Experimental Study on Cycle Aging Life of 21700 Cylindrical Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Equipment

- NEWARE CT4008-5V12A battery charging (NEWARE Technology LLC, Shenzhen, China) and discharging equipment was used to control the battery operation according to the test process mentioned below. Battery charging and discharging equipment can record the terminal voltage, current and other electrical data of the operating battery.

- An ESPEC GPU-3 (ESPEC Corp., Osaka, Japan) environmental chamber with an internal integrated heating and cooling system was used to create an adjustable constant-temperature environment for battery testing.

- An OMEGA high-precision T-type thermocouple (OMEGA Engineering, Norwalk, CT, USA) was connected to a National Instruments 9214 board and cRIO-9037 board (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) base to form a temperature acquisition system. The thermocouples were calibrated in an oil bath using a first-class standard mercury thermometer.

2.2. Self-Made Temperature Control Devices for Cylindrical Battery

2.2.1. Side Face Temperature Control Device for the Cylindrical Battery

2.2.2. End Faces Temperature Control Device for the Cylindrical Battery

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Temperature Measurement

2.3.2. Charge and Discharge Tests

2.3.3. Nominal Capacity Test

2.3.4. Direct Current (DC) Internal Resistance Test

2.3.5. Quasi-Open Circuit Voltage (OCV) Test

2.3.6. Cycle Aging Test

3. Results and Discussion

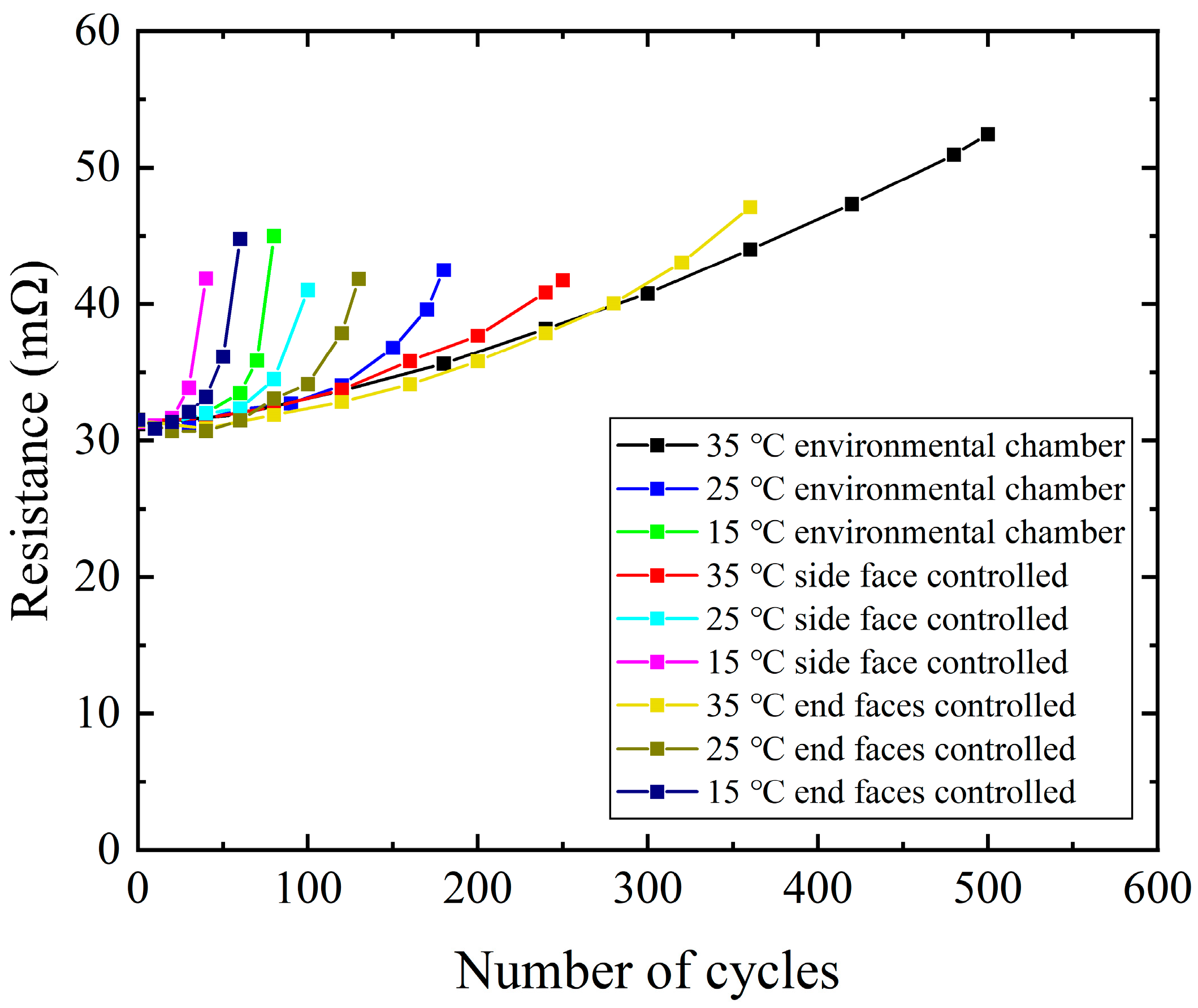

3.1. Aging Results of Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions

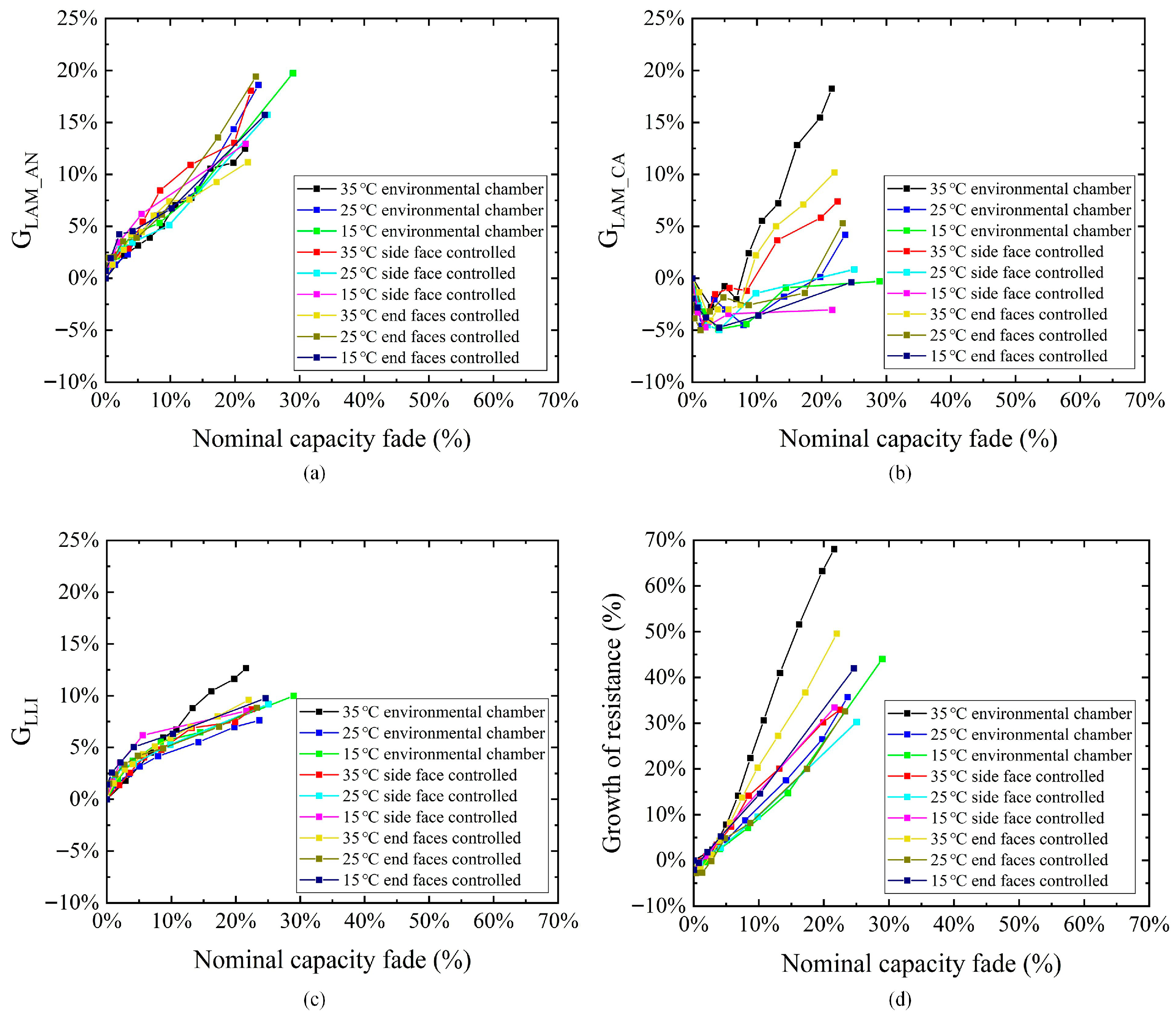

3.2. Analysis of Battery Aging Mechanism

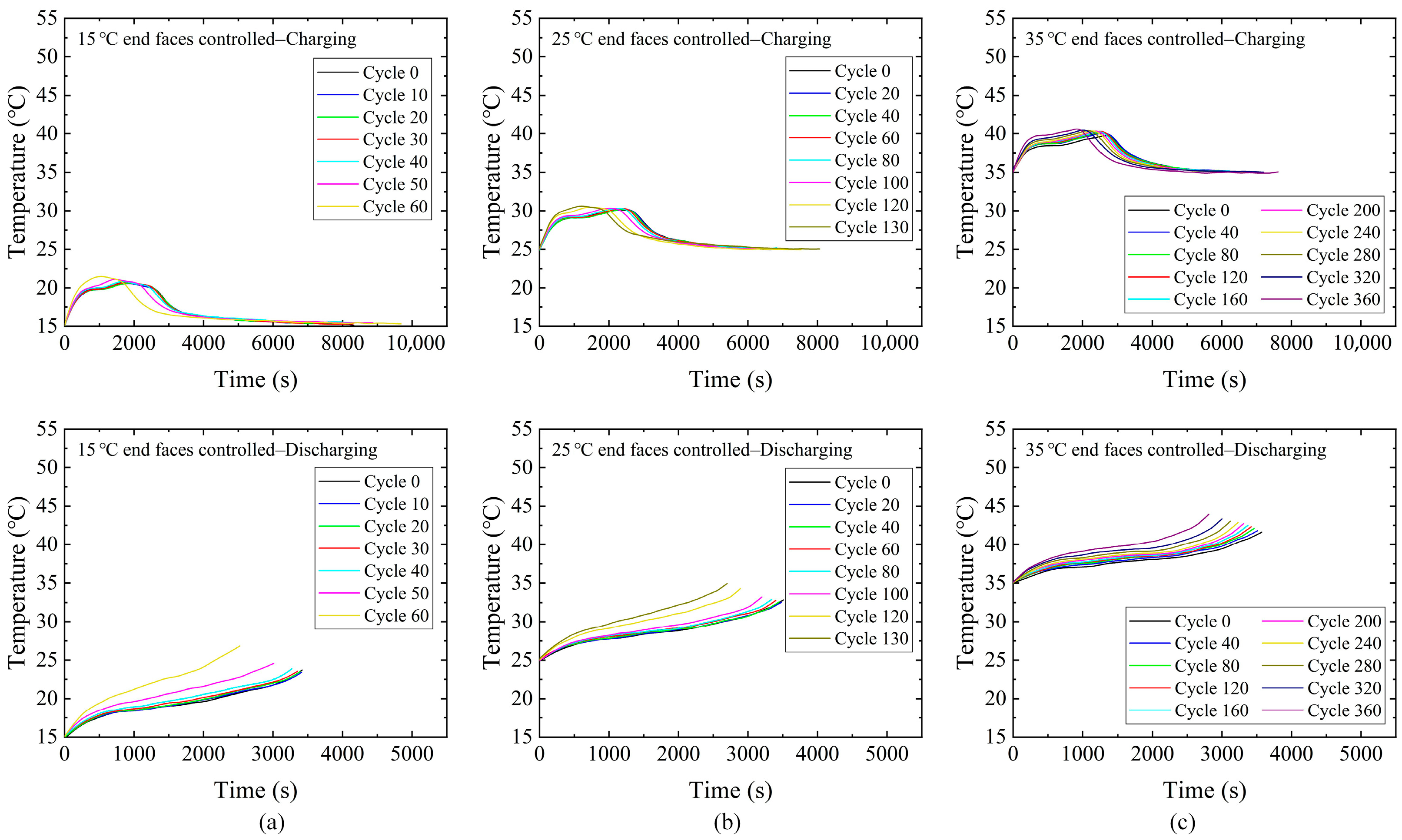

3.3. Temperature Results of Batteries During Cycle Aging Process

3.4. Correlation Between Battery Temperature and Nominal Capacity Fade

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Key Results

- The maximum loss rate of active anode material is close to 20% after the battery aging tests, with an obvious correlation with the nominal capacity fade. Meanwhile the correlation between the active cathode material loss and the capacity degradation is insignificant.

- The loss rate of lithium inventory of most test groups is approximately 10% after the battery aging tests, which directly impacts the reduction in the battery’s nominal capacity. The internal resistance growth rate can exceed 50% at the end of the battery’s life.

- Experimental data of the 21700 cylindrical batteries show that the lower the CTAT, the fewer the number of available cycles within the temperature range of this study.

- A semi-empirical battery aging model was established that describes the correlation between the fade percentage of battery nominal capacity and the CTAT, as well as the number of cycles.

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTAT | Cumulative time-averaged surface temperature |

| LFP | Lithium iron phosphate |

| NCM | Nickel cobalt manganese |

| NCA | Nickel cobalt aluminum |

| TEC | Thermoelectric cooler |

| PID | Proportional–integral–derivative |

| NTC | Negative temperature coefficient |

| CC | Constant current |

| CV | Constant voltage |

| DC | Direct current |

| HPPC | Hybrid pulse power characterization |

| SOC | State of charge |

| OCV | Open circuit voltage |

| DV | Differential voltage |

| LAM | Loss of active electrode material |

| LLI | Loss of lithium inventory |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interface |

References

- Deng, J.; Bae, C.; Denlinger, A.; Miller, T. Electric Vehicles Batteries: Requirements and Challenges. Joule 2020, 4, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ling, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Delayed liquid cooling strategy with phase change material to achieve high temperature uniformity of Li-ion battery under high-rate discharge. J. Power Sources 2020, 450, 227673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offer, G.; Patel, Y.; Hales, A.; Bravo, D.L.; Marzook, M. Cool metric for lithium-ion batteries could spur progress. Nature 2020, 582, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Huang, R.; Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Qian, K.; Bhagat, R. Air and PCM cooling for battery thermal management considering battery cycle life. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 173, 115154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Yu, X. Simulation Study on Heat Generation Characteristics of Lithium-Ion Battery Aging Process. Electronics 2023, 12, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Munk-Nielsen, S.; Knap, V.; Uhrenfeldt, C. Performance evaluation of lithium-ion batteries (LiFePO4 cathode) from novel perspectives using a new figure of merit, temperature distribution analysis, and cell package analysis. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, E.; Efimova, S.; Colalongo, M.; Kauranen, P.; Lahtinen, K.; Napolitano, E.; Ruiz, V.; Moškon, J.; Gaberšček, M.; Park, J.; et al. Aging mechanisms of NMC811/Si-Graphite Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 599, 234159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, P.; Opitz, A.; Shen, L.; Vaidya, R.; Mayyas, A.; Knoop, K.; Razdan, A.; Kannan, A.M. Performance of 26650 Li-ion cells at elevated temperature under simulated PHEV drive cycles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12396–12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkaldy, N.; Samieian, M.A.; Offer, G.J.; Marinescu, M.; Patel, Y. Lithium-ion battery degradation: Comprehensive cycle ageing data and analysis for commercial 21700 cells. J. Power Sources 2024, 603, 234185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucinskis, G.; Bozorgchenani, M.; Feinauer, M.; Kasper, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Waldmann, T. Arrhenius plots for Li-ion battery ageing as a function of temperature, C-rate, and ageing state—An experimental study. J. Power Sources 2022, 549, 232129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Xie, H.; Yang, X.; Niu, W.; Li, S.; Chen, S. The Dilemma of C-Rate and Cycle Life for Lithium-Ion Batteries under Low Temperature Fast Charging. Batteries 2022, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Keil, P.; Schuster, S.F.; Jossen, A. Impact of Temperature and Discharge Rate on the Aging of a LiCoO2/LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 Lithium-Ion Pouch Cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A1438–A1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinauer, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Hölzle, M.; Waldmann, T. Temperature-driven path dependence in Li-ion battery cyclic aging. J. Power Sources 2024, 594, 233948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalstieg, J.; Käbitz, S.; Ecker, M.; Sauer, D.U. A holistic aging model for Li(NiMnCo)O2 based 18650 lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 257, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, X.; Ji, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y. Research progress on power battery cooling technology for electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khange, S.; Sharma, A.K. Elucidating effects of form factors on thermal and aging behavior of cylindrical lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210, 109564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. Specification of Product INR21700-50E, SAMSUNG SDI. 2019. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/494734630/INR21700-50E (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Yu, X.; Wu, Q.; Huang, R.; Chen, X. A Novel Heat Generation Acquisition Method of Cylindrical Battery Based on Core and Surface Temperature Measurements. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2022, 19, 030905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Huang, R.; Yu, X. Measurement of thermophysical parameters and thermal modeling of 21700 cylindrical battery. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 36276-2023; Lithium-Ion Battery for Electrical Energy Storage. China Electricity Council: Beijing, China, 2023.

- INEEL. FreedomCAR Battery Test Manual for Power-Assist Hybrid Electric Vehicles; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Feng, X.; Merla, Y.; Weng, C.; Ouyang, M.; He, X.; Liaw, B.Y.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Lu, L.; et al. A reliable approach of differentiating discrete sampled-data for battery diagnosis. eTransportation 2020, 3, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, M.; Torcheux, L.; Kobayashi, Y. Knee point prediction for lithium-ion batteries using differential voltage analysis and degree of inhomogeneity. J. Power Sources 2024, 621, 235210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, P.; Jossen, A. Calendar Aging of NCA Lithium-Ion Batteries Investigated by Differential Voltage Analysis and Coulomb Tracking. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A6066–A6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Fernández, C.; Uddin, K.; Chouchelamane, G.H.; Widanage, W.D.; Marco, J. A Comparison between Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Incremental Capacity-Differential Voltage as Li-ion Diagnostic Techniques to Identify and Quantify the Effects of Degradation Modes within Battery Management Systems. J. Power Sources 2017, 360, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; He, R.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, S. Aging mechanisms of cylindrical NCA/Si-graphite battery with high specific energy under dynamic driving cycles. J. Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, H.; Zhang, N.; Jahn, M.; Arrinda, M.; Ritz, S.; Faber, M.; Sauer, D.U.; Azais, P.; Cendoya, I. Ante-mortem analysis, electrical, thermal, and ageing testing of state-of-the-art cylindrical lithium-ion cells. E I Elektrotech. Inf. 2020, 137, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Kopljar, D.; Friedrich, K.A. Detailed investigation of degradation modes and mechanisms of a cylindrical high-energy Li-ion cell cycled at different temperatures. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, J.; Rheinfeld, A.; Zilberman, I.; Spingler, F.B.; Kosch, S.; Frie, F.; Jossen, A. Modeling and simulation of inhomogeneities in a 18650 nickel-rich, silicon-graphite lithium-ion cell during fast charging. J. Power Sources 2019, 412, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.R.; Smith, A.J.; Frenander, K.; Mikheenkova, A.; Lindström, R.W.; Thiringer, T. Influence of state of charge window on the degradation of Tesla lithium-ion battery cells. J. Energy Storage 2024, 76, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhala, T.; Jalkanen, K.; Romann, T.; Lust, E.; Omar, N.; Kallio, T. Low-temperature aging mechanisms of commercial graphite/LiFePO4 cells cycled with a simulated electric vehicle load profile—A post-mortem study. J. Energy Storage 2018, 20, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Chen, G.; Tian, J.; Li, N.; Chen, L.; Su, Y.; Song, T.; Lu, Y.; Cao, D.; Chen, S.; et al. Unrevealing the effects of low temperature on cycling life of 21700-type cylindrical Li-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 60, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Xu, B.; Cui, Y.; Feng, X.; Han, X.; Zheng, Y. A sequential capacity estimation for the lithium-ion batteries combining incremental capacity curve and discrete Arrhenius fading model. J. Power Sources 2021, 484, 229248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Model | Nominal Capacity (Ah) | Charging Cut-off Voltage (V) | Discharging Cut-off Voltage (V) | Height (mm) | Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMSUNG INR21700-N50E (Samsung SDI Co., Ltd., Yongin, Republic of Korea) | 4.9 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 70 | 21 |

| Equipment | Model | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Battery charging and discharging equipment | Neware CT4008-5V12A | Voltage range: 25 mV–5 V; current range: 5 mA–12 A; accuracy: ±0.05% |

| Environmental chamber | ESPEC GPU-3 | Temperature range: −40 °C–150 °C; temperature fluctuation ≤ ±0.3 °C |

| Thermocouple | OMEGA T-type | Diameter: 0.6 mm; range: −267 °C~260 °C |

| Temperature acquisition board | NI 9214 | Number of channels: 16; errors: 0.33 °C |

| Temperature board base | NI cRIO-9037 | 1.33 GHz dual-core Intel Atom processor |

| Component | Parameters |

|---|---|

| 12706 TEC (Tianqi Star Electronics Co., Shenzhen, China) | Voltage: 12 V; size: 40 mm × 40 mm × 4 mm |

| TCM-M207 TEC controller (TE Technology, Traverse City, MI, USA) | Voltage: 24 V; maximum current: 7 A |

| Thin-film NTC thermistor | Probe thickness: 0.5 mm; measurement error: 0.35 °C |

| Fan | Voltage: 24 V; size: 60 mm × 60 mm × 25 mm |

| Copper fin | Size: 60 mm × 60 mm × 22 mm |

| Thermal conductive silicone pad | Thickness: 1 mm; thermal conductivity: 6.5 W/(m·K) |

| Power supply | Voltage: 24 V; maximum current: 15 A |

| Step | Time (s) | Rate (C) | Current (A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant-current discharge | 10 | 1 | 4.9 |

| Shelve | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Constant-current charge | 10 | 0.75 | 3.675 |

| Heat Exchange Condition | CTAT (°C) | Number of Available Cycles |

|---|---|---|

| 15 °C environmental chamber | 20.5 | 75 |

| 25 °C environmental chamber | 30.4 | 172 |

| 35 °C environmental chamber | 40.3 | 495 |

| 15 °C side face controlled | 15.0 | 40 |

| 25 °C side face controlled | 25.0 | 97 |

| 35 °C side face controlled | 35.0 | 243 |

| 15 °C end faces controlled | 17.8 | 58 |

| 25 °C end faces controlled | 27.7 | 125 |

| 35 °C end faces controlled | 37.7 | 348 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, Q.; Li, Z.; Gan, Y.; Wan, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, X. Experimental Study on Cycle Aging Life of 21700 Cylindrical Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions. Sustainability 2026, 18, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010187

Wu Q, Li Z, Gan Y, Wan Z, Jiang Q, Yu X. Experimental Study on Cycle Aging Life of 21700 Cylindrical Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Qichao, Zhi Li, Yijie Gan, Zhifang Wan, Quanying Jiang, and Xiaoli Yu. 2026. "Experimental Study on Cycle Aging Life of 21700 Cylindrical Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010187

APA StyleWu, Q., Li, Z., Gan, Y., Wan, Z., Jiang, Q., & Yu, X. (2026). Experimental Study on Cycle Aging Life of 21700 Cylindrical Batteries Under Different Heat Exchange Conditions. Sustainability, 18(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010187