A Case Study on Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Built Environment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, Based on the Adaptive Entropy MGWR Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Information Entropy

2.2.2. Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression Model

2.2.3. Adaptive Information Entropy and MGWR Fusion Method

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Spatial Unit Delineation and Indicator Development

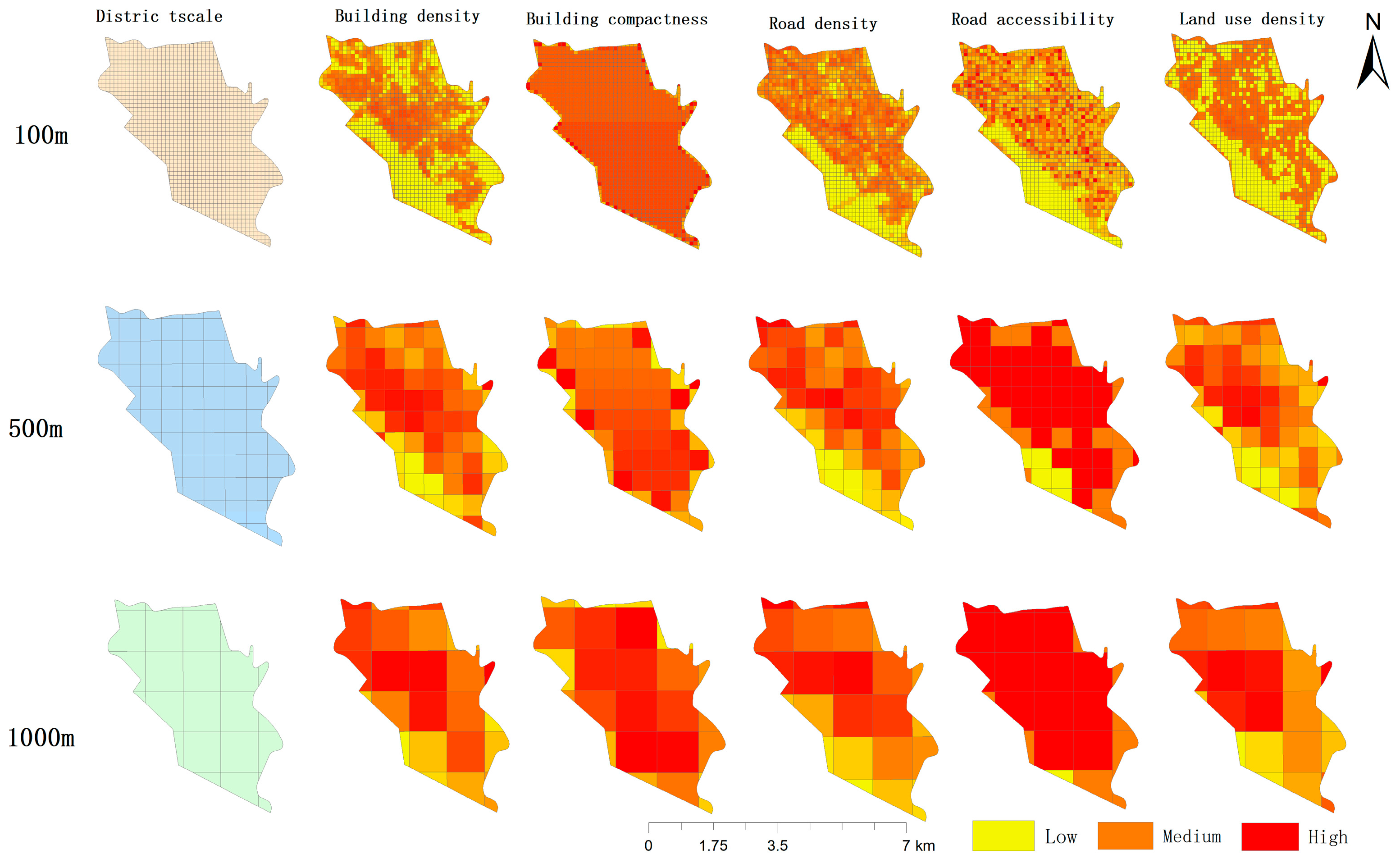

2.4.1. Spatial Unit Division

2.4.2. Indicator Construction

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Multi-Scale Spatial Distribution Characteristics

