How Existing Infrastructure and Governance Arrangement Affect the Development of Sustainable Wastewater Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Local Government, Infrastructure, and Sustainability Transitions

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Sanitation in The Netherlands

3. Research Design

4. Results

4.1. What Changes Were Envisioned?

4.2. Case 1: Phosphorus Removal

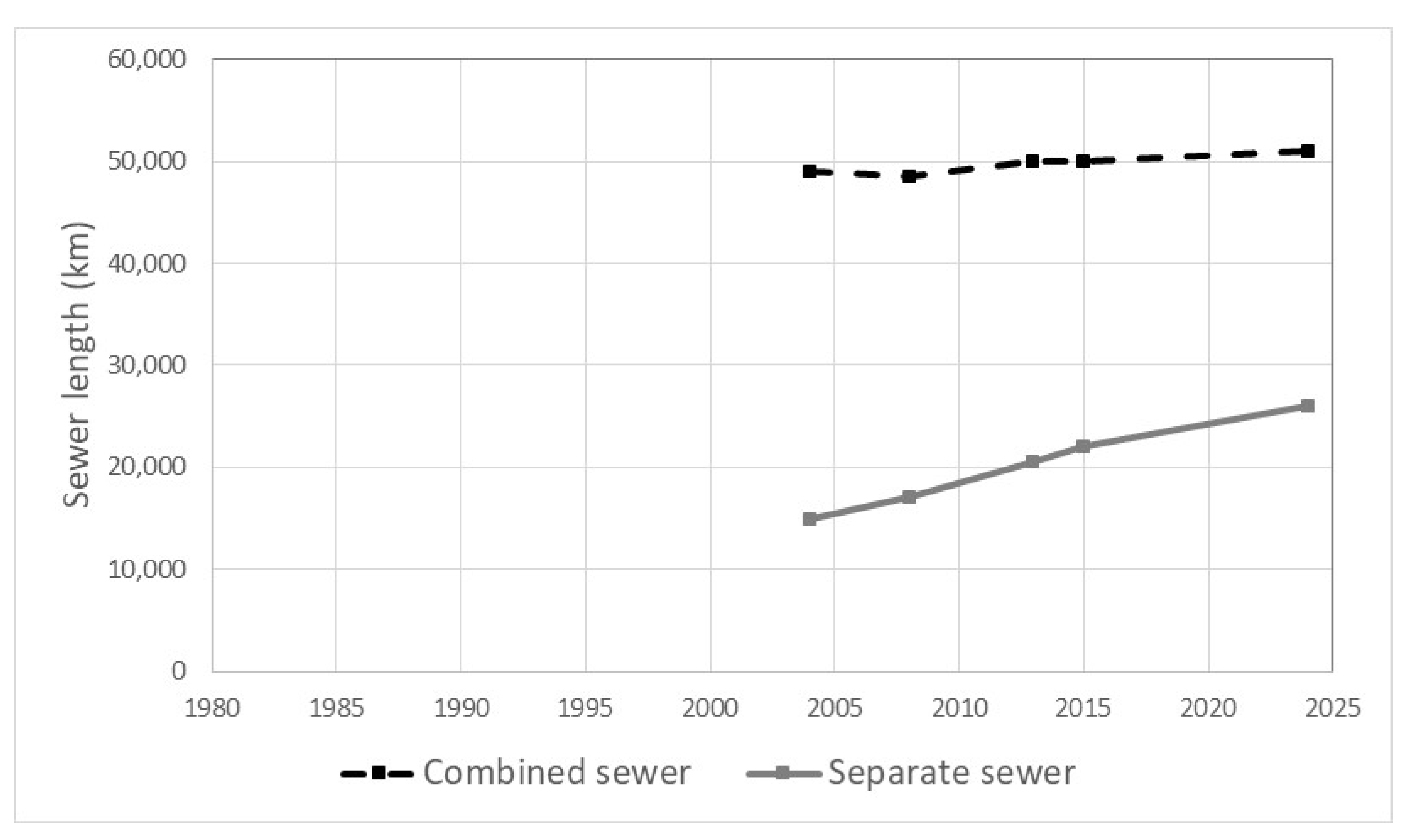

4.3. Case 2: Separation of Stormwater and Municipal Wastewater

4.4. Case 3: Water Cycle Companies

4.5. Case 4: Energy Factories

4.6. Case 5: Decentralised Sanitation

5. Discussion

5.1. Change in Relation to the Governance Arrangement and Infrastructure

5.2. Agency by (Local) Government

5.3. The Question of Coordination

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DWA | Dutch Water Authorities |

| EU | European Union |

| HHR | Hoogheemraadschap Rijnland (a Dutch RWA) |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| NPM | New Public Management |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| P-removal | Phosphorus removal |

| RWA | Regional Water Authority |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

References

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy Spec. Sect. Sustain. Transit. 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. Transition Studies: Basic Ideas and Analytical Approaches. In Handbook on Sustainability Transition and Sustainable Peace, Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace; Brauch, H.G., Oswald Spring, Ú., Grin, J., Scheffran, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. Understanding transitions from a governance perspective. In Transitions to Sustainable Development. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Regime Resistance against Low-Carbon Transitions: Introducing Politics and Power into the Multi-Level Perspective. Theory Cult. Soc. 2014, 31, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Scully, M. The Institutional Entrepreneur as Modern Prince: The Strategic Face of Power in Contested Fields. Organ. Studies 2007, 28, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dokkum, H.P.; Loeber, A.M.C.; Grin, J. Understanding the role of government in sustainability transitions: A conceptual lens to analyse the Dutch gas quake case. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 194, 122685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, P.; Newell, P. Sustainability transitions and the state. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The New Governance: Governing without Government. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. The State: Past, Present, Future; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. Pathways towards improved water governance: The role of polycentric governance systems and vertical and horizontal coordination. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 144, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.