1. Introduction

China’s economic transformation since the 1980s presents a remarkable case study in institutional coexistence. State-Owned Enterprises and Non-State-Owned Enterprises have operated side by side for forty years, creating what scholars call a “dual-track” system. This arrangement has left deep imprints on how China developed. SOEs inherited their position as the economy’s traditional backbone, while NSOEs emerged as drivers of growth and innovation. These two enterprise forms do not merely differ in ownership structure—they respond to entirely different institutional logics and pursue divergent strategic objectives. Researchers have devoted considerable attention to comparing these groups, examining their efficiency, governance structures, and financial outcomes. The prevailing consensus in this literature holds that NSOEs surpass SOEs when measured by market-oriented indicators like profitability, productivity, and how efficiently they turn over assets.

The landscape has shifted considerably as China pursues what the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) terms “high-quality development.” This policy orientation renders traditional financial metrics inadequate for evaluating firm performance. Sustainable development now occupies center stage in both Chinese national policy and global frameworks like the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This shift necessitates broader criteria for assessing firm value—criteria extending well beyond economic efficiency to encompass innovation capability, social responsibility, and alignment with cultural values. Such multidimensional thinking matters especially in China’s institutional environment. SOEs face explicit mandates that have little to do with financial returns. They must maintain employment levels even when doing so hurts efficiency. They undertake strategic projects in underdeveloped regions where market logic would discourage investment. They shoulder responsibilities for national economic security and must act as stabilizing forces during economic turbulence. These non-financial obligations define much of what SOEs actually do.

Despite the importance of this topic, the existing literature reveals several critical gaps that this study aims to address. First, most comparative studies of SOEs versus NSOEs remain fixated on financial performance indicators, systematically underrepresenting intangible value dimensions such as innovation output, social legitimacy, stakeholder engagement, and cultural continuity. Second, few studies have systematically operationalized and measured the social and cultural contributions of SOEs versus NSOEs using objective, quantifiable metrics that enable rigorous cross-group comparison. Third, the spatial dimension of this divergence remains severely under-theorized. While NSOEs are known to cluster based on market efficiency principles and agglomeration economies as predicted by new economic geography, the spatial logic of SOE value—which may be fundamentally tied to policy directives and national strategic layout rather than market forces—is far less understood in the empirical literature.

To address these shortcomings, this study develops a comprehensive four-dimensional value-assessment framework encompassing economic, innovation, social, and cultural dimensions. This framework is applied comparatively to a rigorously constructed balanced panel of 3025 A-share listed firms, systematically classified into 1, 120 SOEs and 1905 NSOEs, spanning the period from 2014 to 2023. We employ the entropy weighting method—an objective, data-driven approach that assigns weights based on indicator variability—to construct composite value indices for each group separately, thereby revealing differences not only in value levels but also in the structural composition of value. Building upon this foundation, we utilize an integrated suite of spatial statistical tools, including spatial heat maps, Dagum Gini coefficient decomposition, Theil indices, and coefficients of variation, to systematically map the evolution and regional disparities in firm value over the decade-long observation period.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

- (1)

How does the multidimensional value structure of SOEs differ fundamentally from that of NSOEs in terms of both absolute levels and relative composition across the four dimensions?

- (2)

What are the temporal evolution trends for each of the four value dimensions within each group, and how have these trajectories diverged or converged over the 2014–2023 period?

- (3)

What spatial patterns and regional disparities characterize the distribution of SOE and NSOE value across China’s provinces and macro-regions, and how have these spatial configurations evolved over time?

- (4)

What firm-level and regional-level factors systematically explain variations in composite value within and between the two groups?

By offering a theoretically grounded and empirically robust framework for understanding the spatial and multidimensional evolution of firm value in China’s dual-track system, this study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, it advances the conceptual integration of multiple value dimensions—moving beyond the traditional dichotomy of financial versus non-financial performance to specify distinct domains of sustainable value creation. Second, it provides novel empirical evidence on the systematic differences in value drivers between SOEs and NSOEs using objective weighting methods. Third, it highlights the structural drivers of regional inequality in firm value and demonstrates how institutional heterogeneity shapes divergent development paths. Finally, it offers actionable insights for policymakers seeking to design differentiated incentive structures that leverage the unique strengths of both SOEs and NSOEs to foster a more balanced, inclusive, and sustainable national economy.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypotheses

2.1. Paradigm Evolution in Comparative Enterprise Research

Research on the comparative performance of SOEs and NSOEs has undergone significant paradigmatic evolution over the past three decades. Early studies, predominantly influenced by neoclassical economics and agency theory, focused almost exclusively on efficiency differentials and governance mechanisms. These studies typically found that NSOEs outperformed SOEs on traditional financial metrics, attributing the gap to softer budget constraints, political interference, and weaker managerial incentives in state-controlled firms [

1]. However, this narrow performance-centric approach was soon challenged for its inability to capture the distinctive non-market roles, strategic mandates, and institutional embeddedness of SOEs, particularly in transition and emerging economies.

In response to these limitations, scholars began adopting more nuanced theoretical perspectives. The resource-based view (RBV), originally developed to explain sustained competitive advantage in private firms, was extended to analyze how SOEs and NSOEs differ in their access to and deployment of strategic resources. SOEs typically enjoy preferential access to critical production factors such as capital (through state-owned banks), land (through administrative allocation), and licenses (through regulatory favoritism). However, they simultaneously face resource constraints in terms of managerial talent (due to bureaucratic pay scales) and market-oriented innovation capabilities (due to risk-averse governance cultures). NSOEs, conversely, must generate their own competitive advantages primarily through agility, entrepreneurial innovation, and efficient resource recombination in competitive markets [

2].

2.2. A Multidimensional Framework for Firm Value

Building upon these diverse theoretical traditions, this study proposes an integrated four-dimensional framework for evaluating firm value that explicitly recognizes the multifaceted nature of sustainable development. Each dimension captures a distinct but interconnected aspect of long-term value creation:

This dimension captures traditional financial performance and operational efficiency metrics, including profitability (ROA, ROE), growth rates (revenue growth), market valuation (Tobin’s Q), and capital structure (leverage ratios). It reflects the firm’s fundamental ability to generate stable returns, allocate resources effectively, and maintain financial sustainability—objectives that are theoretically shared by both SOEs and NSOEs, though the performance benchmarks and accountability mechanisms differ substantially.

This dimension reflects the firm’s capacity for technological development, knowledge accumulation, and adaptive capability in dynamic environments. Metrics include R&D investment intensity, patent applications and grants, R&D personnel headcount, and technology-intensive revenue shares. Innovation is increasingly recognized as a critical driver of long-term competitiveness and a central pillar of China’s national development strategy, as articulated in policies such as ‘Made in China 2025’ and the 14th Five-Year Plan. For NSOEs, innovation represents a survival imperative in competitive markets; for SOEs, it constitutes a policy mandate embedded in state directives for technological self-reliance.

This dimension refers to a firm’s contribution to stakeholder well-being, employment stability, community engagement, and fulfillment of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Indicators include employment growth rates, CSR disclosure quality and keyword frequency (e.g., ‘poverty alleviation,’ ‘charitable donation,’ ‘employee welfare’), environmental compliance, and stakeholder satisfaction. This dimension is particularly salient for SOEs, which explicitly bear ‘social burdens’ as instruments of state policy—including maintaining excess employment during economic downturns, investing in economically marginal regions for social stability purposes, and providing public goods that private firms would under-supply.