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Models

3.3. Analysis of Influence Factors at Various Scales

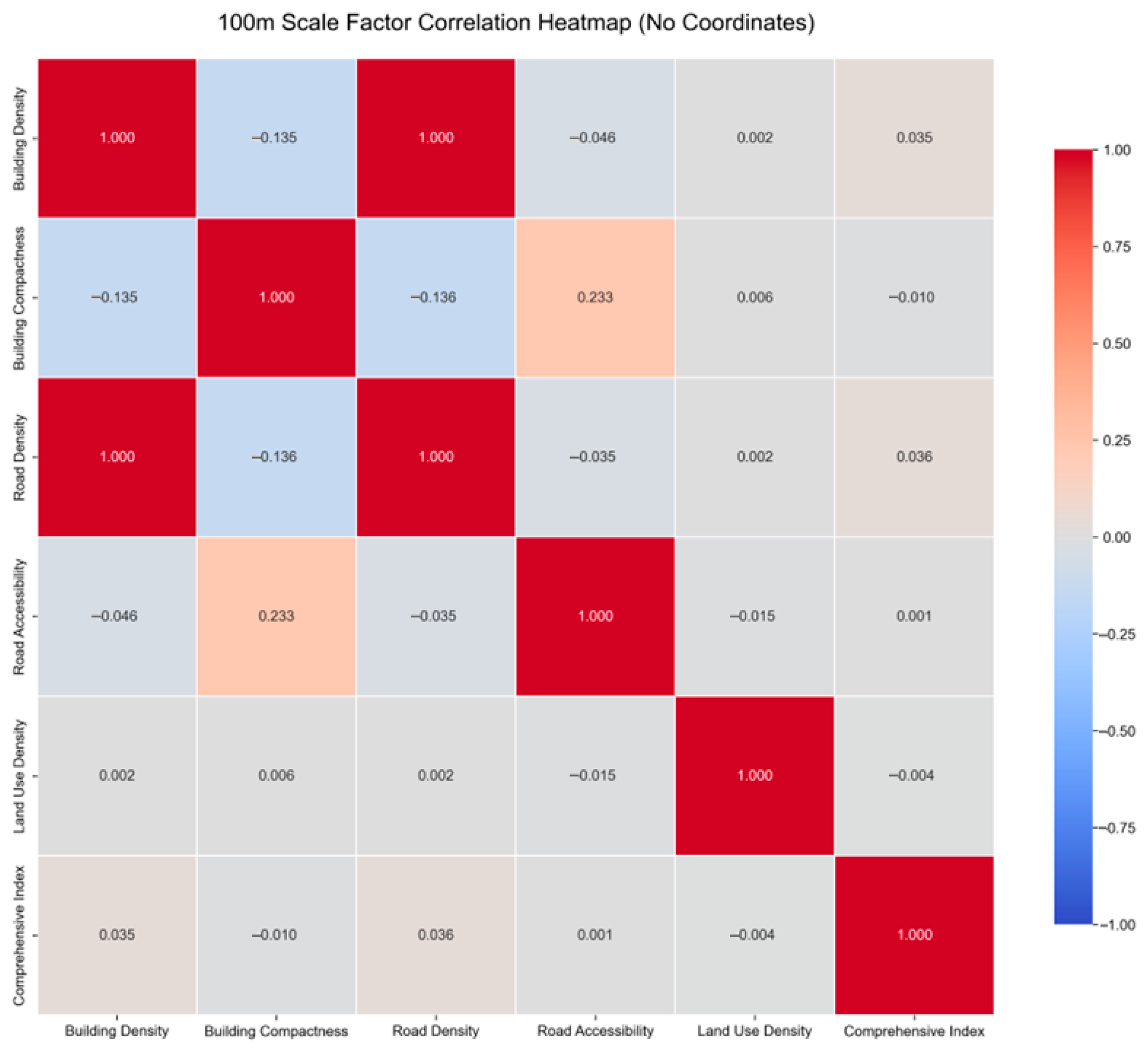

3.3.1. Analysis of MGWR Model Results Based on Adaptive Entropy at the 100 m Scale

3.3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors for the 100 m-Scale GWR Model

