Full-Scale Efficient Production and Economic Analysis of SCFAs from UPOW and Its Application as a Carbon Source for Sustainable Wastewater Biological Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. UPOW, Inoculated Sludge, and Municipal Wastewater

2.2. Optimization of pH Value and Time for Anaerobic Fermentation of Organic Slurry of UPOW to Produce SCFAs in Laboratory Reactors

2.3. Full-Scale Organic Slurry Preparation from UPOW and SCFAs-Enriched Fermentation Liquid Production from Organic Slurry

2.4. The Influence of Fermentation Liquid Dosage and Nitrogen and Phosphorus Present in Fermentation Liquid on Municipal Wastewater BNR in Laboratory Reactors

2.5. Full-Scale Municipal Wastewater Treatment with SCFAs-Enriched Fermentation Liquid as an Additional Carbon Source

2.6. Comparison of Short-Cut Nitrification–Denitrification Capacity Between SA-AAO and FL-AAO Biomasses

2.7. Analytical Methods

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mass Balance and Properties of Organic Slurry Generated from UPOW Pretreatment

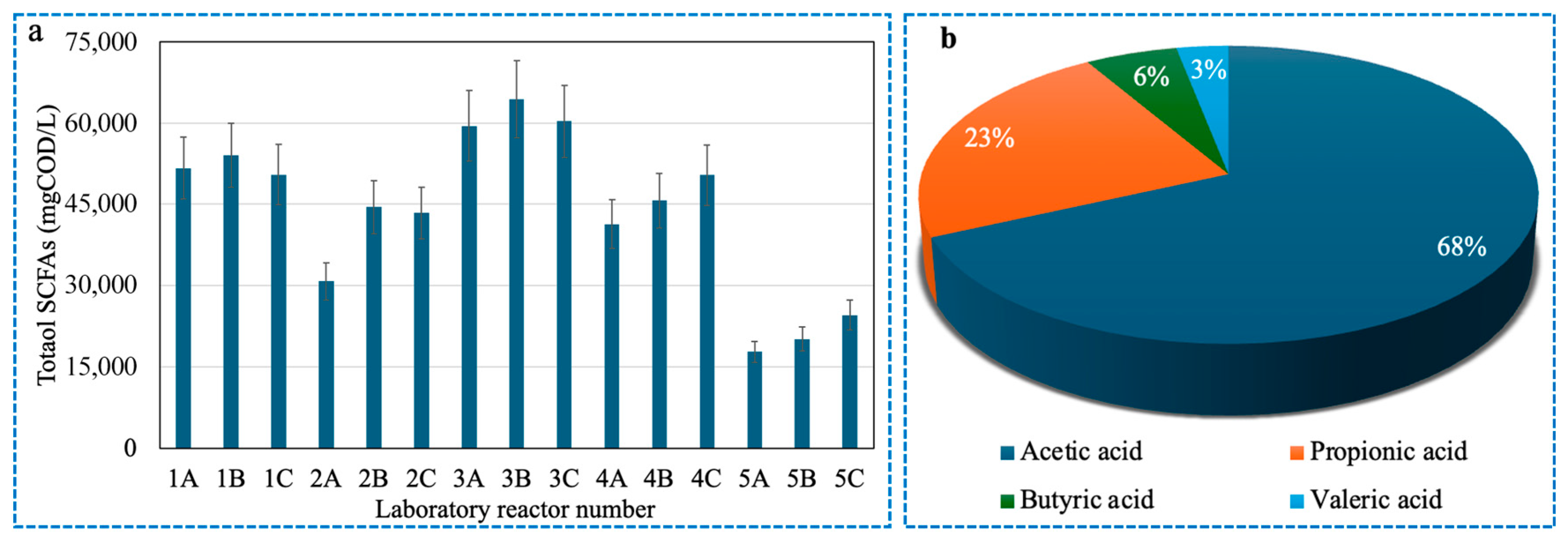

3.2. The Optimal pH Value and Reaction Time for SCFAs Production from Organic Slurry