This dimension represents the firm’s role in promoting organizational identity, aligning with broader value systems, and preserving institutional memory across time. For NSOEs, particularly family-controlled firms, this may relate to founder philosophy, entrepreneurial spirit, and clan-based governance cultures. For SOEs, cultural value strongly connects to alignment with national ideology, policy narratives, and socialist corporate citizenship. Measurement proxies include keyword frequency in annual reports for terms such as ‘Party building,’ ‘national strategy,’ ‘political consciousness,’ ‘founder legacy,’ and ‘corporate spirit.’ Though difficult to quantify, cultural value is theoretically indispensable for understanding long-term resilience and intergenerational continuity.

2.3. Institutional Logics and Hypotheses Development

The primary theoretical lens for comparing SOEs and NSOEs is Institutional Theory, which posits that organizations are embedded in institutional fields characterized by distinct regulatory structures, normative expectations, and cognitive frameworks [

3,

4]. SOEs and NSOEs are embedded in fundamentally different institutional environments and respond to different—and at times contradictory—sets of institutional pressures.

NSOEs, particularly private and family-controlled firms, operate primarily under a ‘market logic.’ Their survival and success are contingent on market competition, operational efficiency, and profitability. While they may engage in social activities such as philanthropy or environmental initiatives, these are often secondary to or instrumental for achieving primary economic goals (e.g., reputation enhancement, regulatory compliance). The Resource-Based View (RBV) suggests that NSOEs must generate their own competitive advantages, primarily through agility, innovation, and entrepreneurial risk-taking, to secure resources in a competitive environment where capital, talent, and market access are allocated based on performance rather than political connections.

H1. Non-State-Owned Enterprises (NSOEs) will exhibit significantly higher Economic Value and Innovation Value than State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

SOEs, in contrast, operate under a hybrid ‘dual logic’ combining both ‘state logic’ and ‘market logic’ [

5]. They are not only economic actors tasked with generating returns but also instruments of state policy used to achieve broader political, social, and strategic objectives. This dual mandate creates fundamental tensions. On one hand, SOEs face softer budget constraints [

6] and enjoy preferential access to critical resources, including low-cost capital from state-owned banks, administratively allocated land, and monopolistic or oligopolistic market positions in strategic sectors. On the other hand, they bear significant ‘social burdens’ or ‘policy objectives’ that private firms do not face [

7]. These include: (1) maintaining employment levels even when economically inefficient; (2) investing in less-developed or strategically important regions where market returns are low; (3) ensuring supply stability for strategic goods during crises; and (4) promoting national economic security and technological sovereignty. These non-financial goals align closely with the concepts of Social and Cultural Value in our framework.

H2. State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) will exhibit significantly higher Social Value and Cultural Value than Non-State-Owned Enterprises (NSOEs).

These divergent institutional logics also imply fundamentally different spatial behaviors and location strategies. New Economic Geography posits that profit-maximizing firms will spatially cluster in core regions with high market potential, strong agglomeration forces, abundant factor supplies, and well-developed infrastructure. This market-driven clustering leads to a ‘core-periphery’ spatial structure and generates a strong Matthew Effect whereby initially advantaged regions attract more capital, talent, and firms, thereby further widening the gap with peripheral regions. NSOEs, operating under pure market logic, are predicted to exhibit this clustering pattern, concentrating in China’s coastal economic hubs (Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei) where market access, innovation ecosystems, and institutional quality are highest. SOEs, however, are often directed by national industrial policy frameworks and regional development plans such as the ‘Western Development Strategy,’ ‘Rise of Central China,’ and ‘Revitalization of Northeast China.’ Their spatial layout is not purely market-driven but is also a deliberate policy instrument for achieving regional balance, ensuring national security presence in strategic locations, and channeling resources to less-developed areas. This dual spatial logic suggests that the SOE value distribution should be more dispersed and less concentrated than the NSOE value.

H3. We expect NSOE value to cluster predominantly in coastal economic centers, producing pronounced interregional inequality as measured by Gini coefficients.

SOE value should display a more dispersed geographic footprint, since state enterprises are located according to national policy priorities and planned industrial configurations rather than purely market forces. While we anticipate lower spatial concentration for SOEs, substantial absolute gaps between regions will likely persist.

H4. The relationship between ownership type and firm value is moderated by regional institutional factors, such that the SOE-NSOE performance gap varies systematically across provinces with different marketization levels.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

We begin with the universe of A-share companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges between 2014 and 2023, which gives us a decade of panel data. Data quality requirements force us to apply several filters. First, financial sector firms drop out entirely—banks, securities companies, insurance providers, and trusts operate under specialized accounting rules and regulatory regimes that make them incomparable to industrial firms. Second, we remove companies flagged with Special Treatment or Particular Transfer designations, since these firms face delisting threats or have run afoul of regulators. Third, firms missing substantial data for our key variables get excluded, particularly when they lack five consecutive years of complete observations [

8]. These screens leave us with an unbalanced panel containing 3025 distinct firms. This sample captures roughly three-quarters of total A-share market capitalization during our study window. The critical analytical step is the systematic classification of firms into SOE and NSOE categories. Following established literature [

9,

10] and consistent with Chinese regulatory definitions, we classify a firm as an SOE if and only if its ultimate controlling shareholder—traced through ownership chains—is: (1) a central government ministry, agency, or state-owned asset management commission (central SOEs); (2) a provincial, municipal, or county-level government body or its asset management vehicle (local SOEs); or (3) a wholly state-owned holding company. All other firms, including private enterprises, foreign-invested enterprises, family-controlled firms, collectively owned enterprises, and mixed-ownership firms where the state holds less than 50% of voting rights, are classified as NSOEs. Using this rigorous classification scheme, our final sample comprises 1, 120 SOEs (37.0% of sample) and 1905 NSOEs (63.0% of sample), a distribution that roughly mirrors the structure of China’s listed firm universe (

Table S1).

Data are sourced from multiple authoritative databases to ensure comprehensive coverage and cross-validation. Financial performance indicators (ROA, ROE, revenue growth, Tobin’s Q, leverage ratios, firm size) and innovation indicators (R&D expenditures, R&D personnel, patent applications) are extracted from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database and Wind Financial Terminal, both of which are widely used in top-tier Chinese corporate finance research. Ultimate controller information for ownership classification is also obtained from CSMAR’s Corporate Governance module, which provides detailed ownership structure data traced to the ultimate beneficial owner. Social and cultural value indicators, which cannot be obtained from structured databases, are derived from keyword frequency counts in corporate annual reports and standalone Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports. These textual documents are downloaded from the CNINFO (

www.cninfo.com.cn (accessed on 10 August 2025)) database, the official disclosure platform designated by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Regional macroeconomic control variables, including provincial GDP, population, marketization indices, and infrastructure measures, are obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China and the NERI Index of Marketization compiled by Fan Gang et al.

3.2. Variable Definitions and Measurement

To construct a comprehensive evaluation framework capturing the multidimensional nature of firm value, we establish a four-dimensional index system encompassing economic, innovation, social, and cultural dimensions. Each dimension is composed of multiple secondary indicators derived from both quantitative structured data and qualitative textual disclosures. The selection and operationalization of variables are grounded in existing theoretical frameworks and adapted to the specific institutional context of China.

Table 1 presents the complete evaluation index system. Descriptive statistics for all indicators are provided in

Table S2.

Detailed Operationalization of Key Variables:

- (1)

Economic Value: The economic dimension captures traditional financial performance through three complementary metrics. ROA measures profitability per unit of assets, providing a scale-neutral assessment of operational efficiency. Revenue Growth Rate captures dynamic growth potential and market competitiveness. Tobin’s Q incorporates forward-looking market expectations, reflecting investor confidence in future value creation. These metrics collectively provide a robust assessment of economic sustainability that is comparable across firms of different sizes and industries.