3.3.3. Impact Factor Analysis of the MGWR Model Based on Adaptive Entropy at the Scale

3.4. 500 m Scale Influence Factor Analysis

3.4.1. Correlation Analysis of the 500 m Scale Influence Factor

3.4.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors for the 500 m Scale GWR Model

3.5. 1000 m Scale Influence Factor Analysis

3.5.1. Correlation Analysis of the 1000 m Scale Influence Factor

3.5.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors for the 1000 m Scale GWR Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, K.; Helbich, M.; Yang, H. How the built environment shapes our daily journeys: A nonlinear exploration of home and work environments’ relationship with active travel in Shanghai, China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 192, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, D.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, G.; Li, P.; Liu, B.; Gong, P.; Yang, Y. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Land Use and Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Economic Belt of the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Luo, Z. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Factor Misallocation on the Transformation Efficiency of Resource-Based Cities Based on the Optimization Direction Function Calculation Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Emissions trading scheme and energy consumption and output structure: Evidence from China. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbusch, N.T.; Saunders, M.D.; Leonard, K.; St-Hilaire, A.; Gibson, R.B.; Jardine, T.D.; Courtenay, S.C. A systematic scoping review of the collaborative governance of environmental and cultural flows. Environ. Rev. 2025, 33, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty-Gastaldi, J.; Sabourault, C.; Lazaric, N.; Dérijard, B. Urban typology of marine protected areas (MPAs): An exploratory methodological framework applied to the Western Mediterranean Sea. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, Q. Uncovering Drivers of Resident Satisfaction in Urban Renewal: Contextual Perception Mining of Old Community Regeneration Through Large Language Models. Buildings 2025, 15, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.T.; Ullah, S.; Ozturk, I.; Sohail, S. Energy justice, digital infrastructure, and sustainable development: A global analysis. Energy 2025, 319, 134999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dong, Z.; Shi, R.; Sun, G.; Guo, Y.; Peng, Z.; Deng, M.; Chen, K. Urban Multi-Scenario Land Use Optimization Simulation Considering Local Climate Zones. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodníková, V.; Hamerlík, L.; Trnková, K.; Wojewódka-Przybył, M.; Chamutiová, T.; Szarlowicz, K.; Korponai, J.; Auxtová, M.; Turis, P.; Bitušík, P. Reconstructing limnological and vegetation changes in the Eastern Carpathians (Ukraine) over the past 200 years inferred from sediments of three contrasting alpine lakes. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucała-Hrabia, A. Reflections on land use and land cover change under different socio-economic regimes in the Polish Western Carpathians. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, H.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.; Zheng, K.; Dong, T.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Characteristics of Changes in Land Use Intensity in Xinjiang Under Different Future Climate Change Scenarios. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, P. Assessing the photovoltaic application potential of non-building areas in existing high-density residential areas. Build. Environ. 2025, 283, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Evaluation Methods and Optimization Strategies for Low-Carbon-Oriented Urban Road Network Structures: A Case Study of Shanghai. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, R. A matter of size: Comparing IV and OLS estimates. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0334392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orak, N.H.; Smail, L. A Bayesian Network model to integrate blue-green and gray infrastructure systems for different urban conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A.; Pollet, B.G. Empowering Australia’s hydrogen economy: A local approach to sustainable technology and independence. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 98, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, S.; Ramadan, B.S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Munawir, M.; Khair, H.; Rosmalina, R.T.; Ardiansyah, S.Y. Analysis of Factors Influencing Illegal Waste Dumping Generation Using GIS Spatial Regression Methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xu, J.; Natarajan, B.Y.; Mostafavi, A. Interpretable machine learning learns complex interactions of urban features to understand socio-economic inequality. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 2013–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Dai, X.; Wu, Y.; Kang, N.; Zhang, T.; Gou, J.; Tao, Y. Driving forces of agricultural ammonia emissions in semi-arid areas of China: A spatial econometric approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Srinivasan, K.K. Geographically Weighted Nonlinear Regression for Cost-Effective Policies to Enhance Bus Ridership. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Rao, C.; Xiao, X.; Hu, F.; Goh, M. Interactive geographical and temporal weighted regression to explore spatio-temporal characteristics and drivers of carbon emissions. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Air Quality and Its Driving Factors in Beijing’s Main Urban Area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, G.; Barrand, N.E.; Geng, H.; An, J.; Su, Y. Improving the Spatial Resolution of GRACE-Derived Ice Sheet Mass Change in Antarctica. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4300112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cai, H.; Duan, H.; Du, Y.; Chen, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Yeh, H.-C. A Novel Approach to Scale Factor Determination with Carrier-Sideband Correlation for Inter-Satellite Laser Interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5652708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yang, W.; Hu, J.; Wu, K.; Li, H. Exploring the nexus between rural economic digitalization and agricultural carbon emissions: A multi-scale analysis across 1607 counties in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dai, P. Research on Spatial Differentiation of Housing Prices Along the Rail Transit Lines in Qingdao City Based on Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Tong, Z.; An, R. A Study on the Nonlinear Relationship between Urban Vitality and the Built Environment Based on Multi-source Data: The Case of Wuhan’s Main Urban Area on Weekends. Adv. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 42, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lei, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity in the Impact of the Built Environment on Urban Vitality: A Big Data Analysis. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 42, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jiang, Y. Spatial Heterogeneity in the Impact of the Built Environment on Urban Vitality: A Case Study of Nanjing’s Central Urban Area. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 1700–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Meng, Y.; Li, W.; Guo, Y. Study on the Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Motor Vehicle Travel Influenced by the Built Environment. J. Transp. Eng. Inform. 2024, 22, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Kim, H. COVID-19 and urban vitality: The association between built environment elements and changes in local points of interest using social media data in South Korea. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 123, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niero, A.; Brenes-Peralta, L.; Pölling, B.; Vittuari, M. Exploring social handprints on well-being: A methodological framework to assess the contribution of business models in city region food systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, W. Geographically Aware Air Quality Prediction Through CNN-LSTM-KAN Hybrid Modeling with Climatic and Topographic Differentiation. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Nam, K.-M. Impacts of local and regional carbon markets in Hong Kong and China’s Greater Bay Area: A dynamic CGE analysis. Energy Policy 2025, 204, 114651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Oppio, A.; Bonardo, M.; Quaglia, G. Hybrid evaluation approaches for urban regeneration processes of landfills and industrial sites: The case of the Kwun Tong area in Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesthrige, J.W.; Wong, J.K.W.; Yuk, L.N. Conversion or redevelopment? Effects of revitalization of old industrial buildings on property values. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qu, L.; Zhang, G.; Xie, N. Attribute selection for heterogeneous data based on information entropy. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 2021, 50, 548–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Bi, L.; Dai, S. Information Distances versus Entropy Metric. Entropy 2017, 19, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; He, R. Refined Urban Functional Zone Mapping by Integrating Open-Source Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ming, D.; Lv, X.; Zhou, K.; Bao, H.; Hong, Z. SO–CNN based urban functional zone fine division with VHR remote sensing image. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.K.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Bennett, E.L.; Boyle, M.J.W.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Money, D.; Prohaska, A.; Young, R.; Young, R.; et al. The Impact of Spatial Delineation on the Assessment of Species Recovery Outcomes. Diversity 2022, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaxing, L.; Bojie, Y.; Jingjie, Y. Correlation between Road Network Accessibility and Urban Land Use: A Case Study of Fuzhou City. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 2915–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Guo, T.; Wang, D. Dynamic Accessibility Analysis of Urban Road-to-Freeway Interchanges Based on Navigation Map Paths. Sustainability 2021, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Type | Indicator Name | Calculation Formula | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological | Building Density | Building Density = (Floor Area of Building Basements/Total Construction Land Area) × 100% | Measures the intensity of urban spatial development and reflects the degree of building coverage per unit area |