3.3. Full-Scale Organic Slurry Preparation and SCFAs-Enriched Fermentation Liquid Production

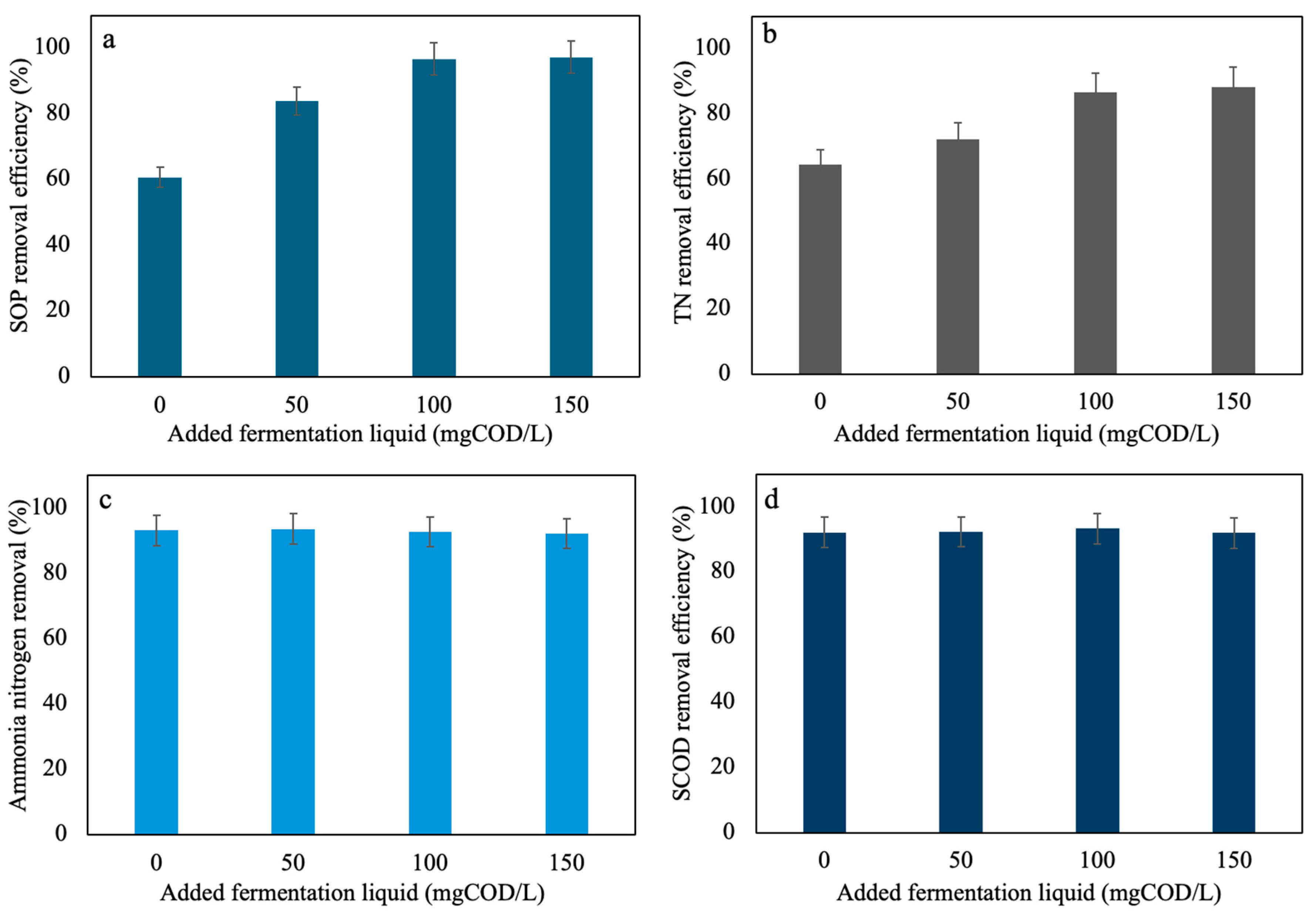

3.4. The Influence of SCFAs-Enriched Fermentation Liquid on Wastewater BNR

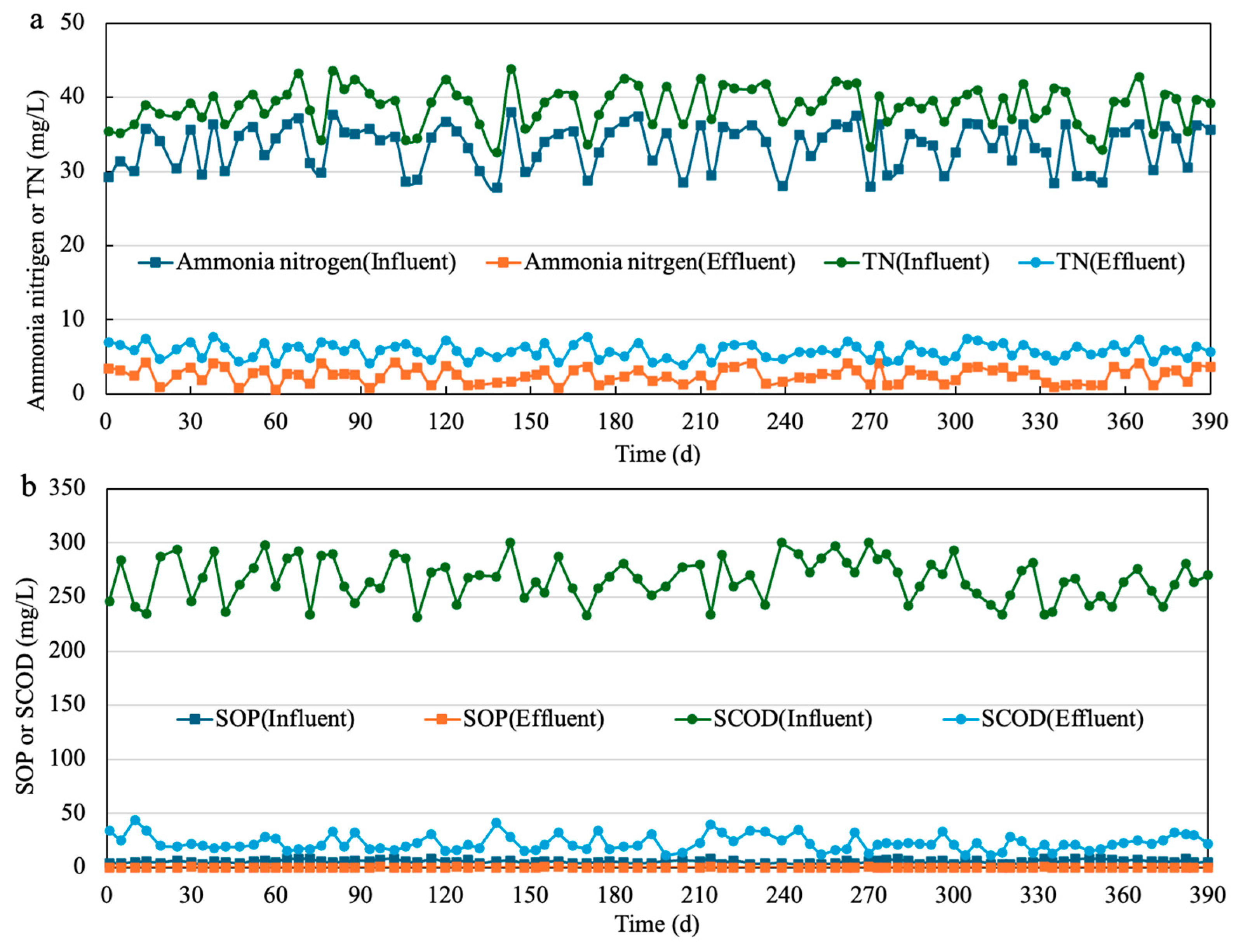

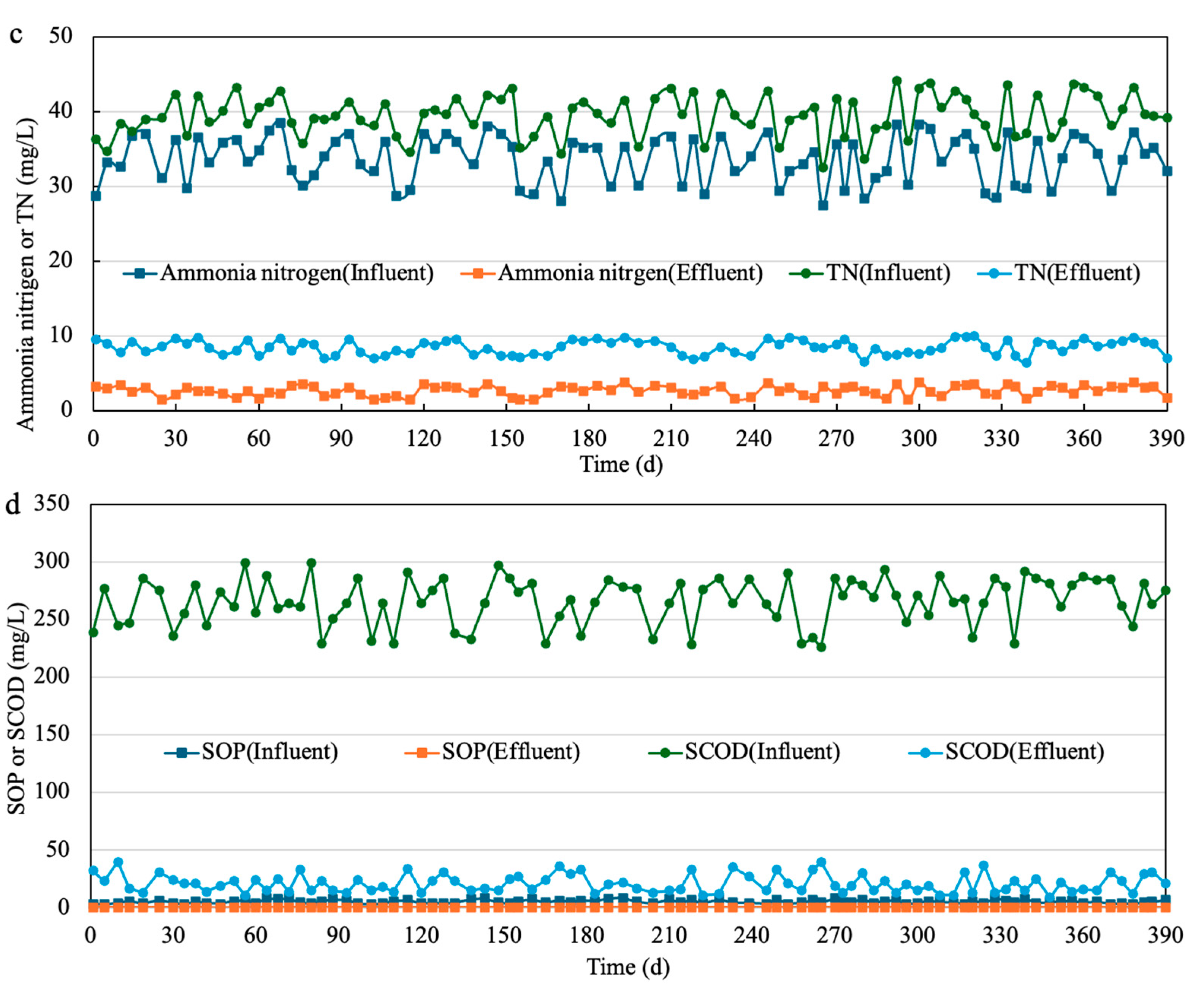

3.5. Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment with SCFAs-Enriched Fermentation Liquid as Additional Carbon Source