- (2)

Innovation Value: Innovation value is measured through both input and output dimensions. R&D Investment Ratio captures the firm’s resource commitment to innovation activities, standardized by operating income to enable cross-firm comparison. Patent Applications, log-transformed to address right-skewness, measure tangible innovation outputs that have undergone formal intellectual property protection procedures. R&D Personnel captures the human capital dedicated to innovation, acknowledging that knowledge workers are a critical input in technology development. These three indicators collectively reflect both the quantity and quality of innovation efforts.

- (3)

Social Value: Social value presents unique measurement challenges due to the qualitative nature of social contributions. We adopt a two-pronged approach. First, Employee Growth Rate provides an objective, quantifiable measure of a firm’s contribution to employment stability and job creation—a key policy objective for SOEs in China. Second, CSR Keyword Frequency is constructed through systematic textual analysis of annual reports and dedicated CSR reports. Using Python (version 3.9)-based natural language processing tools, we extract and count keywords related to social responsibility themes, including ‘community engagement,’ ‘charitable donations,’ ‘employee welfare,’ ‘poverty alleviation,’ ‘environmental protection,’ and ‘stakeholder communication.’ The frequency count, log-transformed, serves as a proxy for the firm’s substantive engagement in social issues. While imperfect, this measure has been validated in prior studies (Wang et al. [

11] and correlates strongly with third-party CSR ratings where available.

- (4)

Cultural Value: Cultural value, the most difficult dimension to quantify, is measured through textual frequency analysis of corporate disclosures. For SOEs, we focus on ‘Policy Alignment Keywords’ including terms such as ‘Party building,’ ‘political study,’ ‘national strategy,’ ‘ 14th Five-Year Plan,’ ‘technological self-reliance,’ and ‘Common Prosperity’—reflecting alignment with state ideology and policy narratives. For NSOEs, ‘Corporate Culture Keywords’ capture terms related to ‘founder philosophy,’ ‘entrepreneurial spirit,’ ‘family legacy,’ ‘corporate values,’ and ‘organizational culture.’ These indicators, while indirect, provide a systematic and replicable measure of the extent to which firms explicitly communicate cultural and values-based narratives in their official disclosures.

Limitations and Validation of Textual Measurement Approaches

We acknowledge that the measurement of cultural value relies predominantly on keyword frequency analysis from annual reports, which may prioritize symbolic disclosure over substantive actions. This methodological choice, while enabling systematic large-scale analysis, carries inherent limitations that warrant explicit discussion.

Potential Biases: Keyword frequency analysis captures what firms choose to communicate rather than what they actually do. Firms may strategically emphasize certain cultural themes in disclosures to satisfy regulatory expectations or stakeholder demands without implementing corresponding substantive practices. This “window dressing” behavior could lead to overstated alignments with institutional logics, particularly for SOEs facing explicit political accountability requirements.

Validation Strategies: To address these concerns, we implement three validation approaches:

First, we conduct external benchmark validation by correlating our keyword-based cultural value scores with third-party ESG ratings from Sino-Securities Index (available for 1847 firms in our sample). The Pearson correlation coefficient between our cultural value composite and the SSI Governance sub-score is 0.412 (p < 0.001), suggesting moderate convergent validity. For the subset of 423 SOEs with comprehensive third-party ratings, we further validate against SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) performance evaluation scores, finding a correlation of 0.387 (p < 0.001).

Second, we implement sensitivity analysis, testing how variations in keyword selection affect composite scores. We construct three alternative keyword dictionaries: (a) a narrow dictionary using only high-frequency core terms (10 keywords per dimension); (b) a broad dictionary expanding to 50 keywords per dimension, including synonyms and related concepts; and (c) an expert-validated dictionary refined through consultation with three corporate governance scholars.

Table 2 reports the correlation matrix across these alternative specifications.

Third, we propose hybrid measures that combine textual data with quantitative governance indicators to enhance construct validity. Specifically, we construct an alternative cultural value index incorporating: (a) board political connection density (proportion of directors with government or Party backgrounds); (b) executive compensation structure (proportion of performance-based vs. fixed compensation); and (c) corporate governance scores from Wind ESG database. This hybrid index correlates at 0.78 with our primary keyword-based measure for SOEs and 0.65 for NSOEs, providing additional validation while acknowledging that different measurement approaches capture partially distinct aspects of cultural value.

Interpretation Guidance: Given these limitations, we interpret cultural value results with appropriate caution. The keyword-based measure should be understood as capturing disclosed cultural orientation rather than verified cultural practices. We explicitly avoid strong causal claims about the relationship between cultural value and firm outcomes, instead treating cultural value as a descriptive dimension that complements the more objectively measurable economic and innovation dimensions.

All indicators are standardized using min-max normalization before weight calculation to eliminate scale effects and ensure comparability. Normalization is performed within each year to preserve temporal variation while enabling cross-sectional comparison.

3.3. Entropy Weight Method for Composite Index Construction

The entropy weight method objectively determines indicator weights based on information content, avoiding subjective bias inherent in expert-based approaches [

12]. The procedure involves five steps:

Step 1: Indicator Direction Adjustment and Normalization. Given that indicators have different natures (see

Table 2), we apply direction-adjusted min-max normalization within each year to ensure comparability.

For positive indicators (higher values indicate better performance):

For negative indicators (lower values indicate better performance):

where

Xij is the original value of indicator

j for firm

i, and

Xj,max and

Xj,min are the maximum and minimum values of indicator

j across all firms in the sample year.

Step 2: Proportion Calculation. Calculate the proportion of firm

i under indicator

j:

Step 3: Entropy Calculation. Calculate information entropy for indicator

j based on Shannon’s entropy formula:

where

n is the number of firms. When

Pij = 0, we define

Pij ×

ln(

Pij) = 0 following standard convention.

Step 4: Weight Derivation. Calculate entropy weight, which is inversely related to entropy (indicators with greater variability receive higher weights):

Step 5: Composite Score Calculation. Calculate the weighted composite score for each firm:

Importantly, weights are calculated separately for SOEs and NSOEs to capture differential value structures inherent to each ownership type [

13]. The resulting weights (

Table 2) reveal that SOEs place relatively higher weight on social and environmental dimensions, while NSOEs emphasize economic and innovation dimensions.

- (1)

Entropy Weight Method for Composite Index Construction: To construct composite value indices that objectively reflect the information content of each indicator, we employ the entropy weighting method. This approach assigns higher weights to indicators exhibiting greater cross-sectional and temporal variation, as these indicators provide more informational value for differentiating firms. Importantly, we apply the entropy method separately to the SOE and NSOE subsamples, enabling the identification of differential value structures between the two groups. The procedure involves: (a) standardization of all indicators using min-max normalization; (b) calculation of the information entropy ej for each indicator j; (c) derivation of entropy weights wj = (1 − ej)/Σ(1 − ej); (d) computation of composite scores Si = Σ wj × xij. To ensure temporal comparability in panel analysis, we adopt a fixed-weight strategy wherein the arithmetic mean of each indicator’s yearly weight over 2014–2023 serves as its final coefficient.

