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, R.; Handy, F.; Shang, J. Keeping up with the Joneses: The Relationship of Perceived Descriptive Social Norms, Social Information, and Charitable Giving. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2009, 19, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartke, S.; Friedl, A.; Gelhaar, F.; Reh, L. Social Comparison Nudges—Guessing the Norm Increases Charitable Giving. Econ. Lett. 2017, 152, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, S.; Rimal, R.N.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kok, G. Healthy and Unhealthy Social Norms and Food Selection. Find. A Field-Experiment. Appet. 2013, 65, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Miranda, J.J.; Price, M.K. The Persistence of Treatment Effects with Norm-Based Policy Instruments: Evidence from a Randomized Environmental Policy Experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Ekelund, M. The Role of Emotion Regulation in Normative Influence under Uncertainty. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.W.; Foerster, T.A.; Zhuang, J. Bagging a Greener Future: Social Norms Appeals and Financial Incentives in Promoting Reusable Bags Among Grocery Shoppers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, H.; Heger, S.; Olenberger, C.; Utz, L. The Effectiveness of Social Norms in Fighting Fake News on Social Media. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2021, 38, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, A. Why Should I When No One Else Does? A Review of Social Norm Appeals to Promote Sustainable Minority Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1415529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Sheng, G.; Zhang, H. How to Solve the Social Norm Conflict Dilemma of Green Consumption: The Moderating Effect of Self-Affirmation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, L.; Roussel, S. The Impact of Nature Video Exposure on Pro-Environmental Behavior: An Experimental Investigation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatola, N. The Interplay of Identity Fusion, Social Norms, and pro-Environmental Behavior: An Exploration Using the Dictator Game: Identity Fusion & Environmental Decision. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 124, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanghella, V.; d’Adda, G.; Tavoni, M. On the Use of Nudges to Affect Spillovers in Environmental Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, B.; Carrico, A.R.; Truelove, H.B. The Influence of Environmental Identity Labeling on the Uptake of Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Clim. Chang. 2019, 155, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusch, S.; Krebs, R.M.; Lange, F. Value through Cognitive Effort: Working for an Environmental Organization Increases Subsequent Donations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 107, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, L.; Moureau, N.; Roussel, S. How Do Incidental Emotions Impact Pro-Environmental Behavior? Evidence from the Dictator Game. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2017, 66, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nyström, L.; Nilsson, A. Feeling or Following? A Field-experiment Comparing Social Norms-based and Emotions-based Motives Encouraging Pro-environmental Donations. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, S.; Bernauer, T.; Ehlert, U. Stress Influences Environmental Donation Behavior in Men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.; Tok, T.Q.H.; Saad, C.S.; Kim, H.S. Religion, Environmental Guilt, and pro-Environmental Support: The Opposing Pathways of Stewardship Belief and Belief in a Controlling God. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemo, K.H.; Nigus, H.Y. Does Religion Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviour? A Cross-Country Investigation. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzej Lipinski, P.; Kunkle, S.; Lange, F. Effects of Financial Incentives on Pro-Environmental Behavior before and after Incentive Discontinuation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 105, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Lower Perceived Economic Mobility Inhibits Pro-Environmental Engagement by Increasing Cynicism. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2025, 16, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, K.; Pummerer, L.; Sassenberg, K. Not That Different after All: Pro-environmental Social Norms Predict Pro-environmental Behaviour (Also) among Those Believing in Conspiracy Theories. Br. J. Psychol. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, C.; Qin, J.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y. Working-Together Normative Appeals to Promote Pro-Environmental Donations. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A. How Anonymity and Norms Influence Costly Support for Environmental Causes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 58, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhong, Y. Environmental Protection or Self-Interest? The Public Accountability Moderates the Effects of Materialism and Advertising Appeals on the Pro-Environmental Behavior. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Blankenberg, A.-K. Green Lifestyles and Subjective Well-Being: More about Self-Image than Actual Behavior? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 137, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, K.; Simpson, B. Do Descriptive Norms Solve Social Dilemmas? Conformity and Contributions in Collective Action Groups. Soc. Forces 2013, 91, 1057–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Nakayachi, K. When Descriptive Norms Backfire: Attitudes Induce Undesirable Consequences during Disaster Preparation. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2020, 20, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, N.L.; Luke, D.M.; Gawronski, B. Thinking About Reasons for One’s Choices Increases Sensitivity to Moral Norms in Moral-Dilemma Judgments. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2023, 51, 01461672231180760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fieldhouse, E.; Cutts, D.; Bailey, J. Who Cares If You Vote? Partisan Pressure and Social Norms of Voting. Political Behav. 2022, 44, 1297–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, A.; Sassenberg, K.; Pfattheicher, S. Pressured to Be Excellent? Social Identification Prevents Negative Affect from High University Excellence Norms. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 84, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. ISBN 978-0-12-015210-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoldo, R.; Castro, P. The Outer Influence inside Us: Exploring the Relation between Social and Personal Norms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.; Carrasquer, G.; Rehm, W.S. Effect of Reduced pH in Absence of HCO3− on Anomalous and Normal Potential Responses in Bullfrog Antrum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 1984, 773, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözer, E.G.; Civelek, M.E.; Ertemel, A.V.; Pehlivanoğlu, M.Ç. The Determinants of Green Purchasing in the Hospitality Sector: A Study on the Mediation Effect of LOHAS Orientation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoushy, S.; Ribeiro, M.A. Socially Responsible Consumers and Stockpiling during Crises: The Intersection of Personal Norms and Fear. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, Y.; Scott, M. Social Media Activation of Pro-Environmental Personal Norms: An Exploration of Informational, Normative and Emotional Linkages to Personal Norm Activation. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Estrada-Mejia, C.; Rosa, J.A. Norm-Focused Nudges Influence pro-Environmental Choices and Moderate Post-Choice Emotional Responses. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. The Role of Construal Level in Message Effects Research: A Review and Future Directions. Commun. Theory 2019, 29, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, E.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The Effects of Time Perspective and Level of Construal on Social Distance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, S.; Lin, Y.; Bai, L. Closer People Hurt You More: How Social Distance Modulates Deception-Triggered Trust Decline and Trust Repair. Int. J. Psychol. 2025, 60, e70095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepaniak, Z.; Gaboriaud, A.; Quinton, J.-C.; Smeding, A. The Effects of Social Distance and Gender on Moral Decisions and Judgments: A Reanalysis, Replication, and Extension Of. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 55, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. How Perceived Social Distance and Trust Influence Reciprocity Expectations and eWOM Sharing Intention in Social Commerce. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Chen, G.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, S. Closer Is Not Always More Credible: The Effect of Social Distance on Misinformation Processing. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2025, 39, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ma, W.; Wu, J. Fostering Voluntary Compliance in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analytical Framework of Information Disclosure. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Nee, V.; Holm, H. Cooperation with Strangers: Spillover of Community Norms. Organ. Sci. 2023, 34, 2315–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Shen, B. Effects of Two Face Regulatory Foci About Ethical Fashion Consumption in a Confucian Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 196, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, D.; Gutsche, G.; Simixhiu, A.; Ziegler, A. Social Norms and Individual Climate Protection Activities: A Survey Experiment for Germany. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The Roles of Values and Social Norm on Personal Norms and Pro-Environmentally Friendly Apparel Product Purchasing Behavior: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, N.; Fan, W.; Ren, M.; Li, M.; Zhong, Y. The Role of Social Norms and Personal Costs on Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J. Increased Social Distance Makes People More Risk-Neutral. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 157, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, Y.; Xia, L.; Xu, B.; Syed Abdullah, S.M. The Effects of Social Distance and Asymmetric Reward and Punishment on Individual Cooperative Behavior in Dilemma Situations. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 816168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortega, B. Don’t Believe Strangers: Online Consumer Reviews and the Role of Social Psychological Distance. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corniciuc, I.; Lotti, L.; Ferrini, S.; Ceausu, S. Spatial Scale Effects on Environmental Donations: Evidence from a Revised Dictator Game Experiment with Real Payments. Ecol. Econ. 2026, 240, 108794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, T.K.G.; Welsch, H.; Ziegler, A. The Relationship between Climate Protection Activities, Economic Preferences, and Life Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence for Germany. Energy Econ. 2023, 128, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leardini, C.; Rossi, G.; Landi, S. Organizational Factors Affecting Charitable Giving in the Environmental Nonprofit Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. Altruistic Behavior for Environmental Conservation and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from 37 Nations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 6005–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Liang, D.; Hong, M. Shaping Future Generosity: The Role of Injunctive Social Norms in Intertemporal pro-Social Giving. J. Econ. Psychol. 2024, 102, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihani, N.J.; McAuliffe, K. Dictator Game Giving: The Importance of Descriptive versus Injunctive Norms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A.; Hinchcliff, M.; Papakosmas, M.; Hughes, G.; Heffernan, T. Norms-Driven Behaviour Change for GHG Reduction: A Meta-Analytic Review of High and Low Involvement Behaviours. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 23, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, R.; Rottman, J.; Crimston, C.R. Moral Expansiveness and Pro-Environmentalism: The Mediating Role of Moral Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 2025, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, J.; Bruns, S. Social Distancing in Times of Corona: A Longitudinal Study on the Role of (Mass Media-) Communication for Perceived Social Distancing Norms. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2025, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Variable | N | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Descriptive Social Norm | 70 | 6.11 | 0.71 | 3.60 | 0.00 |