3.6. Economic Benefit Analysis of the Actual Operation Process of UPOW Producing SCFAs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. State of Food and Agriculture. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Jana, R.; Ikbal, S.; Chowdhury, R. Boosting of energy efficiency and by-product quality of anaerobic digestion of kitchen waste: Hybridization with pyrolysis using zero-waste strategy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 324, 119290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Lee, Y.Y.; Fan, C.; Chung, Y.C. Recycling of domestic sludge cake as the inoculum of anaerobic digestion for kitchen waste and its benefits to carbon negativity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ekama, M.G.A.; Brdjanovic, D. Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design, 2nd ed.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maheepala, S.S.; Fuchigami, S.; Hatamoto, M.; Akashi, T.; Watari, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Stable denitrification performance of a mesh rotating biological reactor treating municipal wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 27, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.F.; Guo, H.F. Influence of additional methanol on both pre- and post-denitrification processes in treating municipal wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Shan, Z.; Pan, T.; Huang, Z.; Ruan, W. Characteristics of volatile fatty acids production and microbial succession under acid fermentation via anaerobic membrane bioreactor treating kitchen waste slurry. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 429, 132502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rózsenberszki, T.; Kalauz-Simon, V.; Fejes, R.; Bakonyi, P.; Koók, L.; Kurdi, R.; Nemestóthy, N.; Bélafi-Bakó, K. Carboxylic acid production from kitchen waste and sewage sludge digestate inoculation via acidogenic fermentation at high organic load. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025, 16, 3733–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, Z.; Li, B.; Sun, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, H.; Xie, J.; Hu, Y.; Su, Y.; et al. Novel insights into liquid digestate-derived hydrochar enhances volatile fatty acids production from anaerobic co-digestion of sludge and food waste. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Nan, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L. Enhanced SCFAs production from waste activated sludge by ultrasonic pretreatment with enzyme-assisted anaerobic fermentation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.C.; Olsson, J.; Malovanyy, A.; Baresel, C.; Machamada-Devaiah, N.; Schnürer, A. Impact of thermal hydrolysis on VFA-based carbon source production from fermentation of sludge and digestate for denitrification: Experimentation and upscaling implications. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grana, M.; Catenacci, A.; Ficara, E. Denitrification capacity of volatile fatty acids from sludge fermentation: Lab-scale testing and full-scale assessment. Fermentation 2024, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, A.; Xu, Q.; He, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, A. Short-chain fatty acid production from waste activated sludge and in situ use in wastewater treatment plants with life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossiansson, E.; Bengtsson, S.; Persson, F.; Cimbritz, M.; Gustavsson, D.J.I. Primary filtration of municipal wastewater with sludge fermentation—Impacts on biological nutrient removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arhin, S.G.; Cesaro, A.; Di Capua, F.; Esposito, G. Acidogenic fermentation of food waste to generate electron acceptors and donors towards medium-chain carboxylic acids production. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. The enhancement of caproic acid synthesis from organic solid wastes: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, T.; Feng, L.; Chen, Y. The mechanisms of pH regulation on promoting volatile fatty acids production from kitchen waste. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Zhang, W.S.; Qi, S.; Zhao, J.F.; Sun, Z.Y.; Tang, Y.Q. Anaerobic volatile fatty acid production performance and microbial community characteristics from solid fraction of alkali-thermal treated waste-activated sludge: Focusing on the effects of different pH conditions. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 4565–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatkiewicz, J.; Slezak, R.; Krzystek, L.; Ledakowicz, S. Production of volatile fatty acids in a semi-continuous dark fermentation of kitchen waste: Impact of organic loading rate and hydraulic retention time. Energies 2021, 14, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X. Enhancement of waste activated sludge protein conversion and volatile fatty acids accumulation during waste activated sludge anaerobic fermentation by carbohydrate substrate addition: The effect of pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4373–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannakham, S.; Yang, S. Enhanced propionic acid fermentation by Propionibacterium acidipropionici mutant obtained by adaptation in a fibrous-bed bioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 91, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, X.; Feng, L. Short-chain fatty acid production from different biological phosphorus removal sludges: The Influences of PHA and gram- staining bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2688–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 20th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, D.L. Quantitative determination of carbohydrates with Dreywood’s anthrone reagent. Science 1948, 107, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.C.; Snoeyink, V.L.; Crittenden, J.C. Activated carbon adsorption of humic substances. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 1981, 73, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, Y.; Zeeman, G.; van Lier, J.B.; Lettinga, G. The role of sludge retention time in the hydrolysis and acidification of lipids, carbohydrates and proteins during digestion of primary sludge in CSTR systems. Water Res. 2000, 34, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, X.; Feng, L. Long-term effects of copper nanoparticles on wastewater biological nutrient removal and N2O generation in the activated sludge process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12452–12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Gu, G. The effect of propionic to acetic acid ratio on anaerobic-aerobic (low dissolved oxygen) biological phosphorus and nitrogen removal. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4400–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Li, N.; Zou, P.; Gao, X.; Cao, Q. Nitrogen removal performances and metabolic mechanisms of denitrification systems using different volatile fatty acids as external carbon sources. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Chen, Y. Using sludge fermentation liquid to improve wastewater short-cut nitrification-denitrification and denitrifying phosphorus removal via nitrite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8957–8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wan, R.; Zheng, X.; Liu, K. The effects of fulvic acid on microbial denitrification: Promotion of NADH generation, electron transfer, and consumption. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5607–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigger, G.T.; Bowen, P.T. Economic considerations on the use of fermenters in biological nutrient removal systems. Use of fermentation to enhance biological nutrient removal. In Proceedings of the Conference Seminar, 67th Annual Water Environment Federation Conference & Exposition, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–19 October 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak, R.I. Principles and Practice of Phosphorus and Nitrogen Removal from Municipal Wastewater; Lewis Publishers: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Reactor | Group | pH | Daily Renewed Mixture Volume (L) | Corresponding Reaction Time (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 1 | 6 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 4 |