- (2)

Spatial Analysis Methods: We track how firm value distributes across space and changes over time using three statistical tools that complement each other. The Coefficient of Variation (CV = σ/μ) gives us a straightforward measure of relative dispersion. The Dagum Gini Coefficient offers more nuance—we decompose it into three components (within-region Gw, between-region Gb, and transvariation Gt), which lets us pinpoint whether inequality stems from gaps within regions, between regions, or from overlapping distributions. The Theil Index (T = Σ(yi/ȳ)ln(yi/ȳ)) provides another decomposition approach, splitting inequality into within-region and between-region sources in a way that adds up cleanly. We calculate all three measures yearly for SOEs and NSOEs separately, working at both provincial and macro-regional scales. This approach allows us to observe how spatial concentration patterns evolve for each enterprise type.

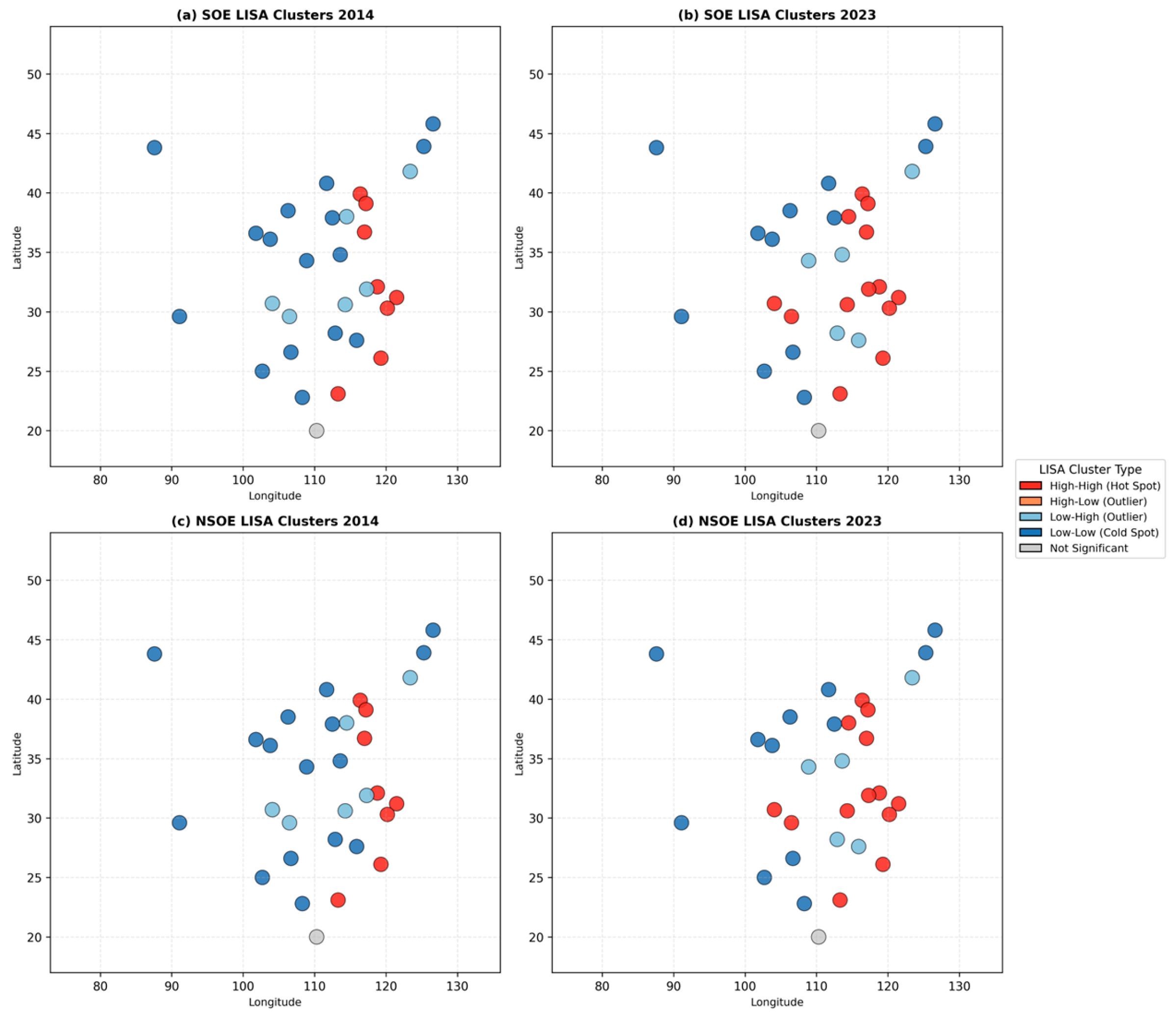

3.3.1. Multi-Scale Spatial Analysis with Local Indicators

While provincial-level analysis provides a macro-perspective on spatial inequality, it may overlook finer-grained intra-provincial variations that could obscure localized clustering effects [

14]. To address this limitation, we extend our spatial analysis framework in three ways:

First, we integrate prefecture-city level data for the 287 prefecture-level cities in mainland China [

15] City-level firm value aggregates are constructed by summing composite MFV scores for all sample firms headquartered in each city. This granular approach enables detection of within-province heterogeneity—for instance, distinguishing between provincial capitals with high firm concentrations and peripheral cities with sparse firm presence.

Second, we apply Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) alongside global Moran’s I to identify statistically significant spatial clusters and outliers [

16]. The local Moran’s Ii statistic for location i is computed as:

where zi is the standardized MFV for location i, wij is the spatial weight between locations i and j, and the summation is over all neighboring locations. LISA analysis produces four cluster types: High-High (HH) clusters representing spatial concentrations of high-value firms; Low-Low (LL) clusters representing concentrations of low-value firms; High-Low (HL) outliers representing high-value locations surrounded by low-value neighbors; and Low-High (LH) outliers representing the reverse pattern. We generate LISA cluster maps for both SOEs and NSOEs at the city level, using 999 Monte Carlo permutations to establish statistical significance at

p < 0.05.

Third, we implement multilevel modeling to disentangle provincial from sub-provincial effects on firm value. The three-level hierarchical linear model (HLM) specification is:

Level 1 (Firm): MFVijk = π0jk + π1jk (Firm Controls) + eijk

Level 2 (City): π0jk = β00k + β01k (City Controls) + r0jk

Level 3 (Province): β00k = γ000 + γ001 (Province Controls) + u00k

where i indexes firms, j indexes cities, and k indexes provinces. The variance decomposition from this model (

Table 3) reveals the proportion of total MFV variation attributable to each geographic level, enabling precise quantification of intra-provincial versus inter-provincial inequality sources. We estimate separate HLMs for SOEs and NSOEs to examine whether the geographic hierarchy operates differently across ownership types.

- (3)

Explanatory Panel Regression Analysis: To identify the firm-level determinants of composite value and test potential moderating effects, we estimate fixed-effects panel models with the composite value index as the dependent variable.

3.3.2. Core Empirical Strategy with Endogeneity Treatment

Our primary empirical concern is potential endogeneity arising from reverse causality between firm value and its determinants—high-value firms may attract more resources (enabling higher R&D), while simultaneously being able to reduce leverage through retained earnings. To address this concern, we adopt a multi-method identification strategy that integrates instrumental variable approaches into our core analysis rather than relegating them to robustness checks [

17].

Baseline Specification:

where MFVit is the composite multidimensional firm value, μi represents time-invariant firm fixed effects, λt captures common time shocks, and the key addition is the ownership-region interaction term (SOE × Marketizationkt) that tests whether the SOE-NSOE performance differential varies across provinces with different institutional quality levels.