| Injunctive Social Norm | 67 | 5.33 | 1.67 |

| Experiment | Variable | N | Donation Intentions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | t | p | |||

| Experiment 1 | Descriptive Social Norm | 70 | 5.16 | 1.12 | −2.11 | 0.036 |

| Injunctive Social Norm | 67 | 5.57 | 1.14 | |||

| Donation Intentions | ||

|---|---|---|

| bs1 | bs2 | |

| Constant | 0.39 | 0.10 |

| Z-value | 3.00 | 0.67 |

| p-value | 0.03 | 0.50 |

| Confidence Interval | (0.13, 0.64) | (−0.20, 0.41) |

| N | 137 | 137 |

| Experiment | Variable | N | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 2 | Descriptive Social Norm | 183 | 5.85 | 1.00 | 6.91 | 0.00 |

| Injunctive Social Norm | 177 | 4.85 | 1.66 |

| Experiment | Variable | N | Donation Intentions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | t | p | |||

| Experiment 2 | Close Social Distance | 185 | 23.52 | 2.54 | 2.35 | 0.02 |

| Distant Social Distance | 175 | 22.86 | 2.80 | |||

| Experiment | Variable | N | Donation Intentions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | t | p | |||

| Experiment 2 | Descriptive Social Norm | 183 | 6.00 | 0.90 | −2.36 | 0.02 |

| Injunctive Social Norm | 177 | 6.21 | 0.77 | |||

| Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions | ||

|---|---|---|

| bs1 | bs2 | |

| Constant | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| Z-value | 2.36 | 1.01 |

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| Confidence Interval | (0.02, 0.26) | (−0.06, 0.20) |

| N | 360 | 360 |

| Donation Intentions | Donation Intentions | Personal Norms | Personal Norms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Social Norms | 0.379 *** (0.123) | 0.319 *** (0.121) | 1.209 *** (0.412) | 1.045 *** (0.402) |

| Social Distance | 0.208 * (0.124) | 0.183 (0.121) | 0.220 (0.414) | 0.179 (0.402) |

| Social Norms × Social Distance | −0.349 ** (0.177) | −0.338 * (0.172) | −0.993 * (0.591) | −1.016 * (0.573) |

| Age | −0.003 (0.007) | −0.011 (0.024) | ||

| Gender | −0.003 (0.091) | 0.079 (0.303) | ||

| Education Level | −0.007 (0.074) | 0.035 (0.245) | ||

| Monthly Income | 0.095 ** (0.041) | 0.298 ** (0.136) | ||

| Political Affiliation | 0.102 (0.109) | 0.188 (0.361) | ||

| Marital Status | 0.210 * (0.124) | 0.865 ** (0.412) | ||

| Occupation | 0.028 (0.045) | −0.107 (0.148) | ||

| Charitable Experience | 0.522 *** (0.193) | 1.616 ** (0.642) | ||

| _cons | 5.903 *** (0.087) | 4.414 *** (0.495) | 22.258 *** (0.290) | 18.135 *** (1.645) |

| N | 360 | 360 | 360 | 360 |

| adj.R2 | 0.018 | 0.074 | 0.018 | 0.084 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Yan, K. Driving Mechanism of Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions: An Experimental Study Based on Social Norms and Personal Norms. Sustainability 2026, 18, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010268

Zhang S, Yan K. Driving Mechanism of Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions: An Experimental Study Based on Social Norms and Personal Norms. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Siya, and Kegao Yan. 2026. "Driving Mechanism of Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions: An Experimental Study Based on Social Norms and Personal Norms" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010268

APA StyleZhang, S., & Yan, K. (2026). Driving Mechanism of Pro-Environmental Donation Intentions: An Experimental Study Based on Social Norms and Personal Norms. Sustainability, 18(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010268