| 1B | 2 | 3 | ||

| 1C | 3 | 2 | ||

| 2A | 2 | 7 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 4 |

| 2B | 2 | 3 | ||

| 2C | 3 | 2 | ||

| 3A | 3 | 8 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 4 |

| 3B | 2 | 3 | ||

| 3C | 3 | 2 | ||

| 4A | 4 | 9 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 4 |

| 4B | 2 | 3 | ||

| 4C | 3 | 2 | ||

| 5A | 5 | - ** | 1.5 | 4 |

| 5B | 2 | 3 | ||

| 5C | 3 | 2 |

| Reactor | Activity of AK (U/100 mg VSS) | Activity of CoAT (U/100 mg VSS) | SCFAs Production (mg COD/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 5.332 ± 0.287 | 3.042 ± 0.311 | 54,046 ± 4358 |

| 2B | 3.147 ± 0.216 | 1.264 ± 0.156 | 44,505 ± 3874 |

| 3B | 8.465 ± 0.422 | 5.323 ± 0.427 | 64,367 ± 4895 |

| 4C | 4.563 ± 0.301 | 1.788 ± 0.179 | 50,375 ± 4011 |

| 5C | 1.345 ± 0.115 | 0.631 ± 0.072 | 24,587 ± 1978 |

| NH4+-N (%) | TN (%) | SOP (%) | SCOD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL-AAO | 93.8 ± 3.4 | 88.1 ± 5.2 | 96.9 ± 3.1 | 92.4 ± 2.3 |

| SA-AAO | 93.0 ± 2.9 | 81.4 ± 4.5 | 91.5 ± 2.8 | 93.1 ± 1.9 |

| Item | Cost or Benefit (¥/t) |

|---|---|

| Input | |

| Labor cost | 26.34 |

| Water and electricity bills | 9.32 |

| NaOH and HCl consumption | 6.24 |

| Equipment testing and maintenance | 7.86 |

| Garbage collection and transportation | 110 |

| Miscellaneous property expenses | 8.56 |

| Total | 168.32 |

| Output | |

| Crude oil | 168 |

| Solid waste after three-phase separation | 5.76 |

| SCFAs-enriched fermentation liquid | 156 |

| Total | 329.76 |

| Net income | 161.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X. Full-Scale Efficient Production and Economic Analysis of SCFAs from UPOW and Its Application as a Carbon Source for Sustainable Wastewater Biological Treatment. Sustainability 2026, 18, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010262

Chen Y, Dong L, Zhang X. Full-Scale Efficient Production and Economic Analysis of SCFAs from UPOW and Its Application as a Carbon Source for Sustainable Wastewater Biological Treatment. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010262

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yuxi, Lei Dong, and Xin Zhang. 2026. "Full-Scale Efficient Production and Economic Analysis of SCFAs from UPOW and Its Application as a Carbon Source for Sustainable Wastewater Biological Treatment" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010262

APA StyleChen, Y., Dong, L., & Zhang, X. (2026). Full-Scale Efficient Production and Economic Analysis of SCFAs from UPOW and Its Application as a Carbon Source for Sustainable Wastewater Biological Treatment. Sustainability, 18(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010262