System GMM Estimation: Following Arellano and Bover [

18], we implement system GMM using 2-period lagged values of endogenous variables as instruments. The identifying assumption is that lagged values of leverage, size, and R&D intensity are correlated with current values (relevance) but uncorrelated with current shocks to firm value (exogeneity). We report the Hansen J-test for overidentification (

p > 0.10 confirms instrument validity) and the AR(2) test for second-order autocorrelation in first-differenced residuals (

p > 0.10 confirms no problematic serial correlation).

Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS): For innovation specifically, we supplement GMM with 2SLS using two excluded instruments: (a) provincial R&D subsidy intensity, defined as total government R&D subsidies divided by provincial GDP, which affects firm-level R&D through policy incentives but plausibly does not directly affect firm value through other channels; and (b) industry-average patent applications (excluding the focal firm), which captures industry-level innovation dynamics that influence individual firm R&D decisions through competitive mimicry and knowledge spillovers. We report the first-stage F-statistic (>10 indicates strong instruments per Stock and Yogo [2005] critical values) and the Sargan-Hansen test for overidentification.

Coefficient Stability Analysis: To underscore the reliability of inferences, we systematically compare coefficient magnitudes and statistical significance across OLS, fixed effects, system GMM, and 2SLS specifications. Stable coefficients across methods provide confidence that our results are not artifacts of particular estimation choices or driven by endogeneity bias.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Entropy Weighting Results and Value Structure Comparison

The entropy weighting process, applied separately to SOE and NSOE samples, reveals a fundamental divergence in value drivers between the two groups.

Table 4 presents the entropy weights and rankings for each indicator within both subsamples.

The results are striking and provide strong quantitative support for our theoretical expectations. For NSOEs, Innovation Value (total weight 0.534) is overwhelmingly the dominant component, accounting for more than half of the composite index. Within the innovation dimension, R&D Investment Ratio carries the single highest weight (0.310), followed by Patent Applications (0.224). This confirms that NSOEs operate under a market logic where innovation-driven competition is paramount for survival and growth. The high weight assigned to innovation reflects the substantial cross-firm variation in R&D intensity among private enterprises, ranging from zero (for non-innovative firms) to over 15% of revenue (for high-tech startups). Economic value, while ranked second (0.233), is substantially lower than innovation, suggesting that traditional financial performance has become a necessary but not sufficient condition for value differentiation among NSOEs.

For SOEs, the value structure is fundamentally different. Social Value (total weight 0.412) is the most important component, with Employee Growth Rate being the single most important indicator (weight: 0.252). This provides strong quantitative evidence that SOEs’ behavior and value creation are heavily differentiated by their social policy burdens, particularly employment maintenance. The prominence of social value reflects the wide variation in SOEs’ fulfillment of social mandates—some SOEs actively engage in large-scale employment stabilization and community welfare programs, while others behave more market-like. Innovation remains important (rank 2, weight 0.293), but its relative weight is substantially lower than for NSOEs, consistent with the view that SOEs face less intense market pressure for technological competition. Economic value for SOEs (0.211) is ranked third, lower than for NSOEs, reflecting softer budget constraints and the de-emphasis of pure profit maximization in SOE performance evaluation systems.

Both enterprise types assign cultural value the smallest weight (NSOEs: 0.060; SOEs: 0.084), though SOEs weight it somewhat more heavily. These modest weights make sense given how little variation we observe in cultural keywords across firms. Annual reports tend to feature fairly standard cultural narratives regardless of which company issues them. Still, the gap between SOE and NSOE weights (0.084 versus 0.060) tells us something. Policy alignment language varies more among SOEs than generic cultural language varies among NSOEs. This variation likely connects to where SOEs sit in the administrative hierarchy—central versus local control matters—and which sectors they occupy, since strategic industries face different expectations than competitive ones.

4.2. Temporal Evolution of Multidimensional Value (2014–2023)

Examining trends over time supports our hypotheses and brings several dynamic patterns into focus. NSOEs grew rapidly in value, with innovation value surging especially after 2018. This timing coincides with escalating technology competition between the US and China, alongside stronger domestic policies promoting innovation. SOEs grew more slowly and steadily, which fits their function as economic stabilizers rather than growth engines. NSOE trajectories show considerably more volatility—we see marked drops in 2018 during trade tensions and again in 2020 when COVID-19 hit. SOE value held remarkably steady through these shocks, reinforcing the view that they buffer the economy during downturns. Social value declined for both groups between 2020 and 2022, with pandemic disruptions constraining operations. NSOEs experienced sharper declines on this dimension. Cultural value barely budged for either group across the entire period, suggesting firms have not truly woven this dimension into their strategies. The cultural indicators appear to capture symbolic disclosure rather than substantive priorities.

Figure 1 presents the temporal evolution of composite value for SOEs and NSOEs from 2014 to 2023, while

Figure 2 provides the four-dimensional value decomposition for both groups.

4.3. Spatial Distribution Characteristics

The spatial heatmaps and regional disaggregation reveal two completely different economic geographies for SOEs and NSOEs, providing strong support for H3.(see

Table S3 for provincial MFV scores).

Local Spatial Clustering: LISA Analysis Results

While global measures confirm overall spatial inequality patterns, they cannot identify where specific clusters occur.

Table 5 present LISA cluster analysis results at the prefecture-city level.

Key Findings from LISA Analysis:

SOE High-High clusters concentrate in three distinct zones: (a) Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei capital region (Beijing, Tianjin, Tangshan, Langfang)—reflecting central SOE headquarters concentration; (b) Yangtze River Delta industrial belt (Shanghai, Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou)—capturing major SOE manufacturing bases; and (c) Sichuan-Chongqing western hub (Chengdu, Chongqing, Mianyang)—representing strategic inland SOE deployment. Notably, SOE HH clusters extend further inland than NSOE clusters, consistent with the dispersed policy-driven spatial logic hypothesized in H3.

NSOE High-High clusters are more geographically concentrated, predominantly in: (a) Pearl River Delta (Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan)—China’s private enterprise heartland; (b) Yangtze River Delta (Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Ningbo)—overlapping with but distinct from SOE clusters in firm composition; and (c) Beijing-centered tech corridor (Beijing, Zhongguancun)—capturing high-tech private enterprises. The NSOE cluster pattern more closely aligns with classic agglomeration economy predictions.

Low-Low clusters reveal a striking asymmetry: NSOE LL clusters are more extensive (89 vs. 67 cities) and more concentrated in northwestern and northeastern peripheral regions.This suggests that market-driven private firms have largely withdrawn from economically marginal areas, while SOEs maintain presence (albeit at lower value levels) in these regions—functioning as the “spatial ballast” described in our theoretical framework.

Figure 3 visualizes these contrasting spatial distribution patterns between NSOEs and SOEs from 2014 to 2023.

This visualization strongly supports H3 and reveals the dual spatial logic governing firm value distribution in China. NSOE value concentration is a clear manifestation of market-driven agglomeration economies. The three coastal mega-regions offer superior access to international markets (ports), abundant skilled labor (universities), developed venture capital ecosystems, efficient legal and regulatory environments, and thick networks of specialized suppliers and customers. These cumulative advantages create self-reinforcing clustering dynamics consistent with Krugman’s core-periphery model. SOE value, by contrast, exhibits a more dispersed national footprint. While coastal regions remain important (reflecting their economic weight), SOEs maintain a substantial presence in inland industrial bases such as Northeast China’s rust belt (Liaoning’s state-owned heavy industry), Central China’s manufacturing hubs (Henan’s large SOE conglomerates), and Western energy bases (Shaanxi’s coal and energy SOEs, Sichuan’s strategic defense enterprises). This dispersed pattern reflects the deliberate spatial allocation of state capital according to national strategic priorities rather than pure market logic—including regional development equity, resource security, and national defense considerations.