-B.; Newig, J. Importance of Actors and Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic Exploration of the Literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, M. The Role of Cities in Sustainability Transitions: New Perspectives for Science and Policy. In Quantitative Regional Economic and Environmental Analysis for Sustainability in Korea, New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives; Kim, E., Kim, B.H.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Shiroyama, H. The Challenge of Sustainable Urban Development and Transforming Cities. In Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions: European and Asian Experiences, Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Lockwood, M.; Mitchell, C.; Hoggett, R. Governing for sustainable energy system change: Politics, contexts and contingency. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C. Re-scaling IPE: Local government, sustainable energy and change. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2019, 26, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunio, V.; Argamosa, P.; Caswang, J.; Vinoya, C. The State in the governance of sustainable mobility transitions in the informal transport sector. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 38, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. ‘Doing’ system innovations from within the heart of the regime. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudge, S.; Peters, M.; Woodman, B. Local authorities as niche actors: The case of energy governance in the UK. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naschold, F. New Frontiers in the Public Sector Management: Trends and Issues in State and Local Government in Europe, Reprint 2017 ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, F.J.; Rogers, B.C.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Brown, R.R. Transitions through a lens of urban water. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbit, C. Governance of Public Policies in Decentralised Contexts: The Multi-level Approach (OECD Regional Development Working Papers No. 2011/04); OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-Level Approach; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, F.; Kern, F.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Maschmeyer, S.; Egermann, M. Urban sustainability transitions in a context of multi-level governance: A comparison of four European states. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 26, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Malekpour, S.; Mintrom, M. Cross-scale, cross-level and multi-actor governance of transformations toward the Sustainable Development Goals: A review of common challenges and solutions. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.W. Mult-level games. In Handbook on Multi-Level Governance; Enderlein, H., Walti, L., Zurn, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, K.F. Future options for sewage and drainage systems three scenarios for transitions and continuity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedby, N.; Quitzau, M.-B. Municipal Governance and Sustainability: The Role of Local Governments in Promoting Transitions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Britton, J. Policy, politics and materiality across scales: A framework for understanding local government sustainable energy capacity applied in England. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, I.; Duyvendak, J.W. Understanding governmental activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2017, 16, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioned. Monitor Gemeentelijke Watertaken 2024; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://rioned-web-prod.azurewebsites.net/media/lq2ek3dm/monitor-gemeentelijke-watertaken-2024-webversie-maart-2025.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Ambient, 2024. Landelijke Visie, Strategie en Uitvoeringsagenda Voor de Waterketen Richting 2050. Utrecht, The Netherlands. Available online: https://unievanwaterschappen.nl/wp-content/uploads/Visie-en-strategie-waterketen-11-december-defintief.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Meijer, H.; van Leeuwen, J.; Jansen, L.; Bakker, C.; Bouwmeester, H.; Kievid, T.; van Grootveld, G.; Vergragt, P. (Eds.) DTO Sleutel water. In Modellen Van een Duurzame Waterketen; Ten Hagen & Stam B.V.: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sluis, J.W.; Ten Hove, D.; De Boer, B. NWRW Eindrapport. In Eindrapportage en Evaluatie van Het Onderzoek 1982–1989 (NWRW); Ministerie van VROM: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Brugge, R.; Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. The transition in Dutch water management. Reg Env. Change 2005, 5, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wörner, R.; van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Rainproof cities in the Netherlands: Approaches in Dutch water governance to climate-adaptive urban planning. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, E.; Cuppen, E.; Langeveld, J.; de Bruijn, H. De toekomst van het stedelijk watersysteem: Opereren in een stad vol transities. Water Gov. 2019, 3, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, K.; de Vries, E.; Koop, S.; Roest, K. The Energy & Raw Materials Factory: Role and Potential Contribution to the Circular Economy of the Netherlands. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.; Rosemarin, A.; Dickin, S.; Trimmer, C. Sanitation, Wastewater Management and Sustainability: From Waste Disposal to Resource Recovery, 2nd ed.; United Nations Environmental Institute and Stockholm Environmental Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis-Lage, C.L.; Scanlan, P.; deBarbadillo, C.; Barnard, J.; Shaw, A.; Tarallo, S. The Paradigm Shift: Wastewater Plants to Resource Plants; Black & Veatch: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hoek, J.P.; de Fooij, H.; Struker, A. Wastewater as a resource: Strategies to recover resources from Amsterdam’s wastewater. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 113, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaum, C. Wastewater treatment of the future: Health, water and resource protection. In Phosphorus: Polluter and Resource of the Future—Removal and Recovery from Wastewater; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2018; pp. 537–554. [Google Scholar]