| Building Compactness | Building Compactness = Building Floor Area/Building Perimeter | Characterizes the regularity of building form and the efficiency of space utilization | |

| Structural | Road Density | Road Density = Total Length of All Roads/Total Regional Area | Measures the development level of the road network |

| Road Accessibility | d = s/(2L) (where d = influence distance, s = built-up area, L = total length of primary and secondary trunk roads) | Evaluates the connectivity of the road network and travel efficiency | |

| Functional | Land Use Density | La = Σ(Ai × Ci) (where La = comprehensive index of land use intensity; Ai = classification index of land use intensity at level i; Ci = percentage of area classified by land use intensity at level i) | Reflects the intensity of land use and embodies the overall development level of land use types |

| Comprehensive | Comprehensive Built Environment Index | Comprehensive Built Environment Index = Σ(wi × Xi) (where wi = weight of the i-th indicator, Σwi = 1; Xi = standardized value of the i-th indicator) | Reflects the different contributions of each indicator to the comprehensive level of the built environment and realizes the weighted integration of multiple indicators |

| Model | R2 | Adjusted R2 | AIC/AICc | RMSE | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | 0.402 | 0.308 | 1958.402 | 0.230 | 1000 m |

| GWR | 0.793 | 0.754 | 1957.947 | 0.229 | 500 m |

| MGWR based on Adaptive Entropy | 0.893 | 0.8251 | 1956.568 | 0.216 | 100 m |

| Indicator Name | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum Regression Coefficient | Maximum Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Density | 0.000151 | 0.15769 | 0.003131 | 0.00000 | 0.11576 |

| Building Compactness | 0.276918 | 0.28771 | 0.035567 | 0.00000 | 0.30165 |

| Road Density | 0.000298 | 0.00068 | 0.004618 | 0.00000 | 0.17077 |

| Road Accessibility | 0.074377 | 0.05722 | 0.058879 | 0.00000 | 0.286127 |

| Land Use Density | 0.000179 | 0.000031 | 0.003395 | 0.000013 | 0.125670 |

| Indicator Name | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum Regression Coefficient | Maximum Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Density | 0.008506 | 0.042229 | 0.002221 | 0.00000 | 0.362397 |

| Building Compactness | 0.223106 | 0.137179 | 0.241403 | 0.00000 | 0.643982 |

| Road Density | 0.019559 | 0.038188 | 0.012500 | 0.00000 | 0.314028 |

| Road Accessibility | 0.133332 | 0.070558 | 0.134891 | 0.00000 | 0.263861 |

| Land Use Density | 0.005032 | 0.033247 | 0.000525 | 0.00000 | 0.286677 |

| Indicator Name | Correlation Coefficient | Regression Coefficient | Impact Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Density | 0.3924 | 0.2599 | Positive Impact |

| Building Compactness | 0.3080 | −0.2593 | Negative Impact |

| Road Density | 0.2364 | 0.1011 | Positive Impact |

| Road Accessibility | 0.1706 | 0.1814 | Positive Impact |

| Land Use Density | 0.2164 | 0.1950 | Positive Impact |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, X.; Huo, L.; Shen, T.; Kong, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. A Case Study on Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Built Environment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, Based on the Adaptive Entropy MGWR Model. Sustainability 2026, 18, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010189

Wei X, Huo L, Shen T, Kong F, Liu Z, Wu J. A Case Study on Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Built Environment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, Based on the Adaptive Entropy MGWR Model. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010189

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Xuejia, Liang Huo, Tao Shen, Fulu Kong, Zhaoyang Liu, and Jia Wu. 2026. "A Case Study on Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Built Environment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, Based on the Adaptive Entropy MGWR Model" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010189

APA StyleWei, X., Huo, L., Shen, T., Kong, F., Liu, Z., & Wu, J. (2026). A Case Study on Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Built Environment in Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, Based on the Adaptive Entropy MGWR Model. Sustainability, 18(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010189