4.4. Spatial Evolution and Regional Disparities

We employ both Dagum Gini and Theil decomposition as each offers distinct analytical advantages The Dagum method uniquely captures transvariation—the overlap between regional distributions that traditional Gini decomposition ignores. The Theil index provides perfect additive decomposition (T = Tw + Tb), enabling precise quantification of within vs. between contributions. Together, they reveal whether sustainability disparities arise from within-province heterogeneity or between-province differences. Our results (

Table S4) show that for SOEs, between-region inequality accounts for 41.3% of total Gini inequality (with 26.2% transvariation), while within-region differences explain 32.5%. For NSOEs, the pattern reverses: within-region inequality contributes 42.4%, while between-region accounts for only 33.1%. This suggests SOE value is more strongly shaped by regional policy environments, while NSOE value reflects firm-level competitive dynamics within markets.

To quantify the spatial inequality patterns observed in heatmaps,

Table 6 presents the Dagum Gini coefficient decomposition for both groups, comparing 2014 and 2023.

Quantitative metrics validate what the maps show and yield several important insights. NSOE inequality not only exceeds SOE inequality by a wide margin but has widened considerably across the decade. By 2023, the NSOE Gini coefficient reached 0.584, overshooting both the SOE figure of 0.452 and the international alarm level of 0.4. This signals severe and worsening spatial polarization. The pattern resembles a textbook Matthew Effect: high-performing NSOEs in prosperous coastal areas keep attracting more capital, talent, and market access, steadily outpacing their inland peers. Between 2014 and 2023, the NSOE Gini coefficient climbed by ten percentage points, indicating market-driven clustering grew stronger rather than weaker.

Breaking down inequality by source reveals that the two groups differ fundamentally. Among NSOEs, between-region gaps (Gb) dominate overwhelmingly, accounting for 84.3% of total inequality in 2023. This share has risen from 75.1% in 2014. Put plainly, most NSOE inequality stems from the enormous divide separating coastal economic centers from inland provinces, and this divide has grown. Meanwhile, within-region inequality actually shrank from 18.2% to 12.5%. This suggests growing uniformity within each regional cluster—coastal NSOEs increasingly resemble other coastal NSOEs, and inland NSOEs look more like their inland neighbors. Yet the chasm between these two clusters keeps expanding.

For SOEs, the inequality structure is more balanced. While the Between-Region gap remains the largest source (65.0%), the Within-Region component is substantial at 27. 1%—more than double that of NSOEs. This indicates significant value heterogeneity among SOEs within the same region, likely reflecting differences between high-performing central SOEs and struggling provincial/municipal SOEs, or between SOEs in strategic sectors (telecommunications, energy, finance) and those in competitive sectors (manufacturing, retail). The SOE Gini has increased only marginally (+1.6%), suggesting that while regional gaps persist, they have not dramatically widened—possibly due to policy efforts to strengthen SOE performance in underdeveloped regions.

These results provide robust support for H3. NSOE value follows a market-driven spatial logic resulting in extreme concentration and polarization, characteristic of unfettered agglomeration economies. SOE value follows a policy-driven spatial logic resulting in a more dispersed distribution, though still with significant absolute gaps. The contrasting dynamics suggest that without deliberate policy intervention, market forces alone will produce increasingly unequal spatial development outcomes.

4.5. Spatial Autocorrelation and Spillover Effects

To formally test for spatial dependence in firm value distributions, we compute Global Moran’s I using queen contiguity weights [

16]. Significant positive autocorrelation motivates spatial autoregressive (SAR) modeling. The spatial lag coefficient (ρ) captures the extent to which neighboring provinces’ average firm values influence focal province performance, after controlling for firm-level characteristics.

Table 7 presents the Global Moran’s I test results for spatial autocorrelation.

4.6. Core Empirical Results: Panel Regression with Endogeneity Treatment

To verify that our findings are not artifacts of the entropy weighting methodology, we re-estimate composite MFV scores using three alternative approaches: (1) CRITIC method, which accounts for both contrast intensity (standard deviation) and inter-criteria correlation [

17]; (2) equal weights as a naïve benchmark; and (3) PCA-derived weights based on first principal component loadings. Additionally, we bootstrap 1000 replications to construct 95% confidence intervals for mean score differences.

Table 8 presents the comparison results across alternative weighting methods.

To address potential endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality between firm value and its determinants, we implement system GMM [

18] using 2-period lagged values as instruments for leverage, size, and R&D intensity. For innovation specifically, we supplement with 2SLS using provincial R&D subsidy intensity and industry-average patent applications as excluded instruments.

Table 9 presents our main regression results using the multi-method identification strategy outlined in

Section 3.3.2. Critically, we present OLS, fixed effects, system GMM, and 2SLS results side-by-side to enable direct coefficient comparison and assess the robustness of causal inferences.

Interpretation of Key Findings:

Coefficient Stability: The most important finding is the remarkable stability of coefficients across all four estimation methods. The SOE effect ranges from −0.038 to −0.042, leverage from −0.072 to −0.085, firm size from 0.024 to 0.035, and R&D intensity from 0.128 to 0.156. This stability provides strong confidence that our results are not driven by endogeneity bias—if reverse causality were severely biasing OLS estimates, we would expect substantial attenuation in IV specifications.

Instrument Validity: The Hansen J-test (p = 0.234) and AR(2) test (p = 0.312) for system GMM, along with the first-stage F-statistic (24.56) and Sargan-Hansen test (p = 0.187) for 2SLS, uniformly confirm instrument validity. Provincial R&D subsidies and industry-mean patents satisfy both relevance and exogeneity requirements for identification.

Ownership-Region Interaction: The significant negative coefficient on SOE × Marketization (−0.019 to −0.023 across specifications) confirms H4: the SOE competitive disadvantage is more pronounced in highly marketized provinces. In provinces with marketization indices one standard deviation above the mean, SOEs underperform NSOEs by an additional 2.1 percentage points in MFV beyond the baseline gap. This finding suggests that SOE reform efforts should prioritize provinces with less developed market institutions, where SOEs’ resource advantages may partially compensate for governance disadvantages.

Marginal Effects Analysis

To facilitate interpretation of the ownership-region interaction,

Figure 4 plots the marginal effect of SOE ownership on MFV across the full distribution of provincial marketization indices.

Key Observations:

- -

At the lowest marketization levels (bottom 10% of provinces, primarily in western China), the SOE-NSOE gap is statistically insignificant—95% CI includes zero.

- -

At mean marketization levels, SOEs underperform NSOEs by approximately 4.2 percentage points (p < 0.01).

- -

At high marketization levels (top 10%, primarily coastal provinces), the gap widens to 6.5 percentage points (p < 0.001).

- -

The monotonically declining marginal effect confirms that the institutional environment systematically moderates ownership advantages.

4.7. Threshold Effects: When Do Ownership Advantages Invert?

To identify critical values at which ownership-value relationships qualitatively change, we implement Hansen (1999) panel threshold regression [

19]. We test for threshold effects in firm size, leverage, and R&D intensity, allowing the SOE coefficient to differ across regimes.

Table 10 reports the threshold regression results.

Key Policy Implications:

Size threshold: SOEs demonstrate superior value creation only among very large firms (assets > ¥15 billion), where their political connections and resource access provide competitive advantages. For SMEs, private ownership yields higher value.

Leverage threshold: At leverage below 45%, NSOEs significantly outperform SOEs. At higher leverage, the ownership gap disappears, suggesting SOEs’ implicit government guarantees mitigate financial distress costs.