- Corvellec, H.; Zapata Campos, M.J.; Zapata, P. Infrastructures, lock-in, and sustainable urban development: The case of waste incineration in the Göteborg Metropolitan Area. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, R. Afkoppelen kost meer dan het aan zuiveringskosten bespaart. Water Gov. 2015, 4, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ampe, K.; Paredis, E.; Asveld, L.; Osseweijer, P.; Block, T. A transition in the Dutch wastewater system? The struggle between discourses and with lock-ins. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 22, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RWS-RIZA. Symposium RWZI 2000: De Stand van Zaken (RWZI-2000 89-08); RWS-RIZA, STORA: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- RWS-RIZA. Evaluatie van Het Onderzoeksprogramma “RWZI 2000” (No. RWZI 2000 95-05); RWS-RIZA, STOWA: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Woude, N. NIDO Programma “Waarden van Water” Afgesloten. H2O 2003, 8, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber, A. Inbreken in het Gangbare. In Transitiemanagement in de Praktijk: De NIDO Benadering; NIDO: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UvW; VNG. Routekaart Afvalwaterketen. In Visiebrochure Afvalwaterketen Tot 2030; Unie van Waterschappen: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber, A.M.C. Practical wisdom in Risk Society. In Methods and Practice of Interpretive Analysis on Questions of Sustainable Development; University of Amsterdam, ISSR: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blankesteijn, M.L. Tussen Wetten en Weten: De Rol van Kennis in Waterbeheer in Transitie; Boom Lemma Uitgevers: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rioned. Riool in Cijfers 2005–2006; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rioned. Riool in Cijfers 2009–2010; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rioned. Riolering in Beeld. In Benchmark Rioleringszorg 2013; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rioned. Het nut van stedelijk waterbeheer. In Monitor Gemeentelijke Watertaken 2016; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rioned. Riool in Cijfers 2002–2003; Stichting Rioned: Ede, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CUWVO. Overstortingen uit Rioolstelsels en Regenwaterlozingen. Aanbevelingen voor het Beleid en de Vergunningverlening. Coördinatiecommissie Uitvoering Wet Verontreiniging Oppervlaktewateren, Werkgroep VI; CUWVO: The Hague, Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stellinga, B. Dertig Jaar Privatisering, Verzelfstandiging en Marktwerking. (No. Nr. 65); WRR Webpublicaties: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Havekes, H.J.M. Verandering en continuïteit in de polder. De institutionele ontwikkeling van het waterschap in de periode 1992–2017. Tijdschr. Voor Waterstaatsgeschied. 2018, 27, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- TK. Brief van de Staatssecretaris van Infrastructuur en Milieu (Tweede Kamer, Vergaderstukken No. 2011–2012, 27625, Nr. 255); Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggen Slaan. Regeerakkoord VVD–PvdA. 2012. Available online: https://groenkennisnet.nl/zoeken/resultaat/bruggen-slaan-:-regeerakkoord-vvd---pvda?id=429999 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Bestuursakkoord Water. Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu, IPO, UvW, VNG, VWM. 2011. Available online: https://open.rijkswaterstaat.nl/@106642/bestuursakkoord-water/ (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- TK. Brief van de Minister van Infrastructuur en Milieu (Tweede Kamer, Vergaderstukken No. 2013–2014, 28, 966, Nr. 27); Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.H. Managing for Value: Organizational Strategy in for-Profit, Nonprofit, and Governmental Organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2000, 29, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TK. Vaststelling van de begrotingsstaat van het Deltafonds voor het jaar 2013. In Brief van de Minister van Infrastructuur en Milieu. (Tweede Kamer, Vergaderstukken No. 2012–2013, 33, 400J, Nr. 19); Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sloover, I.S.; Klootwijk, K. Juridische Handreiking Duurzame Energie en Grondstoffen Waterschappen (STOWA Report No. 2014–40); Berenschot Groep B.V.: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- TK. Vaststelling van de begrotingsstaat van het Deltafonds voor het jaar 2017. In Verslag van een Wetgevingsoverleg. (Tweede Kamer, Vergaderstukken No. 2016–2017, 34, 550J, nr. 24); Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- STOWA & Rioned. s.a. Saniwijzer: Nieuwe Sanitatie in de Praktijk. Available online: https://www.saniwijzer.nl/projecten/nederland/?menu=4&step=0021 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Van Vliet, J. Trans(h)ition? Exploring the Actor-Networks Constituting the Arena for a Transition in Dutch Sanitation. Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University and Researchcenter, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Translating Sustainabilities between Green Niches and Socio-Technical Regimes. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späth, P.; Rohracher, H. Local Demonstrations for Global Transitions—Dynamics across Governance Levels Fostering Socio-Technical Regime Change Towards Sustainability. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Kranz, N. Water governance in times of change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensengerth, O.; Lam, T.H.O.; Tri, V.P.D.; Hutton, C.; Darby, S. How to promote sustainability? The challenge of strategic spatial planning in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2024, 26, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Netherlands 2010. In Value for Money in Government; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, M.; Schillemans, T. De ondefinieerbare staat: Horizontale en verticale sturing door de rijksoverheid sinds 1980. Beleid En Maatsch. 2010, 37, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in Charge here? Governance for Sustainable Development in a Complex World. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. Reflexive modernization as a governance issue–or: Designing and shaping Re-structuration. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Edward Elger: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Netherlands National Emissions Registration Database. Available online: https://www.emissieregistratie.nl/data/overzichtstabellen-water/belasting-naar-oppervlaktewater (accessed on 6 December 2025).

| Vision I. Name: WWTP 2000 Year: 1988–1994 Scope: 2000 | Programme “Future generation sewagewater treatment plant” 1988–1994, by the Ministry of Transport and Water management, RWS-RIZA, and STORA/STOWA. Aim: (i) to develop new treatment techniques that either enhance treatment quality at the same cost or reduce costs while maintaining quality; (ii) to integrate fundamental, long-term scientific research into more empirically focused wastewater treatment research. References: [48,49] |

| Vision II. Name: DTO Water Year: 1993–1997 Scope: 2040 | DTO (Sustainable Technology Development) programme, subprogramme ‘Water’ (1993–1997), by 5 Ministries. Aim: Achieve a sustainable water chain by 2040; reduce environmental pressure per unit of wealth twentyfold, based on LCA. Reduce ‘unsustainabilities’. Reference: [34] |

| Vision III. Name: NIDO Values of water Year: 2000–2003 Scope: not specified | Programme by the National Initiative for Sustainable Development (NIDO). Subprogramme on the water chain. Aim: Stimulate a transition to more sustainable (waste-) water management References: [50,51] |

| Vision IV. Name: Roadmap Wastewater Chain 2030 Year: 2013 Scope: 2030 | Roadmap Wastewater Chain 2030, by UvW and VNG. Aim: To support a sustainable society by valorizing (waste)water and closing cycles. Waste will be (re)turned into resources, energy, and clean water. References: [52] |

| Case 1 Phosphorus removal | Case 2 Separation of stormwater | Case 3 Water cycle companies | Case 4 Energy factory | Case 5 Decentralised sanitation | |

| Scale | Sub-system (WWTP) | Sub-system (sewer) | System (governance) | Sub-system (WWTP) | System |

| Successful? | Yes | Partially | No | Partially? | No |

| Type of change | Incremental | Incremental | Transition | Incremental/Transition | Transition |

| Pressure | Water quality | Water quality Climate change | New Public Management | Climate change | Sustainability |

| Initiative | Top-down | Top-down (temporary) | Bottom-up | Bottom-up | Bottom-up |

| Action by Government | Type of Interaction | Observed in Case |

|---|---|---|

| Create incentives/conditions to improve cooperation between local governments, to overcome the institutionalised task division | Vertical top-down (to achieve lower horizontal) | 2 |

| Prescribe more sustainable measures (technology) by local governments | Vertical top-down | 2 |

| Utilise (material) niches for innovation to experiment with and demonstrate alternatives for the wastewater chain; lending credibility to them | Lower horizontal; vertical bottom-up | 5 |

| Redefine and modify existing infrastructure to connect to new discourses in society | Vertical bottom-up | 4 |

| Contribute to national debate (agenda setting, policy development) by experimenting with new technology and production of knowledge. | Vertical bottom-up | 1 |

| Change the rules by experimenting with innovations outside or at the fringes of the regime (case 4, energy factory); | Vertical bottom-up | 4 |

| Utilise changes in the institutional context to either change or to maintain the institutional status quo. Unintended effect was increased focus on costs | Vertical bottom-up | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

van Dokkum, H.P. How Existing Infrastructure and Governance Arrangement Affect the Development of Sustainable Wastewater Solutions. Sustainability 2026, 18, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010217

van Dokkum HP. How Existing Infrastructure and Governance Arrangement Affect the Development of Sustainable Wastewater Solutions. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010217

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Dokkum, Henno P. 2026. "How Existing Infrastructure and Governance Arrangement Affect the Development of Sustainable Wastewater Solutions" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010217

APA Stylevan Dokkum, H. P. (2026). How Existing Infrastructure and Governance Arrangement Affect the Development of Sustainable Wastewater Solutions. Sustainability, 18(1), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010217