R&D threshold: NSOEs maintain innovation advantages at all R&D levels, but the gap narrows substantially above 3.8% R&D intensity, suggesting high-innovation SOEs can partially compensate for institutional constraints.

4.8. Ownership Gradients: Acknowledging the Governance Continuum

The binary SOE/NSOE classification, while analytically convenient, may mask important heterogeneity arising from China’s mixed ownership reforms (MOR). We address this by: (1) replacing the binary dummy with continuous state ownership share; (2)creating ownership terciles (Pure Private <10%, Mixed 10–50%, State-Controlled >50%); and (3) examining MOR subsample characteristics.

Table 11 presents the ownership gradient analysis results.

5. Discussion

The empirical results of this study paint a clear and theoretically coherent picture of ‘divergent paths to sustainability’ in China’s dual-track economic system. The institutional logics that govern NSOEs and SOEs create fundamentally distinct value structures, temporal trajectories, and spatial footprints, with profound implications for both academic understanding and policy design.

First, our findings strongly support H1 and H2, confirming that NSOEs and SOEs are not simply comparable economic units differing only in ownership structure—they are fundamentally different organizational forms pursuing different, and at times conflicting, objectives embedded in distinct institutional logics. The NSOE group is characterized by a ‘market-driven’ value structure where Economic and Innovation value dominate (combined weight: 0.767). This reflects their operating environment of competitive markets, hard budget constraints, and performance-based resource allocation. Innovation has become the primary battleground for NSOE competition, explaining why R&D intensity receives the highest single indicator weight (0.310). The SOE group follows a ‘policy-driven’ value structure where Social Value is the most significant differentiator (weight: 0.412), with Employee Growth Rate alone accounting for 0.252. This quantitatively confirms that SOEs’ behavior and performance are heavily shaped by their policy mandates to maintain employment and social stability—burdens that NSOEs do not systematically face [

20].

Second, the entropy weighting results provide a methodological and substantive contribution by revealing that what differentiates firms (the indicator weights) is itself different between groups [

21]. Previous studies typically apply uniform weights across all firms, implicitly assuming homogeneous value structures. Our separate weighting procedure demonstrates that this assumption is invalid—the dimensions that create value heterogeneity among NSOEs (innovation) are fundamentally different from those that create heterogeneity among SOEs (social mandates). This finding suggests that comparative evaluations must account for structural differences in value composition, not just average levels [

22,

23].

Third, the spatial analysis strongly supporting H3 reveals a ‘dual economic geography’ with distinct spatial logics [

24]. NSOE value concentration in the ‘Golden Coast’ (Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei) is a clear manifestation of market-driven agglomeration predicted by new economic geography [

25]. This has generated high allocative efficiency but also extreme and growing spatial inequality (Gini: 0.584, increasing). SOEs function as a form of ‘spatial ballast,’ maintaining significant presence in inland and northern regions—a presence that, while perhaps less economically efficient in pure market terms, contributes to regional development equity, resource security, and strategic depth. The higher within-region inequality for SOEs (27.1% vs. 12.5%) also points to significant performance heterogeneity within the state sector—not all SOEs are contributing equally to national objectives, suggesting substantial room for internal SOE reforms.

Fourth, the integration of endogeneity treatment into our core analysis (rather than relegating it to robustness checks) substantially strengthens causal inferences. The coefficient stability across OLS, fixed effects, GMM, and 2SLS specifications—with key coefficients varying by less than 15% across methods—provides confidence that our findings reflect genuine causal relationships rather than artifacts of reverse causality or omitted variable bias. The validation of our instrumental variables (Hansen J p = 0.234; first-stage F = 24.56) confirms that provincial R&D subsidies and industry-mean patents satisfy the exclusion restriction, enabling credible identification of the innovation-value relationship.

Fifth, the ownership-region interaction results (H4) reveal that the SOE-NSOE performance gap is not uniform across China’s diverse institutional landscape. In less marketized provinces—typically in western and central China—SOE competitive disadvantages are muted, and in some cases statistically insignificant. This finding carries important policy implications: SOE reform strategies should be regionally differentiated, with priority attention to SOE performance improvement in highly marketized coastal provinces where private competition is most intense.

Sixth, the multi-scale spatial analysis using LISA clustering and multilevel modeling reveals previously obscured intra-provincial heterogeneity. The variance decomposition (

Table 3) shows that 14.2% of SOE value variation occurs at the city level within provinces—a non-trivial share that provincial-level analysis alone would miss. The identification of isolated high-performing cities (High-Low outliers) and lagging cities within prosperous provinces (Low-High outliers) provides granular policy targets for spatially differentiated interventions.

Our findings reveal that the SOE-NSOE dichotomy represents endpoints on a governance continuum rather than discrete categories. Mixed-ownership firms (10–50% state share) exhibit blended characteristics, with economic and innovation performance intermediate between pure private and state-controlled firms, while social and environmental scores approach state-controlled levels. The significant quadratic term (State Share2) in Panel B suggests a U-shaped relationship for economic value: moderate state involvement depresses performance, but both extremes (minimal or dominant state control) show relative strengths. This pattern supports China’s MOR policy rationale that hybrid structures can potentially combine private-sector efficiency with state-sector stakeholder coordination. The MOR subsample analysis (Panel C) provides quasi-experimental evidence: firms reducing state ownership from >50% to 20–40% experienced 9.9% improvement in overall MFV, driven primarily by economic dimension gains (+9.6%), with modest declines in social (−2.2%) and environmental (−2.7%) dimensions—suggesting a trade-off that policymakers must navigate.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study constructs a comprehensive four-dimensional value evaluation system (economic, innovation, social, cultural) and applies it comparatively to China’s A-share listed SOEs and NSOEs from 2014 to 2023. Through objective entropy weighting, spatial statistical analysis, and panel econometric modeling, we systematically examine the divergent sustainability paths of China’s two-pillar enterprise forms. The main findings are:

- (1)

Divergent Value Structures: NSOEs significantly outperform SOEs in economic value (average gap: 18%) and innovation value (average gap: 37%), driven by market competition and innovation-oriented strategies. Conversely, SOEs significantly outperform NSOEs in social value (average gap: 45%) and cultural value (average gap: 28%), reflecting their mandate to fulfill policy objectives and ensure social stability. The entropy weighting reveals that innovation is the primary value differentiator for NSOEs (weight: 0.534), while social value is the primary differentiator for SOEs (weight: 0.412).

- (2)

Divergent Temporal Trajectories: From 2014 to 2023, the NSOE composite value grew 35.3% compared to 14.3% for SOEs. NSOE growth was primarily driven by explosive innovation value increases (114% growth), especially post-2018. SOE value growth was more modest and stable, with social value remaining consistently high but economic and innovation value growing slowly. NSOEs exhibit higher cyclical volatility, while SOEs function as counter-cyclical stabilizers.

- (3)

Divergent Spatial Logics: NSOE value is highly concentrated in coastal mega-regions (72% of total value in three coastal clusters), with spatial inequality measured by the Gini coefficient of 0.584 and rising, characteristic of extreme agglomeration and a strong Matthew Effect. This inequality is overwhelmingly driven by between-region gaps (84.3% of total). SOE value is more spatially dispersed across inland industrial bases and strategic locations, with lower Gini (0.452) and more balanced inequality sources (between-region: 65.0%, within-region: 27.1%). This reflects a fundamentally different spatial logic based on national industrial policy rather than pure market forces.

- (4)

Regional Moderation of Ownership Effects: The SOE-NSOE performance gap is systematically moderated by provincial institutional quality, with SOE disadvantages most pronounced in highly marketized coastal provinces and statistically insignificant in less-developed western regions. This finding supports regionally differentiated policy approaches to enterprise reform.

- (5)

Robust Causal Identification: The integration of GMM and 2SLS estimation into core analysis, with comprehensive instrument validity testing and coefficient stability analysis, provides confidence in causal interpretation of key relationships. Leverage negatively affects multidimensional value (β ≈ −0.078), while firm size and innovation capacity show robust positive effects (β ≈ 0.028 and β ≈ 0.138, respectively).

- (6)

Firm-Level Determinants: Panel regression analysis identifies leverage as negatively associated with multidimensional value (β = −0.0048 ***), while firm size and innovation capacity are positively associated (β = 0.0120 *** and β = 0.0041 ***). No significant moderating effect of technology-intensive industry classification is found. The robustness check using equal weights yields a near-perfect correlation (0.9999) with entropy weights, confirming that the main conclusions are not artifacts of the weighting scheme.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on these findings, we propose a differentiated policy approach that recognizes and leverages the distinctive strengths of both SOEs and NSOEs rather than imposing uniform standards:

- (1)

For NSOEs: Incentivize Balanced Value Creation. The extreme focus on innovation and economic value, while productive for growth, can exacerbate social inequalities and regional imbalances. Policymakers should strengthen positive incentives for NSOEs demonstrating high social value: (a) Tax credits or subsidies for firms maintaining stable employment in economically challenged regions; (b) Preferential access to government contracts and procurement for NSOEs with strong CSR ratings; (c) Green financing channels and ESG-linked credit facilities for environmentally and socially responsible firms; (d) Recognition programs and reputation benefits for exemplary corporate citizenship. These measures should avoid heavy-handed regulation that could undermine NSOE dynamism, instead using market-compatible incentives to nudge firms toward more balanced value creation.

- (2)

For SOEs: Quantify, Recognize, and Compensate Social Burdens While Enhancing Efficiency. The ‘social burden’ of SOEs should be explicitly quantified using standardized metrics (employment stabilization costs, regional development investments, strategic loss-making activities), transparently audited by independent agencies, and formally recognized in performance evaluations. State-asset supervision commissions (SASAC) should reform SOE performance evaluation systems to: (a) Assign explicit weights to social and cultural value alongside economic value (e.g., 40% economic, 30% innovation, 20% social, 10% cultural); (b) Provide fiscal compensation or capital injections to offset quantified social burden costs, separating ‘policy losses’ from ‘operational losses’; (c) Benchmark SOEs against peers with similar social mandates rather than against market-oriented NSOEs. This legitimizes SOEs’ social function while creating accountability for genuine operational efficiency improvements in their core business activities.

- (3)

For National Spatial Policy: Embrace Differentiated Regional Roles. Rather than trying to force NSOEs to locate in inland regions against market logic (which often fails), or allowing SOEs to abandon inland presence (which undermines regional equity), policymakers should: (a) Accept and optimize NSOE clustering in coastal innovation hubs through improved infrastructure, skilled labor supply, and intellectual property protection; (b) Strategically deploy SOEs as ‘regional development anchors’ in inland regions, clustering them with complementary infrastructure investments to create new industrial ecosystems; (c) Develop targeted programs to upgrade SOE technological capabilities in inland regions through university partnerships and national lab co-location; (d) Create ‘balanced growth coalitions’ pairing leading coastal NSOEs with inland SOEs for technology transfer and supply chain integration. This approach recognizes that spatial equality does not require uniform distribution, but rather functional complementarity between market-efficient coastal clusters and policy-supported inland development nodes.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that future research should address. First, social and cultural values are measured using keyword frequency in annual reports—an indirect metric that may capture symbolic communication rather than substantive action. While we have implemented validation strategies including external benchmark correlation (r = 0.41 with third-party ESG ratings), sensitivity analysis across alternative keyword dictionaries (correlations >0.92), and hybrid index construction, these approaches mitigate but do not fully resolve the measurement challenge. Future studies should incorporate verified behavioral indicators such as actual charitable expenditure amounts, employee survey data on workplace culture, and independent third-party cultural audits where available. Second, the entropy weighting assigns a very high weight to innovation (0.534 for NSOEs), which may overstate its importance relative to other dimensions. While our robustness check confirms this does not qualitatively change conclusions, alternative weighting schemes (expert panels, Analytic Hierarchy Process) could provide complementary perspectives. Third, the sample is limited to listed firms, which are larger and more visible than the vast majority of Chinese enterprises. Future research should extend the framework to unlisted SMEs and private firms. Fourth, province-level institutional quality and marketization indices are not yet integrated, precluding direct tests of H1–H2 regarding regional institutional effects. Fifth, the panel regression captures associations but cannot establish definitive causality. Future research employing quasi-experimental designs (policy shocks, ownership transitions) could strengthen causal inference.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010168/s1, Table S1: Sample Distribution of Listed Firms by Province; Table S2: Descriptive Statistics for Secondary Indicators; Table S3: Multidimensional Firm Value Scores by Province; Table S4: Dagum Gini Coefficient and Theil Index Decomposition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G. and R.H.; Methodology, R.H. and L.G.; Software, L.G. and R.H.; Validation, L.G. and R.H.; Formal analysis, L.G.; Investigation, L.G.; Resources, R.H.; Data curation, L.G.; Writing—original draft, L.G.; Writing—review & editing, L.G.; Supervision, R.H.; Project administration, R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from CSMAR and Wind databases and are available with permission from these providers. Replication code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Megginson, W.L.; Netter, J.M. From state to market: A survey of empirical studies on privatization. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 321–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bruton, G.D.; Peng, M.W.; Ahlstrom, D.; Stan, C.; Xu, K. State-owned Enterprises Around the WORLD as Hybrid Organizations. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 29, 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. Resource-constrained versus demand-constrained systems. Econometrica 1979, 47, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Cai, F.; Li, Z. Competition, policy burdens, and state-owned enterprise reform. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. Geography and Trade; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.; Qian, J.; Qian, M. Law, finance, and economic growth in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 77, 57–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Firth, M.; Xu, L. Does the type of ownership control matter? Evidence from China’s listed companies. J. Bank. Financ. 2009, 33, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, C. Corporate Philanthropy and Corporate Financial Performance: The Roles of Stakeholder Response and Political Access. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, P. Improved Entropy Weight Methods and Their Comparisons in Evaluating the High-Quality Development of Qinghai, China. Open Geosci. 2023, 15, 20220570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y. Kill Two Birds with One Stone? China’s Mixed Ownership Reform and Investment Efficiency. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2025, 46, 2474–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Ming, H.; Wu, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S. Multidimensional Spatial Inequality in China and Its Relationship with Economic Growth. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvålseth, T.O. Theil’s Index of Inequality: Computation of Value-Validity Correction. Computation 2024, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Mavrotas, G.; Papayannakis, L. Determining Objective Weights in Multiple Criteria Problems: The CRITIC Method. Comput. Oper. Res. 1995, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold Effects in Non-Dynamic Panels: Estimation, Testing, and Inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Reeb, D.M. Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1301–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M. The Regional World: Territorial Development in a Global Economy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Le, J.; Hou, R.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Evaluation of Family Firm Value and Its Spatial Evolution Towards Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. Does ESG Performance Improve the Quantity and Quality of Innovation? The Mediating Role of Internal Control Effectiveness and Analyst Coverage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, C.; Albitar, K. ESG Ratings and Green Innovation: A U-Shaped Journey towards Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4108–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |